Abstract

Introduction

By 2019, nearly 20 million people worldwide had hypertensive heart disease (HHD), resulting in over 1.1 million deaths and 21.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Hypertension is a significant factor in heart failure (HF), contributing to about a quarter of cases, increasing to 68 % in older adults. This study examines mortality trends among patients in the United States (US) affected by HHD and HF.

Methodology

This study used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) data from 1999 to 2020 to analyze deaths in the United States among adults aged 25 and older from HHD and (congestive) HF (ICD-10 code I11.0). Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) and annual percent change (APC) were calculated by year, sex, age groups, race/ethnicity, geographics, and urbanization status.

Results

Between 1999 and 2020, AAMRs increased from 3.7 to 13.5 per 100,000 population, with a steep increase from 2014 to 2020 (APC: 14.44; 95 % CI: 11.12 to 20.62). Men had slightly higher AAMRs than women (6.3 vs. 6.1). Additionally, AAMRs were highest among non-Hispanic (NH) Black individuals. Non-metropolitan areas had higher AAMRs than metropolitan areas (6.6 vs 6.2). The average AAMR during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) was nearly three times the pre-pandemic average (1999–2019).

Conclusions

Mortality from combined HHD and HF has risen since 1999, with higher rates among men, NH Black individuals, and those in non-metropolitan areas. Policy changes are needed to address these disparities and enhance healthcare equity.

Keywords: Mortality, Heart failure, Hypertension, Heart disease, Epidemiology, Trends, Racial disparity, Sex disparity, Cardiology

Highlights

-

•

From 1999 to 2020, U.S. AAMRs for hypertensive heart disease with heart failure surged, notably after 2014.

-

•

Non-Hispanic Black individuals, men, and non-metropolitan residents had the highest mortality rates.

-

•

Findings highlight the need for targeted policies to reduce disparities and improve healthcare equity in HHD with CHF.

Abbreviations

- (APC)

Annual percentage change

- (AAMR)

Age-adjusted mortality rates

- (HF)

Heart failure

- (HHD)

Hypertensive heart disease

- (CVD)

Cardiovascular disease

- (NH)

Non-Hispanic

- (CDC WONDER)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research

1. Introduction

According to the Global Health Observatory, approximately 12.8 % of deaths worldwide are caused by hypertension [1]. Hypertension is a powerful indicator of heart failure (HF) and is currently classified as the second leading cause of HF [2]. Notably, the Framingham Heart Study identified hypertension as a precursor in 91 % of HF cases during a 20-year follow-up period [3]. Another study demonstrated that individuals without hypertension and its associated risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes, tended to live 3–15 years free from HF compared to those with hypertension [4].

Prolonged hypertension triggers ventricular hypertrophy, culminating in both HF with preserved ejection fraction and HF with reduced ejection fraction [5,6], resulting in the pathological state of hypertensive heart disease (HHD). The Global Burden of Disease 2019 study reported a staggering 1.16 million deaths attributable to HHD globally, with projections indicating a distressing rise to 1.57 million deaths by 2034 [7]. Common etiological factors for HHD include aging, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity, which lead to both systemic and pulmonary manifestations of HHD [[8], [9], [10]]. Ironically, although hypertension precedes HHD, it paradoxically remains the most modifiable risk factor for HF development.

As the burden of HHD-related HF grows, addressing its clinical, economic, and societal impacts becomes paramount. Though the introduction of novel therapies and updated guidelines significantly influenced the life expectancy of individuals affected by these conditions, there is still a gap in research about trends and disparities in mortality due to HHD associated with HF, which our study aims to bridge.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study setting and population

We sourced mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) Database. Using this resource, we applied the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code I11.0 for "hypertensive heart disease with (congestive) heart failure" [11]. Our analysis centered on death certificates within the Multiple Cause of Death Public Use dataset, allowing us to explore the mortality associated with these conditions in patients aged ≥25 years. Institutional review board approval was unnecessary, as we utilized a de-identified government-provided public-use dataset per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [12].

2.2. Data abstraction

Our analysis involved stratifying data based on abstracted demographic variables, including population size, age distribution, sex, racial/ethnic background, geographic location, urbanization level, and place of death. The locations of death encompassed diverse settings: inpatient facilities, outpatient clinics, emergency rooms, cases of sudden death, residences, hospice/nursing homes, long-term care facilities, and instances where the location remained unspecified. Racial and ethnic categories were meticulously defined, including Hispanic (Latino), non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, NH American Indian/Alaskan Native, and NH Asian.

Furthermore, we categorized the patients into ten-year intervals, distinguishing young adults (25–44 years), middle-aged adults (45–64 years), and older individuals (65–85+ years) [13]. Geographically, we employed the Urban-Rural Classification Scheme of the National Center for Health Statistics to classify our study population. Urban areas housed populations of 50,000 or more, whereas rural regions encompassed locales with fewer than 50,000 residents. Additionally, we divided the United States into four regions based on the US Census Bureau's classification: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West [14].

2.3. Statistical analysis

We systematically examined sex, race/ethnicity, age, urbanization, and census-related patterns by computing age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) per 100,000 individuals. The 2000 US population served as the baseline for AAMR standardization. To assess temporal changes in mortality rates, we employed the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 5.0.2; National Cancer Institute) [15]. This analytical approach involved fitting log-linear regression models to crude data trends, enabling us to calculate the annual percentage change (APC) in AAMR and its 95 % confidence interval (CI). To classify the APCs as increasing or decreasing, we rigorously evaluated their statistical deviation from the null hypothesis of zero change. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t-test with a threshold of p < 0.05. To assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality trends, a separate analysis was conducted using data from the pandemic years (2020–2022). Additionally, the average AAMR prior to the pandemic (1999–2019) was compared with that during the pandemic (2020–2022).

3. Results

Between 1999 and 2020, 302,270 deaths occurred, where HHD with HF was either the underlying or contributing cause (Supplemental Table 1). The place of death was recorded for 284,739 cases: 34.7 % in decedents’ homes, 30 % in nursing home/long-term facilities, 25.1 % in medical facilities, and 4.4 % in hospices.(Supplemental Table 2).

3.1. Demographic trends in mortality

The AAMR was 3.7 (95 % CI: 3.6–3.8) 1999 and rose to 13.5 (95 % CI: 13.4–13.6) in 2020. The overall AAMR significantly decreased from 1999 to 2004 (APC: 7.98; 95 % CI: 23.41 to −0.58) and then increased substantially from 2004 to 2007 (APC: 42.72; 95 % CI: 21.70 to 57.57). It slightly decreased from 2007 to 2014 (APC: 0.97; 95 % CI: 9.55 to 2.10) and sharply increased from 2014 to 2020 (APC: 14.44; 95 % CI: 11.12 to 20.62) (Fig. 1, Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Fig. 1.

Overall and sex-stratified hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000 in adults in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

∗ Indicates that the annual percentage change (APC) is significantly different from zero at α = 0.05. AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate.

3.2. Sex stratification

During the study period, men's AAMRs were comparable to women's (Men: 6.3; 95 % CI: 6.3–6.4; Women: 6.1; 95 % CI: 6.0–6.1). In 1999, the average AAMR for men was 3.1 (95 % CI: 2.9–3.2), which decreased significantly to 2.3 (95 % CI: 2.2–2.4) in 2003 (APC: 11.64; 95 % CI: 33.99 to −1.85). It then rose significantly to 5.4 in 2006 (APC: 41.27; 95 % CI: 24.49 to 58.72), increased to 6.9 in 2015 (APC: 2.64; 95 % CI: 0.43 to 4.33), and sharply to 14.4 in 2020 (APC: 17.20; 95 % CI: 14.55 to 21.77). For women, the AAMR was 4.0 (95 % CI: 3.9–4.1) in 1999, dropping to 2.5 (95 % CI: 2.4–2.6) in 2003 (APC: 16.90; 95 % CI: 42.69 to −4.40). It then rose to 6.3 in 2006 (APC: 47.66; 95 % CI: 24.87 to 70.74), slightly increased to 6.7 in 2015 (APC: 0.95; 95 % CI: 9.94 to 3.51), and sharply to 12.6 in 2020 (APC: 14.68; 95 % CI: 8.76 to 32.16) (Fig. 1, Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

3.3. Stratification by age groups

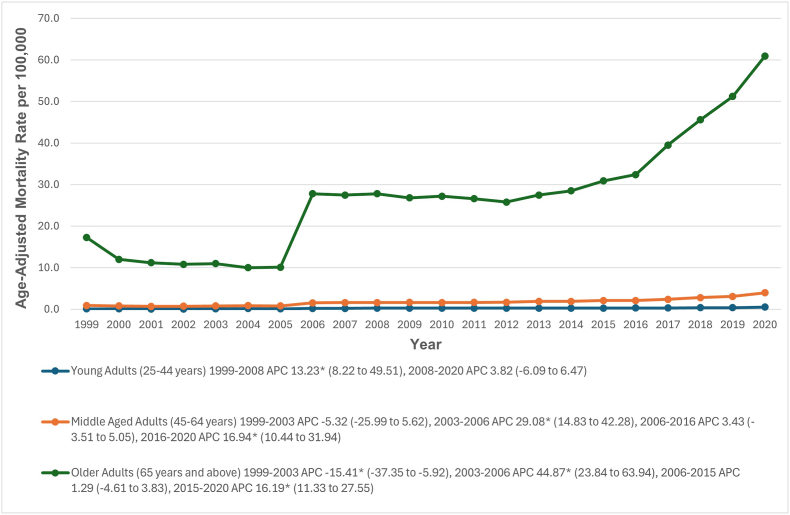

When stratified by age groups, older adults had the highest AAMRs (28.5; 95 % CI: 28.3–28.6), followed by middle-aged adults (1.8; 95 % CI: 1.8–1.8) and young adults (0.3; 95 % CI: 0.3–0.3). Among young adults, AAMRs significantly increased from 1999 to 2008 (APC: 13.23; 95 % CI: 8.22–49.51) and slightly increased from 2008 to 2020 (APC: 3.82; 95 % CI: 6.09 to 6.47). Middle-aged and older adults saw a decrease from 1999 to 2003 (APC: 5.32; 95 % CI: 25.99 to 5.62 and APC: 15.41; 95 % CI: 37.35 to −5.92) respectively, followed by significant increases (APC: 29.08; 95 % CI: 14.83 to 42.28 and APC: 44.87; 95 % CI: 23.84 to 63.94) respectively. From 2006 to 2016, middle-aged adults showed a slight increase (APC: 3.43; 95 % CI: 3.51 to 5.05), and older adults had a similar trend from 2006 to 2015 (APC: 1.29; 95 % CI: 4.61 to 3.83). A steep upward trend was observed from 2016 to 2020 in middle-aged adults (APC: 16.94; 95 % CI: 10.44 to 31.94) and from 2015 to 2020 in older adults (APC: 16.19; 95 % CI: 11.33 to 27.55) (Fig. 2, Supplemental Tables 3 and 5).

Fig. 2.

Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000, stratified by age groups in adults in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

∗ Indicates that the annual percentage change (APC) is significantly different from zero at α = 0.05. AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate.

3.4. Racial stratification

When stratified by race or ethnicity, AAMRs were highest among NH Black (10.9; 95 % CI: 10.8–11.1), followed by NH American Indian or Alaska Native (6.6; 95 % CI: 6.3–7.0), NH white (5.8; 95 % CI: 5.8–5.9), Hispanic (5.4; 95 % CI: 5.3–5.4), and NH Asian or Pacific Islander populations (3.9; 95 % CI: 3.8–4.0). From 1999 to 2006, AAMRs for American Indians or Alaska Natives were unreliable, but they increased slightly from 2006 to 2014, followed by a steep rise from 2014 to 2020 (APC: 20.58; 95 % CI: 15.86–30.29). AAMRs significantly decreased from 1999 to 2004 for Asian or Pacific Islander (APC: 10.43; 95 % CI: 29.15 to −0.98) and Black individuals (APC: 8.82; 95 % CI: 22.32 to −3.11) and from 1999 to 2003 for White (APC: 13.74; 95 % CI: 37.19 to −2.49) and Hispanic individuals (APC: 19.17; 95 % CI: 44.16 to −3.38). A significant upward trend occurred from 2004 to 2007 for Asian (APC: 53.32; 95 % CI: 25.74 to 74.42) and Black individuals (APC: 36.46; 95 % CI: 17.24 to 49.05), and from 2003 to 2006 for White (APC: 45.36; 95 % CI: 24.62 to 64.76) and Hispanic individuals (APC: 55.99; 95 % CI: 29.57 to 80.45). From 2007 to 2012, AAMRs significantly decreased for Asian (APC: 7.89; 95 % CI: 17.94 to −2.04) and slightly decreased for Black individuals (APC: 2.01; 95 % CI: 8.96 to 0.53) from 2007 to 2015. White individuals had a slight increase from 2006 to 2014 (APC: 0.93; 95 % CI: 8.23 to 3.94) and Hispanic individuals from 2006 to 2015 (APC: 0.95; 95 % CI: 11.46 to 3.84). Lastly, a significant upward trend was observed from 2012 to 2020 for Asian (APC: 7.55; 95 % CI: 5.44 to 11.65), from 2014 to 2020 for White (APC: 15.35; 95 % CI: 11.38 to 25.60), and from 2015 to 2020 for Black (APC: 10.65; 95 % CI: 6.13 to 20.14) and Hispanic individuals (APC: 15.31; 95 % CI: 9.65 to 31.79). (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Tables 3 and 6).

Fig. 3.

Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000, stratified by race in adults in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

∗ Indicates that the annual percentage change (APC) is significantly different from zero at α = 0.05. AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate.

3.5. State-wise distribution

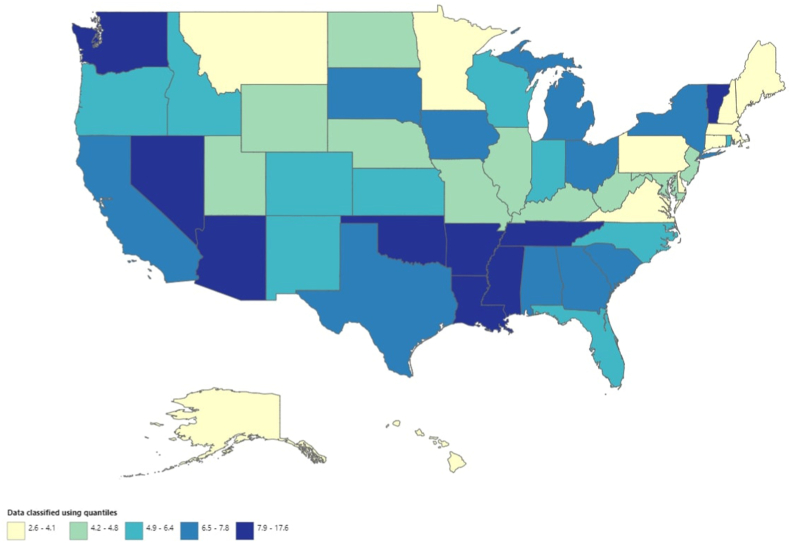

AAMR values varied significantly by state, ranging from 2.6 (95 % CI: 2.5–2.7) in Connecticut to 17.6 (95 % CI: 17.2–18.0) in Mississippi. States in the top 90th percentile (Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, District of Columbia, Oklahoma, Mississippi) had AAMRs about eight times as high as those in the bottom 10th percentile (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Alaska, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Hawaii) (Fig. 4, Supplemental Table 7)

Fig. 4.

Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000, stratified by state in adults in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

3.6. Census region

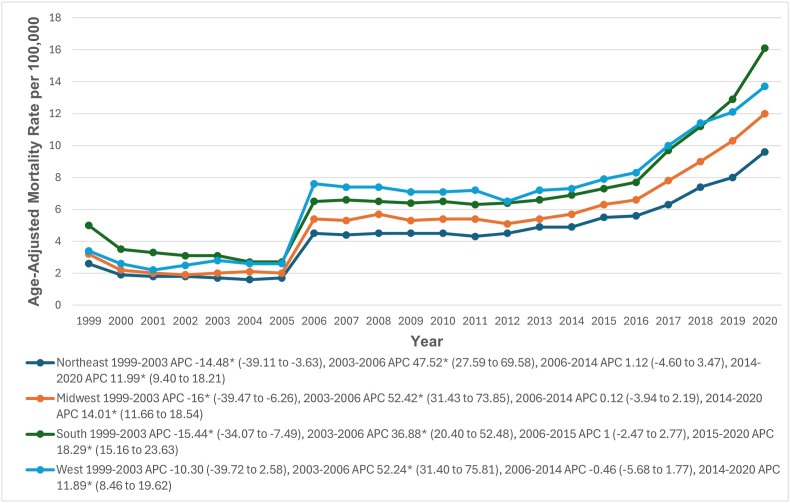

During the study period, the highest AAMR was in the Western region (7.2; 95 % CI: 7.2–7.3), followed by the southern (7.1; 95 % CI: 7.1–7.2), midwestern (5.5; 95 % CI: 5.5–5.6), and northeastern (4.6; 95 % CI: 4.5–4.6) regions. From 1999 to 2003, AAMRs decreased in the western region (APC: 10.30; 95 % CI: 39.72 to 2.58), and significantly in the northeastern (APC: 14.48; 95 % CI: 39.11 to −3.63), midwestern (APC: 16.0; 95 % CI: 39.47 to −6.26), and southern (APC: 15.44; 95 % CI: 34.07 to −7.49) regions. From 2003 to 2006, AAMRs increased significantly in all regions: Northeastern (APC: 47.52; 95 % CI: 27.59 to 69.58), Midwestern (APC: 52.42; 95 % CI: 31.43 to 73.85), Southern (APC: 36.88; 95 % CI: 20.40 to 52.48), and Western (APC: 52.24; 95 % CI: 31.40 to 75.81). There was a slight increase in AAMRs from 2006 to 2014 in the Northeastern and Midwestern regions, and from 2006 to 2015 in the Southern region (Northeastern APC: 1.12; 95 % CI: 4.60 to 3.47; Midwestern APC: 0.12; 95 % CI: 3.94 to 2.19; Southern APC: 1.00; 95 % CI: 2.47 to 2.77). From 2014 to 2020, AAMRs significantly increased in the Northeastern (APC: 11.99; 95 % CI: 9.40 to 18.21), Midwestern (APC: 14.01; 95 % CI: 11.66 to 18.54), and Western (APC: 11.89; 95 % CI: 8.46 to 19.62) regions, and from 2015 to 2020 in the Southern region (APC: 18.29; 95 % CI: 15.16 to 23.63) (Fig. 5, Supplemental Tables 3 and 8).

Fig. 5.

Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000, stratified by census regions in adults in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

∗ Indicates that the annual percentage change (APC) is significantly different from zero at α = 0.05. AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate.

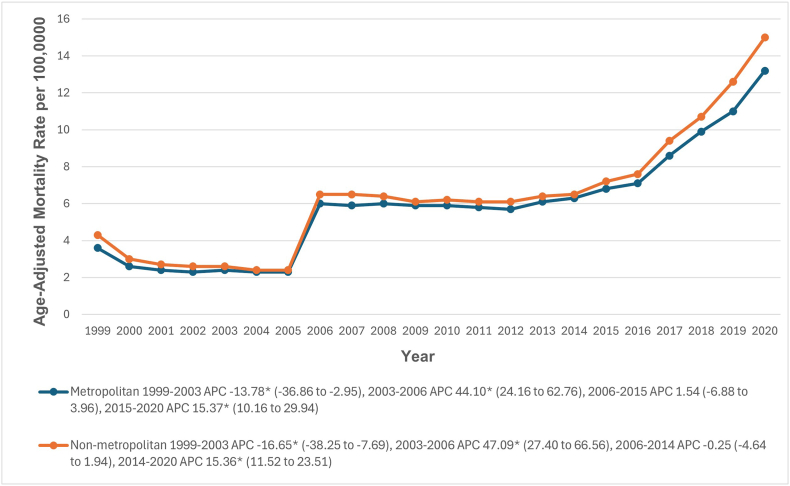

3.7. Urbanization

Throughout the study period, non-metropolitan areas had slightly higher AAMRs for HHD with HF than metropolitan areas, with overall AAMRs of 6.6 (95 % CI: 6.5–6.6) and 6.2 (95 % CI: 6.2–6.3), respectively. From 1999 to 2003, AAMRs decreased significantly in both non-metropolitan (APC: 16.65; 95 % CI: 38.25 to −7.69) and metropolitan areas (APC: 13.78; 95 % CI: 36.86 to −2.95). From 2003 to 2006, AAMRs significantly increased in non-metropolitan (APC: 47.09; 95 % CI: 27.40 to 66.56) and metropolitan areas (APC: 44.10; 95 % CI: 24.16 to 62.76). Between 2006 and 2015, AAMRs slightly increased in metropolitan areas (APC: 1.54; 95 % CI: 6.88 to 3.96) and decreased somewhat in non-metropolitan areas between 2006 and 2014 (APC: 0.25; 95 % CI: 4.64 to 1.94). Finally, there was a significant upward trend in AAMRs from 2014 to 2020 in non-metropolitan areas (APC: 15.36; 95 % CI: 11.52 to 23.51) and from 2015 to 2020 in metropolitan areas (APC: 15.37; 95 % CI: 10.16 to 29.94) (Fig. 6, Supplemental Tables 3 and 9).

Fig. 6.

Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000 in adults in the metropolitan and Non-metropolitan areas in the United States, 1999 to 2020.

∗ Indicates that the APC is significantly different from zero at α = 0.05. AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate.

3.8. Comparison of mortality rates pre-COVID-19 pandemic (1999–2019) versus during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022)

During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), the AAMR increased from 13.5 to 14.8, with an APC of 4.40 (95 % CI: 1.90 to 11.44). The average AAMR during the pandemic (14.5 per 100,000) was nearly three times as high as the pre-pandemic average from 1999 to 2019 (5.8 per 100,000) (Fig. 7, Supplemental Tables 1,3 and 10)

Fig. 7.

(A) Trend in hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000 in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2022) (B) Comparison of hypertensive heart disease with heart failure-related Average age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) per 100,000 during the COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2022) with the pre-pandemic period (1999–2019).

4. Discussion

Our analysis indicated a significant increase in mortality across various demographic groups, including age, race/ethnicity, geographical region, and urbanization status. Older adults consistently had higher AAMRs than younger adults, and NH Black individuals experienced the highest AAMRs, followed by NH American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Significant differences were also observed in the geographical analysis of states in the top 90th AAMR percentile, with rates up to eight times higher than those in the bottom 10th percentile and higher AAMRs in those residing in non-metropolitan areas. However, only slight differences were observed in the comparison of sex.

HHD arises from chronic hypertension-induced myocardial remodeling and ultimately leads to HF [16]. HHD encompasses a range of abnormalities that reflect lifelong structural and functional adaptations to sustained high blood pressure. Important intermediate characteristics of this condition include left ventricular hypertrophy, increased vascular and ventricular stiffness, and diastolic dysfunction, which progress concurrently with ischemic heart disease and, if untreated, result in HF [17,18]. The guidelines typically emphasize lifestyle changes, including dietary and exercise interventions and regular use of antihypertensive drugs [19]. In developed nations, high body mass index is a significant yet modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), potentially exacerbating HHD [20]. The precise mechanisms by which various risk factors affect HHD mortality remain unclear and warrant further investigation. The contribution of these risk factors to mortality may vary across different regions and is influenced by environmental, dietary, and behavioral variations. In some areas, high alcohol consumption is common and often linked to cultural practices. Alcohol intake can lead to myocardial fibroplasia and worsen myocardial hypertrophy [21], making targeted alcohol intervention a potential strategy to reduce the burden of HHD [22]. Consequently, it is crucial to encourage patients and at-risk populations to adopt healthier lifestyles and dietary patterns, such as reducing alcohol consumption and following plant-based low-fat diets.

The present analysis revealed a complex trajectory of AAMRs, with a pattern of initial decline followed by periods of increase. The AAMR was 3.7/100,000 in 1999, dropped until 2004, then increased significantly from 2004 to 2007, slightly decreased from 2007 to 2014, and sharply rose from 2014 to 2020, reaching 13.5 per 100,000. The initial trends align with previous studies indicating a decline in HF mortality from 2000 onwards [23]. This decrease is attributed to the lower overall CVD mortality rates in the late 20th century and early 2000s, driven by advancements in evidence-based medical and surgical treatments and global prevention strategies to reduce cardiovascular risk factors [24]. However, our analysis revealed a significant increase in HF mortality from 2014 to 2020. Several factors have contributed to this increase. First, the ongoing expansion of the elderly population aged ≥75 years in economically advanced countries has led to an increased burden of chronic illnesses, higher rates of hospitalization, and more documented deaths due to HF in this age group [25,26]. Second, the sharp rise coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, increased patient loads and limited emergency capacity led to reallocating medical resources and prioritizing COVID-19 patients. This has resulted in decreased hospital admissions for cardiovascular conditions and reduced access to acute cardiovascular care globally [27]. Consequently, many patients received inadequate treatment, lacked timely follow-up, and delayed seeking care, presenting later in a deteriorated state and contributing to increased mortality. Third, during the COVID-19 era, patients with comorbid conditions such as HF and HHD who developed severe COVID-19 were at a higher risk of complications, requiring intensive care and advanced medical services, which were overwhelmed during this period, leading to increased mortality. Lastly, HF patients, aware of their increased vulnerability, might have avoided hospitals because of fear of contracting COVID-19 [28,29].

The analysis revealed that older adults consistently had the highest AAMRs, which was expected given the higher prevalence of cardiovascular conditions in this age group. The higher prevalence of hypertension in older patients further contributes to the development of HHD. The significant increase in mortality rates among middle-aged and older adults, particularly from 2015 to 2020, underscores a critical area for intervention. This increase may be attributed to worsening cardiovascular health and potential healthcare access and management gaps for these populations. Notably, the global demographic landscape has experienced a significant increase in the aging population. In 1990, individuals over 60 years old accounted for 9.2 % of the global population, increasing to 11.7 % by 2013, with projections suggesting an increase to 21.1 % by 2050 [30]. This demographic shift is particularly relevant to HHD, which predominantly affects the elderly, thereby predicting a growing impact in this age group [31]. As HHD poses a substantial public health challenge worldwide, raising public awareness and enhancing the management strategies for HHD, especially among vulnerable populations, has become an urgent global priority.

Our study revealed significant racial disparities. Although NH Black individuals experienced the highest AAMRs, we noted a significant increase in AAMRs across all racial groups after 2014, suggesting the need for targeted public health strategies to address potential inequities in access to healthcare. It is essential to highlight that ethnic and racial disparities in CVD mortality remain significant across the United States [32]. Research has shown that adult Black men and women experience higher rates of CVD mortality, including HF, than other racial and ethnic groups. However, national-level data on sex-based disparities in cardiovascular conditions are currently lacking [33]. Black individuals face disproportionate economic, social, and environmental challenges along with structural racism, which contributes to their increased cardiovascular mortality and associated risk factors [34,35]. Black women, in particular, encounter additional challenges at the intersection of sexism and racism, negatively affecting their cardiovascular health and maternal outcomes [36]. However, no sex disparities were observed in our study.

As reported in previous studies, In 2012, the life expectancy of Black individuals was 3.4 years shorter than that of White individuals, with the most notable disparities observed when analyzed by race and sex: White women had the longest life expectancy at 81.4 years, followed by Black women at 78.4 years, White men at 76.7 years, and Black men at 72.3 years [37]. Hypertension accounts for 50 % of racial disparities in mortality between Black individuals and White individuals. Despite extensive genome-wide association studies, no specific genetic causes have been identified for the excessive burden among Black individuals. Pathophysiology likely involves a complex interplay of genetic, biological, and social factors that are prevalent in this population [38].

Furthermore, throughout the study period, non-metropolitan areas had slightly higher AAMRs for HHD with HF than did metropolitan areas. The geographic isolation of non-metropolitan areas makes it challenging for individuals in these regions to access medical care, which is further compounded by socioeconomic disparities. Residents of non-metropolitan areas must travel greater distances to reach healthcare facilities, and the number of healthcare practitioners is significantly lower than that in metropolitan regions. Cultural and behavioral factors, such as higher smoking rates, along with the shortage of healthcare professionals in these regions, exacerbate disparities in health outcomes and access to care. Although governmental and nonprofit organizations have implemented programs to address these disparities, the gaps continue to widen [39,40].

Previous studies have examined HF from all causes [41,42], but our analysis specifically targeted HHD with HF, which arises from structural and functional changes in the heart due to prolonged hypertension. Earlier HF studies showed that AAMRs for HF in young adults increased by 5 % annually from 2011 to 2019 [41], and by 1.7 % annually in older adults from 2012 to 2019 [42]. In contrast, our analysis revealed that AAMRs for HHD with HF increased by 14 % annually from 2014 to 2020. Furthermore, our findings highlight slight differences in AAMRs between men and women (6.3 vs. 6.1), with annual increases of 17 % and 14 % from 2015 to 2020, respectively. This differs from previous HF studies, which consistently reported higher AAMRs for men (3.04 in young and 141.1 in older) than for women (1.87 in young and 107.8 in older), with much smaller annual increases of 1 %–5 % in both young and older adults [41,42].

In terms of racial disparities, our analysis aligns with previous HF studies on young adults, showing that NH Black individuals had the highest AAMRs (6.77) throughout the study period [41]. However, earlier studies on older adults with HF found that NH white individuals had the highest AAMRs (127.2) [42]. Finally, our urbanization-based analysis aligns with previous studies, indicating higher AAMRs in non-metropolitan areas than in metropolitan areas (6.6 vs. 6.2, respectively) [41,42]. Thus, these findings highlight that HHD with HF is a separate entity that deserves unique attention with prominent disparities.

Given the substantial mortality burden of HHD-associated HF, urgent population-wide policy measures are needed to eliminate the disparities above and target individuals for HF prevention earlier in life. The rising trend in HHD-related HF should not only prompt efforts to prevent, recognize, and treat the condition effectively but also serve as an opportunity to promote cardiovascular prevention across entire communities. This includes reducing the prevalence of contributors, such as obesity, smoking, poor diet, and physical inactivity. Additionally, active tracking and mitigation of modifiable and non-genetic risk factors contributing to HHD and HF can potentially improve population-wide health with a focus on achieving equity across diverse communities.

4.1. Limitations

First, as with any study that relies on a large nationwide administrative database, potential miscoding cannot be excluded, which may have affected the accuracy of our results. It is unclear to what extent changes in the quality of information on death certificates over time might account for the rising number of deaths attributed to HHD associated with HF. Additionally, the data did not distinguish whether changes in AAMRs were due to variations in disease incidence or case-fatality rates. Second, the ICD-10 codes used in the CDC WONDER datasets primarily capture diagnostic information rather than detailed clinical data or patient characteristics. Although these codes provide an overview of the patient's condition, they may omit crucial factors influencing mortality, such as comorbidities, disease severity, treatment protocols, or other relevant clinical variables. This limitation may have restricted the depth of our analysis when assessing the relationship between HHD-related HF and AAMRs. Third, the CDC WONDER dataset focuses on mortality and lacks data on previous cardiovascular history, heart function status, and potential competing causes of death, further constraining our analysis. Death certificates can also underestimate cardiovascular mortality in younger subjects, adding another layer of complexity. Despite these limitations, death certificates remain a primary source for examining the trends and epidemiology of HHD-related HF because of their value as population-based data sources. Lastly, the absence of clinical and laboratory characteristic data in the CDC WONDER database prevented us from conducting detailed subgroup analyses, propensity score matched analysis, or pairwise comparison analysis based on factors such as socioeconomic status, comorbid conditions, medication adherence, and management, particularly adherence to hypertension and HF medications and advanced therapies. This lack of information leaves a knowledge gap, making it challenging to identify the underlying causes of rising death rates.

5. Conclusions

The mortality rate due to HHD with HF has risen in the past two decades, with higher mortality observed among older adults, NH Black individuals, and those residing in non-metropolitan areas. However, no significant sex disparities were noted. Despite substantial treatment and secondary prevention advances, this study emphasizes demographic differences. These findings necessitate immediate public health actions to reduce these potential disparities.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aman Goyal: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Humza Saeed: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ajeet Singh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Abdullah: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation. Wania Sultan: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zubair Amin: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. Hritvik Jain: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Zainali Chunawala: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision. Mohamed Daoud: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision. Sourbha S. Dani: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Ethical considerations

No ethical approval was required for this study design, as all data were obtained from publicly available sources.

Funding

N/A.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Handling editor: D Levy

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcrp.2025.200378.

Contributor Information

Aman Goyal, Email: amanmgy@gmail.com.

Humza Saeed, Email: hamzasaeed309@gmail.com.

Ajeet Singh, Email: ajeetsinghsodho95@gmail.com.

Abdullah, Email: abdulahabid6@gmail.com.

Wania Sultan, Email: waniabintsultan@gmail.com.

Zubair Amin, Email: zubair.amin1997@gmail.com.

Hritvik Jain, Email: hritvikjain2001@gmail.com.

Mohamed Daoud, Email: drmohameddaoudmd@gmail.com.

Sourbha S. Dani, Email: Sourbha.S.Dani@lahey.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Blood pressure/hypertension [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/3155.

- 2.Díez J., Butler J. Growing heart failure burden of hypertensive heart disease: a call to action. Hypertension. 2023 Jan 1;80(1):13–21. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19373. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D., Larson M.G., Vasan R.S., Kannel W.B., Ho K.K.L. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA. 1996 May 22;275(20):1557. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/402794 62. [Internet] [cited 2024 Jun 9] Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad F.S., Ning H., Rich J.D., Yancy C.W., Lloyd-Jones D.M., Wilkins J.T. Hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and heart failure–free survival: the cardiovascular disease lifetime risk pooling Project. JACC Hear Fail. 2016 Dec 1;4(12):911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno M.U., González A., López B., Ravassa S., Beaumont J., San José G., et al. Hypertensive heart disease. Encycl Cardiovasc Res Med. 2023 Jun 26;1–4:517–526. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539800/ [Internet].[cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Palo K.E., Barone N.J. Hypertension and heart failure: prevention, targets, and treatment. Heart Fail. Clin. 2020 Jan 1;16(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.09.001. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31735319/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W.L., Yuan J.H., Liu Z.Y., Su Z.H., Shen Y.C., Li S.J., et al. Worldwide trends in mortality for hypertensive heart disease from 1990 to 2019 with projection to 2034: data from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024 Jan 5;31(1):23–37. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwad262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saliba L.J., Maffett S. Hypertensive heart disease and obesity: a review. Heart Fail Clin [Internet] 2019 Oct 1;15(4):509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.06.003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31472886/ [cited 2024 Jun 10] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díez J., Butler J. Growing heart failure burden of hypertensive heart disease: a call to action. Hypertension. 2023 Jan 1;80(1):13–21. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19373. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ESH hypertension guideline update: bringing us closer together across the pond - American college of cardiology. 2023. https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2024/02/05/11/43/2023-ESH-Hypertension-Guideline-Update [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 10]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code I11.0: hypertensive heart disease with heart failure. 2025. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/I00-I99/I10-I1A/I11-/I11.0 [Internet]. Icd10data.com. 2016. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth [Internet] 2019 Apr 1;13(Suppl 1):S31. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18. [cited 2024 Mar 18] Available from:/pmc/articles/PMC6398292/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ICD-10 Version:2019 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 20]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/N08.3.

- 14.NCHS urban-rural classification Scheme for counties - PubMed. 2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24776070/ [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joinpoint Regression Program [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Available from: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/.

- 16.Di Palo K.E., Barone N.J. Hypertension and heart failure: prevention, targets, and treatment, Heart Fail. Clin. 2020;16(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izzo JL Jr, Gradman A.H. Mechanisms and management of hypertensive heart disease: from left ventricular hypertrophy to heart failure. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88(5):1257–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman E., Messerli F.H. Diabetic and hypertensive heart disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125(4):304–310. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whelton P.K., Carey R.M., Aronow W.S., Casey D.J., Collins K.J., Dennison H.C., DePalma S.M., Gidding S., Jamerson K.A., Jones D.W., et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;71(19):2199–2269. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J.G., Zhang W., Li Y., Liu L. Hypertension in China: epidemiology and treatment initiatives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023;20(8):531–545. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00829-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohlrogge A.H., Frost L., Schnabel R.B. Harmful impact of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption on the atrial myocardium. CELLS-BASEL. 2022;11(16) doi: 10.3390/cells11162576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roerecke M., Kaczorowski J., Tobe S.W., Gmel G., Hasan O., Rehm J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2):e108–e120. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Win T.T., Davis H.T., Laskey W.K. Mortality among patients hospitalized with heart failure and diabetes mellitus. Circulation: Heart Fail. 2016;9(5) doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mensah G.A., Wei G.S., Sorlie P.D., et al. Decline in cardiovascular mortality. Circ. Res. 2017;120(2):366–380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldacre M.J. Mortality from heart failure in an English population, 1979-2003: study of death certification. J. Epidemiol. Community. 2005;59(9):782–784. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw C. Interim 2001-based national population projections for the United Kingdom and constituent countries. Popul Trends. Spring. 2003;111:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morishita T., Takada D., Shin J., et al. Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on heart failure hospitalizations in Japan: interrupted time series analysis. Esc Heart Failure. 2021;9(1):31–38. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt A.S., Moscone A., McElrath E.E., et al. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76(3):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonarow G.C., Ziaeian B. Hospital readmission reduction program for heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73(9):1013–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritchey M.D., Wall H.K., George M.G., Wright J.S. US trends in premature heart disease mortality over the past 50 years: where do we go from here? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020;30(6):364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou B., Perel P., Mensah G.A., Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021;18(11):785–802. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00559-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kung HC, Xu J. 2015. Hypertension-related mortality in the United States, 2000-2013; pp. 1–8.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25932893/nchsdatabrief [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidney S., Quesenberry C.P., Jr, Jaffe M.G., et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:594–599. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rethy L., Shah N.S., Paparello J.J., Lloyd-Jones D.M., Khan S.S. Trends in hypertension-related cardiovascular mortality in the United States, 2000 to 2018. Hypertension. 2020 doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.15153. 76:0–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah N.S., Lloyd-Jones D.M., O'Flaherty M., Capewell S., Kershaw K.N., Carnethon M., Khan S.S. Trends in cardiometabolic mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:780–782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ouyang F., Cheng X., Zhou W., He J., Xiao S. Increased mortality trends in patients with chronic noncommunicable diseases and comorbid hypertension in the United States, 2000-2019. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.753861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carnethon M.R., Pu J., Howard G., et al. Cardiovascular health in african Americans: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2017;136 doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000534. 0–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musemwa N., Gadegbeku C.A. Hypertension in african Americans. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2017;19:129. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zahnd W.E., Hung P., Crouch E.L., Ranganathan R., Eberth J.M. Health care access barriers among metropolitan and nonmetropolitan populations of eight geographically diverse states. J. Rural Health. 2018 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12855. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clove David. “Healthcare access disparities among rural populations in the United States” ballard brief. February 2023. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu

- 41.Jain V., Minhas A.M.K., Morris A.A., et al. Demographic and regional trends of heart failure–related mortality in young adults in the US, 1999-2019. JAMA Cardiology. 2022;7:900. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siddiqi TJ, Khan Minhas AM, Greene SJ, et al. Trends in Heart Failure Related Mortality Among Older Adults in the US From 1999-2019. JACC (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.): Heart Fail.; 10. Epub ahead of print September 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.