Abstract

Objectives

Evaluate the surgical results of cerebellopontine angle (CPA) meningiomas via a retrosigmoid approach.

Methods

This study investigated the outcomes of the retrosigmoid approach for CPA meningiomas in 36 patients. Demographic characteristics and surgical outcomes were recorded on admission, post-operation for 3-month, and 12-month follow-up. Surgical outcome was measured by using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), the extent of resection (EOR), and cranial nerve functions. Statistical analysis was conducted to identify the factors influencing outcomes.

Results

The data showed 69.4 % of the patients had a tumor with a size over 30 mm. Intraoperatively, the most common site of dural attachment was supra-meatal (33.3 %) and only one patient had a tumor centered on internal acoustic meatus (IAM). Gross total resection was achieved in 25 patients (69.4 %). Good functional status (GOS 4–5) at discharge was 77.8 % and at 12-month follow-up was 88.9 %. Large tumors (>30 mm) with brainstem compression, brainstem edema, flow-void within tumor, and invasion of cranial foramina (Meckel's cave, jugular foramen) significantly impacted the outcome (p < 0.05). Tumors invading the IAM were associated with a significantly higher risk of facial palsy compared to those without IAM involvement. Besides, aspiration pneumonia was strongly related to poor outcomes (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Most CPA meningiomas can safely be resected via a retrosigmoid approach, highlighting the importance of meticulous surgical technique and post-operative care. However, careful consideration of factors like tumor size, flow-void within tumor, brainstem compression, brainstem edema, and potential complications (due to invasion of cranial foramina) can help optimize surgical strategy and improve long-term functional outcomes.

Keywords: CPA meningiomas, Retrosigmoid approach, Surgical outcomes

Highlights

-

•

Surgical outcome of cerebellopontine angle meningiomas via a retrosigmoid approach.

-

•

Factors impacting outcomes.

-

•

Complications following CPA meningiomas resection.

1. Introduction

Meningiomas were first described by Felix Plater in 1614, and Harvey Cushing later used the term "meningioma" to describe this type of tumor of the central nervous system [1]. Regarding posterior fossa meningiomas, Castellano and Ruggiero classified them into five groups, in which meningiomas of the posterior petrous bone are the most common (42 %) [2]. These slow-growing lesions often reach large size, compressing neural structures such as the brainstem, cerebellum, and cranial nerves from V to VII/VIII and IX/X/XI. Despite advancements in surgery, CPA meningiomas remain one of the most difficult tumors in skull base surgery, requiring surgeons with knowledge and experience in this field.

The retrosigmoid approach is routinely used for lesions in CPA angle. The advantages include a wide working angle, less structural damage, preserving hearing, and being familiar with neurosurgeons. However, this is a challenging tumor location even for experienced surgeons. Considering the low-budget setting plus the newly established neurosurgical society of Vietnam, we conducted the study "Surgical outcome of CPA meningiomas via a retrosigmoid approach: a single-center experience in Vietnam".

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, setting, and participant

A retrospective analysis was conducted to evaluate the surgical outcome of CPA meningiomas. All operation was performed at the operating theatre at University Medical Center, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. From November 2019 to December 2022, a cohort of thirty-six patients were enrolled based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows.

-

-

Age >18 years

-

-

Meningiomas have a dural tail attached to the posterior petrous bone

-

-

There are indications for surgery

-

-

Via a retrosigmoid approach

-

-

Pathological indicated meningiomas

2.2. Neuroradiological and pre-operational data

MRI data were obtained including tumor size (largest diameter), the site of dural attachment, and the invasion of the tumor into cranial foramina (Meckel's cave, IAM, jugular foramen). Other findings such as compression of cerebellum/brainstem, brainstem/cerebellar edema, hydrocephalus, and flow-void inside tumor were also collected.

2.3. Intra-operative data

Neurosurgeon identified the site of dura attachment relative to IAM to determine its location. Five categories were used: pre-meatal, retro-meatal, supra-meatal, intra-meatal, and centered on the IAM. Meningioma consistency grading scale includes soft, average, and firm/calcified [3].

The extent of resection was determined by a postoperative MRI scan at a 3-month follow-up and categorized as gross-total resection (GTR; Simpson grades I-II), near-total resection (NTR; residual tumor diameter <1 cm on post-operative contrast-enhanced CT/MRI; Simpson grade III), or partial resection (PR; residual tumor diameter >1 cm on post-operative contrast-enhanced CT/MRI; Simpson grades IV-V).

2.4. Outcome measurements

Surgical outcomes were assessed using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), where good outcome was defined as GOS 4 or 5, and poor outcomes as GOS 1, 2, or 3. Post-operative clinical examination identified any injured cranial nerves, such as impaired eye movement, new numbness/facial sensation loss, or swallowing difficulties (identified by laryngoscopy showing poor vocal cord mobility or paralysis). Surgical complications included meningitis, surgical site infection, and postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.

Facial palsy was based on the House-Brackmann scale, into 3 groups.

-

-

No palsy: House-Brackmann grade 1.

-

-

Mild palsy: House-Brackmann grade 2 and 3.

-

-

Severe palsy: House-Brackmann grade 4, 5, 6.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile frequency, and percentage were used to describe the data. Chi-squared tests, Fisher's exact tests, and Paired-Sample T-tests were used to evaluate the association between patient characteristics and GOS score. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 25.0 software.

2.6. Ethics statement

The Ethics Committee of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City approved our research project (no. 555/HĐĐĐ-ĐHYD). All procedures followed the national ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. All participants read the participation information sheet and signed the consent form.

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ characteristics

In 36 cases of CPA meningiomas, there were 33 women, and a female/male ratio = 11/1. The mean age was 55.5 years, ranging from 36 to 69 years old. The age group with the highest percentage was 45–60 years old, accounting for 55.6 %. MRI scans showed that the tumors had large size at the time of surgery, with an average diameter of 37 ± 12 mm, ranging from 16 mm to 62 mm. The percentage of large tumors (>30 mm) was 69.4 %.

The most commonly compressed brain structures are pons and cerebellum at 69.4 % and 75 %, respectively. One-third of prolonged compression led to brainstem edema and cerebellar edema. Obstructed hydrocephalus was 11.1 % (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre- and intraoperative patient characteristics.

| Pre-operation data | Number of patients (n%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (8.3) |

| Female | 33 (91.7) |

| Age | 55.5 ± 8.8 y.o |

| Under 45 y.o | 4 (11.1) |

| From 45 to 60 y.o | 20 (55.6) |

| Above 60 y.o | 12 (33.3) |

| Diameter of tumors ≥30 mm | 25 (69.4) |

| Flow-void inside tumor on MRI | 7 (19.4) |

| Hyper-intensity on T2-weighted MRI | 13 (36.1) |

| Tumor invasion | |

| Meckel's cave | 14 (38.9) |

| IAM | 21 (58.3) |

| Jugular foramen | 12 (33.3) |

| Foramen magnum | 2 (5.6) |

| Brainstem compression | 25 (69.4) |

| Brainstem edema | 12 (33.3) |

| Cerebellar compression | 27 (75) |

| Cerebellar edema | 13 (36.1) |

| Intra-operation data | |

| Tumor consistency | |

| Soft | 15 (41.7) |

| Average | 10 (27.8) |

| Calcified | 11 (30.6) |

| Extent of resection | |

| Gross total | 25 (69.4) |

| Near total | 7 (19.4) |

| Partial resection | 4 (11.2) |

| Site of dural attachment | |

| Supra-meatal | 12 (33.3) |

| Pre-meatal | 12 (33.3) |

| Retro-meatal | 7 (19.5) |

| Infra-meatal | 4 (11.1) |

| Centered on IAM | 1 (2.8) |

Abbreviation: y.o – years old.

Most cases of CPA meningiomas have signs of dura tail on MRI-enhanced and spread in many directions on the posterior petrous bone. The most common site of invasion was IAM with 58.3 %. Tumors can also spread to Meckel's fossa, jugular foramen or magnum foramen (Table 1).

Intraoperatively, Table 1 shows the site of dural attachment relative to IAM: supra-meatal (33.3 %), pre-meatal (33.3 %), followed by retro-meatal (19.5 %), infra-meatal (11.1 %) and centered at IAM (2.8 %). Tumor consistency was recorded as soft, average, and calcified, accounting for 41.7 %, 27.8 %, and 30.6 %, respectively.

Displacement of cranial nerves corresponding to tumor location was also documented and illustrated in Table 4 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4.

Table 4.

Displacement of cranial nerves relative to tumor locations.

| Tumor location | Pre meatal | Supra meatal | Retro meatal | Infra meatal | Centered on IAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN V | ant (6) sup (3) unrelated (3) |

ant (10) unrelated (2) |

ant (1) unrelated (6) |

Unrelated (4) | Ant (1) |

| CN VII, VIII | pst (7) inf (2) unrelated (3) |

pst (2) inf (10) unrelated (0) |

ant (6) unrelated (1) |

ant (2) sup (2) |

ant (1) |

| CN IX, X | inf (6) unrelated (6) |

inf (7) unrelated (5) |

inf (5) unrelated (2) |

inf (3) unrelated (1) |

inf (1) |

Abbreviation: ant – anterior; sup – superior; pst – posterior; inf - inferior.

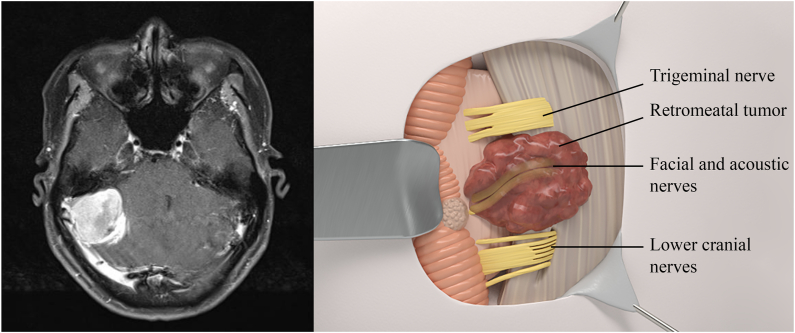

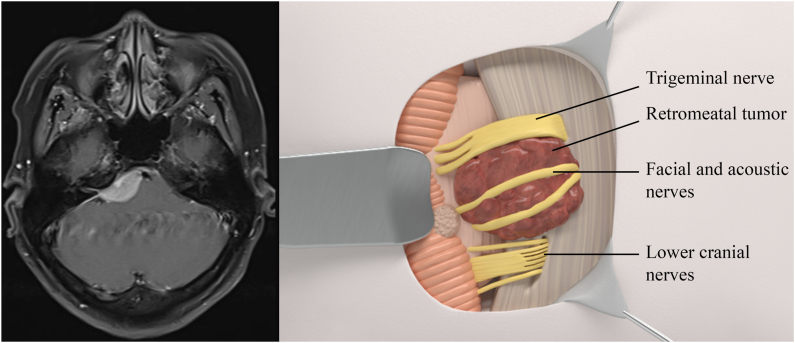

Fig. 1.

Left: MRI scan of retrometal meningioma. Right: Relationship of cranial nerves to retrometal meningioma using 3D illustration.

Fig. 2.

Left: MRI scan of premetal meningioma. Right: Relationship of cranial nerves to premetal meningioma using 3D illustration.

Fig. 3.

Left: MRI scan of inframetal meningioma. Right: Relationship of cranial nerves to inframetal meningioma using 3D illustration.

Fig. 4.

Left: MRI scan of suprametal meningioma. Right: Relationship of cranial nerves to suprametal meningioma using 3D illustration.

3.2. Surgical outcome

Following hospital discharge, a high proportion of patients (77.8 %) achieved good outcomes (GOS 4–5). Severe facial palsy and hemiparesis found post-op account for 19.4 % and 25 %, respectively. Among the patients, vertigo was common (45.5 %). Only four patients suffered meningitis and were successfully treated. Besides, dysphagia was identified in 7 patients who needed a feeding tube during hospital stay. Three patients suffered aspiration pneumonia and two of them died due to severe infection (Table 2).

Table 2.

Surgical results of 36 patients via retrosigmoid approach.

| Post-operative data | Number of patients (n%) |

|---|---|

| Impaired eye movement | 5 (15.2) |

| Numbness/loss of facial sensation | 5 (15.2) |

| Facial palsy | |

| No palsy | 17 (51.5) |

| Mild | 9 (27.3) |

| Severe | 7 (21.2) |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 3 (9.1) |

| Dysphagia | 7 (21.2) |

| Vertigo | 15 (45.5) |

| Ataxia | 10 (30.3) |

| Meningitis | 4 (12.1) |

| Muscle strength | |

| 5/5 | 24 (72.7) |

| 3/5–4/5 | 4 (12.2) |

| 0–2/5 | 5 (15.1) |

| GOS at discharge | |

| 1 | 1 (2.8) |

| 2 | 1 (2.8) |

| 3 | 6 (16.7) |

| 4 | 6 (16.7) |

| 5 | 22 (61.1) |

| GOS at 12-month | |

| 1 | 2 (5.6) |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 (5.6) |

| 4 | 4 (11.1) |

| 5 | 28 (77.7) |

At 3-month follow-up, MRI scans showed that gross total resection was achieved in 25 patients. At 12-month follow-up, 88.9 % of the patients achieve good functional status.

3.3. Factors affecting outcome

Regarding the location of tumors and tumor consistency, our findings marked no statistical difference between groups of good and poor outcomes. However, large tumors with the invasion of Meckel's cave or jugular foramen had lower GOS than tumors without (p < 0.05). In addition, small tumors without flow-void, without brainstem compression, and without brainstem edema had significantly better discharge conditions (p < 0.05). Table 3 shows all factors impacting outcomes in our study.

Table 3.

Factors affecting outcomes.

| Factors | GOS 4–5 n (%) | GOS 1–3 n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of tumors | ||||

| ≥ 30 mm | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | 0.03 | |

| < 30 mm | 11 (100) | 0 | ||

| Flow-void within tumor on MRI | ||||

| Yes | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 0.01 | |

| No | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Invade Meckel's cave | ||||

| Yes | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) | 0.02 | |

| No | 20 (90.9) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Invade jugular foramen | ||||

| Yes | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 0.05 | |

| No | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | ||

| Brainstem compression | ||||

| Yes | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | 0.03 | |

| No | 11 (100) | 0 | ||

| Brainstem edema | ||||

| Yes | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 0.05 | |

| No | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | ||

| Aspiration pneumonia | ||||

| Yes | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0.05 | |

| No | 27 (81.8) | 6 (18.2) | ||

| Post-op CT scan | ||||

| No significant brain contusion | 25 (92.6) | 2 (7.4) | 0.001 | |

| Brain contusion/hematoma | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | ||

| Post-op hydrocephalus | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Aspiration pneumonia | ||||

| Invade foramen magnum | Yes | No | ||

| Yes | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 0.03 | |

| No | 1 (4.2) | 23 (95.8) | ||

| Injuries of the lower cranial nerves | ||||

| Yes | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.03 | |

| No | 1 (3.4) | 28 (96.6) | ||

| Post-op vertigo | ||||

| Yes | 3 (20) | 12 (80) | 0.03 | |

| No | 0 | 21 (100) | ||

| Facial palsy | ||||

| Invade IAM | No | Mild | Severe | |

| Yes | 5 (23.8) | 8 (38.1) | 8 (38.1) | 0.04 |

| No | 2 (13.3) | 12 (80) | 1 (6.7) | |

Regarding cranial nerve function in Table 3, facial palsy post-op had a significantly higher percentage in group of IAM invasion than tumors without IAM invasion (p < 0.05). Besides, aspiration pneumonia was significantly related to poor GOS, and the incidence of this complication was statistical difference in patients with tumors invading foramen magnum, with injuries to lower cranial nerves, and with vertigo.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Vietnamese demographic data of CPA meningiomas

Most of the patients in our study are middle-aged females and the female: male ratio is 11:1. Our result is similar to previous studies in that female patients have a higher incidence than male patients. The average age of meningiomas is between 40 and 60 years old, and women have twice the rate of men [4]. On the one hand, the differences could be attributed to the effect of hormones as well as hormone replacement during menopause [4]. However, there is not enough evidence to support this hypothesis. On the other hand, our data probably suggests a cultural tendency in which Vietnamese women would sooner seek healthcare than Vietnamese men.

In a limiting-resource setting, a great number of patients are generally hesitant to seek medical attention with mild symptoms. As a result, most of the tumors are lately diagnosed, have large size (>3 cm, 69.4 %), and compress neural structures in the posterior fossa. One-third of the cases also exhibited peritumoral cerebral edema, indicating the loss of leptomeningeal blood supply. Peritumoral edema suggests the pia mater has been damaged and the potential difficulty of resection due to tumor coherence. Moreover, flow void within a tumor demonstrates vessels encaged by tumor, which further complicates a challenging case. Thereby, a neurosurgeon must have an overview and then optimize surgery strategies.

Another notable point of view of Vietnamese patients, after surgery, they are not always adherent to follow-up. As a result, the follow-up period was relatively short compared to other studies. To address this challenge, we use Gamma Knife radiosurgery to achieve tumor control, despite limited long-term follow-up.

4.2. CPA meningiomas via a retrosigmoid approach

To access lesions in the cerebellopontine angle, neurosurgeons can consider retrosigmoid approach, suboccipital approach, retro-labyrinthine or trans-labyrinthine approach, and anterior petrosal approach. The retrosigmoid approach, however, has been widely used thanks to several notable advantages. First, it is a familiar approach for all neurosurgeons with a simple craniotomy technique, reducing operating time. Second, it is the shortest pathway to access all lesions in the cerebellopontine angle area. Third, it is capable of preserving hearing, sparing the destructive bone drilling. After opening the dura mater, the neurosurgeon sucks CSF at CPA cistern, cerebellomedullary cistern, and magna cisterna. When CSF is drained, the brain becomes relaxed and the cerebellum can be lifted to reveal the site of dural attachment, providing a large working space from the tentorium to even the foramen magnum.

However, retrosigmoid approach also has some disadvantages. Notably, achieving Simpson I is difficult, especially for deep tumors. For example, the GTR in our study is 69.4 % and lower than other authors: Samii reported the rate of complete tumor removal according to (Simpson 1) up to 86 %, Bassiouni 84.3 %. First, our philosophy that radical tumor resection is not always plausible when GTR possibly damages important vascular and neural structures, especially in the era of gamma knife radiosurgery [5]. We leave residual tumors in Meckel's cave, IAM, and jugular foramen. On the other hand, in case of vascular structure encaged by a tumor, we leave a thin tumor layer to avoid damage. Other authors made the same decision in difficult cases [6]. Through a follow-up period of 12 months, the longest being 36 months, no tumor recurrence was recorded in our study.

4.3. Sub-groups of CPA meningiomas

In our study, we grouped CPA meningiomas into 5 groups relative to the IAM intraoperatively. Each group has several different characteristics due to different growth directions, compressing the vascular nerve structures in many different ways, so the surgical approach will be different in each subgroup.

Retromeatal meningiomas (Fig. 1) are relatively safer to resection than other groups of CPA meningiomas thanks to the tumor being superficial, involving mostly the cerebellum. Cranial nerves are pushed anteriorly and inferiorly. More specifically, the VII/VIII complexes are pushed anteriorly (85 %) or inferiorly (15 %). The lower cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and PICA are pushed inferiorly. In addition, the site of dural attachment is between the IAM and the sigmoid sinus. As a result, devascularization and debulking were more favorable.

Premeatal meningiomas (Fig. 2) can invade the Meckel fossa, and even extend to clivus. The trigeminal nerve is often pushed anteriorly (50 %), superiorly (25 %), or not involved (25 %). The VII/VIII complexes are often pushed posteriorly (58.3 %) or not involved (25 %). Large tumors can push the basilar artery medially. This is a deep location with a narrow surgical field. Devascularizing the dural attachment may be difficult due to brain swelling as well as a narrow working space, hindered by VII/VIII nerves being pushed posteriorly.

Inframeatal meningiomas (Fig. 3) can cause VII/VIII nerves to be pushed superiorly (50 %) and anteriorly (50 %). The tumor may intrude into the jugular foramen. The lower cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and PICA are pushed inferiorly and may be encaged by tumor.

Supramental meningiomas (Fig. 4) locate between IAM and tentorium. The VII/VIII complexes are often pushed inferiorly (83.3 %) and may be encaged by the tumor. Devascularization is quite difficult due to high location, requiring a slight change in positioning: the top of the head is slightly bent toward the floor, creating a 15-degree angle, widening the surgeon's viewing angle toward the tentorium.

As regards tumors centered on IAM, it is still unclear why some tumors tend to grow into the IAM while others develop completely into the CPA cisterna. Statistics show that about 10 % of primary tumors originate in the IAM and gradually spread into the CPA, with images similar to schwannoma of the acoustic nerve. The question is whether it is necessary to open the IAM to get the full exposure. Some authors suggest that, if the patient has no symptoms related to the VII or VIII nerves before surgery, drilling the IAM to remove the entire tumor is not necessary because it may cause new symptoms post-op. In addition, tumors that invade the IAM are sometimes very attached to the auditory nerve and facial nerve, so GTR can lead to permanent nerve damage. Some authors do not support drilling the IAM to achieve GTR, instead leaving a small part if the tumor is considered coherent and difficult to remove [7]. These tumors will then be subjected to Gamma knife radiosurgery.

4.4. Surgical results according to the GOS score

Most of our patients were discharged from our hospital, however, there was 1 patient in coma post-op (2.8 %) and 1 patient died due to aspiration pneumonia (2.8 %). The proportion of patients with good GOS (4–5) accounted for 77.8 % at discharge. The average follow-up time in our study is 14 ± 3 months, from 12 months to 36 months. All patients had neurological examinations and brain MRI check-ups at 3 months and 12 months after surgery. The percentage of GOS 4–5 after 1 year increased to 88.8 % after 12 months and no tumor recurrence was recorded after 12 months. Most of the patients well recovered because surgical resection offered decompression of brainstem and removal of factors that cause edema, thereby facilitating the recovery of nervous system function.

Complications mainly related to the cranial nerves, especially the VII/VIII complexes were the most damaged. Other complications related to the surgery include acute post-operative hydrocephalus, CSF leak, meningitis, and aspiration pneumonia, accounting for a small percentage, but greatly affecting the outcome of surgery. In our study, 3 patients suffered aspiration pneumonia and two of them died due to severe infection.

4.5. Factors affecting outcomes

Notably, our findings demonstrated that tumor location and tumor consistency did not influence outcomes. Other factors such as compression of the brainstem, large size, and flow-void within tumor define a challenging case. In the group with these unfavorable factors, GOS was lower than in the group without brainstem compression, small size, and soft (p < 0.05). Facing these large and deep tumors requires surgeons to debulk in a deep surgical field as well as gentle brain retraction to avoid injuries to cranial nerves and cerebellum.

In addition, our study also shows that brainstem edema recorded on pre-op MRI has lower GOS than without brainstem edema (p < 0.05). Buhl and colleagues studied 66 meningioma patients and concluded that small tumors and little brain edema around the tumor were favorable factors for good surgical results [8]. The larger the tumor, the greater the level of compression, which led to insufficient blood supply and caused edema due to cytotoxicity. This physiology is related to the destruction of the arachnoid layer, losing the dissection plane between the tumor and the brain parenchyma, and even tightly coherent to the brain surface, thereby, difficulty in dissection.

Post-op facial nerve palsy is marginally related to the tumor location (p < 0.07), especially in tumor-intruding IAM (p < 0.03). Our findings also show that tumor size does not affect facial palsy, which is similar to the Nakamura study [9]. In addition, regarding tumor consistency, at the time of surgery, in cases of soft tumors, the arachnoid layer still separates the tumor and the cranial nerves. We performed debulking tumors as much as possible. In the case of calcified tumors, the VII/VIII nerves encaged by tumors, we proactively leave a small part in the IAM.

The mortality and disability rates in the management of CPA meningiomas are very low, however, these poor outcomes are related to injuries of the lower cranial nerves leading to aspiration pneumonia and postoperative respiratory failure [[10], [11], [12]]. Most patients require airway protection, aspiration avoidance, and postoperative speech therapy [13]. In our study, the patients with jugular foramen invasion were intubated and had a nasogastric tube placed. When the patient is fully awake, swallowing status is carefully evaluated by a physical therapist. There were 3 severe cases, aspiration pneumonia, requiring tracheostomy (1 recovered, 2 died). Author Mario Sanna believes that all cases of low cranial nerve paralysis can recover well after surgery, so proactively removing the tumor thoroughly, including dissection and devascularizing the dural attachment reduces the recurrence rate [13]. However, in our opinion, radical removal of Simpson I tumor is not necessary, and preserving lower cranial nerve function is vital because low cranial paralysis is mainly related to postoperative mortality as mentioned above, and more importantly, we have another means of post-operative support treatment whose effectiveness has been proven: gamma knife radiosurgery.

5. Conclusion

Most CPA meningiomas can safely be resected via a retrosigmoid approach, highlighting the importance of meticulous surgical technique and post-operative care. However, careful consideration of factors like tumor size, flow-void within tumor, brainstem compression, brainstem edema, and potential complications (due to invasion of cranial foramina) can help optimize surgical strategy and improve long-term functional outcomes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hong-Hai Do: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Luan Trung Nguyen Dao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Minh-Anh Nguyen: Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Thanh-Lam Nguyen: Methodology, Investigation.

Previous presentations

No.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Thank Kieu-Trinh Nguyen who illustrated the 3D figures of tumors.

References

- 1.Cushing H. The meningiomas (Dural endotheliomas): their source, and favoured seats of origin. Brain. 1922;45(2):282–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggiero G., Castellano F. Upward displacement of the posterior part of the third ventricle; a method for its evaluation. Acta radiologica. 1953;39(5):377–384. doi: 10.3109/00016925309136723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itamura K., Chang K.E., Lucas J., Donoho D.A., Giannotta S., Zada G. Prospective clinical validation of a meningioma consistency grading scheme: association with surgical outcomes and extent of tumor resection. J. Neurosurg. 2018:1–5. doi: 10.3171/2018.7.JNS1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockhill J., Mrugala M., Chamberlain M.C. Intracranial meningiomas: an overview of diagnosis and treatment %J. Neurosurgical Focus FOC. 2007;23(4):E1. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/10/E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roser F., Nakamura M., Dormiani M., Matthies C., Vorkapic P., Samii M. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle with extension into the internal auditory canal. J Journal of Neurosurgery. 2005;102(1):17–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.1.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyre M., Bozorg-Grayeli A., Rey A., Sterkers O., Kalamarides M. Posterior petrous bone meningiomas: surgical experience in 53 patients and literature review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2012;35(1):53–66. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassiouni H., Hunold A., Asgari S., Stolke D. Meningiomas of the posterior petrous bone: functional outcome after microsurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100(6):1014–1024. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buhl R., Hasan A., Behnke A., Mehdorn H.M. Results in the operative treatment of elderly patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurg. Rev. 2000;23(1):25–29. doi: 10.1007/s101430050027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura M., Roser F., Dormiani M., Matthies C., Vorkapic P., Samii M. Facial and cochlear nerve function after surgery of cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:77–90. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000154699.29796.34. ; discussion 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane A.J., Sughrue M.E., Rutkowski M.J., Berger M.S., McDermott M.W., Parsa A.T. Clinical and surgical considerations for cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. J. Clin. Neurosci.: official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2011;18(6):755–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roser F., Nakamura M., Dormiani M., Matthies C., Vorkapic P., Samii M. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle with extension into the internal auditory canal. J. Neurosurg. 2005;102(1):17–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.1.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon N., Shah A., Couldwell W.T., Kalani M.Y.S., Park M.S. Preoperative embolization of skull base meningiomas: current indications, techniques, and pearls for complication avoidance. Neurosurg. Focus. 2018;44(4) doi: 10.3171/2018.1.FOCUS17686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanna M., Bacciu A., Falcioni M., Taibah A., Piazza P. Surgical management of jugular foramen meningiomas: a series of 13 cases and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(10):1710–1719. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180cc20a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]