Abstract

Sterilizing high-carbon steel medical surgical blades is crucial for public health and safety. To enhance the sterilization efficiency of medical surgical blades, we used the Monte Carlo simulation method to study the effects of gamma irradiation sterilization parameters on high-carbon steel samples. Results show that the time required for irradiation sterilization can be decreased to 23.14 min or even 6.20 min, significantly shorter than the several hours required for chemical sterilization, by optimizing the irradiation facility parameters. The gamma source is a 1 cm thick 60Co, while the reflector is 20 cm thick cylindrical graphite. The five layers of high-carbon steel samples, each 1 cm thick, have areas of 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2 from top to bottom. The high-carbon steel sample is positioned 30 cm from the radiation source, resulting in energy deposited in the middle layer II zone of 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV/g, which is used for calculating the total sterilization time. This study provides a viable approach to improving the sterilization efficiency of disposable medical surgical blades and serves as a reference for further promoting irradiation sterilization technology in medical instruments.

Keywords: Monte Carlo simulation, Gamma irradiation sterilization, Medical surgical blade, Reflector

Subject terms: Bacteria, Fungi, Policy and public health in microbiology, Infectious diseases, Nuclear energy, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Medical surgical blades, widely used in hospitals, are primarily made from high-carbon steel, stainless steel, and other metals1. Typically, these blades measure about 5 cm in length and 1 cm in width2. Statistics show that, driven by population aging and rising chronic disease prevalence, the global annual market size for medical surgical blades exceeded 200 million USD in 20233. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is expected to surpass 5%3 from 2024 to 2030. To ensure patient safety, proper sterilization of surgical blades is essential4. Standard methods include sterilization of high-temperature, chemical, and irradiation5,6. Chemical sterilization often utilizes chlorine-based disinfectants, ethylene oxide, ozone, and ortho-phthalaldehyde. However, some agents can leave harmful residues on medical devices7. High-temperature methods, such as dry heat and high-pressure steam sterilization, may result in high energy consumption, extended processing times, and material deformation.

In response to these challenges, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has endorsed irradiation sterilization as an effective alternative8, updating its consensus standard database to promote radiation technology in medical devices9. Irradiation sterilization works by exposing microorganisms to high-energy rays (gamma rays, X-rays, or electron beams), causing ionization and resulting in sterilization10,11. This method offers several advantages over high-temperature and chemical sterilization, including continuous operation of the radiation source, enhanced processing efficiency, and the absence of toxic residues. Irradiation sterilization has seen significant application in various industries, including food12, pharmaceuticals, and health products, and has proven crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following studies that established its efficacy against the novel coronavirus13,14, irradiation technology was employed for disinfecting medical masks15 and protective clothing16, with numerous tests confirming its effectiveness. Historically, researchers have proposed using irradiation for sterilizing medical instruments, including surgical blades. Studies indicate that doses between 35 kGy and 50 kGy effectively sterilize blades without compromising their performance17. Gamma rays from sources like cobalt-60 (60Co)18 and cesium-137 (137Cs)19 are particularly effective due to their strong penetration capabilities.

In this study, we use the Monte Carlo method to develop a model consisting of a radiation source, irradiated sample, reflector layer, and shielding layer to simulate the gamma-ray sterilization process for medical surgical blades. The model evaluates how different parameters, such as the radiation source’s energy and thickness, the reflector’s material, size, and shape, the dimensions of the irradiated sample, and the distance from the radiation source to the irradiated sample (source-to-sample distance), collectively influence the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the irradiated sample. Based on these analyses, we determined the optimal parameters for the gamma irradiation device and calculated the time required to achieve a lethal dose for microorganisms under these conditions. This study presents a promising and practical method for improving the sterilization efficiency of disposable medical surgical blades while providing valuable insights for the broader application of irradiation sterilization technology in medical device sterilization.

Methods and materials

Gamma irradiation sterilization principle

The principle of gamma irradiation sterilization lies in the interaction between the gamma photons emitted by the radiation source and the atoms of microorganisms. Through mechanisms such as Compton scattering, the photoelectric effect, and the electron pair effect, the energy from the photons is deposited into the atoms of microorganisms. This deposition leads to microbial atoms’ direct or indirect ionization, resulting in physical and biological impacts that achieve sterilization. This process works in two primary ways: first, the nuclear radiation directly damages the chromosomes of bacteria, effectively killing them. Second, when radiation interacts with bacterial atoms and molecules, especially water, it generates free radicals. These free radicals can then damage the cells indirectly, causing further sterilization10.

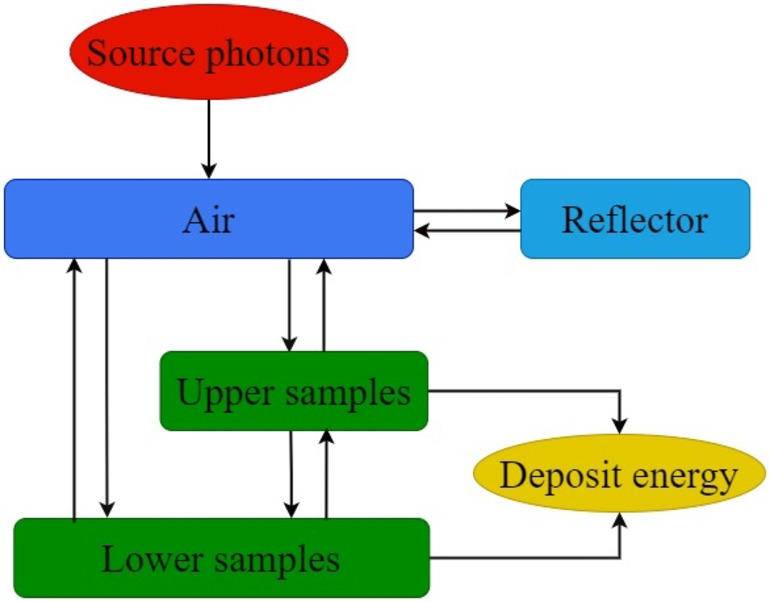

Due to the isotropy of gamma rays emitted by the radiation source, not all gamma rays interact with the sample, which can lead to a low utilization rate of the radiation. However, suppose a reflector encloses the radiation source and the irradiated sample. In that case, some gamma photons that do not directly hit the sample can still interact with it after scattering off the reflector. This occurs because the atoms in the reflector cause photon scattering. After interacting with the reflector, some scattered photons may return to the sample, increasing the number of photons interacting with the sample. As a result, the total energy deposited by gamma photons in the irradiated sample is greater than it would be without the reflector. This increase in energy deposition shortens the disinfection and sterilization time, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the irradiation sterilization process. Figure 1 demonstrates the photon motion process within the reflector, illustrating how scattered photons contribute to improved photon-sample interaction. This reflective technique could be applied in practical irradiation systems to optimize sterilization processes, enhancing energy efficiency and reducing operational time20,21.

Fig. 1.

The action process of gamma photons in an irradiation device containing a reflector.

Introduction to Monte Carlo simulation method

The Monte Carlo simulation method is a numerical technique that relies on random sampling to model complex systems, and its radiation transport uses the random walk of radiation particles within a given geometric structure. It is a well-established and effective method for solving radiation transport problems and analyzing particle energy deposition21,22. The Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in the United States developed the widely used Monte Carlo N-Particle (MCNP) code, which can simulate the transport of neutrons, photons (gamma rays, X-rays), electrons, or even coupled transport systems23. This MCNP program is employed in various fields, including dosimetry24, radiation protection and shielding25,26, radiology27, and more28.

In this study, we utilize the F6 output card in the MCNP program to calculate the energy deposited in the irradiated sample layers. This card allows for precise determination of the energy absorbed by each layer of the sample during gamma irradiation, contributing to the accurate modeling of the sterilization process. The following formula is applied to calculate the energy deposited in the high-carbon steel sample:

|

1 |

In Eq. (1), d represents the energy deposited by a single photon (MeV/g);  represents the atomic density (atoms/barn); m represents the mass of the cell element (g); H(E) represents the heating number (MeV/collision);

represents the atomic density (atoms/barn); m represents the mass of the cell element (g); H(E) represents the heating number (MeV/collision);  corresponds the microscopic total cross section (barns);

corresponds the microscopic total cross section (barns);  represents angular flux:

represents angular flux:

|

2 |

In Eq. (2), n represents the particle density (particles/cm3/MeV/stellar); v represents the speed (cm/sh) where 1 sh equals 10− 8 s. It should be noted that the energy deposition calculated using MCNP software is normalized, which is the average energy deposited by individual particles interacting with matter. Therefore, the total energy deposited by particle beams interacting with matter is calculated as follows:

|

3 |

In Eq. (3), DT is the total energy deposited by the particle beams interacting with matter, and N is the number of particles interacting with matter in the particle beam.

The primary dataset for MCNP in this study, derived from the ENDF/B-VI.8 evaluated data library, includes photon-material and electron-material interaction cross-section data sourced from MCPLIB04 (id plib=’04p’)29 and el03 (id elib=’03e’)30, respectively.

Materials and parameter settings

If we set the irradiated sample as surgical blades mixed with microorganisms, the model would become more complex and increase computational time. To simplify, we employed the MCNP program to simulate the energy deposition of a single 1.25 MeV gamma photon across a five-layer sample, as illustrated in Fig. 2(a). The left side of the sample consisted of high-carbon steel, while the right side modeled microorganisms composed of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. The layers were numbered 1 to 5, from top to bottom. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the energy deposited by the gamma photon was higher in the microbial layers than in the corresponding high-carbon steel layers, suggesting that when the steel reaches the sterilization dose, the microorganisms will also be effectively sterilized.

Fig. 2.

Simplification of irradiated samples. (a) Schematic diagram of high carbon steel and microorganism samples and (b) energy deposition of a single 1.25 MeV gamma photon in the sample.

Therefore, we simplified the sample to the material of the surgical blade, which is high-carbon steel. We used industrial gamma radiation sources, ¹³⁷Cs and ⁶⁰Co, with reflector materials such as graphite, polyethylene, water, concrete, aluminum, and iron. The sample rested on a stainless steel platform, and a cubic concrete shielding layer was modeled around the reflector to ensure safety31, as commonly designed in industrial irradiation facilities. Table 1 lists the material densities used in the model, which is critical for accurately simulating gamma radiation interactions. Figure 3 illustrates the experimental setup, where 101 represents the radiation source, 102 is the platform, 103 is the high-carbon steel sample, 104 and 106 are air spaces, 105 is the reflector, and 107 denotes the concrete shielding wall. The high-carbon steel sample (103) consists of five layers, numbered 1031 to 1035, representing stacked surgical blades with uniform thicknesses of 1 cm per layer. These layers, aligned along the same vertical axis, are named the top layer, upper middle layer, middle layer, lower middle layer, and bottom layer, respectively. Four sets of high-carbon steel samples, each consisting of five layers, were prepared. The dimensions of each set are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The density of materials in the irradiation model.

| Materials | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|

| High carbon steel | 7.820 |

| Aluminum | 2.699 |

| Iron | 7.874 |

| Polyethylene | 0.930 |

| Concrete | 2.300 |

| Graphite | 1.700 |

| Water | 1.000 |

| Stainless steel | 7.920 |

| Cesium | 1.870 |

| Cobalt | 8.900 |

Fig. 3.

Radiation sterilization device model.

Table 2.

Dimensions of high-carbon steel irradiated sample layers.

| Group | Edge length increment (cm) | The area of each layer of high carbon steel irradiation sample (cm2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top layer | Upper middle layer | Middle layer | Lower middle layer | Bottom layer | ||

| A | 10 | 10 × 10 | 20 × 20 | 30 × 30 | 40 × 40 | 50 × 50 |

| B | 20 | 10 × 10 | 30 × 30 | 50 × 50 | 70 × 70 | 90 × 90 |

| C | 30 | 10 × 10 | 40 × 40 | 70 × 70 | 100 × 100 | 130 × 130 |

| D | 40 | 10 × 10 | 50 × 50 | 90 × 90 | 130 × 130 | 170 × 170 |

We define the inner space of the concrete building as a cube with a side length of 400 cm. The concrete wall thickness is 50 cm to minimize gamma ray penetration. For the radiation sources, we use ¹³⁷Cs, which emits gamma photons with an energy of 0.662 MeV, and ⁶⁰Co, which emits gamma photons with energies of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV, each with a 50% probability. The radiation source shape is modeled as a square plate with 1 cm and 2 cm thicknesses, reflecting the commonly used single plate source32 and double plate source33 configurations in industrial irradiation. The reflector geometries are cubic and cylindrical shells, with internal dimensions of 300 cm × 300 cm × 300 cm for the cubic shell and Ф300 cm × 300 cm for the cylindrical shell. The reflector materials include aluminum, iron, polyethylene, concrete, water, and graphite, with thicknesses set at specific intervals: 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and continuing up to 35 cm. The source-to-sample distances were set at 30 cm, 50 cm, 70 cm, and 90 cm.

Results and discussion

To identify the factors influencing the energy deposited by a single photon in the high-carbon steel irradiated sample and to optimize the irradiation device parameters for improving the sterilization efficiency of medical surgical blades, we employed the MCNP software using the Monte Carlo simulation method. Through this approach, we established a model for irradiating medical surgical blades and simulated various relevant parameters. The results indicate that the factors affecting gamma photon energy deposited in the high-carbon steel irradiated sample include the energy of the gamma photons emitted by the radiation source, the thickness of the radiation source, the material and thickness of the reflector, the shape of the reflector, the source-to-sample distance, and the size of the high-carbon steel sample. Since the gamma photons emitted by the radiation source predominantly penetrate the high-carbon steel sample from the top down, the energy deposited by a single photon in the lower sample layers is less than that in the upper layers. We use the energy deposited in the bottom layer as the vital research index to ensure the complete sterilization of the high-carbon steel sample by gamma rays. We set the number of particle histories in each simulation to 109 to ensure that the error in each result does not exceed 0.001.

The effect of the radiation source on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

The effect of source photon energy on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

Figure 4 illustrates the scenario where the reflector is a cubic shell, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, the sample size corresponds to group A and the thickness of the radiation source is set to 2 cm. The radiation sources used are 60Co, emitting one gamma photon of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV per decay, and 137Cs, emitting one gamma photon of 0.662 MeV per decay. The reflector materials are aluminum, iron, polyethylene, concrete, graphite, and water.

Fig. 4.

Energy deposited by a single photon of different energies in the bottom layer of high-carbon steel sample with reflector materials of (a) aluminum, (b) iron, (c) polyethylene, (d) concrete, (e) graphite, and (f) water.

The findings suggest that the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the irradiated sample varies depending on the reflector’s thickness. It is evident that as the reflector thickness increases to a certain point, the energy deposited in the bottom layer stabilizes and no longer changes. Additionally, gamma photons with energies of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV (i.e., those produced by the decay of 60Co) deposit more energy in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample than the photons from 137Cs.

This result occurs because most photons generated by the radiation source interact directly with the high-carbon steel sample once they pass through the air. Photons with higher energy retain more energy after interacting with the air, meaning that the photons that reach the sample layer have tremendous energy, allowing them to deposit more energy into the sample. Another portion of the photons does not interact directly with the sample but instead interacts with the reflector, where they are scattered. Some of these scattered photons are reflected toward the high-carbon steel sample. The higher-energy source photons retain more energy after traversing the same air and interacting with the reflector, thereby deposing more energy into the high-carbon steel sample.

Based on this, we use 60Co as the radiation source in the subsequent stages of the study due to its higher energy deposition efficiency.

The effect of the thickness of the radiation source on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

Figure 5 presents the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample when the reflector is a cylindrical shell made of graphite, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, and the size of the irradiated sample is group A. The radiation source used is 60Co, with gamma radiation source thicknesses of 1 cm and 2 cm, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom sample layer using radiation sources of different thicknesses.

The results show that when the radiation source area is the same, the single photon released from the thinner source deposits more energy in the bottom sample layer. Two factors can explain this outcome. First, photons released from the radiation source interact with the atoms of the source material itself, causing them to lose energy. Consequently, the average energy of the gamma photons emitted from a thicker radiation source is lower when they reach the high-carbon steel sample, leading to reduced energy deposition. Second, photons emitted upwards from the source interact with the reflector and then pass through the radiation source again before reaching the high-carbon steel sample. A thicker radiation source causes the reflected photons to lose more energy before interacting with the sample. Thus, in practical applications, when the type and activity of the radiation source are the same, a radiation source with a smaller thickness should be chosen, as this effectively results in a higher energy deposition, improving the sterilization process, also referred to as a single-grid source or a grid source composed of finer source pencils.

The effect of the reflector on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

The effect of the reflector material and thickness on energy deposited by a single photon

Figure 6 (a) shows the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample when the reflector is in the shape of a cylindrical shell. In this setup, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, the sample size is group A, the radiation source is a 60Co source with a thickness of 1 cm, and the reflector materials are aluminum, iron, polyethylene, concrete, graphite, and water. The results indicate that as the thickness of the reflector increases, the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample also gradually increases, eventually reaching a stable value. At this point, the energy deposition ranks from highest to lowest: graphite, polyethylene, water, concrete, aluminum, and iron. The thickness required for stabilization varies for each material, with the values being 20 cm for graphite, 30 cm for polyethylene, 28 cm for water, 15 cm for concrete, 15 cm for aluminum, and 5 cm for iron. These findings align with those reported in the studies by Arvind D. Sabharwal34 and Ying-Hong Zuo35.

Fig. 6.

Energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer using reflectors of (a) different materials and (b) different shapes.

These results arise from the fact that when gamma photons with energies of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV are released from the radiation source, a portion of these photons interact directly with the high-carbon steel sample and deposits energy after traversing the air. Additionally, a small fraction of these photons undergoes scattering in the high-carbon steel sample, either continuing to penetrate or exiting the sample layer. After passing through the air, another portion of the photons first interacts with the reflector, producing a photoelectric effect or Compton scattering. Some of these scattered photons then interact with the high-carbon steel sample, depositing energy through the photoelectric effect or further scattering within the sample layer before continuing to penetrate or exit. When gamma photons interact with a reflector made of materials with low atomic numbers, such as graphite, polyethylene, and water, Compton scattering is more likely to occur. This results in more photons interacting with the high-carbon steel sample after being scattered by the reflector, increasing the total energy deposited in the high-carbon steel sample. Once the reflector reaches a specific thickness, photons can no longer penetrate it, and the count of scattered photons interacting with the sample stabilizes, as does the total energy deposited.

Specifically, polyethylene, with its small atomic number and low density (0.93 g/cm³), is less likely to interact with gamma photons. As a result, the thickness of the polyethylene reflector must be twice that of aluminum to achieve the same stable energy deposition per photon. In contrast, when gamma photons interact with high atomic number materials like iron, the probability of Compton scattering decreases, and the photoelectric effect dominates. In this process, the gamma photons transfer their energy to the iron atoms, ejecting photoelectrons. These photoelectrons gradually lose energy through interactions with the iron reflector or the surrounding air, eventually being absorbed. Graphite has a relatively low atomic number, which primarily causes gamma photons interacting with it to undergo Compton scattering. However, its high density increases the likelihood of interactions with photons, allowing it to increase the number of scattered photons interacting with the high-carbon steel sample while maintaining a smaller stable thickness than polyethylene.

It is evident that when the reflector reaches a certain thickness, graphite produces the maximum energy deposition. Therefore, graphite is selected as the reflector material for subsequent studies.

The effect of the reflector shape on the energy deposited by a single photon

Figure 6 (b) illustrates the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample, with a 90 cm source-to-sample distance, using a group B irradiated sample. The radiation source is a 60Co source with a thickness of 1 cm, and the reflector is either a cubic shell or a cylindrical graphite shell. The results show that when the reflector takes a cylindrical shape, the energy deposited by a single photon in the irradiated sample’s bottom layer is higher than that of a cubic shell.

This phenomenon can be attributed to the geometric characteristics of the cylindrical shell-shaped reflector. First, photons that do not directly interact with the high-carbon steel sample have a shorter average path in the air due to the cylindrical shape, resulting in reduced energy loss. Additionally, the curvature of the cylindrical shell inherently focuses the reflected photons toward the center, increasing the number of photons that interact with the high-carbon steel sample through reflection. As a result, the photons reflected in the sample possess higher energy upon interaction, leading to greater energy deposition. On the other hand, since the cylindrical shell has a smaller volume than the cubic shell, it requires less graphite (approximately 4.5 tons). Therefore, depending on the graphite purity used, choosing the cylindrical shell reflector can save between $10,000 and $50,00036,37.

Therefore, from the standpoint of maximizing energy deposited in the underlying sample layer and optimizing material usage cost-effectively, the cylindrical shell-shaped reflector is the most advantageous option.

The effect of the distance from the radiation source to the high-carbon steel irradiated sample on energy deposited by a single photon

According to the optimization measures discussed above, the shape of the reflector is set as a cylindrical shell, the material is specified as graphite, and the radiation source is chosen as 60Co with a thickness of 1 cm. The source-to-sample distances vary between 30 cm, 50 cm, 70 cm, and 90 cm. As illustrated in Fig. 7(a), the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the sample decreases as the source-to-sample distance increases. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors. First, the greater the source-to-sample distance, the longer the photon must travel through the air before interacting with the high-carbon steel sample, which reduces the photon’s energy. Second, most energy contribution comes from photons that reach the sample layer. As the source-to-sample distance increases, the solid angle between them decreases, allowing fewer photons to reach the sample directly, ultimately reducing the total energy deposited in the high-carbon steel sample.

Fig. 7.

(a) Energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of high-carbon steel samples at varying distances from the radiation source. (b) Zoning diagram. (c) Energy deposited by a single photon in each region of high-carbon steel sample under different source-to-sample distances with the DUR.

In practical irradiation sterilization, it is essential to consider the sterilization dose and the dose uniformity ratio (DUR), which is the ratio of the maximum to minimum absorbed dose within the irradiated product38. To investigate the effect of distance on the DUR, each layer of the high-carbon steel samples was divided into five zones along the horizontal direction. These zones, numbered I to V from the inner to the outer regions, are defined based on their dimensions as illustrated in the Fig. 7(b). The calculated energy deposited by a single photon within each zone of group A high-carbon steel samples at different source-to-sample distances is shown in the Fig. 7(c).

The results reveal that merely increasing the source-to-sample distance is insufficient to reduce the DUR to the commonly used value of 1.6 in irradiation practices39. In fact, prior studies have demonstrated that gamma irradiation up to 50 kGy does not compromise the integrity of surgical blades, where a DUR of 2 is acceptable. To address the high DUR from the surgical blades’ density, a secondary irradiation method can be used40. We set a DUR below the maximum allowable value, such as 1.6. The sterilization time for a single irradiation cycle is calculated based on the energy deposited by a single photon in the sample. After the first irradiation, surgical blades in the high-dose regions, which have reached the sterilization dose, are removed from the irradiation position. Meanwhile, blades in the low-dose regions, which have not yet reached the sterilization dose, either remain in place or are repositioned within the low-dose areas, depending on the relative dose levels. After placing unsterilized blades in the high-dose regions, they undergo the next round of irradiation.

Taking the A group source sample at a distance of 30 cm as an example, assuming a DUR setting of 1.6, the minimum energy deposition required from a single photon in high-carbon steel for the first irradiation round is 8.0725 × 10− 7 MeV/g. After one irradiation, the top layer, upper middle layer, middle layer II and III zones, lower middle layer III and IV zones, and bottom layer V zone can be removed from the irradiation device. However, the middle layer I zone, lower-middle layers I and II zones, and bottom layers I, II, III, and IV zones require a second irradiation. Since the energy deposited a single photon in the middle layer I and bottom layer I zones differs significantly, the surgical blades in these two zones can be swapped before the second irradiation. Similarly, the surgical blades in the bottom layer IV zone can be swapped with those in the bottom layers II and III zones, ensuring more uniform irradiation.

Thus, the method of zonal dual-round irradiation effectively mitigates the DUR constraints imposed by the source-to-sample distance. To maximize photon energy deposition in high-carbon steel samples, a source-to-sample distance of 30 cm was selected.

The effect of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample size on energy deposited by a single photon

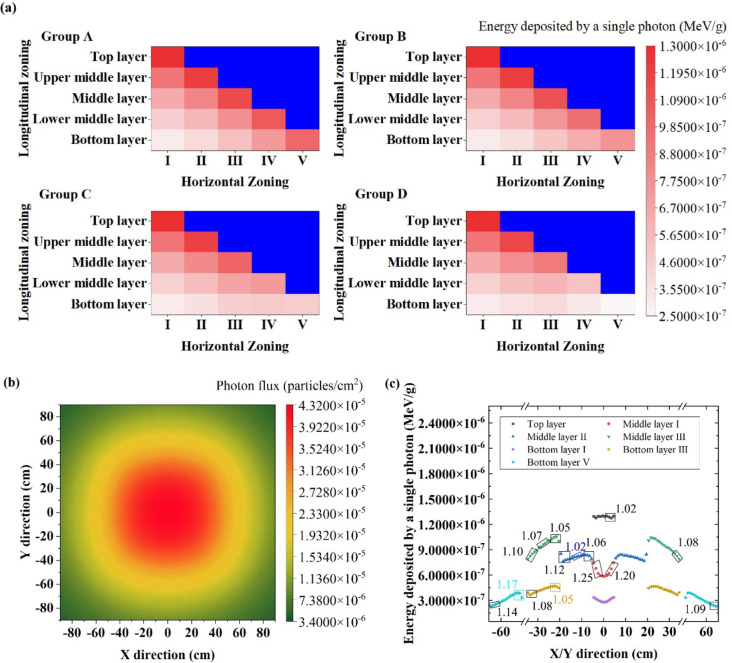

When the reflector is configured as a cylindrical graphite shell, the radiation source is set as 60Co with a thickness of 1 cm, and the source-to-sample distance is fixed at 30 cm, the energy deposited by a single photon in different regions for four groups of samples (with dimensions listed in Table 2) is illustrated in Fig. 8(a). It can be observed that the energy deposited by a single photon in zone V of the bottom layer decreases significantly as the sample size increases.

Fig. 8.

(a) The energy deposited by single photon in different regions of high-carbon steel samples of different sizes when the source-to-sample distance is 30 cm. (b) The photon flux at a distance of 30 cm below the radiation source. (c) The energy deposited by a single photon in each sampling cube.

This phenomenon is because as the size of the high-carbon steel sample increases, the photons interacting with the sample have more opportunities to interact with it, thus transferring more total energy to the sample. However, the simulation, which uses a volume source composed of multiple isotropic point sources, shows the photon flux 30 cm below the radiation source, as depicted in Fig. 8(b). As Fig. 8(b) demonstrates, the number of photons traveling in the horizontal direction decreases as the distance from the vertical axis within the irradiation device’s reflector increases. This observation is consistent with earlier findings by Diming Z32. Consequently, when the bottom sample layer becomes too large, although the number of photon interactions with the high-carbon steel sample increases, the peripheral regions of the sample interact less with the photons compared to areas near the vertical axis. As a result, the deposited energy in the peripheral regions is lower. When normalized, it shows that the energy deposited by a single photon decreases as the sample size increases beyond a certain point.

This highlights that simply increasing or reducing the size of the high-carbon steel sample is not a practical approach for optimizing irradiation. The characteristics of the radiation source must be considered to determine the appropriate sample size for effective irradiation. Since the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer V of the group D high-carbon steel sample is too low, we chose the group C as the subject for further sterilization time calculations. This ensures effective sterilization and uniform irradiation while maximizing the processing capacity per cycle. A DUR of 1.6 was roughly set, with the single irradiation time determined by the energy deposited by a single photon in the middle layer II. To evaluate the uniformity of blades with different lengths after a single irradiation, 150 cubes with a side length of 1 cm were sampled diagonally across various regions, including 10 from the top layer, 70 from the middle layer, 10 from bottom layer I, and 30 each from bottom layers III and V. For surgical blades with dimensions of 3 cm and 4 cm, the DUR was calculated using continuous sets of 3 and 4 cubes, as shown in Fig. 8(c). The energy deposited by a single photon in each small cube within the same region varies. For instance, in the middle layer II region, starting from the cubes near layer I, the energy deposited by a single photon initially increases, then gradually decreases, but reaches its maximum in the cubes near layer III. This variation arises from the interplay between the photon flux distribution in the horizontal plane and the stacking effect of high-carbon steel layers. The 4 cm surgical blades exhibited greater dose non-uniformity than the 3 cm blades in certain regions, such as the outer edge of the bottom layer V, due to their larger spatial coverage. Within the evaluated regions, the DUR for the 4 cm blades peaked at 1.25 when placed at the edge of middle layer I, and reached its minimum of 1.02 when placed in middle layer II or the top layer. These results highlight the importance of selecting the placement area based on blade size. For secondary irradiations, in addition to repositioning the blades, horizontal rotation is recommended to improve dose uniformity.

In the group C, the minimum energy deposited by a photon in middle layer II was 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV/g, while the maximum energy deposited in the top layer was 1.3030 × 10− 6 MeV/g, resulting in a DUR of 1.70, which is below the allowable maximum of 2. Accordingly, 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV/g was used to calculate the single irradiation time.

Estimation of the shortest radiation sterilization time

Using the parameters from the optimized irradiation device model, with a 20 cm thick graphite cylindrical shell reflector and a source-to-sample distance of 30 cm, C group high-carbon steel samples were selected (with layer sizes of 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2). The minimum energy deposition of 7.6493 × 10⁻⁷ MeV/g in the middle layer II was used to calculate the irradiation time for a single exposure. At this point, the sample’s DUR is 1.7, which is below the maximum allowable value of 2.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)41 and the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (formerly the Ministry of Health)42 recommend a standard sterilization dose of 25 kGy to ensure a high level of sterility, especially in cases where the contamination level or the type of microorganisms present cannot be determined. Accordingly, 25 kGy is used as the lethal dose for microorganisms in this study to calculate the required sterilization time. The radiation sterilization dose is calculated as follows:

|

4 |

In Eq. (4), DT is the radiation sterilization dose, HT is the standard sterilization dose of 25 kGy, and wR is the radiation weight factor of gamma rays, 120. Therefore, the radiation sterilization dose is 25 kGy. The sterilization time is:

|

5 |

In Eq. (5), d represents the energy deposited by a single photon, n represents the number of photons released per decay, and A represents the intensity of the photon. The 60Co source releases two gamma photons per decay. For a 60Co source used in medical sterilization devices, with an activity of 1.5 × 105 TBq43 and under the conditions specified (1 cm thick 60Co source, 20 cm thick cylindrical graphite reflector, 30 cm source-to-sample distance), the irradiation time for a single exposure of C group high-carbon steel samples (with layer sizes of 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2) was calculated to be 11.57 min. This means the total irradiation time of 23.14 min will be sufficient to achieve full sterilization of the surgical blades.

Moreover, suppose a more powerful 60Co source with an activity of 5.6 × 105 TBq, as permitted by the IAEA for medical sterilization devices43, is used. In that case, the sterilization time for medical surgical blades can be significantly reduced to 6.20 min. This reduction is due to the increased activity of the source, which releases more photons and, therefore, deposits more energy in a shorter time, achieving the required sterilization dose faster.

Conclusion

The results of the study suggest the energy deposited by single gamma photons in the high-carbon steel sample representing medical surgical blades is affected by several factors, including the energy and thickness of the radiation source, the material and thickness of the reflector, the shape of the reflector, the size of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample, and the source-to-sample distance.

In summary, compared to the hours-long chemical disinfection process for medical scalpels, The time required for irradiation sterilization can be decreased to 23.14 min by optimizing the irradiation facility model parameters with a 60Co source activity of 1.5 × 10⁵ TBq. Moreover, this time can be further shortened to 6.20 min when using a 60Co source activity of 5.6 × 10⁵ TBq, as permitted by the IAEA for medical sterilization devices and in accordance with the radiation sterilization dose standard. At this point, the gamma irradiation source is a 1 cm thick 60Co source, and the reflector is a cylindrical shell made of 20 cm thick graphite. The five layers of high-carbon steel sample layers from top to bottom measure 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2, with each layer having a thickness of 1 cm. The source-to-sample distance is 30 cm, and the energy deposited by a single photon used to calculate the single irradiation time in the middle layer II region is 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV. At this point, the sample’s DUR is 1.7, remaining below the maximum allowable value of 2.

This study still faces several challenges. Simplifying surgical blades into high-carbon steel layers with horizontal and vertical subdivisions based on stacking conditions introduces slight uncertainties in dose distribution. Additionally, the model disregards the actual packaging of surgical blades and the geometric characteristics of pencil sources, instead using simplified 60Co plates, which further impacts dose calculation accuracy. Furthermore, due to the limitations of the MCNP code, the temperature effects induced by irradiation were not considered. However, studies indicate that doses below 50 kGy have negligible effects on blade materials. Future work will focus on investigating the geometric characteristics of pencil sources and temperature effects to enhance the model’s accuracy.

Despite these challenges, this study presents a promising and practical method for improving the sterilization efficiency of disposable medical surgical blades and provides an essential reference for the broader application of irradiation sterilization technology in sterilizing medical instruments.

Author contributions

J.-W.B. performed most of the data analysis, prepared the figures, drafted the initial manuscript, and conducted preliminary revisions. F.L. led the project and contributed the conception and methodology. Y.-C.T. and Q.Z. consulted the references and assisted with revising the initial draft. X.-F.L. and J.-X.C. provided detailed explanations of the Monte Carlo method’s database. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Original data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu, Z., Wang, C., Chen, Z. & Sui, J. The advance of surgical blades in cutting soft biological tissue: a review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol.113, 1–16 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanghai Pudong Jinhuan Medical Supplies Co., LTD. Shanghai Institute of Medical Device Testing & Huaiyin Medical Equipment Co., LTD. Vol. YY/T 0174–2019 16 (National Medical Products Administration, 2019).

- 3.Surgical Blade Market Size. Share & Trends Anal. Rep. 150https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/surgical-blades-market (2024).

- 4.Garvey, M. Medical device-associated healthcare infections: sterilization and the potential of novel biological approaches to ensure patient safety. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.J, W. D. & A, R. W. & Sterilization of 20 billion medical devices by ethylene oxide (ETO): consequences of ETO closures and alternative sterilization technologies/solutions. Am. J. Infect. Control. 51, A82–A95 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sara, P. et al. 3D-printed PLA medical devices: physicochemical changes and biological response after sterilisation treatments. Polymers14, 4117–4117 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yiying, W. et al. Toxicity of ortho-phthalaldehyde aerosols in a human in vitro airway tissue model. Chem. Res. Toxicol.34, 754–766 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth, L. K. Center for Devices and Radiological Health Radiation Sterilization Master File Pilot Programhttps://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/04/12/2023-07598/center-for-devices-and-radiological-health-radiation-sterilization-master-filepilot-program (2023).

- 9.Schwartz, S. CDRH announces new standards recognition to support innovation in medical device sterilization. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/general-hospital-devices-and-supplies/sterilization-medical-devices (2023).

- 10.Brian, M. et al. Studies on the comparative effectiveness of X-rays, gamma rays and electron beams to inactivate microorganisms at different dose rates in industrial sterilization of medical devices. Radiat. Phys. Chem.208 (2023).

- 11.Mazhar, A., Hansi, N. S. E., Shafaa, M. W. & Shalaby, M. S. Radiation sterilization of liposomes: a literature review. Radiat. Phys. Chem.218, 111592 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanshika, V. K., Bhusan, M. B. & A. & Gamma irradiation enhanced flavor volatiles and selected biochemicals in onion (Allium cepa L.) during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol.209, 112690 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 inactivation simulation using 14 MeV neutron irradiation. Life11, 1372–1372 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torkamani, M. J. et al. Dose absorption of Omicron variant SARS-CoV-2 by electron radiation: using Geant4-DNA toolkit. Nucl. Eng. Technol.56, 2421–2427 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dagmara, C., Łukasz, W., Urszula, G. & Wojciech, M. Effect of electron beam irradiation on filtering facepiece respirators integrity and filtering efficiency. Nukleonika67, 23–33 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.BoTian et al. The structure and properties of medical disposable protective clothing materials with different packaging and models under γ irradiation. ChemistrySelect9 (2024).

- 17.Wang, B. et al. A study on radiation sterilization of medical products. J. Beijing Norm Univ. (Nat Sci), 24–31 (1987).

- 18.Sara, N., Robabeh, T., Hamid, N. & Samad, S. Experimental investigation of the electrical resistivity changes under irradiation by gamma rays from Cobalt-60 source. Indian J. Phys.97, 4169–4176 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakar, K. S., Noor, N. M., Hassan, M. F., Idris, F. & Bradley, D. A. Dose mapping in Cesium-137 blood irradiator using novel Ge-doped silica optical fibres in comparison with gafchromic EBT-XD film: a preliminary study. Radiat. Phys. Chem.209 (2023).

- 20.Liu, B., Xu, J., Liu, T. & Ouyang, X. Monte Carlo N-particle simulation of neutron-based sterilisation of anthrax contamination. Br. J. Radiol.85, e925–932. 10.1259/bjr/68583711 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan, X. et al. A simulation study on enhancing sterilization efficiency in medical plastics through gamma radiation optimization. Sci. Rep.13, 20289. 10.1038/s41598-023-47771-9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alda’ajeh, M. M., Sharaf, J. M., Saleh, H. H. & Hamideen, M. S. Determination of buildup factors for some human tissues using both MCNP5 and Phy-X / PSD. Nucl. Eng. Technol.55, 4426–4430. 10.1016/j.net.2023.08.025 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dridi, W., Daoudi, M., Farah, K. & Hosni, F. Monte Carlo validation of dose mapping for the Tunisian Gamma Irradiation Facility using the MCNP6 code. Radiat. Phys. Chem.17310.1016/j.radphyschem.2020.108942 (2020).

- 24.Jecong, J. F. M. et al. Ob-Servo Sanguis irradiator dose mapping at the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute using MCNP5 annular ring voxels. Radiat. Phys. Chem.19110.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109835 (2022).

- 25.Alruwaili, A. & Shalaby, M. S. The impact of NiWO4 on the enhancement of structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties of PVC nanocomposite films. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Electron.3510.1007/s10854-024-13932-3 (2024).

- 26.Abdel-Latif, M. A., Kaisy, A. M. M. A., Tawfic, A. M., Al-Shelkamy, S. A. & A. F. & Shielding and dosimetry parameters for aluminum carbon steel. Appl. Radiat. Isot.201, 111022. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2023.111022 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Didi, A. B., Dekhissi, H., Mohamed, Y. & Sebihi, R. Helium ion therapy compared to protons therapy using MCNP Monte-Carlo code. Annals Univ. Craiova Phys.30, 16–23 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdessamad, D. et al. Neutron and gamma flux distributions of an americium–beryllium facility: modelling and simulation. Mosc. Univ. Phys. Bull.78, 237–242 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan, C. White Los Alamos National Laboratory & Alamos, L. Photoatomic data library MCPLIB04: a new photoatomic library based on data from ENDF/B-VI Release 8 https://nucleardata.lanl.gov/files/la-ur-03-1019.pdf (2003).

- 30.Adams, K. J. Los Alamos National Laboratory & Alamos, L. Electron Upgrade for MCNP4B 2000 https://nucleardata.lanl.gov/files/la-ur-00-3581.pdf (2000).

- 31.Tyagi, G., Singhal, A., Routroy, S., Bhunia, D. & Lahoti, M. Radiation shielding concrete with alternate constituents: an approach to address multiple hazards. J. Hazard. Mater.404, 124201. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124201 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng, D., Gu, J. & Song, Y. MCNP simulating the apatial dose field of Cobalt-60 irradiation facility. J. Isot.35, 399–408 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng, D., Long, K., Qiu, X. & Liu, S. MCNP5 study on the absorbed dose of Cobalt-60 irradiation facility. J. Isot.32, 263–272 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabharwal, A. D., Sandhu, B. S. & Singh, B. Multiple backscattering on monoelemental materials and albedo factors of 279, 320, 511 and 662 keV gamma photons. Phys. Scripta. 8310.1088/0031-8949/83/02/025303 (2011).

- 35.Zuo, Y. H., Zhu, J. H. & Shang, P. Monte Carlo simulation of reflection effects of multi-element materials on gamma rays. Nucl. Sci. Tech.3210.1007/s41365-020-00837-z (2021).

- 36.Graphite Market Size. Share & Trends Anal. Rep. 120 https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/graphite-market-report (2023).

- 37.Graphite Procurement Intelligence Report. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/pipeline/graphite-procurement-intelligence-report (2022).

- 38.Lan, B. et al. Optimization of 60Coγ irradiation process for food. J. Radiat. Res. Radiat. Processin. 38, 56–63 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, C., Sun, X., Gu, J., Wang, G. & Bian, Y. Application and exploration of Radiation Disinfection Technology of sports equipment. China Port Sci. Tech.4, 66–71 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burt, M. M. & Ley, F. J. Studies on the dose requirement for the Radiation Sterilization of Medical Equipment. II. A comparison between continuous and fractionated doses. J. Appl. Bact.26, 490–492 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huynh, N., R, F. M. & F, M. D. A. & Sterilization of allograft bone: is 25 kGy the gold standard for gamma irradiation? Cell. Tissue Bank.8, 81–91 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine. vol. GB 16352 – 1996 28 (the State Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision (Ministry of Health of the PRC, 1996).

- 43.International Atomic Energy Agency. Categorization of Radioactive Sources, (2003).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.