Abstract

Objectives

Mental health inequalities have increasingly become an important factor affecting social well-being. Existing researches have focused on the impact of digital inequalities on mental health, but there is lack of research exploring the impact of digital engagement on mental health inequalities.

Methods

Based on data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) wave 2020, this study analyzed the effects of digital engagement on adult mental health and mental health inequalities using multinomial OLS models and RIF models. Further, the mitigating effects of digital engagement on gender mental health inequalities and urban–rural mental health inequalities were calculated using RIF decomposition.

Results

Digital engagement positively predicts the mental health level of Chinese adults, and at the same time mitigates mental health inequalities among Chinese adults, including inequalities between genders and between urban and rural areas, and the mitigating effect on mental health inequalities is stronger between urban and rural areas. In addition, the mitigating effect of digital engagement on gender mental health inequalities diminished with increasing mental health levels; however, the mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequalities was stronger at low and high mental health levels.

Conclusions

Both gender mental health inequality and urban–rural mental health inequality are evident among Chinese adults. Digital engagement can alleviate overall mental health inequalities, including gender mental health inequalities and urban–rural mental health inequalities, while enhancing mental health. This provides new insights into how best to mitigate mental health inequalities in the digital era.

Keywords: Digital engagement, mental health inequalities, gender disparities, urban–rural disparities, resource substitution theory

Introduction

Reducing inequalities in health, especially in the field of mental health, is of high priority in numerous national health policies. Inequalities in mental health exist in access to care, use and outcomes of care, 1 which can be driven by income,2–4 education, 5 gender 6 and geographic area (urban or rural),7–9 especially in low- and middle-income countries. 10 In China, the lifetime prevalence of adult mental disorders is as high as 16.57%, and the prevalence of any of the depressive disorders is higher in women than in men, with a lifetime prevalence 1.44 times higher; the 12-month prevalence of any of the adult mental disorders (other than dementia) is 13.4% in rural areas, which is much higher than that of the urban population, which is 5.5%. 11 Indeed, the COVID-19 global pandemic had a severe impact on people's mental health, 12 but its effects were not evenly distributed across geographic locations and population groups, and even exacerbated existing mental health inequalities.13,14 Given the serious social and public health consequences, mitigating mental health disparities across populations remains a pressing public health issue.

Existing research reveals multiple predictors of mental health inequalities. First, under structured gender inequality, women were more likely to report experiencing depression, anxiety, and PTSD, among others,15–17 are almost twice as likely as men. 10 This is related to their work in health care, 18 exposure to the motherhood penalty in the labor market, 19 and a greater burden of family caregivers, 20 which contribute to women's to have higher levels of stress exposure than the male population. Several recent studies have confirmed that COVID-19 uniquely exacerbates the stressors and mental health risks experienced by women.9,21 In addition, a number of cross-sectional studies have suggested that China's unique urban–rural household registration system is an important environmental variable influencing mental health inequalities, particularly among older Chinese and rural female populations22–24. Urban Hukou holders generally enjoy higher levels of medical security, with broader coverage and higher reimbursement rates from medical insurance, resulting in a higher utilization rate of medical services. 25 It is evident that the uneven distribution of medical resources between urban and rural areas exacerbates healthcare inequality among urban and rural residents. 26 It is clear that the unequal and inadequate allocation of urban health resources under the household registration system is the main reason for the gap between the supply and demand of urban and rural mental health services. On one hand, the majority of hospitals and specialized medical personnel are concentrated in provincial capitals and economically prosperous eastern regions. On the other hand, primary healthcare facilities exhibit a deficiency in mental health service capabilities, with the majority of staff being part-time employees. 27 A study reveals that in 2018, the number of physicians per 10,000 people in rural China was 18, which is only 45% of that in urban areas. 28 Collectively, these factors have resulted in an exceedingly low treatment rate for mental disorders in rural areas, with the vast majority of affected individuals not receiving adequate care.

With the advancement of the digital wave, the impact of digital engagement on the mental health aspects of adults has been gradually noticed. Drawing from social support theory, some studies have suggested that extensive digital engagement can provide users with emotional and informational peer support29,30 and positively affect subjective well-being and life satisfaction.31,32 In addition, Internet use is not tied to the household registration system and has a high degree of generalizability relative to health and education resources, which vary widely between urban and rural areas. Taking the Chinese scenario as an example, as of December 2023, the internet penetration rate in urban areas of China is 83.3%, while in rural areas it stands at 66.5%, lagging behind urban areas by merely 16.8 percentage points. The gender ratio among internet users is 51.2:48.8, which is essentially in line with the overall population's gender ratio, indicating a gender balance in internet usage. 33 In rural areas with limited mental health resources, digital engagement has been recognized as having great potential to close the gap between mental health supply and demand.34,35 In fact, during the pandemic, mobile apps reduced stigmatizing attitudes and social distance associated with mental disorders by providing remote assessment, support, and intervention36–38.

There is no consensus on the mental health effects of digital engagement, but three main hypotheses exist. The first is known as the resource substitution theory. 39 It suggests that the positive effects of digital engagement on mental health are stronger in disadvantaged groups. When resources are substitutable for each other, having one resource makes up for the damage that may be caused by the absence of other resources. Therefore, the mental health effects of digital engagement are greater in disadvantaged groups than they are in advantaged groups. This means that having a particular resource (e.g. digital engagement) benefits individuals with fewer alternative resources (e.g. women living in rural areas) more. For example, use of electronic devices, support for family members’ use of the Internet, and their use of it for communication, entertainment, or as a tool are associated with fewer depressive symptoms, a finding that is even more pronounced among rural older adults. 40 In contrast, the resource multiplication theory 39 suggests that the same resources available to an advantaged group can lead to a higher return on health. For example, family strengths increase educational gains in self-rated health for men. 41 This is because dominant groups hold multiple resources that interact to create a stacking effect, amplifying the effect of one resource to perpetuate and expand their dominance. The third is the social dis-placement hypothesis, which states that digital engagement squeezes out users’ more valuable interaction time with family and friends, thus negatively impacting mental health. 42 For example, high Internet use intensity leads to deterioration in social behaviors and increases the likelihood of emotional problems, thus amplifying the negative impact of broadband Internet access on mental health. 43

Much of the existing research has explored the relationship between digital engagement and mental health. However, the association between digital engagement and mental health inequalities, and whether it increases or decreases mental health inequalities, including its impact on gender health inequalities and urban–rural health inequalities, remains under-recognized. With this in mind, this study focuses on whether digital engagement predicts mental health levels and mental health inequalities, as well as identifying whether digital engagement has a buffering or amplifying effect on mental health inequalities driven by gender and urban–rural factors.

Materials and methods

Data and participants

Based on cross-sectional data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2020 wave, this study adopts a quantitative analysis method, aiming to explore the impact of digital engagement on mental health inequalities among adults. It focuses on how digital engagement affects mental health inequalities between rural and urban areas and genders, and analyzes the role of digital engagement in mitigating or exacerbating mental health inequalities. CFPS 2020 wave data collection began in early July 2020 and ended in late December 2020. Covering 25 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions (a first-level administrative region under the national level, similar to the states in the United States) in mainland China, the target sample size is 16,000 households, and the survey respondents include all family members in the sample households, which is representative of the whole country, and thus can effectively reflect the mental health status of groups from different regions and backgrounds.

Since the measurements of digital engagement in this study were only measured in the CFPS 2020 wave dataset, this study chose to use the CFPS 2020 wave cross-sectional data for analysis (individual sample level). This study included a sample of all adults aged 20 and over (21,890) from the CFPS 2020 wave dataset. Based on this, invalid data samples were excluded from the core measures of numerical reference and mental health, resulting in the retention of 21,353 samples. Special note that invalid samples in this context refer to the following: respondent could not judge the question item; raw data were missing; the question item was not applicable; refused to answer; respondent's response to the question item was don’t know; and the situation of being interviewed did not apply to the respondent. The final sample of adults included in the analysis consisted of 10,713 (50.17%) males and 10,640 (49.83%) females; 10,448 (48.93%) rural and 10,905 (51.07%) urban.

Measures

Mental health

Among the available studies, studies by Yang et al. 44 and Yang et al. 45 used depressive symptoms measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to measure mental health; studies by Zhang et al., 46 Zu et al., 47 and Cao et al. 48 measured mental health in terms of both depressive symptoms and subjective well-being. Based on this, this study measured mental health in terms of both depressive symptoms and subjective well-being. Depressive symptoms were measured using a simplified Chinese CES-D8 scale, which measured how often a certain feeling or behavior occurred in the past week for the respondents, with the following specific items: (1) I feel depressed, (2) I find it hard to do anything, (3) I don’t sleep well, (4) I feel happy, (5) I feel lonely, (6) I am happy with my life, (7) I feel sad and upset, (8) I feel unable to go on with my life. The options were coded sequentially from 1 to 4 based on frequency of use, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.784. Subjective well-being was measured using a single question item that directly asked the respondent, “How happy do you think you are,” with a numerical value ranging from 0 to 10. Finally, using principal component analysis (PCA), a mental well-being score was calculated for the sample (KMO = 0.822; Bartlett sphericity test, p < 0.001; Cumulative = 52.67%), with higher scores indicating higher levels of mental health. It is important to note that the “mental health” indicator extracted by PCA is a synthetic indicator, a linear combination of depressive symptoms and subjective well-being, and it is more important to focus on the relative differences between groups. Negative values are simply a reflection of the scale and direction of the PCA component. It is a continuum from “mental unhealth” to “mental health” and a negative mean may simply mean that the average mental health of the sample is lower than the average of the overall sample.

Digital engagement

Referring to the research and coding method of Wang et al., 49 the study was conducted in terms of “accessing the Internet on computers”, “accessing the Internet on mobile devices”, “using WeChat “, “posting on social media”, “playing online games”, “shopping online”, “watching short videos”, and “online shopping” eight aspects of the use of digital use behavior to measure the digital engagement of the sample, never use coded as 0, other use coded as 1, and then aggregated and summed to get a score in the range of 0 to 8, the larger the value indicates a higher degree of digital engagement.

Control variables

For this research, control variables were selected in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, economic situation, health situation, and residential characteristics. Socio-demographic characteristics include age (continuous variable), gender (male, female), marriage (married, others) and years of education (continuous variable). Economic status included insurance (none, at least one) and annual personal income (continuous variable, units are 100,000 RMB). Health includes self-reported BMI and self-rated health status. Residence characteristics included Residence (Rural, Urban) and Residence area (northeast China, western China, central China, and eastern China).

Statistical analysis

In this research, descriptive statistics were first analyzed for the whole sample, male and female subsamples, and urban and rural subsamples using Stata17 (Table 1). Then, the effect of digital engagement on mental health was tested with the help of multinomial OLS model (Table 2), along with male and female subsamples, urban and rural subsamples.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of all variables (N = 21,353).

| Variable | Type of statistics | Total sample (n = 21,353) | Female sample (n = 10,640) | Male sample (n = 10,713) | Rural sample (n = 10,448) | Urban sample (n = 10,905) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | Mean (SD) | 0.00 (0.38) | −0.03 (0.39) | 0.03 (0.37) | −0.04 (0.40) | 0.03 (0.36) |

| Digital engagement | Mean (SD) | 2.79 (2.36) | 2.71 (2.35) | 2.87 (2.37) | 2.31 (2.28) | 3.25 (2.34) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | n (%) | 10,640 (49.83%) | 10,640 (100.00%) | 5089 (48.71%) | 5551 (50.90%) | |

| Male | n (%) | 10,713 (50.17%) | 10,713 (100.00%) | 5359 (51.29%) | 5354 (49.10%) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 46.60 (15.69) | 46.31 (15.67) | 46.90 (15.70) | 47.15 (15.62) | 46.08 (15.74) |

| Marriage status | ||||||

| Married | n (%) | 18,751 (87.81%) | 9627 (90.48%) | 9124 (85.17%) | 9218 (88.23%) | 9533 (87.42%) |

| Others | n (%) | 2602 (12.19%) | 1013 (9.52%) | 1589 (14.83%) | 1230 (11.77%) | 1372 (12.58%) |

| Years of education | Mean (SD) | 5.11 (6.15) | 5.14 (6.18) | 5.09 (6.12) | 4.23 (5.50) | 5.96 (6.61) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | n (%) | 10,448 (48.93%) | 5089 (47.83%) | 5359 (50.02%) | 10,448 (100.00%) | |

| Urban | n (%) | 10,905 (51.07%) | 5551 (52.17%) | 5354 (49.98%) | 10,905 (100.00%) | |

| Insurance | ||||||

| None | n (%) | 2003 (9.38%) | 1051 (9.88%) | 952 (8.89%) | 935 (8.95%) | 1068 (9.79%) |

| At least one | n (%) | 19,350 (90.62%) | 9589 (90.12%) | 9761 (91.11%) | 9513 (91.05%) | 9837 (90.21%) |

| Annual personal income (100,000 RMB) | Mean (SD) | 0.22 (0.39) | 0.14 (0.29) | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.15 (0.30) | 0.28 (0.45) |

| Self-assessed health status | Mean (SD) | 3.07 (1.19) | 2.96 (1.20) | 3.17 (1.18) | 3.06 (1.25) | 3.07 (1.13) |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 23.27 (3.46) | 22.90 (3.48) | 23.64 (3.40) | 23.11 (3.49) | 23.42 (3.43) |

| Residence area | ||||||

| Northeast China | n (%) | 2780 (13.02%) | 1469 (13.81%) | 1311 (12.24%) | 1198 (11.47%) | 1582 (14.51%) |

| Western China | n (%) | 6306 (29.53%) | 3062 (28.78%) | 3244 (30.28%) | 3817 (36.53%) | 2489 (22.82%) |

| Central China | n (%) | 5133 (24.04%) | 2607 (24.50%) | 2526 (23.58%) | 2602 (24.90%) | 2531 (23.21%) |

| Eastern China | n (%) | 7134 (33.41%) | 3502 (32.91%) | 3632 (33.90%) | 2831 (27.10%) | 4303 (39.46%) |

Table 2.

Regression results of digital engagement affect mental health.

| Variables | Full sample (M1) | By gender | By residence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (M2) | Male (M3) | Rural(M4) | Urban(M5) | ||

| Digital engagement | 0.011*** | 0.012*** | 0.009*** | 0.014*** | 0.008*** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Gender (ref: female) | 0.037*** | 0.043*** | 0.031*** | ||

| (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.006) | |||

| Age | 0.004*** | 0.003*** | 0.004*** | 0.003*** | 0.005*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Marriage status (ref: married) | −0.028** | 0.026* | −0.055*** | −0.033* | −0.026* |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

| Years of education | 0.004*** | 0.005*** | 0.003*** | 0.005*** | 0.005*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Residence (ref: rural) | 0.047*** | 0.049*** | 0.045*** | ||

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.007) | |||

| Insurance (ref: none) | 0.066*** | 0.065*** | 0.066*** | 0.087*** | 0.045*** |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.012) | |

| Annual personal income | 0.006 | −0.001 | 0.013 | −0.010 | 0.019** |

| (0.007) | (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.017) | (0.007) | |

| Self-assessed health status | 0.099*** | 0.104*** | 0.094*** | 0.102*** | 0.096*** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| BMI | 0.004*** | 0.005*** | 0.005*** | 0.003* | 0.005*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Residence area (ref: western China) | |||||

| Northeast China | 0.046*** | 0.044*** | 0.046*** | 0.053*** | 0.037** |

| (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.013) | |

| Central China | 0.044*** | 0.033** | 0.053*** | 0.058*** | 0.029** |

| (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Eastern China | 0.072*** | 0.063*** | 0.079*** | 0.075*** | 0.066*** |

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.010) | |

| Constant | −0.770*** | −0.787*** | −0.742*** | −0.738*** | −0.754*** |

| (0.028) | (0.039) | (0.040) | (0.042) | (0.039) | |

| Observations | 21,353 | 10,640 | 10,713 | 10,448 | 10,905 |

| R-Squared | 0.122 | 0.125 | 0.113 | 0.126 | 0.107 |

| F | 184.8*** | 107.0*** | 99.41*** | 102.6*** | 93.47*** |

Note: Cluster-robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

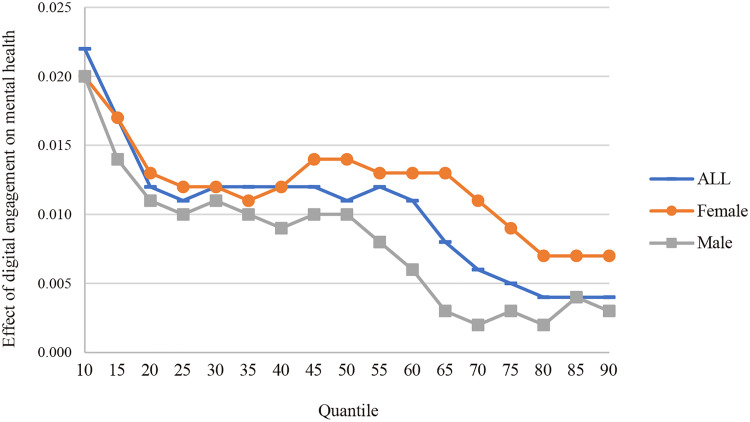

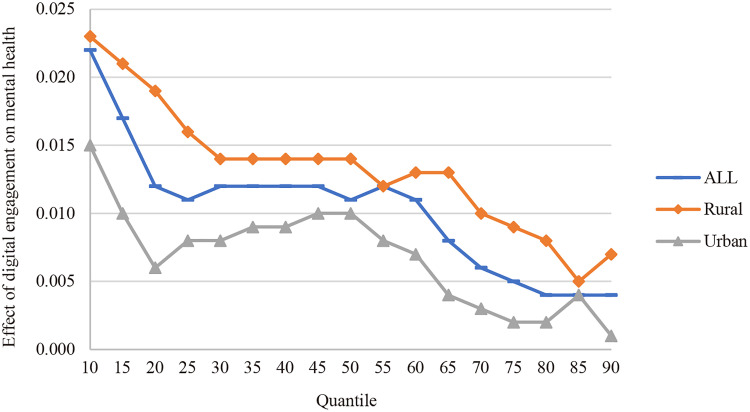

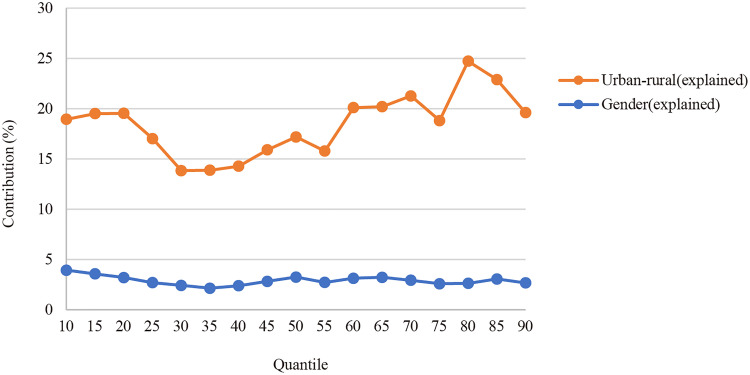

After empirically verifying the relationship between digital engagement on mental health, the RIF (recentered influence function) model is used to analyze the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequality. It is important to note that the RIF method is used to measure the effect of a small change in one place in the sample on a statistic. The RIF regression and RIF decomposition methods are mainly used in labor economics and economic policy evaluation research, and are used to explore the components of distributional inequality and intergenerational differences. For the principle and implementation method of RIF model, you can refer to the papers of Firpo et al. 50 and Rios-Avila. 51 In this research, the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities was examined using RIF regression models (inequalities are measured using the 90–10th percentile of the mental health index), as well as the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities between men and women and between urban and rural areas (Table 3). Then, RIF quantile regression was used to analyze the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities at different quartiles (Figures 1 and 2), including the overall sample, the urban–rural subsample and the gender subsample. Finally, the RIF decomposition method was used to calculate the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities between men and women (Table 4) and between urban and rural areas (Table 5), as well as the strength of the effect at different quartiles (Figure 3).

Table 3.

RIF regression results for digital engagement on mental health inequalities.

| Variables | Overall sample inequality (M6) | Gender inequality (M7) | Urban–rural inequality (M8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital engagement | −0.018*** | −0.015*** | −0.018*** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Gender (ref: female) | −0.016 | −0.002 | |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | ||

| Age | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Marriage status (ref: married) | 0.080*** | 0.090*** | 0.072*** |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| Years of education | −0.008*** | −0.007*** | −0.008*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Residence (ref: rural) | −0.043*** | −0.048*** | |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | ||

| Insurance (ref: none) | −0.100*** | −0.104*** | −0.081*** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | |

| Annual personal income | −0.033* | −0.040** | −0.054*** |

| (0.016) | (0.015) | (0.016) | |

| Self-assessed health status | −0.107*** | −0.101*** | −0.101*** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| BMI | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Residence area (ref: western China) | |||

| Northeast China | −0.020 | −0.017 | −0.020 |

| (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| Central China | −0.056** | −0.059*** | −0.056** |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| Eastern China | −0.072*** | −0.068*** | −0.069*** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| Constant | 1.537*** | 1.495*** | 1.512*** |

| (0.072) | (0.070) | (0.071) | |

| Observations | 21,353 | 21,353 | 21,353 |

| R-squared | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.033 |

| F | 46.80*** | 48.10*** | 47.52*** |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Effect of digital engagement on mental health at different quartiles by gender. Note: Confidence interval information for the regression coefficients is not shown due to limitations in visualization; the regression coefficients in this figure are all statistically significant at the 0.05 level of significance (p < 0.05), except at the 60th quantile, 65th quantile, 70th quantile, 75th quantile, 85th quantile, 90th quantile, for the male sample only.

Figure 2.

Effect of digital engagement on mental health at different quartiles by urban–rural. Note: Confidence interval information for the regression coefficients is not shown due to limitations in visualization; the regression coefficients in this figure are all statistically significant at the 0.05 level of significance (p < 0.05), except at the 20th quantile, 70th quantile, 75th quantile, 80th quantile, 90th quantile, for the urban sample only.

Table 4.

RIF decomposition results for gender mental health inequalities.

| Variables | 10th quantile | 50th quantile | 90th quantile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Contribution (%) | Coefficient | Contribution (%) | Coefficient | Contribution (%) | |

| Female | −0.539*** | 0.028*** | 0.408*** | |||

| Male | −0.458*** | 0.100*** | 0.451*** | |||

| Difference | −0.081*** | 100 | −0.072*** | 100 | −0.043*** | 100 |

| Explained | −0.038*** | 46.383 | −0.032*** | 45.209 | −0.015*** | 34.252 |

| Unexplained | −0.043*** | 53.617 | −0.039*** | 54.791 | −0.028*** | 65.748 |

| Digital engagement | −0.003** | 3.933 | −0.002*** | 3.257 | −0.001** | 2.672 |

| Age | −0.001 | 1.295 | −0.003** | 3.756 | −0.002** | 4.355 |

| Marriage status (ref: married) | 0.002 | −2.239 | −0.003** | 3.825 | −0.001 | 2.837 |

| Years of education | 0.000 | −0.440 | 0.000 | −0.274 | 0.000 | −0.167 |

| Residence (ref: rural) | 0.001** | −1.568 | 0.001** | −1.776 | 0.000* | −0.892 |

| Insurance (ref: none) | −0.001* | 1.339 | −0.001* | 0.934 | 0.000 | 0.246 |

| Annual personal income | −0.001 | 1.398 | 0.001 | −1.602 | 0.002 | −5.521 |

| Self-assessed health status | −0.033*** | 40.955 | −0.022*** | 31.219 | −0.011*** | 25.336 |

| BMI | −0.002 | 2.055 | −0.005*** | 6.356 | −0.003*** | 6.024 |

| Residence area (ref: western China) | ||||||

| Northeast China | 0.001 | −0.952 | 0.001 | −0.796 | 0.001* | −1.225 |

| Central China | 0.000 | −0.511 | 0.000 | −0.444 | 0.000 | −0.232 |

| Eastern China | −0.001 | 1.118 | −0.001 | 0.752 | 0.000 | 0.818 |

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

Table 5.

RIF decomposition results for urban–rural mental health inequalities.

| Variables | 10th quantile | 50th quantile | 90th quantile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Contribution (%) | Coefficient | Contribution (%) | Coefficient | Contribution (%) | |

| Rural | −0.556*** | 0.026*** | 0.419*** | |||

| Urban | −0.441*** | 0.100*** | 0.450*** | |||

| Difference | −0.116*** | 100 | −0.075*** | 100 | −0.031*** | 100 |

| Explained | −0.047*** | 40.357 | −0.026*** | 34.332 | −0.006** | 17.746 |

| Unexplained | −0.069*** | 59.643 | −0.049*** | 65.668 | −0.026*** | 82.254 |

| Digital engagement | −0.022*** | 18.951 | −0.013*** | 17.189 | −0.006** | 19.604 |

| Gender (ref: female) | 0.001 | −0.647 | 0.001** | −1.517 | 0.001** | −2.228 |

| Age | 0.001 | −0.933 | 0.004*** | −5.887 | 0.002*** | −7.794 |

| Marriage status (ref: married) | 0.001 | −0.742 | 0.000 | −0.105 | 0.000 | −0.742 |

| Years of education | −0.018*** | 15.232 | −0.008** | 10.816 | −0.001 | 1.916 |

| Insurance (ref: none) | 0.001 | −1.122 | 0.001 | −0.987 | 0.000 | −0.991 |

| Annual personal income | 0.000 | −0.411 | 0.001 | −1.099 | 0.004** | −11.718 |

| Self-assessed health status | −0.001 | 0.470 | 0.000 | 0.506 | 0.000 | 0.529 |

| BMI | 0.000 | 0.059 | −0.001** | 2.003 | −0.001** | 2.682 |

| Residence area (ref: western China) | ||||||

| Northeast China | −0.002 | 1.338 | −0.002*** | 2.815 | −0.001 | 2.005 |

| Central China | 0.001* | −1.188 | 0.001* | −1.318 | 0.001** | −1.633 |

| Eastern China | −0.011*** | 9.349 | −0.009*** | 11.916 | −0.005*** | 16.114 |

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Contribution of digital engagement to mental health inequalities at different quartiles by gender and urban–rural.

RIF model is set up in detail as follows, and the calculations are completed in Stata17 software using the rifhdreg and oaxaca_rif commands provided by Fernando. 51 Referring to Mao et al., 52 the principle of the RIF regression method is to utilize the RIF of a distribution statistic for regression, expressed as:

| (1) |

In Equation (1), v is the various statistics of the distribution F(y), and IF(Y;v) is the compound regression center of influence function corresponding to a specific statistic Y. The RIF regression is the unconditional quantile regression when the distribution statistic is quantile. The RIF regression is an unconditional quantile regression when the distribution statistics are quantiles. In this case, the RIF regression equation for the Y variable located in the Qt quantile can be written as:

| (2) |

In Equation (2), fY is the marginal density function of Y, and Qt is the unconditional distribution of t quartiles and RIF(Y; v) is expressed linearly as a function of the other explanatory variables. In this study, the unconditional quantile regression equation was constructed as follows when testing the effect of digital engagement on mental health levels at different quantile points in a subgrouped sample (by gender or by urban/rural):

| (3) |

In Equation (3), Qr is the quartile of mental health level and Xi is the variables of digital engagement, socio-demographic characteristics, economic situation, health situation, and residential characteristics. Subsequently, the RIF decomposition was continued to analyze the effects of these variables on subgroup mental health inequalities by constructing a counterfactual function of mental health level. At this point, the subgroup mental health inequalities can be decomposed into two components, namely:

| (4) |

In Equation (4), Mental_healthrow1 and Mental_healthrow2 denote the mental health levels of Group 1 and Group 2, respectively, and Mental_healthc is a function of the counterfactual mental health level, that is the distribution of the counterfactual mental health situation is constructed using the Group 1 characteristic variables with the Group 2 mental health level structure. Equation (3) is substituted into equation (4) to obtain equation (5):

| (5) |

In Equation (5), Xrow1 and Xrow2 denote the elemental characteristic variables of sample Group 1 and sample Group 2, respectively, βrow1 and βrow2 denote the elemental characteristic benefit rates of sample Group 1 and sample Group 2, respectively, and εcrow1 and εcrow2 are the approximation error terms. The first term on the right-hand side of the equation represents the gap in mental health levels due to differences in grouping characteristics, that is the characteristic effect component; the second term measures the gap in mental health levels due to differences in benefit rates when grouping characteristics are the same, that is the parameter effect. 52 In the present study, which also corresponds to digital engagement, the first term on the right side of the middle sign in Equation (5) indicates the mental health inequalities due to differences in digital engagement across gender or across urban and rural residence (what is reported in Table 5, interpretable part); and the second term indicates how differences in the rates of mental health benefits from digital engagement affect gender mental health inequalities or urban and rural mental health inequalities (non-interpretable part).

Results

Descriptive statistics of all variables

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the overall sample, the male and female subsamples, and the rural and urban subsamples. The overall sample consisted of 21,353 individuals, of which the female sample (10,640) was roughly equal to the male sample (10,713), and the rural sample (10,448) was roughly equal to the urban sample (10,905). In terms of Mental health, the male sample had a higher mental health score (0.03) than the female sample (−0.03, principal component scores are essentially standardized values, with negative values indicating only that they are below the overall average), and the urban sample had a higher mental health score (0.03) than the rural sample (−0.04, principal component scores are essentially standardized values, with negative values indicating only that they are below the overall average), and the t-test confirmed the existence of significant gender mental health inequality (t = -12.310, p < 0.000) and urban–rural mental health inequality (t = -13.693, p < 0.000). The mean value of digital engagement was 2.79, with a higher level of digital engagement in the male sample (2.87) than in the female sample (2.71), and a higher level of digital engagement in the urban sample (3.25) than in the rural sample (2.31), showing the same characteristics as mental health. In terms of control variables, the number of male and female samples and urban and rural samples are roughly equal, the average age is 46.60, the number of years of education is 5.11, and 90.62% have at least one type of insurance coverage, but the married sample (87.81%) is much higher than the unmarried sample (12.19%), and the eastern (33.41%) and western (29.53%) samples are much higher than the rest of the regions, and the other characteristics detail the See Table 1.

Global and subsample regression analysis results

After excluding the effects of multicollinearity and controlling for other covariates, a multinomial OLS model was constructed to test the effect of digital engagement on mental health, and the specific results are shown in Table 2. The regression results of the M1 model showed that digital engagement significantly enhanced the mental health of adults (0.011, p < 0.001). In addition, the regression results by gender subsample showed that digital engagement significantly enhanced the mental health level of the female subsample (0.012, p < 0.001) and the male subsample (0.009, p < 0.001), and the positive impact effect was stronger for the female sample. Regression results by rural and urban subsamples showed that digital engagement significantly enhanced mental health levels in the rural subsample (0.014, p < 0.001) and the urban subsample (0.008, p < 0.001), but the positive impact effect was stronger for the rural sample.

In addition, given that the sampling design of the CFPS includes a household clustering feature, that is members within a household may be correlated, this study uses cluster-robust standard errors at the household level to correct for potential correlation problems. This method can effectively address the problem of statistical inference bias due to within-group correlation by allowing the error terms of individuals within the same household to be correlated while maintaining independence across households. 53

Impact of digital engagement on mental health inequalities

This part of the analysis examined the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities using RIF regression models and the results are presented in Table 3. The RIF regression for the M6 model showed that digital engagement mitigated mental health inequalities for the overall sample (−0.018, p < 0.001). It is shown here that a 1-unit increase in average digital engagement (in this case, the level of digital engagement) for all adults in the sample will shrink the difference between the 90th and 10th percentile of mental health by 0.018. Similarly, M7 and M8 models showed that digital engagement mitigated mental health inequalities between the male-female sample (−0.015, p < 0.001) and between the urban–rural sample (−0.018, p < 0.001), respectively. But it is clear that digital engagement has a stronger mitigating effect on mental health inequalities between urban and rural than between male and female.

In order to visualize the effect of digital engagement on mental health of both male and female samples in more detail, this research used RIF regression to measure the effect of digital engagement on mental health at different quartiles and plotted it as Figure 1. Figure 1 shows that the positive effect of digital engagement on mental health is larger for female samples than for male samples at all quartiles, and shows a fluctuating and expanding trend. There is an inflection point from the 40th quartile, in which the effect of digital engagement is consistently stronger in the female sample than in the male sample, especially in the range of 55th quartile to 80th quartile. This suggests that for samples with moderate and high mental health levels, the enhancing effect of digital engagement on female mental health levels is much stronger than that of males. At the same time, the effect of digital engagement on male samples with low mental health levels is stronger. However, it was strong for female samples of all mental health levels, especially for female samples of medium and low mental health levels. This shows that the mitigating effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities between men and women is mainly realized in the 45–80 quantile range.

Similarly, in order to visualize the effect of digital engagement on mental health between the rural and urban samples in more detail, this research continued to use RIF regression to measure the effect of digital engagement on mental health at different quartiles and plotted it as Figure 2. Figure 2 shows that the positive effect of digital engagement on mental health at each quartile is greater for the rural sample than the urban sample, and the overall trend is fluctuating and decreasing. Using the 50th quartile as the cutoff, the gap between the 10th and 50th quartiles decreases, but the gap between the 50th and 90th quartiles increases again. This suggests that the positive effect of digital engagement on mental health in the male sample is stronger in the low mental health sample, which shows a similar trend in the urban sample. It can be seen that the mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequalities is mainly realized in the 10–50 quartile range and 55–80 quartile range.

RIF decomposition of digital engagement’ contribution to mental health inequalities

This part of the analysis used the RIF decomposition method to decompose the characteristic effects of gender mental health inequalities. Table 4 reports the results of the RIF decomposition at the 10th, 50th and 90th quantile. The results show that differences in the characteristic of digital engagement contributed 3.93%, 3.26%, and 2.67% of gender mental health inequality at the 10th, 50th, and 90th quantile. The mitigating effect of digital engagement on gender mental health inequality diminished at the 10th (−0.003, p < 0.01), 50th (−0.002, p < 0.001), and 90th (−0.001, p < 0.01) quartiles in that order, suggesting that differences in the characteristics of digital engagement mitigated gender mental health inequality, and that this mitigating effect was increasing with increasing levels of mental health. Figure 3 shows the characteristic effect of digital engagement on gender mental health inequality measured by RIF decomposition at different quartiles, and it can be seen that this mitigating effect shows a small fluctuating trend.

Based on the same analytical approach, the characteristic effects of urban–rural mental health inequalities were again decomposed using the RIF decomposition method. Table 5 reports the results of the RIF decomposition at the 10th, 50th, and 90th quantile points. These results indicate that the characteristic difference in digital engagement contributes 18.95%, 17.19%, and 19.60% of urban–rural mental health inequality at the 10th, 50th, and 90th quantile points, respectively. Specifically, the mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequality showed a “U” shape at the 10th (−0.022, p < 0.001), 50th (−0.013, p < 0.001), and 90th (−0.006, p < 0.01) quartiles. It proves that digital engagement can alleviate urban–rural mental health inequalities, but this alleviation effect is stronger at the low and high quartiles, and weaker at the middle quantile.

Combined with the mitigating effects at different quartiles of Figure 3, the mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequality reaches its weakest at the 30th quantile, and then has been fluctuating and strengthening, and then exceeds the mitigating effect at the 10th quantile at the 60th quantile, and then shows a fluctuating and strengthening trend. The mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequalities is drastic relative to the mitigating effect on gender mental health inequalities, and the mitigating effect on mental health inequalities is stronger at the higher quartiles relative to the former.

Discussion

Based on the CFPS 2020 wave dataset, this research empirically examines the effects of digital engagement on mental health and mental health inequality among Chinese adults. The research found that: (1) digital engagement positively predicts the mental health of Chinese adults and has a more significant digital “healing” effect in female samples and rural samples; (2) digital engagement significantly alleviates adult mental health inequalities, which including gender mental health inequalities and urban–rural mental health inequalities, with stronger mitigating effects of digital engagement in the latter group; (3) digital engagement's mitigating effect on gender mental health inequalities is mainly realized in the 45–80 quantile range, but digital engagement's mitigating effect on urban–rural mental health inequalities is mainly realized in the 10–50 quantile range and 55–80 quantile range; (4) the characteristic difference of digital engagement can mitigate gender mental health inequalities, and this mitigating effect is gradually weakening with the increase of mental health level; in contrast, the characteristic difference of digital engagement also mitigates urban–rural mental health inequalities, but this mitigating effect is stronger at the lower and higher quartiles compared to at the intermediate quartile.

Digital engagement positively predicts mental health among Chinese adults, including male adults, female adults, and both rural and urban adults, and this positive impact effect is stronger among female and rural groups. Prior research has suggested that the same resources held by dominant groups lead to higher returns, 39 that male groups can derive greater benefits from the Internet compared to female groups, 54 and that improvements in subjective well-being among Internet users have also occurred primarily among residents of large and medium-sized cities. 55 However, this research's findings are inconsistent with this, as adult digital engagement in the Chinese scenario consistently had a higher positive impact effect on women's mental health than men's, and a higher positive impact effect on mental health in the rural sample than in the urban sample.

There is also gender heterogeneity and urban–rural heterogeneity in the effects of digital engagement on the mental health of Chinese adults, that is a more pronounced digital “healing” effect was reported in female samples and rural samples. One possible explanation is that rural and urban samples, and male and female samples differ in their Internet use preferences. 56 Urban residents are more likely to use the Internet for learning and acquiring useful knowledge, whereas rural groups are more likely to use the Internet for leisure and entertainment; women are more likely than men to seek informational help on social media.57–59 Giving and receiving emotional support relieves mental stress from higher levels of social support. 60

Digital engagement can significantly mitigate mental health inequalities among adults, as well as gender mental health inequalities and urban–rural mental health inequalities. Unlike the findings of Spanakis et al., 14 the effect of digital exclusion was not significant among Chinese adults. However, the mitigating effect of digital engagement on urban–rural mental health inequalities was stronger than that of gender mental health inequalities. This is attributed to the unequal access to resources, social services, and information resulting from the particular China's dual urban–rural social structure.61,62 Traditionally, rural areas are characterized by remote locations, lack of medical resources, and inadequate public health services,63,64 resulting in more severe mental health problems among rural residents. Digital engagement, through the Internet and mobile technology, provides opportunities to remedy these inequalities, significantly improving the mental health of rural residents.65–67 In contrast, the marginal effect of digital engagement is relatively small for urban residents, despite having more developed healthcare systems and mental health services, because urban residents are already able to access these services more easily, making digital engagement's contribution to their mental health primarily a complementary function.68,69

In addition, digital engagement exerted its mitigating effects in different ways. It mitigated gender mental health inequalities in the 45–80 quartile range, but mitigated urban–rural mental health inequalities in the 10–50 quartile range and in the 55–80 quartile range. It is also important to note that the mitigating effect of digital engagement on gender mental health inequality was progressively weaker, but there was no such trend for the mitigating effect on urban–rural mental health inequalities. This gap may be due to the difference in the causes of gender mental health inequality, which is mainly due to social roles, gender norms and biological differences, and urban–rural mental health inequality, which is mainly due to uneven distribution of resources and accessibility of public services.

This research also had unexpected findings. Previous research has argued that digital engagement positively mediates the formation of gender and urban–rural mental health inequalities,70,71 thereby amplifying mental health inequalities. As an example, Leguina et al. identified online participation as a form of bridging capital that reproduces and exacerbates levels of inequality in contemporary society by allowing already advantaged users to deploy these resources online and benefit from their economic, cultural and social capital. 72 However, this research found that for groups with digital resource advantages, digital resource advantages did not reinforce each other with other socio-economic status advantages (gender and rural/urban) to produce a magnifying effect. Instead, the digital dividend effect was greater than the digital divide effect. The reason for this may be that the rural and female samples tended to have more scarce initial social resources with lower perceptions of social support compared to the urban and male groups, making their mental health status perhaps more benefited by a wide range of digital engagement activities.

Clearly, these research findings support the resource substitution theory 39 and add new evidence to it, further confirming that digital engagement is increasingly critical to enhancing the mental well-being of those occupying resource disadvantageous positions. Our results are also confirmed in the older adults. 73 At the same time, it also refutes the social dis-placement hypothesis, 42 which states that digital engagement has negative effects on mental health due to the crowding out of more valuable interaction time with family and friends. This inconsistency may come from the intensity of users’ use of digital technology, with excessive/problematic Internet use often detrimental to mental health. Therefore, it should be further noted that the generalizability of the study conclusions is influenced by the researchers’ measurement of digital engagement.

There are limitations to this research. Firstly, this study used the 2020 dataset in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which somewhat limits the external validity of the findings. Secondly, the measure of digital engagement and mental health lacks a well-established scale, which would affect the estimation of the effect of digital engagement on mental health inequalities. Thirdly, because this study used a secondary cross-sectional dataset, potential endogeneity issues were not addressed and are a limitation of the study.

Conclusions

This research explored the association between digital engagement and mental health inequalities based on cross-sectional data from the CFPS wave 2020. The findings validate the positive impact of digital engagement on the mental health level of Chinese adults, while digital engagement effectively mitigates mental health inequalities driven by gender and urban–rural factors. In addition, although the level of digital engagement of the female, rural sample is not as good as that of the male, urban sample, the former can better utilize digital technology to improve their mental health. Based on this, for the public sector, strengthening the construction of digital public infrastructure and enhancing the level of digital engagement, especially for disadvantaged groups, are important policy directions to improve citizens’ mental health and reduce mental health inequalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Institute for Social Science Surveys (ISSS) at Peking University for permission to use the CFPS Wave 2020 dataset. Our sincere thanks are in order to all the respondents who were part of the survey.

Footnotes

Contributorship: Y.W. did conceptualization, framework, model analyses, data curation and writing—original draft. C.L. performed writing—original draft and data curation. Two authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-14010). All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Social Science Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Province [grant number 24ZHC007].

Guarantor: CL.

ORCID iDs: Yangyang Wang https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0300-5125

References

- 1.Ngui EM, Khasakhala L, Ndetei D, et al. Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: a global perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010; 22: 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao Q, Zhang X, Wu Y, et al. Decomposing income-related inequality in health-related quality of life in mainland China: a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Global Health 2023; 8: e013350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nie P, Ding L, Chen Z, et al. Income-related health inequality among Chinese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence based on an online survey. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommet N, Morselli D, Spini D. Income inequality affects the psychological health of only the people facing scarcity. Psychol Sci 2018; 29: 1911–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtze N, Eikemo TA, Kamphuis CBM. Educational inequalities in general and mental health: differential contribution of physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and diet. Eur J Public Health 2013; 23: 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y, Xie H, Huang Z, et al. The mental health of transgender and gender non-conforming people in China: a systematic review. The Lancet Public Health 2021; 6: e954–e969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma L, Huang Y, Liu T. Unequal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: role of the neighborhood environment. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022; 87: 104162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen Y, Ta N, Liu Z. Job-housing distance, neighborhood environment, and mental health in suburban Shanghai: a gender difference perspective. Cities 2021; 115: 103214. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson B, Schneider J, Talamonti D, et al. The impact of inequality on mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 2021; 62: 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu S. Uncovering the hidden impacts of inequality on mental health: a global study. Transl Psychiatry 2018; 8: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8: 981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saltzman LY, Lesen AE, Henry V, et al. COVID-19 mental health disparities. Health Secur 2021; 19: S-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maffly-Kipp J, Eisenbeck N, Carreno DF, et al. Mental health inequalities increase as a function of COVID-19 pandemic severity levels. Soc Sci Med 2021; 285: 114275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spanakis P, Peckham E, Mathers A, et al. The digital divide: amplifying health inequalities for people with severe mental illness in the time of COVID-19. Brit J Psychiat 2021; 219: 529–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrescio-Higa F, Valenzuela P. Gender inequality and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Public Health 2021; 66: 1604220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proto E, Quintana-Domeque C. COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PLOS ONE 2021; 16: e0244419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res 2020; 287: 112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llop-Gironés A, Vračar A, Llop-Gironés G, et al. Employment and working conditions of nurses: where and how health inequalities have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic? Hum Resour Health 2021; 19: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tverdostup M. COVID-19 and gender gaps in employment, wages, and work hours: lower inequalities and higher motherhood penalty. Comp Econ Stud 2023; 65: 713–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaalavuo M, Salokangas H, Tahvonen O. Gender inequality reinforced: the impact of a child’s health shock on Parents’ labor market trajectories. Demography 2023; 60: 1005–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med 2020; 266: 113364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, Li S, Xiao Q, et al. Social support and psychological well-being under social change in urban and rural China. Soc Indic Res 2014; 119: 979–996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Dupre ME, Qiu L, et al. Urban–rural differences in the association between access to healthcare and health outcomes among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Rose N. Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural–urban migrants—a review and call for research. Health Place 2017; 48: 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma C, Song Z, Zong Q. Urban–rural inequality of opportunity in health care: evidence from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan B, Li J, Wang Z, et al. Household registration system, migration, and inequity in healthcare access. Healthcare 2019; 7: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Que J, Lu L, Shi L. Development and challenges of mental health in China. Gen Psychiatr 2019; 32: e100053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haakenstad A, Irvine CMS, Knight M, et al. Measuring the availability of human resources for health and its relationship to universal health coverage for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022; 399: 2129–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan Q. Supporting older people coping in a digital society: comparing case studies in China and Finland. Chin J Soc Work 2023; 16: 166–181. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker I, Easton K, Prestwood R. Digital community assets: investigating the impact of online engagement with arts and peer support groups on mental health during COVID-19. Sociol Health Illn 2023; 45: 666–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forsman AK, Nordmyr J. Psychosocial links between internet use and mental health in later life: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Appl Gerontol 2017; 36: 1471–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi NG, DiNitto DM. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/internet use. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CNNIC. The 53rd statistical report on China’s internet development. Beijing. March, 2024. https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202405/P020240509518443205347.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma C, Song Z, Zong Q. Urban–rural inequality of opportunity in health care: evidence from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen W, Zhang Y, Shi W, et al. Association between internet use and physical health, mental health, and subjective health in middle-aged and older adults: nationally representative cross-sectional survey in China. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e40956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friis-Healy EA, Nagy GA, Kollins SH. It is time to REACT: opportunities for digital mental health apps to reduce mental health disparities in racially and ethnically minoritized groups. JMIR Ment Health 2021; 8: e25456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Przybylko G, Morton D, Morton J, et al. The influence of gender and age on the outcomes of and adherence to a digital interdisciplinary mental health promotion intervention in an australasian nonclinical setting: cohort study. JMIR Ment Health 2021; 8: e29866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaves A, Arnáez S, García-Soriano G. The effectiveness of a cell phone eHealth app in changing knowledge, stigmatizing attitudes, and intention to seek help associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder: pilot questionnaire study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024; 12: e48027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 1400–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Jin G, Guo Y, et al. Internet access, support, usage divides, and depressive symptoms among older adults in China: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 2023; 323: 514–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson MA. Health returns to education by family socioeconomic origins, 1980–2008: testing the importance of gender, cohort, and age. SSM—Popul Health 2016; 2: 549–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bessière K, Kiesler S, Kraut R, et al. Effects of internet use and social resources on changes in depression. Inf Commun Soc 2008; 11: 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golin M. The effect of broadband internet on the gender gap in mental health: evidence from Germany. Health Econ 2022; 31: 6–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z, Song Q, Li J, et al. Air pollution and mental health: the moderator effect of health behaviors. Environ Res Lett 2021; 16: 044005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang D, Hu B, Ren Z, et al. Impact of income on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: based on the 2020 China family panel survey. Front Psychol 2022; 13: 977609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Zhang X, Chen X. Happiness in the air: how does a dirty sky affect mental health and subjective well-being? J Environ Econ Manag 2017; 85: 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zu D, Zhai K, Qiu Y, et al. The impacts of air pollution on mental health: evidence from the Chinese university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 6734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao D, Zhou Z, Liu G, et al. Does social capital buffer or exacerbate mental health inequality? Evidence from the China family panel study (CFPS). Int J Equity Health 2022; 21: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Wang Y. Association between digital engagement and urban–rural disparities in Chinese women’s depressive symptoms: a national-level cross-sectional study. Digit Health 2024; 10: 20552076241239246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Firpo S, Fortin NM, Lemieux T. Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica 2009; 77: 953–973. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rios-Avila F. Recentered influence functions (RIFs) in Stata: RIF regression and RIF decomposition. Stata J 2020; 20: 51–94. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yufei M, Xiangquan Z, Wenxin H. Does internet usage reduce the gender wage gap? Empirical analysis based on CFPS data. Cai-jing Yanjiu 2018; 44: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cameron AC, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour 2015; 50: 317–372. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong J, Wu W, Zhao F. The impact of Internet use on the subjective well-being of Chinese residents: From a multi-dimensional perspective. Front Psychol 2022; 13: 950287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song Q, Smith JP. The citizenship advantage in psychological well-being: an examination of the Hukou system in China. Demography 2021; 58: 165–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J-Y, Bennett K, Probst J. Subdividing the digital divide: differences in internet access and use among rural residents with medical limitations. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: e1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lehdonvirta M, Nagashima Y, Lehdonvirta V, et al. The stoic male: how avatar gender affects help-seeking behavior in an online game. Games Cult 2012; 7: 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol 2003; 58: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krasnova H, Veltri NF, Eling N, et al. Why men and women continue to use social networking sites: the role of gender differences. J Strateg Inf Syst 2017; 26: 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liebler CA, Sandefur GD. Gender differences in the exchange of social support with friends, neighbors, and co-workers at midlife. Soc Sci Res 2002; 31: 364–391. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salemink K, Strijker D, Bosworth G. Rural development in the digital age: a systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J Rural Stud 2017; 54: 360–371. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang X, Yang Y. Invisible China: how the urban–rural divide threatens China’s rise. Soc Justice Res 2024; 37: 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu R, Dong S, Zhao Y, et al. Assessing potential spatial accessibility of health services in rural China: a case study of Donghai county. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Couper I, Walters L, Williams S, et al. Exploring rural doctors’ early experiences of coping with the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. J Rural Health 2022; 38: 923–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Y, Ye Q. The impact of digital governance on the health of rural residents: the mediating role of governance efficiency and access to information. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1419629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kohli K, Jain B, Patel TA, et al. The digital divide in access to broadband internet and mental healthcare. Nat Ment Health 2024; 2: 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy JK, Saker S, Chakraborty PA, et al. Advancing equitable access to digital mental health in the Asia-pacific region in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a modified Delphi consensus study. PLOS Glob Publ Health 2024; 4: e0002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lederbogen F, Kirsch P, Haddad L, et al. City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature 2011; 474: 498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qu D, Liu D, Cai C, et al. Process model of emotion regulation-based digital intervention for emotional problems. Digit Health 2023; 9: 20552076231187476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Long C, Han J, Yi C. Does the effect of internet use on Chinese Citizens’ psychological well-being differ based on their Hukou category? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 6680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nie W, Hu M, Ye X. Internet use and rural–urban mental health inequalities: Evidence from China. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1107146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leguina A, Downey J. Getting things done: inequalities, internet use and everyday life. New Media Soc 2021; 23: 1824–1849. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Z, Li Z. Relationships between digital engagement and the mental health of older adults: evidence from China. PLOS ONE 2024; 19: e0308071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]