Abstract

Glaucoma, a visual thief, is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and the loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Selecting suitable animals for preclinical models is of great significance in research on the prevention, early screening, and effective treatments of glaucoma. Rabbit eyeballs possess similar vascularity and aqueous humor outflow pathways to those of humans. Thus, they are among the earliest in vivo models used in glaucoma research. Over the years, rabbit models have made substantial contributions to understanding glaucomatous pathophysiology, surgical adaptations, biomedical device development, and drug development for reducing IOP, protecting RGCs, and inhibiting fibrosis. Compared to other animals, rabbits fit better with surgical operations and cost less. This review summarizes the merits and demerits of different ways to produce glaucomatous rabbit models, such as intracameral injection, vortex vein obstruction, Trendelenburg position, laser photo‐coagulation, glucocorticoid induction, limbal buckling induction, retinal ischemia–reperfusion models, and spontaneous models. We analyzed their mechanisms in the hope of providing more references for experimental design and promoting the understanding of glaucoma treatment strategies.

Keywords: aqueous humor outflow, glaucoma, intraocular pressure, rabbit eye anatomy, retinal ischemia–reperfusion

Glaucoma, a visual thief, is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Selecting suitable animals for preclinical models is of great significance in research on the prevention, early screening, and effective treatments of glaucoma. Rabbit eyeballs possess similar vascularity and aqueous humor outflow pathways to those of humans. Thus, they are among the earliest in vivo models used in glaucoma research. Over the years, rabbit models have made substantial contributions to the understanding of glaucomatous pathophysiology, surgical adaptations, biomedical device development, and drug development for reducing IOP, protecting RGCs, and inhibiting fibrosis. Compared with other animals, they fit better with surgical operations and cost less. This review summarizes the merits and demerits of different ways to produce glaucomatous rabbit models, such as intracameral injection, vortex vein obstruction, Trendelenburg position, laser photo‐coagulation, glucocorticoid induction, limbal buckling induction, retinal ischemia–reperfusion models, and spontaneous models. We analyzed their mechanisms in the hope of providing more references for experimental design and promoting the understanding of glaucoma treatment strategies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases characterized by optic nerve head cupping, optic nerve atrophy, and visual field defects, which can progressively lead to irreversible visual impairment and ultimate blindness. High intraocular pressure (IOP) emerges as the primary risk factor. 1 According to a report, the number of global glaucoma patients is projected to surpass 112 million by 2040, representing a key population highly susceptible to vision loss. 2 The disease burden is severe, and animal models serve as fundamental tools for studying how to relieve this. To delve into the pathogenesis of glaucoma and develop safer and more effective disease‐modifying therapies, it is crucial to establish a physiologically relevant model that can accurately replicate and assess the in vivo changes experienced by patients. Monkeys, mice, rats, and rabbits are the most commonly used ones.

In general, monkeys are ideal options, whose anatomical characteristics are similar to those of humans, as are their behaviors and metabolism. But the economic and ethical factors limit their application; mice and rats are inexpensive and easy to house. Besides, the transgenosis technique allows them to be customized in accordance with experimental needs. However, the small size of their eyeballs is inconvenient for surgical operations and observation. Thus, rabbits provide an excellent compromise between monkeys and rats. As one of the earliest animals applied in glaucoma research, they are docile and have larger eyeballs, which is conducive to the implantation of drugs or materials. Meanwhile, the distribution and morphology of their ocular vessels are generally consistent with those in humans, as is the aqueous humor outflow (AHO) pathway. 3 , 4 The comparable average AHO rate and volume grant them superiority in terms of pharmacokinetic studies of anterior segment drug delivery. 5 In addition, their subconjunctival tissues exhibit a strong and rapid inflammatory and fibrosis response to foreign matters. 6 Therefore, over the years, rabbit models have made significant contributions to understanding glaucomatous pathophysiology, surgical adaptations, biomedical device development, and drug delivery for reducing IOP, protecting retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), and inhibiting fibrosis.

This review systematically discusses and summarizes the merits and demerits of different glaucoma rabbit models. We analyzed the mechanisms in the hope of providing more references for experimental design and promoting a better understanding of glaucoma prevention and treatment strategies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Common inducible glaucoma rabbit models.

2. INDUCIBLE GLAUCOMA RABBIT MODELS

Dysfunction of aqueous humor (AH) circulation can elevate IOP and cause glaucoma. Nowadays, it is widely recognized that AH mainly drains through two pathways (Figure 2): a conventional pathway where fluid secreted by the ciliary epithelium enters the anterior chamber (AC) through the pupil, passes through the trabecular meshwork (TM) and Schlemm's canal (SC), and is ultimately drained into the intrascleral venous plexus via collector channels or the episcleral venous plexus via aqueous veins. 7 Additionally, there is an unconventional pathway where AH flows into the ciliary body from AC along the baric gradient, draining across the ciliary intermuscular space to the suprachoroidal space and the sclera, or discharging into the vortex veins. 8 Consequently, the currently common modeling methods mostly involve blocking the iridocorneal angle, sclerosing the TM, increasing the pressure of the episcleral veins, and ligating the vortex veins, all of which aim at reducing aqueous outflow and increasing the resistance.

FIGURE 2.

Different pathways of aqueous humor (AH) draining. AC, anterior chamber; SC, Schlemm's canal; TM, trabecular meshwork.

2.1. Intracameral injection

Injecting a specific substance into AC, like carbomer, methylcellulose, chondroitin sulfate, α‐chymotrypsin, ghost cells, and streptovirudin, to bring about chronic ocular hypertension (OHT) in rabbits is the most widely used approach. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Generally, a rabbit with a stable IOP of over 22 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa) is considered a successful model. 12 Given that ghost cells will cause poor fundus visibility and low stability of OHT produced, 9 , 10 and streptovirudin has certain limitations in practice, 11 we only summarize the applications of some viscous substances and α‐chymotrypsin as follows:

2.1.1. Viscous substances

Carbomer is a high polymer with excellent thickening and viscosity properties. It can modify the interaction forces between charges to achieve gelation as the pH value changes. Current research indicates that carbomer exhibits its maximum viscosity within the pH range of 6 to 12. 14 Significantly, the AH has a pH value ranging from 7.3 to 7.5, which is adequate to meet the gelatinous requirements for molecular chain stretching and entwining. Injection of carbomer can definitely thicken the AH, making it tough to circulate.

In Lanzi's team, to evaluate the IOP‐lowering effects of histamine H3 receptor antagonists, OHT rabbits were produced by repeated intracameral injections of 0.25% carbomer, once a day, 0.1 mL each time for two consecutive days. 13 The mean IOP finally increased to 38.3 ± 1 mmHg and was maintained for 2 weeks after modeling. 13 Moreover, Xu Yan et al. successfully established OHT rabbits by intracameral injections of compound carbomer, a mixed solution containing 3 g/L carbomer and 0.25 g/L dexamethasone. 12 It was found that under the influence of compound carbomer, the high IOP was more long‐lasting (20–50 days), which was better than the traditional carbomer‐based scheme. Furthermore, even if the IOP dropped below 20 mmHg midway, a re‐injection would be useful to raise it for another 1 month. Meanwhile, its slow and sustained IOP‐rising effect could hardly result in eye inflammations and avoid a possible keratectasia caused by a sharp elevation in pressure. This method was conducive to reducing adverse effects on the posterior pole and improving the precision of IOP measurements. 12 In addition, in 2009, Wang Yuan‐yuan proposed a possible optimization: injecting the viscous substances at the edge of the pupil instead of the peripheral iridocorneal angle. 15 According to their research, the latter mode still had the problem of too short the gel time and too fast an increase in IOP, which could result in acute perilimbal rupture. Nevertheless, there was a low probability of rupture or lens dislocation in eyes with injections near the pupil. When the AH in the posterior chamber flowed through the pupil, it continuously scoured the compound carbome injected right there, preventing it from forming gel or thickening too quickly, while also accelerating drug diffusion. A single injection could smoothly increase IOP to 29.2 ± 5.4 mmHg for more than 50 days, gradually causing glaucomatous damage such as optic nerve head cupping and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning. 15

Other viscous substances, such as 1% methylcellulose and 20% chondroitin sulfate, can produce similar effects as well. 16 The classical method is well accepted in chronic OHT rabbit modeling, characterized by easy operation, relatively low cost, stable IOP, and independent reproducibility, as well as few complications. It plays an important role in the study of the nature and pathogenesis of glaucoma, glaucomatous drugs and surgical treatment, and even the post‐operative anti‐scarring treatment today.

2.1.2. α‐Chymotrypsin

α‐Chymotrypsin is one of the serine peptidases. According to reports, the lens zonule will be enzymatically broken down at the initial stage when α‐chymotrypsin is injected into AC. 17 , 18 , 19 The decomposed tissue fragments gradually accumulate in the TM, directly impeding the AH outflow facility. On the flip side, this enzyme can irreversibly damage the blood‐aqueous barrier, leading to an increase in proteins and inflammatory corpuscles in AH and increasing aqueous inflow. 17 , 18 , 19 It is within this dual changing environment that the IOP rapidly climbs to a higher level. As to Melena's research, an intracameral injection of 60 units of α‐chymotrypsin dissolved in 0.2 mL of saline could successfully elevate albino rabbits' IOP to 1.5 times the normal IOP 17 ; Angel Aillegas's team verified that an intracameral injection of 3 mg/mL of α‐chymotrypsin could ultimately maintain the IOP at a level of more than 25 mmHg during a 40‐day follow‐up 20 ; Kalvin et al. compared the effects of α‐chymotrypsin at four different injection sites, respectively: the anterior chamber, posterior chamber, anterior vitreous, and posterior vitreous. 18 They found that if the drug was administrated in the posterior chamber, the success rate of glaucoma models could be optimized to 100%; Lee et al. found significant thinning of the retinal ganglion cells and inner nuclear layers in α‐chymotrypsin‐induced rabbits. 21 Therefore, they believed it was a highly reproducible formula that worked well in practice because of the rapid increase and persistence of high IOP in rabbits. However, there were also dissenting voices. Lu et al. suggested that α‐chymotrypsin could result in severe entophthalmia and lens dislocation. 10 The experimental results of Zhu's team also demonstrated that although intracameral injection of 0.5% α‐chymotrypsin could successfully produce a pronounced IOP elevation lasting for about 1 month, the odds of keratectasia, corneal perforation, lens opacity, and retinal hemorrhage were not low. 16 This could be attributed to the breakdown of blood‐aqueous barrier as we mentioned previously. Besides increasing the IOP, the compositional changes in AH affected the metabolism of the corneal endothelium and crystalline lens. Meanwhile, the increased diffusion of inflammatory mediators in the eye could influence the permeability of retinal blood vessels, leading to hemorrhage. In fact, these unexpected lesions seriously affect the accuracy of IOP measurement and disturb the observation of the anterior segment and fundus of the eyes. For this reason, in contrast to the widespread use of viscous substances, the intervention with α‐chymotrypsin in the anterior chamber seems to have gradually become obsolete in modern glaucoma studies.

2.2. Vortex vein obstruction

The vortex veins are responsible for recycling the blood from a portion of the iris, ciliary body, and all of the choroid, sending it into the blood circulation. Interestingly, in 1962 Bill discovered that these veins also participate in the unconventional pathway. 22 Many research studies suggested that the uveovortex outflow could explain 8–10% AHO in non‐primates. 23 , 24 Despite the fact that specific data varied between experiments, they were related to many factors such as the IOP at that time, the tension of the ciliary ligament, and the choice of tracers. As research has progressed, different voices are all echoing the same fact. That is, the AH in the unconventional pathway enters the epichoroidal space through the ciliary muscle. Here, it takes two routes: one goes through the uveoscleral pathway, passes through the sclera, and returns to the systemic circulation; the other enters the vortex veins and flows back to the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins. 25 , 26 Obstruction of vortex veins will augment the resistance of AHO. In the meantime, increased venous pressure can prompt vasocongestion as well as swelling of the tunicae uveae. The AC narrows down and even closes up, giving rise to pathological changes similar to glaucoma. 27

In 1992, Zhu et al. reported that chronic OHT in rabbits could be produced by ligaturing three of the vortex veins in the superior nasal, superotemporal, and infratemporal sides. 16 After modeling, the IOP steadily increased to an average of about 27 mmHg and lasted for about half a month. Based on their judgment, a higher IOP might be achieved by occluding more vortex veins 16 ; Xie Zheng‐Gao et al. randomly divided the rabbits into four groups, cauterized 1–4 vortex veins in each group, respectively, and found the most significant elevation, a sharp increase in IOP to 65 mmHg with optic nerve injury, occurred in rabbits that had undergone simultaneous occlusion of the superior nasal, inferior nasal, superotemporal, and infratemporal vortex veins. 28 According to their observations, the remaining two untreated veins in rabbits could serve a compensatory function, allowing the elevated IOP to slowly move down within 48 h, without significant complications. Therefore, unlike Zhu et al., Zheng‐Gao et al. held that this method was more suitable for establishing acute OHT, rather than chronic models. 28 Currently, despite ongoing debate about the steadiness of the OHT induced by vortex vein intervention, there is no doubt that it can indeed induce elevated IOP. This method is relatively easy to perform and has a high success rate, which is commonly applied in studies examining the pathological mechanisms of glaucomatous optic nerve damage and the development of therapeutic drugs. However, excessive ligation can still cause problems such as anterior chamber exudation and retinal hemorrhage. 16 In addition, the manipulation of opening the conjunctiva will affect the subconjunctival environment in rabbit eyes, thereby limiting its application in anti‐scarring experiments after glaucoma filtering surgery (GFS).

2.3. Trendelenburg position

Trendelenburg position was implemented to induce acute OHT in New Zealand white rabbits in Zhang Yao's team, investigating the IOP‐lowering effect of Neu‐P11. The experimental rabbits were kept supine with their heads down at an angle of 80° from 8:00 to 9:00 a.m., during which time the IOP was measured every 5 min and significantly elevated to 1.9 times baseline eventually. 29 The same method can also be applied to establish acute OHT models in rats. 30 Regarding this, it might have referred to an opinion by R. N. Weinreb's team in 2003 to elevate the IOP with the head‐down‐and‐feet‐up position. 31 The episcleral venous pressure (EVP) and IOP can keep increasing as the head is lowered to a greater extent. According to the modified Goldmann equation: IOP = [(Fac − Fu) ÷ C] + EVP, IOP is positively correlated with EVP. 32 In this equation, Fac stands for the aqueous humor inflow, Fu for the unconventional aqueous humor outflow, and C‐value for the coefficient of outflow facility. By altering the position, there was an elevation in both the orbital and episcleral venous pressures, which subsequently offset the pressure gradient between the AC and the SC. Besides, it led to uveal vasocongestion and uveal swelling, narrowing the iridocorneal angle. 33 , 34 These changes, thus, diminished the aqueous outflow and provoked a rapid increase in IOP. The degree of steep Trendelenburg position is closely related to ischemia retinae and optic nerve degeneration. 33 , 34 This method is simple, non‐invasive, without anesthesia, and has almost no cost. Nevertheless, there have been no reports of other laboratories reproducing it so far. Apart from IOP changes, the success rate, requisite intervention frequency, specific ocular pathology, and so on remain to be further studied.

2.4. Laser photo‐coagulation

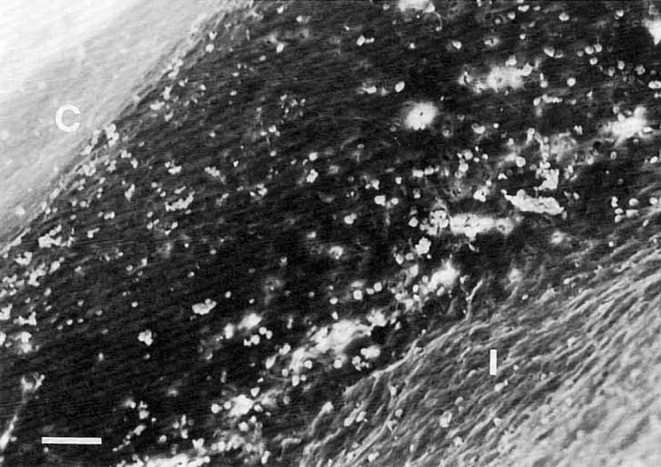

As first described by March et al. in 1984, argon lasers can successfully induce open‐angle glaucoma in adult New Zealand rabbits by inflicting sclerotic damage to the TM. 35 The pigmented TM was operated with 50 μm laser spots, 0.1–0.5 s duration, and a power intensity of 0.6–1.0 W. The AHO was instantly blocked. Finally, the average IOP was higher than 30 mmHg, accompanied by optic nerve cupping and buphthalmus. It was observed in their experimental results of the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) that the TM lost its normal reticulate structure in the laser‐induced models, replaced by the fibrous tissues (Figures 3 and 4). Correspondingly, the light microscopy revealed massive accumulation of carbon particles in the TM, suggesting the failed drainage of carbon suspension injected in advance; In addition, this approach was replicated in pigment rabbits by Gherezghiher et al. who further quantified the outflow facility afterwards. According to their report, the inter‐trabecular space closed when impacted by the laser, healing in a manner of scar formation and then reducing the outflow by 60%. 36 Typical changes in glaucoma such as optic nerve cupping, optic atrophy, and loss of axons were simultaneously discovered along with high IOP in the operated rabbits; Kim et al. operated on the rabbits using a diode laser with a parameter setting to a 75 μm spot size, a 0.1‐s duration, and a power intensity of 1.0 W, to produce chronic glaucoma rabbits and assess the IOP‐lowering effect of the HL3501. 37 The OHT was consistently higher than 35 mmHg eventually. Indeed, in recent decades, these versions of laser‐induced models have been widely accredited between laboratories, with the advantages of rapid, stable, and long‐lasting effects, as well as their typical glaucoma pathological changes. At the same time, the wider iridocorneal angle in rabbits can make up for the narrow space in rodents' eyeballs, which are peculiarly prone to poor operation, unintended inflammatory reactions, and a high failure rate. However, as a non‐invasive intervention, laser photo‐coagulation relies on expensive laser equipment and the exquisite technology of operators. The cost is relatively high, making it challenging to frequently apply in large sample studies.

FIGURE 3.

Trabecular meshwork™ in healthy rabbits (figure courtesy—Lasers in Surgery and Medicine). 35

FIGURE 4.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) appearance of the trabecular meshwork (TM) in rabbits after laser (figure courtesy—Lasers in Surgery and Medicine). 35 Bar equals 50 μm; C, Cornea; I, Iris. Pictures are reprinted with the permission of the press.

2.5. Glucocorticoid induction

Glucocorticoids (GC), such as dexamethasone, betamethasone, fluorometholone, triamcinolone acetonide (TA), have gradually played an important role in the study of open‐angle glaucoma and glucocorticoid‐induced glaucoma (GIG) since 1970, when Lorenzetti et al. first declared that the topical application of GC could induce OHT rabbits. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Reportedly, a GIG model could be produced by subconjunctival injection of 0.5 mg dexamethasone sodium phosphate, once every other day for 15 times. The average IOP increased to 28.8 ± 3.0 mmHg eventually 44 ; Ticho et al. induced OHT in albino rabbits with 1% dexamethasone eye drops, thrice daily for two consecutive weeks. The IOP also significantly increased after treatment, and excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) was observed in the experimental samples. 43 In addition, Qin Yi et al. compared the effects on rabbits at the ages of 7 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year, respectively. All rabbits were induced to show an obvious elevation in IOP after topical use of 0.1% dexamethasone, four times a day for 1 month. The youngest rabbits showed superiority over adult ones and had the highest IOP, which did not return to baseline until the 7th week 40 ; Zhao Jing's team adopted a method of combining eye drop treatment with subconjunctival injection. Compared to monotherapy, a concurrent use of 0.5% dexamethasone sodium phosphate (thrice a day) alongside a weekly injection of 3 mg TA for 8 weeks could produce a more stable and long‐lasting high IOP. 42 Currently, it is believed that GC can inhibit the activity of hyaluronidase, resulting in the accumulation of glycosaminoglycan (GAG). The unhydrolyzed GAG and the ECM materials pile up together within the trabecular beams and within the juxtacanalicular tissue (JCT), blocking the outflow pathways. 45 At the same time, the TM tissues are hardened by the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton under the influence of GC, impairing the phagocytic function of endothelial cells, which further obstructs the AHO. 45 The elevated IOP arising therefrom can gradually return to the normal level with GC withdrawal, but the wave amplitudes of photopic negative response (PhNR) and visual evoked potential (VEP) remain lower, suggesting RNFL impairment and permanent loss of RGCs. 41 This modeling plan is simple and reproducible, with great potential, which is the preferred option for GIG studies. However, certain studies have indicated that the continuous use of GC may disrupt the corneal barrier, increase the risk of infection, 46 or lead to scleral thinning. 47 Moreover, glucocorticoids tend to affect the metabolism of lens fibers and induce the accumulation of water and proteins, resulting in cataracts. 48 These complications remain issues that need to be considered.

2.6. Unilateral limbal buckling

In a 2019 report, Wang et al. proposed that fundus alterations induced by α‐chymotrypsin or laser photo‐coagulation in glaucomatous rabbits might be involved in inflammation, rather than the simple mechanical pressure. For this reason, they performed a unilateral limbal buckling surgery on rabbits to establish another typical chronic glaucoma model. 49 The process began with a circular incision of the bulbar conjunctiva. Then, they had to sew up a 3‐mm‐wide annular latex belt near the corneal limbus, right through the in‐sclera tunnel and the rectus. They made sure that the tension of the latex belt was uniformly distributed, extracted around 120 μL of aqueous humor, and eventually closed the conjunctiva. The entire operation took about 1.5 h. After modeling, the anterior chamber angle would close down and adhesion due to the pressing from the sutured belt. Meanwhile, the IOP was immediately elevated, and the elevated level was maintained for more than a month. To avoid excessive pressure that could induce inflammation or other complications, Wang et al. used an elastic latex belt, allowing for the AC to be partially reopened in accordance with the IOP, ensuring that the peak IOP value remained consistently below 45 mmHg. 49 , 50 Eight weeks later, even after the implant was removed, the optic neuropathy caused by mechanical pressure, such as the cupping optic nerve, enlarged cup/disc ratio, and RGCs loss, was irreversible. 49 , 50 Moreover, the induced RGC loss exhibited a sectorial distribution, with the apex oriented toward the ONH, which closely resembled the thinning of the RNFL observed in glaucomatous patients, thus indicating the potential to simulate the optic nerve degenerative damage caused by chronic glaucoma (Figure 5). 50

FIGURE 5.

Optic nerve injury in glaucoma rabbits (Figure courtesy—Experimental Eye Research). 50 (A–E) Normal optic disc; (F–J) Enlarged cup/disc ratio after molding; (K–P) RGC loss after molding; (Q) Quantitative analysis showed a significant correlation between RGC decrease and optic cup depth; CSLO, Confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Pictures are reprinted with the permission of the press.

At present, this method has not been widely used due to its stringent surgical demands, but its cost of instruments and equipment is low, and the tools are simple and easy to obtain. In addition, Wang's study proved that it can achieve reproducibility and a higher success rate than laser‐induced models. The IOP increased smoothly, and the difference between rabbits was less, which avoided corneal enlargement and inflammation as much as possible. 49 , 50 In the future, by refining surgical steps and enhancing modeling efficiency, unilateral limbal buckling could become a highly promising choice for producing chronic glaucoma rabbits.

2.7. Retinal ischemia–reperfusion models

2.7.1. Intracameral perfusion

The vascular ischemia theory is another widely acknowledged pathogenesis of glaucoma in addition to the mechanical theory. Many factors, for example, a sharp and severe IOP increase, can cut down the blood perfusion of the optic disc, leading to an insufficient supply of oxygen and glucose in the fundus. Retinal ischemia‐hypoxia causes mitochondrial dysfunction, triggering a cascade reaction that ultimately ends with axonal degeneration and RGC apoptosis. 51 Most notably, the injury continues in the reperfusion process. As the restoration of blood supply, a great quantity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is produced and the inflammatory responses are activated, leading to biomolecule damage and tissue destruction again. 51 Based on this, retinal ischemia–reperfusion (RIR) models have been common alternatives for researching glaucoma, especially glaucomatous optic nerve damage in laboratories.

Constantly infusing physiological saline into AC is the most classical way. Connect a dropping bottle filled with sterile saline and the AC of rabbit by a disposable infusion set. When soaring mechanical pressure gives rise to ischemia, the needle attached will be removed to induce a RIR model. Zhang Yong‐li's team found that there was an increasing pressure up to 125.25 mmHg when the dropping bottle was 170 cm vertically away from the AC. The iris and retina turned pale immediately, and severe impairments of the retinal morphology and function were observed after 60 min. 52 Ge et al. also maintained the pressure at about 120 mmHg and observed ischemia in fundus 45 min later. 53 The wave ampltiudes on the electroretinogram (ERG) disappeared both in the periods of ischemic and reperfusion; Kun‐ya et al. ingeniously added a glass tube loaded with mercury to the traditional perfusion tube. They connected the rabbit's AC, a sensor, and a dropping bottle that was at 50 cm high with a Y‐shaped infusion set to quantify the inflow of the eyeball and calculate the appropriate model‐making time. 54 According to the experimental data, the rabbits' IOP was equal to the pressure exerted when the infusion had been conducted for 282.93 ± 42.68 min, which was considered to be another modeling criterion besides the traditional standard of the iris and retina turning pale. 54 Actually, so far no final conclusion has been reached on the optimal infusion time, the best dropping bottle height, and so on for RIR rabbits. But the close relationship between the ocular perfusion pressure (OPP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and IOP can be reasoned with. From the analysis of the formula 55 : OPP = MAP – IOP – 14, once the IOP approaches the level of MAP, the overwhelming majority of blood supply in the retinal capillaries can be interrupted, and the branches of the arteria ciliares will also be severely affected. As is known, the maximum systolic blood pressure (SBP) of purebred white big‐ear rabbits ranges from 100 to 300 mmHg, 52 whereas the MAP is undoubtedly less than the SBP. In theory, the hydrostatic pressure hovering around 120 mmHg set up by many laboratories can completely block the retinal blood flow and achieve RIR. The method is simple, relatively mature, and reproducible. But there is a possibility of the needle slipping and leakage. Meanwhile, the mechanical pressure generated by perfusion may increase the shear stress on the blood vessel walls, which changes the tight junctions between vascular endothelial cells and disrupt the blood‐aqueous barrier. Consequently, it brings a higher risk of inflammation and bleeding, affecting experimental observations.

2.7.2. Other inducible models

Essentially, intracameral perfusion is merely one of the methods, and high IOP is a cause that is not irreplaceable, whereas fundus changes are the key focus. RIR rabbits produced by intracameral perfusion belong to the non‐IOP‐dependent models. Therefore, Okuno et al. examined glutamate (Glu) in these rabbits' optic nerve head (ONH) and paid attention to retinal excitotoxicity. 56 Their results showed that with the IOP intervention, the ONH turned pale and Glu significantly increased. Even if blood flow recovered, Glu was still at an obviously high level, the ONH axon was damaged, and massive RGC loss was observed. Glu changes are strongly associated with the characteristic progression of glaucoma. Currently, it is believed that extracellular Glu always remains low in a normal physiological environment. Retinal ischemia can upset the balance, leading to a large amount of release and aggregation of Glu, which causes retinal excitotoxicity, resulting in RGC apoptosis and necrosis. Meanwhile, the extensive influx of calcium through Glu receptors can also exacerbate vasospasm, initiating a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to retinal neurodegenerative changes. 57

N‐Methyl‐d‐aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors are subtypes of Glu receptors. Dong's team established glaucoma rabbits by intravitreal injection with NMDA to study the optic neuroprotective effect of brimonidine. 58 According to their results, over‐activation of NMDA receptors caused the loss of about 40% of the neurons in the RGC layer without increasing the IOP. Besides, Staubli et al. quantified this kind of model using the scanning VEP technology. They found that both the RGC layer and RNFL became much thinner in the visual streak of rabbits' eyes after NMDA treatment. 59 The change was stable and lasting.

Some researchers opted to apply vasoconstrictors to produce glaucoma models. Kageyama et al. used an osmotically powered minipump to deliver endothelin‐1 (ET‐1) to ONH at a constant rate. The rapid and potent constriction of blood vessels led to less blood flow and higher Glu levels. Confocal scanning laser observations revealed that the rabbits had a typical cupping of optic disc and a diminished neural rim, which they believed could simulate the physiopathology of normal tension glaucoma (NTG). 60 Kim's team concurred with this assessment. They found a severe disruption of various retinal layers in rabbits treated with ET‐1. The inner nuclear layer (INL), the outer nuclear layer (ONL), and the outer molecular layer (OML) were all significantly thinner compared to the control group, and the RGC apoptosis was captured. 61 These models, which hold optic nerve damage due to microcirculatory disturbance and excitotoxicity, are of great importance to develop optic neuroprotective drugs for glaucomatous conditions. The entire operating process could be simpler, such as administering ET‐1 directly into the vitreous body or next to the ONH, without a minipump. 62 The time could be set to twice a week for a continuous month. These ensuing models also hold glaucomatous relevance and applicability. According to reports, the rabbits had extensive ischemia in the fundus too, resulting in a series of optic nerve damage and ERG changes. Data obtained by laser speckle interferometry indicated that the capillary blood flow in ONH decreased by 80%. 63 Pathological results revealed axonal loss and demyelination, and fundus examination showed an enlarged cup/disc ratio. 63 However, the existing controversy is over whether the ET‐1 has a detrimental effect on the eyes.

3. SPONTANEOUS GLAUCOMA RABBIT MODELS

Spontaneous animal models refer to a breed of disease models arising on the basis of hereditary factors or obtained through transgenic technology. It was reported in 1987 that, initially, the rabbits with hereditary glaucoma were usually albino rabbits with autosomal recessive inheritance, most of which were unhealthy and of poor reproduction. 64 To improve their hardiness, A. H. Bunt‐Milam's team bred a new type of pigmented rabbits with congenital glaucoma by animal crossbreeding, of which the IOP progressively increased to 48 mmHg within 3 months postnatally. The axonal transport at the ONH went out of action accompanied by IOP elevation, and some optic nerve terminals in the superior colliculi began to degenerate. 64 In addition, Solomon et al. pioneered an idiopathic OHT that resembled primary infantile glaucoma in 1995. 65 According to their report, the models held high IOP over 30 mmHg and large corneal diameter over 16 mm, occasionally associated with corneal opacity and neovascularization. Maldevelopment of the iridocorneal angle was the material cause of morbidity. Currently, it is believed that there are similarities between the morphology of healthy rabbit eyeballs and humans, such as the aqueous plexus corresponding to the SC, and the angular meshwork corresponding to the TM, arranged with numerous trabecular sheets. The fluid produced by the ciliary body is drained from the entrance of the angular meshwork to the aqueous plexus, flows through the aqueous veins, and then discharges into episcleral veins. 66 , 67 According to reports, this strain of inherited glaucoma rabbits had a shorter axis of the aqueous plexus. Despite their open lumen, the diameter was smaller and the whole eyeball appeared crowded. Compared to normal eyes, the arranged trabecular sheets were more compact and of less quantity in the glaucomatous rabbits, making the aqueous humor outflow difficult. Meanwhile, massive ECM deposition was captured in their trabecular tissues from SEM results. 65 From Solomon et al., the congenital differences in anatomy made it a perfect research model to assess potential strategies for glaucoma therapy.

In 2000, Sun et al. examined the effects of endoscopic goniotomy assisted with the free electron laser and traditional goniotomy by using congenital glaucoma rabbits 68 ; 21 years later, the spontaneous OHT rabbits whose IOP were around 35.8 mmHg also played an important role in in vivo research on the IOP‐lowering effect of NCX 667. 69 However, compared to the prosperity of transgenic rodent models, for example, the DBA/2 J mice resembling chronic OHT models, 70 the CLR mice resembling acute angle‐closure glaucoma models, 71 and the NF‐κBp50‐deficient mice resembling normal tension glaucoma models, 72 the transgenic rabbits of glaucoma have not made great breakthroughs yet. A 1998 study in Saudi Arabia once indicated that the CYP1B1 mutation was a critical factor in primary congenital glaucoma in humans. 73 But due to the inadequate genome sequence and the anatomic discrepancy that rabbits did not have scleral spurs or scleral furrows, the researchers failed to identify the presence of CYP1B1 mutations in the experimental rabbits. 73 Since then, studies on transgenic glaucoma rabbits have seldom been reported. Considering the low incidence and long culturing cycle of transgenic mice, and the inconvenience of performing operations on small eyeballs, it is still well worth producing glaucomatous rabbits by transgenic technology in the future. In spite of the high cost, the spontaneous models with accordant pathology in IOP and optic nerves are expected to make up for the shortcomings that the inducible rabbits are of large individual differences and insufficient stability, providing more possibilities for scientific research and clinical practice of glaucoma.

4. PERSPECTIVES AND PROSPECT

The pathogenesis of glaucoma is very complex. As a result, finding an appropriate animal model in in vivo research is the basis for correctly understanding the strategies of prevention, early screening, and long‐term therapy for glaucoma. Rabbit is one of the most widely used glaucoma models. Although there are certain differences between the anatomy of rabbits and that of humans, there is no Schlemm's canal in the rabbit eye. Moreover, the trabecular sheets are connected to the wall of eyeball only by thin collagen bundles, so the angular meshwork similar to the TM in the rabbit eye tends to separate from the eye wall with the dissection of the pectinate ligaments and iris roots. 74 But these morphological differences have almost no impact on studies of AHO. As we have discussed in the previous section (“Spontaneous glaucoma rabbit models”), the rabbit has an aqueous humor plexus that functions similarly to the SC. 66 , 67 It forms a circular passage around the iridocorneal angle. Here, the AH from the angular meshwork enters and finally returns to the systemic circulation. This is equivalent to the conventional pathway in humans. Meanwhile, there are continuous endothelial cells between their ciliary cleft and the peripheral cornea. The AH passes through the interstice within the pectinate ligaments and enters the ciliary cleft, which is essential for both the conventional and unconventional outflow pathways. 74 , 75 In the fundus, the rabbit has no lamina cribiosa. But it is worth noting that their retinal stratification and distribution positions of each layer are relatively consistent with those in humans. Researchers have found that rabbits have the potential to mimic optic nerve degeneration and axonal loss in human glaucoma. 76 Therefore, this paper presents a comprehensive overview of the current state of glaucoma rabbit models, analyzing and comparing their respective advantages and disadvantages (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Advantages and challenges of glaucomatous rabbits.

| Models | Mechanisms | Advantages | Challenges | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intracameral injection Viscous substances α‐Chymotrypsin |

Thicken AH; block AHO Block AHO; damage blood‐ aqueous barrier |

Easy operation; reproducible; long‐lasting and stable high IOP High success rate; reproducible; rapid elevated IOP |

Multiple injections; mild inflammations Complications |

|

| Vortex vein obstruction | Augment the resistance of AHO; narrow down iridocorneal angle | Reproducible; high success rate | Duration of IOP; unsuitable for anti‐scarring studies after GFS | 16, 27, 28 |

| Trendelenburg position | Augment the resistance of AHO; narrow down iridocorneal angle | Non‐invasive; low cost | Success rate and reproducibility are unknown | 29, 30 |

| Laser photo‐coagulation | TM sclerosis; block AHO | Non‐invasive; long‐lasting and rapid elevated IOP; reproducible; high success rate | High cost; accurate operation required; irreversible damage to TM | 35, 36, 37 |

| Glucocorticoid induction | Block AHO; TM sclerosis | First choice to glucocorticoid‐ induced glaucoma | Concurrent cataract and systemic side effects | 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 |

| Unilateral limbal buckling | Close down the AC | Reproducible; smoothly elevated IOP; more homo generous; less inflammation | Time‐consuming; stringent surgical demands | 49, 50 |

|

Retinal ischemia‐ reperfusion injury Intracameral perfusion Other inducible models |

RIR injury by sharp hydrostatic pressure RIR injury by vasoconstriction or excitotoxicity |

Pressure‐independent; reproducible; high success rate Pressure‐independent; reproducible |

Corneal edema; needle slipping; leakage Unknown side effects |

|

| Spontaneous glaucoma rabbits | Hereditary factors; transgenic technology | Resemble human glaucoma naturally; high application value | High cost; scanty supply; inadequate genome sequence | 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 |

Intracameral injection with viscous substances, represented by carbomer, is the most common method to induce chronic OHT in rabbits, with a very wide application in various studies related to glaucoma. The high IOP produced is stable and long‐lasting, accompanied by consistent optic nerve crush. Meanwhile, the method itself is simple, is independently reproducible, and has fewer complications. Vortex vein obstruction is involved in opening the conjunctiva to expose vessels, which may cause damage to tissues under the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule. The method is reproducible and has a high success rate, but it is not suitable for anti‐scarring experiments after GFS; Trendelenburg position is non‐invasive and cost‐effective, yet its success rate, requisite frequency of intervention, and reproducibility remain undetermined. On the other hand, laser photo‐coagulation can induce TM sclerosis and block the AHO, thus providing a rabbit model that closely resembles primary open‐angle glaucoma in humans. This approach is also non‐invasive and can lead to a rapid and sustained elevation in IOP, with a mature surgical process and a high success rate. But the high cost and the precise operation required limit its wide application; GC‐induced rabbits take priority in studies related to the pathophysiology and treatment of glucocorticoid‐induced glaucoma. Moreover, the young rabbits display more typical glaucoma characteristics than older rabbits. But the concurrent cataract and potential systemic side effects may interfere with the experimental observations. Different from the above, the methods for producing RIR rabbits and other non‐IOP‐dependent models, such as intraocular injection with ET‐1, tend to cause characteristic fundus lesions. The thinner RNFL, enlarged cup/disc ratio, and RGC apoptosis in rabbits create conditions for researching NTG, and are of great significance for studying axonal transport, optic neuroprotection mechanisms, and therapies. But there is still some controversy about the corneal edema caused by operation and the possible ocular toxicity caused by drugs.

Despite the diversity of inducible rabbit models, the majority of interventions focus on IOP increases. Programs designed to target optic nerve damage, however, remain relatively monotonous and lack a unified standard for successful modeling, leading to ongoing debates. Most of them can only unilaterally replicate one or more of the characteristic changes of glaucoma, yet cannot fully imitate the mechanism. In addition, spontaneous glaucoma rabbits with iridocorneal angle maldevelopment possess a significant value for application purposes. But they are of incomplete DNA microarray. The progression of transgenic glaucoma rabbits also hits a bottleneck. In contrast, the rapidly developing gene‐editing mice can be an alternative, which has advantages in studying the pathogenesis and genetics mechanism of glaucoma. But they do not perform as well as rabbits in the research of glaucoma drug delivery, such as during intraocular injection of neuroprotective hydrogels and the application of IOP‐lowering micelles‐laden contact lens. When studying the implanted materials and anti‐scarring solutions for glaucoma surgery, the Tenon's capsule of mice is also more difficult to evaluate quantitatively, whereas rabbit eyes are more easily manageable in terms of fibrosis degree, efficacy, safety, and rejection reactions. 77

As a common challenge with in vivo models, there exists heterogeneity among the RGCs of different animals, which results in varied responses to glaucoma injury. 78 Currently, available retinal organoids (ROs) are one of the mainstream options that can naturally mimic the degeneration and loss of RGCs. Researchers induce the pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) from glaucoma patients to differentiate into RGCs and then develop homogeneous in vitro models with characteristics such as short axons and immature electrophysiology. 79 It provides relatively ideal conditions for exploring disease genetics and targeted therapies. Unfortunately, it is costly and has low efficiency. The cultivation of ROs is time‐consuming and of insufficient output, making it unsuitable for large‐scale experiments. Meanwhile, the in vitro RGCs can be tested only in isolation, failing to reflect the diverse cellular changes or predict potential in vivo responses that may arise from interventions. 80 Therefore, it is still necessary to continue to improve the gene pool and develop transgenic glaucoma rabbits through modern gene‐targeting and gene‐editing techniques in the future. Rabbits hold great promise on issues in providing an in vivo preclinical platform for glaucoma.

In conclusion, different models have their own distinguishing features and corresponding scopes of application. A detailed and deep understanding of their mechanisms is an essential tool for researchers to design experiments and gain experience. Scientifically selecting glaucomatous rabbit models based on specific objectives, and generating more of them that can mimic changes in humans as closely as possible, remains a key point for future ophthalmic research and clinical treatment. We hope that they can make significant contributions to the advancement of IOP‐lowering treatments, neuroprotective strategies, surgical techniques, and the development of surgical equipment. Also, we wish this in‐depth discussion could bridge the gap in researchers' comprehension of rabbits, thereby facilitating better practices.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Rong Hu: Conceptualization; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Kai Wu: Data curation. Jian Shi: Investigation. Juan Yu: Supervision. Xiao‐lei Yao: Supervision.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Study on the mechanism of protective effect of Qingguang'an on RGCs based on mitophagy, no.: 81860870); The "Wang Heng‐xin Scientific Research Fund" project of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (2023HX007); The 64th batch of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M640754).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to the Lasers in Surgery and Medicine for providing Figures 3 and 4. Thanks to the Experimental Eye Research for providing Figure 5.

Hu R, Wu K, Shi J, Yu J, Yao X‐l. Glaucoma animal models in rabbits: State of the art and perspectives—A review. Anim Models Exp Med. 2025;8:429‐440. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12565

REFERENCES

- 1. Jayaram H, Kolko M, Friedman DS, Gazzard G. Glaucoma: Now and beyond. Lancet. 2023;402:1788‐1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR, Bron AM, Ritch R, Panda‐Jonas S. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2017;390:2183‐2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shuo SONG, Yongz MENG, Hua LI. Application of glaucoma animal model in glaucoma study. Nat Sci. 2021;41(12):1850‐1855. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang L, Cui Q‐q, Zhang Y‐k, et al. Three‐dimensional reconstruction of rabbit eye vessels based on X‐ray phase contrast. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;29(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weir AB, Collins M. Assessing ocular toxicology in laboratory animals || comparative ocular anatomy in commonly used laboratory animals. Mol Integr Toxicol. 2013;1:1‐21. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asrory VDO, Sitompul R, Artini W, Estuningsih S, Noviana D, Morgan WH. The inflammatory and foreign body reaction of polymethyl methacrylate glaucoma drainage device in the rabbit eye. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(3):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewczuk K, Jabłońska J, Konopińska J, Mariak Z, Rękas M. Schlemm's canal: the outflow ‘vessel’. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100(4):e881‐e890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costagliola C, dell'Omo R, Agnifili L, et al. How many aqueous humor outflow pathways are there? Surv Ophthalmol. 2020;65(2):144‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quigley HA, Addicks EM. Chronic experimental glaucoma in primates. I. Production of elevated intraocular pressure by anterior chamber injection of autologous ghost red blood cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19(2):126‐136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu DW, Chen YH, Chang CJ, Chiang CH, Yao HY. Nitric oxide levels in the aqueous humor vary in different ocular hypertension experimental models. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2014;30(12):593‐598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wei H‐l, Liu S‐r, Liu S‐r. Establishment of chronic glaucoma rabbit model by injecting tunicamycin to anterior chamber. Yan Ke Xin Jin Zhan. 2015;35(7):629‐633. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yan X, Chen Z‐j, Song J‐z. A study of experimental carbomer glaucoma and other experimental glaucoma in rabbits. Zhong Hua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2002;3:172‐175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lanzi C, Lucarini L, Durante M, et al. Role of histamine H3 receptor antagonists on intraocular pressure reduction in rabbit models of transient ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4):981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y‐y, Li‐na D, Jin Y‐g. Application of environmentally sensitive hydrogels in drug delivery. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2021;5:1314‐1331. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y‐y, Wang W‐h. Experimental study ofcarbomer glaucoma model in rabbits by injecting different location in anterior chamber. Zhong Guo Shi Yong Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2009;05:542‐545. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu MD, Cai FY. Development of experimental chronic intraocular hypertension in the rabbit. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1992;20(3):225‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melena J, Santafé J, Segarra‐Doménech J, et al. Aqueous humor dynamics in alpha‐chymotrypsin‐induced ocular hypertensive rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999;15(1):19‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kalvin NH, Hamasaki DI, Gass JD. Experimental glaucoma in monkeys. I. Relationship between intraocular pressure and cupping of the optic disc and cavernous atrophy of the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76(1):82‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stagni E, Privitera MG, Bucolo C, Leggio GM, Motterlini R, Drago F. A water‐soluble carbon monoxide‐ releasing molecule (CORM‐3) lowers intraocular pressure in rabbits. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(2):254‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Angel Aillegas N, Tártara LI, Caballero G, Campana V, Allemandi DA, Palma SD. Antioxidant status in rabbit aqueous humor after instillation of ascorbyl laurate‐based nanostructures. Pharmacol Rep. 2019;71(5):794‐797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee C, Li Y, Huang C, Lai J. Poly (ε‐caprolactone) nanocapsule carriers with sustained drug release: single dose for long‐term glaucoma treatment. Nanoscale. 2017;9(32):11754‐11764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bill A. The aqueous humor drainage mechanism in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca irus) with evidence for unconventional routes. Invest Ophthalmol. 1965;4:911‐919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pederson JE, Gaasterland DE, MacLellan HM et al. Uveoscleral aqueous outflow in the rhesus monkey: importance of uveal reabsorption. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:1008‐1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McMaster PRB, Macri FJ. Secondary aqueous humor outflow pathways in the rabbit, cat, and monkey. Archiv Ophthamol. 1968;79:297‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jonas JB, Jonas RA, Jonas SB, Panda‐Jonas S. Ciliary body size in chronic angle‐closure glaucoma. Sci Rep‐UK. 2023;13(1):16914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson M, McLaren JW, Overby DR. Unconventional aqueous humor outflow: a review. Exp Eye Res. 2017;158:94‐111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arciniegas A, Ramirez F. Aqueous‐vortex derivation: a preliminary study on rabbits. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(9):802‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie Z‐g, Guan H‐j, Sun J‐q, et al. Acute ocular hypertension of rabbits induced by cauterizing vortex veins. Yan Ke Xin Jin Zhan. 2006;26(4):276‐279. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Y, Peng W, Yin W‐d, et al. Effects of neu‐P11 on intraocular pressure in acute high intraocular pressure rabbits. Zhong nan Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 2017;45(5):471‐473. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi J‐f, Zhang Y, Zhang X‐h, et al. Neu‐P11 reduces IOP through inhibiting oxidative stress level of acute high IOP rats. Zhong Guo Yao Li Xue Tong Bao. 2017;5:637‐641. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aihara M, Lindsey JD, Weinreb RN. Episcleral venous pressure of mouse eye and effect of body position. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27(6):355‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zamora DO, Kiel JW. Topical proparacaine and episcleral venous pressure in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(6):2949‐2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ripa M, Schipa C, Kopsacheilis N, et al. The impact of steep Trendelenburg position on intraocular pressure. J Clin Med. 2022;11(10):2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Friberg TR, Sanborn G, Weinreb RN. Intraocular and episcleral venous pressure increase during inverted posture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103(4):523‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. March WF, Gherezghiher T, Nordquist R, Koss M. Ultrastructural and pharmacologic studies on laser‐induced glaucoma in primates and rabbits. Lasers Surg Med. 1984;4(4):329‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gherezghiher T, March WF, Nordquist RE, Koss MC. Laser‐induced glaucoma in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 1986;43(6):885‐894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim Y, Yang J, Kim JY, Lee JM, Son WC, Moon B. HL3501, a novel selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist, lowers intraocular pressure (IOP) in animal glaucoma models. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2022;11(2):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Donia M, Osman R, Awad G, et al. Polypeptide and glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide as stabilizing polymers in nanocrystals for a safe ocular hypotensive effect. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;162:1699‐1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lorenzetti OJ. Effects of corticosteroids on ocular dynamics in rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;175(3):763‐772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qin Y, Lam S, Yam GHF, et al. A rabbit model of age‐dependant ocular hypertensive response to topical corticosteroids. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(6):559‐563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. ElGohary AA, Elshazly LH. Photopic negative response in diagnosis of glaucoma: an experimental study in glaucomatous rabbit model. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8(3):459‐464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhao J, Zhang Q. Ultrastructural changes of the trabecular meshwork in glucocorticoid induced glaucoma. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2010;25(2):119‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ticho U, Lahav M, Berkowitz S, Yoffe P. Ocular changes in rabbits with corticosteroid‐induced ocular hypertension. Brit J Ophthalmol. 1979;63(9):646‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang H, Zhao G‐h, Zhang Q, et al. Relationship between glucocorticoid receptors in the peripheral blood lymphocytes and trabecular meshwork and glucocorticoid induced glaucoma. Zhong Hua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2006;5:431‐435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel PD, Kodati B, Clark AF. Role of glucocorticoids and glucocorticoid receptors in glaucoma pathogenesis. Cells‐Basel. 2023;12(20):2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakagawa H, Koike N, Ehara T, et al. Corticosteroid eye drop instillation aggravates the development of acanthamoeba keratitis in rabbit corneas inoculated with acanthamoeba and bacteria. Sci Rep‐UK. 2019;9(1):1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ding M, Guo D, Wu J, et al. Effects of glucocorticoid on the eye development in Guinea pigs. Steroids. 2018;139:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carnahan MC, Goldstein DA. Ocular complications of topical, peri‐ocular, and systemic corticosteroids. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11(6):478‐483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang Q, Wang J, Lin X, et al. Chronic ocular hypertension in rabbits induced by limbal buckling. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(1):144‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Q, Lin X, Wang J. An optimized method for retrograde labelling and quantification of rabbit retinal ganglion cells. Exp Eye Res. 2023;229:109432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Minhas G, Sharma J, Khan N. Cellular stress response and immune signaling in retinal ischemia–reperfusion injury. Front Immunol. 2016;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Y‐l, Liang W‐f, Zhang T‐h. Fluoographic changes in rabbit retinal vessels after ocular hypertension. Yi Xue Dong Wu Fang Zhi. 2012;1:45‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Song G, Yang X‐g, Liao J. The variation of four amino acids release of the retina in acute ocular hypertension in rabbits. Zhong Hua Yan Di Bing Za Zhi. 2002;18(2):2210. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang K‐y, Zhang X‐q, Liu Z‐c. Time for establishing an animal model of acute high intraocular pressure. Zhong Guo Zu Zhi Gong Cheng Yan Jiu. 2013;46:8043‐8048. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shibata M, Sugiyama T, Kurimoto T, et al. Involvement of glial cells in the autoregulation of optic nerve head blood flow in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):3726‐3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Okuno T, Oku H, Sugiyama T, Ikeda T. Glutamate level in optic nerve head is increased by artificial elevation of intraocular pressure in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82(3):465‐470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallée J. Cannabidiol and the canonical WNT/β‐catenin pathway in glaucoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dong C, Guo Y, Agey P, et al. α2 adrenergic modulation of NMDA receptor function as a major mechanism of RGC protection in experimental glaucoma and retinal excitotoxicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Staubli U, Rangel‐Diaz N, Alcantara M, et al. Restoration of visual performance by d ‐serine in models of inner and outer retinal dysfunction assessed using sweep VEP measurements in the conscious rat and rabbit. Vision Res. 2016;127:35‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kageyama T, Ishikawa A, Tamai M. Glutamate elevation in rabbit vitreous during transient ischemia‐reperfusion. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2000;44(2):110‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kim JM, Kim YJ, Kim DM. Increased expression of oxyproteins in the optic nerve head of an in vivo model of optic nerve ischemia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sgambellone S, Marri S, Villano S, et al. NCX 470 exerts retinal cell protection and enhances ophthalmic artery blood flow after ischemia/reperfusion injury of optic nerve head and retina. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2023;12(9):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oku H, Sugiyama T, Kojima S, Watanabe T, Azuma I. Experimental optic cup enlargement caused by endothelin‐1‐induced chronic optic nerve head ischemia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;44(Suppl 1):S74‐S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bunt‐Milam AH, Dennis MB Jr, Bensinger RE. Optic nerve head axonal transport in rabbits with hereditary glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 1987;44(4):537‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Solomon AS. Congenital glaucoma in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:968. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ueno A, Tawara A, Kubota T, et al. Histopathological changes in iridocorneal angle of inherited glaucoma in rabbits. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1999;237(8):654‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Knepper PA, McLone DG, Goossens W, vanden Hoek T, Higbee RG. Ultrastructural alterations in the aqueous outflow pathway of adult buphthalmic rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52(5):525‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sun W, Shen JH, Shetlar DJ, Joos KM. Endoscopic goniotomy with the free electron laser in congenital glaucoma rabbits. J Glaucoma. 2000;9(4):325‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bastia E, Toris CB, Brambilla S, et al. NCX 667, a novel nitric oxide donor, lowers intraocular pressure in rabbits, dogs, and non‐human primates and enhances TGFβ2‐ induced outflow in HTM/HSC constructs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(3):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schmitt HM, Grosser JA, Schlamp CL, Nickells RW. Targeting HDAC3 in the DBA/2J spontaneous mouse model of glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2020;200:108244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stanescu‐Segall D, Birke K, Wenzel A, et al. PAX6 expression and retinal cell death in a transgenic mouse model for acute angle‐closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(6):426‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nakamura‐Yanagidaira T, Takahashi Y, Sano K, Murata T, Hayashi T. Development of spontaneous neuropathy in NF‐κBp50‐deficient mice by calcineurin‐signal involving impaired NF‐κB activation. Mol Vis. 2011;17:2157‐2170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bejjani BA, Lewis RA, Tomey KF, et al. Mutations in CYP1B1, the gene for cytochrome P4501B1, are the predominant cause of primary congenital glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(2):325‐333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nishida S, Uchida H, Takeuchi M, Sui GQ, Mizutani S, Iwaki M. Scanning electron microscope study of the rabbit anterior chamber angle. Med Mol Morphol. 2005;38(1):54‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pang Y. Morphology study on uveoscleral pathway post‐trabeculectomy with sclera concave Pool in rabbit. MA Dissertation. University of Nan Chang. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhao J, Zhu T, Chen W, et al. Optic neuropathy and increased retinal glial fibrillary acidic protein due to microbead‐induced ocular hypertension in the rabbit. Int J Ophthalmol‐Chi. 2016;9(12):1732‐1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nakamura Shibasaki M, Ko JA, Takenaka J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase and cytokine expression in tenon fibroblasts during scar formation after glaucoma filtration or implant surgery in rats. Cell Biochem Funct. 2013;31(6):482‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wong NK, Yip SP, Huang C. Establishing functional retina in a dish: Progress and promises of induced pluripotent stem cell‐based retinal neuron differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(17):13652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Artero‐Castro A, Rodriguez‐Jimenez FJ, Jendelova P, VanderWall KB, Meyer JS, Erceg S. Glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease caused by intrinsic vulnerability factors. Prog Neurobiol. 2020;193:101817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Clevers H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell. 2016;165(7):1586‐1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]