Abstract

Purpose

Research on online active learning (OAL) in dental education has increased in recent years; however, this literature has yet to be comprehensively summarized to document the available evidence and identify research gaps. This scoping review aimed to comprehensively map the extent and depth of the research activity on OAL in undergraduate dental education.

Methods

The review adhered to Arksey & O'Malley's multi‐step framework and followed the PRISMA Extension Scoping Reviews guidelines. Searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and ERIC databases for peer‐reviewed primary research articles in English published between December 2013 and 2023. Four trained researchers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full‐text articles for eligibility and extracted relevant data. All activities and information were cross‐checked by the same researchers. A tested, methodologically‐informed form was used for data extraction. Descriptive statistics and content analysis were used to summarize the extracted data.

Results

Thirty‐five articles were included in the review. Most studies focused on dental students exclusively, with only two studies involving students and faculty. All studies performed outcome evaluations at reaction and/or learning levels. Problem‐based learning, case‐based learning, small group discussion, flipped learning, and blended learning were the most common active learning strategies employed. Dental students were satisfied with OAL and perceived it as beneficial for knowledge acquisition and skill development. Test results confirmed the improvement of knowledge through OAL.

Conclusion

OAL has shown to improve learning outcomes in dental education; however, robust research designs are needed to further demonstrate its effectiveness in this educational context.

Keywords: active learning strategies, distance learning, online active learning, undergraduate dental education

1. INTRODUCTION

Active learning has emerged as a transformative pedagogical approach across various fields of education. 1 , 2 Unlike passive styles of instruction, such as lectures and rote memorization, active learning promotes meaningful and deep learning by actively involving students in seeking, processing, and applying information. 2 Active learning has also been more favorably perceived by both faculty and students compared to passive learning. 3 Several strategies have been used to promote active learning across health professions education, including problem‐based learning, case‐based learning, flipped learning, team‐based learning, and group discussions. 3

Professional organization for dental education, such as the American Dental Education Association (ADEA), has continuously encouraged active learning to ensure that students exiting accredited dental programs have the competencies they need to provide effective dental care as entry‐level general dentists in the 21st century. 4 This recommendation has been based on the demonstrated effectiveness of this approach and its alignment with general principles of adult learning, such as self‐direction, purposefulness, experience and inquiry‐based learning, ownership, and intrinsic motivation. 5

Active learning is particularly important in dental education, where proficiency in complex skills and critical thinking is paramount. 6 Research has found that active learning promotes critical thinking, knowledge retention, and engagement in learning tasks in traditional face‐to‐face settings. 7 In clinical settings, active learning has proven effective in enhancing dental students’ clinical and diagnostic skills. 8

Active learning research in dental education has traditionally focused on face‐to‐face learning environments, particularly classroom education, where it has been perceived and proven effective in enhancing satisfaction with learning, knowledge acquisition, and skill development. 3 , 9 In recent years, several studies have been published on online undergraduate dental education due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, advancements in digital technologies, and the increased demand for flexible learning options. 10

This literature has not yet been summarized, underscoring the importance for documenting the type, amount, and variety of available evidence, as well as identifying research gaps. This scoping review aims to map the breadth and depth of research on online active learning (OAL) in undergraduate dental education.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

Our scoping review adhered to the original framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley, 11 encompassing five stages: (1) identifying the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. It was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR). 12

2.2. Research questions

We aimed to answer the following questions:

What are the main characteristics of studies on OAL in dental education in terms of publication details, participants, context, content area, and study design?

What active learning strategies were employed in these studies?

What were their main results?

2.3. Identification of relevant studies

The search strategies were developed in collaboration with an experienced librarian (LT) specialized in review studies in oral health education. A comprehensive search was initially conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid) and then adapted to the remaining three electronic databases, including Embase, Scopus, and ERIC. Table 1 shows the search strategy employed in this review. Our scoping review included primary studies on OAL in undergraduate dental education published in English within the last 10 years. To ensure comprehensive coverage, no restrictions were imposed regarding research inquiry (quantitative, qualitative, mixed‐methods), research design, type of active learning strategies in the online environment, type of user (students, instructors), or platforms used for online learning. Exclusions included studies published in languages other than English, non‐original research (e.g., commentaries, perspectives), articles lacking full‐text availability, studies not differentiating data between undergraduate dental students and students from other disciplines, and those not reporting evaluations of active learning strategies delivered online.

TABLE 1.

Detail of search terms and search results.

| Database | Terms and search strategy | |

|---|---|---|

|

MEDLINE by Ovid |

|

|

| Embase |

|

|

| ERIC |

S1 DE “Problem Based Learning” OR DE “Problem Solving” S2 (active OR team‐based OR case‐based OR problem‐based OR experience‐based OR outcome‐ based OR “small group*” OR participation* OR experiential OR cooperative OR role‐play* OR (interactive OR integrated) OR (student W1 (center* OR centre*)) OR (flipped N3 (classroom* OR learn*)) OR blended OR reflective OR “Integrated learning activity” OR peer OR “think pair share” OR TPS) OR TI (PBL or LBL or ILA or CBL or mcmaster) OR AB (PBL or LBL or ILA or CBL or mcmaster) S3 S1 OR S2 S4 DE “Dental Schools” OR (((dental OR dentistry) N3 (instruct* OR educat* OR learner* OR student* OR facult* OR school*))) S5 (DE “Distance Education” OR DE “Online Courses” OR DE “Virtual Classrooms” OR DE “Virtual Schools” OR DE “Virtual Universities” OR DE “Web Based Instruction”) OR (cyber or digital or distance learning* or tele or remote* or sms or internet or “web based” or online* or Facetime or “Google Meet” or GMeet* or hangout* or Skype or Zoom or Web‐ex or WebEx or Facebook or “e chat” or echat or e‐learning or e‐seminar* or e‐class* or synchronous or asynchronous or “text message*” or “video conferenc*” or “video link*” or “video chat*” or virtual or videoconferen*) S6 (S3 AND S4 AND S5) |

|

| Scopus | ((TITLE‐ABS‐KEY (active OR team‐based OR case‐based OR problem‐based OR experience‐based OR outcome‐based OR “small group” OR “small groups” OR participation* OR experiential OR cooperative OR role‐play* OR interactive OR integrated OR blended OR reflective OR “integrated learning activity” OR peer OR “think pair share” OR tps) OR TITLE (pbl OR lbl OR ila OR cbl OR mcmaster) OR ABS (pbl OR lbl OR ila OR cbl OR mcmaster) OR TITLE‐ABS‐KEY ((student W/2 (center* OR centre*))) OR TITLE‐ABS‐KEY ((flipped W/3 (classroom* OR learn*))))) AND ((TITLE‐ABS‐KEY ((dental OR dentistry) W/3 (instruct* OR educat* OR learner* OR student* OR facult*)) OR TITLE‐ABS‐KEY (dentistry W/1 school*))) AND (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY ((cyber OR digital OR “distance learning” OR “distance education” OR tele OR remote* OR sms OR internet OR “web based” OR online* OR facetime OR “google meet” OR gmeet* OR hangout* OR skype OR zoom OR web‐ex OR webex OR facebook OR “e chat” OR echat* OR e‐learning* OR e‐seminar* OR e‐class* OR synchronous OR asynchronous OR (text W/1 message*) OR (video W/1 (conference* OR link* OR chat*)) OR virtual OR videoconferen*))) AND PUBYEAR > 2012 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 | |

2.4. Study selection

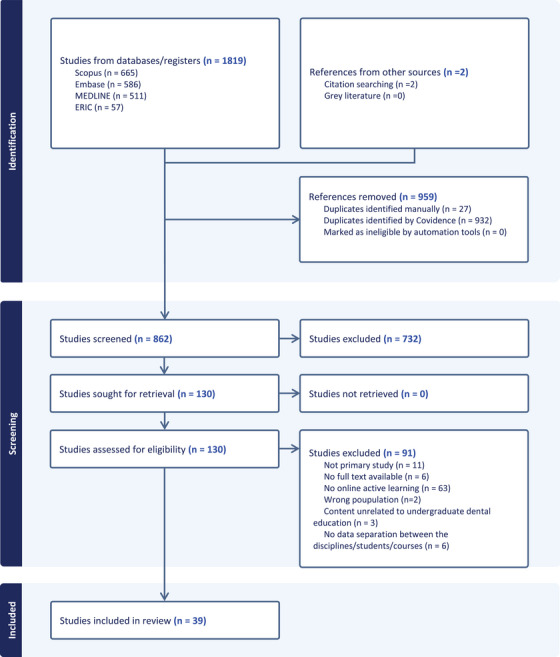

The search results from all four databases were exported to Covidence 13 by the librarian (LT). Duplicated studies identified automatically by Covidence and then manually by the researchers were removed. Eligible articles were screened independently by two researchers (ZA and NS) based on titles and abstracts. Following this initial screening, two pairs of researchers (ZA and NS, CS and AL) independently examined full articles to identify eligible papers. A training session was conducted on 5% of the eligible articles to ensure consistency in the screening process. Discrepancies in study selection were resolved through discussion among researchers or, when necessary, in consultation with another researcher (AP). The reasons for excluding full‐text articles are documented in Covidence and presented in Figure 1. Additionally, three researchers (NS, CS, AL) hand‐searched the references of the included articles to identify additional relevant studies.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

2.5. Data charting

A data extraction form recommended for scoping reviews was utilized and tested before data charting. 14 Four researchers (ZA, NS, CS, AL) independently extracted relevant data from eligible papers using the Covidence software. All retrieved information was cross‐checked by a second independent researcher.

2.6. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Descriptive statistics were employed to provide numerical summaries of study characteristics and OAL strategies. Content analysis was utilized to summarize the results of selected studies, which were sorted into categories representing levels of outcome evaluation suggested in using Kirkpatrick's framework 15 particularly reaction and learning outcome levels. Absolute and relative frequencies were used to quantify findings within these categories.

3. RESULTS

The search yielded 1819 records, including 511 from MEDLINE, 586 from Embase, 665 from Scopus, and 57 from ERIC. The duplicates (n = 959) were subsequently removed. The initial screening based on titles and abstracts identified 128 potentially eligible articles, of which thirty‐three met the eligibility criteria after full‐text screening. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 Two additional papers were identified by checking the references of eligible articles. 49 , 50 In total, 35 articles were included in this review (Table 2). Figure 1 depicts the screening process.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Authors/publication year/country | Study participants (sample size) | Data collection strategy |

Type of online active learning (OAL) |

Comparison | Level of outcome evaluation | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alharbi et al. 2022, Saudi Arabia | Students (n = 32) | survey, test | Virtual flipped learning, case‐based learning | OAL vs. online passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Students were more satisfied with OAL vs. online passive learning. There was no difference between OAL and passive learning regarding measured knowledge |

| Amir et al. 2020, Indonesia | Students (n = 301) | Survey | Collaborative learning, question‐based learning, problem‐based learning | OAL vs. in‐person active learning | Reaction | Perceived OAL superior to in‐person active learning regarding knowledge. OAL found inferior to in‐person active learning regarding satisfaction. |

| Ariana et al.2016, Australia | Students (n = 194) | Survey, test | Blended learning, virtual interactive microscopy | OAL vs. in‐person active and passive learning |

Reaction learning |

OAL superior to in‐person passive learning in knowledge acquisition. Satisfaction was improved in the in‐person active learning. |

| Arus et al. 2017, Brazil | Students (n = 37) | Survey, test | Lab self‐oriented learning | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Students satisfied with OAL. In‐person passive learning was superior to AOL in knowledge acquisition. Measured Knowledge was improved in both groups. |

| Cho and Ganesh 2022, USA | Students (n = 134) | Survey, test | Blended learning | No comparison |

Reaction learning |

Perceived improvement in knowledge acquisition and skill development including assessment and treatment planning though OAL. Measured improvement in knowledge acquisition. |

| Dalal et al. 2022, USA | Students (n = 90) | Survey | Think‐pair‐share, brain dump, group discussions, small group presentations, role playing/games, peer teaching, concept maps, cases, debates, jigsaw, problem‐based learning | OAL vs. in‐person active learning | Reaction | Perceived no difference in satisfaction between OAL and in‐person active learning |

| Ezra et al. 2021, Indonesia | Students (n = 103) | Survey | Problem‐based learning | No comparison | Reaction | Perceived knowledge gain through OAL |

| Fadel et al. 2021, Saudi Arabia | Students (n = 76) | Survey, test | Flipped classroom | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

OAL equal to in‐person passive learning regarding perceived knowledge. No difference between in‐person passive learning vs. OAL regarding satisfaction and measured knowledge acquisition |

| Farokhi et al. 2023, USA | Students (n = 210) | Survey | Flipped classroom | OAL vs. in‐person active learning | Reaction | Satisfied with OAL; perceived skill development through OAL regarding communication and case analysis. |

| Inamochi et al. 2023, Japan | Students (n = 195) | Test | Team‐based learning | OAL vs. in‐person passive and active learning |

Learning |

OAL superior to in‐person passive learning regarding knowledge acquisition. OAL superior to active in‐person active learning regarding knowledge acquisition |

| Jabbour and Tran 2023, USA | Students (n = 106) | Survey, test | Case‐based learning | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Satisfied with OAL. Perceived knowledge gain. OAL improved measured skill development in case assessment and competency compared to in‐person passive learning |

| Jiang et al. 2021, China | Students (n = 104) | Survey | Problem‐based learning, research‐based learning, case‐based learning, team‐based learning | OAL vs. online passive learning | Reaction | OAL equal online passive learning regarding satisfaction. |

| Karaca et al. 2022, Turkey | Students (n‐83) | Survey, test | enriched virtual classroom | OAL vs. online passive learning |

Reaction learning |

OAL superior to online passive learning regarding measured knowledge acquisition. OAL superior to online passive learning regarding satisfaction. |

| Lim et al. 2022, Korea | Students (n = 114) | Survey, test | Lecture and discussion, self‐study and discussion | OAL vs. another OAL | Learning | OAL improved measured knowledge |

| Menon et al. 2022, Malaysia |

Students (n = 35) faculty NR |

Survey | Think aloud | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfied with OAL |

| Messina et al. 2022, USA | Students (n = 240) | Survey, test | Interactive Nearpod review | OAL vs. in‐person active learning |

Reaction learning |

Satisfied with OAL. OAL superior to in‐person active learning regarding measured knowledge acquisition |

| Moazami et al. 2014, Iran | Students (n = 35) | Test | Self‐paced Learning (in virtual environment with different activities) | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning | Learning | OAL superior to in‐person passive learning regarding measured knowledge acquisition. |

| Mohd Suria et al. 2023, Malaysia | Students (n = 68) | Survey, test, written reflection | Online peer‐assisted learning | No comparison |

Reaction learning |

Satisfaction with OAL. OAL improved measured knowledge gain. |

| Mucke et al. 2023, Germany | Students (n = 205) | Test | Online seminars | OAL vs. in‐person active learning | Learning | OAL equal in person active learning regarding measured knowledge acquisition. |

| Oetter et al. 2022, Germany | Students (n = 300) | Survey | Demonstration and following along | No comparison |

Reaction |

Satisfied with OAL. Perceived knowledge gain through OAL perceived surgical skills development through OAL |

| Oliveira et al. 2019, USA | Students (n = 49) | Survey, test | Case‐based learning | No comparison |

Reaction learning |

OAL improved knowledge acquisition. OAL perceived knowledge and skill developments (surgical skills). Student satisfied with OAL. |

| Ostermann et al. 2017, Germany | Students (n = 60) | Test | Case‐based learning | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Learning |

OAL vs. in‐person passive learning. OAL superior in measured knowledge and skill development (cases assessment) |

| Paudel et al. 2021, Nepal | Students (n = 22) | Survey, tests | Problem‐based learning, tutoring | No comparison |

Reaction learning |

Satisfaction with OAL and OAL improving measured knowledge acquisition |

| Quos et al. 2017, Germany | Students (n = 121) | Survey | Case‐based learning | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfaction with OAL. |

| Rath et al. 2021, Malaysia | Students (n = 50) | Survey | Blended learning, drawing | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfaction with OAL. |

| Shapiro et al. 2014, USA | Students (n = 72) |

Survey, test |

Interactive learning with instant feedback | OAL vs. in person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Satisfaction with OAL. OAL is superior to in‐person passive learning in terms of measured knowledge gain. |

| Soltanimehr et al. 2019, Iran | Students (n = 39) | Test | Self‐paced learning (in virtual environment with different activities) | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning | Learning | OAL superior to in‐person passive learning regarding measured knowledge acquisition and equal to in‐person passive learning regarding clinical skills (radiographic interpretation of bony lesions). |

| Tariq et al. 2023, Pakistan | Students (n = 9) | Focus groups | Small group discussions | No comparison |

Reaction |

Satisfaction with AOL and AOL improving perceived knowledge acquisition. |

| Tee et al. 2022, Malaysia | Students (n = 51) | Survey, interview, test, focus groups | Case‐based learning in virtual interactive format and virtual role playing | OAL vs. another OAL |

Reaction learning |

Satisfied with OAL; positive attitude toward oal measured improvement regarding knowledge gain, skill development, (e.g., critical thinking, communications skills, diagnostic skills, decision making skills) |

| Thor et al. 2017, USA | Students (n = 142) | Survey, interview | Small groups presentations and discussions | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfied with OAL; positive attitude toward AOL |

| Ullah et al. 2021, Pakistan | Students (n = 93) | Survey, test | Group discussions | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Satisfaction with OAL. Perceived and measured knowledge gain through OAL. OAL is superior to in‐person passive learning regarding measured knowledge gain. |

| Veeraiyan et al. 2022, India | Students (n = 49) | Test | Concept mapping, quizzes, role playing, puzzle, and crosswords | OAL vs. in‐person active learning | Learning | No difference between OAL and in‐person active learning regarding measured of skill development (hand skills in periodontics). |

| Yu‐Fong Chang et al. 2021, Taiwan | Students (n = 34) | Survey, test | Small group discussions | OAL vs. in‐person passive learning |

Reaction learning |

Satisfaction with OAL. Equal to in person passive learning regarding measured knowledge gain and skill development (diagnostic skills). |

| Zhang et al. 2019, China |

Students (n = 72) Faculty (n = 10) |

Survey | Problem‐based learning | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfied with OAL; positive attitude toward OAL. |

| Zheng et al. 2017, USA | Students (n = 124) | Survey, interview | Peer and instructor discussions | No comparison | Reaction | Satisfied with OAL; positive attitude toward OAL regarding perceived knowledge gain. |

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

The included studies originated from Asia (n = 20, 57.1%), North America (n = 9, 25.7%), Europe (n = 4, 11.4%), South America (n = 1, 2.9%), and Oceania (n = 1, 2.9%) (Figure 2A). Almost two‐thirds of the studies between 2013 and 2023 were published from 2021 onward (Figure 2B). Most studies involved undergraduate dental students (n = 33, 94.3%), and only two (5.7%) involved students and faculty. 30 , 47 Of the included studies, 28 (80%) were quantitative, 6 (17.1%) were mixed‐methods, 24 , 26 , 32 , 42 , 46 , 48 and only 1 (2.9%) was qualitative (Figure 2C). 41 Only a third (n = 10) of the selected studies reported their study methods. Reported methods included randomized controlled trials (n = 3), 16 , 28 , 42 cross‐sectional studies (n = 2), 27 , 45 quasi‐experimental (n = 2), 23 , 31 descriptive (n = 1), 22 exploratory (n = 1), 43 and experimental (n = 1). 50

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of included papers (n = 35) according to (A) country of publication; (B) number of published papers per year; (C) methodological approach used; and (D) sample composition (figure created with www.mapchart.net, and www.canva.com).

Regarding the sciences that constitute the main components of dental education, 24 (68.6%) of the included studies reported on OAL in clinical sciences, seven (20%) in basic sciences, two (5.6%) in behavioral and social sciences, and one (2.9%) did not report the content area. Only one article (2.9%) investigated OAL in both basic and clinical sciences. Overall, these studies involved 3659 participants with the majority (n = 3649, 99.7%) being undergraduate dental students. Only one of the two studies involving faculty members indicated the number of participants (n = 10, 0.3%). 47

3.2. Platforms and online active learning strategies employed

Twenty‐three studies (65.7%) indicated the platform used for OAL. The most commonly used platforms were Zoom (n = 6) and Microsoft Teams (n = 4). Other platforms used included Google Meet, WebEx, Blackboard, Adobe Illustrator, Voice Thread, university‐specific learning management systems, and WeChat. These platforms were mostly used for real‐time communications and interactions between student groups and instructors.

The most common OAL strategies investigated were problem‐based learning (n = 7, 20%), case‐based learning (n = 5, 14.3%), small group discussion (n = 4, 11.4%), flipped learning (n = 4, 11.4%), blended learning (n = 4, 11.4%). Strategies evaluated in only one study included collaborative learning, lab self‐oriented learning, team‐based learning, think‐aloud, interactive nearpod review, and peer‐assisted learning.

3.3. Evaluations performed in the included studies

All studies conducted outcome evaluations, and none performed process evaluations. Outcome evaluations were performed at reaction and learning levels. Fifteen studies (42.9%) performed reaction and learning evaluations combined, 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 42 , 44 , 46 13 (37.1%) reaction evaluations alone, 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 30 , 34 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 48 7 (20%) learning evaluations alone. 25 , 29 , 33 , 36 , 45 , 49 , 50 Learning satisfaction (n = 26) and knowledge acquisition (n = 25) were the main outcomes evaluated, followed by skill development (n = 10).

A total of 22 studies involved comparisons and 13 did not. In the comparative studies, OAL was compared to in‐person passive leaning (n = 9, 40.9%), 18 , 22 , 25 , 35 , 39 , 43 , 45 , 48 , 49 in‐person active learning (n = 6, 27.3%), 17 , 21 , 24 , 31 , 33 , 45 and online passive learning (n = 3, 13.6%). 16 , 27 , 28 Two studies (9%) compared OAL with both passive and active in‐person learning. 18 , 25 The remaining two (9%) compared two active learning strategies. 29 , 42

Among the 13 non‐comparative (single group) studies, 9 studies included a post‐intervention evaluation, 22 , 30 , 34 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 48 while only 4 studies included a pre‐post intervention evaluation. 20 , 32 , 35 , 37 Within the comparative group of studies (n = 22), 14 studies included a post‐intervention evaluation 17 , 18 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 45 , 46 , 50 and 8 studies included a pre‐post intervention evaluation. 16 , 19 , 23 , 28 , 40 , 42 , 44 , 49

3.4. Key findings of the included studies by level of evaluation

3.4.1. Reaction level evaluation

All 11 non‐comparative studies evaluating the impact of OAL on perceived learning satisfaction, 30 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 48 as well as all six studies evaluating its impact on perceived knowledge acquisition, 20 , 22 , 34 , 35 , 41 , 48 reported improvements in these outcomes. Similarly, all three non‐comparative studies that evaluated perceived skill development found that OAL improved this outcome, specifically diagnostic, treatment planning, and surgical skills. 20 , 34 , 35

Among six studies comparing learning satisfaction between OAL and in‐person passive learning, five found OAL superior, 19 , 26 , 40 , 44 , 46 while one noted no difference. 23 In terms of perceived knowledge acquisition, four out of six studies favored OAL over in‐person passive learning, 18 , 25 , 26 , 44 one was inferior 19 and one reported no differences. 23 No study compared perceived skill development between these teaching modalities. Interestingly, four studies compared learning satisfaction between online and in‐person active learning, of which two found OAL inferior, 17 , 18 one reported it as superior, 31 and one found no differences. 21 The sole study comparing perceived knowledge acquisition between these modalities found OAL to be superior. 17 Of three studies comparing learning satisfaction between active and passive online learning, two favored the active approach, 16 , 28 and one found no differences. 27 Only one study compared perceived skill development between OAL and in‐person active learning strategy 24 founding OAL superior.

Faculty expressed satisfaction with OAL, noting increased general knowledge and analytical skills through problem‐based learning. 47 However, they identified challenges and areas for improvement in implementing the think‐aloud learning strategy, emphasizing the need for training faculty to use this strategy effectively. Additionally, they recommended implementing post‐session assessments to properly evaluate knowledge gains among students. 30

3.4.2. Learning level evaluation

All four non‐comparative studies assessing the impact of OAL on knowledge acquisition reported improvements in this outcome. 20 , 32 , 35 , 37 No non‐comparative studies assessed the impact of OAL on skills development.

Seven studies compared assessed knowledge acquisition between OAL and in‐person passive delivery modalities, with three finding OAL superior, 18 , 36 , 40 , 44 , 50 one inferior, 19 and one reporting no differences. 46 Additionally, four studies compared assessed skill development between OAL and in‐person passive learning, with two finding the former superior 26 , 36 and two noting no differences 46 , 50 in terms of diagnostic skills, including the interpretation of radiographic images. Similarly, two out of three studies comparing online and in‐person active learning found the former superior 25 , 31 and one did not report differences in knowledge acquisition. 33 Only one study compared assessed skill development between these two delivery modalities, reporting no differences in psychomotor skills. 45 No study compared assessed learning, knowledge acquisition, or skill development between active and passive online learning. Two studies compared different active learning strategies delivered online. 29 , 42 One study found that self‐study and discussion without a worksheet were superior to self‐study and discussion with worksheet in terms of assessed knowledge acquisition. 29 The other study compared digital interactive case‐based learning with virtual role play. 42 While both strategies were effective in enhancing communication, diagnostic and decision‐making skills, the digital case‐based learning was found superior.

4. DISCUSSION

This review aimed to summarize the available literature on OAL in undergraduate dental education to identify research gaps, which are summarized in Table 3. Most studies conducted in the study period used quantitative designs and involved undergraduate dental students. All included studies conducted performed outcome evaluations at the reaction and/or learning levels. The main learning outcomes considered in these studies were learning satisfaction and knowledge acquisition followed by skill development. Both non‐comparative and comparative studies suggest that OAL has potential to improve theses three outcomes. This review represents the first attempt to systematically and comprehensively map the literature on OAL in undergraduate dental education which is important to inform future research endeavors.

TABLE 3.

Identified gaps in the literature on online active learning (OAL) in dental education.

| Need for studies: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of the included studies in this review were descriptive, quantitative and performed post‐intervention evaluations, which previous research on in‐person active learning in dental education has also reported. 3 , 9 Best practices in curriculum evaluation suggest the use of multiple evaluators, quantitative and qualitative data, evaluation frameworks, and robust designs to uncover the interplay of factors leading to specific outcomes and to accurately measure those outcomes. 51 For example, interventional studies without proper controls are ill‐suited to account for the influence of known and unknown confounding factors. Similarly, evaluation questions may not be fully answered without using qualitative data to interpret quantitative findings, which mixed‐methods research can effectively accomplish. Additionally, qualitative research helps understand the actions and interactions of those involved in teaching and learning processes, 52 offering insights into strengths and limitations of educational intervention, as well as potential solutions to address these limitations in specific contexts.

Similar to our findings, systematically conducted reviews in medical education have reported that most studies on OAL involve students exclusively with a few including faculty. 53 , 54 Faculty perspectives are important to provide a nuanced, comprehensive understanding of teaching effectiveness, especially in relatively new learning environments and modalities (e.g., online clinical education). While the involvement of students allows for the evaluation of perceived and factual learning, students generally are not in a position to evaluate key dimensions of teaching effectiveness such as content integration and the suitability of teaching strategies to achieve certain learning outcomes. 55 Additionally, faculty perspectives on OAL can provide valuable insights into the circumstances in which it works and their uptake of this teaching modality. 3 For example, in a study evaluating the think aloud strategy to support clinical learning in dental education, 30 students primarily commented on learning satisfaction and required knowledge, while faculty also highlighted the need for further assessments, calibration in both content delivery and assessment, and additional training for the effective delivery of OAL. Interestingly, a study comparing university students’ and faculty's views across disciplines on online distance education found that while both groups shared similar positive and negative views, faculty were more critical, identifying additional issues that needed to be addressed. 56

Evaluations of active learning across health professions education have mostly been conducted at the reaction and learning levels, 3 which aligns with our findings. These two levels of evaluation are important because they provide insight into students’ learning experiences and their actual learning when measured through validated tools. However, they provide limited insight into how well students apply the knowledge and skills learned in classroom and simulation settings to clinical practice (behavioral level) and the impact of novel educational interventions, including OAL, on organizational outcomes (result level). Similar to research on in‐person active learning in dental education, 3 we found that most studies included in our review focused on learning satisfaction and knowledge acquisition as the main outcomes. Thus, research is needed to further assess the impact of OAL on the skill development using direct outcome measures, which is well‐aligned with the competency‐based approach for teaching and assessment that has been highly recommended in dental education. 7

Despite the increased digitalization of dental education, 57 few active learning strategies, including problem‐based learning, case‐based learning, small group discussion, flipped learning, and blended learning, have been tested in this environment. Demonstrating the effectiveness of these active learning strategies and generating evidence about the effectiveness of additional strategies will provide dental educators with options to select or combine to achieve learning objectives in digital dental education. Dental educators can also benefit from developments in OAL in other disciplines, such as medicine and nursing, as long as they aim to achieve similar learning objectives under relatively similar circumstances, including settings and student characteristics.

The findings of both non‐comparative and comparative studies included in our review suggest that OAL is potentially effective in improving important learning outcomes such as learning satisfaction, knowledge acquisition, and, to some extent, skill development. These findings are consistent with those of previous reviews on active learning in in‐person, classroom dental education, whether targeting multiple or single strategies. 3 , 9 , 58 , 59 For instance, a recent review mapping active learning in this environment found that it positively impacted learning satisfaction and knowledge acquisition across strategies, and was largely superior to traditional lectures based on both perceived and assessed outcome measures. 3 Particularly, a review study focusing on problem‐based learning in dental education documented that this strategy improved students’ capacity to apply their knowledge in clinical scenarios and had a positive impact on their perceived readiness for clinical practice. 60 Furthermore, a systematic review, including a meta‐analysis, found that case‐based learning enhanced knowledge, skill, and ability scores, as well as students’ satisfaction. 58 Similarly, another systematic review reported that dental students had a positive view of flipped learning and perceived it as effective for knowledge acquisition. 61 Such consistent evidence suggests that active learning has the potential to achieve traditional learning outcomes regardless of whether it is delivered in‐person or online. Considering the specifics of online education in engaging students in active learning, the extent to which dental educators are well‐equipped to undertake this challenge remains to be elucidated.

Our review highlights the need for further research comparing active learning strategies delivered online, as only two studies performed these comparisons during the study period. Given that active learning strategies may serve different purposes, it is crucial to establish the conditions under which they are effective in online dental education, the learning outcomes they promote, and their relative effectiveness, especially among strategies serving similar educational purposes. For example, what is the relative effectiveness of case‐based learning versus problem‐based learning in promoting critical thinking in online dental education? How does online team‐based learning compare to group discussion in fostering communication skills in dental students?

The perceived and assessed positive learning outcomes of OAL identified in this review should be considered in the context of the advantages and disadvantages attributed to this learning modality. Besides these positive outcomes, OAL in dental education and health professions education at large have several advantages, such as improved accessibility to recorded learning sessions and online resources, promotion of technology‐based collaboration and peer discussion, flexible work‐life balance, opportunities for interactive activities, and effective use of time (e.g., avoiding commuting time). 46 , 54 However, disadvantages and challenges have been observed for both faculty and students. 46 , 53 ,54Faculty‐related disadvantages include a lack of digital competency, inexperience in delivering OAL, difficulty in building rapport, inability to read body language and make necessary adjustments, and increased time required to create learning materials and resources. Reported disadvantages for students include technical issues, distractions, limited interaction, difficulties in managing pre‐class workload, and disengagement from peer sharing and presentations. Several recommendations related to logistics, competency, content, delivery/teaching, and assessment have been suggested to capitalize on the advantages and address the disadvantages of OAL, 24 , 53 , 54 , 62 which are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Recommendations for implementing online active learning (OAL).

| Logistics |

|

| Competency |

|

| Content |

|

| Delivery/teaching |

|

| Assessment |

|

Some limitations of our scoping review need to be acknowledged. First, we only included papers published in English, which may limit the generalizability of our study findings. Second, the methodological quality of the included quantitative, mixed‐methods and qualitative studies was not assessed in accordance with the chosen review framework. The effect of an intervention may be due to its ‘intrinsic effectiveness’ or to other factors, including the quality of the studies conducted. Research in health professions education suggests that low quality research, particularly from single‐group pre‐/post‐test studies, may overestimate the effect sizes of online educational interventions. 63 Thus, the weak designs employed for evaluating perceived and actual learning (e.g., post‐intervention evaluation), coupled with the lack of reported methodologies guiding the research design in many studies, suggest that the evidence generated is neither sufficient not conclusive to establish the effectiveness of OAL in dental education. This issue is not unique to dental education; similar concerns have been observed in medical education. 64 Insufficient methodological details and lack of reported research methodologies are problematic, as methodologies are essential for informing all the components of a research design (e.g., participants, data collection, data analysis, criteria of rigor) and effectively answering research questions. 65 Lastly, the diversity of study designs, active learning strategies, platforms, learning outcomes, and levels of evaluation posed a significant challenge to summarize the breadth and depth of the research activity on OAL in dental education. Further research using direct outcome measures is warranted to establish the effectiveness of various active learning strategies in online dental education, not only in terms of learning satisfaction and knowledge acquisition but also in skill and competency development and behavioral change. Future studies should also explore the perspectives of dental educators regarding OAL to gain insights into its, strengths and shortcomings, including potential solutions. Qualitative research approaches, particularly qualitative description 66 and interpretative description 67 can be used for this purpose. Additionally, conducting process evaluations to assess the extent to which active learning was delivered online as expected, along with evaluations at learning behavioral and organizational levels using experimental, quasi‐experimental, and observational designs with one or more cohorts, will provide a more complete picture of the potential of OAL in an increasingly digitalized dental education. 68 Given that online platforms have different functionalities, researchers should examine whether not only the chosen active learning strategy but also the platform itself affects learning outcomes in online dental education. Table 3 summarizes the identified research gaps in this review.

5. CONCLUSION

Dental students positively perceived OAL to enhance learning satisfaction, knowledge acquisition, and skills development, with direct measures confirming the positive impact of OAL on knowledge acquisition. Robust designs are necessary to establish the effectiveness of OAL across various strategies, learning outcomes, and levels of outcome evaluation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the School of Dentistry at the University of Alberta for its financial support, the Educational Research & Scholarship Unit for providing methodological assistance throughout the study, and the Health Science Library for its services. The authors received funding (SDERF) for this work from the School of Dentistry at the University of Alberta.

Apel Z, Sharmin N, Stefani CM, et al. Online active learning in undergraduate dental education: A scoping review. J Dent Educ. 2025;89:320–336. 10.1002/jdd.13721

REFERENCES

- 1. Carvalho H, West CA. Voluntary participation in an active learning exercise leads to a better understanding of physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2011;35(1):53‐58. doi: 10.1152/advan.00011.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gülpinar MA, Yeğen DBÇ. Interactive lecturing for meaningful learning in large groups. Med Teach. 2005;27:590‐594. doi: 10.1080/01421590500136139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perez A, Green J, Moharrami M, et al. Active learning in undergraduate classroom dental education‐ a scoping review. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0293206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palatta AM, Kassebaum DK, Gadbury‐Amyot CC, et al. Change is here: aDEA CCI 2.0—a learning community for the advancement of dental education. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(6):640‐648. doi: 10.21815/JDE.016.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lippitt GL, Knowles MS, Knowles MS. Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Learning. Jossey‐Bass; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prince M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J Eng Educ. 2004;93(3):223‐231. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. ADEA Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education , Pyle M, Andrieu SC, et al, ADEA Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education . The case for change in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(9):921‐924. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2006.70.9.tb04162.x 16954413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puranik CP, Pickett K, de Peralta T. Evaluation of problem‐based learning in dental trauma education: an observational cohort study. Dent Traumatol. 2023;39(6):625‐636. doi: 10.1111/edt.12870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vanka A, Vanka S, Wali O. Flipped classroom in dental education: a scoping review. Eur J Dental Educ. 2020;24(2):213‐226. doi: 10.1111/eje.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ali K, Alhaija ESA, Raja M, et al. Blended learning in undergraduate dental education: a global pilot study. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1):2171700. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2171700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Covidence—better systematic review management. Covidence. Accessed June 24, 2024. https://www.covidence.org/

- 14. Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):520. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falletta S. Evaluating training programs: the four levels (Kirkpatrick DL. Berrett‐Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1996: 229). Am J Eval. 1998;19:259‐261. doi: 10.1016/S1098-2140(99)80206-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alharbi F, Alwadei SH, Alwadei A, et al. Comparison between two asynchronous teaching methods in an undergraduate dental course: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):488. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03557-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amir LR, Tanti I, Maharani DA, et al. Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID‐19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):392. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ariana A, Amin M, Pakneshan S, Dolan‐Evans E, Lam AK. Integration of traditional and E‐learning methods to improve learning outcomes for dental students in histopathology. J Dent Educ. 2016;80(9):1140‐1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arus NA, da Silva AM, Duarte R, et al. Teaching dental students to understand the temporomandibular joint using MRI: comparison of conventional and digital learning methods. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(6):752‐758. doi: 10.21815/JDE.016.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cho A, Ganesh N. Dental students’ perception of a blended learning approach to clinic orientation. J Dent Educ. 2022;86(6):721‐725. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dalal AR, Joy‐Thomas AR, Quock RL. Effect of shift to virtual teaching on active learning: a snapshot. J Dent Educ. 2022;86(8):976‐989. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ezra N, Kusumo AD, Ag KF, et al. Dental medicine students perception on the effectiveness of problem based learning (PBL) class using online learning method. Medico‐Legal Update. 2021;21(2):870‐874. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fadel HT, Khalifah AM, Znadah WA. Sudden introduction of a flipped classroom framework involving face‐to‐face and synchronous active learning strategies to undergraduate dental students: a quasi‐experimental study. 2021:63‐69. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2‐s2.0‐85105883067&partnerID=40&md5=aac3bbdfe8fdbb8a3964da0d6945db23

- 24. Farokhi MR, English DK, Boone SL, Amaechi BT. Health professions learners’ evaluation of e‐learning scenario‐based case study design: reinvigorating flipped classroom modalities. J Dent Educ. 2023;87(12):1754‐1765. doi: 10.1002/jdd.13379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inamochi Y, Kohno EY, Wada J, et al. Knowledge acquisition efficacy of a remote flipped classroom on learning about removable partial dentures. J Prosthodont Res. 2023;67(3):444‐449. doi: 10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_22_00147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jabbour Z, Tran M. Can students develop clinical competency in treatment planning remotely through flipped collaborative case discussion? Eur J Dent Educ. 2023;27(1):69‐77. doi: 10.1111/eje.12778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jiang Z, Zhu D, Li J, Ren L, Pu R, Yang G. Online dental teaching practices during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional online survey from China. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01547-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karaca O, Cinarcik BS, Asik A, et al. Impact of fully online flipped classroom on academic achievement in undergraduate dental education: an experimental study. Eur J Dent Educ. 2023;28(1):212‐226. doi: 10.1111/eje.12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim J, Ko H, Park J, Ihm J. Effect of active learning and online discussions on the academic performances of dental students. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03377-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Menon RK, Bhatia S, Nadarajah VD, Pau A. Piloting online “Think Aloud” sessions to support clinical learning during the pandemic. Educ Med J. 2022;14(2):93‐102. doi: 10.21315/eimj2022.14.2.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Messina DM, Mikhail SS, Messina MJ, Novopoltseva IA. Assessment of learning outcomes of first year dental students using an interactive Nearpod educational platform. J Dent Educ. 2022;86(7):893‐899. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mohd Suria TYI, Omar AF, Wan Mokhtar I, Rahman ANAA, Kamaruddin AA, Ahmad MS. Special care dentistry education during the COVID‐19 pandemic: the impact of online peer‐assisted learning. Spec Care Dentist. 2023;43(6):848‐855. doi: 10.1111/scd.12857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mucke K, Busch C, Becker J, Drescher D, Becker K. Is online‐only learning as effective as blended learning? A longitudinal study comparing undergraduate students’ performance in oral radiology. Eur J Dent Educ. 2023;28(1):236‐250. doi: 10.1111/eje.12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oetter N, Most T, Weber M, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and its impact on dental education: digitalization—progress or regress? BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):591. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03638-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oliveira ER, Rose WF, Hendricson WD. Online case‐sharing to enhance dental students’ clinical education: a pilot study. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(4):416‐422. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ostermann T, Ihlhoff‐Goulioumius H, Fischer MR, Ehlers JP, Zupanic M. Implementation and Empirical Evaluation of a Case‐Based, Interactive e‐Learning Module with X‐ray Tooth Prognosis. SciTePress; 2017:277‐281. doi: 10.5220/0006475302770281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paudel S, Subedi N, Sapkota S, Shrestha B, Shrestha S. Perception of problem based learning by undergraduate dental students in basic medical science. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2021;19(2):384‐389. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v19i2.3458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quos M, Ruttermann S, Gerhardt‐Szep S. Cross‐year peer‐assisted learning using the inverted (“flipped”) classroom design: a pilot study in dentistry. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2017;126(101477604):84‐93. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rath A, Sidhu P, Wong M, Pannuti C. The impetus to interactive learning: whiteboarding for online dental education in COVID‐19. J Dent Educ. 2021;85(Suppl 3):1914‐1916. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shapiro MC, Anderson OR, Lal S. Assessment of a novel module for training dental students in child abuse recognition and reporting. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(8):1167‐1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tariq K, Azfar W, Saleem Z, Asghar F, Ibnerasa S. Effectiveness of virtual small group discussion: a qualitative study of dental student's perception. Rawal Med J. 2023;48(2):497‐500. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tee WX, Tan SH, Marican F, Sidhu P, Yerebairapura Math S, Gopinath D. Comparison of digital interactive case‐based educational resource with virtual role play in dental undergraduates in clinical oral medicine/oral pathology education. Healthcare. 2022;10(9):1767. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thor D, Xiao N, Zheng M, Ma R, Yu XX. An interactive online approach to small‐group student presentations and discussions. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41(4):498‐504. doi: 10.1152/advan.00019.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ullah R, Siddiqui F, Adnan S, Afzal AS, Sohail Zafar M. Assessment of blended learning for teaching dental anatomy to dentistry students. J Dent Educ. 2021;85(7):1301‐1308. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Veeraiyan DN, Varghese SS, Rajasekar A, et al. Comparison of interactive teaching in online and offline platforms among dental undergraduates. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yu‐Fong Chang J, Wang LH, Lin TC, Cheng FC, Chiang CP. Comparison of learning effectiveness between physical classroom and online learning for dental education during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Dent Sci. 2021;16(4):1281‐1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang W, Li ZR, Li Z. WeChat as a platform for problem‐based learning in a dental practical clerkship: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12127. doi: 10.2196/12127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zheng M, Bender D, Reid L, Milani J. An interactive online approach to teaching evidence‐based dentistry with web 2.0 technology. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(8):995‐1003. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moazami F, Bahrampour E, Azar MR, Jahedi F, Moattari M. Comparing two methods of education (virtual versus traditional) on learning of Iranian dental students: a post‐test only design study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Soltanimehr E, Bahrampour E, Imani MM, Rahimi F, Almasi B, Moattari M. Effect of virtual versus traditional education on theoretical knowledge and reporting skills of dental students in radiographic interpretation of bony lesions of the jaw. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1649-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kogan JR, Shea JA. Course evaluation in medical education. Teach Teach Educ. 2007;23(3):251‐264. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative methods in health research. Qualitative Research in Health Care. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006:1‐11. doi: 10.1002/9780470750841.ch1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lo CK, Hew KF. Design principles for fully online flipped learning in health professions education: a systematic review of research during the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):720. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03782-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Donkin R, Yule H, Fyfe T. Online case‐based learning in medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):1‐12. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04520-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuwaiti AA. Health science students’ evaluation of courses and instructors: the effect of response rate and class size interaction. Int J Health Sci. 2015;9(1):51‐60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dolenc K, Sorgo A, Ploj Virtič M. The difference in views of educators and students on forced online distance education can lead to unintentional side effects. Educ Inf Technol. 2021;26:7079‐7105. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10558-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Erdilek D, Gümüştaş B. Güray Efes B. Digitalization era of dental education: a systematic review. Dent Med Probl. 2023;60(3):513‐525. doi: 10.17219/dmp/156804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dong H, Guo C, Zhou L, et al. Effectiveness of case‐based learning in Chinese dental education: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e048497. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thistlethwaite JE, Davies D, Ekeocha S, et al. The effectiveness of case‐based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: bEME Guide No. 23. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):e421‐e444. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.680939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bassir SH, Sadr‐Eshkevari P, Amirikhorheh S, Karimbux NY. Problem‐based learning in dental education: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(1):98‐109. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2014.78.1.tb05661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gianoni‐Capenakas S, Lagravere M, Pacheco‐Pereira C, Yacyshyn J. Effectiveness and perceptions of flipped learning model in dental education: a systematic review. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(8):935‐945. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Otto S, Bertel LB, Lyngdorf NER, Markman AO, Andersen T, Ryberg T. Emerging digital practices supporting student‐centered learning environments in higher education: a review of literature and lessons learned from the Covid‐19 pandemic. Educ Inf Technol. 2024;29(2):1673‐1696. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11789-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S. Method and reporting quality in health professions education research: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45(3):227‐238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Webster F, Krueger P, MacDonald H, et al. A scoping review of medical education research in family medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0350-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Crotty MJ. The Foundations of Social Research : Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process . Sage Publication; 1998:1‐256.

- 66. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334‐340. doi:https://10.1002/1098‐240X(200008)23:4<334::AID‐NUR9>3.0.CO;2‐G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O'Flynn‐Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods. 2004;3(1):1‐11. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Horn C, Snyder BP, Coverdale JH, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Educational research questions and study design. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):261‐267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]