Abstract

Flavonoids are natural products with high biological activity and potential applications. Prenylation increases the lipophilicity of flavonoids, endowing them with specific functions, selectivity, and pharmacological properties. However, traditional methods of plant extraction and chemical synthesis are insufficient to meet the demand for prenylflavonoids. Heterologous biosynthesis of prenylflavonoids in microorganisms provides an alternative approach. Compared with plant prenyltransferases, microbial prenyltransferases showed broad substrate specificity, which is more conducive to the biosynthesis of diverse prenylflavonoids. In this study, we cloned 31 dimethylallyltryptophan synthase prenyltransferases from five fungal species and tested candidate substrates. The products of Ad03 and Ao01 were identified, resulting in two unnatural prenylflavonoids and four natural prenylflavonoids. We constructed the isopentenol utilization pathway in Escherichia coli to develop the efficient dimethylallyl diphosphate synthesis pathway for 6-prenylsilybin (6-PS) synthesis. By optimizing the whole cell catalysis and two-phase reaction system, the 6-PS production titer reached 176 mg/L and the yield of silybin was 88%. Our study provides an efficient method for prenylflavonoids production.

1. Introduction

Flavonoids are widely distributed in plant secondary metabolites with various biological and pharmacological activities. Prenylation enhances the lipophilicity of flavonoids, improves their affinity to cell membranes, and enhances their interaction with target proteins.1−6 Compared to flavonoids, prenylflavonoids have many advantages in terms of bioavailability and bioactivity, such as cytotoxicity, antibacterial activity, and antioxidant activity.7 For example, 8-prenylapigenin exerted a pronounced toxicity in H4IIE cells, while the nonprenylated apigenin showed no cytotoxic activity.8

Prenyltransferases (PTs) are responsible for the prenylation of flavonoids in nature. Plant flavonoid PTs are membrane-bound proteins belonging to the UbiA superfamily. They usually have strict substrate and donor specificity, and heterologous expression is difficult. Although prenylflavonoids such as 8-prenylnaringenin9 and icaritin10 have been produced by engineered microorganisms with plant PTs, their production is very low. Unlike plant PTs, most microbial PTs are soluble proteins from the dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (DMATS) superfamily. Microbial PTs may not participate in the synthesis of prenylflavonoids naturally, but because of their broad substrate spectrum, they can also catalyze the prenylations of several flavonoids with the dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) donor.11−16 As soluble proteins, they are suitable for heterologous expression in Escherichia coli.17 In addition, due to the broad substrate spectrum of microbial PTs, they could be employed for the synthesis of structurally diverse prenylflavonoids, including some unnatural prenylflavonoids.

Prenylflavonoids are often rare in nature, making their identification and availability for practical applications challenging.18 Chemical synthesis is difficult to satisfy the demands for high stereochemistry and is not friendly to the environment.17,19 Therefore, we speculated that the efficient heterologous expression of PTs in microorganisms combined with whole-cell catalysis is an effective method to produce prenylflavonoids.

However, the prenylflavonoid production often suffered from an inefficient DMAPP/IPP supply in the E. coli chassis. To increase the supply of DMAPP, the biosynthetic pathways of MVA and MEP were enhanced.20−22 For example, the truncated form of 3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (tHMG1) was used in the MVA pathway.23 In recent years, an artificial pathway has been established for the DMAPP/IPP synthesis. The isopentenol utilization pathway (IUP) produces DMAPP from prenol through consecutive two-step reactions catalyzed by promiscuous kinase (PK) and isopentenyl phosphate kinase (IPK).24,25 The production titer of 6-prenylnaringenin was increased from 2.6 mg/L (MVA + MEP) to 7.4 mg/L (IUP + MEP) by enhancing the donor DMAPP synthesis pathway and further increased to 69.9 mg/L by optimizing the process for whole-cell catalysis.26 Through coupling the IUP pathway, the production titer of licoflavanone was increased to 142.1 mg/L in a shake flask.27

Flavonoids such as silybin (sil), daidzein (dai), and baicalein (bai) are beneficial to human health and widely used. The prenylation of these flavonoids may give compounds with improved therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, this research is committed to pioneering the synthesis of structurally diverse prenylflavonoids. We provide a microbial whole-cell catalysis platform to synthesize prenylflavonoids efficiently.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Chemicals, and Media

Flavonoids such as silybin, baicalein, and daidzein were purchased from Nantong Feiyu Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China). Prenol (3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). DMAPP was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). LB medium contained 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L sodium chloride. TB-glucose, TB-glycerol (TB-Gly), TB-maltose, TB-lactose (TB-Lac), and TB-arabinose contained the same components (12 g/L tryptone, 24 g/L yeast extract, 2.32 g/L KH2PO4, and 12.54 g/L K2HPO4) but a different carbon source (10 g/L glucose, 10 g/L glycerol, 10 g/L maltose, 10 g/L lactose, and 10 g/L arabinose, respectively).

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

A public Hidden Markov Model (PF11991, http://pfam.xfam.org/) was used to predict the PTs of Aspergillus nidulatus, Aspergillus oryzae, Claviceps purpurea, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus niger. The amino acid sequences of the candidate PTs were analyzed using MAFFT software, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with Geneious R8 software, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Accession numbers of the related PTs are listed in Table S3.

2.3. Plasmid Construction

All plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the relevant primers are listed in Table S1. The strains were grown at 37 °C in TB-Gly medium supplemented with antibiotics when required. PT candidate genes were deposited in the Registry and database of bioparts for synthetic biology (https://www.biosino.org); accession numbers are OENC366060-OENC366090. They were constructed on pGEX-4T-1 plasmids digested by XhoI and BamHI or pET-28a plasmids digested by NcoI and SalI to form BL21-PTs strains. The IUP was reconstructed in E. coli by introducing PK and IPK. The PK gene from E. coli (Thim) and the codon-optimized IPK gene from Thermoplasma acidophilum (TaIPK) were selected. Thim was constructed on the pETDuet-1 plasmid digested by NcoI and BamHI to form pETDuet-1-Thim strain. Then, TaIPK was constructed onto the plasmid pETDuet-1-Thim cut by NdeI and XhoI, respectively, to form the IUP strain pETDuet-1-Thim-TaIPK (TTa).

Table 1. List of Plasmids and Strains Used in This Study.

| description | source | |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEX-4T-1 | E. coli expression vector | novagen |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ad01 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad01 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ad02 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad02 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ad03 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad03 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ad04 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad04 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ad05 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad05 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao01 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao01 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao02 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao02 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao03 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao03 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao04 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao04 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao05 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao05 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao06 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao06 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao07 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao07 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao08 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao08 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ao09 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao09 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ag01 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ag01 | in this study |

| pGEX-4T-1-Ag02 | pGEX-4T-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ag02 | in this study |

| pET28a-Cp01 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding Cp01 | in this study |

| pET28a-Cp02 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding Cp02 | in this study |

| pET28a-Cp03 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding Cp03 | in this study |

| pET28a-Cp04 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding Cp04 | in this study |

| pET28a-Cp05 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding Cp05 | in this study |

| pET28a-At01 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At01 | in this study |

| pET28a-At02 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At02 | in this study |

| pET28a-At03 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At03 | in this study |

| pET28a-At04 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At04 | in this study |

| pET28a-At05 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At05 | in this study |

| pET28a-At06 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At06 | in this study |

| pET28a-At07 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At07 | in this study |

| pET28a-At08 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At08 | in this study |

| pET28a-At09 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At09 | in this study |

| pET28a-At10 | pET28a plasmid containing the gene encoding At10 | in this study |

| pETDuet-1 | E. coli expression vector | Novagen |

| pCDFDuet-1 | E. coli expression vector | Novagen |

| pETDuet-1-Thim | pETDuet-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Thim | in this study |

| pETDuet-1-TTa | pETDuet-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Thim and TaIPK | in this study |

| pCDFDuet-1-Ad03 | pCDFDuet-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ad03 | in this study |

| pCDFDuet-1-Ao01 | pCDFDuet-1 plasmid containing the gene encoding Ao01 | in this study |

| Strains | ||

| BL21 | general expression host | Invitrogen |

| BL21-pGEX | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1 | in this study |

| BL21-Ad01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ad01 | in this study |

| BL21-Ad02 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ad02 | in this study |

| BL21-Ad03 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ad03 | in this study |

| BL21-Ad04 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ad04 | in this study |

| BL21-Ad05 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ad05 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao01 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao02 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao02 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao03 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao03 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao04 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao04 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao05 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao05 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao06 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao06 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao07 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao07 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao08 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao08 | in this study |

| BL21-Ao09 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ao09 | in this study |

| BL21-Ag01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ag01 | in this study |

| BL21-Ag02 | BL21 harboring plasmid pGEX-4T-1-Ag02 | in this study |

| BL21-Cp01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-Cp01 | in this study |

| BL21-Cp02 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-Cp02 | in this study |

| BL21-Cp03 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-Cp03 | in this study |

| BL21-Cp04 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-Cp04 | in this study |

| BL21-Cp05 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-Cp05 | in this study |

| BL21-At01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At01 | in this study |

| BL21-At02 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At02 | in this study |

| BL21-At03 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At03 | in this study |

| BL21-At04 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At04 | in this study |

| BL21-At05 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At05 | in this study |

| BL21-At06 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At06 | in this study |

| BL21-At07 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At07 | in this study |

| BL21-At08 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At08 | in this study |

| BL21-At09 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At09 | in this study |

| BL21-At10 | BL21 harboring plasmid pET28a-At10 | in this study |

| TTa | BL21 harboring plasmid pETDuet-1-Thim-TaIPK | in this study |

| TTa-Ad03 | BL21 harboring plasmid pETDuet-1-Thim-TaIPK and pCDFDuet-1-Ad03 | in this study |

| TTa-Ao01 | BL21 harboring plasmid pETDuet-1-Thim-TaIPK and pCDFDuet-1-Ao01 | in this study |

2.4. Functional Identification of Candidate PTs

The BL21-PTs strains and negative control (BL21) were cultured overnight in 5 mL of LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Seed culture (1 mL) was added to 50 mL of fresh LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. The cultures were induced to express candidate PTs by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.2 mM at an OD600 of ∼0.8, followed by incubation at 16 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000g for 5 min and suspended in 3 mL of 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and disrupted using a French press (25 kpsi). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used as a crude enzyme solution for enzymatic assays.

Enzymatic assays for PTs were carried out in a 50 μL volume containing 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 40 μL of crude enzyme solution, 0.4 mM DMAPP as the prenyl donor, and 0.4 mM flavonoid substrates as the prenyl receptor for 10 h at 37 °C. The reaction products were extracted by adding 100 μL of ethyl acetate, and the organic phase was evaporated and dissolved in 50 μL of methanol for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.5. DMAPP Standard and Sample Preparation

The DMAPP standard was obtained by dissolving 100 ng of DMAPP in 1 mL of 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (containing 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0): methanol = 1:9.

The TTa sample was obtained as follows. The TTa strain was cultured in 5 mL of TB-Gly medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Seed culture (250 μL) was added to 25 mL of fresh TB-Gly medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. The cultures were induced to express recombinant Thim and TaIPK by adding 0.2 mM IPTG and 20 mM prenol at an OD600 of ∼0.8, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 6 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000g for 10 min and washed with 200 μL of 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (containing 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) for 3 times. Then, the cells were suspended with 400 μL of lysis buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (containing 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0): methanol = 1:9] and placed overnight at −20 °C. The cells were vortexed and centrifuged at 4 °C and 15,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was a mass spectrometry sample. The BL21 sample was obtained in the same way. All metabolite concentrations are reported as means ± SD of three biological replicates.

2.6. Construction of Strains for Whole-Cell Catalysis

Ad03 from Aspergillus nidulans and Ao01 from A. oryzae were constructed onto the pCDFDuet-1 plasmid cut by NcoI and BamHI, respectively, to form PT plasmids: pCDFDuet-1-Ad03 and pCDFDuet-1-Ao01. The plasmids of PT and TTa were simultaneously transferred into BL21 (DE3) to construct strains containing the IUP.

The recombinant strain TTa-Ad03 was inoculated into 5 mL of fresh TB-Gly medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/mL spectinomycin. The recombinant strains were grown at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.8. 0.2 mM IPTG was added and induced at 30 °C for 6 h. Then, silybin (20 mg/L) and prenol (20 mM) were added to the broth. The fermentation broths were incubated at 30 °C and 250 rpm for 24 h. 200 μL of ethyl acetate was added to 200 μL of the fermentation broth for shaking extraction for 1 h. The supernatant was harvested by centrifugation at 12,000g for 1 min. The extract was evaporated and resuspended in 50 μL of methanol for HPLC analysis.

The optimized fermentation method was to inoculate the recombinant strain TTa-Ad03 into fresh TB-Lac medium containing the corresponding antibiotics. The recombinant strain was cultured at 37 °C to OD600 of 0.8. 0.2 mM IPTG (0.2 mM) was added and induced at 30 °C for 6 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000g for 10 min and suspended with 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) until OD600 was 200. The whole-cell catalysis reaction system consisted of 200 μL of cell suspension at an OD600 of 200, 200 mg/L silybin, and 3 mM prenol. The fermentation solution was cultured at 30 °C and 250 rpm for 24 h. The samples were extracted with twice the volume of ethyl acetate, dissolved in 50 μL methanol, and analyzed by HPLC. All product concentrations are reported as means ± SD of three biological replicates.

2.7. Optimization of the Process for Whole-Cell Catalysis

The whole-cell catalysis process of silybin using the TTa-Ad03 strain was optimized. The TTa-Ad03 strain was inoculated in TB-Gly medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin and grown at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.8. A final concentration of 0.2 mM IPTG was added, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 6 h. Then, silybin and prenol were added. The fermentation solution was incubated at 30 °C and 200 rpm for 24 h. The effects of different media (LB, TB-glucose, TB-Gly, TB-maltose, TB-Lac, or TB-arabinose), silybin (10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, or 1000 mg/L), prenol (0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, or 30 mM), and cell density OD600 (20, 50, 100, 200 or 500) were determined. The samples were extracted with twice the volume of ethyl acetate, dissolved in 50 μL of methanol, and analyzed by HPLC. All product concentrations are reported as means ± SD of three biological replicates.

2.8. HPLC and UPLC–MS/MS Spectrometry Analysis

HPLC analysis was performed using a Shimadzu LC 20A system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a LC20ADXR pump, an autosampler, a binary pump, and a diode array detector. To analyze the products, chromatographic separation was performed at 35 °C with a Welch Boltimate C18 (2.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) column. The gradient elution system consisted of 0.1% acetic acid/water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The extract was separated using the following gradient: 0–2 min (15% B), 2–16 min (15–70% B), 16–18 min (95% B), and 18–20 min (15% B). The flow rate was kept at 0.45 mL/min. The products were monitored at a 290 nm absorbance.

Mass spectrometry was performed on a UPLC instrument combined with a QTRAP 6500+ MS system equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (AB SCIEX). Instrument control and data acquisition were performed using Analyst 1.6.3 software (AB SCIEX), and data processing was performed using MultiQuant 3.0.2 software (AB SCIEX). The compounds were quantified by calculating the area of each individual peak and comparing it to standard curves. DMAPP was separated with an XSelect HSS T3 column (2.5 μm, 3.0 mm × 100 mm). The UPLC method for DMAPP is shown in Table S4. The optimized ESI operating parameters for negative mode were as follows: IS, −4500 V; CUR, 35 psi; transmission electron microscopy 500 °C; GS1, 50 psi; GS2, 50 psi. All analytes were detected using the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, and the specific MRM parameters for each analyte are given in Table S5.

2.9. Nuclear magnetic resonance Analysis

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were generated using the Bruker ADVANCE III 500 instrument (1H: 500 MHz, 13C: 125 MHz; Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA), with chemical shift values expressed as ppm relative to tetramethylsilane (δH 0.00 and δC 0.00 ppm), using residual chloroform (δH 7.26 and δC 77.16 ppm) as a standard.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mining and Identification of PTs in the DMATS Superfamily

The transcriptome data of A. nidulatus, A. oryzae, C. purpurea, A. terreus, and A. niger were obtained from a public database. A specific Hidden Markov Model (PF11991) was used to predict the PTs. We predicted five candidate genes from A. nidulans, nine candidate genes from A. oryzae, five candidate genes from C. purpurea, ten candidate genes from A. terreus, and two candidate genes from A. niger. These candidate genes were cloned using cDNA as a template and overexpressed in E. coli. To further analyze the relationships between the candidate PTs and other known DMATS PTs, we selected the DMATS PTs mined in this study as the candidate PTs, and we selected functionally identified DMATS PTs from the published literature as known DMATS PTs to generate a phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). We found that the candidate PTs have a closer evolutionary relationship with the fungal source PTs. Ad03, Ad05 and Cp02 are reported PTs NptA, TdiB and DmaW, while other candidate PTs are novel. Ad03 (NptA) can catalyze the prenylation of tryptophan to participate in nidulanin A synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans.28 Ad05 (TdiB) can catalyze the prenylation of didemethylasterriquinone D to produce asterriquinone C-1, a step in the biosynthesis of aterrequinone A.29 Cp02 (DmaW) can catalyze the prenylation of tryptophan and its derivatives at C-4.30

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of DMATS PTs. The tree was constructed via the neighbor-joining algorithm. Accession numbers are provided in Table S3. Reported bacterial source PTs are shown in blue font, reported fungal source PTs are shown in black font, and the fungal source PTs mined for this study are shown in red font.

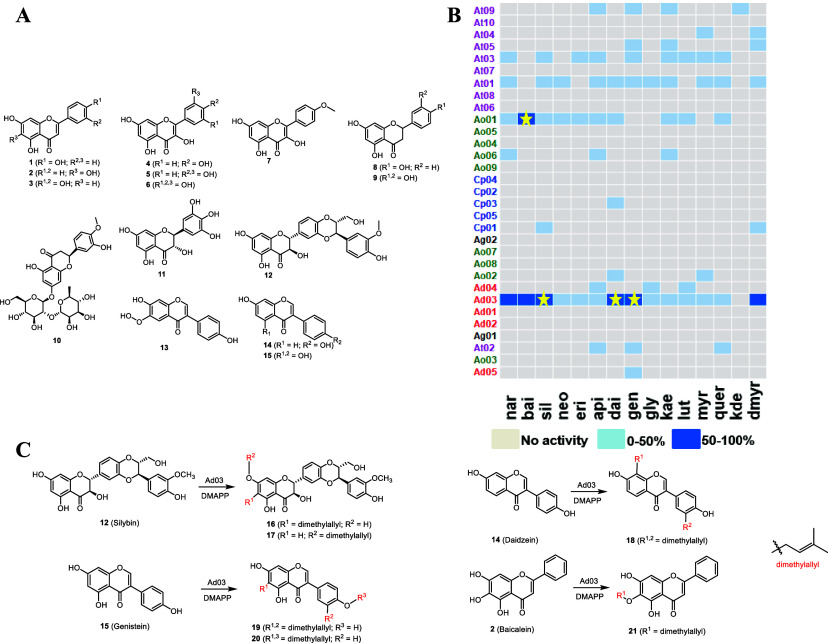

However, the catalytic activity of all candidate PTs with respect to flavonoids is unknown. We selected 15 flavonoid substrates of different flavonoid subclasses and systematically identified the functions of these 31 candidate PTs. The flavonoid substrates include apigenin (api, 1), baicalein (bai, 2), luteolin (lut, 3), kaempferol (kae, 4), quercetin (quer, 5), myricetin (myr, 6), kaempferide (kde, 7), naringenin (nar, 8), eriodictyol (eri, 9), neohesperidin (neo, 10), dihydromyricetin (dmyr, 11), silybin (sil, 12), glycitein (gly, 13), daidzein (dai, 14), and genistein (gen, 15). The BL21-PTs strains were cultured to induce the expression of candidate PTs, and crude enzyme solution was obtained for the in vitro enzymatic reaction. The products in the reaction system were analyzed by HPLC. Compared with negative control (nonloaded plasmid), any additional peaks might correspond to new products formed, and the samples with high yield were identified by mass spectrometry. HPLC analysis showed that Ad03 could efficiently catalyze the prenylation of various types of flavonoids, while Ao01 could efficiently catalyze only the prenylation of baicalein.

Compared with the reported literature data,31 the minor prenylation product of silybin was elucidated as 7-O-prenylsilybin (17). The major prenylation product share the same molecular weight with product 17, while 1H shift of methylene in the prenyl group was lower than that in compound 17 (3.52 ppm VS 4.63 ppm), which suggested that the prenyl group was added on a carbon of the aromatic ring. The HMBC of methylene-H in the prenyl group with C7 and H8 with C9 suggested that the major prenylation product 16, named as 6-prenylsilybin (6-PS), was prenylated on C6 of silybin. One of diprenylation products of genistein was elucidated as lupalbigenin 19 according to the literature reported data.32,33 Compared the 1H NMR spectrum of prenylation products 19 and 20, one of the prenyl group in compound 20 was O-prenylation and the position was confirmed as 4′-O-prenylation according NOE correlation between H1″ (4.54 ppm) and H3′ (H5′) (6.98 ppm). The prenylation products 18 and 21 were confirmed via comparing their spectra with the literature reported data, and all the spectra were consistent.34,35 In summary, we obtained two unnatural prenylflavonoids (6-PS, 16 and 20) and four reported prenylflavonoids (7-O-prenylsilybin, 17; erysubin F, 18; lupalbigenin, 19; and 6-O-prenylbaicalein, 21) (Figures 2 and S9–S34).

Figure 2.

Functional characterization of candidate PTs. (A) Structures of the flavonoids assayed as prenyl acceptors. (B) HPLC analysis of different flavonoid substrates catalyzed by PT candidate genes. Gray is inactive, light blue is less than 50% conversion, and dark blue is greater than 50% conversion. The yellow stars represent the product structures are determined. (C) Identified products from enzymatic reactions by Ad03 with silybin (12), daidzein (14), and genistein (15) and product from enzymatic reactions by Ao01 with baicalein (2).

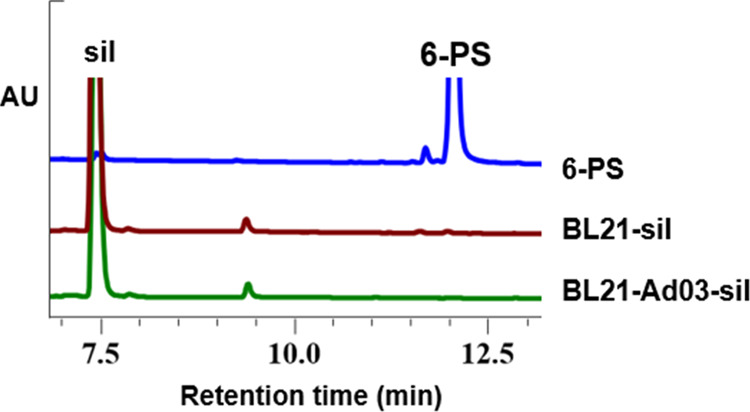

3.2. Engineering an Artificial Pathway for Efficient Biosynthesis of Prenyl Donor DMAPP in E. coli

To test the ability of the E. coli strain for prenylflavonoids production, PT Ad03 from A. nidulans, which was characterized to catalyze the biosynthesis of 6-PS from silybin, was overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21. The resulting strain was tested for the biosynthesis of 6-PS via whole-cell catalysis using silybin as a substrate. However, no detectable 6-PS could be detected by HPLC analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Production of 6-PS in the BL21 strain was analyzed by HPLC. HPLC analysis of 6-PS synthesis of Ad03 in wild-type chassis BL21.

The PTs catalyze the prenylation of flavonoids and require DMAPP as a prenyl donor. Although E. coli has a native MEP pathway for DMAPP synthesis, we hypothesized that the DMAPP content in wild-type E. coli might not be enough to support the prenylation reaction (Figure 4A). Therefore, we consider introducing exogenous pathways to increase the intracellular DMAPP content. In addition to the MEP pathway, the MVA pathway is a well-known pathway for DMAPP/IPP synthesis, which has also been successfully reconstructed in E. coli.21 However, the long length and complex regulation of the MVA and MEP pathways make it a challenging task to improve the metabolic flux to produce DMAPP. We constructed a two-step IUP in E. coli, combining PK enzyme (Thim from E. coli) and IPK enzyme (TaIPK from T. acidophilum) to obtain the TTa strain. The contents of DMAPP and IPP in strains were tested by mass spectrometry analysis (Figure 4B). Compared with wild-type strain BL21, DMAPP and IPP contents of the strain TTa were significantly increased, with 636 ng/mL, which was 212 times higher than that of BL21. Therefore, the TTa strain was selected to construct subsequent PT strains.

Figure 4.

Construction of an E. coli chassis-enhanced DMAPP synthesis system. (A) Schematics of different chassis strains. The wild-type strain BL21 contains the native MEP pathway of E. coli to synthesize DMAPP; the exogenous IUP pathway was introduced by the TTa strain to enhance the supply of DMAPP. (B) DMAPP + IPP content was quantified by mass spectrometry. DMAPP with 100 ng/mL was used as the standard sample to detect the DMAPP + IPP content in BL21 and TTa strains.

3.3. Efficient Biosynthesis of Prenylflavonoid 6-PS in the Engineered E. coli Strain

To test capacity of the strain TTa for prenylflavonoid synthesis, Ad03 was introduced, and the resulting strain was used for 6-PS production (Figure 5A). As detected by HPLC, 0.91 mg/L 6-PS can be obtained from 20 mg/L silybin, representing a conversion ratio of 0.45%. To further increase the whole-cell catalysis efficiency, we next optimized the culture media, silybin concentration, prenol concentration, and OD600. As shown in Figure 5, the 6-PS production titer was 0.91 mg/L in TB-Gly, which was higher than those in TB-glucose and LB, so we chose to conduct subsequent optimization experiments in TB-Gly medium. When the concentration of silybin was higher than 200 mg/L, the yield decreased significantly, while 6-PS production increased when the addition of silybin was no more than 200 mg/L. The highest 6-PS production titer reached 4.1 mg/L, so 200 mg/L silybin was selected for the following experiment. The same results were observed for prenol. The maximal 6-PS production titer was 8.4 mg/L when the addition of prenol was 3 mM, so we chose 3 mM prenol to conduct following experiment.

Figure 5.

Biosynthesis of 6-PS in the engineered E. coli strain. (A) Prenylation of silybin by Ad03. (B) Effect of culture mediums on 6-PS production. (C) Effect of silybin concentration on 6-PS production. (D) Effect of prenol concentration on 6-PS production. (E) Effect of OD600 on 6-PS production.

Stabilizing the fermentation solution at a stable cell density (OD600) is also a common strategy for whole-cell catalysis. Choosing a suitable cell density can catalyze the reaction more efficiently. We tested OD600 at 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 with a pH of 7.5 buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl to investigate the effect of cell density on the 6-PS production titer . When OD600 was from 20 to 200, 6-PS production increased with the increase of cell density, while 6-PS production reduced when OD600 was 500. The results showed that the optimal OD600 was 200 and the production titer was 95 mg/L (Figure 5E).

3.4. Effects of Organic Reagents and Carbon Sources on 6-PS Production

Two-phase catalysis can change the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions at the two-phase interface.36,37 We tested the effect of different organic reagents (n-hexane, ethyl acetate, ethyl alcohol, methanol, isopropanol, cyclohexane, and acetonitrile) on the 6-PS production titer and found that n-hexane could significantly increase the titer (Figure S35). Further testing of different doses of n-hexane showed that 5% of the reaction volume had the best catalytic effect on 6-PS production, with the production titer reaching 154 mg/L and the yield of silybin reaching 77% (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of the organic phase on the production of 6-PS. The effect of 0–100% n-hexane on the production of 6-PS.

Different carbon sources may affect the metabolism of the TTa strain and the production of 6-PS. Therefore, we tested their effects on 6-PS production. Among 15 carbon sources, 6-PS production was determined in TB-glucose, TB-Gly, TB-maltose, TB-Lac, and TB-arabinose. With lactose as the carbon source, the production titer of 6-PS was greatly increased (Figure 7A). In the optimal catalytic system, the 6-PS titer of lactose as a carbon source reached 176 mg/L, and the yield of silybin was 88%, which was higher than that of glycerol as a carbon source, 154 mg/L (Figure 7B). It is currently the highest output value of prenylflavonoid cell factory.

Figure 7.

Effect of carbon sources on the production of 6-PS. (A) Effect of carbon sources on 6-PS production. (B) Production of 6-PS with glycerol and lactose as carbon sources in an optimal catalytic system.

3.5. Production of Other Prenylflavonoids by the Engineered Platform Strain

So far, we have successfully constructed a DMAPP/IPP high-yielding chassis strain TTa. The target product was successfully detected by introducing PT Ad03. After several rounds of condition optimization and two-phase catalysis, E. coli cell factory with a high yield of prenylflavonoid was finally obtained.

But whether this cell factory is universal is a question we want to explore. We first put daidzein, another type of flavonoid substrate, into the constructed TTa-Ad03 strain. The corresponding target product (erysubin F) can be detected at a titer of 53.5 mg/L, indicating that this chassis is suitable for different substrates. Then, we introduced different PTs, such as Ao01, which can produce the corresponding target product (6-O-prenylbaicalein) at a titer of 32 mg/L, indicating that this chassis is suitable for different PTs (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Prenylflavonoid cell factory we constructed can catalyze daidzein and baicalein. (A) HPLC analyses and catalytic reaction of 200 mg/L daidzein catalyzed by Ad03. (B) HPLC analyses and catalytic reaction of 200 mg/L baicalein catalyzed by Ao01.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we cloned 31 DMATS PTs from A. nidulatus, A. oryzae, C. purpurea, A. terreus, and A. niger. To investigate their catalytic activity, 15 flavonoid substrates were tested. The products of Ad03 and Ao01 were identified, resulting in two unnatural prenylflavonoids and four natural prenylflavonoids. Then, we optimized the synthesis of donor DMAPP in E. coli using PK enzyme (Thim from E. coli) and IPK enzyme (TaIPK from T. acidophilum) to construct an easily regulated two-step IUP and developed a whole-cell catalysis platform for various natural and unnatural prenylflavonoids production. Through optimizing the whole-cell catalysis, two-phase reaction system, and carbon sources, the production titer of 6-PS increased from 0.91 to 176 mg/L. Collectively, our study provides an effective way for novel prenylflavonoids production and mass production by the development of a microbial whole-cell catalysis platform.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2019YFA0905700 and 2020YFA0907900), the National Science Resource Investigation Program of China (2019FY100100), the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (153D31KYSB20170121), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB27020206), and the Strategic Biological Resources Service Network Plan of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant nos. KFJ-BRP-009 and KFJ-BRP-017-60).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c05007.

Primers used in this study, candidate PTs in A. nidulatus, A. oryzae, C. purpurea, A. terreus, and A. niger, phylogenetic analysis of PTs belonging to the DMATS superfamily, the UPLC method for DMAPP, the specific MRM parameters for DMAPP, HPLC analysis of the production of silybin catalyzed by Ad03, HPLC analysis of the production of genistein catalyzed by Ad03, HPLC analysis of the production of daidzein catalyzed by Ad03, HPLC analysis of the production of baicalein catalyzed by Ao01, LC–MS analyses of the production of silybin catalyzed by Ad03, LC–MS analyses of the production of genistein catalyzed by Ad03, LC–MS analyses of the production of daidzein catalyzed by Ad03, LC–MS analyses of the production of baicalein catalyzed by Ao01, NMR spectra of compounds 6-PS (16), 7-O-prenylsilybin (17), erysubin F (18), lupalbigenin (19), 20, and 6-O-prenylbaicalein (21), effect of different organic reagents on the production of 6-PS, and NMR data of compounds 6-PS (16), 7-O-prenylsilybin (17), lupalbigenin (19), 20, erysubin F (18), and 6-O-prenylbaicalein (21) (PDF)

Author Contributions

Z.F.: Conceptualization, investigation, and writing—original draft. Y.W.: Investigation, and writing—review and editing. T.N.: Investigation. J.C.: Investigation. Z.Z.: Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, and writing—review and editing. Z.L.: Conceptualization and supervision. P.W.: Investigation, writing—review and editing, and supervision. X.Y.: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pietta P. G. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63 (7), 1035–1042. 10.1021/np9904509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Mukwaya E.; Wong M. S.; Zhang Y. A systematic review on biological activities of prenylated flavonoids. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52 (5), 655–660. 10.3109/13880209.2013.853809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta B.; Vitali A.; Menendez P.; Misiti D.; Monache G. Prenylated flavonoids: pharmacology and biotechnology. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12 (6), 713–739. 10.2174/0929867053202241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R.; Fan Y. H.; Ma C. M. Identification and Enrichment of alpha-Glucosidase-Inhibiting Dihydrostilbene and Flavonoids from Glycyrrhiza uralensis Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65 (2), 510–515. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Wang D.; Song X. T.; Zhang Y. Z.; Ding W. N.; Peng X. L.; Zhang X. T.; Li Y. S.; Ma Y.; Wang R. L.; Yu P. Natural Prenylchalconaringenins and Prenylnaringenins as Antidiabetic Agents: alpha-Glucosidase and alpha-Amylase Inhibition and in Vivo Antihyperglycemic and Antihyperlipidemic Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65 (8), 1574–1581. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbachu O. C.; Howell C.; Simmler C.; Garcia G. R. M.; Skowron K. J.; Dong H.; Ellis S. G.; Hitzman R. T.; Hajirahimkhan A.; Chen S. N.; Nikolic D.; Moore T. W.; Vollmer G.; Pauli G. F.; Bolton J. L.; Dietz B. M. SAR Study on Estrogen Receptor alpha/beta Activity of (Iso)flavonoids: Importance of Prenylation, C-Ring (Un)Saturation, and Hydroxyl Substituents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68 (39), 10651–10663. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunassee S. N.; Davies-Coleman M. T. Cytotoxic and antioxidant marine prenylated quinones and hydroquinones. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29 (5), 513–535. 10.1039/c2np00086e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watjen W.; Weber N.; Lou Y. J.; Wang Z. Q.; Chovolou Y.; Kampkotter A.; Kahl R.; Proksch P. Prenylation enhances cytotoxicity of apigenin and liquiritigenin in rat H4IIE hepatoma and C6 glioma cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45 (1), 119. 10.1016/j.fct.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C.; Gao S.; Li H.; Lyu Y.; Yu S.; Zhou J. [N-terminal truncation of prenyltransferase enhances the biosynthesis of prenylnaringenin]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2022, 38 (4), 1565–1575. 10.13345/j.cjb.210456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.; Li C.; Li X.; Huang W.; Wang Y.; Wang J.; Zhang Y.; Yang X.; Yan X.; Wang Y.; Zhou Z. Complete biosynthesis of the potential medicine icaritin by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66 (18), 1906–1916. 10.1016/j.scib.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya-Cloutier C.; Martens B.; Schaftenaar G.; Leipoldt F.; Gruppen H.; Vincken J. P. Structural basis for non-genuine phenolic acceptor substrate specificity of Streptomyces roseochromogenes prenyltransferase CloQ from the ABBA/PT-barrel superfamily. PLoS One 2017, 12 (3), e0174665 10.1371/journal.pone.0174665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.; Gao B.; Liu X.; Ruan F.; Zhang Y.; Lou J.; Feng K.; Wunsch C.; Li S. M.; Dai J.; Sun F. Molecular insights into the enzyme promiscuity of an aromatic prenyltransferase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13 (2), 226–234. 10.1038/nchembio.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki T.; Mishima S.; Nishiyama M.; Kuzuyama T. NovQ is a prenyltransferase capable of catalyzing the addition of a dimethylallyl group to both phenylpropanoids and flavonoids. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62 (7), 385–392. 10.1038/ja.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Yang J.; Jiang Y.; Yang H.; Yun Z.; Rong W.; Yang B. Regiospecific synthesis of prenylated flavonoids by a prenyltransferase cloned from Fusarium oxysporum. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24819. 10.1038/srep24819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai S.; Okahashi N.; Asama R.; Nakamura T.; Hasunuma T.; Matsuda F.; Ishii J.; Kondo A. Synthetic production of prenylated naringenins in yeast using promiscuous microbial prenyltransferases. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2021, 12, e00169 10.1016/j.mec.2021.e00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C. J.; Lv Y. K.; Li H. B.; Zhou J. W.; Xu S. De novo biosynthesis of 8-prenylnaringenin in improved by screening and engineering of prenyltransferases and precursor pathway. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2023, 3 (4), 647–658. 10.1007/s43393-022-00133-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. M.; Jiang Y. M.; Yang J. L.; He J. R.; Sun J.; Chen F.; Zhang M. W.; Yang B. Prenylated flavonoids, promising nutraceuticals with impressive biological activities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 44 (1), 93–104. 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rainha J.; Gomes D.; Rodrigues L. R.; Rodrigues J. L. Synthetic Biology Approaches to Engineer Saccharomyces cerevisiae towards the Industrial Production of Valuable Polyphenolic Compounds. Life 2020, 10 (5), 56. 10.3390/life10050056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Ding W.; Jiang H. Engineering microbial cell factories for the production of plant natural products: from design principles to industrial-scale production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16 (1), 125. 10.1186/s12934-017-0732-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Chen J.; Zhang J.; Zhou Y.; Zhang Y.; Wang F.; Li X. Engineering Escherichia coli for production of geraniol by systematic synthetic biology approaches and laboratory-evolved fusion tags. Metab. Eng. 2021, 66, 60–67. 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V. J.; Pitera D. J.; Withers S. T.; Newman J. D.; Keasling J. D. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21 (7), 796–802. 10.1038/nbt833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitera D. J.; Paddon C. J.; Newman J. D.; Keasling J. D. Balancing a heterologous mevalonate pathway for improved isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2007, 9 (2), 193–207. 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro D. K.; Paradise E. M.; Ouellet M.; Fisher K. J.; Newman K. L.; Ndungu J. M.; Ho K. A.; Eachus R. A.; Ham T. S.; Kirby J.; Chang M. C.; Withers S. T.; Shiba Y.; Sarpong R.; Keasling J. D. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature 2006, 440 (7086), 940. 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzivasileiou A. O.; Ward V.; Edgar S. M.; Stephanopoulos G. Two-step pathway for isoprenoid synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116 (2), 506–511. 10.1073/pnas.1812935116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Zu Y.; Huang S.; Stephanopoulos G. Engineering a universal and efficient platform for terpenoid synthesis in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120 (1), e2207680120 10.1073/pnas.2207680120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C.; Liu Y.; Wu Y.; Zhao L.; Pei J. Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Prenyltransferase from Streptomyces sp. NT11 and Development of a Recombinant Strain for the Production of 6-Prenylnaringenin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69 (47), 14231–14240. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c06094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. X.; Yao W. L.; Tang Y. Y.; Ye J.; Niu T. F.; Yang L.; Wang R. F.; Wang Z. T. Coupling the Isopentenol Utilization Pathway and Prenyltransferase for the Biosynthesis of Licoflavanone in Recombinant. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72 (28), 15832–15840. 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c03655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. R.; Nielsen J. B.; Klitgaard A.; Petersen L. M.; Zachariasen M.; Hansen T. J.; Blicher L. H.; Gotfredsen C. H.; Larsen T. O.; Nielsen K. F.; Mortensen U. H. Accurate prediction of secondary metabolite gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110 (1), E99–E107. 10.1073/pnas.1205532110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P.; Weber M.; Hoffmeister D. The Aspergillus nidulans enzyme TdiB catalyzes prenyltransfer to the precursor of bioactive asterriquinones. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45 (3), 302. 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner U.; Ahimsa-Muller M. A.; Markert A.; Kucht S.; Gross J.; Kauf N.; Kuzma M.; Zych M.; Lamshoft M.; Furmanowa M.; Knoop V.; Drewke C.; Leistner E. Molecular characterization of a seed transmitted clavicipitaceous fungus occurring on dicotyledoneous plants (Convolvulaceae). Planta 2006, 224 (3), 533. 10.1007/s00425-006-0241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K.; Yu X.; Xie X.; Li S. M. Complementary Flavonoid Prenylations by Fungal Indole Prenyltransferases. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78 (9), 2229–2235. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horticultural G. B. R. New isoflavonoids from root bark of kowhai (Sophora microphylla). Aust. J. Chem. 1997, 50 (4), 333–336. 10.1071/c96109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maximo P.; Lourenco A.; Feio S. S.; Roseiro J. C. Flavonoids from Ulex airensis and Ulex europaeus ssp. europaeus. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65 (2), 175. 10.1021/np010147j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H.; Etoh H.; Watanabe N.; Shimizu H.; Ahmad M.; Rizwani G. H.; Erysubins C.-F. Erysubins C–F, four isoflavonoids from Erythrina suberosa var. glabrescences. Phytochemistry 2001, 56 (7), 769. 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves M. P.; Cidade H.; Pinto M.; Silva A. M. S.; Gales L.; Damas A. M.; Lima R. T.; Vasconcelos M. H.; Nascimento M. D. J. Prenylated derivatives of baicalein and 3,7-dihydroxyflavone: Synthesis and study of their effects on tumor cell lines growth, cell cycle and apoptosis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46 (6), 2562–2574. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zita A.; Hermansson M. Effects of bacterial cell surface structures and hydrophobicity on attachment to activated sludge flocs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63 (3), 1168. 10.1128/aem.63.3.1168-1170.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis D.; Lauss B.; Macher-Ambrosch R.; Pfennig A.; Nidetzky B.; Kratzer R. Integration of whole-cell reaction and product isolation: Highly hydrophobic solvents promote in situ substrate supply and simplify extractive product isolation. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 257, 110–117. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.