This prespecified analysis of the Aspirin and Hemocompatibility Events With a Left Ventricular Assist Device in Advanced Heart Failure (ARIES-HM3) randomized clinical trial investigates if common conditions for which aspirin is indicated influence outcomes differentially when aspirin is removed from the antithrombotic regimen in patients who receive the HeartMate 3 (HM3 [Abbott Cardiovascular]) left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Key Points

Question

Do common conditions (prior percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG], stroke, or peripheral vascular disease [PVD]) for which aspirin is indicated influence outcomes differentially when aspirin is eliminated from the antithrombotic regimen in recipients of the Heartmate 3 (HM3 [Abbott Cardiovascular]) left ventricular assist device (LVAD)?

Findings

In this prespecified analysis of the Aspirin and Hemocompatibility Events With a Left Ventricular Assist Device in Advanced Heart Failure (ARIES-HM3) randomized clinical trial, the presence of an atherosclerotic vascular condition did not modify the observed benefit of aspirin avoidance on the primary outcome (survival free of any nonsurgical hemocompatibility-related adverse events, including stroke, pump thrombosis, bleeding, and arterial peripheral thromboembolism at 12 months) or secondary outcome of reduction in nonsurgical bleeding.

Meaning

Prior PCI, stroke, PVD, or CABG should not compel physicians to use aspirin as part of the antithrombotic regimen with the HM3 LVAD.

Abstract

Importance

The Aspirin and Hemocompatibility Events With a Left Ventricular Assist Device in Advanced Heart Failure (ARIES-HM3) study demonstrated that aspirin may be safely eliminated from the antithrombotic regimen after HeartMate 3 (HM3 [Abbott Cardiovascular]) left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation. This prespecified analysis explored whether conditions requiring aspirin (prior percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG], stroke, or peripheral vascular disease [PVD]) would influence outcomes differentially with aspirin avoidance.

Objective

To analyze aspirin avoidance on hemocompatibility-related adverse events (HRAEs) at 1 year after implant in patients with a history of CABG, PCI, stroke, or PVD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was an international, multicenter, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial including patients implanted with a de novo HM3 LVAD across 51 centers. Data analysis was conducted from April to July 2024.

Interventions

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive aspirin (100 mg per day) or placebo, in addition to a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) targeted to an international normalized ratio of 2 to 3 in both groups.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary end point (assessed for noninferiority) was a composite of survival free of any nonsurgical (>14 days after implant) HRAEs including stroke, pump thrombosis, bleeding, and arterial peripheral thromboembolism at 12 months. Secondary end points included nonsurgical bleeding, stroke, and pump thrombosis events.

Results

Among 589 of 628 patients (mean [SD] age, 57.1 [13.7] years; 456 male [77.4%]) who contributed to the primary end point analysis, a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD was present in 41% (240 of 589 patients). There was no interaction between the presence of an atherosclerotic vascular condition and effect of aspirin compared with placebo (P for interaction= .23). The preset 10% noninferiority margin was not crossed for the studied subgroup of patients. Thrombotic events were rare, with no differences between aspirin and placebo in patients with and without vascular disease (P for interaction = .77). Aspirin treatment was associated with a higher rate of nonsurgical major bleeding events in the group with prior vascular condition history compared with those without aspirin (rate ratio for placebo compared with aspirin, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35-0.79).

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this prespecified analysis of the ARIES-HM3 randomized clinical trial demonstrate that in patients with advanced heart failure who have classical indications for antiplatelet therapy use at the time of LVAD implantation, aspirin avoidance was safe and not associated with increased thrombosis risk. Importantly, elimination of aspirin was associated with no increased thrombosis but a reduction in nonsurgical bleeding events in patients with a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04069156

Introduction

For decades, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) has been recommended for secondary prevention in various acute and chronic cardiovascular conditions, such as acute and chronic coronary syndromes, cerebral vascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD).1,2,3,4,5,6 In patients with heart failure (HF), these atherosclerotic comorbidities are common, with approximately 50% receiving aspirin according to recent registries.7,8,9

In advanced HF, durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are indicated to enhance survival, physical capacity, and quality of life, serving as a bridge to transplant or as life-long therapy.10,11 The Heartmate 3 (HM3 [Abbott Cardiovascular]) LVAD, a durable fully magnetically levitated pump, has shown superior outcomes compared with legacy devices, with a median survival exceeding 5 years after implantation.12,13,14,15 To prevent thrombotic complications related to the pump and outflow graft, antithrombotic prophylaxis is mandatory. Currently, the recommended regimen for the HM3 LVAD includes a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 2 to 3 combined with low-dose aspirin (75-325 mg daily). Despite reducing the risk of pump thrombosis to less than 1%, along with a marked reduction in stroke rates, this regimen is associated with a high incidence of bleeding complications, partly due to the pump’s impact on blood components, such as acquired von Willebrand syndrome.16,17 Therefore, identifying the optimal antithrombotic regimen to minimize hemocompatibility-related adverse events (HRAEs) remains uncertain, particularly in those patients with preexisting arterial vascular disease.

The recent Aspirin and Hemocompatibility Events With a Left Ventricular Assist Device in Advanced Heart Failure (ARIES-HM3) randomized clinical trial suggested that aspirin can be safely omitted after HM3 LVAD implantation.18 It found that eliminating aspirin and using VKA alone was safe and resulted in fewer nonsurgical bleeding events compared with the standard VKA plus aspirin regimen. In this prespecified secondary trial-level analysis, we explored whether common conditions requiring aspirin (ie, prior percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG], stroke, or PVD) in recipients of the HM3 LVAD would influence outcomes differentially when aspirin was eliminated.18

Methods

The ARIES study was a randomized clinical trial conducted in 51 countries in North America, Europe, Kazakhstan, and Australia comparing placebo or aspirin in addition to VKA therapy (target INR, 2.0-3.0) in patients with advanced HF undergoing implantation with the HM3 LVAD. Details of the trial rationale, design, and primary results have been previously published (Supplement 1).18,19 Patients not requiring mechanical circulatory support after implantation other than the HM3 LVAD and who were able to take oral aspirin (100 mg) or placebo 7 days after LVAD implantation were eligible for randomization. Patients self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, other (which included Hispanic/Latino, Levantine, or multiethnic), or refused to provide. Patients provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by national or regional ethics committees. Events were reviewed by a clinical events committee, which adjudicated all primary end points and adverse events related to the primary or secondary outcomes. In this comprehensive secondary outcome analysis, patients were grouped into those with and without a medical history of arterial vascular disease classically associated with a long-term indication for antiplatelet therapy with aspirin (prior PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Primary End Point

The primary end point consisted of a composite of survival free of nonsurgical major HRAEs (ie, stroke, pump thrombosis, major nonsurgical bleeding, and arterial peripheral thromboembolism) at 12 months. Patients with end points occurring within 14 days after LVAD implantation were excluded from the primary end point analysis (to avoid counting surgical complications not attributed to the treatment) (eAppendix in Supplement 2). Major nonsurgical bleeding included both moderate and severe bleeding events if occurring more than 14 days after LVAD implantation.20

Main Secondary and Safety End Points

The principal secondary end point was moderate and severe nonsurgical bleeding assessed as first and recurrent events. This end point was described in events per 100 patient-years. Survival, stroke, and pump thrombosis rates were compared between the 2 study groups among those with and without aspirin (placebo) to assess the safety of omitting aspirin in the distinct subgroups of interest.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and proportions. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate. Between-group comparisons were evaluated using Fisher exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. Patients who withdrew from the study without experiencing a prior primary end point event were not included in the primary end point set. Transplant, explant of the LVAD due to recovery, or transition to open-label aspirin use (based on investigator preference) without nonsurgical major HRAEs was considered treatment success. Interaction testing of the primary end point subgroups was performed by generalized linear modeling with terms for treatment group, subgroup, and their interaction evaluated at an interaction significance level of .15. Time to first event comparing treatment groups at 24 months by the Kaplan-Meier method was done to evaluate events over longer follow-up duration. Events in the aspirin and placebo groups, and the groups with and without prior indication for aspirin, were compared as rate of events per 100 patient-years and tested using Poisson regression. Plots of mean cumulative hazard rates were constructed using Nelson-Aalen estimator over 24 months for secondary end points. P values were 2-tailed, and P values <.05 were considered significant unless otherwise noted. Data analysis was conducted from April to July 2024 and performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

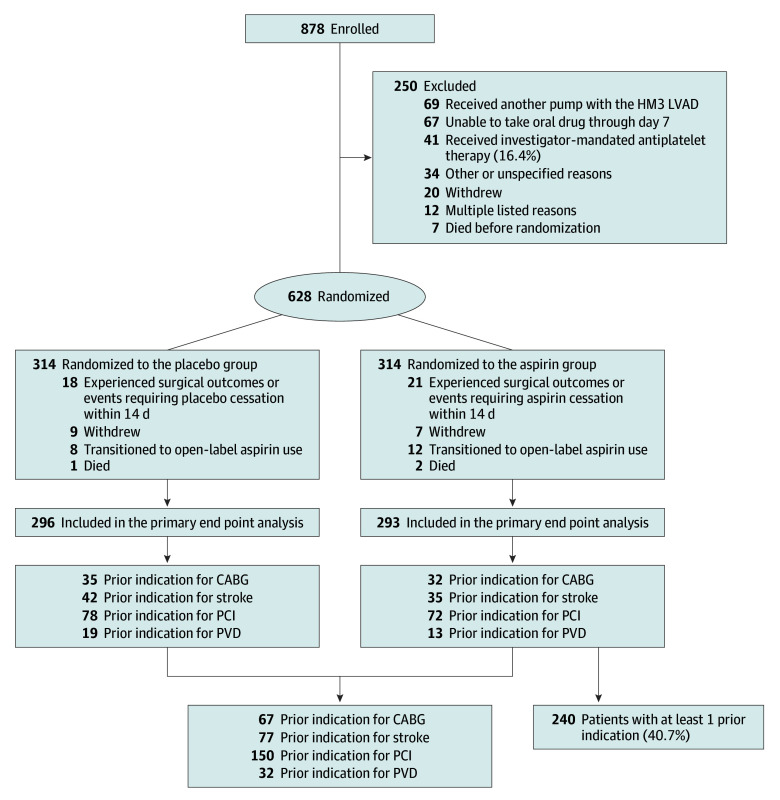

The ARIES HM3 trial enrolled 878 patients of whom 628 underwent randomization in the study. A minority of exclusions were explained by the investigators’ perception of requirement for open-label aspirin (41 patients [16%] of all excluded patients) (Figure 1). Of the 628 randomized patients, 39 were not included in the primary end point analysis mainly because of surgical events within 14 days after implantation mandating cessation of study drug, leaving 589 patients (mean [SD] age, 57.1 [13.7] years; 133 female [22.6%]; 456 male [77.4%]) in the primary end point population. Patients self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: 22 Asian (3.7%), 177 Black or African American (30.1%), 5 Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (0.8%), 360 White (61.1%), 6 other (1.0%), and 19 refused to provide (3.2%). A history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD was noted in 240 individuals (41% of the primary end point population), with prior PCI being the most common condition (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics and medical history of patients in the individual components of the subgroups are shown in eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2, with a further breakdown depending on randomization results in eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 2. Prior events were mostly distant to the LVAD implantation procedure. For instance, 32 patients had undergone PCI within the last year before LVAD implantation (21% of 150 patients in total with prior PCI) and only 19 within 6 months of the LVAD procedure.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Study Detailing Patients With and Without a History of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Stroke, or Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD).

Patients who were enrolled and randomized in the Aspirin and Hemocompatibility Events With a Left Ventricular Assist Device in Advanced Heart Failure (ARIES-HM3) study were identified by the presence of at least one of the following prior conditions: PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD. HM3 indicates HeartMate 3 (Abbott Cardiovascular); LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD are presented in the Table, and baseline laboratory tests and hemodynamic parameters are reported in eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2, respectively. Cases of multiple aspirin indications are reported in eTable 7 in Supplement 2, and eTable 8 in Supplement 2 reports the use of P2Y12 agents before the LVAD implant and discontinued at the time of inclusion into the trial. Patients with a history of any of the vascular comorbidities were older, more commonly White race, more often had diabetes and had undergone sternotomy, and less often had an Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support, or INTERMACS, grade of 1 to 3 (ie, more severely advanced HF being at least inotrope dependent) compared with patients without such a history. Moreover, patients with a history of systemic vascular disease (as defined by the four groups) more often had atrial fibrillation and a history of bleeding. Importantly, time in therapeutic range (TTR) for the VKA treatment (INR, 2-3) throughout the study was similar in the 2 groups at a mean (SD) of 54.2% (23.4%) and 54.9% (21.6%; P = .86) (Table). The allocation to aspirin and placebo was well balanced in both subgroups.

Table. Baseline Characteristics Stratified by a History of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Stroke, or Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD).

| Characteristics | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| History of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD (n = 240) | No history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD (n = 349) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.7 (10.8) | 53.9 (14.5) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 50 (20.8) | 83 (23.8) | .42 |

| Male | 190 (79.2) | 266 (76.2) | .42 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 2 (0.8) | 20 (5.7) | .001 |

| Black or African American | 63 (26.3) | 114 (32.7) | .10 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) | .40 |

| White | 163 (67.9) | 197 (56.4) | .006 |

| Othera | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.1) | >.99 |

| Refused to provide | 7 (2.9) | 12 (3.4) | .81 |

| Diabetes | 112 (46.7) | 128 (36.7) | .01 |

| Prior sternotomy | 69 (28.8) | 18 (5.2) | <.001 |

| INTERMACS 1-3 | 169 (70.4) | 278 (79.7) | .011 |

| History of bleeding | 18 (7.5) | 11 (3.2) | .02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 118 (49.2) | 141 (40.4) | .04 |

| TTR in study, mean (SD) [No.], % | 54.2 (23.4) [227]b | 54.9 (21.6) [327]b | .86 |

Abbreviations: INTERMACS, Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; TTR, time in therapeutic range.

Other race/ethnicity included Hispanic/Latino, Levantine, and multiethnic.

In instances where data may be missing for some subset of patients, total numbers are provided as [No.] to describe the population where the specific data point is available.

Effect of Aspirin on Primary and Secondary End Points

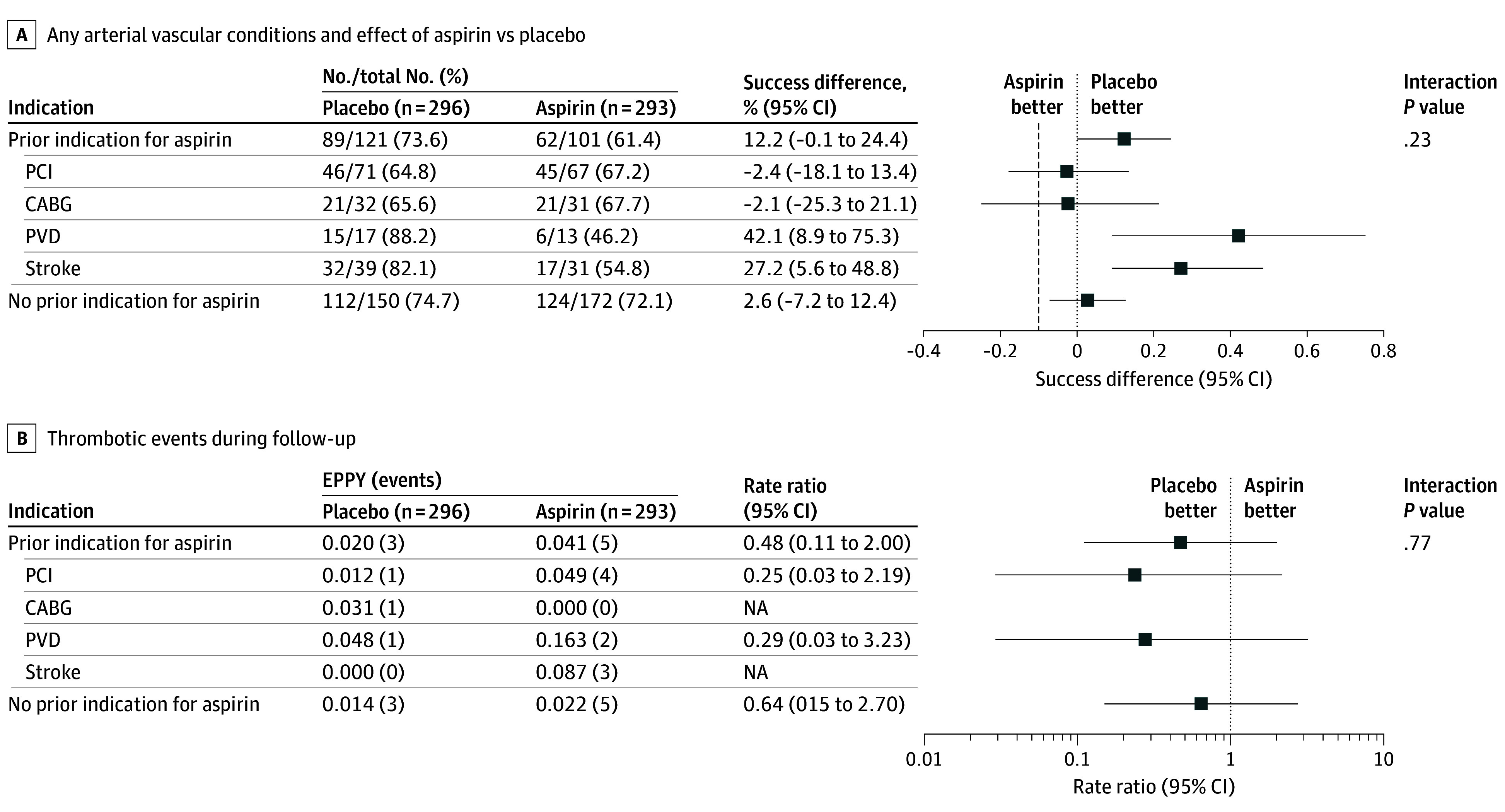

With respect to the primary end point, there was no interaction between presence of any of the arterial vascular conditions and effect of aspirin compared with placebo (P for interaction= .23) (Figure 2). The lower boundary of the 1-sided 97.5% confidence limit of the difference in the composite success rate between treatment groups (placebo − aspirin) was greater than the noninferiority margin (−10%) by the Farrington-Manning test at 12 months in the primary analysis population, and this, too, was not crossed for the subgroup of patients with a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD. None of the 4 components of the atherosclerotic vascular disease subgroup appear to deviate from the overall analysis with respect to the safety of aspirin avoidance, but power of the analysis in the individual subcategories is limited. Thrombotic events during follow-up were rare in both groups and there was no indication of a difference between aspirin and placebo in either (P interaction 0.77) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Incidence of the Primary End Point and Thrombotic Events in Patients With and Without a History of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Stroke, or Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD) Assigned to Aspirin or Placebo.

A, With respect to the primary end point, there was no interaction between presence of any of the arterial vascular conditions and effect of aspirin compared with placebo (P for interaction = .23). The vertical dashed line indicates the noninferiority margin. B, Thrombotic events during follow-up were rare in both groups, and there was no indication of a difference between aspirin and placebo (P for interaction = .77). The primary end point was the survival free of hemocompatibility-related adverse events: stroke, pump thrombosis, major nonsurgical bleeding, and arterial peripheral thromboembolism. This excluded patients who were withdrawn from study drug treatment before experiencing primary end point.

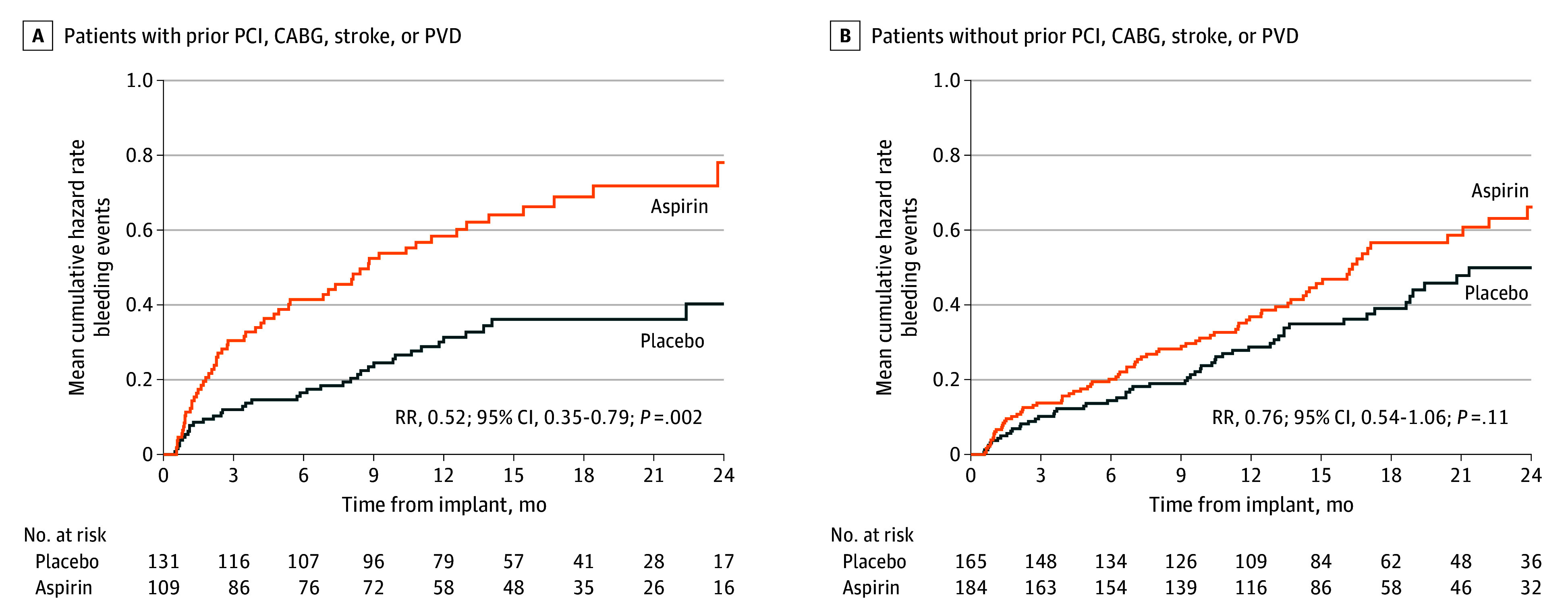

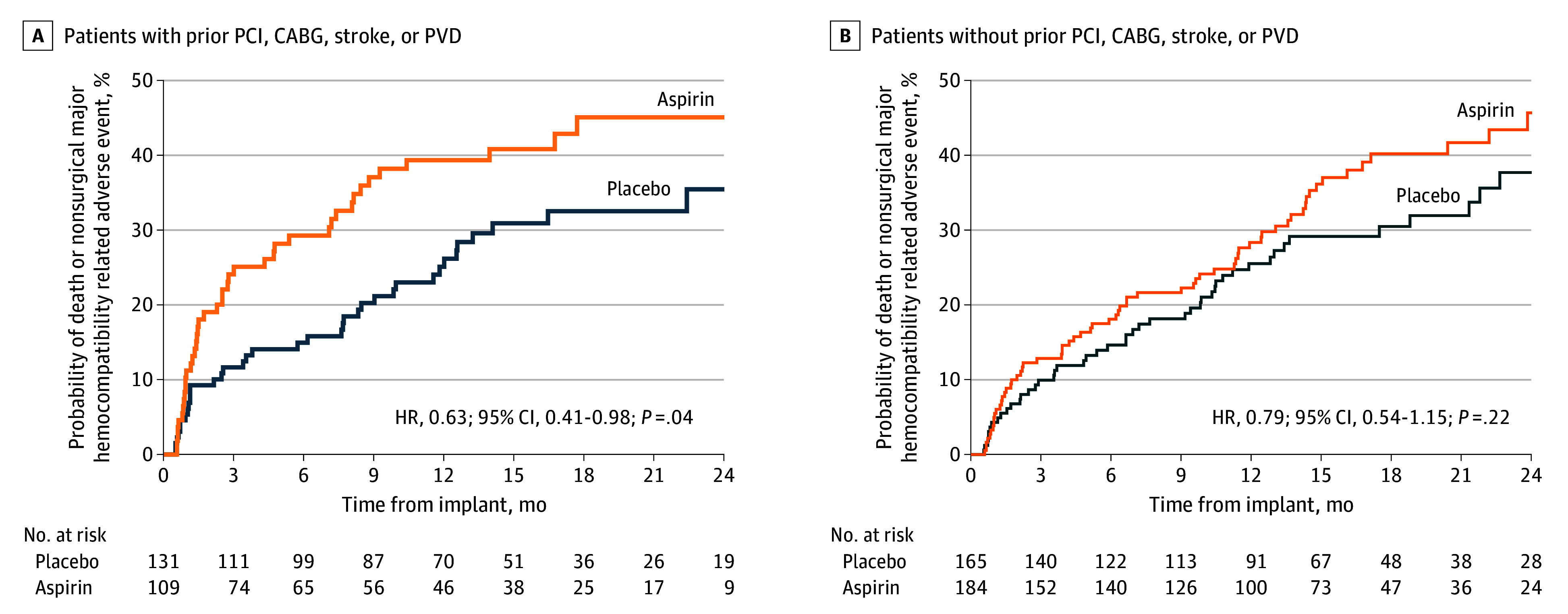

The overall cumulative incidence of nonsurgical major bleeding events was higher in the group with a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD compared with the subgroup without a history of arterial vascular disease (Figure 3). However, the increased rate of bleeding events in the group with a history of vascular disease was due to randomization to aspirin (rate ratio [RR] for placebo compared with aspirin, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35-0.79), whereas the difference in bleeding between aspirin and placebo was attenuated for patients without a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.54-1.06). The individual groups of patients with a recent PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD within 6 months were too small to allow for meaningful statistical analyses and therefore not analyzed. The proportion of patients reporting indication within 12 months from HM3 implant is reported in eTable 9 in Supplement 2. The survival free from death and nonsurgical HRAE analysis reported a significant reduction in hazard ratio (HR) at 24 months between aspirin and placebo for patients with prior indication for aspirin (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.98; P = .04) but not in patients without such indication (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.54-1.15; P = .22) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Cumulative Hazard Rates for Moderate or Severe Nonsurgical Bleeding Events Stratified by History of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Stroke, or Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD).

Although the cumulative incidence of nonsurgical major bleeding events was higher in the group with a prior history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD, the increased rate of bleeding events in the group with a history of vascular disease was due to randomization to aspirin: the rate ratio (RR) for placebo compared with aspirin was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.35-0.79), whereas the difference in bleeding between aspirin and placebo was attenuated for patients without a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD with an RR of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.54-1.06).

Figure 4. Time-to-Event Analysis of the Primary End Point Stratified by History of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), Stroke, or Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD).

The survival free from death and nonsurgical hemocompatibility-related adverse event analysis reported a significant reduction in hazard ratio (HR) between aspirin and placebo for patients with prior indication for aspirin (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.98; P = .04) but not in patients without such indication (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.54-1.15; P = .22).

Discussion

In this prespecified analysis of the ARIES trial, we tested the efficacy and safety of aspirin elimination among those with preexisting arterial vascular disease undergoing durable LVAD implantation. The study has important considerations and findings. First, we showed that a substantial proportion (41%) of patients undergoing LVAD implantation had a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD, conditions associated with a classical indication for aspirin use as secondary prophylaxis. Second, the trial excluded only few patients because of an investigator-perceived indication for open-label aspirin, an observation that points to generalizability of the ARIES-HM 3 trial. Third, avoidance of aspirin even in patients with a history of prior PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD did not lead to an increased incidence of thrombosis, and instead, we observed that elimination of aspirin led to a large and meaningful reduction in the risk for major, nonsurgical bleeding in this distinct subgroup with arterial vascular disease.

Aspirin has been a cornerstone in preventing thrombotic events for over a century and is still recommended for secondary prevention in patients with prior PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD according to guidelines.2,3,4,5,6 However, if patients are receiving VKA or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) due to conditions like atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves, the use of aspirin is typically limited to the acute phase after the events, due to concerns for an increased risk of bleeding.5 The ARIES-HM3 trial demonstrated that avoiding aspirin among patients receiving a durable LVAD can be safe and reduces bleeding risk, although concerns remain for high-risk subgroups prone to thrombotic events. Earlier experiences with lenient antithrombotic strategies in legacy devices have underscored the risk of pump thrombosis.21 As patients are now living longer with LVADs, exceeding 5 to 10 years in most cases, there is a cumulative risk of arterial vascular complications, especially in high-risk populations. This subanalysis from the ARIES-HM3 trial has provided reassurance that aspirin omission is safe even in patients with a history of remote PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD undergoing HM3 LVAD implantation. However, these findings may be specific to the HM3 LVAD and not generalizable to other durable LVAD technologies.

Nonsurgical bleeding risk was notably high among the ARIES-HM3 population, especially in those with a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD. This increased risk in this subgroup is likely attributed to underlying comorbidity in such populations characterized by common bleeding risk factors such as older age, diabetes, and prior sternotomy. Avoiding aspirin brought the bleeding risk in line with that seen in patients without these histories. These findings suggest that a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD does not necessitate aspirin use for thrombosis prevention after HM3 implantation but instead identifies patients who may have a greater risk of adverse effects with aspirin, leading to higher rates of bleeding, in the unique milieu provided by LVADs. Freedom from HRAEs in patients without a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD was numerically similar between those randomized to aspirin and placebo (Figure 2A). However, potential inferences about greater safety of aspirin in this group cannot be made based on this analysis further supported by the fact that P value for interaction between the 2 groups (prior vs no prior aspirin indication) was greater than .05.

Limitations

Some limitations should be recognized. The ARIES-HM3 trial included few patients with very recent PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD limiting power to claim noninferiority of an aspirin avoidance strategy in that subpopulation. Although clinical caution in using our results in such a population is advised, we do draw attention to the fact that the unique rheology of LVADs with development of an acquired von Willebrand disease in combination with use of VKA targeted to an INR of 2 to 3 may modify the need for antiplatelet therapy use even among those with recent instances of PCI, CABG, or acute myocardial infarction. Several studies in patients who were not treated with an LVAD have documented that aspirin can be safely deferred in patients with atrial fibrillation, and appropriate treatment with VKA or DOAC late after PCI22 or in patients with chronic coronary syndrome23 may not require use of antiplatelets for longer than 30 days after the event. Another limitation of the study is the fact that the results cannot be extrapolated beyond the 24-month analysis time of the ARIES-HM3 trial. Reassuringly, the results do not indicate a time-dependent effect of aspirin vs placebo on the primary end point. Furthermore, whether or not patients in follow-up who are supported with an HM3 LVAD and have received long-term aspirin treatment should undergo aspirin removal cannot be answered from our trial because this group was not studied. It should be emphasized that the results of the ARIES-HM3 trial, including those obtained in the current subgroup analysis, apply to patients treated with a VKA with a target INR between 2.0 and 3.0. The TTR for the 2 subgroups in the current study was 54% and 55%, and TTRs lower than this range may be associated with a different response to aspirin avoidance.24 Small successful studies replacing VKA with DOACs in selected patients implanted with an HM3 have been reported and larger studies are under way.25,26 It will be important from these studies to learn if aspirin can be avoided in DOAC-based protocols as well and also in individuals with a classical indication for aspirin, as described in the current study. Finally, the results apply only to the fully magnetically levitated centrifugal pump HM3 and cannot be extrapolated to other pumps with different engineering characteristics.

Conclusions

Results of this prespecified analysis of the ARIES-HM3 randomized clinical trial demonstrate that in patients with advanced HF and classical indications for antiplatelet therapy use at the time of durable LVAD implantation, aspirin avoidance (but with background use of VKA) was safe and not associated with increased thrombosis risk. Importantly, elimination of aspirin was associated with a large reduction in nonsurgical bleeding events in patients with a history of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD. Thus, the presence of these clinical conditions should not compel physicians to use aspirin as part of the antithrombotic regimen after LVAD implantation with the fully magnetically levitated HM3 LVAD.

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix. Patients Excluded Due to Investigator-Mandated Antiplatelet Therapy

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics

eTable 2. Medical History

eTable 3. Demographic Characteristics—Placebo vs Aspirin

eTable 4. Medical History—Placebo vs Aspirin

eTable 5. Baseline Laboratory Values Stratified by Previous History of PCI, CABG, Stroke or PVD

eTable 6. Baseline Hemodynamics Stratified by Previous History of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD

eTable 7. Cases of Multiple Aspirin Indications

eTable 8. P2Y12 Agents Use Prior LVAD Implant

eTable 9. Patient With Indication Within 12 Months From HM3 Implant

Nonauthor Collaborators. ARIES Investigators

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364-e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):407-477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries Endorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(9):763-816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. ; ACC/AHA Task Force Members . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):e344-e426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(38):3720-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. ; Writing Committee Members . 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVore AD, Mi X, Thomas L, et al. Characteristics and treatments of patients enrolled in the CHAMP-HF Registry compared with patients enrolled in the PARADIGM-HF trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(12):e009237. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madelaire C, Gislason G, Kristensen SL, et al. Low-dose aspirin in heart failure not complicated by atrial fibrillation: a nationwide propensity-matched study. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(2):156-167. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolfo D, Lund LH, Benson L, et al. Real-world use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: data from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(9):1648-1658. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. ; Authors/Task Force Members; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):4-131. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(17):e263-e421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehra MR, Cleveland JC Jr, Uriel N, et al. ; MOMENTUM 3 Investigators . Primary results of long-term outcomes in the MOMENTUM 3 pivotal trial and continued access protocol study phase: a study of 2200 HeartMate 3 left ventricular assist device implants. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(8):1392-1400. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC, et al. Five-year outcomes in patients with fully magnetically levitated vs axial-flow left ventricular assist devices in the MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial. JAMA. 2022;328(12):1233-1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitto JD, Shaw S, Garbade J, et al. Fully magnetically centrifugal left ventricular assist device and long-term outcomes: the ELEVATE registry. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(8):613-625. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorde UP, Saeed O, Koehl D, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2023 annual report: focus on magnetically levitated devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;117(1):33-44. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2023.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal A, Uriel N, Colombo PC, et al. Effects of a fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow or axial-flow left ventricular assist device on von Willebrand factor: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(8):806-816. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klovaite J, Gustafsson F, Mortensen SA, Sander K, Nielsen LB. Severely impaired von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet aggregation in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (HeartMate II). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(23):2162-2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehra MR, Netuka I, Uriel N, et al. ; ARIES-HM3 Investigators . Aspirin and hemocompatibility events with a left ventricular assist device in advanced heart failure: the ARIES-HM3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(22):2171-2181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.23204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehra MR, Crandall DL, Gustafsson F, et al. Aspirin and left ventricular assist devices rationale and design for the international randomized, placebo-controlled, noninferiority ARIES HM3 Trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;23(7):1226-1237. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kormos RL, Antonides CFJ, Goldstein DJ, et al. Updated definitions of adverse events for trials and registries of mechanical circulatory support: a consensus statement of the mechanical circulatory support academic research consortium. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(8):735-750. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starling RC, Blackstone EH, Smedira NG. Increase in left ventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1465-1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1401768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. ; RE-DUAL PCI Steering Committee and Investigators . Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1513-1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, et al. ; AFIRE Investigators . Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1103-1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammer Y, Xie J, Yang G, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding following Heartmate 3 left ventricular assist device implantation: the Michigan Bleeding Risk Model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2024;43(4):604-614. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2023.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Netuka I, Tucanova Z, Ivak P, et al. A Prospective randomized trial of direct oral anticoagulant therapy with a fully magnetically levitated LVAD: the DOT-HM3 study. Circulation. 2024;150(6):509-511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah P, Looby M, Dimond M, et al. Evaluation of the hemocompatibility of the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban in left ventricular assist devices: the DOAC LVAD study. JACC Heart Fail. 2024;12(9):1540-1549. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2024.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix. Patients Excluded Due to Investigator-Mandated Antiplatelet Therapy

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics

eTable 2. Medical History

eTable 3. Demographic Characteristics—Placebo vs Aspirin

eTable 4. Medical History—Placebo vs Aspirin

eTable 5. Baseline Laboratory Values Stratified by Previous History of PCI, CABG, Stroke or PVD

eTable 6. Baseline Hemodynamics Stratified by Previous History of PCI, CABG, stroke, or PVD

eTable 7. Cases of Multiple Aspirin Indications

eTable 8. P2Y12 Agents Use Prior LVAD Implant

eTable 9. Patient With Indication Within 12 Months From HM3 Implant

Nonauthor Collaborators. ARIES Investigators

Data Sharing Statement.