Abstract

Background

Compensation plays a critical role in motivating staff and enhancing operational performance and human resource costs in hospitals. This study was aimed at investigating pay levels and the key factors influencing pay satisfaction in secondary and tertiary public hospitals in Guangxi.

Methods

Questionnaires were distributed to 48 hospitals across 14 prefecture-level cities in Guangxi. Information on personal characteristics, salary levels, work situations and perceptions of current salary conditions was provided by 10,343 staff in secondary and tertiary hospitals. Five machine learning models were employed to identify the most significant influencing factors of salary satisfaction in Guangxi public hospitals.

Results

Overall, the actual total after-tax income in secondary public hospitals in Guangxi ranged from $466.55-$744, while the income of staff in municipal-level tertiary public hospitals ranged from $5,001 to $1,041.75 per month. Among the five models, the support vector machine (SVM) demonstrated the best performance in analyzing the influencing factors of compensation satisfaction. The most influential factors for total compensation satisfaction included the extent to which compensation reflected labor value, salary increases since 2017 compared to peer hospitals, total after-tax income and the difference in compensation between staff within and outside the establishment of hospitals. Satisfaction with salary growth aligned closely with the factors influencing overall compensation satisfaction. Satisfaction with pay equity was also influenced by the ability of salary gaps between different positions to reflect differential effort.

Conclusions

A relatively low pay level in secondary hospitals in Guangxi was revealed. The factors influencing satisfaction with total pay, pay fairness and pay growth since 2017 varied. SVM outperformed other models in the analysis of the factors influencing pay satisfaction. To enhance pay satisfaction in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Guangxi, it is crucial to establish a salary distribution system aligned with the value of labor across different positions and tailored to the unique characteristics of each hospital.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-12552-9.

Keywords: Salary satisfaction, Personnel and salary reform, Public hospital, Machine learning

Background

The compensation of medical staff in hospitals is a prominent topic in international health policy academia. Research indicates that compensation levels exert an impact on the turnover intentions of doctors [1, 2] and nurses [3], their choice of employment areas [4] and the quality of career survival of nurses, all of which are related to their satisfaction with compensation [5]. A reasonable compensation structure can significantly motivate medical staff [6], whose satisfaction with compensation is mainly influenced by the gap between their actual compensation and compensation expectations [7]. Additionally, compensation satisfaction is linked to the level of compensation management, and high compensation satisfaction among hospital personnel can improve the operational performance and human resource costs of hospitals [8].

In recent years, reforms have been implemented in Chinese public hospitals [9], with personnel compensation system reforms being a core component. Previously, public hospitals were managed by the government, and salary management remained constrained despite a marked rise in workload and labor volume. The salary structure in public hospitals consists of four components: position, grade and performance-based salaries, and allowances and subsidies. Among them, position and grade salaries constitute the basic wage, while performance-based salaries and allowances represent the incentive-based portion. The state implements overall control and policy guidance, while institutions are granted autonomy to determine the distribution of performance-based salaries within their respective units. In 2006, the basic salary system for public hospitals was based on a position-performance salary framework. Positions were categorized into 13 levels of professional and technical positions, eight levels of managerial positions, and skilled labor positions. Each level corresponded to different salary standards. A total of 65 salary grades were established for professional, technical and managerial staff, while 40 salary grades were set for workers. Each salary grade was associated with a specific wage standard, with different starting salary grades assigned to different positions. Performance-based salaries in public hospitals are issued independently as per standardized allocation procedures and requirements, with flexible and diverse distribution methods. Allowances and subsidies primarily encompass hardship and remote area allowances, special position allowances, and public health and epidemic prevention allowances. In 2009, China refined the distribution of performance-based salaries by implementing a position-performance system, focusing on service quality and quantity, and rewarding key positions. In 2011, further reforms introduced an assessment and incentive mechanism based on service quality, quantity, patient satisfaction and performance. In 2016, the “Two Allowances” policy allowed healthcare institutions to exceed public salary control and used revenue (after costs and required funds) for employee rewards while ensuring equal pay for equal positions to incentivize healthcare workers. Pilot public hospital salary reforms were initiated in key cities such as Sanming, Shanghai and Shenzhen in 2017, and had been deepened by 2021. The salary structure of public hospitals was optimized; the position-performance salary system was improved; new approaches like annual salary systems for hospital leaders and contract-based wage systems were explored. The reforms also implemented the autonomy of performance-based distribution in public hospitals and reflected the differences across various positions, with a particular focus on critical and shortage areas. Furthermore, they promoted equal pay for equal positions, regardless of whether employees were within or outside the official staff structure of hospitals. It was required that public hospitals adopt a variety of methods for the independent distribution of total approved salary. Less developed regions in China, including Xining, Nanchang Changchun, etc., have explored public hospital salary reforms and taken measures like a secondary distribution salary system. The original salary inclination policies of many public hospitals for high-level talent failed to take advantage of market competition, which led to a serious loss of talent and a shortage of high-level talent. In November 2021, a public hospital pay system oriented towards public welfare and adapted to the characteristics of the medical industry was fully implemented in Guangxi. It implemented dynamic rewards based on the total amount of public hospital performance pay and proposed that the main responsible person for public hospitals could implement an annual salary system. At present, public hospitals are allowed to independently determine the scope of high-level (urgent and scarce) talents, pay levels and distribution forms.

This study aimed to examine the status quo of compensation of public hospital staff in China, with a specific focus on less developed regions [2, 3, 10]. While existing studies have explored compensation in developed regions, a gap exists in the literature regarding the compensation of medical staff in these regions. To address this gap, a larger sample size covering both secondary and tertiary hospitals in Guangxi than previous studies was used in the present study. Despite have being utilized in prior research, descriptive statistical analysis or logistic regression [11] may not accurately identify the most important factors influencing compensation satisfaction in public hospitals after compensation reforms. Thus, five machine learning models were utilized in this study to analyze the pay satisfaction of public hospital employees in Guangxi, and to identify the most influential factors of satisfaction with pay structure, increases and fairness after pay reforms. The study aimed to develop improvement strategies consistent with Guangxi and the less developed areas in western China, to enhance the pay satisfaction of healthcare workers in public hospitals.

Methods

Sample and data collection

The cross-sectional sample for this study was collected by the Guangxi Hospital Association from March to December 2022. The convenience sampling method was employed to directly distribute questionnaires to all medical personnel in secondary and tertiary public hospitals in Guangxi through the association. Questionnaires were handed out to employees from 48 public hospitals in 14 prefecture-level cities in Guangxi, including 21 general hospitals and 27 specialty hospitals. In total, 10,442 responses were received, out of which 10,343 were deemed valid. The questionnaire achieved an effective response rate of 99.05%. The sample comprised 9,145 general staff and 1,171 department leaders in 8,519 general hospitals and 1,824 specialty hospitals (like traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) hospitals and maternal and child health hospitals). Specifically, these were 2,475 medical staff, 4,890 nursing staff, 1,526 medical technology staff, 805 administrative staff and 647 logistics staff. The opening section of this study included an informed consent form, and all the medical staff who agreed to participate could complete the online survey once providing their consent.

Questionnaire design

The “Research Questionnaire on the Status of Personnel Compensation Reforms in Guangxi Public Hospitals”, which consisted of four parts, was designed. The first part covered basic personal characteristics such as gender, age, region of the hospital, hospital level, professional category, title and position. The second part contained personal salary situations, including actual total after-tax income, fixed income, variable income, etc. The third part encompassed personal salary satisfaction, including satisfaction with their current salaries, salary increases since 2017 and the percentage of personal factors in their salaries, with the salary unit converted from Renminbi (RMB) to United States dollar (USD). The fourth part included pay-return situations and used the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) scale [12]. Investigators assisted all hospital respondents in filling out the questionnaire, whose reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. In addition, 30 investigators in different positions were interviewed, including two hospital leaders, five department leaders and 23 general employees. Interviews can better help explore the reasons for changes in salary satisfaction in public hospitals since personnel and compensation reforms in 2017.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis described in this paper included both descriptive and inferential statistics. The former was used to summarize the basic information of medical staff, while the latter was used to detect associations between pay satisfaction and demographic variables using the Chi-square test.

Moreover, factors were detected using five different machine learning algorithms, namely logistic regression, random forest, support vector machines (SVM), XGBoost and single hidden layer (SHL) neural network models. These models were evaluated by use of five-fold cross-validation to select the best combination of parameters and compared using accuracy, specificity, sensitivity and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC).

Logistic regression is a kind of generalized linear regression suitable for scenarios in which a classification probability needs to be obtained. It is capable of handling large data with fewer resources, robust to small noise in data and free from the particular influence of minor multicollinearity.

As an integrated classifier built randomly, a random forest contains multiple decision trees. Its output classes are up to individual tree votes. Integrated learning results in low variance and bias and superior generalization performance. Good for high-dimensional datasets, a random forest can handle thousands of input variables to determine the most important ones [13].

XGBoost extends the traditional gradient boosting algorithm that uses a tree model as the base learner and combines the prediction results from each tree to obtain the final prediction results. It boasts higher accuracy and more flexibility and uses regularization to prevent overfitting compared with the traditional gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) algorithm [14].

SVM is a class of generalized linear classifiers that perform binary classification of data by supervised learning. The complexity of computation depends on the number of support vectors rather than the dimensionality of sample space, which thus avoids the “dimensionality disaster” [15].

A SHL neural network model is a neural network composed of one layer of hidden layer nodes and input and output layers. It is a layer of feature hierarchy, where each neuron can be considered as a feature attribute.

Results

Baseline data

In this study, a sample of 10,343 hospital employees was contained. Among them, 2,815 were satisfied and 7,528 were dissatisfied with total remuneration; 3,928 were satisfied and 6,415 were dissatisfied with pay equity; 2,400 were satisfied and 7,943 were dissatisfied with pay increases since 2017.

Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1, with 8,681 respondents from tertiary hospitals and 1,662 from secondary hospitals. The majority of respondents from secondary hospitals were from the eastern region of Guangxi, and the majority of respondents from tertiary hospitals were from the southern region of Guangxi. Most respondents were female. In addition, 56.50% of the respondents were aged below 35; 47.28% of respondents were in the nursing profession; and 23.93% of the respondents were medical staff. Most of the responders were on staff with a bachelor’s degree; 43.59% of the responders were junior staff; 29.90% of the responders were intermediate staff. A majority of responders were general staff, and 56.94% of the responders had been working for less than 10 years. Besides, 52.83% of secondary hospital staff worked an average of eight hours or less per day; 87.21% of tertiary hospital staff worked an average of 8–12 h; 57.11% of hospital employees worked five days or less per week.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| Item | Secondary hospitals (N = 1662) | Tertiary hospitals (N = 8681) | Total (N = 10343) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Type | |||

| General Hospital | 396(23.83%) | 2267(26.11%) | 2663(25.75%) |

| Specialist Hospitals | 1266(76.71%) | 6414(73.89%) | 7680(74.25%) |

| Geographic location | |||

| North | 202(12.15%) | 137(1.58%) | 339(3.28%) |

| Central | 13(0.78%) | 564(6.50%) | 577(5.58%) |

| West | 143(8.60%) | 943(10.86%) | 1086(10.50%) |

| East | 999(60.11%) | 1145(13.19%) | 2144(20.73%) |

| South | 305(18.35%) | 5892(67.87%) | 6197(59.91%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 396(23.83%) | 2267(26.11%) | 2663(25.75%) |

| Female | 1266(76.17%) | 6414(73.89%) | 7680(74.25%) |

| Age | |||

| Under 35 years old | 873(52.53%) | 4971(57.26%) | 5844(56.50%) |

| 35–44 years old | 479(28.82%) | 2547(29.34%) | 3026(29.26%) |

| 45–54 years old | 273(16.43%) | 971(11.19%) | 1244(12.03%) |

| 55 years old and above | 37(2.23%) | 192(2.21%) | 229(2.21%) |

| Type of profession | |||

| Medical | 363(21.84%) | 2112(24.33%) | 2475(23.93%) |

| Nursing | 830(49.94%) | 4060(46.77%) | 4890(47.28%) |

| Medical technology | 242(14.56%) | 1284(14.79%) | 1526(14.75%) |

| Administration | 94(5.66%) | 711(8.19%) | 805(7.78%) |

| Logistics | 133(8.00%) | 514(5.92%) | 647(6.26%) |

| Establishment | |||

| On staff | 930(55.96%) | 5483(63.16%) | 6413(62.00%) |

| Non-staff | 732(44.04%) | 3198(36.84%) | 3930(38.00%) |

| Education | |||

| Secondary school and below | 123(7.40%) | 197(2.27%) | 320(3.09%) |

| College | 655(39.41%) | 1722(19.84%) | 2377(22.98%) |

| Undergraduate | 877(52.77%) | 5919(68.18%) | 6796(65.71%) |

| Master | 7(0.42%) | 843(9.71%) | 850(8.22%) |

| Title | |||

| Not yet assessed | 251(15.10%) | 881(10.15%) | 1132(10.94%) |

| Junior | 763(45.91%) | 3746(43.15%) | 4509(43.59%) |

| Intermediate | 432(25.99%) | 2661(30.65%) | 3093(29.90%) |

| Associate | 201(12.09%) | 1228(14.15%) | 1429(13.82%) |

| Full High | 15(0.90%) | 165(1.90%) | 180(1.74%) |

| Position | |||

| Head of Hospital | 8(0.48%) | 19(0.22%) | 27(0.26%) |

| Head of Department | 206(12.39%) | 965(11.12%) | 1171(11.32%) |

| General staff | 1448(87.12%) | 7697(88.66%) | 9145(88.42%) |

| Length of time in the job | |||

| Less than 10 years | 856(51.50%) | 5033(57.98%) | 5889(56.94%) |

| 11–20 years | 476(28.64%) | 2357(27.15%) | 2833(27.39%) |

| 21–30 years | 243(14.62%) | 942(10.85%) | 1185(11.46%) |

| 31 years or more | 87(5.23%) | 349(4.02%) | 436(4.22%) |

| Average working hours per day | |||

| Up to 8 h | 878(52.83%) | 924(10.64%) | 8298(80.23%) |

| 8–12 h | 784(47.17%) | 7514(87.21%) | 1802(17.42%) |

| 12 h or more | 0(0.00%) | 243(2.80%) | 243(2.35%) |

| Number of working days per week | |||

| 5 days and below | 776(46.69%) | 5131(59.11%) | 5907(57.11%) |

| 5–6 days (excluding 5 days) | 597(35.92%) | 2331(26.85%) | 2928(28.31%) |

| 6–7 days (excluding 6 days) | 289(17.38%) | 1219(14.04%) | 1508(14.58%) |

It can be observed that both tertiary general and specialist hospitals offered higher salary ranges ($744.15-$1,041.6) compared to secondary hospitals ($446.55-$744). Sex-based differences were notable. Males in secondary hospitals earned higher salaries ($744.15-$1,041.6) compared to females ($446.55-$744), but both genders in tertiary hospitals earned similar salaries ($744.15-$1,041.6). Age also influences compensation. Employees at the age of 45 and above earned higher salaries, particularly in tertiary hospitals ($1,041.75-$1,339.2). In terms of professional categories, medical staff in tertiary hospitals earned the highest salaries ($1,041.75-$1,339.2), followed by nursing and medical technology staff. Administrative and logistics staff generally earned less, with logistics staff in secondary hospitals earning the lowest ($446.55-$744). Respondents in secondary and tertiary hospitals exhibited varying compensation levels based on their establishment status, education levels, professional titles, positions and length of time in the job. Detailed information is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Compensation levels of respondents in secondary and tertiary hospitals

| Item | Secondary hospital | Tertiary hospital |

|---|---|---|

| Average annual salary range | Average annual salary | |

| Hospital Type | ||

| General Hospital | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Specialist Hospitals | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Geographic location | ||

| North | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Central | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| West | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| East | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| South | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 744.15–1041.6 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Female | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Age | ||

| Under 35 years old | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| 35–44 years old | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| 45–54 years old | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| 55 years old and above | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| Type of profession | ||

| Medical | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| Nursing | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Medical technology | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Administration | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Logistics | 446.55–744 | 446.55–744 |

| Establishment | ||

| On staff | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| Non-staff | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Education | ||

| Secondary school and below | 446.55–744 | 446.55–744 |

| College | 446.55–744 | 446.55–744 |

| Undergraduate | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Master | 744.15–1041.6 | 1339.35–1636.8 |

| Title | ||

| Not yet assessed | 446.55–744 | 446.55–744 |

| Junior | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Intermediate | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Associate | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| Full High | 1041.75–1339.2 | 1934.55–2232 |

| Position | ||

| Head of Hospital | 1041.75–1339.2 | 1934.55–2232 |

| Head of Department | 744.15–1041.6 | 1339.35–1636.8 |

| General staff | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| Length of time in the job | ||

| Less than 10 years | 446.55–744 | 744.15–1041.6 |

| 11–20 years | 446.55–744 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| 21–30 years | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

| 31 years or more | 744.15–1041.6 | 1041.75–1339.2 |

In this study, 29.27% of the respondents reported a monthly net actual total income of $446.55 to $744.00, while 29.00% reported a monthly net actual total income of $744.15 to $1,041.60. Among them, 50.30% of the respondents from level II hospitals reported a monthly net actual total income of $446.55 to $744.00, and 30.47% from level III hospitals reported a monthly net actual total income of $744.15 to $1,041.60, as shown in Table 3. Furthermore, 59.90% of the respondents reported a monthly fixed income of $297.75 to $595.20, while 32.59% reported a monthly variable income of less than $297.60. Among the respondents from level II hospitals, 45.85% reported a monthly variable income of $297.75 to $595.20, whereas 31.01% of the respondents from level III hospitals reported a monthly variable income of less than $297.60. More than that, 31.51% of the respondents reported a monthly variable income of $297.75 to $595.20. The respondents mostly believed that the salaries of healthcare professionals should be two to three times the average societal wage ($837 per month). Beyond that, 66.69% of the respondents expressed that the highest and lowest salaries within the same department differed by a factor of 0.5–1. Furthermore, 25.98% of the respondents considered that physicians with intermediate professional titles (attending physicians) earned an annual income (after tax) of $22,320 to $29,760. In addition, 23.06% of the respondents held that nurses with junior professional titles (nurse practitioners) should earn an annual income (after tax) of $8,928 to $11,904. Moreover, 46.21% of the respondents thought that pay parity existed between employees within and outside the official staffing structure of hospitals. Among the respondents from level II hospitals, 43.98% perceived slight differences in salary between employees within and outside the official staffing structure of hospitals, whereas 49.31% of the respondents from level III hospitals believed in pay parity between these groups. Furthermore, 73.16% of the respondents from level II hospitals reckoned that their effort was rewarded favorably, while 68.09% of the respondents from level III hospitals perceived an imbalance in the reward they received for their effort. The majority of staff working in secondary and tertiary public hospitals expressed dissatisfaction with the total amount of compensation, fairness in its distribution and the growth of their salaries.

Table 3.

Respondents’ basic salary information and views on hospital personnel compensation

| Item | Secondary hospitals (N = 1662) | Tertiary hospitals (N = 8681) | Total (N = 10343) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Your actual gross monthly income after tax ($) is (including salary, bonus, allowances, subsidies, etc.) | |||

| Less than $446.40 | 319(19.19%) | 545(6.28%) | 864(8.35%) |

| 446.55 - $744 | 836(50.30%) | 2191(25.24%) | 3027(29.27%) |

| 744.15 - $1041.6 | 354(21.30%) | 2645(30.47%) | 2999(29.00%) |

| 1041.75-$1339.2 | 101(6.08%) | 1645(18.95%) | 1746(16.88%) |

| More than $1339.35 | 52(3.13%) | 1655(19.06%) | 1707(16.50%) |

| Your fixed monthly income ($) is | |||

| Less than $297.6 | 527(31.71%) | 2366(27.25%) | 2893(27.97%) |

| 297.75-$595.2 | 934(56.20%) | 5261(60.60%) | 6195(59.90%) |

| 595.35-$892.8 | 170(10.23%) | 756(8.71%) | 926(8.95%) |

| Above $892.95 | 31(1.87%) | 298(3.43%) | 329(3.18%) |

| Your variable income per month ($) is | |||

| Below $297.6 | 679(40.85%) | 2692(31.01%) | 3371(32.59%) |

| 297.75-$595.2 | 762(45.85%) | 2497(28.76%) | 3259(31.51%) |

| 595.35-$892.8 | 169(10.17%) | 1702(19.61%) | 1871(18.09%) |

| Above $892.95 | 52(3.13%) | 1790(20.62%) | 1842(17.81%) |

| How many times the average social wage ($837/month) do you think it is reasonable for medical staff to be paid | |||

| 2–3 times | 1511(90.91%) | 7092(81.70%) | 8603(83.18%) |

| 4–5 times | 121(7.28%) | 1337(15.40%) | 1458(14.10%) |

| 6 times or more | 30(1.81%) | 252(2.90%) | 282(2.73%) |

| What do you think is a reasonable difference between the highest and lowest total salaries for staff in the same department: | |||

| 0.5–1 times | 1162(69.92%) | 5736(66.08%) | 6898(66.69%) |

| 1.1–2 times | 342(20.58%) | 2080(23.96%) | 2422(23.42%) |

| 2.1–3 times | 118(7.10%) | 595(6.85%) | 713(6.89%) |

| 3.1–4 times | 22(1.32%) | 157(1.81%) | 179(1.73%) |

| 4 times or more | 18(1.08%) | 113(1.30%) | 131(1.27%) |

| For your personal opinion, what is the annual income (after tax) salary of a mid-level (attending) doctor working in our hospital in one year | |||

| Less than $11,904 | 198(11.91%) | 530(6.11%) | 728(7.04%) |

| US$11,904-$14,880 | 240(14.44%) | 633(7.29%) | 873(8.44%) |

| US$14,880-US$17,856 | 364(21.90%) | 1081(12.45%) | 1445(13.97%) |

| 17,856-$22,320 | 337(20.28%) | 1645(18.95%) | 1982(19.16%) |

| 22,320-$29,760 | 350(21.06%) | 2337(26.92%) | 2687(25.98%) |

| US$29,760-US$37,200 | 112(6.74%) | 1443(16.62%) | 1555(15.03%) |

| Above US$37,200 | 61(3.67%) | 1012(11.66%) | 1073(10.37%) |

| In your personal opinion, what should be the approximate annual income (after tax) of a junior title nurse (nurse practitioner) working in our hospital in a year of $10,000 | |||

| Less than US$8928 | 605(36.40%) | 1606(18.50%) | 2211(21.38%) |

| 8928-$11,904 | 506(30.45%) | 1879(21.64%) | 2385(23.06%) |

| US$11,904 - US$14,880 | 305(18.35%) | 1878(21.63%) | 2183(21.11%) |

| US$14,880-US$17,856 | 169(10.17%) | 1672(19.26%) | 1841(17.80%) |

| 17,856-$22,320 | 61(3.67%) | 1155(13.30%) | 1216(11.76%) |

| US$22,320-US$29,760 | 16(0.96%) | 491(5.66%) | 507(4.90%) |

| US$29,760 and above | 605(36.40%) | 1606(18.50%) | 2211(21,38%) |

| Is there a difference in the treatment of staff within and outside the hospital establishment | |||

| There is a big difference | 432(25.99%) | 897(10.33%) | 1329(12.85%) |

| Somewhat different | 731(43.98%) | 3503(40.35%) | 4234(40.94%) |

| Equal pay for equal work | 499(30.02%) | 4281(49.31%) | 4780(46.21%) |

| Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) scale | |||

| Pay-reward imbalance | 988(59.45%) | 5911(68.09%) | 6899(66.70%) |

| Favorable conditions | 1216(73.16%) | 5028(57.92%) | 6244(60.37%) |

| Balance of pay and reward | 198(11.91%) | 768(8.85%) | 966(9.34%) |

| Are you satisfied with your current total compensation? | |||

| Satisfied | 305(18.35%) | 2510(28.91%) | 2815(27.22%) |

| Dissatisfied | 1357(81.65%) | 6171(71.09%) | 7258(70.17%) |

| Are you satisfied with the current fairness of pay distribution? | |||

| Satisfied | 570(34.30%) | 3358(38.68%) | 3928(37.98%) |

| Dissatisfied | 1092(65.70%) | 5323(61.32%) | 6415(62.02%) |

| Are you satisfied with the salary increases since 2017? | |||

| Satisfied | 278(16.73%) | 2122(24.44%) | 2400(23.20%) |

| Dissatisfied | 1384(83.27%) | 6559(75.56%) | 7943(76.80%) |

Factors influencing pay satisfaction

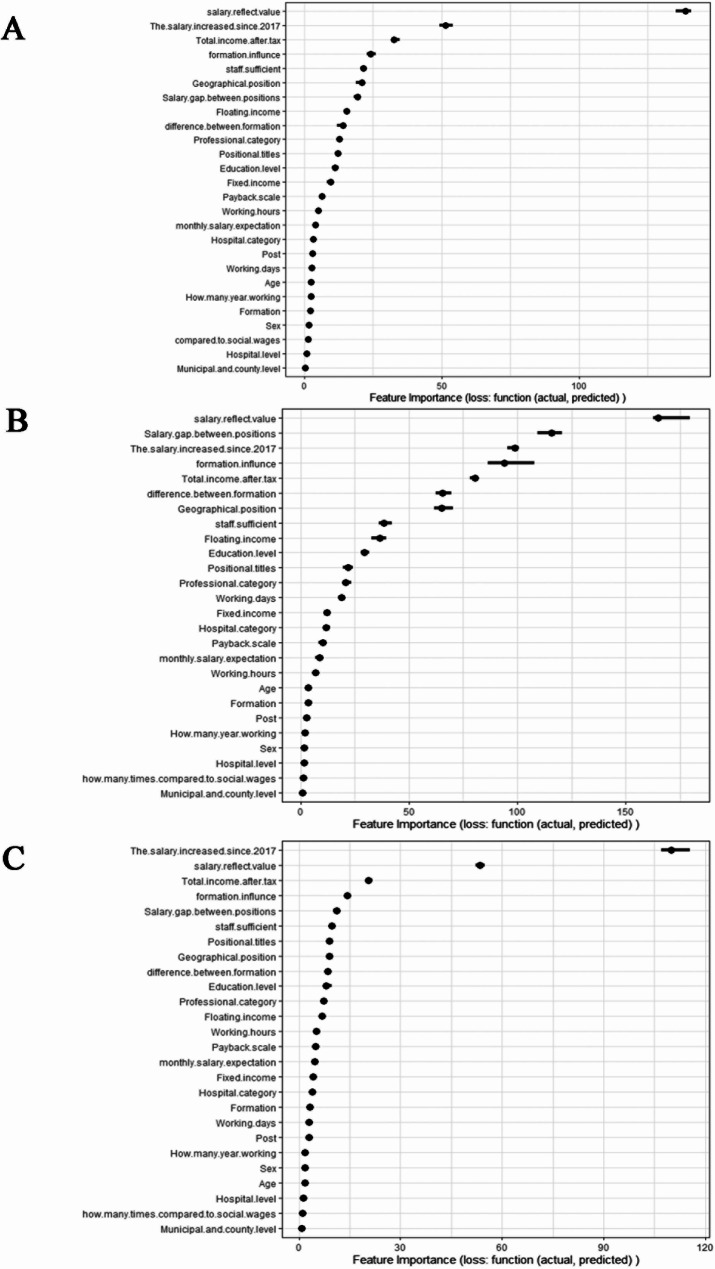

In this study, the SVM model demonstrated the best performance in analyzing the influencing factors of compensation satisfaction. According to the results of SVM in Fig. 1A, SVM analysis identified the key factors (feature importance > 23) as the extent to which salary reflected the value of labor, salary increases since 2017 compared to similar hospitals at the same level, total after-tax income and the difference in compensation between staff within and outside the establishment of hospitals. The important variables of other models can be found in Additional files 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Variable importance of satisfaction with total pay, satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution, and satisfaction with pay growth since 2017 using SVM. Note: A represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding total pay, B represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, and C represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using SVM

Satisfaction with the fairness of salary distribution is demonstrated in Fig. 1B. The SVM model analysis highlighted the most important factors (feature importance > 80) for satisfaction with the fairness of salary distribution. These factors included the extent to which salary reflected the value of labor, the ability of salary gaps between different positions to reflect the differential effort, and salary increases since 2017 compared to similar hospitals at the same level.

Satisfaction with salary increases is presented in Fig. 1C. The SVM model analysis revealed that the key factors (feature importance > 15) affecting satisfaction with pay growth were salary increases since 2017 compared to peer hospitals, the extent to which pay reflected the value of labor, and total after-tax income.

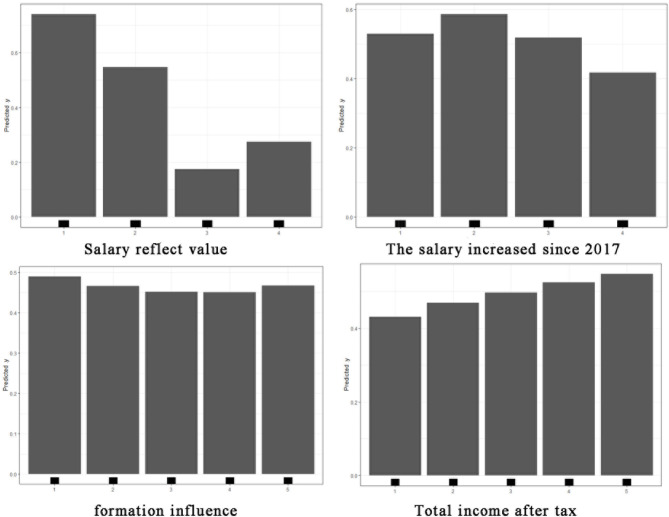

In the current study, the results of SVM were used to generate partial dependence plots for the following variables: total pay satisfaction, pay distribution and satisfaction with salary increases since 2017. When the compensation of medical staff reflected the value of their labor, their satisfaction with total compensation was higher. Additionally, medical staff with slight salary increases and those with increases or significant increases were more likely to feel satisfied with total pay. Medical staff perceiving the impact of formation on their compensation levels as “very significant” or “quite significant” tended to be satisfied with their total compensation. Medical staff with higher after-tax earnings had a higher possibility of being satisfied with their total pay, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The six primary factors influencing total pay satisfaction, visualized using the iml package. Note: The variable “Salary Reflect Value” is divided into four levels:1 - Fully reflects work value, 2 - Partially reflects, 3 - Barely reflects, 4 - Does not reflect at all. The variable “The Salary Increased Since 2017” is divided into four levels:1 - Significant increase, 2 - Moderate increase, 3 - Slight increase, 4 - No increase. The variable “Total Income After Tax” is divided into five levels:1 - Below $466.40, 2 - 466.55 -$744, 3 - 744.15 - $1041.6, 4 - 1041.75 - $1339.2, 5 - Above $1339.35. The variable “Formation Influence” is divided into five levels:1 - Very significant, 2 - Quite significant, 3 - Moderate, 4 - Not very significant, 5 - No influence

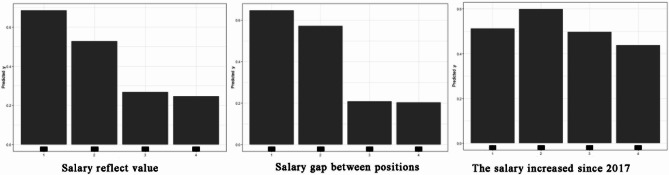

As illustrated in Fig. 3, medical staff whose compensation fully or partially reflected their work value were more likely to be satisfied with pay fairness. Additionally, medical staff who considered that salary differences fully or basically reflected their labor income were also more likely to be satisfied with pay fairness. Furthermore, medical staff who have experienced significant, moderate or slight increases in compensation since 2017 were prone to be satisfied with pay fairness.

Fig. 3.

The five primary factors influencing satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution. Note: The variable “Salary Reflect Value” is divided into four levels: 1 - Fully reflects work value, 2 - Partially reflects work value, 3 - Barely reflects work value, 4 - Does not reflect work value at all. The variable “Salary Gap Between Positions” is divided into four levels: 1- Fully reflects labor income, 2 - Mostly reflects labor income, 3 - Barely reflects labor income, 4 - Does not reflect labor income at all. The variable “The Salary Increased Since 2017” is divided into four levels: 1 - Significant increase, 2 - Moderate increase, 3 - Slight increase, 4 - No increase

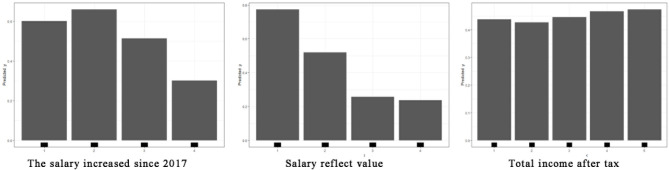

Medical staff who have experienced significant, moderate, or slight salary increases since 2017 are more likely to be satisfied with these salary increases. Additionally, medical staff whose current pay fully reflects the value of their labor are more likely to report higher satisfaction with pay increases since 2017. Furthermore, medical staff with higher after-tax earnings are more likely to be satisfied with their salary increases since 2017, see Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The six primary factors influencing satisfaction with salary increases since 2017. Note: The variable “The Salary Increased Since 2017” is divided into four levels: 1 - Significant increase, 2 - Moderate increase, 3 - Slight increase, 4- No increase. The variable “Salary Reflect Value” is divided into four levels: 1 - Fully reflects work value, 2 - Partially reflects work value, 3 - Barely reflects work value, 4 - Does not reflect work value at all. The variable “Total Income After Tax” is divided into five levels: 1 - Below $446.40, 2 - 466.55 - $744, 3 - 744.15 - $1041.6, 4 - 1041.75- $1339.2, 5 - Above $1339.35

The comparison of the predictive performance of various models in Table 4 showed that the predictive performance of different models for the overall salary satisfaction of staff in Guangxi public hospitals varied. The results indicated that SVM exhibited the highest performance in total satisfaction and achieved a maximum AUC, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of 1.00, 0.999, 0.999 and 1.00, respectively, in the training set. Logistic regression showed comparable performance to SVM in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and AUC, with slightly lower values in the training set. Random forest demonstrated slightly lower performance than logistic regression in the training set, whereas the SHL neural network model performed lower than random forest. XGBoost showed the lowest performance among all the models in the training set.

Table 4.

Comparing the performance of different models in predicting salary total satisfaction

| Total income satisfaction | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | ||||

| Train | 0.949 | 0.955 | 0.934 | 0.975 |

| Test | 0.914 | 0.941 | 0.842 | 0.950 |

| Random forest | ||||

| Train | 0.918 | 0.925 | 0.911 | 0.972 |

| Test | 0.802 | 0.797 | 0.804 | 0.892 |

| SVM | ||||

| Train | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Test | 0.784 | 0.817 | 0.696 | 0.858 |

| Xgboost | ||||

| Train | 0.817 | 0.746 | 0.888 | 0.907 |

| Test | 0.788 | 0.754 | 0.881 | 0.913 |

| SHL | ||||

| Train | 0.859 | 0.837 | 0.919 | 0.952 |

| Test | 0.800 | 0.802 | 0.793 | 0.895 |

As shown in Table 5, the findings revealed that SVM exhibited the highest level of satisfaction with the fairness of pay distribution and achieved an accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of 0.999 and an AUC of 1.00. Subsequently, the SHL neural network approach demonstrated slightly lower performance compared to the SVM neural network model, with an accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and AUC of 0.961, 0.963, 0.959 and 0.990, respectively. Random forest showed inferior performance to the SHL neural network model, while XGBoost and logistic regression exhibited the lowest levels of performance in this regard.

Table 5.

Comparing the performance of different models in predicting satisfaction with pay equity

| Structure satisfaction | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | ||||

| Train | 0.767 | 0.716 | 0.816 | 0.841 |

| Test | 0.746 | 0.705 | 0.813 | 0.833 |

| Random forest | ||||

| Train | 0.856 | 0.847 | 0.864 | 0.933 |

| Test | 0.764 | 0.729 | 0.785 | 0.829 |

| SVM | ||||

| Train | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.00 |

| Test | 0.718 | 0.765 | 0.642 | 0.761 |

| Xgboost | ||||

| Train | 0.766 | 0.789 | 0.743 | 0.842 |

| Test | 0.761 | 0.768 | 0.751 | 0.836 |

| SHL | ||||

| Train | 0.961 | 0.963 | 0.959 | 0.990 |

| Test | 0.687 | 0.709 | 0.651 | 0.731 |

As shown in Table 6, the findings indicated that SVM exhibited superior performance in terms of satisfaction with pay growth and demonstrated an accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of 0.999 and an AUC of 1.00. The SHL neural network model demonstrated slightly lower accuracy, sensitivity and specificity in comparison with SVM while maintaining the same AUC as SVM. Random Forest showed comparatively lower overall performance than the SHL neural network model, and logistic regression exhibited even poorer overall performance. XGBoost and logistic regression demonstrated inferior overall performance as well.

Table 6.

Comparing the performance of different models in predicting satisfaction with pay growth

| Grow satisfaction | Accuracy | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | ||||

| Train | 0.836 | 0.813 | 0.860 | 0.917 |

| Test | 0.816 | 0.808 | 0.843 | 0.908 |

| Random forest | ||||

| Train | 0.904 | 0.916 | 0.892 | 0.970 |

| Test | 0.824 | 0.808 | 0.829 | 0.902 |

| SVM | ||||

| Train | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.00 |

| Test | 0.832 | 0.966 | 0.388 | 0.862 |

| Xgboost | ||||

| Train | 0.839 | 0.779 | 0.900 | 0.920 |

| Test | 0.797 | 0.773 | 0.878 | 0.910 |

| SHL | ||||

| Train | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.997 | 1.00 |

| Test | 0.778 | 0.811 | 0.668 | 0.813 |

Discussion

In this study, the salary levels of medical personnel across various professional categories in secondary and tertiary public hospitals in Guangxi were examined. The average salary ranges in different hospital tiers within Guangxi exhibited variations. Secondary and tertiary hospitals showed disparities in salary levels based on gender, age, professional category, establishment status, title, position and length of service. In the aspect of professional categories, medical staff received the highest salaries. However, the salary gaps among nursing, medical technology, administration and logistics staff were relatively small, which can easily affect the salary satisfaction of nurses. On-staff employees earned significantly higher salaries than non-staff ones, which potentially caused disparities in job satisfaction and perceived value. Similarly, education levels and professional titles were strongly correlated with higher compensation, particularly for medical staff with advanced degrees or senior titles, which may enhance satisfaction due to the recognition of their expertise and qualifications. Moreover, the length of time in the job and age showed a positive correlation with compensation, which may foster loyalty and satisfaction among long-term employees.

On average, the real total after-tax income in secondary public hospitals in Guangxi ranged from US$446.55 to US$744 per month. In tertiary public hospitals, the corresponding range was US$744.15-US$1,041.6 per month at the municipal level and US$446.55-US$744 per month at the county level. The average salary of healthcare professionals in tertiary hospitals ranged from US$1041.75 to US$1,339.2, while that in secondary hospitals ranged from US$744.15 to US$1,041.6. The findings align closely with the 2021 Clove China Hospital Salary Report, which reported an average monthly salary of US$1136.68 for non-tier 1 cities in China, but salaries in secondary hospitals fell below the average salary levels in non-tier 1 cities. Moreover, the results of a 2018 study [16] by Zhang and Zhu on county-level public TCM hospitals in Guangxi from 2013 to 2015 indicated that the average monthly salary in county-level TCM hospitals was 4,967 yuan in 2015 [17]. These findings are in line with the salary levels reported in the current study for 2021. In 2022, Medscape published a survey on the pay of US physicians and revealed higher salary levels for US physicians. The 2018 report indicated that the average monthly income of US physicians reached $24,917, and their average annual income in 2022 was $29,333 despite the influence of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which reflected a pay increase of 17.7%. It is anticipated that these levels will continue to rise in the future. Salary-based specialists in Denmark earned an annual income of US$127,356.86 in 2013 [18], while self-employed specialists in Canada earned an average income of US$212,940.76 per year in 2010. Although the remuneration levels of tertiary hospital staff in Guangxi generally fall within the middle to upper range, a gap remains between them and medical staff in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

Previous research has demonstrated that several factors [11, 19] have a tremendous influence on salary satisfaction, including hospital and job categories, education, establishment and age. As far as employees in public hospitals are concerned, the salary system, salary level, performance allocation and salary structure are considered crucial determinants of their satisfaction [20]. In this study, the focus was on identifying the most important factors influencing overall compensation satisfaction. It was found that a few factors had the most significant influence on overall compensation satisfaction. These factors were the extent to which compensation reflected the value of labor, salary increases since 2017 compared to similar hospitals at the same level, actual total after-tax income, and the difference in compensation between staff within and outside the establishment of hospitals. Regarding satisfaction with salary growth, influential factors are closely aligned with those that affect overall compensation satisfaction.

Presently, a majority of public hospital staff in Guangxi express dissatisfaction with their total remuneration. In their opinion, their compensation should be two to three times higher than the average social wage ($837/month). Given the high educational requirements and technical nature of the medical industry, it is essential to establish a more comprehensive performance-based salary system where public hospital staff are compensated based on the value of their labor. Furthermore, attention must be paid to the relatively low remuneration levels and stagnant growth observed in secondary hospitals since 2015. This is particularly crucial for county-level secondary hospitals. The reason is that the enhancement of the pay structure will attract more talented individuals and serve as a motivator for personnel retention and development in these areas.

As regards salary structure, it was observed that the fixed salary of staff in tertiary hospitals surpassed the variable income, while that of staff in secondary hospitals equaled or exceeded the variable income. This finding is congruent with the 2022 report by Dingxiang Garden, and serves to mitigate the “over-medication” behavior of doctors excessively focused on performance indicators. Reforms are continuously carried out on the medical pricing mechanism, zero-markup drug policies and medical insurance payment, and the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system is being deepened. Against this backdrop, it becomes crucial to develop a rational performance allocation plan within the healthcare industry to enhance the satisfaction of public hospital staff with their salaries. The recently published “Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health System” by the State Council emphasizes the core principle of performance allocation as “more work, more pay; better work, better pay and greater fairness”.

In this study, it was revealed that the key factor influencing satisfaction with salary fairness lies in whether salary can effectively mirror the value of labor and the ability of salary gaps between different positions to reflect differential effort. Furthermore, factors like salary increases since 2017 compared to similar positions in hospitals of the same level and the existence of performance incentives also play a significant role. In interviews, it was discovered that the new wave of the COVID-19 pandemic has induced changes in patient behavior, which leads to a decline in healthcare service utilization and a subsequent reduction in medical revenue. Simultaneously, an increase has taken place in the costs associated with epidemic prevention and control. Consequently, public hospitals have been operating at a financial loss for several years, with minimal growth and sometimes a decline in medical performance. Nevertheless, physicians’ expectations regarding performance-based compensation after the pandemic continue to rise. Moreover, the equalized salary classification of different positions within hospitals has resulted in egalitarianism in salary distribution. To address these issues, it is critical to educate medical personnel about hospital performance allocation policies and keep deepening reforms in the hospital salary system. Reference can be made to the “salary by position” practice at the First Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University to optimize the salary system for non-clinical staff. This entails aligning the positions of non-clinical staff in a more rational and subdivided manner and considers factors like the level of influence and contribution of each role to hospitals. The income gap between positions rather than within the same position can be widened by determining salary, benefits, insurance and provident fund standards based on the technical content, job responsibilities and workload of each position. Additionally, salary increments within the same position can be tied to factors such as years of service, professional qualifications and performance evaluations. Finally, general labor positions within the logistics department can be compensated using standardized industry norms [21].

This study has several limitations. The convenience sampling method was adopted to evaluate the salary satisfaction of medical personnel in secondary and tertiary public hospitals in Guangxi. However, it is important to acknowledge that the sensitivity of salary surveys and related data, potential issues with respondent cooperation, as well as financial and time constraints limiting a comprehensive survey may have introduced certain biases into the study sample. No further spatial difference analysis was conducted based on the location of hospitals.

Conclusion

In this study, the relatively low pay level observed in secondary hospitals in Guangxi was highlighted. Furthermore, distinct influencing factors for satisfaction with total pay, pay distribution fairness and pay growth since 2017 were identified. Through the analysis of the factors influencing pay satisfaction, SVM emerged as the most effective method. To enhance pay satisfaction in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Guangxi, it is vital to undertake comprehensive reforms in the personnel pay system of public hospitals. These reforms should be guided by the principle of aligning compensation with labor value for employees in Guangxi public hospitals. In addition, the establishment of a salary distribution system that accounts for the labor value of staff in different positions and responds to the unique characteristics of hospitals is warranted. These efforts aim to promote greater pay satisfaction among employees and improve the overall working environment in Guangxi public hospitals.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Variable importance of satisfaction with total pay, satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution, and satisfaction with pay growth since 2017 using Logistic regression and random forest. NOTE: A represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by Logistic regression, B represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by Random forest, C represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by Logistic regression, D represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by Random forest, E represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using Logistic regression, and F represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using Random forest.

Additional file 2. Variable importance of satisfaction with total pay, satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution, and satisfaction with pay growth since 2017 using XGboost and SHL. NOTE: A represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by XGboost, B represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by SHL, C represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by XGboost, D represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by SHL, E represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using XGboost, and F represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using SHL.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Guangxi Medical Union which organized this research, and We would also like to thanks the hospital staff who respond to this questionnire.

Abbreviations

- XGboost

Extreme Gradient Boosting

- SVM

Support Vector Machines

- SHL

Single hidden layer neural network

Authors' contributions

XY and PZ conceived and designed the study. XY conducted the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical appraisal and finalizing of the manuscript. All the authors critically read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from The Guangxi Higher Education Institution’s Cultivation Plan for One Thousand Young and Middleaged Key Teachers in Humanities and Social Sciences Project Approval Program: Research on the Remuneration Incentive Mechanism for Medical Staff in Primary Healthcare Institutions in Ethnic Areas (Grant Number: 2023QGRW015).

Data availability

The distribution of the data files is restricted by the written consent of the participating investigators. Researchers who want access to the data may contact the corresponding author, who will determine whether the requested data may be made available in a form that does not violate the written consent.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University (approval number: KY20240323). A statement explaining the informed consent to participate was included on the opening page of the survey. The participants were only able to complete the online questionnaire after accepting the terms of consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhong Tang, Email: tangzhong@stu.gxmu.edu.cn.

Pinghua Zhu, Email: zhupinghua@gxmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lu Y, Hu X, Huang X, Zhuang X, Guo P, Feng LF, et al. The relationship between job satisfaction, work stress, work–family conflict, and turnover intention among physicians in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Z, Xie Z, Dai J, Zhang L, Huang Y, Chen B. Physician burnout and its associated factors: A Cross-sectional study in Shanghai. J Occup Health. 2014;56(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam A, Asim M. Relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. Int J Hum Resource Stud. 2019;9(2):163. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Wang Q, Ren Q, Lao X, Zhu P. Study on Spatial-temporal differentiation of health human resources in Guangxi. Health Econ Res. 2021;38(2):62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niu A, Li P, Duan P, Ding L, Xu S, Yang Y, et al. Professional quality of life in nurses on the frontline against COVID-19. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2022;30(5):1115–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu J, Fang W, Pu H, Wang L, Ke L, Xue D. Analysis on medical staffs’ compensation structure of secondary public hospitals in one district in Shang-hai. Chin Hosp Manage. 2016;36(2):25–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M, Liu Y, Xu W, Ding D, Shan L, Guo M, et al. Comparative analysis of salary satisfaction measurement of medical staff. Chin Hosp Manage. 2015;35(6):22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W. Salary satisfaction and organizational justice. Chin Manpow Resource Dev. 2004;1(1):27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Dai T. Public hospital reforms in China: the perspective of hospital directors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Yang S, Du X, Liu Y. Salary satisfaction survey of nurses in tertiary public hospitals in China. Chin Health Qual Manage. 2022;29(8):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song W, Jiao M, Liu Y, Shi W, Huang Z, Wei W, et al. Pay satisfaction of medical staff in public hospitals: a cross-sectional study in G Province. Chin Hosp. 2021;25(10):31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegrist J. Stress in the workplace: past,present and future. Whurr; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scornet E. Random forests and kernel methods. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2016;62(3):1485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogunleye A, Wang QG. XGBoost model for chronic kidney disease diagnosis. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinf. 2020;17(6):2131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Hu D. Comparison of SVM and LS-SVM for Regression [Internet]. Vol. 1, IEEE Xplore. 2005. pp. 279–83. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/1614615.

- 16.Zhang C, Liu Y. The salary of physicians in Chinese public tertiary hospitals: a National cross-sectional and follow-up study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Zhu P, Chen H, Wu W, Feng Q, Li Y, Zeng Q et al. The status and countermeasures analysis of HR and payroll reform in Guangxi county-level public hospitals of Chinese medicine. Mod Prev Med. 2018;45(23):4302-4305.

- 18.Linda G, Shirin R. Health at a glance. Select Health Indic First Nations People Living Off Reserve. 2013;82(624).

- 19.Zheng S, Wang X, Zhao R, Wu D, Jiang S, Zhang D et al. Research on pay satisfaction of medical staff under the operation mode of one hospital with multiple districts in public hospitals. Chin Hosp Manage. 2023;43(2):13-17.

- 20.Lu Y, Wang M, Hu C, Zhou Z, Huang X. Salary satisfaction degree of public hospitals’staff in Nanjing and its influencing factors. Med Soc. 2019;32(05)52-55+90.

- 21.Chen X, Hou W, Pan W, Dong X, Xie S, Xu S et al. Salary based on the post, optimize salary system of non-institution staff in the hospital. Chin Hosp. 2014;18(12):65-67.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Variable importance of satisfaction with total pay, satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution, and satisfaction with pay growth since 2017 using Logistic regression and random forest. NOTE: A represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by Logistic regression, B represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by Random forest, C represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by Logistic regression, D represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by Random forest, E represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using Logistic regression, and F represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using Random forest.

Additional file 2. Variable importance of satisfaction with total pay, satisfaction with fairness of pay distribution, and satisfaction with pay growth since 2017 using XGboost and SHL. NOTE: A represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by XGboost, B represents the variable importance for satisfaction with total pay, as determined by SHL, C represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by XGboost, D represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding the fairness of pay distribution, as determined by SHL, E represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using XGboost, and F represents the variable importance associated with satisfaction regarding pay growth since 2017, as determined using SHL.

Data Availability Statement

The distribution of the data files is restricted by the written consent of the participating investigators. Researchers who want access to the data may contact the corresponding author, who will determine whether the requested data may be made available in a form that does not violate the written consent.