Abstract

Tissue-level phase transitions are emerging as a crucial mechanism in tumour development and metastasis. This study aims to identify molecular determinants and physical conditions that control active wetting and solid-to-fluid transition of epithelial tissues. We focused on IRSp53, a protein linking plasma membranes to the cytoskeleton. Depleting IRSp53, in MCF10 DCIS.com cells, disrupts coordinated collective movement by promoting local fluctuations in cell velocity resulting in increased tissue fluidity. In dense monolayers, IRSp53 ablation allows cells to escape the physical constraint imposed by cell crowding resulting in a delayed transition toward a jammed state. In 3D spheroids, IRSp53 loss fosters active wetting of a rigid substrate, shifting spheroid behaviour to a more fluid-like state. Biophysical modelling of the spreading cells as an active polar fluid indicates that IRSp53 depletion reduces bulk viscosity and contractility in spheroids. This effect is the result of reduced supracellular tension and disrupted organization of cell-cell junctions, which lead to decreased intercellular friction and enhanced local cell rearrangements. Molecularly, IRSp53 physically and functionally interacts with the junctional protein Afadin in the regulation of tissue tensile state and active wetting in tumour spheroids. These findings identify IRSp53 and Afadin as key regulators of tissue viscosity in breast cancer tumoroid undergoing solid-to-fluid transition linked to tumour progression. They further provide the molecular basis to causally relate subcellular and cell scale processes to tissue-levels dynamics.

Introduction

Alteration of the mechanical properties of single cells and tissues, determining their architecture, composition and function, are associated with several diseases, most notably cancer1. Cancer tissues are intrinsically linked to the mechanical properties of their cellular subcomponents2,3. Tensional, compressive, adhesive, elastic and viscous properties are mostly regulated by reorganization of the actomyosin cytoskeleton, which transmits forces at tissue level by establishing cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesions.

At tissue-level, solid-to-liquid-like and active wetting phase transitions (PT) are emerging as key determinants of cell behaviour and fate4–10. For example, normal epithelial glandular organs often adopt a solid-like state at a critical density, which depends on several biophysical parameters, such as intercellular adhesion, cortical tension, single-cell motility and cell shape variance10. This PT ensures the correct development of barrier and elastic properties in normal epithelial tissues and serves as a tumour-suppressive mechanism by preventing the emergence of aberrant, fluid-like clones5,11,12. However, disruptions in cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions, alterations of traction forces, and changes in cell shape can drive a transition toward a more fluid-like state, which has been linked to aggressive forms of cancer5,11. These factors are crucial to the transition from a jammed (solid-like) to an unjammed (fluid-like) state, a process recently identified as a driver of the transition from indolent in situ ductal carcinoma (DCIS) to invasive malignancy during breast cancer5,11,12.

A process that may recapitulate some aspects of the progression of DCIS to invasive and spreading carcinoma is the transition between three-dimensional spheroidal aggregates and two-dimensional epithelial monolayers, which can be understood as an active wetting transition5,6. Active wetting of epithelial tissue cannot be explained exclusively in terms of the physics of passive fluids9. Instead, active epithelial tissue wetting dynamics has been captured by a framework based on an active polar fluid model of tissue spreading9, whereby the transition results from the competition between traction forces and contractile intercellular stresses.

Despite the advances in the physical understanding of phase transitions, the molecular players the cells use to control these processes are poorly defined.

To gain insights into this direction, we employed 3D spheroid wetting as a model system, where spheroidal cell aggregates transition into spreading monolayers that “wet” the substrate6,9,13. Analyzing the dynamics of this process is expected to shed lights into how changes in cellular viscosity, supracellular tension, and junctional integrity contribute to tumor progression and metastasis. By combining this approach with advanced imaging, biophysical measurements, and modeling, we aimed to uncover the molecular and physical conditions that drive the transformation of normal, solid-like tissues into cancerous, fluid-like states.

We hypothesized that proteins that link the plasma membranes with the underlying cytoskeleton in epithelial tissues may be key regulators in the generation and transmission of the physical forces between adjacent cells that control supracellular cohesion, guide collective motion, and are at the base of the jammed-to-unjammed and wetting transitions.

The family of proteins that contains the membrane-bending and -binding I-BAR domain has all the key structural features to perform this function14. Among these proteins, IRSp53, the founding member of this family, stands out as it regulates the dynamic interplay between the plasma membrane (PM) and the actin cytoskeleton by sensing and promoting membrane curvature through its I-BAR domain and interacting with various actin regulatory proteins14–16. Through these activities, IRSp53 promotes directional migration by inducing filopodia and lamellipodia16–18. Of note, similar structures were also reported to shape the architecture of cell-cell adhesion in mature epithelia19,20. Accordingly, IRSp53 has been shown to play a role in cell–cell adhesion, where it is enriched21–23, and to regulate the internalization and trafficking of cell–ECM adhesive receptor -integrin24. In addition, it is required for the polarized architectural organization and morphogenesis of epithelial tissues21. In these processes, IRSp53 provides a membrane curvature-sensing/deforming platform for the assembly of multi-protein complexes that control the trafficking of apical determinants and the integrity and shape of the luminal plasma membrane21. The disruption or loss of these mechanisms is characteristic of collective breast-epithelial tumour locomotion, making IRSp53 a prime candidate to be characterised in this context.

We focused our investigations on IRSp53’s function within the framework of collective cell movement, utilizing both 2D and 3D assays of MCF10 DCIS.com cells, used as models of early breast cancer development25. Our findings indicate that the depletion of IRSp53 compromises the ability of cells to move collectively in a coordinated fashion during wound healing. In monolayers that undergo a rigidity transition due to increased cell density, IRSp53 ablation allows cells to escape the physical constraint imposed by cell crowding resulting in delayed jamming transition. Using normal and tumorigenic 3D spheroids that undergo a wetting transition6,9,13, we showed that loss of IRSp53 robustly accelerates wetting rates. Biophysical modelling of this process, based on a modified active polar fluid model9 indicated that IRSp53 controls spheroid viscosity rather than cell-substrate interaction, which we verified experimentally in multiple ways. Reduction of viscosity in IRSp53 depleted cells is the result of reduced supracellular tension and perturbed mechanical and architectural organization of cell-cell junctions, which lead to decreased intercellular friction and enhanced local cell rearrangements (tissue fluidity).

At the molecular level, we investigated the IRSp53 junctional interactome21 and we uncovered a novel functional interaction between IRSp53 and the junctional protein Afadin (AFD). Afadin, which is essential for development26–28, has been previously shown to influence the mechanical properties of epithelial cells and regulate epithelial polarity, similar to IRSp5329,30. We found that Afadin forms a complex with IRSp53, and its depletion mimics the effects of IRSp53 loss in 3D spheroid wetting assays in controlling supracellular tensile state.

Together, IRSp53 and Afadin emerge as pivotal regulators of junctional organization and the viscoelastic properties of cell collectives. By controlling solid-to-fluid transitions, these molecules play a critical role in tumor progression, bridging fundamental cellular-scale processes with tissue-scale dynamics.

Results

IRSp53 removal affects DCIS collective motion

IRSp53 regulates the dynamic interplay between the PM and the actin cytoskeleton during directional migration and invasion, has a role in cell–cell and cell–ECM adhesions, and is required for the polarized architectural organization and morphogenesis of epithelial tissues14–18,31. Perturbation or loss of these mechanisms is associated with invasive breast cancer that acquires collective locomotory behavior32.

To investigate the role of IRSp53 in this context, we developed shRNA-expressing MCF10 DCIS.com cells to knock down IRSp53 in an inducible fashion (Fig. 1A). MCF10 DCIS.com cells are an oncogenic T24 H-RAS expressing human mammary epithelial cells, which can generate ductal mammary carcinoma when injected into immunocompromised mice that eventually progress to become invasive carcinoma25. These tumors recapitulate the natural history and evolution of human DCIS lesions and display a plastic EMT state, retaining epithelial markers and features, such as the expression of junctional E-cadherin, and the ability to form rigid and jammed monolayers, but also some mesenchymal traits12. Using this model, we first examined the impact of IRSp53 on directional collective migration during wound repair in confluent epithelial monolayers. IRSp53 depletion resulted in marginal effects on the initial rate of wound closure, compared to control cells (SCR) (Fig. 1B, Rate of coverage – Early Phase, Supplementary Movie S1), but significantly reduced correlation length, and directionality in single-cell trajectories, which eventually caused a delay in closing the wound at later time points (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Movie S1). However, both wound closure as well as long-range coordinated and directional motion could be restored when murine IRSp53, resistant to the shRNA, was re-expressed in IRSp53 silenced cells (Fig. 1A–B, Supplementary Movie S1). Importantly, IRSp53 loss did not affect the migration of individual cells in one-dimensional (1D) linear motility assays (Supplementary Fig. S1A, Supplementary Movie S2), indicating that IRSp53 impacts emergent properties of the cell collective.

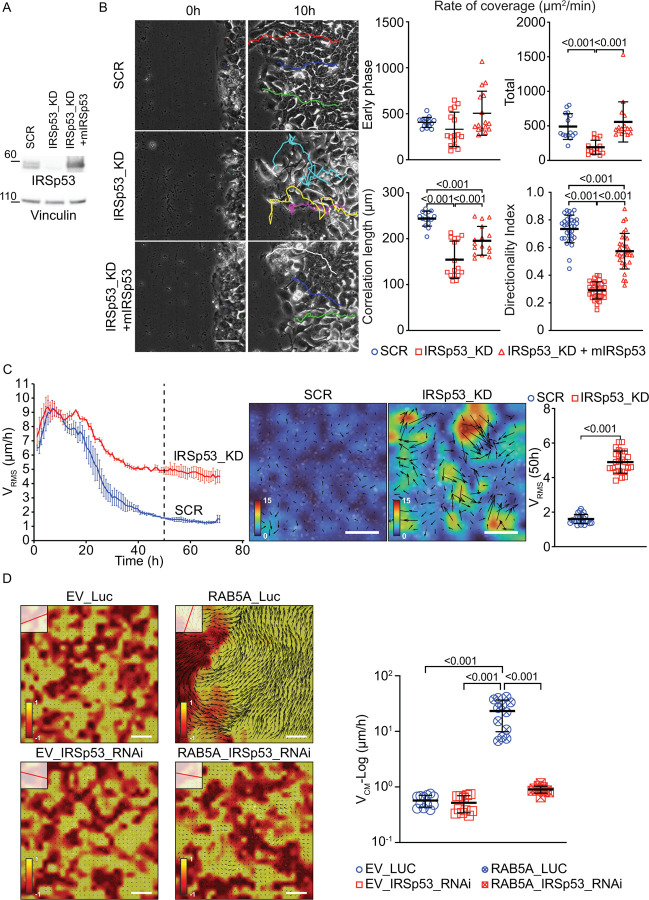

Figure 1. IRSp53 removal affects DCIS collective motion.

A. Immunoblots of doxycyclinetreated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR), IRSp53 silenced not expressing (IRSp53_KD) or expressing murine IRSp53 (IRSp53_KD + mIRSp53) with the indicated antibodies. B. Left images: scratched wound migration of doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM SCR, IRSp53_KD or IRSp53_KD + mIRSp53 monolayers (Supplementary Movie S1). Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bars, . Right, cell motility analysis. Upper graphs, the rate of coverage was quantified by measuring the percentage of area covered by cells over time (Early phase represents the 2 hours of active migration). Lower left graph, correlation length was obtained by PIV analysis. Data are mean ± SD (at least 15 fields of views were analysed from 3 independent experiments). Lower right graph, the directionality index was obtained by manually tracking single cells at the migrating front (example trajectories are shown) by ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD (n=32 cells from 3 independent experiments). C. Left, root mean square velocity over time, obtained from PIV analysis, for doxycycline-treated SCR-H2B-GFP and IRSp53_KD-H2B-mCherry MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded at jamming density and monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Movie S4). Data are mean ± SD (> 20 fields from 3 independent experiments). The vertical dashed line indicates the time point (t=50 h) corresponding to the snapshots shown beside. Centre: representative snapshots of the velocity field. The colormap reflects the magnitude of the local velocity as indicated by the colour bar. Scale bar . Right: at t=50h. Data are mean ± SD(> 20 fields from 3 independent experiments). D. Left: Representative snapshots of the velocity field (t=20h) obtained from PIV analysis of doxycycline-treated empty vector (EV) and RAB5A MCF10 DCIS.COM cells, silenced with oligos for Luciferase (EV_Luc, RAB5_Luc) or human IRSp53 (EV_IRSp53_RNAi, RAB5_IRSp53_RNAi) seeded at jamming density and monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Movie S5). The colour-map reflects the alignment with respect to the mean velocity , quantified by the parameter . A value a=1 (a=−1) indicates that the local velocity is parallel (antiparallel) to the mean direction of migration, indicated by the red line in the upper left square of each snapshot. Scale bar . Right: collective motion velocity V_CM shown in Log scale (n=12 fields from 2 independent experiments). IRSp53 and RAB5A expression was verified by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

The loss of coordination was not limited to the leading edge of migrating cells but also occurred far from the front within the monolayer (Supplementary Movie S3). This suggested that IRSp53 is crucial to enable long-range coordination of motion in epithelial monolayers. Like the parental normal mammary MCF10A cells, MCF10.DCIS.com cells form tightly packed and dense epithelial monolayers. Upon proliferation, the motion of each individual cell progressively ceases constrained by the crowding due to its neighbors. This phenomenon can be described as a fluid-to-solid (jamming) phase transition, where the cell monolayer undergoes a shift from a more fluid-like, mobile state to a solid-like, stationary, and mechanically rigid state. In this jammed state, cell motility is significantly reduced as crowding leads to physical constraints on movement10.

Notably, the silencing of IRSp53 impeded the transition to a jammed state in MCF10 DCIS.com cells. Mature IRSp53 knockdown (KD) monolayer retained a fluid-like motility, characterized by large velocity fluctuations determined by measuring the root mean square velocity (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Movie S4). Thus, IRSp53 is a critical determinant of the jamming transition in dense cell monolayer. Despite the effect on collective motility, the downregulation of IRSp53 did not affect the rate of cell proliferation deduced from plotting the time evolution of nuclear density (Supplementary Fig. S1B). This suggests that IRSp53 specifically influences physical and mechanical properties of the epithelial monolayer, rather than directly affecting cell division.

Previous research showed that the expression of the endocytic protein RAB5A is sufficient to reawaken cell motility in kinetically arrested monolayers by promoting long-range coordinated motion that results in flocking where multiple cells align their velocity vectors and local fluctuation in cell velocity that effectively fluidizes the system7,12,33. Disrupting the ability of a cell to align its locomotion with that of neighboring cells is expected to impair flocking behavior.

To explore the impact of IRSp53 on the emergence of RAB5A-induced flocking motion, we silenced IRSp53 in RAB5A-expressing MCF10.DCIS.com monolayer. As expected, RAB5A reawakened cell motility, promoting the highly coordinated motion of multicellular streams that is quantitatively captured by measuring the mean velocity of the center of mass extracted from the particle image velocimetry (PIV) analysis (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. S1C and Supplementary Movie S5). However, in the absence of IRSp53, flocking locomotion was severely compromised as indicated by a robust and significant reduction in the mean (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. S1C and Supplementary Movie S5).

Taken together, these findings highlight the critical role of IRSp53 in facilitating long-range coordinated collective motility. Specifically, IRSp53 appears essential for enabling individual cells to align their locomotion with that of their neighbors, a process fundamental for flocking behavior.

Biophysical modelling reveals that IRSp53 loss decreases tissue viscosity without impinging on cell-substrate adhesion and traction forces.

Next, we investigated what physical processes IRSp53 may regulate to control tissue dynamics and coordinated cell locomotion. We employed normal and tumorigenic 3D spheroids that undergo an active wetting transition6,9,13. These 3D spheroids transition into 2D spreading monolayers that “wet” the substrate.

Using time-lapse microscopy, we monitored the wetting dynamics of control (SCR) and IRSp53 KD spheroids on adhesive substrates. MCF10.DCIS.com spheroids, each composed of a predefined number of cells, were generated by seeding doxycycline-treated cells under low-adhesion conditions. Surprisingly, despite the loss of IRSp53 reduced directed, coordinated motion during wound healing (Fig. 1B), it significantly accelerated spheroid spreading under these conditions (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Movie S6). This observation was corroborated using primary murine mammary epithelial cells (MECs) derived from IRSp53-null mice (Supplementary Fig. S1D and Supplementary Movie S7), as well as human HaCat keratinocytes with IRSp53 downregulated via inducible shRNA (Supplementary Fig. S1E and Supplementary Movie S8).

Figure 2. IRSp53 loss decreases tissue viscosity.

A. Doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. Spheroids were then seeded on fibronectin coated 6 well plates and spreading monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Movie S6). Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bar, . Left graph, spreading area at the indicated time points was manually quantified using ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD (n=21 SCR, 20 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). Right graphs, the spreading area was also quantified with semi-automatic image segmentation with MATLAB to follow its evolution over time. The time evolution of the area for SCR and IRSp53-KD samples shows a significantly faster spreading upon IRSp53 knockdown. The solid black lines represent linear fits to the data, having a slope for SCR and for KD. The rates dA/dt quantified for single samples are shown in the boxchart. Data are mean ± SD (n=16 SCR, 11 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). B. PIV. Upper left: representative still images at t=24 h showing the spreading of a (IRSp53-KD) spheroid sample. The image on the left shows the spheroid as seen from the top with the segmentation of the spreading area outlined in red, while the frame on the right shows the corresponding local velocity field obtained from PIV analysis. The colormap represents the magnitude of the local velocity expressed in . Scale bar . A side-view schematic illustration of a spreading spheroid is reported below for a visual representation of the main geometrical parameters. The radius is the initial spheroid size, calculated as the equivalent radius of its projection at time . The radius R represents the distance of the spreading front from the center of mass and is evaluated as the equivalent radius of the spreading area. From the PIV velocity field, we calculate the azimuthally averaged radial velocity profile, and we monitor its evolution over time. The radius represents the size of the stiff core and is the point at which the radial velocity component is expected to go to zero. Right: examples of radial velocity profiles at different times for SCR and IRSp53-KD spheroids. By fitting the model to these profiles, we extract information on tissue viscosity and contractility from the fit parameters. C. Time evolution of the radius normalized by the initial spheroid size . While remains almost constant for , a fast decrease is observed upon IRSp53 knockdown, mirroring a faster melting of the ‘solid’ core. D. The melting rates calculated from linear fits of for single spheroids highlight the difference between SCR and IRSp53-KD. Data are mean ± SD (n=15 SCR, 11 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). E-F. The fit of the radial velocity profiles also gives the parameters A and B, allowing for a comparison of the ratio between the traction and the viscosity (A), as well as of the ratio between the contractility and viscosity (B). Data are mean ± SD (n=16 SCR, 11 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). G. Traction force microscopy. Upper left: representative still image showing the segmentation of a (IRSp53-KD) spheroid on the left and the corresponding traction map on the right. The colormap represents the magnitude of the local traction expressed in kPa. Scale bar . A side-view schematic illustration of a spreading spheroid is reported below for a visual representation of the main geometrical parameters. We calculate the radial traction profiles at different times and, by fitting the model to these profiles, we quantify the nematic length and the maximum traction , highlighted in the schematic illustration. Right: examples of radial traction profiles at different times for SCR (top) and IRSp53-KD (bottom) spheroids. Blue (SCR) and red (IRSp53 KD) solid lines are the best fits to the data. H. Average evolution of the maximum traction over time for SCR (blue line) and IRSp53_KD (red line). I-L. Maximum traction and average nematic length evaluated at the same spreading, when the spreading front has doubled the initial spheroid size, namely . Data are mean ± SD (n=29 SCR, 28 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). We remark that no significant difference in or is observed between SCR and IRSp53_KD.

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

Altogether, these results provide genetic evidence that IRSp53 is crucial for regulating wetting dynamics. They further indicate that IRSp53 plays a general role in controlling this process in both tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic cell assemblies.

Analogous to the behavior of liquid droplets, the propensity of cell aggregates to spread on a substrate depends on the balance between cell cohesion (cell-cell adhesion energy) and the generation of traction forces on the substrate (cell-substrate adhesion energy), which drive the expansion of the spreading sheet6,9. Since IRSp53 loss impairs wound closure dynamics (Fig. 1B), a process that shares features with the spreading of a cell sheet in 2D, it is unlikely to affect cell-substrate adhesion and sheet expansion significantly, suggesting, instead, that IRSp53 primarily regulates spheroid cell cohesion under these conditions. We investigated this further below.

In first approximation, both SCR and IRSp53_KD cells expand at a roughly constant rate . The value however dramatically changes between the two cases, the spreading of SCR spheroids being significantly lower than IRSp53_KD one (Fig. 2A). The area growth rate depends on the initial spheroid size but a significant difference between SCR and KD is observed over a wide range of spheroid sizes (Supplementary Figure S1I).

To get further insight into the spreading dynamics, we measured the time-resolved cell velocity field via PIV analysis of the phase contrast time-lapse acquisitions. The resulting radial velocity profiles, display a distinctive non-monotonic shape featuring a peak close to the boundary of the spreading monolayer (Fig. 2B), in qualitative agreement with the predictions of the model introduced earlier9.

Briefly, the model describes the cell monolayer as a two-dimensional active polar fluid, characterized in terms of a polarity field and a velocity field . In this model, the polarity field follows purely relaxational dynamics, which is assumed to be faster than the spreading dynamics. Under this adiabatic approximation, the equation for are time-independent and reads

| (1) |

where is a nematic length characterizing the persistence of planar polarity, or stated differently, it is a measure of the distance over which cell alignment persists. In the low-Reynolds number limit, the momentum conservation reduces to a force balance condition. Neglecting hydrostatic contributions, force balance requires the traction stress associated with forces exerted by substrate be equal to the gradient of the monolayer internal tension

| (2) |

where is the monolayer thickness and is symmetric part of the stress tensor. The antisymmetric part, consistently with the adiabatic approximation for the polarity field, is assumed to be negligible. The model is complemented with the following simplified constitutive equations

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

for the internal stress and the traction stress, respectively. In previous equations, represents the maximal traction stress, which quantifies the maximal force per unit area exerted by cells on the substrate; is the active stress coefficient or contractility, which is related to the active contractile forces within the tissue, driven by molecular motors like myosin; and is the monolayer viscosity, representing its resistance to flow. Remarkably, as shown before9, the model can be analytically solved in a circular geometry, assuming purely radial polarization and velocity fields. The circular monolayer (or radius ) is assumed to be fully polarized at the boundaries, leading to the boundary condition for the radial component of the polarity field, while symmetry considerations impose at the center. Similarly, the radial component of the velocity field is assumed to vanish at the center , while stress-free boundary conditions are imposed on the free edge of the monolayer.

Here, to account for the presence at the center of spreading monolayer of a persistent 3D solid aggregate, we solved the model in an annular domain of external radius and internal radius , corresponding to the size of the stiff core. Consistently, at the internal boundary, we assume and , while the conditions at the external boundary are the same as in9. More details can be found in Material and Methods section.

We used the analytical solution as a fitting model for our velocimetry data (Fig. 2B). The model accurately fits the experimental data. Fitting the solution to the data enables estimating, for each experiment and each time point, , two combinations of physical parameters, namely and , and the nematic length (Fig. 2E–F and Supplementary Fig. S1F–G) (see Material and Methods section for details).

While displays only slight differences between SCR and IRSp53 KD spheroids (Supplementary Fig. S1G, N), the temporal evolution of reveals notable disparity. Specifically, the dissolution of the solid aggregate at the center of the spreading monolayer is significantly slower in control spheroids compared to IRSp53 KD ones (Fig. 2C), as mirrored by the reduction in the normalized melting rates (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. S1O). This striking difference qualitatively accounts for the markedly reduced initial spreading rate observed in control spheroids relative to IRSp53 KD spheroids (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the primary process limiting tissue spreading in control spheroids is the fluidization and dissolution of the spheroid structure. Moreover, both and are significantly increased in IRSp53 KD aggregates (Fig 2E–F). This result, which is found to be robust across a wide range of spheroid sizes (Fig. S1L–M), indicates that the loss of IRSp53 in spreading spheroids impacts both the ratio between traction forces exerted on the substrate and viscosity, and the ratio between tissue contractility and viscosity. The ratio exhibits a reduction upon IRSp53 knockdown (Fig. S1H), which suggests an impact also on the ratio between tissue contractility and traction, independently of viscosity.

To further investigate these possibilities and dissect the parameters contributing to the parameters and , we used traction force microscopy to directly measure the traction stresses exerted by cell aggregates on the substrate during spreading (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Movie S9). We obtained radial traction profiles featuring a monotonic decay moving from the boundary of the spreading monolayer to the center (Fig. 2G), in excellent agreement with the prediction of the active polar fluid model (see Material and Methods section for details). Fitting the model to the experimental data allowed us to estimate the polar length and the maximal traction stress . Notably, no significant differences were observed in or between control and IRSp53 KD cells (Fig. 2H–L). Additionally, the estimates were consistent with values independently derived from PIV data (Supplementary Fig. S1 G, N). Our results demonstrate that traction stress remains unchanged following IRSp53 knockdown, indicating that the primary effect of IRSp53 depletion is a significant reduction in tissue viscosity and contractility.

We also monitored the size and number of focal adhesions, which have been shown to be directly dependent on the forces exerted to the substrate34. The loss of IRSp53 did not alter the number and size of focal adhesions (Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Moreover, IRSp53 was recently reported to be part of an endocytic machinery that is critical for integrin endocytosis and is involved in focal adhesion formations24. However, the loss of IRSp53 had no impact on the levels of total and active -Integrin on the cell surface, implying that IRSp53 is not, or only marginally involved in integrin trafficking in our DCIS cellular system (Supplementary Fig. S2B)

Taken together, these results indicate that IRSp53 controls the rate of spreading of epithelial spheroids by primarily regulating tissue viscosity and contractility.

Independent experimental validation of the role of IRSp53 in controlling tissue viscosity.

To experimentally validate the role of IRSp53 in the regulation of spheroid viscosity we took different approaches.

Firstly, we measured bulk rheological properties of DCIS cells in 3D aggregates by flowing spheroids into a microfluidic device. This device is composed of a channel that presents a set of consecutive constrictions of in width alternated with wider spaces (a detailed description of the system is in B.G. and G.S., manuscript in preparation). An identical number of cells is seeded in low attachment to generate spheroids of about that are pushed to enter the constricted channels by a constant pressure and flow. The passage into the first constriction is the rate-limiting step as the spheroid must undergo a sufficient deformation to enter the channel that depend on its bulk viscoelastic properties. The deformed spheroids have insufficient time to recover their shape and rapidly pass into subsequent constricted channels. The transit time across the first constriction, which is an indirect probe of the viscous component of the spheroid rheology, was reduced by about 50% in IRSp53 KD as compared to control spheroids (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Movie S10).

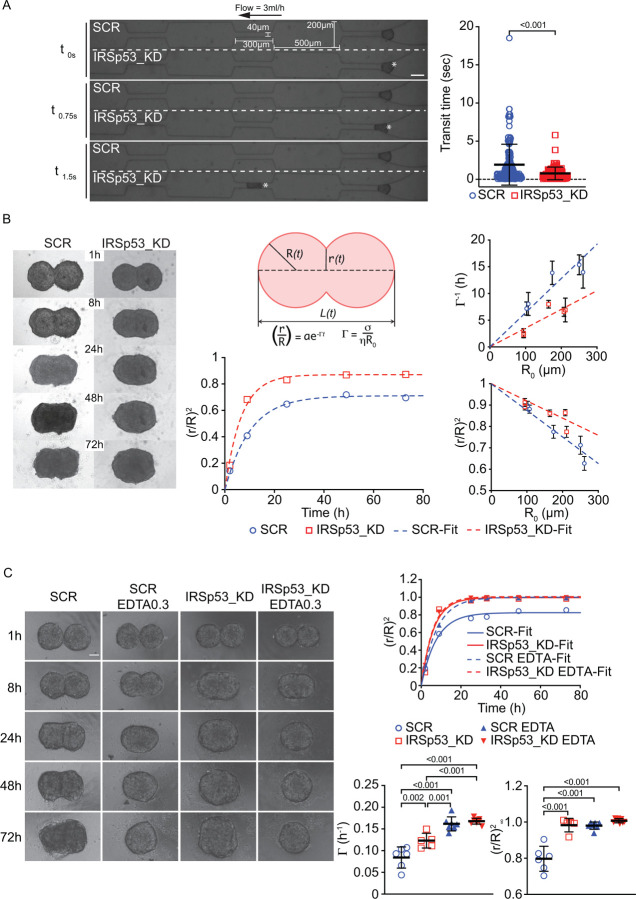

Figure 3. IRSp53 controls tissue viscosity. Validation.

A. Doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. Spheroids were then flowed into a microfluidic device designed for repetitive deformations (B.G. and G.S., manuscript in preparation). Representative still images showing a top-view of MCF10 DCIS.COM spheroids entering the first three constrictions of the deformation device (Supplementary Movie S10). Channel dimensions are shown (height ). Scale bar, . Right, transit time in the first channel was estimated by manually tracking single spheroids using ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD (n=261 SCR, 248 IRSp53_KD spheroids from 3 independent experiments). B. Left, doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids of different size (500, 2500 and 5000 cells). Pairs of spheroids of the same size were then mixed, and fusion was monitored over time. Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown (2500 cells size). Scale bar, . Centre, schematic illustration of spheroid fusion (top), indicating the main geometrical parameters like the spheroid size R and the neck radius r. Time evolution of the normalised neck radius squared (bottom) for the samples shown in the snapshots. The dashed lines are exponential fits to the data. Right, size-dependence of the fusion rate (top) and amplitude (bottom). The dashed lines represent linear fits to the data. Data are mean ± SD (n=9 SCR-500, 7 IRSp53_KD-500, 7 SCR-2500, 9 IRSp53_KD-2500, 7 SCR-5000, 8 IRSp53_KD-5000 pairs of spheroids from 2 independent experiments). C. Left, doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids in the absence or in the presence of 0.3mM EDTA (EDTA0.3) as indicated. Pairs of spheroids were then mixed, and fusion was monitored over time. Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bar, . Right, time evolution of the normalised neck radius (top) for the samples shown in the snapshots. Lines are exponential fits to the data as indicated. Bottom, Fusion rate and amplitude for the different treatments. Data are mean ± SD (n=6 SCR, 5 IRSp53_KD, 7 SCR EDTA, 8 IRSp53_KD EDTA pairs of spheroids from 2 independent experiments).

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

This finding indicates that silencing of IRSp53 results in faster spheroid deformation, consistently with a reduction in tissue viscosity and increased fluidization even in a much higher frequency regime compared to the one probed in spreading experiments.

Secondly, we conducted spheroid-fusion experiments. In these experiments, two spheroids of the same cell type and similar radius are put in contact, and their evolution over time is monitored. In close analogy with the behavior of two viscoelastic droplets, we observed a progressive fusion of the spheroids, which we monitored by considering the growth of the angle radius of the “neck” connecting the fusing spheroids (Fig. 3B). For fluid droplets, the coalescence process is driven by the surface tension of the fluid, which tends to minimize the interfacial area, and it is slowed down by the viscosity , which hinders fluid flow. The initial fusion rate for two droplets of radius is 35 (Fig. 3B). The presence of a non-negligible elastic component in the fluid rheology can prevent the complete fusion into a single spherical droplet. In general, the aspect ratio of the final aggregate is expected to be an increasing function of both the ratio between elastic modulus and surface tension and the initial radius of the coalescing droplets36.

For both control and IRSp53-devoid spheroids, the fusion rate , obtained by fitting a simple exponential function to the normalized variable , displayed a linear scaling with the inverse of the spheroid radius, as expected based on a viscoelastic droplet model. The amplitude term is expected to be for complete fusion, while for arrested coalescence . A linear fitting of enabled estimating the ratio between effective surface tension and viscosity for both IRSp53 KD and control spheroids . Notably, IRSp53-devoid spheroids fused faster (Fig. 3B), leading to significant increase (roughly by a factor of two) of the estimated ratio between surface tension and viscosity. Moreover, while small spheroids fused almost completely , for the largest spheroids, we observed arrested coalescence, the deviation of the final configuration from a single sphere being stronger for control spheroids compared to IRSp53 KD spheroids of the same size (Fig. 3B).

Importantly, treating spheroids with EDTA, which sequesters ions crucial for preserving the integrity of cell-cell junctions37—whose disruption leads to a decrease in tissue viscosity38,39—resulted in a fusion rate increase of the spheroids comparable to that observed with the loss of IRSp53 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, EDTA-treated spheroids displayed complete coalescence , while this is not the case for control spheroids (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the treatment also reduces bulk elasticity. Notably, the combined loss of IRSp53 and EDTA treatment further increased the fusion rate and led to the complete fusion of the spheroids. These findings support the idea that the loss of IRSp53 changes the biophysical properties of spheroids by decreasing viscosity and promoting tissue fluidization.

IRSp53 links individual cell mechanics to overall tissue tension to control wetting transition

In addition to decreased viscosity and increased fluidification, IRSp53 may also impact the effective surface tension of cell aggregates. This analysis is essential for distinguishing the various factors that contribute to the observed increased fusion rate in IRSp53 knockdown spheroids.

The effective surface tension of a cell aggregate represents the ratio between the energetic cost of a deformation leading to a change in the surface area (cell-matrix contact area) and the area change itself. Within the framework of the differential adhesion hypothesis (DAH), is determined by the cell-cell adhesion energy per unit area ,40

| (5) |

Physically, this equality relays on the simplifying assumption that the cortical tension in portions of the cell membrane corresponding to cell-cell contacts does not significantly differ from the cortical tension associated with cell-matrix contacts40.

We obtained direct evidence that IRSp53 significantly impacts the surface tension of cell aggregates employing demixing experiments of cells in 3D spheroids composed of genetically different cells. When SCR control and IRSp53-deficient MCF10.DCIS.com cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and allowed to form spheroids, IRSp53-deficient cells preferentially migrated to the outer layer, while SCR cells remained in the core (Fig. 4A). According to the DAH, cells forming aggregates with lower surface tension—due to weaker intercellular adhesion—tend to localize at the periphery of a tissue, whereas cells with stronger adhesion remain in the core41,42. The observed sorting pattern clearly indicates that IRSp53-deficient cells differ in their cell adhesion.

Figure 4. IRSp53 links individual cell mechanics to overall tissue tension to control wetting transition.

A. Spheroids sorting. MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) expressing GEP-E-Cad or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) expressing mCherry-LifeAct not treated (−Doxy) or treated (+Doxy) cells were mixed 1:1 and cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. 48h after seeding, live spheroids were visualized with EVOS cell imaging system. Left, representative bright fields and fluorescent images are shown. Scale bars, . Right graph, analysis of the GFP/mCherry signal area ratio, as a proxy of the cell sorting, was performed on mixed spheroids derived from control (SCR) expressing GFP-H2B or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) expressing mCherry-H2B cells spheroids (not shown), by determining fluorescent area contour with ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD (n=27 −Doxy, 26 +Doxy mixed spheroids from 3 independent experiments). B. Mechanical probing of weakly adherent single cells by AFM. Left, schematic representation of a nonadherent cell being slightly deformed by a tipless AFM cantilever. When deforming the spherical cell, changes in laser location in the photodetector are acquired and transformed to deflection in length units. F is the applied normal force, d is the cantilever deflection, Z is the piezo movement, is the cantilever spring constant, R is the initial cell radius, and h is the cortical actin thickness44. Right, cortical actomyosin tension of doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells extracted at a Z-piezo distance no greater than 1000nm. Data are mean ±SD (n=36 cells from 3 independent experiments). C. Left, schematic representation of a weakly adherent spheroids being slightly deformed by a tipless AFM cantilever. When deforming the apical cell, changes in laser location in the photodetector are acquired and transformed to deflection in length units. F is the applied normal force, d is the cantilever deflection, Z is the piezo movement, is the cantilever spring constant and R is the initial cell radius44. Right, cortical actomyosin tension of doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells in the context of 500 cells spheroids extracted at a Z-piezo distance no greater than 1000nm. Data are mean ±SD (n=48 SCR, n=42 IRSp53_KD cells from 3 independent experiments). D. Left, cortical actomyosin tension of doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells in the context of 500 cells spheroids, treated with DMSO or Blebbistatin, extracted at a Z-piezo distance no greater than 1000nm. Data are mean ±SD (n=16 SCR, n=24 SCR+Blebb, n=16 IRSp53_KD, n=24 IRSp53_KD+Blebb cells from 3 independent experiments). Right, cortical actomyosin tension of doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells in the context of 500 cells spheroids, treated with vehicle or CN03, extracted at a Z-piezo distance no greater than 1000nm. Data are mean ±SD (n=20 SCR, n=35 SCR+CN03, n=20 IRSp53_KD, n=35 IRSp53_KD+ CN03 cells from 3 independent experiments). E. Left, Doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. 6h before seeding for spreading, spheroids were added with DMSO (CTR) or Blebbistatin. Spheroids were then seeded on fibronectin coated 6 well plates and spreading monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Movie S11). Left, Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown on the left. Scale bar, . Right, spreading parameters obtained from image segmentation and PIV analysis: rate of spreading dA/dt, normalised rate of core melting d(R1/R0)/dt, ratio between traction and viscosity, A and B. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (dA/dt: n=15 SCR, 15 SCR-Bleb, 21 IRSp53_KD, 18 IRSp53_KD-Bleb spheroids; d(R1/R0)/dt, A and B: n=11 SCR, 13 SCR-Bleb, 20 IRSp53_KD, 18 IRSp53_KD-Bleb spheroids. F. Left, doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. 6h before seeding for spreading, spheroids were added with vehicle (CTR) or CN03. Spheroids were then seeded on fibronectin coated 6 well plates and spreading monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary movie S12). Representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bar, . Right, spreading parameters obtained from image segmentation and PIV analysis. From top to bottom: rate of spreading dA/dt, normalised rate of core melting d(R1/R0)/dt, ratio between traction and viscosity, ratio between contractility and traction. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (dA/dt: n=11 SCR, 19 SCR-CN03, 10 IRSp53_KD, 16 IRSp53_KD-CN03 spheroids; d(R1/R0)/dt: n=6 SCR, 11 SCR-CN03, 8 IRSp53_KD, 16 IRSp53_KD-CN03 spheroids; A and B: n=8 SCR, 16 SCR-CN03, 10 IRSp53_KD, 16 IRSp53_KD-CN03 spheroids.

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

Tissue mechanical properties are intrinsically linked to the mechanical behavior and state of individual cells2,43. Therefore, the global changes observed upon IRSp53 loss likely reflect its role in modulating individual cell mechanics14–16,31. Consequently, we investigated the impact of IRSp53 on cortical tension in both isolated cells and within large 3D aggregates using various approaches.

One approach involved atomic force microscopy (AFM) using a tipless cantilever44 to measure cortical tension in poorly adherent MCF10 DCIS.com single cells. The tipless cantilever allows for precise measurement of cell mechanical properties without piercing the cell membrane, focusing on the cortical tension as a key indicator of mechanical changes44. We found that IRSp53 loss reduced cell cortical tension by 50% (Fig. 4B). Similar results were also obtained by probing with the tipless cantilever individual cells in the context of 3D-spheroids (Fig. 4C). To confirm that the loss of IRSp53 affects cortical tension via actomyosin contractility, we tested cells under conditions where contractility was pharmacologically perturbed. Inhibition of actomyosin contractility with Blebbistatin resulted in a similar reduction in cortical tension as observed with IRSp53 knockdown, suggesting that both conditions disrupt tension in comparable ways (Fig. 4D). Conversely, promoting actomyosin contractility through RhoA activation with CN03 rescued the cortical tension defects in IRSp53-deficient cells, restoring their mechanical properties (Fig. 4D).

These findings demonstrate that IRSp53 modulates actomyosin-mediated cell tension, a critical factor in wetting transition dynamics alongside tissue viscosity, as predicted by our biophysical model. Actomyosin contractility is essential not only for regulating cell tension but also for maintaining global cell cohesion during wetting in IRSp53-depleted cells. This is evidenced by spheroid spreading rates, where Blebbistatin accelerated spreading and CN03 reduced it (Fig. 4E–F, Supplementary Fig. S2C–F and Supplementary Movies S11–12).

The cortical actin network is tightly coupled to the plasma membrane and plays a crucial role in maintaining membrane tension45,46, such that changes in cortical tension are often reflected at the membrane level. Thus, we next measured membrane tension to explore how cortical tension reduction might extend to the plasma membrane. We use FLIM microscopy with the Flipper-TR reporter47 that allows to visualize and measure changes in plasma membrane tension in real time48. We observed that IRSp53 ablation led to a significant reduction in membrane tension, both in sparsely distributed cell clusters and in confluent monolayers (Fig. 5A), further supporting its role in regulating both cortical and membrane mechanics.

Figure 5.

A. Live confocal FLIM analysis of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded to obtain sparse cell clusters or at jamming density. 72h after seeding cells were added with Flipper-TR fluorescent membrane tension probe and analysed by confocal microscopy. Left, representative FLIM images with the corresponding calibration bars representing LUT of average Flipper-TR fluorescence lifetime expressed in nanoseconds (nsec). Scale bar, . Right graphs, quantification of in vivo changes in membrane tension of cells clusters or confluent monolayers respectively. Data are mean ± SD (n=23 SCR, 20 IRSp53_KD cells in sparse clusters and n=20 SCR, 19 IRSp53_KD cells in confluent monolayers from 2 independent experiments). B. IRSp53 removal reduces cell blebbing after detachment. Time-lapse microscopy (5 min, time frame 10 sec) of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM detached cells 5 min after treatment with trypsin and gentle pipetting (Supplementary Movie S13). Left, representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bars, . Right, blebbing activity was analysed as cell area variation over time (area/frame) by XXX software. Data are mean ± SD (n= 18SCR, 24 IRSp53_KD cells from 2 independent experiments). C. Atomic force microscopy analysis of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded and grown to full confluency. Left, representative maps of Quantitative Imaging to collect Young’s modulus maps of regions of cells square microns in area. Scale bar, . Right, Young’s modulus quantification. Data are mean ± SD (n=62 fields from 3 independent experiments). D. Left, image sequence of GFP-CaaX-positive junctional vertices recoiling after nano-scissor laser ablation at t=0 in SCR and IRSp53_KD cells (Supplementary movie S14). Recoiling vertices were measured as a proxy of junctional tension. White dashed lines indicate starting positions of vertices; yellow dotted lines indicate expansion of vertices after laser ablation. Scale bar, . Top right graph, initial recoil was measured by the instantaneous rate of vertex separation at t=0 and computed using best fit single exponential curves. Bottom right plot, initial recoil rate. Data are the means ± SD, normalized to control. Data are the means ± SD (n=24 SCR, 30 IRSp53_KD from 2 independent experiments).

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

Cortical and membrane tension are critical parameters that govern the ability of isolated cells to form blebbing like protrusions either under confinement or when detached and left in suspension. We utilized this latter approach to monitor the blebbing capacity of detached, isolated cells49. Under such conditions, IRSp53 downregulation robustly reduced blebbing activity of single cells (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Movie S13), strengthening the notion that this protein is essential in regulating single-cell mechanical properties.

We also performed high resolution Atomic Force Microscopy nano-mechanical mapping. We observed that the loss of IRSp53 significantly reduces global apical and junctional stiffness, as measured by a drop in Young’s modulus in confluent monolayers (Fig. 5C).

The reduced intercellular and apical stiffness suggests that also junctional tension may be reduced following the loss of IRSp53. We tested this directly by measuring the rate of vertex recoiling after two-photon laser mediated junctional nano-scission. The instantaneous recoil from the cut site indicated that IRSp53 ablation decreased local junctional tension compared to control cells (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Movie S14).

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that IRSp53 coordinates global tissue tension by regulating the mechanical properties of individual cells, thereby controlling the wetting transition in multicellular spheroids.

IRSp53 regulates viscosity and surface tension by controlling cell junction architecture and interfacial junctional tension

How does IRSp53 control spheroid viscosity and tension? The viscosity of a cell aggregate depends on both intracellular interactions and the mechanical properties of individual cells. Intercellular tension arises from the balance of forces generated by cellular adhesion, the cytoskeleton, and intracellular contractility. It is further influenced by the structural architectural organization of cell-cell junction that directly impinges on the ability to transmit long-range forces and generate interfacial cell tension. We tested how IRSp53 impacts these properties using several orthogonal approaches.

Firstly, we perform Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) analysis of cell aggregates stably expressing GFP-E-Cadherin to visualize cell junctions. This analysis revealed that loss of IRSp53 resulted in the formation of architecturally aberrant cell-cell junctions (Fig. 6A). Two recent studies showed that epithelial adherens junctions in monolayers are not entirely flat but appear to contain interdigitated actin-rich microspikes that contribute to cell–cell adhesion19,20. Similarly, we detected extended interdigitations in control MFC10 DCIS.com spheroids, which instead were nearly absent in 3D cell aggregates devoid of IRSp53 (Fig. 6A). FIB-SEM tomographic reconstruction further confirmed the altered interdigitated structures at cell junction of IRSp53 KD spheroids (Supplementary Movies S15–16).

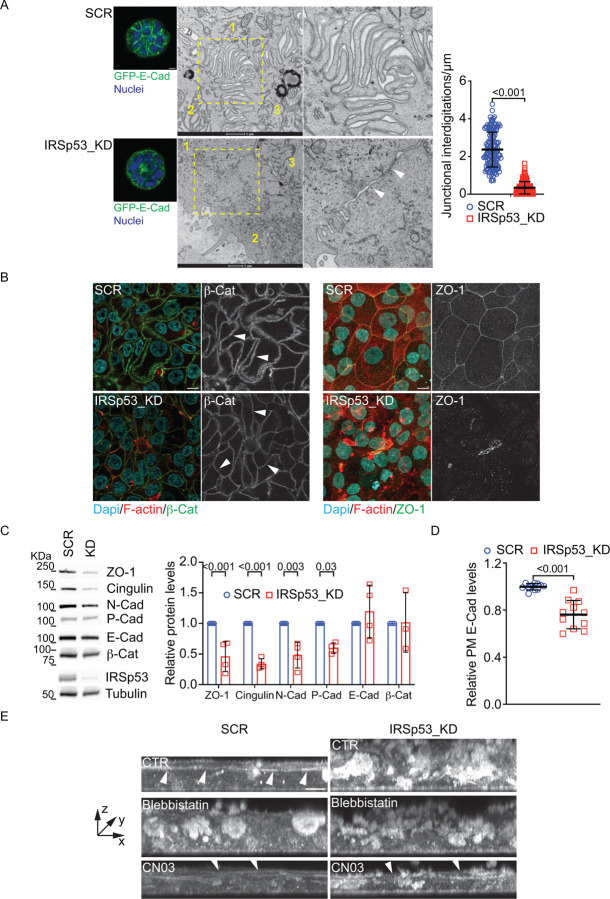

Figure 6. IRSp53 regulates viscosity and surface tension by controlling cell junction architecture.

A. Left, doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells expressing GFP-E-Cad were seeded as single cells on Matrigel-coated gridded coverslips and cultured in medium containing 2% Matrigel. The deriving spheroids were stained with NucBlue™ Live ReadyProbes ™ (nuclei, blue) and identified on grids by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, . Samples were then processed for electron microscopy and images of the corresponding spheroids are shown. Numbers indicate singles cells within the spheroids. Right panels represent 2x magnification of the area depicted by the white dashed squares. Arrowheads indicate the loss of plasma membrane interdigitations at cell-cell junction in IRSp53_KD samples. Right, quantification of junctional interdigitation/. Data are mean ± SD (n=152 fields/4 spheroids CTR, 204 fields/4 spheroids IRSp53_KD from 3 independent experiments. Samples were counted from serial sections along the Z-axis. FIB-SEM tomography was performed on the same spheroids (Supplementary Movies S15–S16). B. Left, confocal microscopy image sections ( from the bottom adherent surface) of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded at jamming density and fixed 96 hours after seeding. Cells were stained with anti--catenin antibody (green), TRITC-phalloidin to detect F-actin (red), and DAPI (blue). Right, arrowheads indicate the different architecture and thinning of cell-cell junctions highlighted by -catenin staining. Scale bar, . Right, confocal microscopy analysis of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded at jamming density and fixed 96 hours after seeding. Cells were stained with anti-ZO-1 antibody (green), TRITC-phalloidin to detect F-actin (red), and DAPI (blue). Confocal section on z axis were acquired with step-size. Representative maximum projection images are shown. Right, ZO-1 staining is shown. Scale bar, . C. IRSp53 removal perturbs junctional protein levels. Doxycycline-treated SCR or IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells were seeded at jamming density and processed for WB analysis 4 days after seeding. Left, WB analysis, with the indicated antibodies, to detect junctional proteins and IRSp53 levels. Right, relative protein levels analysis (normalized on Tubulin levels) was determined with ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD (n=4 independent experiments ZO-1, Cingulin, E-Cad, P-Cad, N-Cad, 3 independent experiments -Cat). D. IRSp53 loss alters E-Cad plasma membrane levels. FACS analysis of cell surface E-cadherin (E-Cad) in control (SCR) and IRSp53-silenced (IRSp53_KD) MCF10 DCIS.COM cells. Data are represented as mean fluorescence intensity, fraction of SCR ± SD (n=11 technical replicates from n=5 independent experiments). E. Confocal reconstruction of doxycycline-treated SCR and IRSp53_KD MCF10 DCIS.COM cells seeded at jamming density and fixed 96 hours after seeding. 16h before fixation, cells were treated with DMSO (CTR), Blebbistatin or CN03. After fixation, cells were stained with anti--Catenin (not shown) or anti-ZO1 (not shown) antibodies, TRITC-phalloidin to detect F-actin, and DAPI (not shown). Confocal section on z axis were acquired with step-size and resliced on y axis using ImageJ. Maximum projections of the F-actin channels are shown. Arrowheads (SCR CTR, SCR CN03 and IRSp53_KD CN03) indicates the supracellular actin cable. Scale bar, .

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

The alterations of junctional architecture were also highlighted by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of adherens junctions, using -catenin, and tight junctions, marked by ZO-1 (Fig. 6B) staining, in MCF10 DCIS.com monolayers. Indeed, the adherens junctions were thinner in IRSp53 KD-epithelial layers, while a global reduction in ZO-1 and its drastic reduction along cell junctions indicated the absence of an organized network of tight junctions.

The altered structural organization with the loss of interdigitating intercellular contacts suggests that the strength of cell-cell adhesion might be weakened following the silencing of IRSp53. In keeping with this possibility, IRSp53 KD MCF10.DCIS.com monolayers display frequently extended and aberrantly enlarged intercellular spaces (Supplementary Fig. S3A and Supplementary Movies S17–18). Notably, the aberrant architectural organization of junctions in IRSp53 devoid cells was also accompanied by a general reduction in the overall expression of several junctional markers, including ZO-1, Cingulin, N-Cadherin and P-Cadherin (Fig. 6C) and a slight but significant reduction of cell surface E-Cadherin (Fig. 6D).

Epithelial cells after prolonged culture as 2D monolayers have been shown to spontaneously self-organized to generate the formation of dynamics dome-like structures on solid growth supports. Dome formation requires active polarized fluid transport and the establishment of tight supracellular barrier and tensile junctional structures50, which were compromised in IRSp53 silenced monolayers. Consistently, control monolayers formed dynamically expanding and contracting domes, which were instead completely absent after silencing of IRSp53 (Supplementary Fig S3B–C and Supplementary Movie S19–20).

The altered junctional architecture may also compromise the junctional tensile state and prevent the formation of supracellular tensile cytoskeletal structures. In line with this, confocal analysis of MCF10 DCIS.com monolayers revealed that IRSp53 removal impeded the formation of force transmitting actin cables that in control cells extend through cell adhesive junction across multiple cells (Fig. 6E). Notably, the formation of supracellular actin cable in IRSp53 silenced cells could be nearly completely rescued by increasing actomyosin contractility by treatment of monolayers with the RhoA-activator CN03 (Fig. 6E). Conversely, the inhibition of actomyosin contractility by addition of Blebbistatin to control monolayers disrupted the formation of a supracellular actin cable phenocopying the loss of IRSp53 (Fig. 6E).

Thus, IRSp53 controls tissue viscosity and surface tension by regulating cell junction structure and interfacial tension, reinforcing the notion that this protein is crucial in linking global tissue mechanics to the mechanical properties of individual cells.

IRSp53 interact with Afadin to control viscoelasticity.

IRSp53 is a multidomain protein that comprises: a membrane-binding BAR domain followed by an unconventional CRIB motif, which overlaps with a proline-rich region (CRIB–PR); an SH3 domain that recruits actin cytoskeleton effectors; a PDZ binding motif at the very C-Term14,15,51. We investigated the IRSp53 proximity interactome, previously generated using both canonical and quantitative SILAC proteomics combined with BirA-based proximity labeling21. This approach allowed us to identify proteins in close proximity or binding to IRSp53, providing insights into its interaction network. Many of the newly identified interactors were cell junction proteins. Through RNAi screening in a 3D spheroid spreading assay, we tested multiple candidate genes to determine which interactors of IRSp53 could mimic its loss-of-function phenotypes. Afadin (AFD) emerged as the only effective candidate. Notably, Afadin is a junctional protein essential during development in mice, Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans26–28; it has been shown to specifically influence the epithelial cortical tension29 and the epithelial polarity program as IRSp5330. This suggests that Afadin may function in a similar pathway or as a key partner in regulating cell junctions and collective cell movement, making it a critical player in maintaining tissue integrity alongside IRSp53. Consistently, Afadin ablation phenocopied IRSp53 loss during 3D-spheroids wetting (Fig. 7A, Supplementary Fig. S3D–E and Supplementary Movie S21). To confirm the IRSp53-Afadin interaction, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments and found that ectopically expressed Afadin binds to the IRSp53-SH3 mutant (W413G)16 but not the wild-type form (Fig. 7B). This suggests that the SH3 domain normally inhibits Afadin binding in the wild-type protein. IRSp53 is known to fold into a closed, inactive conformation, with the CRIB-PR region binding the SH3 domain. Activation requires cooperative interactions: Cdc42 binding to its CRIB-PR domain and effector proteins, such as Eps8, binding to the SH3 domain, open the protein and expose interaction sites51. Hence, Afadin likely interacts with the open conformation, independent of the SH3 domain. In vitro pull-down assays with purified IRSp53 fragments confirmed that Afadin binding requires the C-terminal region of IRSp53, not the SH3 domain (Fig. 7C). This reinforces that the SH3 domain regulates IRSp53’s conformation and interactions51, while Afadin associates specifically with the C-terminal region when IRSp53 is in its active, open form.

Figure 7. IRSp53 interacts with Afadin to control viscoelasticity.

A. Doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR), IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) or Afadin silenced (AFD_KD) cells were cultured in ultra-low adhesion condition to form spheroids. Spheroids were then seeded on fibronectin coated 6 well plates and spreading monitored by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Movie S21). Upper left, representative still images at the indicated time points are shown. Scale bar, . Upper right, WB analysis, with the indicated antibodies, was performed to detect IRSp53 and Afadin levels. Lower graphs, spreading parameters obtained from image segmentation and PIV analysis. From left to right: rate of spreading dA/dt, rate of core melting d(R1/R0)/dt, A and B. Data are means ± SD from 3 independent experiments (dA/dt: n=34 SCR, 37 IRSp53_KD, 36 AFD-KD spheroids; d(R1/R0)/dt: n=26 SCR, 29 IRSp53_KD, 26 AFD-KD spheroids; A and B: n=34 SCR, 31 IRSp53_KD, 33 AFD-KD spheroids). B. IRSp53 interaction with Afadin is enhanced by loss of function of the SH3 domain. Co-immunoprecipitation: lysates (4 mg) of 293T cells, transfected with the indicated constructs, were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Flag antibody. Input lysates and immunoprecipitates (IPs) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. C. Analysis of IRSp53-Afadin surface interaction. Lysates (2 mg) of 293T cells transfected with GFP-Afadin were incubated with of immobilized GST–IRSp53 fragment as indicated or GST. Lysates () and bound proteins were immunoblotted with anti-GFP antibody. Ponceau staining was employed to detect GST recombinant proteins. D. IRSp53 loss decrease cell cortical tension. Doxycycline-treated MCF10 DCIS.COM control (SCR), Afadin silenced (AFD_KD) or IRSp53 silenced (IRSp53_KD) cells were cultured as monolayers. Left, examples of terminal web laser ablation in SCR, AFD_KD and IRSp53_KD cells expressing, mCherry-CaaX (see also Supplementary Movie S22). Location of ablation is depicted by dotted orange line. The cell contour at t = 0 is represented by a full yellow line (kept on all images), and the one at later time points is represented by a dashed with line. Scale bar, . Upper right graph, quantification of the evolution of the normalized apical surface area over time after ablation in SCR, AFD_KD and IRSp53_KD cells. Geometric shapes, individual cells, dashed lines averaged over one cell type. For normalization, all cell areas are scaled to 1 at t = 0. Bottom right graph, relative value of initial area spreading measured as the relative area difference over time between t = 0 and t = 3s29. Data are mean ± SD (n=50 SCR, 36 AFD_KD, 29 IRSp53_KD cells from 2 independent experiments).

Statistical analysis for each experiment is included in the Methods section. P values are indicated in each graph.

Afadin (AFD) has been identified as critical for maintaining the epithelial cell cortical tension by regulating the apical contraction apparatus29. To investigate whether IRSp53 influences cortical tension in a similar manner, we conducted apical surface laser ablation experiments following IRSp53 depletion. The results showed that the loss of IRSp53 led to a reduction in apical tension, mimicking the effects seen with Afadin depletion (Fig. 7D, Supplementary Movie 22). This confirms that both IRSp53 and Afadin collaborate to regulate epithelial mechanics and maintain tissue integrity by controlling cortical tension. Their functional interaction at cell junctions highlights their role in shaping tissue architecture, especially in the dynamic regulation of mechanical forces across epithelial layers.

Conclusion and perspective

This study establishes IRSp53 and its functional partner Afadin as central regulators of the viscoelastic properties of epithelial tissues, providing a molecular framework for understanding the solid-to-fluid transitions essential to tumor progression. We demonstrate that IRSp53 exerts its effects by modulating junctional architecture, tensile state, and intercellular cohesion, processes that are directly linked to tissue viscosity and fluidification. The depletion of IRSp53 reduces supracellular tension and disrupts the structural organization of adherens and tight junctions, leading to decreased intercellular friction and enhanced local cell rearrangements. This drives a shift from a solid-like to a fluid-like state, evidenced by increased tissue spreading rates and spheroid fluidization in both 2D monolayers and 3D spheroids.

At the molecular level, IRSp53’s interaction with Afadin emerges as a critical mechanism underlying these transitions. Afadin, known to regulate cortical tension and epithelial polarity, collaborates with IRSp53 to maintain the integrity of cell-cell junctions and supracellular tensile structures. Together, they bridge cellular mechanics with tissue-scale dynamics, enabling the regulation of active wetting and phase transitions that underpin epithelial tissue remodeling during cancer progression. This interplay highlights how cellular-scale processes, such as junctional tension and actin cytoskeleton organization, drive emergent tissue behaviors, including viscosity modulation and collective cell motility.

The findings of this study contribute to a growing understanding of the molecular determinants of tissue mechanics in cancer biology. By revealing the critical roles of IRSp53 and Afadin in regulating tissue fluidification, this work paves the way for potential novel therapeutic strategies targeting solid-to-fluid transitions in cancer. Future studies however are necessary to explore how these molecular pathways integrate with other biophysical processes, such as extracellular matrix remodeling and immune cell infiltration, to drive tumor progression and metastasis. Furthermore, expanding the analysis of IRSp53 and Afadin functions to other tissue types and disease models could uncover broader implications for their roles in development, regeneration, and disease.

Methods

Antibodies and DNA constructs

The complete list of used antibodies and DNA constructs is reported in the “Reagents List” table.

Cell culture

MCF10 DCIS.com cell line was cultured at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM):Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) GlutaMAX medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% horse serum, 0.5mg/mL hydrocortisone, 10mg/mL insulin, and 20ng/mL EGF. HaCat cell line was cultured at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% cultured in DMEM High Glucose medium (Euroclone) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and 4mM L-Glutamine.

To treat monolayer and wetting spheroids, blebbistatin (B0560 - Sigma-Aldrich) and RhoA Activator II (CN03A – Cytoskeleton) were added hours before imaging and respectively used at the final concentration of 5mM and .

IRSp53 knock-down & over-expression

To perform IRSp53 ablation in MCF10 DCIS.com and HaCat cells, we cloned a specific shRNA against human IRSp53 into Tet-pLKO-puro plasmid (Addgene Plasmid #21915). The target sequence was identified with the online tool from Broad RNAi Consortium (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/seq/search) and is the following: CAGCAAGAATCCTCAGAAGTA. As negative control, we used a Scrambled (shSCR) sequence (GTGGACTCTTGAAAGTACTAT)52. SCR and IRSp53_KD bulk populations were obtained by lentiviral transduction and selected by puromycin (final concentration: ). To get IRSp53 depletion, we added doxycycline to the medium 48–72 hours before starting each experiment, to allow degradation of endogenous protein. Efficiency of inducible knock-down was evaluated by Western blot. To rescue IRSp53 expression, we cloned murine IRSp53 into pRRL-SIN vector and obtained stably-expressing cells by lentiviral transduction.

In the RAB5A-dependent collective motility experiments, IRSp53 down-modulation was achieved by a specific siRNA (SASI_HS01_00210743 from Sigma-Aldrich, target sequence: GGAAGAAATGCTGAAGTCT), while a Luciferase siRNA (Duplex from Dharmacon, sequence: CATTCTATCCTCTAGAGGATG) was used as negative control. siRNAs were transfected in 2 successive cycles (reverse and forward) at the final concentration of 25nM with RNAiMAX (13778150 – Thermofisher), according to manifacturer’s instructions. Efficiency of Rab5A over-expression and IRSp53 knock-down were evaluated by qPCR with the following Taqman assays: RAB5A:hs00702360_s1 and BAIAP2:Hs00170734_m1.

To perform afadin ablation in MCF10 DCIS.com, pGFP-shLenti-AFD shRNA2 construct was stably expressed by lentiviral transduction (a kind gift from Marina Mapelli Lab30).

Collective motility (wound-healing)

SCR and IRSp53_KD cells were seeded in 6-well plate (1.5*106 cells/well) in complete medium with doxycycline . The day after, monolayer was scratched with a pipette tip and carefully washed with 3X PBS to remove cells and create a cell-free wound area. The closure of the wound was monitored by time-lapse with Leica TIRF inverted microscope (widefield acquisition only) with 10X objective every 10 minutes for 24 hours, at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% .

The percentage of area covered by cells over time was calculated using a custom Fiji and MATLAB code. The area covered over time was fitted with two straight lines (https://github.com/aganse/MultiRegressLines.matlab/blob/master/regress2lines.m) and the slope of the second line was used to estimate the maximal rate of coverage, after a lag phase. On the cell layers identified, velocity fields were extracted by Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) using the Matlab mpiv toolbox (https://www.oceanwave.jp/softwares/mpiv/index.php), with an interrogation window of 60×60 um and a 25 % of overlap and a time interval of 10 minutes between two consecutives frames. The correlation length (Lcorr) was estimated fitting the normalized velocity spatial correlation function, along the radius , with an exponential function . Directionality index was obtained by manually tracking leader cells at the migrating front with Manual Tracking plugin from Fiji and analyzing obtained trajectories with Chemotaxis Tool plugin.

Unjamming-to-Jamming transition

SCR (H2B-GFP labelled) and IRSp53_KD (H2B-mCherry labelled) cells were seeded in confluent conditions (near jamming density) in 12-well plate (6*105 cells/well) in complete medium with doxycycline . The day after, transition from unjamming (fluid-like) to complete jamming (solid-like) state was monitored by time-lapse with Olympus ScanR inverted microscope with 10X objective every 10 minutes for 72 hours, at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% .

Maps of the instantaneous cellular velocities were obtained by analyzing time-lapse phase-contrast movies of cell monolayers with Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) using a custom MATLAB script. The interrogation windows were typically 64 or 128 pixels (44.9 or ) on a side, with a 50% overlap between adjacent windows. For a given monolayer, time-lapse images from 8 different fields of view were simultaneously collected.

PIV analysis quantifies speed and direction of cell flow within each interrogation window. From the velocity map, we computed the instantaneous velocity of the center of mass as the average velocity , where is the instantaneous velocity at time in the -th interrogation window and denotes the average over all the interrogation windows. The root mean square velocity was then quantified as . The time evolution of was calculated for each single field of view. Results were then averaged, at each time point, over all fields of view of the same cell type.

RAB5A-dependent collective motility

MCF10 DCIS.com H2B-labelled cells (pSLIK-EV & pSLIK-RAB5A)12,53 were subjected to 2 successive cycles of RNA interference (reverse and forward) with a specific siRNA against human IRSp53 (Luciferase siRNA was used as negative control) at the final concentration of 25nM, according to manifacturer’s instructions (RNAiMax, 13778150 – Thermofisher). Cells were seeded in 6-well plate (1.5*106 cells/well) in complete medium. After 48 hours from first RNA interference cycle (reverse), doxycycline was added to induce Rab5A expression and after additional 6 hours time-lapse was started. Collective motility was monitored by time-lapse with Olympus ScanR inverted microscope with 10X objective every 5 minutes for 24 hours, at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% . After the end of time-lapse, cells were collected for RNA extraction and analysis of RAB5A/IRSp53 expression by qPCR.

Analysis of local and collective cell motility was performed via PIV analysis of the time-lapse phase-contrast movies. The interrogation windows were 32 pixels on a side, with a 50% overlap between adjacent windows.

The instantaneous velocity of the center of mass was computed as the average velocity , where is the instantaneous velocity at time in the -th interrogation window and denotes the average over all the interrogation windows. The alignment between the local velocity and the collective velocity was quantified within each grid point via the parameter , where a value indicates that the local velocity is parallel (antiparallel) to the mean direction of migration.

1D motility

Micro-patterns of fibronectin-coated lines ( wide) were fabricated using photo-lithography54. The glass surface of the round coverslip (25 mm diameter) was activated with plasma cleaner (Harrick Plasma) and then coated with cell repellent PLL-g-PEG (Surface Solutions GmbH, 0.5mg/mL in 10 mM HEPES). After washing with PBS 1x and deionized water, the surface was illuminated with deep UV light (UVO Cleaner, Jelight) through a chromium photomask (JD-Photodata). Then, coverslips were coated with 10ug/ml fibronectin (1056 – Sigma Aldrich).

SCR and IRSp53_KD cells were seeded onto patterned coverslips 16 hours before starting the time-lapse (1*104 cells in 2 ml of complete medium with doxycycline ). Linear motility along patterns was monitored with Olympus ScanR inverted microscope with 10X objective every 10 minutes for 24 hours, at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% . To perform cell segmentation and tracking, a specific software in C++ with the OpenCV [http://opencv.willowgarage.com/wiki/] and the GSL [http://www.gnu.org/software/gsl/] libraries was developed. The analysis of cell migration was performed by the C++ software coupled with R [www.R-project.org]55.

Spheroid formation & wetting

In the majority of wetting experiments, SCR and IRSp53_KD spheroids (from MCF10 DCIS.com and HaCat cells) were obtained by seeding 5*103 cells in 200 ul of complete medium with doxycycline in 96-well Clear Round Bottom Ultra-Low Attachment Microplate (7007 – Corning) and centrifuging them for 5 minutes at 1200 rpm, to allow the gathering of cells at central area of each well. After 16 hours, compact roundish spheroids are formed (one for each well). In specific experiments, spheroids of different sizes were obtained by seeding 2.5*102, 1*103 or 5*103 cells according to the protocol described above.

For wetting time-lapse experiments, 6–12 spheroids for each experimental condition were collected, pooled and seeded on fibronectin-coated (final concentration: ) 6-well plate (one well for each condition). Spheroids were incubated for 1 hour at 37’C to allow their attachment, then spreading was monitored with Olympus ScanR or iXplore inverted microscope with 4X objective every 10 minutes for 48 hours (MCF10 DCIS.com) or every 20 minutes for 72 hours (Hacat), at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% .

The contact area between the cell aggregates and the substrate was calculated at fixed time points (8 h, 16 h, 24 h) with Fiji. Its evolution over time was obtained via automatic segmentation of the time-lapse phase-contrast movies with custom MATLAB scripts. Only frames where the contact area had exceeded the initial spheroid projection of at least 20% were considered. The early stage spreading rate of each spheroid was then estimated by fitting the experimental curves with a linear fit of the kind over the first 24 hours. The initial spheroid size was estimated from the spheroid projected area in the first frame of the time-lapse acquisition as the equivalent radius .

Time-resolved cell velocity field was obtained via PIV analysis of time-lapse phase-contrast movies of spreading spheroids. PIV analysis was performed after masking the image portion outside the contact area to screen the background and calculate the velocity field only within the spreading monolayer. The same mask, obtained from contact area segmentation, was used for consecutive frames. The time interval between consecutive frames was 5 or 10 min and the interrogation windows were 8 or 16 pixels (26.1 or ) on a side.

The radial velocity component in each grid point was computed by considering the scalar product where is the unit vector pointing from the centroid of the contact area to the center of the -th interrogation window. We then computed the radial velocity profiles at a given time , by performing an azimuthal average over the grid points at the same distance from the centroid.

The radial velocity profiles were first averaged over 5 consecutive frames and then fitted with the analytical solution of obtained from the model, which has the following form:

where is the nematic length, is the position at which the radial velocity vanishes (representing the size of the solid core), is the position of the spreading front, and is the modified Bessel function of the first kind and -th order.

The analytical solution was fitted only up to the radial position corresponding to 1.07% , where is the position of the maximum of the experimental velocity profile, to reduce artefacts coming from boundary jags. For the fit to converge, was fixed to the boundary value, while , and were kept as free fit parameters.

Mammary Epithelial Cells purification & spheroid formation