Abstract

The prognosis of congenital heart disease (CHD) has improved, and most patients now reach adulthood. Owing to residual disease and comorbidities, it is recommended that adult CHD (ACHD) patients transition to adult care for lifelong monitoring and treatment. However, this transition period can be challenging for CHD patients owing to obstacles such as independence from their parents and establishing self-management. To achieve a seamless shift from pediatric to adult care and ensure continuity, it is important to educate and motivate patients appropriately, and an established transition system is needed that involves collaboration between CHD specialists and healthcare providers across medical specialties. The present review describes the epidemiology of ACHD and notable points in patient care as the background of transition. The concepts and an overview of transition systems, educational systems, and potential lapses in the care of their relevant causes are then provided with supporting evidence.

Keywords: adult congenital heart disease, transition, transfer, lapse in care

Introduction

The global incidence of congenital heart disease (CHD) remains at approximately 1% of all births, representing one-third of all congenital conditions. However, advances in medical care have enabled more than 90% of CHD patients to survive beyond infancy and into adulthood (1). Extracorporeal circulation has been used in surgery since the early 1950s, and individuals with CHD who underwent such procedures at that time are now in their 60s and 70s. In Japan, the population of patients with CHD has increased to 500,000, with an expected annual increase of 10,000 individuals (2). Globally, the number of adult CHD (ACHD) patients requiring hospitalization and outpatient care is on the rise (3). Heart failure (HF) patients with CHD incur higher medical costs than those without CHD (4). Furthermore, ACHD patients who are lost to follow-up for over two years are threefold more likely to require emergency surgery or catheterization than ACHD patients who are not lost to follow-up (5).

An appropriate transition from pediatric to adult care is necessary for patients with CHD, as it is for other chronic diseases in children and adolescents. Transitional care is important not only in addressing the social and economic challenges of medicine but also in shaping individual life perspectives. However, these patients and their guardians have been managing CHD, which can be life-threatening, with pediatric healthcare providers immediately after or even before birth. The transition to adult care is therefore a big deal for these individuals, and there is a risk of disengagement from the medical care itself at the time of transition/transfer. When patients are in stable health conditions without the need for urgent intervention, transition education for them and their guardians should begin in the early teens, and transfer to adult care should ideally be from the late teens to the early 20s. During this time, close connection and cooperation between pediatric and adult care members, including physicians, nurses, and coordinators, as a team with multiple perspectives is desirable.

In Japan, prefectural transition support centers for ACHD have been in place since 2018. The Japanese Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease was established as a research group in 2001 and developed into an academic society in 2010. The ACHD specialist system was created in 2019, with further strengthening of transition support on the horizon (2). The growing population of ACHD patients and the increasing diversity of diseases and comorbidities require the coordination of not only ACHD specialists but also heart surgeons, electrophysiologists, general cardiologists, and other physicians. More than ever, perspectives on trends in transitional care have become necessary for medical staff involved in ACHD care.

The present review will first describe the epidemiology of ACHD, along with important points regarding patient care as the background of the transition. We then present several key concepts on transition systems, educational systems, and overcoming potential lapses in care towards expanding ACHD transition programs worldwide.

Background of ACHD

1. Disease classification of CHD and daily care in ACHD clinics

According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, CHD is stratified according to complexity (Table 1) (6). The Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) guidelines recommend specific follow-up practices, with moderate and severe CHD patients advised to undergo regular monitoring in specialized CHD clinics (1). As of 2007, over 32% of cases in Japan were classified as moderate or higher complexity (7). For patients with simple CHD, typically under the care of a general cardiologist, timely access to a specialized CHD center is recommended when considering further interventions. Furthermore, connective tissue diseases involving large vessels, such as Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome, require regular follow-up (8).

Table 1.

Classification of Congenital Heart Disease Complexity.

| MILD: |

| Isolated congenital aortic valve disease and bicuspid aortic disease |

| Isolated congenital mitral valve disease (exce pt parachute valve, cleft leaflet) |

| Mild isolated pulmonary stenosis (infundibular, valvular, supraval vular) |

| Isolated small ASD, VSD, or PDA |

| Rep aired secundum ASD, sinus venosus defect, VSD, or PDA without residuae or sequellae, such as chamber enlargement, ventri cular dysfunction, or elevated PAP. |

| MODE RATE: (Repaired or unrepaired where not specified; alphabetical order) |

| Anomalous pulmonary venous connection (partial or total) |

| Anomalous coronary artery arising from the PA |

| Anomalous coronary artery arising from the opposite sinus |

| Aortic stenosis - subvalvular or supravalvular |

| AVSD, partial or complete, including primum AS D (excluding pulmonary vascular disease) |

| ASD secundum, moderate or large unrepaired (excluding pulmonary vascular disease) |

| Coarctation of the aorta |

| Double chambered right ventricle |

| Ebstein anomaly |

| Marfan syndrome and related HTAD, Turner Syndrome |

| PDA, moderate or large unrepaired (excluding pulmonary vascular disease) |

| Peripheral pulmonary stenosis |

| Pulmonary stenosis (infundibular, valvular, supravalvular), moderate or severe |

| Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm/fistula |

| Sinus venosus defect |

| Tetralogy of Fallot-repaired |

| Transposition of the great arteries after arterial switch operation |

| VSD with associated abn ormalities (excludin g pulmonary vascular disease) and/or moderate or greater shu nt. |

| SEVERE: (Repaired or unrepaired where not specified; alphabetical order) |

| Any CHD (repaired or unrepaired) associated with pulmonary vascular disease (including Eisenmenger syndrome) |

| Any cyanotic CHD (unoperated or palliated) |

| Double-outlet ventricle |

| Fontan circulation |

| Interrupted aortic arch |

| Pulmonary atresia (all forms) |

| Transposition of the great arteries (except for patients with arterial switch operation) |

| Univentricular heart (including double inlet left/right ventricle, tricuspid/mitral atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, any other anatomic abnormality with a functionally single ventricle) |

| Truncus arteriosus |

| Other complex abnormalities of AV and ventriculo arterial connection (i.e., crisscross heart, heterotaxy syndromes, ventricular inversion). |

ASD: atrial septal defect, AV: atrioventricular, AVSD: atrioventricular septal defect, CHD: congenital heart disease, HTAD: heritable thoracic aortic disease, LV: left ventricle/ventricular, PA: pulmonary artery, PAP: pulmonary artery pressure, PDA: patent ductus arteriosus, VSD: ventricular septal defect

Reprinted from 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (reference 6, p. 575) with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). © 2020 by the ESC.

CHD is often diagnosed from approximately 18 weeks of gestation through early childhood (9), although some forms of CHD are identified during school age or even as adults. Surgical or percutaneous interventions are performed to improve inadequate cardiac output and oxygenation as well as to optimize excessive volume and pressure load. Some treatments may be staged depending on the patient's age and degree of procedural invasiveness. Apart from surgical ligation for patent ductus arteriosus and a few other conditions, most operations for CHD are not curative but rather for repair or palliation (1). Even with optimal interventions, many patients have residual disease and may experience late complications due to sequelae and acquired comorbidities, such as hypertension, in addition to CHD. Indeed, lifelong cardiac follow-up is essential for most CHD patients (10).

The routine management of ACHD includes the evaluation of the structure and function of the ventricles, valves, and outflow tracts in addition to pulmonary hypertension (PH). Depending on the disease and history of surgical procedures, assessments should be performed for implanted shunts, diameter of the aortic root and vessels, stenosis or leakage of baffles or conduits, and failure of Fontan circulation. An example of reintervention after transition to adult care is as follows: tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is characterized by ventricular septum riding of the aorta, ventricular septal defect (VSD), hypoplasia of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), and right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy. Endocardial repair, mainly VSD closure and RVOT reconstruction, is performed during infancy. As pulmonary regurgitation (PR) can be a problem in the postoperative period, some patients with significant PR experience relatively few symptoms. Appropriate consideration of pulmonary valve replacement requires regular follow-up, including RV volume and contraction measurements by echocardiography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance, in addition to monitoring for HF and arrhythmias (1).

2. Emergencies in ACHD

Major cardiac events in patients with ACHD include arrhythmia, such as supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular arrhythmias, sick sinus syndrome, conduction disorders, HF, and sudden cardiac death (2). Infective endocarditis should also be considered, and its risk is determined according to CHD stratification (1). Patients with complex ACHD are more likely than patients with simple ACHD to have arrhythmias (11), which can be provoked by structural anomalies, intracardiac scarring from surgery, and volume and/or pressure overload. Even supraventricular tachycardia may cause hemodynamic instability and requires urgent treatment in patients with complex CHD.

HF can be exacerbated in ACHD patients due to multiple factors: 1) volume overload due to shunt or valvular insufficiency; 2) pressure overload with valvular disease or other stenotic disease; 3) ventricular dysfunction due to myocardial damage; 4) pulmonary hypertension resulting from the structural anomaly itself, ventricular dysfunction, or comorbidities such as apnea; 5) systemic hypertension and elevation of afterload caused by aortic coarctation, arteriosclerosis, hypertension, or acquired renal disease; 6) coronary artery disease; 7) cyanosis; and 8) refractory atrial arrhythmia (1).

3. Complications and comorbidities in ACHD

Managing extracardiac complications and comorbidities is an essential part of comprehensive care for ACHD. For instance, Fontan circulation is a repair technique for functional single-ventricle hemodynamics that is difficult to correct with biventricular repair. Pulmonary circulation is maintained by high central venous pressure, although there is concern about the effects of chronic venous congestion on the abdominal organs in terms of the hepatic (Fontan-associated liver disease), renal, and intestinal (protein-losing enteropathy) functions (1). In cyanotic diseases without sufficient repair and Eisenmenger syndrome, extracardiac complications may also arise, including respiratory, hematologic, hepatologic, and metabolic manifestations (12).

The extended life expectancy in CHD is also affected by lifestyle-related diseases and non-cardiac morbidities, such as malignant tumors. CHD patients with these comorbidities require consideration of each cardiac condition when treating or intervening with medication, chemotherapy, and surgery. A recent survey found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in patients with CHD than in matched controls (odds ratio: 1.8) (13). Cancers were reportedly 1.6 to 2 times more frequent in ACHD patients (median age: 44.2 years, interquartile range: 29.8-64.2) up to 10 years after survey commencement than the general population. Although some ACHD patients may have genetic backgrounds associated with cancer development, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers are the most common, as in the general population (14). Some cancers are also associated with the pathophysiology of CHD, including hepatocellular carcinoma in the Fontan circulation and neuroendocrine tumors in cyanotic CHD (15).

Regarding psychosocial comorbidities, some studies have suggested that patients with CHD experience negative consequences owing to their chronic and sometimes life-threatening conditions (16). Thus, effective transition requires not only educating patients about their CHD but also encouraging and empowering them to be able to self-manage.

Transition Process and Programs from Pediatric Care to Adult Care

1. Definition of transfer/transition in medicine

Noteworthy in transition care is the difference between the terms “transfer” and “transition”. Transfer refers to the event of connecting and changing from pediatric to adult care, with handover information provided through documents, images, and treatment plans to avoid gaps in patient management. Transition is the process by which young adults with special care needs transition from childhood to adulthood. It is a life-long and comprehensive procedure that includes preparing for the future while living with a chronic disease and educating patients and guardians. The goal of transition is to maintain or improve the survival and quality of life (QOL) of patients (17). The transition period typically occurs between 12 and 25 years old, with the recommended age for transfer between 18 and 21 years old, provided the patient is clinically stable (2).

2. The history of ACHD clinics

The first ACHD clinic was established in Toronto, Canada, in 1959, followed by Europe in 1964 (18). Currently, in many Canadian provinces and in some European countries, such as Germany, the law stipulates that patients must be transferred from pediatric clinics to adult clinics by 18 or 19 years old (19,20). Unique clinics with CHD departments providing pediatric care through adult care also exist in these countries. Of note, however, is the fact that even in these countries, the transition has not been entirely successful in many areas.

In Japan, the Japan Pediatric Society recommends that transition be based on patients and parents' will and wishes. There is no established age limitation for transfer (1); however, it should be noted that health insurance and social security systems change when a patient reaches the legal age of adulthood.

3. Education and model for transition to adult care

For children with chronic diseases, transition education should begin around 10-12 years old. Six steps of education (Got Transition Six core elements) have been recommended (Table 2) (21). Table 3 summarizes the essential components of transition education for CHD (22). At the time of transfer, it is necessary for CHD patients to understand the diagnosis of their disease, the structure of the heart, the details of surgery, medications, and the need to visit their outpatient clinic. It is especially important for pediatric patients in early elementary school grades to be able to communicate their diseases (2).

Table 2.

Key Points of Approach and Timeline for Youth with CHD in Transition Process via SIX CORE ELEMENTSTM.

| 1. | POLICY/GUIDE: Age 12-14 years |

| Develop, discuss, and share transition and care policy/guide with patients and their family. Policy means documents explaining practical methods for transition. | |

| 2. | TRACKING&MONITORING: Age 14-18 years |

| Track progress using a flow sheet registry. | |

| 3. | READINESS: Age 14-18 years |

| Start to assess self-care skills by checklists, set goals, and offer education on identified needs. | |

| 4. | PLANNING: Age 14-18 years |

| Develop a health care transition plan with medical summary. Prepare youth and parents for an adult approach to care, including legal changes in decision-making, privacy, consent, self-advocacy, and access to information. | |

| 5. | TRANSFER OF CARE: Age 18-21 years |

| Transfer to adult care when youth’s condition is as stable as possible. Complete transfer package, including final transition readiness assessment, plan of care with transition goals and prioritized actions, medical summary, and emergency care plan. | |

| Confirm the first date of appointment with adult clinic. | |

| 6. | TRANSITION COMPLETION: Age 18-23 years (18-26 years in the Japanese version) |

| Contact youth and parents 6 months after last pediatric visit. | |

| Confirm transfer completion and elicit feedback from patients. | |

| Build ongoing and collaborative partnerships with adult primary and specialty care clinicians. |

Table adapted from references 21.

Table 3.

Essential Components of a Transition Plan.

| • | Demographic information of the patient |

| • | Contact information to caregivers |

| • | Persons of importance to the adolescent |

| • | Need of special support and ongoing care |

| • | Degree of parental involvement in the transition plan/process |

| • | Brief report of current medical status |

| • | Preparations for the visit with the transition coordinator |

| • | Recommendations regarding prognosis, physical activities, drugs, family planning, endocarditis prevention, future need of interventions and follow-up, choice of profession, travelling, and driving license |

| • | Reporting of the HEADDDSS (Home, Education, Activities, Diet, Drugs, Depression, Sex, and Safety) |

| • | Goals for transition, own resources, and capacities and need of support as expressed by the patient |

| • | Reporting of accommodations designed for learning and functioning, discussed with schools and comprehensive disability services |

Reprinted from the reference 25 (p. 4,220) with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). © 2021 by the ESC.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire is used to measure the skills necessary for children with chronic diseases to transition successfully, including self-management and self-advocacy. The Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire is an assessment method dedicated to measuring knowledge of CHD (22). These tools have also been adapted, translated, and validated in Japanese according to regional characteristics (23,24).

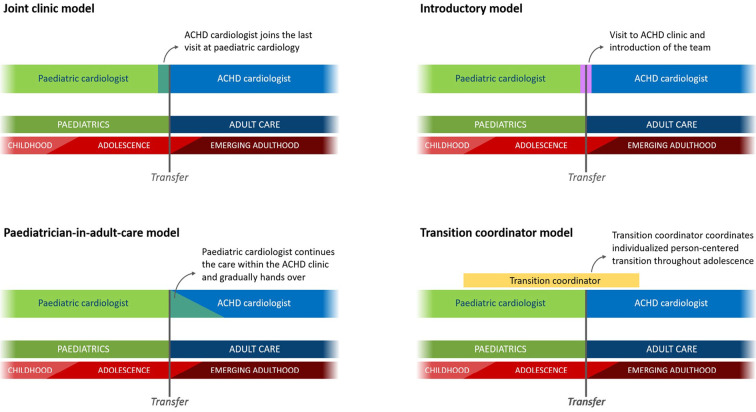

ESC guidelines define four pathways for the transition process (Figure) (25). There is a period of overlap between pediatric and adult care to reduce anxiety in patients and guardians during the transition as well as to prevent disengagement from medical care. Ideally, comprehensive education and support for patients with CHD during transitional care should be provided by a multidisciplinary team, including specialized nurses, coordinators, and psychologists. However, according to a recent report in Europe, only 4 of 96 centers met all requirements, with 60% reported as understaffed (26). Indeed, there is a need to improve transitional care teams to meet the growing demands for transitional care worldwide.

Figure.

Models for transition. Reprinted from reference 25, p. 4,218 with permission from Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). © 2021 by the ESC. The joint clinic model is currently used at the authors’ institution (Shinshu University Hospital) and partner institution. The pediatrician-in-adult-care model is also employed for complex cases and those requiring support from a pediatrician.

4. Effects of transition programs on CHD patients

Several studies have discussed the effectiveness of education programs for transition over the past decade. One study identified that the education program group (12.7%) had a lower rate of missed visits than the usual care group (36.2%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.1119) (27). Another investigation found that patients in an education group with a structured program were more health-conscious and knowledgeable about their condition and recommended follow-up than a standard care group. Furthermore, a higher percentage of female patients in the education group than the standard care group knew that their heart condition needed to be evaluated before pregnancy (28). A similar study demonstrated that transition preparation could improve disease understanding, self-efficacy, and self-management skills in CHD patients up to one year later (29). Remarkable gains related to improvements in anxiety, knowledge, life satisfaction, health awareness, and the QOL have been observed as a result of educational programs (30). Although an education program group in a previous study had a higher level of knowledge than the control group, only 11% of the patients had reached a sufficient level. Thus, it is necessary to consider more effective educational methods (31). When implementing a nurse-led transition program for adolescents with moderate or higher complexity CHD, 40% of participants required additional support for preparation (32). Furthermore, to establish structured educational programs, it is imperative to assess each patient's level of understanding and provide individualized support.

5. Barriers to transition and lapses in care

The term “lapse in care” generally refers to an interruption in medical care and not visiting an outpatient clinic for to two to three years or more. The literature on this phenomenon is influenced by multiple factors, such as the area where the study was conducted, the definition of discontinuation length, a single- or multiple-center study design, and whether or not pediatrics and adult departments were located at the same site (33). A recent meta-analysis provided data on lapses in care, with reported discontinuation rates of 34.0% in the United States, 25.7% in Canada, and 6.5% in Europe (Belgium and Sweden). As the findings from Europe included only two countries, there might be discrepancies in the actual situation across the continent (28,33). Discontinuation rates were approximately 20% in reports from both Malta and the Netherlands (34,35). Studies from the United States tended to show low transition rates, from 12% to under 30% (36,37). Since patients who were completely lost to follow-up could not be included in the discontinuation rate calculations, the number of individuals who did not receive necessary care was likely underestimated.

Table 3 outlines possible barriers to transition and continuing outpatient care (28,38-43). Evidence regarding these barriers varies by country, region, and background, including the nation's medical system and economics. The significance of being a man in discontinuation likelihood is controversial (41,42); a meta-analysis showed that the discontinuation rate was higher for men than for women. Furthermore, mild disease complexity had higher discontinuation rate (33.7%) as compared with moderate (25.7%) and severe (22.3%) complexities (27). Another study found that a history of catheterization within the previous five years and higher income were significantly related to continuing care (43). In contrast, a stable medical condition and lack of understanding about follow-up were identified as notable reasons for non-adherence, despite a high education level and understanding of the medical condition (42). The same report revealed that the distance to the clinic and disease complexity were also related to lapses in care, with the first occurrence of lapses at a mean age of 19.9 years old. As sufficient discussion the importance of adult healthcare could reduce missed visits by 70% (44), it appears essential to provide individualized guidance, especially for patients facing multiple barriers to continuity of care.

Table 4.

Potential Barriers to Transition/transfer and Continuation of Outpatient Treatment.

| ・Age, gender, race/ethnicity |

| ・Education level, income |

| ・Simple CHD, stable health condition, no medication, no recent admission or intervention |

| ・ Insufficient knowledge on CHD: name of the disease, anatomy, surgery, medication, necessity of medical care, exercise capacity, prevention for infection, etc. |

| ・Insufficient transitional care, systems, and staff including nurses and coordinators |

| ・Anxiety of patients and their guardians: differences between pediatric and adult medicine, patients making their own treatment decisions |

| ・Mental immaturity, poor self-advocacy, need for support in communication and mental status |

| ・Absence of symptoms, patient’s own belief that he/she is completely cured, young people’s sense of omnipotence |

| ・Previous history of being treated in another hospital or clinic other than CHD center |

| ・Long intervals between regular outpatient visits (>12 months) |

| ・Long distance to the hospital and relocation |

| ・Change in medical insurance/financial difficulties |

6. Exercise tolerance, employment, and family planning with ACHD

Some issues that have a major impact on a patient's life, such as employment, marriage, and pregnancy, require decisions to be made during or immediately after the transition period. However, topics associated with occupation, insurance, and family planning in patients with CHD are often discussed at 20-25 years old, despite ideally being addressed in transition programs by 16-18 years old (45).

Compared with healthy individuals, adult patients with CHD have reduced exercise tolerance, as assessed by peak oxygen consumption (VO2), even when asymptomatic. moderate CHD patients with repaired aortic coarctation or TOF showed 60-65% of peak VO2 values versus controls. severe CHD patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries or Fontan circulation exhibited roughly 40% of control values (46). Thus, depending on an individual's condition and activity level with reference to the results of an exercise stress test, patients with CHD often require restrictions or additional considerations in their daily activities.

In terms of employment, 14.6% of men and 12.5% of women among Japanese CHD patients did not have occupations, which was markedly higher than the national rates of 5.0% for men and 2.9% for women (47). According to research from Germany, there was no significant difference in the proportion of unemployment between the CHD group and controls in an initial survey. After approximately 14 years of follow-up, however, the proportion of unemployment had become significantly higher in the CHD group (7.0%) than in the control group (2.1%). CHD severity was not associated with unemployment (48).

Regarding the reproductive health of women with CHD, those who use anticoagulation drugs for mechanical valves, arrhythmia, or a single ventricle have a nearly threefold risk of menorrhagia (49). Pregnancy and delivery significantly alter the environment of the maternal body, particularly with respect to circulating blood volume, heart rate, systemic peripheral vascular resistance, and coagulability. Perinatal cardiovascular events, such as arrhythmia, HF, thrombosis, aortic dissection, and cardiac death, may occur in mothers with CHD because of greater stress than in the non-pregnant state.

Complex CHD with a high risk of maternal or neonatal events include: 1) a history of cardiac events (heart failure, transient ischemic attack, stroke, arrhythmia) and 2) severe HF (New York Heart Association Functional Classification III/IV); 3) a reduced systemic ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction <40%) and reduced subpulmonary ventricular function; 4) left heart obstruction (moderate to severe); 5) systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation (moderate to severe), pulmonary atrioventricular valve regurgitation (moderate to severe), and mechanical valve prosthesis; 6) pulmonary arterial hypertension; 7) cyanosis (O2 saturation <90%) (50). Moderate Fontan circulation [40-45 mm for Marfan syndrome and other inherited thoracic aortic diseases, 45-50 mm for bicuspid aortic valve, 20-25 mm/m2 (aortic size index) for Turner syndrome, <50 mm for TOF] or severe aortic dilatation and connective tissue diseases, such as vascular Ehlers-Danlos, were also included in the modified World Health Organization classification, which increases maternal mortality or severe morbidity (50,51). There are several representative tools for estimating the risk of maternal cardiovascular events during pregnancy based on pre-pregnancy status, including the Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG) Risk Score and Zwangerschap bij Aangeboren HARtAfwijkingen I (ZAHARA) score (51).

Reproductive health is a sensitive topic that requires genetic consideration. However, it is important for patients with CHD to obtain this information during adolescence. Preconception counseling by an obstetrician is also recommended for patients with CHD, who are at a higher risk of pregnancy and delivery than those without CHD, and their partners.

Summary

This review began with an overview of ACHD and recommended follow-up according to the disease severity. The residual conditions and comorbidities observed in adults with CHD were described, followed by the need for continuity of care. We then highlighted that transition, which is distinct from a simple change in healthcare providers, is a necessary process for the patient's future. Next, we explained that transition education programs are usually initiated for CHD patients in their early teens and outlined the elements that should be included in such endeavors. The effectiveness of education and factors that lead to withdrawal from medical care were also discussed. Surrounding these issues, topics such as employment and family planning, which greatly affect the patient health and QOL, must be addressed in the transition process.

Different countries have specific laws, healthcare systems, and insurance schemes and thus have established different policies on transition and transfer. There is also variation among facilities regarding the details of educational methods, such as program frequency and duration, making it challenging to evaluate them uniformly. Currently, there are only a few regions in the world in which sufficient human resources are available for transitional care. However, the information required for patients with CHD and their guardians in transitional care is becoming clearer and expected to spread and evolve.

Recent studies have proposed the introduction of digital healthcare for patients with CHD, including telemedicine (52), visit reminders using smartphones (37), and exercise programs using wearable devices (53). Activities are also conducted to improve self-efficacy and resilience through exercise and social participation during childhood, thereby contributing to future independence. These advances in transitional care will help establish new approaches to support the management of patients with CHD.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group . Guidelines for Management of Congenital Heart Diseases in Adults (JCS 2017) (in Japanese) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 7]. https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/JCS2017_ichida_h.pdf

- 2.Pediatrics/ACHD Committee . Statement on the healthcare transition of congenital heart disease (in Japanese) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 7]. https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ACHD_Transition_Teigen_rev3_20220426.pdf

- 3.Lee SY, Kim GB, Kwon HW, et al. Changes of hospitalization trend in the pediatric cardiology division of a single center by increasing adult with congenital heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20: 227, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burchill LJ, Gao L, Kovacs AH, et al. Hospitalization trends and health resource use for adult congenital heart disease-related heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e008775, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeung E, Kay J, Roosevelt GE, Brandon M, Yetman AT. Lapse of care as a predictor for morbidity in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 125: 62-65, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 42: 563-645, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiina Y, Toyoda T, Kawasoe Y, et al. Prevalence of adult patients with congenital heart disease in Japan. Int J Cardiol 146: 13-16, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenhoff FS, Alejo DE, Black JH, et al. Management of the aortic arch in patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 160: 1166-1175, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon-Grady AJ, Donofrio MT, Gelehrter S, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for performance of the fetal echocardiogram: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 36: 679-723, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassareo PP, Mcmahon CJ, Prendiville T, et al. Planning transition of care for adolescents affected by congenital heart disease: the Irish national pathway. Pediatr Cardiol 44: 24-33, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khairy P, Van Hare GF, Balaji S, et al. PACES/HRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Recognition and Management of Arrhythmias in Adult Congenital Heart Disease: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Heart Rhythm 11: e102-e165, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver Ruiz JM. Cardiopatías congénitas del adulto: residuos, secuelas y complicaciones de las cardiopatías congénitas operadas en la infancia [Congenital heart disease in adults: residua, sequelae, and complications of cardiac defects repaired at an early age]. Rev Esp Cardiol 56: 73-88, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deen JF, Krieger EV, Slee AE, et al. Metabolic syndrome in adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e001132, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurvitz M, Ionescu-Ittu R, Guo L, et al. Prevalence of cancer in adults with congenital heart disease compared with the general population. Am J Cardiol 118: 1742-1750, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Gurvitz MZ, Beauséjour-Ladouceur V, Lawler PR, Therrien J, Marelli AJ. Cancer risk in congenital heart disease - what is the evidence? Can J Cardiol 35: 1750-1761, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorfman TL, Archibald M, Haykowsky M, Scott SD. An examination of the psychosocial consequences experienced by children and adolescents living with congenital heart disease and their primary caregivers: a scoping review protocol. Syst Rev 12: 90, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine . A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics 110: 1304-1306, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb G, Mulder BJ, Aboulhosn J, et al. The care of adults with congenital heart disease across the globe: current assessment and future perspective: a position statement from the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Int J Cardiol 195: 326-333, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackie AS, Fournier A, Swan L, Marelli AJ, Kovacs AH. Transition and transfer from pediatric to adult congenital heart disease care in Canada: call for strategic implementation. Can J Cardiol 35: 1640-1651, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helm PC, Kaemmerer H, Breithardt G, et al. Transition in patients with congenital heart disease in Germany: results of a nationwide patient survey. Front Pediatr 5: 115, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians . Got Transition's Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0 (2018) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 7]. https://www.gottransition.org/six-core-elements/

- 22.John AS, Jackson JL, Moons P, et al.; American Heart Association Adults With congenital Heart Disease Committee of the Council on Lifelong congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young and the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Stroke Council . Advances in managing transition to adulthood for adolescents with congenital heart disease: a practical approach to transition program design: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc 11: e025278, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato Y, Ochiai R, Ishizaki Y, et al. Validation of the Japanese transition readiness assessment questionnaire. Pediatr Int 62: 221-228, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akiyama N, Ochiai R, Hokosaki T, et al. Objective and personalized assessment of disease-related knowledge among patients with congenital heart disease - development and validation of the Japanese version of the Leuven knowledge questionnaire for congenital heart disease -. Circ Rep 3: 604-614, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moons P, Bratt EL, De Backer J, et al. Transition to adulthood and transfer to adult care of adolescents with congenital heart disease: a global consensus statement of the ESC Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), the ESC Working Group on Adult Congenital Heart Disease (WG ACHD), the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), the Pan-African Society of Cardiology (PASCAR), the Asia-Pacific Pediatric Cardiac Society (APPCS), the Inter-American Society of Cardiology (IASC), the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ), the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD), the World Heart Federation (WHF), the European Congenital Heart Disease Organisation (ECHDO), and the Global Alliance for Rheumatic and Congenital Hearts (Global ARCH). Eur Heart J 42: 4213-4223, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomet C, Moons P, Budts W, et al. ; the ESC Working Group on Grown-up Congenital Heart Disease . Staffing, activities, and infrastructure in 96 specialised adult congenital heart disease clinics in Europe. Int J Cardiol 292: 100-105, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moons P, Skogby S, Bratt EL, Zühlke L, Marelli A, Goossens E. Discontinuity of cardiac follow-up in young people with congenital heart disease transitioning to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 10: e019552, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladouceur M, Calderon J, Traore M, et al. Educational needs of adolescents with congenital heart disease: impact of a transition intervention programme. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 110: 317-324, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uzark K, Yu S, Lowery R, et al. Transition readiness in teens and young adults with congenital heart disease: can we make a difference? J Pediatr 221: 201-206.e1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flocco SF, Dellafiore F, Caruso R, et al. Improving health perception through a transition care model for adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 20: 253-260, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goossens E, Van Deyk K, Zupancic N, Budts W, Moons P. Effectiveness of structured patient education on the knowledge level of adolescents and adults with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 13: 63-70, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charles S, Mackie AS, Rogers LG, et al. A typology of transition readiness for adolescents with congenital heart disease in preparation for transfer from pediatric to adult care. J Pediatr Nurs 60: 267-274, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bassareo PP, Chessa M, Di Salvo G, Walsh KP, Mcmahon CJ. Strategies to aid successful transition of adolescents with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Children (Basel) 10: 423, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caruana M, Aquilina O, Grech V. Can the inevitable be prevented? -An analysis of loss to follow-up among grown-ups with congenital heart disease in Malta. Malta Med J 30: 13-21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kollengode MS, Daniels CJ, Zaidi AN. Loss of follow-up in transition to adult CHD: a single-centre experience. Cardiol Young 28: 1001-1008, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerardin J, Raskind-Hood C, Rodriguez FH 3rd, et al. Lost in the system? Transfer to adult congenital heart disease care - challenges and solutions. Congenit Heart Dis 14: 541-548, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez KN, O'Connor M, King J, et al. Improving transitions of care for young adults with congenital heart disease: mobile app development using formative research. JMIR Form Res 2: e16, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee A, Bailey B, Cullen-Dean G, Aiello S, Morin J, Oechslin E. Transition of care in congenital heart disease: ensuring the proper handoff. Curr Cardiol Rep 19: 55, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore JA, Sheth SS, Lam WW, et al. Hope is no plan: uncovering actively missing transition-aged youth with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 43: 1046-1053, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goossens E, Fernandes SM, Landzberg MJ, Moons P. Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 116: 452-457, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kollengode MS, Daniels CJ, Zaidi AN. Loss of follow-up in transition to adult CHD: a single-centre experience. Cardiol Young 28: 1001-1008, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gurvitz M, Valente AM, Broberg C, et al.; Alliance for Adult Research in Congenital Cardiology (AARCC) and Adult Congenital Heart Association . Prevalence and predictors of gaps in care among adult congenital heart disease patients: HEART-ACHD (The Health, Education, and Access Research Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol 61: 2180-2184, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackie AS, Rempel GR, Rankin KN, Nicholas D, Magill-Evans J. Risk factors for loss to follow-up among children and young adults with congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young 22: 307-315, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko JM, Yanek LR, Cedars AM. Factors associated with a lower chance of having gaps in care in adult congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young 31: 1576-1581, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng LX, Gleason LP, Awh K, et al. Too little too late? Communication with patients with congenital heart disease about challenges of adult life. Congenit Heart Dis 14: 534-540, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, Okonko D, et al. Exercise intolerance in adult congenital heart disease: comparative severity, correlates, and prognostic implication. Circulation 112: 828-835, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enomoto J, Mizuno Y, Okajima Y, Kawasoe Y, Morishima H, Tateno S. Employment status and contributing factors among adults with congenital heart disease in Japan. Pediatr Int 62: 390-398, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geyer S, Fleig K, Norozi K, et al. Life chances after surgery of congenital heart disease: a case-control-study of inter- and intragenerational social mobility over 15 years. PLoS One 16: e0246169, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haberer K, Silversides CK. Congenital heart disease and women's health across the life span: focus on reproductive issues. Can J Cardiol 35: 1652-1663, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 39: 3165-3241, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group . Guideline on Indication and Management of Pregnancy and Delivery in Women with Heart Disease (JCS 2018) [in Japanese] [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/JCS2018_akagi_ikeda.pdf

- 52.Borrelli N, Grimaldi N, Papaccioli G, Fusco F, Palma M, Sarubbi B. Telemedicine in adult congenital heart disease: usefulness of digital health technology in the assistance of critical patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20: 5775, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willinger L, Oberhoffer-Fritz R, Ewert P, Müller J. Digital Health Nudging to increase physical activity in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J 262: 1-9, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]