Abstract

Introduction

The Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living (FARS-ADL) is a validated and highly utilized measure for evaluating patients with Friedreich Ataxia. While construct validity of FARS-ADL has been shown for spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), content validity has not been established.

Methods

Individuals with SCA1 or SCA3 (n = 7) and healthcare professionals (HCPs) with SCA expertise (n = 8) participated in qualitative interviews evaluating the relevance, clarity, and clinical meaningfulness of FARS-ADL for assessment of individuals with SCA. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed by ATLAS.Ti v22 software.

Results

FARS-ADL concepts most frequently reported by individuals with SCA were difficulty walking (n = 7/7), falls (n = 6/7), speech difficulties (n = 4/7), and swallowing (n = 3/7). Individuals with SCA reported that all FARS-ADL items were relevant; Gait and Walking (n = 7/7), Bladder Function (n = 6/7), and Falling (n = 6/7) were considered extremely relevant. All HCPs (n = 8/8) reported that most FARS-ADL items were relevant to individuals with SCA; Quality of Sitting Position was considered least relevant. HCPs reported meaningful change as 1–2 point score change in individual FARS-ADL items (n = 7/7), 1–3 point change in total score (n = 6/6), and stability on any item and/or total score over ≥ 1 year, depending on SCA subtype (n = 5/8). Cognitive debriefing supported clarity and comprehension of FARS-ADL. Suggested improvements included refining response options for Dressing, Falling, Walking, and Bladder Function items.

Conclusion

The findings confirm the content validity of most FARS-ADL items for use in individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3, and offer suggested improvements for response options.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-024-00704-8.

Keywords: Content validity, Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale, FARS-ADL, Spinocerebellar ataxia

Key Summary Points

| While the Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living (FARS-ADL) is widely used to evaluate the functional disability of individuals with Friedreich ataxia, the content validity of FARS-ADL items in the context of other cerebellar ataxias, namely spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), is yet to be established. |

| By conducting qualitative interviews with individuals with SCA and healthcare professionals (HCPs) who treat ataxia, we gained insight into the signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA, and evaluated whether the items comprising the FARS-ADL are relevant and clinically meaningful measures for assessment of SCA disease progression. |

| The FARS-ADL was regarded as a useful, relevant, and easy to implement assessment that could detect clinically meaningful change and/or stability in SCA disease progression; however, there were suggestions for improvements in the response options for some items. |

| The findings support the content validity of most FARS-ADL items for assessing functional decline in SCA, and suggest that the instrument may serve as a relevant clinical trial endpoint to evaluate the efficacy of new therapies in individuals with SCA. |

Introduction

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a group of autosomal-dominantly inherited, progressive neurodegenerative disorders characterized by cerebellar degeneration [1]. While the approximately 50 SCA subtypes are clinically heterogeneous, the core triad of symptoms patients typically present with includes gait ataxia and incoordination, nystagmus or visual problems, and dysarthria [2, 3]. These symptoms usually manifest in mid-adulthood (from 30 to 50 years old), but can appear in childhood or in older adults (over 50 years old), depending on the causal genetic mutation [4]. Polyglutamine-encoding CAG repeat expansions in respective genetic loci cause the majority of the most common SCA subtypes (SCA1, 2, 3, and 6) [1]; however, biallelic pentanucleotide repeat expansion in the RFC1 [5] gene and intronic GAA repeat expansion in the FGF14 (SCA27b) gene have recently been identified as among the most common causal genetic mutations of late-onset cerebellar ataxia [6, 7].

The progression of symptoms through the disease trajectory has been shown to limit patients’ activities of daily living (ADLs) [8], substantially impact health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [9, 10], and contribute to early mortality [11, 12]. Clinical outcome assessments (COAs) have been used in natural history studies to evaluate the long-term progression of ataxia signs and symptoms, as well as to identify factors influencing speed of progression, across different SCA subtypes [13–15]. COAs that quantify patients’ functional independence provide fundamental insights into the impact of the disease on the lives of patients and may meaningfully reflect the wide-ranging disabilities associated with SCA [16]. A more comprehensive evaluation of how and when functional decline occurs during the SCA disease trajectory may also serve as a relevant clinical trial endpoint to assess the efficacy of new therapies in patients with SCA.

The Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living (FARS-ADL) is a validated and highly utilized clinician-rated COA for assessing functional disability in patients with Friedreich ataxia (FA) [17, 18]. The FARS-ADL consists of nine items: Speech, Swallowing, Cutting Food and Handling Utensils, Dressing, Personal Hygiene, Falling, Walking, Quality of Sitting Position, and Bladder Function. Items are rated on a scale from 0 to 4, in which lower scores represent “normal” function and higher scores represent greater functional disability [17]. Recent studies have evaluated the construct validity, sensitivity to change, and thresholds for meaningful change of the FARS-ADL in the context of cerebellar ataxias [19, 20]. While these studies have provided valuable insights into how the FARS-ADL may be used to assess patient-meaningful impairment across genetic ataxias, the content validity of FARS-ADL items for individuals with SCA has not yet been established.

Here, we report the results of qualitative interviews from individuals with mild-to-moderate CAG repeat expansion SCA subtypes and from healthcare professionals (HCPs) with expertise in treating SCA, which were conducted to assess the content validity of the FARS-ADL. Concepts exploring what may constitute clinically meaningful changes in SCA functional disabilities from a patient and HCP perspective when evaluating treatments are also reported.

Methods

Study Design

For a comprehensive overview of the methodology, please refer to Potashman et al. [21]. Briefly, qualitative interviews were conducted with individuals with CAG repeat expansion SCA subtypes in the United States and with HCPs who have experience treating SCA in the United States and Europe. Interviews evaluated the perspectives of individuals with SCA and HCPs on the FARS-ADL in terms of comprehensiveness, content validity, item relevance, and ability to measure meaningful changes in signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA. Interviews consisted of a concept elicitation phase (open discussion followed by a set of probes) and cognitive debrief (HCPs only) [21].

Participants

Study eligibility criteria for individuals with SCA and HCPs, and sample size information, are reported in Potashman et al. [21]. Eligible individuals aged 18–75 years with genetic confirmation of CAG repeat expansion SCA subtypes (SCA1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, or 10) were recruited via clinician referral or self-referral from the National Ataxia Foundation. HCPs from both the United States and Europe were identified for the interviews. All HCPs had extensive experience with COAs in SCA.

Interview Process

Interviews with individuals with SCA and HCPs were semi-structured and conducted in English via video call over 1–2 sessions. Discussion guides with questions focused on symptoms and impacts associated with SCA were developed for the concept elicitation phase. Interviews also included questions evaluating two other COAs used to assess SCA: the Modified Functional Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (f-SARA) [21] and the Patient Impression of Function and Activities Scale (PIFAS) (data not published).

The interview process is described in Potashman et al., Supplementary Table 3 [21]. The open concept elicitation phase collected the perspectives of individuals with SCA and HCPs on how SCA symptoms impact daily functioning. Open concept elicitation was followed by a set of previously identified probes [14, 22] designed to acquire additional information on the SCA symptoms that HCPs regarded as most common [14, 22]. Following HCP concept elicitation, cognitive debrief was conducted to assess the understandability, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the FARS-ADL in the context of SCA, following established methods [23]. Meaningful changes in the context of the FARS-ADL and the relevance of specific symptoms impacting individuals with SCA were also explored during the HCP interviews.

Sample Size

The low prevalence of SCA in the general population often only allows for small patient sample sizes. Consequently, the data presented in the current study are a supplement to previous work conducted by Schmahmann et al. [22] and Potashman et al. [14]. Data from the current study, together with the rich SCA concept library developed from the patient survey data [22], were used to establish saturation of disease concepts reported by individuals with SCA. This approach may be considered acceptable to verify the content validity of the FARS-ADL in a small sample of individuals with SCA.

Data Analysis

A descriptive content analysis was used to identify concepts from the interviews with individuals with SCA and HCPs. Interviews were audio recorded then transcribed, and transcripts were anonymized and coded with ATLAS.Ti v22 software. The frequency and relevance of concepts reported during the interviews was evaluated. Following established methods [24], and based on previously published data [14, 22], two codebooks were developed for analyzing the interview transcripts: one for individuals with SCA and one for HCPs. Transcripts were reviewed by multiple coders to minimize bias. Data collected during the concept elicitation phase from individuals with SCA were assessed for conceptual saturation [21]. Cognitive debrief analyses were conducted to assess understanding and relevance of the instructions, the recall period, items, and the response options of the FARS-ADL scale [23].

Ethical Considerations

The study (BHV-4157-SCA-VAL) was approved by a centralized independent institutional review board (Salus Institutional Review Board, Austin, TX, USA) on July 15, 2022. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the interviews and could withdraw at any time. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Participant Demographics and Characteristics

Overall, 7 individuals [42.9% female; mean (range) age, 51 (34–65) years] from the United States with genetically confirmed SCA (SCA1, n = 1; SCA3, n = 6) participated in the interviews (Table 1). Most individuals with SCA (n = 6/7; 85.7%) had mild-to-moderate symptoms and reported gait difficulties and/or requiring a walking aid/help to walk. Eight neurologists [n = 5 from the United States (HCPs 1–5); n = 3 from Europe (HCPs 6–8)] with expertise in treating individuals with SCA were recruited from ataxia centers of excellence.

Table 1.

Summary of demographics and clinical characteristics for individuals with SCA1 and SCA3

| Characteristics | Total (N = 7) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, years | |

| Mean (range) | 51 (34–65) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 4 (57.1) |

| Female | 3 (42.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Asian | 2 (28.6) |

| White | 4 (57.1) |

| Black or African American | 1 (14.3) |

| Work status, n (%) | |

| Working full time | 5 (71.4) |

| Retired | 1 (14.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| SCA diagnosis, n (%) | |

| SCA3 | 6 (85.7) |

| SCA1 | 1 (14.3) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |

| Mean (range) | 44 (31–56) |

| Diagnosis type (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | |

| Genetic testing | 7 (100.0) |

| Family historya | 6 (85.7) |

| Clinical/medical/other diagnosisa | 5 (71.4) |

| Severity of SCA, n (%) | |

| Stage 0 (no gait/walking difficulties) | 1 (14.3) |

| Stage 1 (gait difficulties but can walk) | 0 (0) |

| Between Stage 1 (gait difficulties but can walk) and Stage 2 (cannot walk without permanent use of a walking aid/help) | 4 (57.1) |

| Stage 2 (cannot walk without permanent use of a walking aid/help) | 1 (14.3) |

| Stage 3 (in a wheelchair) | 1 (14.3) |

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License from Potashman et al. [21]. Educational level of patients removed from the table presented here

SCA spinocerebellar ataxia

aAll individuals with a family history and/or a clinical/medical/other diagnosis also indicated genetic testing diagnosis

Relevance of FARS-ADL Concepts for Assessment of SCA

Perspectives from Individuals with SCA

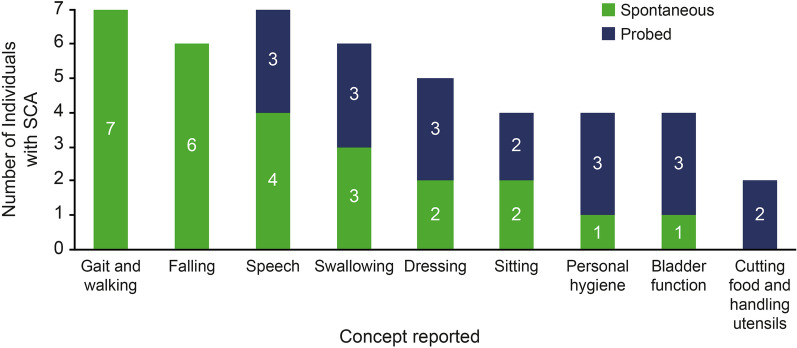

When individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 were asked to spontaneously report the signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA in their daily lives, the most frequently reported FARS-ADL concepts were difficulties with walking (n = 7/7; 100.0%), falls (n = 6/7; 85.7%), speech difficulties (n = 4/7; 57.1%), and swallowing (n = 3/7; 42.9%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of FARS-ADL concepts discussed in interviews with individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3. FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, SCA spinocerebellar ataxia

Participant 1 described the aspects of everyday life that are most affected by SCA: “It’s kind of hard to say what’s more affected than what’s not affected, because it touches every single part of life. But I’d say just basic walking.”

Concepts frequently reported spontaneously by individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 that are not included on the FARS-ADL were difficulties working (n = 5; 71.4%), challenges with social life (n = 5; 71.4%), difficulties driving (n = 4; 57.1%), and emotional dysfunction (n = 4; 57.1%). For a complete overview of the concept elicitation findings, refer to Potashman et al. [21].

When asked to report the FARS-ADL items that were relevant, individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 indicated that the Gait and Walking (Item 7; n = 7/7), Speech (Item 1; n = 7/7), Dressing (Item 4; n = 5/7), Personal Hygiene (Item 5; n = 4/7), Falling (Item 6; n = 4/7), and Bladder Function (Item 9; n = 4/7) items were of particular importance for assessing the impact of their SCA. The Swallowing item (Item 2) was partially supported as relevant; some concepts included in the item (i.e., choking) were reported by most individuals (n = 5/7), whereas other concepts (i.e., avoids certain foods) were not reported by any. The Quality of Sitting Position item (Item 8) was considered relevant by a proportion of individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 (n = 3/7). The Cutting Foods and Handling Utensils item (Item 3) was considered the least relevant item on the FARS-ADL by participating individuals (n = 2/7).

When asked to rate the relevance of items covered by the FARS-ADL using a 5-point rating scale (0 = “not at all relevant” to 4 = “extremely relevant”), each item was reported as being relevant by all individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 (n = 7/7) (each concept ≥ 1 [a little relevant]). Gait and Walking (n = 7/7; median score of 4), Bladder Function (n = 6/7; median score of 4), and Falling (n = 6/7; median score of 3) received the highest scores and were considered “extremely relevant” (Table 2). The Speech (n = 6/7), Swallowing (n = 6/7), and Quality of Sitting Position (n = 7/7) items all had a median score of 2, reflecting that they were considered “somewhat relevant” to individuals with SCA1 and SCA3. The remaining FARS-ADL items (Cutting Food and Handling Utensils, Dressing, and Personal Hygiene) had a median score of 1, reflecting that they were considered “a little relevant.”

Table 2.

Relevance of FARS-ADL items from the perspective of individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3

| Item | Number of individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 reporting item is relevant (n = 7), n (%) | Relevance rating by patient, from 0 (not at all relevant) to 4 (extremely relevant) | Median relevance rating | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | |||

| Speech | 6 (85.7) | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Swallowing | 6 (85.7) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3–4 | 4 | 2 |

| Cutting Food and Handling Utensils | 6 (85.7) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0–1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Dressing | 6 (85.7) | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Personal Hygiene | 5 (71.4) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Falling | 6 (85.7) | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Walking | 7 (100.0) | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Quality of Sitting Position | 7 (100.0) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1–2 | 3 | 2 |

| Bladder Function | 6 (85.7) | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, P participant, SCA spinocerebellar ataxia

Perspectives from HCPs

For a complete overview of the HCP concept elicitation findings refer to Potashman et al. [21]. Concepts spontaneously elicited by HCPs were mapped against the items included on the FARS-ADL to evaluate the conceptual coverage (i.e., comprehensiveness) of the instrument for assessment of individuals with SCA (Table 3). When asked about the relevant signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA for tracking disease progression, all 8 HCPs (100.0%) reported difficulties with gross motor functions (gait, stance, balance, and walking), fine motor skills (e.g., writing, buttoning, using cutlery), and speech. Each of these concepts are assessed, or partially assessed, by items included on the FARS-ADL; gross motor function is captured in Items 6 (Falling) and 7 (Walking), fine motor skills are captured in Items 3 (Cutting Food and Handling Utensils) and 4 (Dressing); and speech is captured in Item 1 (Speech).

Table 3.

HCP interview concept mapping to the FARS-ADL

| Concept (spontaneously reported) | HCPs reporting concept (N = 8), n (%) | FARS-ADL item |

|---|---|---|

| Gross motor | ||

| Difficulty with general mobility | 5 (62.5) | Walking (Item 7) |

| Difficulty walking | 8 (100.0) | Walking (Item 7) |

| Balance | 6 (75.0) | Walking (Item 7) |

| Difficulty standing | 4 (50.0) | – |

| Falling | 6 (87.5) | Falling (Item 4) |

| Physical function | ||

| Speech | 8 (100.0) | Speech (Item 1) |

| Vision problems | 5 (62.5) | – |

| Dizziness | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Fatigue | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Swallowing | 4 (50.0) | Swallowing (Item 2) |

| Difficulty turning | 1 (12.5) | – |

| Tremor | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Nystagmus | 1 (12.5) | – |

| Hand coordination | 4 (50.0) | Cutting Food and Handling Utensils (Item 3) |

| Fine motor accuracy | 8 (100.0) | Cutting Food and Handling Utensils (Item 3) |

| ADLs | ||

| Difficulty getting dressed | 3 (37.5) | Dressing (Item 4) |

| Difficulty eating/drinking | 4 (50.0) | Swallowing (Item 2) |

| Difficulty getting up | 1 (12.5) | - |

| Difficulty going to the bathroom | 1 (12.5) | Personal Hygiene (Item 5) |

| Utilizing assistive devices | 4 (50.0) | Falling (Item 6); Walking (Item 7) |

| Need someone’s help/loss of independence | 5 (62.5) | – |

| Personal hygiene | 1 (12.5) | Personal Hygiene (Item 5) |

| Emotional/cognitive function | ||

| Impacted mood | 3 (37.5) | – |

| Impacted cognition | 3 (37.5) | – |

| Physical function | ||

| Difficulty using electronics | 3 (37.5) | – |

| Poor handwriting | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Difficulty performing kitchen activities | 3 (37.5) | Cutting Food and Handling Utensils (Item 3) |

| Difficulty running | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Trouble reading | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Difficulty driving | 2 (25.0) | – |

| Relationships with others | ||

| Difficulty communicating | 8 (100.0) | Speech (Item 1) |

| Impacted family life | 3 (37.5) | – |

| Impacted participation in family events | 3 (37.5) | – |

| Impacted work status/abilities | 5 (62.5) | – |

Items in italics represent partial matches to concepts

– indicates concept not included on FARS-ADL

ADL activities of daily living, FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, HCP healthcare professional

HCP2 described the signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA: “It affects all aspects of daily life: difficulty walking, difficulty in speaking, to be understood, and dexterity problems, and movement problems.”

Concepts frequently reported by HCPs but not included on the FARS-ADL included vision problems (n = 5; 62.5%), loss of independence (n = 5; 62.5%), impacted employment status (n = 4; 50.0%), difficulties using electronics (n = 3; 37.5%), impacted cognition (n = 3; 37.5%), and emotional dysfunction (n = 3; 37.5%). While Sitting and Bladder Function are included as items on the FARS-ADL, neither were spontaneously mentioned by any of the HCPs.

HCP5 described the signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA: “Because it can be such a severe disease, they have tremendous loss of income. So, these are patients who are not able to be, generally speaking, gainfully employed.”

When asked about FARS-ADL items, all HCPs (n = 8/8) agreed that most items included on the instrument were relevant to individuals with SCA (Table 4). HCPs considered the Walking (n = 8/8), Falling (n = 8/8), Dressing (n = 8/8), Speech (n = 7/7; 1 HCP not asked), Cutting Food and Handling Utensils (n = 7/7; 1 HCP not asked), and Swallowing (n = 6/6; 2 HCPs not asked) items the most relevant, while the Quality of Sitting Position item was considered relevant by the fewest number of HCPs (n = 6/8).

Table 4.

Relevance of items included on the FARS-ADL

| FARS-ADL item | HCP1 | HCP2 | HCP3 | HCP4 | HCP5 | HCP6 | HCP7 | HCP8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1: Speech | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y |

| Item 2: Swallowing | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A |

| Item 3: Cutting Food and Handling Utensils | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y |

| Item 4: Dressing | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 5: Personal Hygiene | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 6: Falling | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 7: Walking | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 8: Quality of Sitting Position | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 9: Bladder Function | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, HCP healthcare professional, N/A not asked, N no, Y yes

HCP4 described the relevance of FARS-ADL items: “Speech is relevant because it’s something that everybody needs to do.”

HCP3 described the relevance of FARS-ADL items: “The quality of the sitting position tends to be less relevant (…) I think most of the time, people just – if they do have problems with sitting, they just sit in chairs with backs.”

Defining Clinically Meaningful Change and Stability in SCA Using the FARS-ADL

Perspectives from HCPs

When asked about what changes in FARS-ADL item level score may constitute meaningful improvement, all HCPs (n = 7/7; 1 HCP not asked) reported that a 1- to 2-point change in an individual item would be meaningful (Table 5). Meaningful worsening and improvement at the item level were both independently reported as a 1- to 2-point change by all HCPs [worsening, n = 8/8; improvement, n = 7/7 (1 HCP not asked)]. Most HCPs (n = 6/8) considered a change (worsening or improvement) of 1–2 points meaningful regardless of the FARS-ADL item being measured. Conversely, 2 HCPs (n = 2/8) gave more weight to specific FARS-ADL items and noted that meaningful change would be dependent on the specific item being measured and the baseline severity of the individual’s function. Two HCPs suggested that for specific items, a change on the item level score from 2 to 3 would be more meaningful than a change from 1 to 2 (Speech, Cutting Food and Handling Utensils, Personal Hygiene, Quality of Sitting Position, and Bladder Function items).

Table 5.

HCP reported meaningful change on the FARS-ADL

| HCP ID | Meaningful improvement | Meaningful worsening | Reported meaningful change threshold applicable to all FARS-ADL items | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item score | Total score | Item score | Total score | ||

| HCP1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y |

| HCP2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Y |

| HCP3 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | N |

| HCP4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Y |

| HCP5 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | Y |

| HCP6 | 1–2 | N/A | 1–2 | 1–2 | N |

| HCP7 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 | Y |

| HCP8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Y |

FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, HCP healthcare professional, ID identification, N/A not asked, N no, Y yes

For the FARS-ADL total score, clinically meaningful improvement ranged from a 1- to 3-point improvement in total score (n = 5/5; 3 HCPs not asked) (Table 5). For meaningful worsening, the majority of HCPs considered that a worsening of 1–2 points in FARS-ADL total score would be meaningful (n = 5/6; 2 HCPs not asked). A 3-point improvement or worsening in FARS-ADL total score was regarded as clinically meaningful by one HCP.

HCP6 described what changes may be considered meaningful improvement at the FARS-ADL item score level: “A plus 2 improvement would for sure be meaningful. And that could be in any of those items it will be meaningful, and in any of the scoring parts of those items, because that’s a really big, big step. Whether a point one improvement would be important depends on the item and the relative scoring of the item.”

HCP1 described what changes may be considered meaningful worsening at both the FARS-ADL total and item score level: “If they worsened by one point on any of the subscales, it’s a clear difference from where they were to where they are now.”

HCP7 described what changes may be considered meaningful improvement at the FARS-ADL total score level: “One point of improvement in the total score or stability in the total score over 48 weeks.”

When asked what would be considered meaningful stability in FARS-ADL scores, most HCPs reported that no change in an item score (n = 7/8) or the total score (n = 5/8) over a 1- to 2-year period would be meaningful (Table 6). For those HCPs who did not consider “no change” in total score over 1–2 years to be meaningful, most (n = 2/3) suggested a longer time period would be necessary, explaining that there would not typically be an expected change to FARS-ADL score over a 48-week period with the natural history of SCA, particularly in the context of those individuals who do not present with CAG repeat expansion SCA subtypes.

Table 6.

HCP reported meaningful stability on the FARS-ADL

| HCP ID | Stability considered as meaningful | Duration required for meaningful stability | Stability meaningful for all FARS-ADL items |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCP1 | Y | 1 year | Y |

| HCP2 | Y | 1 year | Y |

| HCP3 | Y | 1 year | Y |

| HCP4 | Y | 2 years | Y |

| HCP5 | Y | 1 year | Y |

| HCP6 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HCP7 | Y | 48 weeks | Y |

| HCP8 | N | N/A | N |

FARS-ADL Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale–Activities of Daily Living, HCP healthcare professional, ID identification, N/A not asked, N no, Y yes

Describing what may be considered meaningful stability in terms of the FARS-ADL score, HCP3 said: “Because we expect these patients to get worse over time, the fact that if someone does not get worse over time, that’s actually a huge deal. And so, I would say if over the course of 2 years, everything is the same, well, that’s actually really meaningful.”

Similarly, HCP7 stated: “For those [with] SCA, at least 2 years, so 96–102 for weeks. Maybe 3 years.”

Regarding meaningful stability with prescription of a drug, the majority of HCPs (n = 6/8) reported that no change in FARS-ADL score for 1 year would be meaningful. For the remaining two HCPs who did not consider “no change” in total score over 1–2 years as meaningful, they elaborated that no change over 2 or 3 years would be considered meaningful, particularly in individuals with CAG repeat expansion SCA subtypes.

HCP1 described what may be considered meaningful stability with prescription of a drug in terms of FARS-ADL score: “If they can get through a year on a particular treatment and stayed the same, that would be meaningful.”

FARS-ADL Cognitive Debrief

A cognitive debrief of the components of the FARS-ADL was performed. HCPs were asked about the general ease of understanding of instructions, their interpretation of the instructions, and the clarity of each item and response option. Overall, all HCPs (n = 8/8) were familiar with the FARS-ADL and interpreted the instrument instructions correctly (Supplementary Material). Most response options were interpreted as intended, and HCPs described them as easy to understand; however, three HCPs (n = 3/8) reported that the response options for the Walking item (Item 7) required further clarification because it was difficult to differentiate between the different scoring categories. The basis of response selection varied among HCPs, but most indicated that patient and/or caregiver input was considered with evaluation of each FARS-ADL item.

For scoring, the FARS-ADL scoring scale includes the option of adding 0.5 increments on each item, which may be applied if the HCP feels that an individual’s performance on an item falls between two scores. When asked, all HCPs (n = 8/8) stated that they would rarely (if ever) use the 0.5 score increment because the scoring categories within the FARS-ADL item scores were distinct enough.

HCP1 described the use of the 0.5 increment score on the FARS-ADL: “I don’t use the 0.5 increment, because I think it blurs the difference between two very clear levels. ‘No difficulty being understood; sometimes asked to repeat statements.’ Admittedly, ‘sometimes’ is a little vague, but adding a half point in there is going to make it even vaguer. You know, I think the half point takes away the meaningfulness of these different reporting activities.”

FARS-ADL Clinical Impressions

When asked what they liked and disliked about the FARS-ADL, most HCPs reported that the instrument was useful and easy to use. Suggestions for improvements included the need for clearer instructions for the Quality of Sitting Position item (Item 8), particularly because sitting difficulties were not seen as a problem for individuals with SCA until the very advanced stages of the disease; clarification of response options for the Dressing (Item 4), Falling (Item 6), Walking (Item 7), and Bladder Function (Item 9) items because impairment levels were difficult to categorically distinguish; and clarification on how to account for an individual’s accent in speech assessment. Some HCPs noted that concepts such as pain (n = 1/8), cognitive function (n = 1/8), and visual impairment (n = 1/8) may be missing from the FARS-ADL to make it a more comprehensive measure of ADLs.

HCP4 described their overall impression of the FARS-ADL for clinical evaluation of individuals with SCA: “I think what I like about it is it’s pretty thorough and covers a variety of different things that people do in day-to-day life that would not necessarily be discussed by the patient or documented in any other way.”

HCP1 described the ease of response selection for the Walking item on the FARS-ADL: “I think levels 1, 2, and 3 need some clarification. So, I don’t think it’s 100% easy to get a reproducible and exact scoring for walking.”

Discussion

Validated COAs that objectively measure the relevant signs, symptoms, and impacts of SCA are important tools to assess the potential efficacy of new treatments. This qualitative interview study evaluating the content validity of the FARS-ADL for use in SCA demonstrates that this instrument is regarded as a useful and relevant outcome measure to assess disease progression in individuals with SCA. All HCPs interviewed agreed that most items included on the FARS-ADL were relevant to individuals with SCA, with the Walking, Falling, Speech, and Swallowing items considered most relevant. Similarly, individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 considered the Gait and Walking, Bladder Function, and Falling items extremely relevant. Overall, HCPs indicated that clinically meaningful change on the FARS-ADL would be a 1- to 2-point improvement or worsening over 1 year or stabilization in score over a 1-year period; however, this was dependent on SCA subtype. HCPs confirmed that the FARS-ADL instrument was understandable, interpretable, and easy to use. The findings support the content validity and clinical meaningfulness of the FARS-ADL to evaluate the disease progression of individuals with SCA.

While most concepts included on the FARS-ADL were considered relevant by HCPs, there were varied reports on the relevance of the Quality of Sitting Position item. HCPs indicated that the ability to sit may not be impacted by SCA, or that issues with sitting only occur with very advanced disease and, consequently, the Quality of Sitting Position item was not particularly relevant for most patients assessed in the clinic. This was consistent with the data previously published on the content validity of the f-SARA [21]. Similarly, individuals with mild-to-moderate SCA1 and SCA3 also reported that the Quality of Sitting Position item was only somewhat relevant.

Concepts that were reported as relevant by both individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 and HCPs, but that are not measured on the FARS-ADL, were primarily centered around HRQoL indicators and included difficulties working, loss of independence (such as driving), and emotional dysfunction. This suggests that instruments measuring HRQoL outcomes may complement well-established clinical instruments such as FARS-ADL when evaluating SCA disease progression. HCPs also reported that individuals with SCA have difficulties with electronics; however, aspects of fine motor skills are assessed by the Cutting Foods and Handling Utensils and Dressing items on the FARS-ADL.

Interestingly, there was variability on the perception of the Cutting Foods and Handling Utensils and Bladder Function items observed across the interviews. The Cutting Foods and Handling Utensils item was not spontaneously reported by any of the individuals with SCA1 and SCA3, and was rated as the least relevant item on the FARS-ADL for tracking SCA disease progression. Conversely, all HCPs asked reported that the Cutting Foods and Handling Utensils item was valuable for assessing disease progression. For the Bladder Function item, none of the HCPs and only one individual with SCA spontaneously mentioned bladder issues during the concept elicitation phase of the interview. Despite this, individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 rated the Bladder Function item as ‘’extremely relevant’’ (median score of 4). For context, the Walking item was also given a median score of 4 by individuals with SCA, suggesting that the Bladder Function and Walking items are comparable in terms of everyday impact for individuals with SCA1 and SCA3. Furthermore, when HCPs were asked about the relevance of FARS-ADL items, Bladder Function was considered to be relevant by most HCPs (n = 7/8). The lack of spontaneous mention of issues with bladder function by most individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 and HCPs during the concept elicitation phase may be reflective of the sensitivity of the topic, or of the SCA disease stage in mind. For example, issues with bladder function may not have impacted a proportion of the individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 who identified as having mild symptoms at the time of interview. Despite this, those individuals may consider that the Bladder Function item will demonstrate increasing relevance with SCA disease progression.

Overall, HCPs reported that the items included on the FARS-ADL could detect clinically meaningful changes and stabilization of disease in individuals with SCA; however, the timeframes for this varied, depending on the progression rate of the underlying SCA. For example, SCA6 progresses more slowly than other SCA subtypes [13] based on the natural history of the disease, and longer timeframes with no detected FARS-ADL score changes would be required to accurately determine whether stabilization had been achieved in individuals with SCA6. Indeed, a recent study investigating the validity, clinical meaningfulness, and sensitivity to change of the FARS-ADL across genetic ataxias reported that the instrument was comparable to the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) for detecting meaningful changes at the item level and was sensitive to change at 1-year follow-up in individuals with SCA3 [20]. The study indicated that the FARS-ADL was markedly correlated to both clinician-reported outcomes (FARS-stage; SARA) and patient-reported outcomes (Patient-Reported Outcome Measure of Ataxia; European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions visual analogue scale), suggesting that it may be a valuable COA for assessing both clinician-reported disease severity and patient-meaningful impairment [20]. While the authors suggested that the FARS-ADL may be a valid 12-month trial endpoint for assessing patient-meaningful impairment across common ataxias (e.g., SCA3) in addition to FA, further studies are required to evaluate the instrument’s differential sensitivity and the temporal dynamics of the item and total scoring system for SCA genotypes with varying speeds of progression.

Though the focus of this study was to evaluate the content validity of the FARS-ADL in individuals with SCA, HCPs made several recommendations that may potentially improve the relevance of the FARS-ADL for all common genetic ataxia populations. Most suggestions focused on clarification of response options or instructions for particular items included on the instrument. HCPs also suggested the addition of items assessing pain, cognitive function, and visual impairment. As the majority of genetic ataxias result in a similar set of signs, symptoms, and impairments [20], implementation of the recommendations provided would likely further improve ADL measurement for individuals with FA, SCA, and other types of ataxia.

The data presented in the current study are largely consistent with those reported previously for individuals with cerebellar ataxia. In a study examining the relevance of FARS-ADL concepts for individuals with SCA, FA, and other ataxias, all FARS-ADL items could be mapped to multiple real-life examples of the disease experience [14, 22]. In addition, Traschutz et al. [20] highlighted the usefulness of the FARS-ADL as a valid COA for assessment of patient-relevant outcomes in individuals with SCA. These results, in conjunction with the findings reported here, show that the FARS-ADL reflects the patient voice and demonstrates relevance to individuals with SCA or cerebellar dysfunction.

Despite this, the current study has several limitations that require acknowledgment. Overall, the sample size of individuals with SCA was small, which prevented conceptual saturation from being reached during the concept elicitation phase of the interviews with individuals with SCA. However, as reported in Potashman et al. [21], most concepts reported by individuals with SCA reached saturation when considered alongside the qualitative patient survey data [14, 22]. Additionally, individuals with SCA were recruited via a patient advocacy organization in the United States, which may have introduced sample bias. Furthermore, as all individuals with SCA who participated in the interviews had either SCA3 or SCA1, the results of the study may have limited generalizability to the other approximately 50 SCA subtypes [3]. Finally, most individuals with SCA1 and SCA3 who participated in the interviews had mild-to-moderate disease, which limits the generalizability of the FARS-ADL content validity results to this disease stage only. Studies including participants with more advanced SCA may offer additional insights into the temporal relevance of FARS-ADL items as the disease progresses. This would be of particular interest for the FARS-ADL items that were rated as “a little relevant” (Cutting Food and Handling Utensils, Dressing, and Personal Hygiene) by individuals with mild-to-moderate disease.

Conclusions

The findings from the current study confirm the content validity of the FARS-ADL for use in individuals with SCA. The FARS-ADL was well understood by HCPs and easy to implement in the clinic. All HCPs confirmed that the FARS-ADL could detect clinically meaningful changes and/or stability in SCA disease progression. Several suggestions to enhance the clarity of item response options were provided, which may improve the validity of the FARS-ADL for individuals with SCA, FA, and other types of ataxia.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the individuals with SCA who participated in the interviews and the National Ataxia Foundation for supporting the identification of participants with SCA. The authors thank Alessandra Girardi, Audra Gold, and Kavita Jarodia of Parexel for their input on the study.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Laura Graham, PhD, of Parexel and was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Author Contributions

Michele Potashman, Melissa Wolfe Beiner, Gil L’Italien, and Vlad Coric contributed to study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection was performed by Katja Rudell, Naomi Suminski, Rinchen Doma, Maggie Heinrich, and Linda Abetz-Webb. Liana S. Rosenthal, Sheng-Han Kuo, Theresa Zesiewicz, Terry D. Fife, Bart van de Warrenburg, Giovanni Ristori, Matthis Synofzik, Sub Subramony, Susan Perlman, and Jeremy D. Schmahmann contributed to data synthesis. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors commented on the manuscript during development and approved the final version.

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Michele Potashman, Melissa Wolfe Beiner, Vlad Coric, and Gil L’Italien are employed by, and own shares in, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Katja Rudell, Naomi Suminski, Rinchen Doma, and Maggie Heinrich are employees of Parexel and were commissioned by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. to conduct the study. Sheng-Han Kuo, Theresa Zesiwicz, Bart van de Warrenburg, Liana S. Rosenthal, Terry D. Fife, Giovanni Ristori, Matthis Synofzik, and Susan Perlman received consultancy fees from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for participating in the interviews. Linda Abetz-Webb received consultancy fees from Parexel for this study. Sheng-Han Kuo has received consultancy fees from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Praxis Precision Medicines, and Sage Therapeutics. Liana S. Rosenthal receives salary support for her role as the site Principal Investigator for research studies with Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer, and EIP Pharma, and for serving on the Clinical Events Committee for a research study with functional neuromodulation. She also serves on the steering committees for the Parkinson Study Group’s research study with both UCB Pharmaceuticals and Bial Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Rosenthal also served on an advisory board for Reata Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Pharmaceuticals, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and as a one-time consultant for UCB Pharmaceuticals. Theresa Zesiwicz has received personal compensation for serving on the advisory boards of Boston Scientific, Reata Pharmaceuticals, and Steminent Biotherapeutics; and received personal compensation as senior editor for Neurodegenerative Disease Management and as a consultant for Steminent Biotherapeutics. Royalties: royalty payments as co-inventor of varenicline for treating imbalance and nonataxic imbalance. Grants: research grant support as Principal Investigator for studies from AbbVie, Biogen Pharmaceuticals, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Boston Scientific, Bukwang Pharmaceuticals, Cala Health, Cavion, Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance; Houston Methodist Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Retrotope, and Takeda Development Center Americas. Bart van de Warrenburg has served on advisory boards and/or as consultant for Servier, VICO Therapeutics, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and uniQure. Royalties: BSL—Springer Nature. Grants: Radboud University Medical Center, ZonMw, Gossweiler Foundation, Hersenstichting, NWO, and Christina Foundation. Jeremy D. Schmahmann has served on the Editorial Board for The Cerebellum since 1999. Consultancy: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Site Principal Investigator: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. clinical trials in ataxia and multiple system atrophy. Research support, commercial entities: Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. support of clinical trials. Research support, academic entities: National Ataxia Foundation. Research support, foundations, and societies: National Ataxia Foundation, 2019, Principal Investigator license fee payments. Technology or inventions: Brief Ataxia Rating Scale (BARS) and Brief Ataxia Rating Scale revised (BARS2), copyright held by The General Hospital Corporation; Cerebellar Cognitive Affective/Schmahmann syndrome Scale, copyright held by The General Hospital Corporation; Patient-Reported Outcome Measure of Ataxia, copyright held by The General Hospital Corporation; and Cerebellar Neuropsychiatric Rating Scale, copyright held by The General Hospital Corporation. Matthis Synofzik has received consultancy honoraria from Ionis, UCB Pharmaceuticals, Prevail, Orphazyme, Biogen Pharmaceuticals, Servier, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Gen-Orph, AviadoBio, Zevra, Lilly, and Solaxa, all unrelated to the present manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The study (BHV-4157-SCA-VAL) was approved by a centralized independent institutional review board (IRB; Salus Institutional Review Board, Austin, TX, USA) on 15 July 2022. IRB approval was not required for HCP interviews conducted in the United States or Europe. HCPs received consultancy fees for participating in the interviews. All eligible individuals with SCA and the HCPs provided informed consent to participate in the interviews and could withdraw at any time. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: These data were previously presented as a poster at the Muscular Dystrophy Association annual conference, March 3–6, 2024, Orlando, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Ghanekar SD, Kuo SH, Staffetti JS, Zesiewicz TA. Current and emerging treatment modalities for spinocerebellar ataxias. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22(2):101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan R, Yau WY, O’Connor E, Houlden H. Spinocerebellar ataxia: an update. J Neurol. 2019;266(2):533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobi H, Schaprian T, Schmitz-Hübsch T, et al. Disease progression of spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3 and 6 before and after ataxia onset. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2023;10(10):1833–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlman S. Hereditary ataxia overview. 1998. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1138/. Accessed May 16, 2024. [PubMed]

- 5.Sullivan R, Yau WY, Chelban V, et al. RFC1-related ataxia is a mimic of early multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(4):444–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilke C, Pellerin D, Mengel D, et al. GAA-FGF14 ataxia (SCA27B): phenotypic profile, natural history progression and 4-aminopyridine treatment response. Brain. 2023;146(10):4144–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengel H, Pellerin D, Wilke C, et al. As frequent as polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias: SCA27B in a large German autosomal dominant ataxia cohort. Mov Disord. 2023;38(8):1557–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz-Hübsch T, Coudert M, Giunti P, et al. Self-rated health status in spinocerebellar ataxia–results from a European multicenter study. Mov Disord. 2010;25(5):587–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber N, Buchholz M, Rädke A, et al. Factors influencing health-related quality of life of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum. 2024;23(4):1466–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchholz M, Weber N, Rädke A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia: a validation study of the EQ-5D-3L. Cerebellum. 2023;23(3):1020–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diallo A, Jacobi H, Cook A, et al. Survival in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, and 6 (EUROSCA): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(4):327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monin M-L, Tezenas du Montcel S, Marelli C, et al. Survival and severity in dominant cerebellar ataxias. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2(2):202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobi H, du Montcel ST, Bauer P, et al. Long-term disease progression in spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, and 6: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(11):1101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potashman MH, Mize ML, Beiner MW, Pierce S, Coric V, Schmahmann JD. Ataxia rating scales reflect patient experience: an examination of the relationship between clinician assessments of cerebellar ataxia and patient-reported outcomes. Cerebellum. 2023;22(6):1257–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CC, Ashizawa T, Kuo SH. Collaborative efforts for spinocerebellar ataxia research in the United States: CRC-SCA and READISCA. Front Neurol. 2020;11:902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz GCD, Zonta MB, Munhoz RP, et al. Functionality and disease severity in spinocerebellar ataxias. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022;80(2):137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Tsou AY, et al. Measuring Friedreich ataxia: complementary features of examination and performance measures. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1711–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman LS, Farmer JM, Perlman S, et al. Measuring the rate of progression in Friedreich ataxia: implications for clinical trial design. Mov Disord. 2010;25(4):426–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klockgether T, Synofzik M, Alhusaini S, et al. Consensus recommendations for clinical outcome assessments and registry development in ataxias: Ataxia Global Initiative (AGI) Working Group Expert Guidance. Cerebellum. 2024;23(3):924–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traschütz A, Fleszar Z, Hengel H, et al. FARS-ADL across ataxias: construct validity, sensitivity to change, and minimal important change. Mov Disord. 2024;39(6):965–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potashman M, Rudell K, Pavisic I, et al. Content validity of the modified functional Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (f-SARA) instrument in spinocerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum. 2024;23(5):2012–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmahmann JD, Pierce S, MacMore J, L’Italien GJ. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure of ataxia. Mov Disord. 2021;36(10):2367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 1–eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.