Abstract

Objective

The STEPPER (Status Epilepticus in Emilia‐Romagna) study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches of status epilepticus (SE) in adults of the Emilia‐Romagna region (ERR), Northern Italy.

Methods

STEPPER, an observational, prospective, multicentric cohort study, was conducted across neurology units, emergency departments, and intensive care units of the ERR over 24 months (October 2019–October 2021), encompassing incident cases of SE. Patients were followed up for 30 days.

Results

A total of 578 cases were recruited (56% female, mean age = 70 years, 32% with previous diagnosis of epilepsy, 43% with in‐hospital onset, 35% stuporous/comatose, 46% with nonconvulsive SE). Etiology was known in 87% (acute 43%, remote 24%, progressive 17%, definite epileptic syndrome 3%). The mean pre‐SE Rankin Scale score was 2, the Status Epilepticus Severity Score was ≥4 in 33%, the Epidemiology‐Based Mortality Score in Status Epilepticus score was ≥64 in 61%, and 34% were refractory. The sequence of treatments followed current clinical practice guidelines in 63%. Benzodiazepines (BDZs) were underused as first‐line therapy (71%), especially in in‐hospital onset cases; 15% were treated with continuous intravenous anesthetic drugs. Mortality was 24%; 63% of survivors had functional worsening. At the two‐step multivariable analysis, incorrect versus correct treatment sequence with correct BDZ dose was the strongest predictor of failure to resolve SE in the in‐hospital group (odds ratio [OR] = 4.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.86–10.5), with a similar trend in the out‐of‐hospital group (OR = 2.22, 95% CI = .98–5.02). In turn, failure to resolve was the strongest predictor of 30‐day mortality (OR = 11.3, 95% CI = 4.16–30.9, out‐of‐hospital SE; OR = 6.42, 95% CI = 2.79–14.8, in‐hospital SE) and functional worsening (OR = 5.83, 95% CI = 2.05–16.6, out‐of‐hospital SE; OR = 9.30, 95% CI 2.22–32.3, in‐hospital SE).

Significance

The STEPPER study offers insights into real‐world SE management, highlighting its significant morbidity and functional decline implications. Although nonmodifiable clinical factors contribute to SE severity, modifiable factors such as optimized first‐line therapies and adherence to guidelines can potentially influence prognosis.

Keywords: antiseizure medications, cohort studies, EEG, natural history studies, status epilepticus

Key points

SE is confirmed as a condition with high mortality and morbidity, with a 30‐day mortality rate of 24% in our study population.

The in‐hospital SE onset subgroup showed a poorer prognosis in terms of mortality compared to the out‐of‐hospital population.

In our population, incorrect treatment sequence is the major prognostic factor for failure to resolve SE, which in turn has the greatest impact on mortality.

Modifiable factors such as optimized first‐line treatments and adherence to guidelines can potentially impact the prognosis of SE.

1. INTRODUCTION

Status epilepticus (SE) is a neurological emergency characterized by prolonged seizure activity, with a significant risk of morbidity and mortality, that has not significantly decreased in the past decades. 1 Although the urgency of prompt recognition and treatment is well established, SE is a complex condition with various clinical presentations and underlying causes. Of these, convulsive SE (CSE) represents the most severe presentation and demands immediate intervention to reduce adverse outcomes. Nevertheless, the diverse etiologies, symptomatology, duration, and context of SE contribute to a wide range of prognoses, making tailored and swift management essential for positive patient outcomes. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Historically, the definition of SE has evolved, with progressive shortening of timelines to emphasize the importance of early intervention. Although evidence supports the efficacy of treatments during the earlier stages, 9 refractory SE (RSE) and superrefractory SE remain areas with limited available evidence, presenting challenges for clinicians seeking to optimize patient care.

Current treatment algorithms propose a three‐stage approach, with benzodiazepines (BDZs) as first‐line agents, intravenous antiseizure medications (ASMs) as a second line, and continuous intravenous anesthetic drugs (CIVADs) as a third line. However, approximately 30% of cases progress to RSE, 10 requiring the infusion of anesthetic agents in an intensive care setting to terminate seizures.

Despite guidelines in place, there is evidence of underdosing of BDZs and lack of adherence to treatment escalation protocols, highlighting the importance of further research and improvement in clinical practice. 11 , 12 Moreover, most current guidelines focus on CSE treatment, whereas indications on other forms of SE constitute a “gray area” where the risk–benefit ratio of each action is challenging to assess.

Over the past two decades, epidemiological and prognostic investigations focused on SE have been conducted in the northern Italian region of Emilia‐Romagna. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 Throughout this timeframe, the 30‐day case fatality rates largely varied between a minimum of 5% and a maximum of 50%. 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 20 Such differences may be, at least in part, related to different treatment approaches as suggested by a study conducted in this region. 8

Furthermore, evidence suggests that the patient location at SE onset is a significant prognostic predictor, 6 , 7 , 8 with higher mortality in in‐hospital (IH) de novo SE, presumably due to a different selection of other prognostic factors, 7 but possibly also to different treatment approaches.

The STEPPER (Status Epilepticus in Emilia‐Romagna) study was conducted in the Emilia‐Romagna region (ERR) over 2 years to shed light on this critical medical condition. The study aimed to comprehensively investigate the clinical characteristics and management strategies of SE, with a specific focus on administered therapies, adherence to guidelines, and prognostic factors, according to patient's location at SE onset (out‐of‐hospital [OH] and IH).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The STEPPER study is an observational, prospective, and multicentric cohort study. The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed. 21

2.1. Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Area Vasta Emilia Centro of the ERR (CE‐AVEC: 18036). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients/guardians of participants in the study. In the absence of a legally authorized representative, the ethics committee granted a waiver for consent if the patient's clinical condition did not allow him/her to provide it.

2.2. Setting and study population

The study was conducted in all neurology units, emergency departments, and intensive care units (ICUs) serving the adult population of the ERR (3 741 002 residents). The study included incident cases of SE in adult patients over 24 months (October 2019–October 2021). The study adopted the definitions and classification provided by the International League Against Epilepsy. 9

2.3. Procedures

A designated neurologist acted as the reference neurologist for each neurology unit, responsible for proactive surveillance of the eligible patients in neurological wards, neurological consultations, electroencephalographic (EEG) recording, and interaction with the related emergency departments and ICUs. Data collection was facilitated through a dedicated website and a centralized electronic database (electronic clinical record form [eCRF]) accessed with personal usernames and passwords. Each eCRF was identified with a unique number corresponding to an individual patient, allowing for anonymous data treatment.

The enrolled patients underwent a follow‐up assessment 30 days after SE onset.

2.4. Variables

The collected clinical data included demographic characteristics (age, gender, residence, ethnicity, weight, height); date of admission to the observation unit; SE onset date and time; history of seizures, other SE episodes, or epilepsy prior to SE; where applicable, ongoing ASM therapy, its dosage (pre‐SE), and withdrawal date and time; OH/IH onset; ongoing neuroprotection pre‐SE; modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score pre‐SE; SE etiology and classification; prognostic scores (Epidemiology‐Based Mortality Score in Status Epilepticus [EMSE], Status Epilepticus Severity Score [STESS]); diagnostic procedures at onset (date and time of the first neurological consultation and the first EEG; time of any lumbar puncture, acute brain computed tomography [CT] scan, perfusion CT scan, brain magnetic resonance imaging, or other neuroimaging; body temperature; blood tests); pharmacological treatment of SE (type of medication; loading dose; date, time, and route of administration); IH complications; and date and destination of discharge.

Among all the pharmacological treatments administered to the patients, only the BDZs and ASMs administered with a loading dose and the anesthetics that after the loading dose were subsequently provided in continuous infusion were considered as the acute drug treatment of SE.

We assessed the appropriateness of drug treatment and its adherence to clinical practice guidelines (CPG) 22 by focusing on three aspects:

Order of administration. We considered as according to CPG only the administration of BDZs as the first line, ASMs as the second line, and CIVADs as the third line. Oral administration was considered appropriate only for drugs that cannot be administered intravenously (for example, perampanel). A maximum of two doses of the same or two different BDZs was considered appropriate. For CSE, we considered correct a maximum of two attempts with intravenous ASMs. For the other types of SE, more than two attempts with ASMs were considered appropriate if the proper sequence of administration was respected; escalation to CIVADs was not considered mandatory for the appropriateness of the treatment.

Dosing. This analysis was limited to BDZs, because the patient's weight was often missing; therefore, we were not able to determine whether ASM and CIVAD doses were appropriate in most patients. Because only adult patients were included, we considered that most of them weighed >32 kg; therefore, doses of at least 10 mg of midazolam and diazepam and 4 mg of lorazepam were considered correct. 12 , 23 , 24 , 25

Route of administration. We considered appropriate the intravenous administration of BDZs, ASMs, and anesthetics and the intramuscular or buccal administration of midazolam when used as first‐line treatment as well as rectal administration of diazepam.

Based on these assumptions, we classified the possible therapeutic combinations administered to patients into six patterns: correct sequence with correct BDZs dose; correct sequence with underdosed BDZs; correct sequence without CIVADs; incorrect sequence without CIVADs; correct sequence with CIVADs; and incorrect sequence with CIVADs.

The following outcomes were evaluated during the follow‐up period: SE resolution at discharge; “functional worsening,” defined as an increase of at least 1 point on the mRS scale at the last follow‐up compared with the pre‐SE mRS score; and 30‐day mortality. 26

2.5. Statistical plan and analysis

In the descriptive analysis, the cohort's characteristics were presented as mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency for categorical variables.

All the subsequent analyses were stratified for IH and OH SE onset. We decided to consider IH and OH onset SE separately because previous studies have shown that the prognosis of IH onset SE is worse, as it is associated with nonmodifiable variables such as age and comorbidities. 6 , 7 , 8 Moreover, the care pathways and professionals the patients encounter could be different between the two settings.

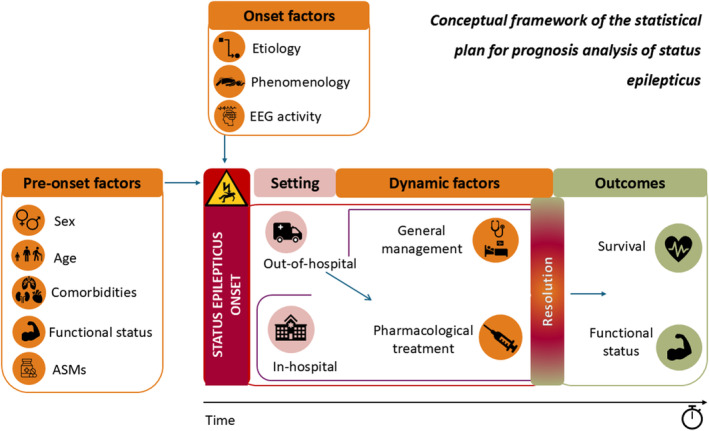

Then, we conceptualized prognostic factors according to the following categories (Figure 1): pre‐onset factors (sex, age, mRS score pre‐SE, comorbidities assessed by the comorbidity subsection of the EMSE, ASMs), onset factors (SE etiology and classification, state of consciousness, EEG), and first‐level (general management, appropriateness of pharmacological treatment) and second‐level (failure to resolve) dynamic factors.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of the statistical plan for prognosis analysis of status epilepticus (SE). Prognostic factors are categorized as pre‐onset factors (sex, age, comorbidities assessed by the comorbidity subsection of the Epidemiology‐Based Mortality Score in Status Epilepticus scale, modified Rankin Scale score pre‐SE [functional status], antiseizure medications [ASMs]), onset factors (SE etiology, SE classification [phenomenology], electroencephalographic [EEG] activity), first‐level dynamic factors (general management, pharmacological treatment), and second‐level dynamic factors (resolution). Prognostic outcomes are failure to resolve (intermediate outcome), functional worsening (according to modified Rankin Scale score), and survival at 30 days.

The chi‐squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to evaluate the univariable association between outcomes (SE resolution, functional worsening, and 30‐day mortality) and categorical or continuous variables, respectively. Three different multilevel mixed‐effect logistic regression models were implemented to describe the prognosis after SE corresponding to the three outcomes. The center of recruitment was considered a cluster variable in all multivariable regressions. In the first stratified model, we evaluated the association between SE failure to resolve (dependent variable) and the baseline factors (sex, EMSE comorbidity), the SE factors (SE etiology and classification, state of consciousness), and the first‐level dynamic factor (appropriateness of drug treatment). In the second and third stratified models, we evaluated the association between 30‐day mortality and functional worsening (dependent variables) and the baseline factors (age, mRS pre‐SE, EMSE comorbidity), the SE factors (SE etiology and classification, state of consciousness), and the second‐level dynamic factor (SE failure to resolve). The results are presented as odds ratio (OR) and the relative 95% confidence interval (CI).

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 14.2.

3. RESULTS

We recruited 610 patients, of whom 32 postanoxic SE cases were excluded from the analysis because of the well‐known poor prognosis of this condition; therefore, the whole cohort includes 578 patients. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort and the two main subpopulations, the IH and the OH onset subgroups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics between the two groups: in‐hospital and out‐of‐hospital onset.

| Characteristic | Total cohort, N = 578 | Out‐of‐hospital onset, n = 329 | In‐hospital onset, n = 249 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex—female, n (%) | 322 (55.7) | 172 (52.3) | 150 (60.2) | .056 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 70.4 (16.6) | 68.8 (17.4) | 72.6 (15.2) | .019 |

| Center, n (%) | .016 | |||

| Bologna | 148 (25.6) | 73 (22.2) | 75 (30.1) | |

| Modena | 170 (29.4) | 102 (31.0) | 68 (27.3) | |

| Reggio Emilia | 17 (2.9) | 13 (4.0) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Parma | 67 (11.6) | 39 (11.9) | 28 (11.2) | |

| Ferrara | 54 (9.3) | 23 (7.0) | 31 (12.5) | |

| Piacenza | 27 (4.7) | 15 (4.6) | 12 (4.8) | |

| Romagna | 95 (16.4) | 64 (19.5) | 31 (12.5) | |

| mRS pre‐SE, median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–3) | 3 (1–4) | .012 |

| mRS post‐SE, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–4) | 4 (3–5) | <.001 |

| STESS score ≥ 4, n (%) | 187 (33.3) | 79 (24.9) | 108 (44.3) | <.001 |

| 17 missing | 12 missing | 5 missing | ||

| Consciousness, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Alert/somnolent | 360 (65.0) | 231 (73.6) | 129 (53.8) | |

| Stuporous/comatose | 194 (35.0) | 83 (26.4) | 111 (46.2) | |

| 24 missing | 15 missing | 9 missing | ||

| EMSE total score ≥ 64, n (%) | 332 (61.1) | 161 (53.0) | 171 (71.6) | <.001 |

| 35 missing | 25 missing | 10 missing | ||

| EMSE comorbidity score ≥ 60, n (%) | 50 (8.7) | 29 (8.8) | 21 (8.4) | .872 |

| SE classification, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Prominent motor symptoms—other | 225 (38.9) | 114 (34.7) | 111 (44.6) | |

| Prominent motor symptoms—convulsive | 86 (14.9) | 58 (17.6) | 28 (11.2) | |

| Nonconvulsive with coma | 79 (13.7) | 26 (7.9) | 53 (21.3) | |

| Nonconvulsive without coma | 188 (32.5) | 131 (39.8) | 57 (22.9) | |

| Etiology, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Acute | 248 (42.9) | 90 (27.4) | 158 (63.5) | |

| Progressive | 100 (17.3) | 74 (22.5) | 26 (10.4) | |

| Remote | 136 (23.5) | 97 (29.5) | 39 (15.7) | |

| SE in defined epileptic syndrome | 17 (3.0) | 14 (4.2) | 3 (1.2) | |

| Unknown | 77 (13.3) | 54 (16.4) | 23 (9.2) | |

| Intensive care unit admission—yes, n (%) | 114 (22.3) | 48 (17.3) | 66 (28.2) | .003 |

| 66 missing | 51 missing | 15 missing | ||

| Refractoriness—yes, n (%) | 201 (34.8) | 90 (27.4) | 111 (44.6) | <.001 |

| Use of third‐line treatment [denominator is refractoriness—yes], n (%) | 91 (46.4) | 34 (39.1) | 57 (52.3) | .065 |

| Reason for not using third‐line treatment, n (%) | .020 | |||

| “Benign” SE | 28 (27.5) | 20 (38.5) | 8 (16.0) | |

| Severe clinical conditions | 66 (64.7) | 27 (51.9) | 39 (78.0) | |

| Other | 8 (7.8) | 5 (9.6) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Epilepsy—yes, n (%) | 187 (32.4) | 131 (39.8) | 56 (22.6) | <.001 |

| Failure to resolve SE, n (%) | 95 (16.4) | 44 (13.4) | 51 (20.5) | .022 |

| Mortality 30 days after SE, n (%) | 140 (24.4) | 51 (15.6) | 89 (35.9) | <.001 |

| 3 missing | 2 missing | 1 missing | ||

| Functional worsening [1‐point worsening on mRS], n (%) | 355 (63.4) | 166 (52.5) | 189 (77.5) | <.001 |

| 18 missing | 13 missing | 5 missing |

Abbreviations: EMSE, Epidemiology‐Based Mortality Score in Status Epilepticus; IQR, interquartile range; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; SE, status epilepticus; STESS, Status Epilepticus Severity Score.

3.1. Demographic data

Of the 578 patients, 322 (56%) were females, the mean age was 70 years, the median pre‐SE mRS was 2 (IQR = 0–4), and 32.4% had a previous diagnosis of epilepsy.

3.2. Phenomenology, etiology, STESS, and EMSE

Approximately one third (35%) of the patients had a level of consciousness that qualified as stuporous or comatose. SE with prominent motor symptoms accounted for 54% of cases (15% CSE). Nonconvulsive SE (NCSE) cases comprised 46%: 14% with coma and 32% without coma. Forty‐three percent of the patients had IH onset.

Among the 501 patients with a known etiology, this was acute in 43%, progressive in 17%, and remote in 24%; only 3% of patients presented with SE in a definite epilepsy syndrome. Among the acute causes, cerebrovascular (38%) was the most frequent one, followed by sepsis/fever (23%), metabolic (10%), and central nervous system infection (encephalitis/meningitis, 10%). In 6% of the patients, the supposed etiology was the discontinuation of ASMs/BDZs, and in 2.5% it was toxic substances intake. An autoimmune etiology was present in 2.5% of the cases. Within the progressive etiologies, brain tumors accounted for 79% of the cases and dementia for 14%. Prior stroke accounted for 61% of the remote etiologies, followed by posttraumatic (12%).

STESS score was 4–6 in 33% of patients, whereas 61% had an EMSE score > 64.

The IH and OH subgroups significantly differed in the following variables: age, mRS pre‐SE, STESS, consciousness EMSE, SE semiology, SE etiology, and previous diagnosis of epilepsy (see Table 1).

3.3. Diagnostic procedures

EEG, brain CT scan and blood tests at onset were performed in most patients (93%, 89%, and 84%, respectively). A perfusion CT scan was performed in 9% of the population (52/578) and 13% of the NCSE cases, after a median of 3 h (range = .58–6.8) from onset.

For the 147 patients for whom the timing (time to SE onset) could be calculated, the first EEG was obtained after a median of 6 h after onset (3.25 h in NCSE).

3.4. Therapy

The patients received a median of three treatments (range = 1–13); 20% received one treatment, 35% two treatments, and 43% three or more.

Only 27% of cases (156 patients) reported the exact time of SE onset and of the first treatment administration; among these patients, the median interval between onset and first treatment was 1.05 h (IQR = .25–2.8).

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of SE treatments in terms of frequency and combinations.

TABLE 2.

Status epilepticus drug treatment in the STEPPER cohort with details according to type of drugs, benzodiazepine use, and correct or incorrect sequence.

| Type of drug | Specific treatment/all treatments, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 643/1728 (37) |

| Diazepam | 328/643 (51) |

| Lorazepam | 206/643 (32) |

| Midazolam | 109/643 (17) |

| Antiseizure medication | 931/1728 (54) |

| Levetiracetam | 324/931 (35) |

| Lacosamide | 258/931 (28) |

| Valproate | 173/931 (19) |

| Phenytoin | 119/931 (13) |

| Perampanel | 26/931 (3) |

| Anesthetics | 154/1728 (9) |

| Propofol | 88/154 (57) |

| Midazolam | 38/154 (25) |

| Ketamine | 22/154 (14) |

| Thiopental | 6/154 (4) |

| Benzodiazepine use | Patients treated with BDZ/patients treated, n (%) a | Patients correctly treated with BDZ/patients treated with BDZ, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All cohort | 404/567 (71) | 298/404 (74) |

| By administrator | ||

| Emergency medical services (ambulance) | 69/73 (95) | 35/69 (51) |

| Neurologist | 257/401 (64) | 204/257 (79) |

| Emergency department doctor | 43/44 (98) | 35/43 (81) |

| Anesthesiologist | 2/12 (17) | 2/2 (100) |

| Other | 35/37 (95) | 11/35 (31) |

| By setting | ||

| In‐hospital onset | 148/247 (60) | 111/148 (75) |

| Out‐of‐hospital onset | 256/320 (80) | 187/286 (73) |

| Drug treatment sequence | Patients with correct sequence/patients treated, n (%) a | Patients with incorrect sequence/patients treated, n (%) a |

|---|---|---|

| All cohort | 356/567 (63) | 211/567 (37) |

| Correct BDZ dose | 264/567 (46) | |

| Underdosed BDZ | 92/567 (16) | |

| With CIVADs | 31/567 (6) | 57/567 (10) |

| Without CIVADs | 325/567 (57) | 155/567 (27) |

Abbreviations: BDZ, benzodiazepine; CIVAD, continuous intravenous anesthetic drug; STEPPER, Status Epilepticus in Emilia‐Romagna.

Eleven patients not treated or data missing.

Considering all the medications that were administered to the patients, the class of medications most often used were ASMs (54%), followed by BDZs (37%) and CIVADs (9%; Table 2).

The most frequently administered BDZ was diazepam (51%). Levetiracetam was the most used ASM (35%), followed by lacosamide (28%) and valproate (19%). Among CIVADs, propofol was used in 57%, midazolam in 25%, ketamine in 14%, and thiopentone in 4% of the patients who received a third‐line therapy.

3.5. First‐line treatment

The first drug administered to treat SE was a BDZ in 71% of cases, of which 74% were at the correct dose (Table 2). The propensity to employ BDZs as the first treatment and use them at the correct dosage varied according to the prescriber and the assistance setting. When emergency medical services (EMS) administered the first treatment, it consisted of a BDZ in 95% of cases, but in only 51% of cases the dose was correct. Neurologists prescribed BDZs first in 64% of cases, of which 79% were correctly dosed. The emergency doctors used BDZs first in 98% of cases, and in 81% of them, they were at a correct dose. Moreover, IH onset cases were treated first with a BDZ less often than patients with OH onset (60% vs. 80%, respectively).

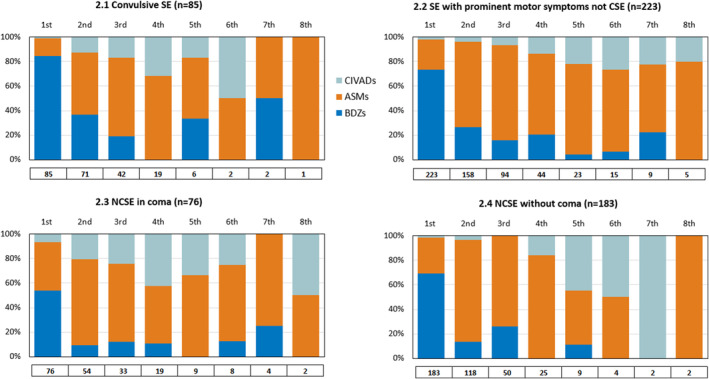

ASMs are the most common second pharmacological attempt (70%), but almost one quarter of patients received a BDZ (22%) and a minority a CIVAD (7.4%). At each further attempt until the sixth, the use of ASMs, BDZs, and anesthetics varied between 71%–60%, 18%–7%, and 9.5%–30% of cases, respectively. We subsequently divided the study population into four subgroups according to semiology: CSE, SE with prominent motor symptoms non‐CSE, NCSE in coma, and NCSE without coma. The four groups did not differ substantially regarding drug class used at each pharmacological attempt (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Pharmacological treatment of status epilepticus (SE) in the four groups: convulsive SE (CSE), SE with prominent motor symptoms not CSE, nonconvulsive SE (NCSE) in coma, NCSE without coma. Each bar represents the percentage of patients receiving each drug class (antiseizure medications [ASMs]/benzodiazepines [BDZs]/continuous intravenous anesthetic drugs [CIVADs]) at each therapeutic attempt, from the first to the last in temporal order. The total number of patients treated at each therapeutic attempt is indicated below the bars.

3.6. Combinations of treatments

The correct sequence of treatments was administered in 63% of cases, of which 74% received the correct dose of BDZ (Table 2). Patients treated with CIVADs comprised 15.5% (88 patients); in 65% of these cases (57 patients), an incorrect treatment sequence was used. SE was considered RSE in 34% of cases, of which only 45% received CIVADs. The reason anesthetics were not used was explicitly asked; considering the benefits and risks associated with the use of CIVADs and orotracheal intubation, the referring physician chose a less aggressive strategy in most cases (60%) because the SE was considered a “benign condition,” but in 30% of cases because the patient's condition was considered “too severe”.

3.7. Outcomes at follow‐up

SE eventually resolved in 84% of cases after a median interval from onset of 2.8 h (the onset and resolution times were specifically reported in only 22% of cases).

Mortality at 30‐day follow‐up was 24% in the whole population, 37% in the subgroup of NCSE with coma, and 38% in RSE. Among the survivors, 63% had a functional worsening at follow‐up, with a median post‐SE mRS of 3.

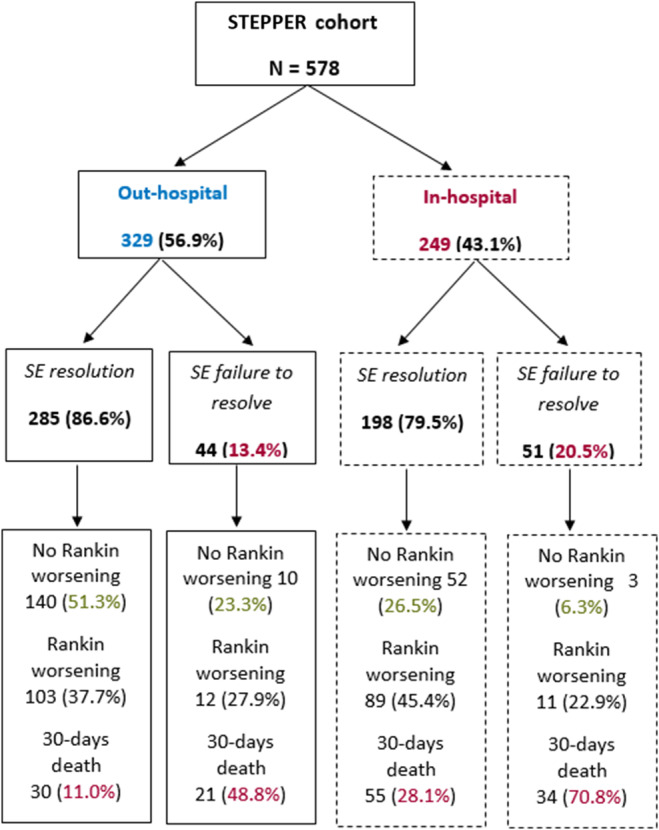

Figure 3 and Table 1 show the proportion of patients for each outcome in each of the two subpopulations. IH onset patients had a worse prognosis, as 30‐day mortality, failure to resolve, and functional deterioration were significantly higher compared to the OH group. However, 30‐day mortality was higher in those SE cases that failed to resolve (48.8% in the OH group and 70.8% in the IH group).

FIGURE 3.

Status epilepticus (SE) outcome is shown in the two groups: in‐hospital and out‐of‐hospital onset.

Table S1 in supplementary material shows the associations between the possible prognostic variables and each of the three outcomes according to the univariable analysis in the two subpopulations.

According to the multivariable analysis (Table 3), in the OH group, the failure to resolve was associated with stupor/coma (OR = 2.75, 95% CI = 1.08–6.98) and, as a trend, with the use of an incorrect sequence of treatment (OR = 2.22, 95% CI = .98–5.03), female sex, and EMSE comorbidity score ≥ 60. In the IH group, the failure to resolve was associated with an incorrect sequence of treatment (OR = 4.42, 95% CI = 1.86–10.5) and inversely associated with NCSE without coma.

TABLE 3.

Variables associated with the three different outcomes at multivariable analysis: failure to resolve, mRS worsening, and 30‐day mortality.

| Independent variable | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: failure to resolve | Out‐of‐hospital onset, n = 329 | In‐hospital onset, n = 249 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female vs. male | 2.16 (.99–4.73) | .054 | .64 (.30–1.37) | .251 |

| EMSE comorbidity score | ||||

| ≥60 vs. <60 | 2.61 (.87–7.86) | .088 | 2.40 (.73–7.91) | .149 |

| Consciousness | ||||

| Stuporous/comatose vs. alert/somnolent | 2.75 (1.08–6.98) | .033 | 1.07 (.48–2.41) | .862 |

| SE classification [vs. prominent motor symptoms—other] | ||||

| Prominent motor symptoms—convulsive | 1.72 (.56–5.26) | .339 | .96 (.31–3.01) | .948 |

| Nonconvulsive with coma | .57 (.13–2.63) | .474 | .90 (.31–2.59) | .842 |

| Nonconvulsive without coma | 1.32 (.51–3.38) | .564 | .31 (.10–.94) | .039 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Acute vs. other | .95 (.37–2.42) | .907 | .78 (.33–1.87) | .579 |

| Progressive vs. other | 1.71 (.71–4.13) | .233 | 1.21 (.32–4.57) | .780 |

| SE treatment sequence | ||||

| Incorrect vs. correct with correct BDZ dose | 2.22 (.98–5.02) | .057 | 4.42 (1.86–10.5) | .001 |

| Correct with underdosed BDZ vs. correct with correct BDZ dose | .90 (.32–2.53) | .847 | 2.17 (.66–7.13) | .202 |

| Outcome: mRS worsening | Out‐of‐hospital onset, n = 316 | In‐hospital onset, n = 244 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Years | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <.001 | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | .002 |

| mRS pre‐SE | ||||

| 3 vs. 0–2 | 1.33 (.59–2.98) | .490 | .30 (.11–.83) | .020 |

| 4–5 vs. 0–2 | .61 (.29–1.29) | .197 | .12 (.05–.29) | <.001 |

| EMSE comorbidity score | ||||

| ≥60 vs. <60 | 1.35 (.45–4.01) | .589 | 6.01 (.70–51.3) | .101 |

| Consciousness | ||||

| Stuporous/comatose vs. alert/somnolent | 1.56 (.67–3.61) | .300 | 3.00 (1.22–7.40) | .017 |

| SE classification [vs. prominent motor symptoms—other] | ||||

| Prominent motor symptoms—convulsive | .31 (.11–.85) | .023 | 3.06 (.70–13.3) | .137 |

| Nonconvulsive with coma | 1.39 (.30–6.47) | .672 | 1.17 (.39–3.54) | .779 |

| Nonconvulsive without coma | 1.12 (.57–2.21) | .742 | 1.44 (.56–3.70) | .445 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Acute vs. other | 2.27 (1.15–4.48) | .010 | 1.51 (.68–3.37) | .308 |

| Progressive vs. other | 6.79 (3.02–15.3) | <.001 | 1.02 (.24–4.32) | .981 |

| Failure to resolve vs. resolution of SE | 5.83 (2.05–16.6) | .001 | 9.30 (2.34–36.9) | .002 |

| Outcome: 30‐day mortality | Out‐of‐hospital onset, n = 327 | In‐hospital onset, n = 248 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Years | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | .001 | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <.001 |

| EMSE comorbidity score | ||||

| ≥60 vs. <60 | 1.34 (.39–4.60) | .637 | 6.03 (1.76–20.7) | .004 |

| Consciousness | ||||

| Stuporous/comatose vs. alert/somnolent | 1.89 (1.28–6.47) | .204 | 2.29 (1.09–4.83) | .029 |

| SE classification [vs. prominent motor symptoms—other] | ||||

| Prominent motor symptoms—convulsive | 1.38 (.42–4.57) | .600 | 1.43 (.49–4.12) | .511 |

| Nonconvulsive with coma | 2.23 (.60–8.36) | .233 | 1.22 (.47–3.14) | .686 |

| Nonconvulsive without coma | .70 (.26–1.89) | .485 | 1.66 (.70–3.90) | .248 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Acute vs. other | 1.12 (.42–4.57) | .600 | 1.12 (.53–2.37) | .763 |

| Progressive vs. other | 3.46 (1.35–8.87) | .010 | .22 (.05–.99) | .048 |

| Failure to resolve vs. resolution of SE | 11.3 (4.16–30.9) | <.001 | 6.42 (2.79–14.8) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BDZ, benzodiazepine; CI, confidence interval; EMSE, Epidemiology‐Based Mortality Score in Status Epilepticus; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; OR, odds ratio; SE, status epilepticus.

The following variables were associated with 30‐day functional worsening (Table 3) in the multivariable analysis: age and failure to resolve (OR = 5.83, 95% CI = 2.05–16.6, OH group; OR = 9.30, 95% CI = 2.34–36.9, IH group), in both the subgroups; mRS pre‐SE and stupor/coma, only in the IH group; and CSE and acute and progressive etiologies, only in the OH subgroup.

Finally, age, progressive etiology and failure to resolve (OR = 11.3, 95% CI = 4.16–30.9, OH group; OR = 6.42, 95% CI = 2.79–14.8, IH group) were independently associated with 30‐day mortality (Table 3) in both the IH and OH subgroups, whereas a comorbidity score ≥ 60 and stupor/coma significantly impacted on mortality only in the IH subgroup.

4. DISCUSSION

This is a real‐life observational study conducted on a large cohort of adult patients prospectively enrolled at 17 centers in the ERR. We found that incorrect treatment sequence is the major prognostic factor of failure to resolve SE in patients with IH onset and shows a similar trend in patients with OH onset. Failure to resolve is, in turn, the major prognostic factor of 30‐day mortality and 30‐day poor functional status (according to mRS) in both subgroups.

Regarding treatment choices, we compared our results with the studies conducted in the ERR in the early 2000s. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 The predilection for diazepam among BDZs has remained unchanged, even though studies have decreed that nonintravenous midazolam should be the drug of choice in the prehospital phase 27 , 28 and that intravenous lorazepam might be better than intravenous diazepam. 29 Conversely, the use of levetiracetam (35%) has increased, becoming the most prescribed ASM, displacing phenytoin (13%), which was the most widely used in the previous studies. 13 , 14 , 15 The common use of levetiracetam and lacosamide (28%) is presumably the result of choices based on safety profiles, real or perceived, and of the characteristics of our study population (advanced age, various comorbidities), in which drugs with few interactions are preferred. The preferential use of levetiracetam could also be explained by the predominant cerebrovascular etiology in our cohort (38%) and is in line with the same trend of use in poststroke epilepsy in Italy. 30

Regarding CIVADs, our data align with the “European” trend highlighted in the 2019 international audit to prefer propofol to midazolam. 31 Despite the growing evidence of its potential in treating SE, we have observed limited use of ketamine. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35

We confirm a high 30‐day mortality rate of 24% in our study population, which aligns with previous studies conducted in our geographic area but surpasses rates reported in more recent research. Several characteristics of our population, including advanced age, high prevalence of comorbidities, unfavorable etiologies, and elevated EMSE score, may partially account for the relatively poor prognosis observed, given that they are known unmodifiable risk factors for mortality. Consistently, we found higher mortality in the IH subgroup, which showed statistically significant differences from the OH population precisely in those unmodifiable characteristics: age, mRS pre‐SE, STESS, EMSE, SE semeiology, and SE etiology. This finding echoes a recent study by Brigo et al. 7 that observed a poorer prognosis in terms of mortality and functional outcome in the IH population, which was attributed to the presence of unfavorable clinical factors.

It is important to acknowledge that deviations from treatment CPG may also have contributed to the negative prognosis observed in our patients. Our study provides evidence that certain treatment approaches, such as incorrect treatment sequencing and underdosing of BDZs, may play an independent role in increasing the risk of SE persistence, at least in the IH subgroup. Persistence of SE, in turn, emerged as an independent risk factor for mortality and functional worsening at follow‐up in both subgroups.

Concerning the misuse of BDZs, Kellinghaus et al. found likewise that the initial administration of a BDZ versus a non‐BDZ ASM predicts earlier SE cessation. 36 Our study reveals a notable trend: the probability of BDZ use as the first line of treatment is higher when administered outside the hospital by EMS personnel. However, they are less likely to use BDZs at the correct dosage. Conversely, IH onset cases are less frequently treated with BDZs, especially when managed by neurologists, who typically adhere to proper dosage guidelines. The underdosing of BDZs, a phenomenon observed in prior studies 12 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 and known to increase the risk of RSE, 40 may be in part explained by the higher perceived risk of drug‐induced respiratory failure using “high” doses of BDZs, especially in patients with comorbidities or severe general conditions. 41 This concern might have also applied to the IH cases in our cohort.

Although there is evidence of suboptimal utilization of BDZs as a first‐line therapy, there is a counterintuitive trend toward their repeated use in subsequent lines of treatment, extending well beyond the second therapeutic attempt, irrespective of whether SE presents with prominent motor symptoms. Such misuse of BDZs has previously been linked to poorer outcomes, including a higher risk of intubation, ICU admission, and respiratory depression/insufficiency. 11

Regarding deviations from guidelines in general, we initially expected that they would have been less frequent in cases of CSE than in NCSE. This assumption was based on the guidelines allowing more discretion to clinicians, especially concerning the use of CIVADs, in cases of RSE. Surprisingly, our study found similar clinician behavior across different subtypes of SE, with inadequate utilization of CIVADs even in cases of CSE. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of correct medication management, emphasizing that deviations from treatment guidelines can significantly impact clinical outcomes. For instance, De Stefano et al. observed a decrease in the likelihood of returning to premorbid function with each additional nonanesthetic antiseizure drug administered before anesthesia. 42 A prospective comparison of 57 adults with SE in the ERR disclosed that correct medical management (i.e., correct type, dosage, and sequence of the drugs administered) versus incorrect treatment was strongly and independently related to clinical outcome (OR = 21.09). 8 However, the effect of adherence to treatment guidelines on mortality and functional prognosis remains debated. Whereas some studies suggest a significant impact, others find it to be less influential. For instance, a prospective study conducted on 225 incident cases of SE observed at a single center by Rossetti et al. found that better application of SE treatment guidelines has an insignificant prognostic effect on mortality and functional prognosis of SE. Yet, the authors suggest that further research is necessary to understand the implications of incorrect medication sequencing on SE prognosis. 43 Finally, a recent systematic review on outcomes of deviation from treatment guidelines in SE, including 22 studies published between 1970 and 2018, revealed that nonadherence to SE management guidelines was associated with an increased chance of worse outcomes, including ICU admission and mortality. 11

One limitation of our study is that, despite being a prospective study, data related to the onset of SE, the timing of treatment administration, and the correct dosage were frequently missing or not detectable, given the intrinsic difficulty of identifying this condition, particularly in cases of NCSE. Consequently, our analysis focused solely on the correctness of drug sequencing and route of administration, without considering dosage and timing in relation to SE onset. On the other hand, this may suggest that applying the correct treatment sequence impacts prognosis even when the exact duration of SE is unknown, as frequently happens in clinical practice, where NCSE onset is often not definable. Another limitation, theoretically intrinsic in this kind of prognostic study and probable in a complex condition such as SE, is the presence of unmeasured confounding factors associated with outcomes (e.g., genetic factors, health organization influences).

In conclusion, our study shows that improved use of first‐line therapies and greater adherence to treatment guidelines are associated with a higher likelihood of resolution of SE and, consequently, lower mortality. SE remains a condition burdened by high morbidity and functional worsening in survivors. Although undoubtedly nonmodifiable factors such as etiology, comorbidities, and age, to name a few, certainly play a role in determining the severity of this situation, our case analysis reveals that there are potentially modifiable factors that can influence its course. Further studies are needed to confirm the impact of treatment strategies on SE prognosis.

Enhancing SE management by emphasizing both organizational and educational aspects for health care personnel involved in its treatment may foster adherence to treatment guidelines, ensuring timely and proper interventions. This, in turn, has the potential to ameliorate the prognosis associated with this condition, which remains one of the main emergencies in the neurological field. Further studies are needed to refine our understanding of modifiable factors in SE management.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content: Lidia Di Vito, Eleonora Matteo, Stefano Meletti, Corrado Zenesini, Luca Vignatelli, Paolo Tinuper, and Francesca Bisulli. Major role in the acquisition of data: Lidia Di Vito, Eleonora Matteo, Stefano Meletti, Giorgia Bernabè, Chiara Bomprezzi, Maria Chiara Casadio, Carlo Alberto Castioni, Edward Cesnik, Carlo Coniglio, Marco Currò‐Dossi, Patrizia De Massis, Elisa Fallica, Irene Florindo, Giada Giovannini, Maria Guarino, Elena Marchesi, Andrea Marudi, Elena Merli, Giulia Monti, Niccolò Orlandi, Elena Pasini, Daniela Passarelli, Rita Rinaldi, Romana Rizzi, Michele Romoli, Mario Santangelo, Valentina Tontini, Giulia Turchi, Mirco Volpini, Andrea Zini, Lucia Zinno, Roberto Michelucci, Paolo Tinuper, and Francesca Bisulli. Study concept or design: Stefano Meletti, Roberto Michelucci, Luca Vignatelli, Paolo Tinuper, and Francesca Bisulli. Analysis or interpretation of data: Lidia Di Vito, Eleonora Matteo, Corrado Zenesini, and Luca Vignatelli.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was part of a larger project (STEPPER [Status Epilepticus in Emilia‐Romagna]) funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (bando 2016 Ricerca finalizzata ordinaria RF‐2016‐02361365) after undergoing a peer‐reviewed grant award process. The funding body had no role in the design of this study or during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results. The publication of this article was supported by the "Ricerca Corrente" funding from the Italian Ministry of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

F.B. has received grants or contracts from the Italian Ministry of Health; has received consulting fees from Eisai, Angelini, UCB, and Takeda; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from LivaNova; and has been a member of the Lafora advocacy group executive board. E.C. has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eisai and Angelini Pharma. L.D.V. has received grants or contracts from the Italian Ministry of Health and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Angelini. I.F. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Angelini; and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Angelini. S.M. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from UCB Pharma, Eisai, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Angelini; and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from UCB Pharma, Eisai, Angelini, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. R.M. has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Angelini and Eisai. N.O. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Eisai. M.R. has participated on the steering committee of the FibER trial. A.Z. has received consulting fees from Boehringer‐Ingelheim, CSL Behring, and Angels Initiative; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, and Angels Initiative; has received payment for expert testimony (Alexion–AstraZeneca); and has participated on a data safety monitoring or advisory board for Bayer and AstraZeneca. L.V. has received grants or contracts from the Italian Ministry of Health. None of the other authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

DATA S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roberto D'Alessandro and Marco Zanello, former professors at the University of Bologna, Italy, for their help in writing the STEPPER study protocol.

Di Vito L, Matteo E, Meletti S, Zenesini C, Bernabè G, Bomprezzi C, et al. Prognostic factors and impact of management strategies for status epilepticus: The STEPPER study in the Emilia‐Romagna region, Italy. Epilepsia. 2025;66:753–767. 10.1111/epi.18227

STEPPER study group: IRCCS Istituto Delle Scienze Neurologiche di Bologna, Bologna, Italy: Emanuele Saverio Cece, Fabio Nobili, Gabriele Ricci, Gloria Stoffella, Maria Tappatà, Stefania Testoni, Anna Zaniboni. University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy: Roberto D'Alessandro, Marco Zanello. Ospedale Maurizio Bufalini, Cesena, Italy: Yerma Bartolini, Giovanni Bini. Department of Neuroscience and Rehabilitation, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy: Maura Pugliatti. Rimini “Infermi” Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Rimini, Italy: Francesca Ceccaroni, Chiara Leta. University Hospital of Parma, Parma, Italy: Claudia Giorgi, Edoardo Picetti. Ospedale Ramazzini of Carpi, AUSL Modena, Carpi, Italy: Alessandro Pignatti. SSD Neurologia Ospedale Santa Maria Della Scaletta, Imola, Italy: Ilaria Naldi. Neurology Unit, Department of Neuro‐Motor Diseases, AUSL—IRCCS of Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy: Marco Russo. Santa Maria Delle Croci Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Ravenna, Italy: Federico Domenico Baccarini, Anna Rita Guidi.

Contributor Information

Luca Vignatelli, Email: l.vignatelli@ausl.bologna.it.

the STEPPER study group:

Emanuele Saverio Cece, Fabio Nobili, Gabriele Ricci, Gloria Stoffella, Maria Tappatà, Stefania Testoni, Anna Zaniboni, Roberto D’Alessandro, Marco Zanello, Yerma Bartolini, Giovanni Bini, Maura Pugliatti, Francesca Ceccaroni, Chiara Leta, Claudia Giorgi, Edoardo Picetti, Alessandro Pignatti, Ilaria Naldi, Marco Russo, and Anna Rita Guidi

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Neligan A, Noyce AJ, Gosavi TD, Shorvon SD, Köhler S, Walker MC. Change in mortality of generalized convulsive status epilepticus in high‐income countries over time. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;1(76):897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lattanzi S, Giovannini G, Brigo F, Orlandi N, Trinka E, Meletti S. Status epilepticus with prominent motor symptoms clusters into distinct electroclinical phenotypes. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:2694–2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lattanzi S, Giovannini G, Brigo F, Orlandi N, Trinka E, Meletti S. Acute symptomatic status epilepticus: splitting or lumping? A proposal of classification based on real‐world data. Epilepsia. 2023;64:e200–e206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lattanzi S, Trinka E, Brigo F, Meletti S. Clinical scores and clusters for prediction of outcomes in status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;140:109110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leitinger M, Trinka E, Giovannini G, Zimmermann G, Florea C, Rohracher A, et al. Epidemiology of status epilepticus in adults: a population‐based study on incidence, causes, and outcomes. Epilepsia. 2019;60:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sutter R, Semmlack S, Spiegel R, Tisljar K, Rüegg S, Marsch S. Distinguishing in‐hospital and out‐of‐hospital status epilepticus: clinical implications from a 10‐year cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1156–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brigo F, Turcato G, Lattanzi S, Orlandi N, Turchi G, Zaboli A, et al. Out‐of‐hospital versus in‐hospital status epilepticus: The role of etiology and comorbidities. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:2885–2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vignatelli L, Rinaldi R, Baldin E, Tinuper P, Michelucci R, Galeotti M, et al. Impact of treatment on the short‐term prognosis of status epilepticus in two population‐based cohorts. J Neurol. 2008;255:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE, Shinnar S, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus—Report of theILAETask Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1515–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rossetti AO, Claassen J, Gaspard N. Status epilepticus in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uppal P, Cardamone M, Lawson JA. Outcomes of deviation from treatment guidelines in status epilepticus: A systematic review. Seizure. 2018;58:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sathe AG, Underwood E, Coles LD, Elm JJ, Silbergleit R, Chamberlain JM, et al. Patterns of benzodiazepine underdosing in the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial. Epilepsia. 2021;62:795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vignatelli L, Tonon C, D'Alessandro R. Incidence and short‐term prognosis of status epilepticus in adults in Bologna, Italy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vignatelli L, Rinaldi R, Galeotti M, de Carolis P, D'Alessandro R. Epidemiology of status epilepticus in a rural area of northern Italy: a 2‐year population‐based study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Govoni V, Fallica E, Monetti VC, Guerzoni F, Faggioli R, Casetta I, et al. Incidence of status epilepticus in southern Europe: a population study in the health district of Ferrara. Italy Eur Neurol. 2008;59:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giovannini G, Monti G, Polisi MM, Mirandola L, Marudi A, Pinelli G, et al. A one‐year prospective study of refractory status epilepticus in Modena. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giovannini G, Monti G, Tondelli M, Marudi A, Valzania F, Leitinger M, et al. Mortality, morbidity and refractoriness prediction in status epilepticus: comparison of STESS and EMSE scores. Seizure. 2017;46:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giovannini G, Pasini F, Orlandi N, Mirandola L, Meletti S. Tumor‐associated status epilepticus in patients with glioma: Clinical characteristics and outcomes. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;101:106370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orlandi N, Giovannini G, Rossi J, Cioclu MC, Meletti S. Clinical outcomes and treatments effectiveness in status epilepticus resolved by antiepileptic drugs: A five‐year observational study. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5:166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mutti C, Sansonetti A, Monti G, Vener C, Florindo I, Vaudano AE, et al. Epidemiology, management and outcome of status epilepticus in adults: single‐center Italian survey. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:2003–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;20(335):806–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vignatelli L, Tontini V, Meletti S, Camerlingo M, Mazzoni S, Giovannini G, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of status epilepticus in adults: A systematic review. Epilepsia. 2024;65:1512‐1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Minicucci F, Ferlisi M, Brigo F, Mecarelli O, Meletti S, Aguglia U, et al. Management of status epilepticus in adults. Position paper of the Italian league against epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;102:106675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, Alldredge B, Arya R, Bainbridge J, et al. Evidence‐based guideline: treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: report of the guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Epilepsies in children, young people and adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beuchat I, Novy J, Rosenow F, Kellinghaus C, Rüegg S, Tilz C, et al. Staged treatment response in status epilepticus: Lessons from the SENSE registry. Epilepsia. 2024;65:338–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brigo F, Nardone R, Tezzon F, Trinka E. Nonintravenous midazolam versus intravenous or rectal diazepam for the treatment of early status epilepticus: A systematic review with meta‐analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, et al. Intramuscular versus Intravenous Therapy for Prehospital Status Epilepticus. New Engl J Med. 2012;16(366):591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prasad K, Krishnan PR, Al‐Roomi K, Sequeira R. Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Costa C, Nardi Cesarini E, Eusebi P, Franchini D, Casucci P, De Giorgi M, et al. Incidence and antiseizure medications of post‐stroke epilepsy in Umbria: A population‐based study using healthcare administrative databases. Front Neurol. 2021;12:800524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferlisi M, Hocker S, Trinka E, Shorvon S. The anesthetic drug treatment of refractory and super‐refractory status epilepticus around the world: Results from a global audit. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;101:106449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jacobwitz M, Mulvihill C, Kaufman MC, Gonzalez AK, Resendiz K, MacDonald JM, et al. Ketamine for management of neonatal and pediatric refractory status epilepticus. Neurology. 2022;20(99):e1227–e1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Souidan H, Machado RA, Lagnf A, Elsayed M. Double antiglutamatergic treatment in patients with status epilepticus: A case series. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;137:108954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosati A, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Ketamine for Refractory Status Epilepticus: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:997–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson S, Goad N, Taylor E, Hanson J, Hanif S. Ketamine or traditional continuous anesthetics in refractory or super‐refractory status epilepticus. Crit Care Med. 2023;51:538. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kellinghaus C, Rossetti AO, Trinka E, Lang N, May TW, Unterberger I, et al. Factors predicting cessation of status epilepticus in clinical practice: data from a prospective observational registry (SENSE). Ann Neurol. 2019;85:421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guterman EL, Sanford JK, Betjemann JP, Zhang L, Burke JF, Lowenstein DH, et al. Prehospital midazolam use and outcomes among patients with out‐of‐hospital status epilepticus. Neurology. 2020;15(95):e3203–e3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guterman EL, Sporer KA, Newman TB, Crowe RP, Lowenstein DH, Josephson SA, et al. Real‐world midazolam use and outcomes with out‐of‐hospital treatment of status epilepticus in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80:319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kohle F, Madlener M, Bruno EF, Fink GR, Limmroth V, Burghaus L, et al. Status epilepticus and benzodiazepine treatment: use, underdosing and outcome–insights from a retrospective, multicentre registry. Seizure. 2023;107:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cetnarowski A, Cunningham B, Mullen C, Fowler M. Evaluation of intravenous lorazepam dosing strategies and the incidence of refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2023;190:107067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gaspard N. Benzodiazepines for out‐of‐hospital status epilepticus: do or do not! There is no try! Epilepsy curr. 2021;21:96–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. De Stefano P, Baumann SM, Grzonka P, Sarbu OE, De Marchis GM, Hunziker S, et al. Early timing of anesthesia in status epilepticus is associated with complete recovery: a 7‐year retrospective two‐center study. Epilepsia. 2023;64:1493–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rossetti AO, Alvarez V, Januel JM, Burnand B. Treatment deviating from guidelines does not influence status epilepticus prognosis. J Neurol. 2013;260:421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DATA S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.