Abstract

Introduction

This analysis aimed to evaluate patient-related outcomes for health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and cognitive performance in patients (≥ 16 years) with focal-onset seizures (FOS), with/without focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, after initiating adjunctive brivaracetam (BRV) in routine clinical practice.

Methods

A 12-month, prospective, real-world, noninterventional study in nine European countries (EP0077/NCT02687711) was performed. BRV was prescribed per clinical practice and the European Summary of Product Characteristics. The outcomes evaluated were the Patient Weighted Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-Form 31 (QOLIE-31-P), the Clinical and the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (CGIC and PGIC, respectively), and EpiTrack®. EpiTrack® scores were categorized into cognitive performance categories (excellent: ≥ 39 points; average: 32–38 points; mildly impaired: 29–31 points; significantly impaired: ≤ 28 points). The change in EpiTrack® score was evaluated [improvement: increase in score of ≥ 4 points; no change: change in score of − 2 to 3 points (inclusive); worsening: change in score of at least − 3 points].

Results

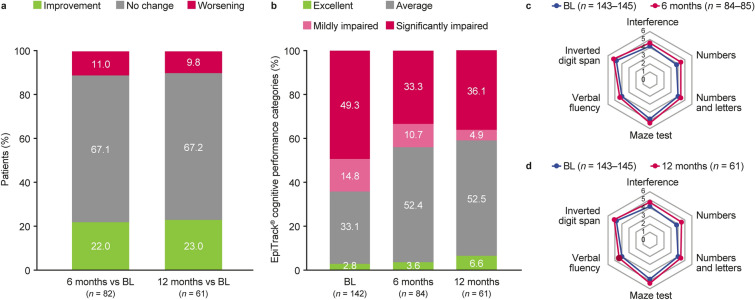

Full Analysis Set: 541 patients. 46.6% of patients reported a clinically meaningful improvement in QOLIE-31-P total score from baseline to 12 months; the mean change in total score was + 6.2 points (N = 103). Per CGIC (N = 142) and PGIC (N = 148), respectively, 69.0% and 62.8% of patients had improved in overall condition at 12 months versus baseline, while 3.5% and 8.1% had worsened. EpiTrack® categories at 12 months versus baseline showed improved cognitive performance [baseline (N = 142): significantly impaired 49.3%, mildly impaired 14.8%, average 33.1%, excellent 2.8%; 12 months (N = 61): significantly impaired 36.1%, mildly impaired 4.9%, average 52.5%, excellent 6.6%]. At 12 months, 67.2% of patients showed no significant change from baseline in EpiTrack® score, 23.0% had improved, and 9.8% had worsened (N = 61).

Conclusion

In patients with predominantly difficult-to-treat FOS, BRV add-on was associated with good HRQoL and cognitive functioning. Cognitive functioning remained stable for 12 months after BRV initiation in most patients; nearly one-quarter experienced significant improvements. At 12 months, 46.6% of patients reported clinically meaningful HRQoL improvements, and most showed an improved overall condition.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-024-00698-3.

Keywords: Brivaracetam, Cognitive performance, Epilepsy, EpiTrack, Focal-onset seizure, Noninterventional, Observational, Health-related quality of life, Real-world

Key Summary Points

| It is increasingly recognized that seizure control is only one aspect of comprehensive management of epilepsy: cognitive, physical, and psychological functioning factors all influence patients’ overall well-being and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and require comprehensive evaluation |

| This prospective, post-marketing, observational study in nine European countries aimed to evaluate patient-related outcomes for HRQoL and cognitive performance in patients aged ≥16 years with focal-onset seizures (FOS) initiating adjunctive brivaracetam (BRV) in routine clinical practice |

| In this patient population with predominantly difficult-to-treat FOS, at 12 months, 46.6% reported clinically meaningful HRQoL improvements and most showed improved overall condition |

| Cognitive functioning after initiating BRV remained stable for 12 months in most patients, and nearly a quarter of patients experienced significant improvements (measured by the EpiTrack® instrument) |

Introduction

Epilepsy can have a significant impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) due to profound adverse social, physical, and psychological consequences of the condition and its treatments [1]. Over the last few decades, increasing attention has been given to HRQoL evaluation in patients with epilepsy. Several studies have highlighted that patients with epilepsy report poorer HRQoL compared with the general population [2–4]. Factors associated with reduced HRQoL in adults with epilepsy include increases in seizure frequency and severity as well as levels of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance [5, 6]. Social stigma and discrimination can have an additional negative impact on HRQoL [7, 8].

Neuropsychological assessment is increasingly used to monitor epilepsy and its underlying pathologies, and can be applied to quality and outcome control of pharmacological interventions [9]. Bearing in mind the negative impact that cognitive adverse events (e.g., impaired memory, attention, or executive function) can have on the lives of patients with epilepsy—negative effects on school or work performance, everyday life, and HRQoL overall—it is of paramount importance to assess the impact of each intervention on patients’ cognitive functioning.

In the European Union, brivaracetam (BRV) is approved as adjunctive treatment of focal-onset (partial-onset) seizures (FOS) in patients ≥ 2 years of age [10]. In the United States, BRV is approved as monotherapy and adjunctive treatment of FOS in patients ≥ 1 month of age [11].

A 12-month, prospective, noninterventional, post-marketing study (EP0077) collected real-world information on clinical outcomes, as well as HRQoL outcomes and cognitive performance, in patients initiating adjunctive BRV treatment according to routine clinical practice and the European Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) in nine countries in Europe. The aim was to evaluate the change in patient-related outcomes following the initiation of adjunctive treatment with BRV. Effectiveness outcomes of the study are presented separately [12], and an interim analysis has been published [13]. The overall study results showed the effectiveness of adjunctive BRV in a population of patients with difficult-to-treat FOS [with or without focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures (FBTCS; secondary generalized seizures)] when used in clinical practice across European countries [12]. At 12 months, 57.7% of patients remained on BRV treatment, 13.8% of patients were seizure-free since baseline, and 60.4% of patients had experienced a ≥ 50% seizure reduction since baseline. BRV in addition to the existing treatment regimen was well tolerated.

This paper focuses on summarizing patient outcomes for HRQoL and cognitive performance.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

EP0077 (BASE: Brivaracetam And Seizure reduction in Epilepsy; NCT02687711) was a prospective, noninterventional, post-marketing study initiated at 48 specialized sites (43 of which enrolled patients) across nine European countries (Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and United Kingdom). The observational period was 12 months.

Patients ≥ 16 years of age with a clinical diagnosis of epilepsy with FOS, with or without FBTCS, were eligible if they had not been treated with BRV before study entry and met the criteria for adjunctive treatment with BRV according to the SmPC in Europe. When the study started, BRV was approved as adjunctive treatment of FOS, with or without FBTCS, in patients with epilepsy ≥ 16 years of age. The recommended dosage range was 50–200 mg/day. The treating physician’s decision to initiate BRV had to have been made independently of the patient’s participation in this study. Patients had to use an epilepsy/seizure diary. Further details of the study methodology are described in the primary paper [12].

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee (see Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee appendix in the Supplementary Material), per country-specific regulations. Written data consent was obtained from the patient, parent(s), or legal representative before study participation, in accordance with local regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

As reported in the primary paper [12], at baseline, the mean age of patients was 43.6 years, and 52.8% of patients were female [Safety Set (SS), in Table 1] [12]. The mean time since first epilepsy diagnosis was 22.7 years. The most common seizure type was focal impaired awareness (complex partial-onset seizures; 76.8%). During the 3-month retrospective baseline period, patients had a median of 3.7 (first quartile, third quartile: 1.0, 12.0) FOS per 28 days; for 32.4% of patients, at least one FBTCS at baseline was recorded. Patients had a mean of 7.3 lifetime antiseizure medications (ASMs; the sum of the ASMs that were discontinued before study entry and those that were being used concomitantly at study entry); 77.9% were taking at least two concomitant ASMs at study entry (ASMs being taken on the same day as the first BRV administration); 59.2% were treated with levetiracetam before study entry. Overall, baseline characteristics for the Modified Full Analysis Set (mFAS) were similar to those for the SS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and epilepsy characteristics (SS and mFAS) [12]

| SSa (N = 544) | mFAS (N = 310) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 43.6 (14.1) | 44.9 (14.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 287 (52.8) | 165 (53.2) |

| Time since first diagnosis, mean (SD), years | 22.7 (15.0)b | 22.7 (15.5)c |

| Age at time of first diagnosis, mean (SD), years | 20.9 (17.3)b | 22.2 (18.0)c |

| Percentage of life with epilepsy, mean (SD), % | 53.5 (31.2)b | 51.8 (31.6)c |

| Seizure profile,d n (%) | ||

| Focal-onset seizures (partial-onset seizures) | 542 (99.6) | 309 (99.7) |

| Focal aware seizures (simple partial-onset seizures) | 225 (41.4) | 114 (36.8) |

| Focal impaired awareness seizures (complex partial-onset seizures) | 418 (76.8) | 230 (74.2) |

| Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures (partial-onset seizures evolving to secondarily generalized) | 362 (66.5) | 215 (69.4) |

| Baseline seizure frequency | ||

| Any baseline focal-onset seizures, n (%) | 451 (90.2)e | 252 (88.7)f |

| Any baseline focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, n (%) | 162 (32.4)e | 97 (34.0)g |

| 28-day focal-onset seizure frequencyh | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.7 (1.0, 12.0)e | 2.7 (0.7, 7.0)f |

| Mean (SD) | 15.0 (39.0)e | 9.8 (23.1)f |

| 28-day focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizure frequencyh | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.3)e | 0.0 (0.0, 0.7)g |

| Mean (SD) | 1.2 (8.4)e | 0.8 (2.2)g |

| VNS use at study entry, n (%) | 57 (10.7)i | 23 (7.7)j |

| Historical LEV use, n (%) | 322 (59.2) | 169 (54.5) |

| LEV use at study entry, n (%) | 148 (27.2) | 89 (28.7) |

| Discontinued LEV use post study entry, n (%)k | 127 (85.8) | 73 (82.0) |

| Number of ASMs at study entry,l mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.0) |

| 0, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 0 |

| 1, n (%) | 117 (21.5) | 70 (22.6) |

| 2, n (%) | 198 (36.4) | 131 (42.3) |

| 3, n (%) | 145 (26.7) | 74 (23.9) |

| > 3, n (%) | 81 (14.9) | 35 (11.3) |

| Number of lifetime ASMs,m mean (SD) | 7.3 (4.6) | 6.5 (4.0) |

| 0–3, n (%) | 127 (23.3) | 82 (26.5) |

| 4–6, n (%) | 141 (25.9) | 94 (30.3) |

| ≥ 7, n (%) | 276 (50.7) | 134 (43.2) |

ASM antiseizure medication, BRV brivaracetam, LEV levetiracetam, mFAS Modified Full Analysis Set, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, SD standard deviation, SS Safety Set, VNS vagus nerve stimulation

aThe Full Analysis Set included 541 of the 544 patients included in the SS. Hence, the baseline characteristics presented here are representative of both analysis sets

bn = 537

cn = 308

dSeizure profile includes all seizure types experienced in the patient’s life so far; seizure types are listed per the International League Against Epilepsy 2017 classification [48], with the 1981 classification [49] in parentheses; a patient may have had multiple seizure classifications

en = 500

fn = 284

gn = 285

h28-day adjusted baseline seizure frequency was calculated as the number of seizures recorded during the 3 months before first BRV administration divided by 3

iThe percentage of patients with or without VNS use at study entry was based on a total of 532 patients reporting data

jThe percentage of patients with or without VNS use at study entry was based on a total of 298 patients reporting data

kThe percentage was based on the number of patients with LEV use at study entry = “Yes”

lASMs at study entry were defined as those being taken on the same day as the first BRV administration, including VNS and LEV use if applicable

mLifetime ASMs were the sum of historical ASMs (those discontinued before the date of the first BRV administration) and the ASMs at study entry (including VNS and LEV counted only once)

Outcomes

HRQoL [Patient Weighted Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-Form 31 (QOLIE-31-P)] [14], change in overall condition [Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC), Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC)], and cognitive functioning [attention and executive functions (EpiTrack®)] [15] questionnaires were voluntarily completed by patients and physicians, provided these questionnaires were part of standard clinical practice at the participating sites.

The 31-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31) is a questionnaire developed to evaluate HRQoL in patients with epilepsy [16]. QOLIE-31 includes seven subscales covering general and epilepsy-specific domains and gives a composite score from 0 to 100 points, with a higher score reflecting higher self-reported HRQoL. The QOLIE-31-P is an adaptation of the QOLIE-31, with an extra item added to each subscale asking the patient to grade his or her overall “distress” related to each subscale topic and an item asking about the relative importance of each subscale topic [14]. Permission to use QOLIE-31-P in our study was obtained. The QOLIE-31-P outcomes presented in this paper include clinically meaningful changes from baseline to 6 and 12 months in total and subscale scores (seizure worry, overall quality of life, emotional well-being, energy/fatigue, cognitive functioning, medication effects, and social functioning).

The Clinical Global Impression scales were initially developed for a risk–benefit estimation within the treatment of patients with mental illnesses [17]. The four global scales (severity of illness, change in severity from baseline, therapeutic efficacy, and tolerability of treatment) are used to measure treatment outcome in different kinds of pharmacological studies. The change in severity scale (CGIC) was used in this study to evaluate the treating physician’s impression of changes in overall condition relative to baseline condition. The PGIC is a rating scale in which the patient evaluates their perceived changes in overall condition over time [18], and was completed during an interview between the patient and the treating physician or designee. Both scales range from 1 point (very much improved) to 7 points (very much worse). CGIC and PGIC outcomes at 6 and 12 months are presented in this paper.

EpiTrack® is a screening tool designed to detect and track cognitive side effects of ASMs and adverse effects of seizures in patients with epilepsy [15]. This 15-min tool comprises six simple subtests requiring attention, cognitive tracking, and working memory (interference, connecting numbers, connecting numbers and letters, maze test, verbal fluency, and inverted digit span; scored on a 7-point scale, with 1 point indicating the impaired end of the performance range) and has been validated for use with patients aged 16–87 years. EpiTrack® has been demonstrated to be sensitive to the effects of seizures, polytherapy, and specific drugs on cognition in patients with epilepsy [15], and its usefulness has been shown in two noninterventional studies [19, 20]. The adult version of EpiTrack® was used in this study. EpiTrack® outcomes presented herein include subtest scores, the age-corrected EpiTrack® score, and performance category—change from baseline to 6 and 12 months.

Post Hoc Analysis

A post hoc analysis was performed on patient subgroups based on the number of lifetime ASMs (0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7), defined as the sum of the ASMs discontinued before study entry and concomitant at study entry. Analyzed outcomes included change in QOLIE-31-P from baseline to 6 and 12 months, CGIC at 6 and 12 months, and PGIC at 6 and 12 months. EpiTrack® was not considered due to the small numbers of patients with available completed data.

Statistical Analyses

Available data were summarized using descriptive statistics, and there were no inferential analyses, nor were missing data imputed. Because the patient-related instruments were completed only where they were part of the standard clinical practice of the participating sites and were voluntary, the data were not available for all patients.

The SS comprised all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of BRV. The Full Analysis Set (FAS) comprised all patients in the SS who did not receive BRV before entering the study. The mFAS included all patients in the FAS who were treated according to the approved SmPC, representing the recommended use of BRV as per the European SmPC. Outcomes were analyzed using the FAS and mFAS.

QOLIE-31-P subscale and total scores were calculated according to the scoring algorithm defined in the scoring manual, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 points and higher scores indicating better HRQoL. Clinically meaningful changes from baseline in QOLIE-31-P total and subscale scores were defined according to Borghs et al. [21] (improvement, no change, or worsening, based on the minimally important change thresholds) and evaluated after 6 and 12 months of treatment.

CGIC and PGIC data were summarized as the proportions of patients with an improvement (very much improved, much improved, or minimally improved), no change, and a worsening (minimally worse, much worse, or very much worse) in overall condition after 6 and 12 months of treatment.

Analysis of EpiTrack® results followed the EpiTrack® test protocol rules [15, 19, 20, 22–26]. The EpiTrack® score in points was calculated by entering the subtest raw scores into a conversion table to obtain a point score for each subtest, calculating a total score out of the single point scores, and applying an age correction. EpiTrack® results were categorized into four cognitive performance categories based on the EpiTrack® score (excellent: ≥ 39 points; average: 32–38 points; mildly impaired: 29–31 points; significantly impaired: ≤ 28 points). Significant change in EpiTrack® score from baseline to 6 and 12 months was evaluated as follows: improvement was defined as an increase in score of ≥ 4 points; no change was defined as a change in score of − 2 to 3 points inclusive; and worsening was defined as a change in score of at least − 3 points [15, 19, 20, 22–26].

Analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Disposition

Of the 548 patients who were enrolled, 544 received at least one dose of adjunctive BRV during the study period and were included in the SS (number of patients in each country: Denmark, 37; Germany, 100; Hungary, 82; Ireland, 17; Italy, 21; Netherlands, 31; Norway, 34; Spain, 43; United Kingdom, 179) [12]. Of these 544 patients, 541 were included in the FAS (number of patients in each country: Denmark, 37; Germany, 100; Hungary, 80; Ireland, 17; Italy, 21; Netherlands, 31; Norway, 34; Spain, 42; United Kingdom, 179), and 310 who received adjunctive BRV as per the European SmPC throughout the study were included in the mFAS.

HRQoL and Cognitive Performance Outcomes: Overall Study Population

Among patients available in the FAS, 84 (15.5%) to 183 (33.8%) and 61 (11.3%) to 148 (27.4%) had data for QOLIE-31-P total and subscale scores, CGIC, PGIC, and EpiTrack® score and subtest scores at 6 and 12 months, respectively (Fig. S1). Among patients available in the mFAS, the number who had data for these outcomes at 6 and 12 months was 46 (14.8%) to 105 (33.9%) and 42 (13.5%) to 93 (30.0%), respectively.

QOLIE-31-P

The mean QOLIE-31-P total score at baseline for patients with data in the FAS was 51.5 points (n = 228), with mean changes of 5.0 and 6.2 points at 6 (n = 129) and 12 (n = 103) months, respectively, indicating improvements in HRQoL in patients who provided data at these visits (Table 2). From baseline to 6 and 12 months, 43.4% and 46.6% of patients, respectively, reported a meaningful improvement in QOLIE-31-P total score, and 17.1% and 15.5% of patients reported worsening (FAS; Fig. 1a). The subdomains with ≥ 50% of patients reporting a meaningful improvement at either time point were seizure worry [proportion of patients at 6 and 12 months, respectively: 44.0% and 50.0% (n = 134, n = 108)], cognitive functioning [53.0% and 50.0% (n = 134, n = 108)], medication effects [54.1% and 52.3% (n = 133, n = 107)], and social functioning [56.9% and 58.1% (n = 130, n = 105)] (FAS; Fig. 1a).

Table 2.

Observed results and changes from baseline in QOLIE-31-P total score (FAS and mFAS)

| FAS (N = 541) | mFAS (N = 310) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Observed result, mean (SD) | n | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | n | Observed result, mean (SD) | n | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | |

| Baseline | 228 | 51.5 (18.9) | – | – | 131 | 50.5 (18.9) | – | – |

| 6 months | 144 | 59.5 (17.3) | 129 | 5.0 (12.6) | 83 | 60.1 (17.6) | 74 | 7.0 (12.7) |

| 12 months | 118 | 61.9 (17.5) | 103 | 6.2 (13.7) | 79 | 60.0 (17.9) | 69 | 6.8 (14.7) |

FAS Full Analysis Set, mFAS Modified Full Analysis Set, QOLIE-31-P Patient Weighted Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-Form 31, SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Clinically meaningfula changes in QOLIE-31-P scores from baseline to 6 and 12 months in the FAS (a) and mFAS (b). FAS Full Analysis Set, m month, mFAS Modified Full Analysis Set, QoL quality of life, QOLIE-31-P Patient Weighted Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-Form 31. aClinically meaningful thresholds were defined according to Borghs et al. [21]: total score 5.19, seizure worry 7.42, overall QoL 6.42, emotional well-being 4.76, energy/fatigue 5.25, cognitive functioning 5.34, medication effects 5.00, social functioning 3.95

Results for the mFAS were similar, including mean changes in QOLIE-31-P total score (Table 2) and meaningful changes in QOLIE-31-P scores (Fig. 1b) from baseline to 6 and 12 months.

CGIC

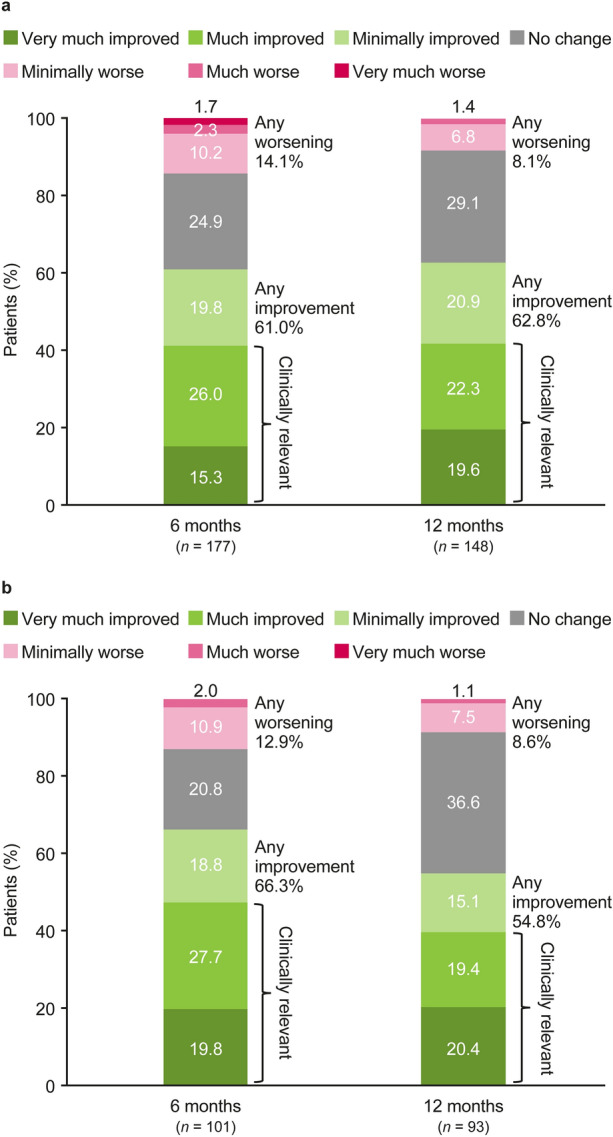

Based on the CGIC (physician’s assessment determined relative to the baseline condition), at 6 (n = 183) and 12 months (n = 142), most patients had an improvement in overall condition (61.2% and 69.0%, respectively): 13.1% and 21.8% were “very much improved,” and 24.0% and 24.6% were “much improved” (FAS) (Fig. 2a). A worsening in overall condition was reported for 13.1% and 3.5% of patients at 6 and 12 months, respectively (FAS). Overall, the CGIC results were similar in the mFAS population (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Clinical Global Impression of Change at 6 and 12 months in the FAS (a) and mFAS (b). FAS Full Analysis Set, mFAS Modified Full Analysis Set. “Clinically relevant” is as interpreted by participating physicians in the clinical routine

PGIC

Based on the PGIC, at 6 (n = 177) and 12 (n = 148) months, most patients reported that their overall condition had improved relative to their condition before study entry (61.0% and 62.8%, respectively): 15.3% and 19.6% reported being “very much improved,” and 26.0% and 22.3% reported being “much improved” (FAS) (Fig. 3a). A worsening in overall condition was reported by 14.1% and 8.1% of patients at 6 and 12 months, respectively (FAS). PGIC results for the mFAS population were generally similar to those observed in the FAS population (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Patient’s Global Impression of Change at 6 and 12 months in the FAS (a) and mFAS (b). FAS Full Analysis Set, mFAS Modified Full Analysis Set. “Clinically relevant” is as interpreted by participating physicians in the clinical routine

EpiTrack®

The mean EpiTrack® score at baseline for patients with data in the FAS was 27.7 points (n = 142), with mean changes of 1.2 and 1.7 points at 6 (n = 82) and 12 (n = 61) months, respectively, indicating that cognitive functioning was stable in patients with data at these visits (Table S1). The majority of patients showed no significant change in EpiTrack® score from baseline to 6 or 12 months [67.1% and 67.2%, respectively (n = 82, n = 61)] 22.0% and 23.0% of patients showed improvement and 11.0% and 9.8% showed worsening compared with baseline status (FAS; Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

EpiTrack® outcomes: significant changesa in EpiTrack® score from baseline to 6 and 12 months (a); EpiTrack® cognitive performance categoriesb at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months (b); EpiTrack® cognitive performance subtest scores (mean)c at baseline and 6 months (c) and at baseline and 12 months (d) (FAS). BL baseline, FAS Full Analysis Set. aImprovement was defined as an increase in score of ≥ 4 points; no change was defined as a change in score of − 2 to 3 points inclusive; worsening was defined as a change in score of at least − 3 points. bExcellent: ≥ 39 points; average: 32–38 points; mildly impaired: 29–31 points; significantly impaired: ≤ 28 points. Out-of-plausible-range individual point scores were set to missing before summarizing and deriving the data. cPresented are the point score categories (after raw scores were translated into points). Out-of-plausible-range individual point scores were set to missing before summarizing and deriving the data. Each of the EpiTrack® subtests was collected in 143–145 patients at baseline, 84–85 patients at 6 months, and 61 patients at 12 months

Based on the performance categories of EpiTrack® at baseline (n = 142; FAS), 14.8% of patients had mildly impaired cognitive performance and 49.3% had significantly impaired cognitive performance (Fig. 4b). At 6 (n = 84) and 12 (n = 61) months, lower proportions of patients had mildly impaired and significantly impaired cognitive performance compared with baseline (10.7% and 33.3%, respectively, at 6 months; 4.9% and 36.1%, respectively, at 12 months), indicating improvements in overall cognitive performance. At baseline, 2.8% of patients with data had excellent cognitive performance and 33.1% had average cognitive performance (FAS; Fig. 4b). At 6 months and 12 months, higher proportions of patients had excellent and average cognitive performance versus baseline (3.6% and 52.4%, respectively, at 6 months; 6.6% and 52.5%, respectively, at 12 months).

Patients in the mFAS showed similar results for mean change from baseline (Table S1) and significant change (Fig. S2a) in EpiTrack® score and for EpiTrack® cognitive performance categories (Fig. S2b).

Mean EpiTrack® subtest scores at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months are shown in Fig. 4c and d (FAS) and Figs. S2c and d (mFAS). Overall, mean changes from baseline in EpiTrack® subtest scores for the FAS were small [0.1–0.4 on scales of 1–7 points (6 months: n = 83, 12 months: n = 61)] indicating stability in the overall cognitive functioning.

Post Hoc Analysis: Subgroups Analyzed by Number of Lifetime ASMs

Baseline Characteristics

Of the 541 patients in the FAS, 127 (23.5%), 141 (26.1%), and 273 (50.5%) had 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs, respectively (Table S2). In patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs, the median number of FOS per 28 days was 1.3, 2.7, and 6.7; the mean time since first diagnosis was 11.9, 20.8, and 28.8 years; and the mean percentage of life with epilepsy was 29.6%, 50.4%, and 66.5%, respectively. Baseline characteristics were similar in the mFAS (Table S2).

HRQoL Outcomes

QOLIE-31-P

The mean QOLIE-31-P total score at baseline was similar in patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs [49.9 (standard deviation: 18.1) points, n = 53; 50.6 (20.1) points, n = 71; and 53.0 (18.5) points, n = 104, respectively; FAS]. In patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs, respectively, a clinically meaningful improvement from baseline in QOLIE-31-P total score was reported in 54.5%, 39.0%, and 40.0% of patients at 6 months; and in 60.0%, 39.5%, and 45.0% of patients at 12 months (FAS; Fig. S3a). Results for the mFAS were generally similar, except that the proportions of patients with ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs who had a meaningful improvement at 6 and 12 months were numerically higher versus the FAS (Fig. S3b).

CGIC

For most patients in all subgroups, improvement was reported in the CGIC at both 6 months [68.1%, 63.6%, and 55.6% of patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs, respectively (n = 47, n = 55, n = 81)] and 12 months [76.3%, 73.9%, and 60.3% of patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs, respectively (n = 38, n = 46, n = 58)] (FAS; Fig. S4a). Results for the mFAS were generally similar (Fig. S4b).

PGIC

Results of the PGIC showed similar outcomes to the CGIC [patients with 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs reporting any improvement: 70.5%, 65.4%, and 53.1%, respectively (n = 44, n = 52, n = 81) at 6 months; 75.7%, 63.3%, and 54.8%, respectively (n = 37, n = 49, n = 62)], at 12 months (FAS; Fig. S5a). Results for the mFAS were generally similar (Fig. S5b).

Discussion

It is increasingly recognized that seizure control is only one aspect of the comprehensive management of epilepsy: cognitive, physical, and psychological functioning factors all influence patients’ overall well-being and HRQoL, and require comprehensive evaluation [27, 28]. Therefore, the purpose of treating epilepsy is not necessarily seizure freedom only; rather, one of the desired treatment goals should be to obtain an improvement in patients’ HRQoL, considering their overall condition, characteristics, and the progress of disease.

EP0077 was a prospective, noninterventional study of adjunctive BRV treatment that enrolled a large cohort of patients across nine European countries. The prospective design was one of the strengths of this study, as it allowed some HRQoL and cognitive functioning instruments, if used in the clinical routine, to be integrated into the study and these important insights to be collected from both patients and physicians. A number of studies have evaluated the impact of ASMs on patients’ HRQoL [29–37] and cognition [20, 33, 36, 38–40]. However, EP0077 is one of the few studies with HRQoL and cognitive functioning data related to the initiation of adjunctive BRV therapy in a real-world setting, with a relatively large patient population and long-term follow-up of 12 months. Additionally, being noninterventional per design, this study had wider patient selection criteria compared with those from randomized controlled trials, giving more representativeness to the study population and therefore more generalizable findings for clinicians. A potential limitation of this multinational study is that the results may have been affected by heterogeneity from variation in clinical practice across participating countries. The interpretation of the study outcomes also needs to take into account the fact that the patient population had difficult-to-treat FOS, with a mean of 7.3 lifetime ASMs and 2.4 ASMs at study entry (SS). In addition, it is possible that the outcomes were affected by changes in concomitant ASMs that the patients were taking. A recent pooled analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials showed that BRV was efficacious and generally well tolerated in patients with FOS, regardless of the patients’ concomitant ASMs, including first-, second-, and third-generation ASMs and both sodium channel blockers and non-sodium channel blockers (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, valproate, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, phenytoin, lacosamide, clobazam, or phenobarbital) [41]. However, it is unclear whether concomitant ASMs affect HRQoL and cognitive performance outcomes for BRV. Because the questionnaires included in this study were to be used only if they were part of standard clinical practice at a given site and were voluntary, data from these assessments were available for only a limited number of patients.

In this population of patients (≥ 16 years of age) with FOS, 43.4% of patients reported a clinically meaningful improvement in HRQoL (QOLIE-31-P total score) at 6 months, and this was sustained through 12 months (46.6%) after initiating adjunctive BRV treatment at baseline (FAS). The observed improvement in HRQoL may have resulted from additional seizure control from adjunctive BRV, or the elimination of side effects of a previous ASM if side effects were the reason for switching to BRV. The proportion of patients reporting a meaningful improvement at 12 months was in line with those reported by Toledo et al. [35] (42.4%) for an open-label, flexible-dose trial with adjunctive BRV, and O'Brien et al. [34] (49%) for a phase 3, open-label, long-term follow-up trial, both of which enrolled patients ≥ 16 years of age with focal- or generalized-onset seizures. However, the proportions of patients reporting a meaningful improvement in the QOLIE-31-P subdomains of seizure worry, cognitive functioning, medication effects, and social functioning at 12 months in the current study were numerically higher than those reported by Toledo et al. [35] [50.0–58.1% (FAS) vs. 39.6–54.5%]. These differences may be explained by the fact that the current study was noninterventional, whereas the study reported by Toledo et al. [35] was an open-label follow-up trial with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria in the preceding trials, and by differences in baseline characteristics of the two study populations.

The CGIC and PGIC were used to assess the patients’ overall condition during adjunctive BRV treatment relative to their baseline condition, as determined by the treating physician and self-reported by patients. Based on the CGIC, an improvement was observed for most patients at both 6 and 12 months (61.2% and 69.0%, respectively; FAS). The results of the PGIC at 6 and 12 months (61.0% and 62.8%, respectively) were similar to or slightly numerically lower than those reported by the treating physicians, indicating that physicians and patients had a generally similar impression of changes in overall condition during the observational period, following initiation of the adjunctive BRV treatment (FAS). To our knowledge, only one other prospective study has reported Global Impression of Change data for BRV, and the results were from an interim analysis [42, 43]. In that post-marketing, noninterventional study of patients aged ≥ 18 years with FOS in Europe and Canada, 51.2% of patients improved per CGIC and 55.0% improved per PGIC at 12 months after initiating adjunctive BRV in earlier treatment lines. These percentages are lower than those observed in the current study, which may be related to differences in patient selection criteria or study location.

To our knowledge, this is the only prospective study with long-term EpiTrack® outcomes for BRV. EpiTrack® cognitive performance categories indicated that the study population comprised mostly patients with mildly or significantly impaired cognitive performance (FAS). In line with the result that 50.0% of patients reported a clinically meaningful improvement in the QOLIE-31-P cognitive functioning subdomain after 12 months of adjunctive BRV therapy, the EpiTrack® score showed that 23.0% of patients experienced a significant improvement in cognitive functioning and 67.2% remained stable during the observational period (FAS). Furthermore, compared with baseline, at 6 months, lower proportions of patients had mildly or significantly impaired cognitive performance, and higher proportions had excellent or average cognitive performance (FAS). These changes were also observed at 12 months compared with baseline, indicating a sustained effect. The EpiTrack® results seen in this study were generally consistent with those of a retrospective study in patients with epilepsy (n = 43) in a naturalistic clinical setting, in which the patients underwent a neuropsychological screening including EpiTrack® before adjunctive treatment with BRV and a follow-up evaluation after either 5 days or 25 weeks [36]. It is known that cognition is negatively affected by increasing ASM load, and that executive function decreases with each additional ASM in polytherapy [44]. Therefore, our observation that BRV addition did not have negative effects on cognitive performance is encouraging.

Post Hoc Subgroup Analysis by Number of Lifetime ASMs

The post hoc subgroup analysis showed that patients with fewer lifetime ASMs had a greater improvement in HRQoL at both 6 and 12 months (FAS). However, patients with ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs could also improve in HRQoL with adjunctive BRV treatment: 40.0% of these patients showed a clinically meaningful improvement in QOLIE-31-P total score at 6 months, and the proportion was slightly higher at 12 months (45.0%; FAS). These results differ from those of a post hoc analysis of phase 3 trials of adjunctive BRV in patients 16–80 years of age with focal seizures, which found no clear pattern in the proportion of patients with a meaningful improvement in QOLIE-31-P total score at 12 months by the number of lifetime ASMs [37]. The discrepancy may be linked to the subgroups analyzed (0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs in this study vs. 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs in Brandt et al. [37]) or differences in study design. In the current study, most patients with ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs showed improvements in the CGIC and PGIC at both 6 and 12 months (FAS). Patients with fewer lifetime ASMs were previously shown to have a better efficacy response to BRV [37, 45, 46]. This may be a factor in the greater improvement in HRQoL seen in these patients. A limitation of the subgroup analysis is its post hoc nature; interpretation of the analysis is also limited by the low patient numbers in some subgroups with available data.

Conclusions

There are different treatment goals that might be important to patients with epilepsy. Besides clinical goals such as seizure freedom and seizure control, patient-relevant goals in improving overall quality of life should be better considered and implemented in the decision-making for a new therapeutic option [47]. In this European, real-world, prospective study in patients with difficult-to-treat FOS with or without FBTCS, cognitive functioning after initiating BRV remained stable for 12 months of adjunctive treatment in most patients, and nearly a quarter of patients experienced significant improvements (measured by the EpiTrack® instrument). Clinically meaningful improvements in HRQoL (QOLIE-31-P total score) were reported by 46.6% of patients at 12 months. Improvements in patients’ overall condition (CGIC and PGIC) were observed in 69.0% and 62.8% of patients, respectively, at 12 months. Patients with fewer lifetime ASMs, as expected, showed a greater improvement in HRQoL (QOLIE-31-P, CGIC, and PGIC), although patients with ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs could also benefit from BRV treatment; in this subgroup, more than half of the patients with CGIC or PGIC data showed improvement at 12 months.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers in addition to the participating physicians and their teams who contributed to the study.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Writing assistance was provided by Emily Chu, PhD (Evidence Scientific Solutions Ltd, Horsham, UK), and was funded by UCB. The authors acknowledge Jakob Christensen, MD, PhD (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark) and John Paul Leach, MD (formerly School of Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK) for contribution to an earlier draft of this manuscript. Publication management was provided by Vincent Laporte, PhD (UCB, Brussels, Belgium).

Author Contributions

Eduardo Rubio-Nazabal was responsible for investigation and writing—review and editing. Marian Majoie was responsible for investigation and writing—review and editing. Anne-Liv Schulz was responsible for methodology and writing—review and editing. Fiona Brock was responsible for methodology, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing. Iryna Leunikava was responsible for methodology and writing—review and editing. Dimitrios Bourikas was responsible for methodology and writing—review and editing. Bernhard J. Steinhoff was responsible for investigation and writing—review and editing.

Funding

This work and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were supported by UCB. UCB was involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in the decision to publish the manuscript. Several authors (Anne-Liv Schulz, Fiona Brock, Iryna Leunikava, and Dimitrios Bourikas) are employees of UCB.

Data Availability

Data from noninterventional studies are outside of UCB’s data sharing policy and are unavailable for sharing.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Eduardo Rubio-Nazabal has received honoraria from BIAL, Eisai, and UCB for speaking. Marian Majoie has received financial compensation through her institution for participating in contract research from Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Zogenix. Anne-Liv Schulz, Fiona Brock, Iryna Leunikava, and Dimitrios Bourikas are employees of UCB. Anne-Liv Schulz and Dimitrios Bourikas have received UCB stocks from their employment. Bernhard J. Steinhoff has received honoraria for consulting (from Angelini Pharma, Arvelle Therapeutics, B. Braun Melsungen, Desitin, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuraxpharm, and UCB), for serving on a scientific advisory board (from Arvelle Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Zogenix), and for speaking (from Arvelle Therapeutics, Desitin, Eisai, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Zogenix), and has received research support from Eisai, SK Life Science, and UCB.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee (see Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee appendix in the Supplementary Material), per country-specific regulations. Written data consent was obtained from the patient, parent(s), or legal representative before study participation, in accordance with local regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Part of this work was presented as posters at the 34th International Epilepsy Congress (August 28–September 1, 2021; virtual), the Canadian League Against Epilepsy 2021 Scientific Meeting (September 24–26, 2021; virtual), and the 14th European Epilepsy Congress (July 9–13, 2022; Geneva, Switzerland).

References

- 1.Saadi A, Patenaude B, Mateen FJ. Quality of life in epilepsy—31 inventory (QOLIE-31) scores: a global comparison. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;65:13–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalava M, Sillanpää M, Camfield C, Camfield P. Social adjustment and competence 35 years after onset of childhood epilepsy: a prospective controlled study. Epilepsia. 1997;38(6):708–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiebe S, Bellhouse DR, Fallahay C, Eliasziw M. Burden of epilepsy: the Ontario Health Survey. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26(4):263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner AK, Bungay KM, Kosinski M, Bromfield EB, Ehrenberg BL. The health status of adults with epilepsy compared with that of people without chronic conditions. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor RS, Sander JW, Taylor RJ, Baker GA. Predictors of health-related quality of life and costs in adults with epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2011;52(12):2168–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan P, Yu E, Leung H, Leon T, Mychaskiw MA. Association of subjective anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance with quality-of-life ratings in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guekht AB, Mitrokhina TV, Lebedeva AV, et al. Factors influencing on quality of life in people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2007;16(2):128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon CS, Jacoby A, Ali A, et al. Systematic review of frequency of felt and enacted stigma in epilepsy and determining factors and attitudes toward persons living with epilepsy—report from the International League Against Epilepsy Task Force on Stigma in Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2022;63(3):573–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmstaedter C, Sadat-Hossieny Z, Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Cognitive disorders in epilepsy II: clinical targets, indications and selection of test instruments. Seizure. 2020;83:223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UCB Pharma SA: Summary of product characteristics Briviact® (Europe). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/briviact-epar-product-information_en.pdf (2024). Accessed 9 July 2024.

- 11.UCB Inc.: BRIVIACT® (brivaracetam) prescribing information. https://www.briviact.com/briviact-PI.pdf (2023). Accessed 9 July 2024.

- 12.Steinhoff BJ, Christensen J, Doherty CP, et al. Effectiveness during 12-month adjunctive brivaracetam treatment in patients with focal-onset seizures in a real-life setting: a prospective, observational study in Europe. Neurol Ther. 2025. 10.1007/s40120-024-00697-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Steinhoff BJ, Christensen J, Doherty CP, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with focal seizures: second interim analysis of 6-month data from a prospective observational study in Europe. Epilepsy Res. 2020;165:106329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer JA, Van Hammée G, N132 Study Group. Maintenance of improvement in health-related quality of life during long-term treatment with levetiracetam. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(2):118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutz MT, Helmstaedter C. EpiTrack: tracking cognitive side effects of medication on attention and executive functions in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(4):708–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer JA, Perrine K, Devinsky O, et al. Development and cross-cultural translations of a 31-item quality of life in epilepsy inventory. Epilepsia. 1998;39(1):81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guy W, Bonato RR. Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery. 2nd ed. Chevy Chase: National Institute of Mental Health; 1970.

- 18.Hurst H, Bolton J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmstaedter C, Witt JA. The effects of levetiracetam on cognition: a non-interventional surveillance study. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(4):642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmstaedter C, Witt JA. Cognitive outcome of antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam versus carbamazepine monotherapy: a non-interventional surveillance trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;18(1–2):74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghs S, de la Loge C, Cramer JA. Defining minimally important change in QOLIE-31 scores: estimates from three placebo-controlled lacosamide trials in patients with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23(3):230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helmstaedter C, Witt JA. Chapter 28 - Clinical neuropsychology in epilepsy: theoretical and practical issues. In: Stefan H, Theodore WH, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology; 2012. vol. 107, p. 437–59. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52898-8.00036-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Witt JA, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Which drug-induced side effects would be tolerated in the prospect of seizure control? Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29(1):141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witt JA, Helmstaedter C. Monitoring the cognitive effects of antiepileptic pharmacotherapy–approaching the individual patient. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26(3):450–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Helmstaedter C, Witt JA. The longer-term cognitive effects of adjunctive antiepileptic treatment with lacosamide in comparison with lamotrigine and topiramate in a naturalistic outpatient setting. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26(2):182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helmstaedter C, Witt J. Modelling the cognitive effects of common antiepileptic drugs: a cross sectional head-to-head comparison using the EpiTrack. 10th European Congress on Epileptology. Epilepsia. 2012;53(S5):121.

- 27.Kugoh T. Quality of life in adult patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1996;37(Suppl 3):37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazil CW. Comprehensive care of the epilepsy patient–control, comorbidity, and cost. Epilepsia. 2004;45(Suppl 6):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moseley BD, Gupta S, Way N, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in adult patients diagnosed with epilepsy being treated with perampanel. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2022;13:39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elizebath R, Zhang E, Coe P, et al. Cenobamate treatment of focal-onset seizures: quality of life and outcome during up to eight years of treatment. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;116:107796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hixson J, Gidal B, Pikalov A, et al. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate as a first or later adjunctive therapy in patients with focal seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2021;171:106561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppola A, Zarabla A, Maialetti A, et al. Perampanel confirms to be effective and well-tolerated as an add-on treatment in patients with brain tumor-related epilepsy (PERADET Study). Front Neurol. 2020;11:592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Góngora M, Martínez-Domeño A, García C, Escartín A. Effect of levetiracetam on cognitive functions and quality of life: a one-year follow-up study. Epileptic Disord. 2008;10(4):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Brien TJ, Borghs S, He QJ, et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and quality of life outcomes with adjunctive brivaracetam treatment at individualized doses in patients with epilepsy: an up to 11-year, open-label, follow-up trial. Epilepsia. 2020;61(4):636–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toledo M, Brandt C, Quarato PP, et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and quality of life during adjunctive brivaracetam treatment in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy: an open-label follow-up trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witt JA, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Short-term and longer-term effects of brivaracetam on cognition and behavior in a naturalistic clinical setting—preliminary data. Seizure. 2018;62:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt C, Dimova S, Elmoufti S, et al. Retention, efficacy, tolerability, and quality of life during long-term adjunctive brivaracetam treatment by number of lifetime antiseizure medications: a post hoc analysis of phase 3 trials in adults with focal seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;138:108967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SA, Lee HW, Heo K, et al. Cognitive and behavioral effects of lamotrigine and carbamazepine monotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed or untreated partial epilepsy. Seizure. 2011;20(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levisohn PM, Mintz M, Hunter SJ, Yang H, Jones J. Neurocognitive effects of adjunctive levetiracetam in children with partial-onset seizures: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, noninferiority trial. Epilepsia. 2009;50(11):2377–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shehata GA, Bateh AE-aM, Hamed SA, Rageh TA, Elsorogy YB. Neuropsychological effects of antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine versus valproate) in adult males with epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:527–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moseley B, Bourikas D, Dimova S, Elmoufti S, Borghs S. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with focal-onset seizures on specific concomitant antiseizure medications: pooled analysis of double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Adv Ther. 2024;41(4):1746–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Knake S, de Curtis M, Kobayashi E, et al. Brivaracetam adjunctive therapy in earlier treatment lines in adults with focal-onset seizures in Europe and Canada: interim results of 12-month real-world data from BRITOBA (abstract 2.27). https://aesnet.org/abstractslisting/brivaracetam-adjunctive-therapy-in-earlier-treatment-lines-in-adults-with-focal-onset-seizures-in-europe-and-canada-interim-results-of-12-month-real-world-data-from-britoba (2023). Accessed 11 July 2024.

- 43.Knake S, De Curtis M, Kobayashi E, et al. Brivaracetam adjunctive therapy in earlier treatment lines in adults with focal-onset seizures in Europe and Canada: interim results of 12-month real-world data from BRITOBA (P8-1.008). Neurology. 2024;102(17).

- 44.Witt JA, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Adverse cognitive effects of antiepileptic pharmacotherapy: each additional drug matters. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(11):1954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, et al. Adjunctive brivaracetam in focal epilepsy: real-world evidence from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk STudy (BRIVAFIRST). CNS Drugs. 2021;35(12):1289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein P, McLachlan R, Foris K, et al. Effect of lifetime antiepileptic drug treatment history on efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with focal seizures: post-hoc analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsy Res. 2020;167:106369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker DA, Long L, Santilli N, Babrowicz J, Peck EY. Patient, caregiver, and healthcare professional perspectives on seizure control and treatment goals. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;117:107816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):522–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22(4):489–501. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from noninterventional studies are outside of UCB’s data sharing policy and are unavailable for sharing.