Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder marked by both motor and non-motor symptoms that necessitate ongoing clinical evaluation and medication adjustments. Home-based wearable sensor monitoring offers a detailed and continuous record of patient symptoms, potentially enhancing disease management. The EmPark-PKG study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the Parkinson’s KinetoGraph (PKG), a wearable sensor device, in monitoring and tracking the progression of motor symptoms over 12 months in Emirati and non-Emirati PD patients. Fifty PD patients (32% Emirati, 68% non-Emirati) were assessed at baseline and a 12-month follow-up. Clinical evaluations included levodopa equivalent daily dosage (LEDD) and motor and non-motor assessments. Concurrently, the PKG provided metrics such as bradykinesia score (BKS) and dyskinesia score (DKS). Statistical analyses were conducted to determine changes from baseline to six months, differences between Emirati and non-Emirati groups, and correlations between PKG metrics and clinical assessments. Significant reductions in LEDD and improvements in both motor and non-motor scores were observed from baseline to six months (p < 0.05). PKG-guided medication adjustments were associated with enhanced motor and non-motor outcomes (p < 0.05). Specifically, non-Emirati patients exhibited a significant reduction in LEDD (Z = − 2.010, p = 0.044), whereas Emirati patients did not (Z = − 0.468, p = 0.640). Both groups showed significant improvements in motor scale scores and motor complication scores. Spearman correlation analysis revealed strong relationships between PKG metrics and subjective clinical assessments (p < 0.001). The EmPark-PKG study demonstrates the potential benefits of remote PKG monitoring for personalised motor symptom management in PD. PKG supports a stepped care paradigm by enabling bespoke medication titration based on objective data, facilitating tailored and effective patient care.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, UAE, PKG, Remote monitoring, Objective measurements

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterised by motor and non-motor symptoms (NMS) that significantly impact the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their caregivers (Sauerbier et al. 2016). PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide, with a global prevalence ranging from 100 to 200 cases per 100,000 people, with the incidence rate increasing with age and a burden that is expected to be felt with significant societal impact in the Middle East, Asia and Africa (Ou et al. 2021; Reeve et al. 2014). Although PD primarily affects older adults, it can also present in younger populations, contributing to its significant healthcare burden (Kolicheski et al. 2022). As the disease progresses, the emergence of motor and non-motor fluctuations and the management are complicated by a low number of PD experts and limited access to tertiary PD centres.

In the Middle East, particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the prevalence and impact of PD are gaining increasing recognition. The UAE has undergone a rapid demographic and epidemiological transition, with a growing ageing population and a rise in incidences of chronic neurodegenerative diseases (El Masri et al. 2021). Global prevalence studies analysing data between 1990 to 2019 conclude the Middle East and North Africa have a PD prevalence of 82.6 per 100,000 population. There has been a clear upward trend over the last three decades compared to previous reports (Safiri et al. 2023). The EmPark study reports evidence of a low prevalence of PD in some Arab communities, such as the Al Thuqbah region of Saudi Arabia (Metta et al. 2022). However, other areas, such as the North African Arabs, have the highest prevalence in the Middle East (Metta et al. 2022). The figures and data from the UAE and other such Middle Eastern countries may vary, reflecting the underrepresentation of the actual burden due to underdiagnosis, limited awareness, cultural factors, and stigma that exists around neurodegenerative conditions (Metta et al. 2022; Alokley et al. 2024). Exploration of this population is becoming critical, with recent studies comparing Emirati and non-Emirati populations finding motor differences and levodopa response variations (Metta et al. 2022, 2024).

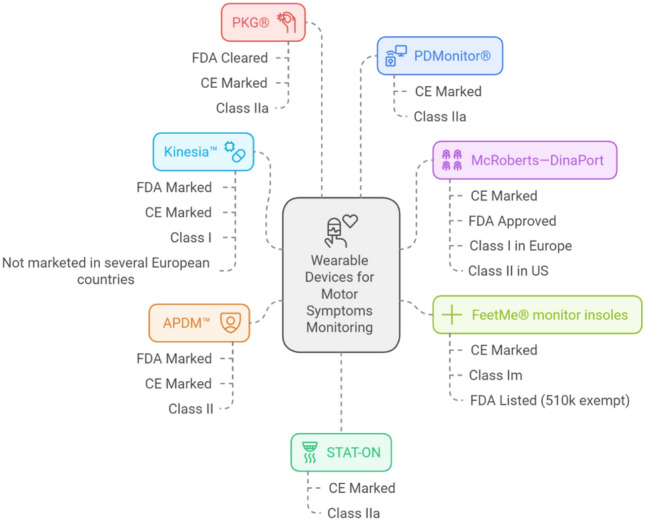

Despite advances in medical and surgical treatments, managing the diverse symptoms of PD remains a complex challenge. Motor symptoms, including tremors, bradykinesia, and dyskinesia, are commonly assessed using clinical scales and questionnaires but lack integration with objective monitoring. The UAE’s healthcare service is moving to encourage further development in this field, with the Ministry of Health working to enhance options for telemedicine and technology-integrated healthcare (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Objective monitors for Parkinson’s motor symptoms [17–25]. CE Conformite Europeenee, FDA Food and Drug Administration

The Parkinson’s KinetoGraph (PKG), a wrist-worn watch, quantifies the kinematics of motor manifestations, allowing for objective evidence for home monitoring of PD patients (Sundgren et al. 2021). The PKG-derived scores, including Bradykinesia Score (BKS), Dyskinesia Score (DKS), Percentage Tremor Time (PTT), and Percentage Time Immobile (PTI), offer a detailed and objective measure of motor function, supplementing traditional clinical scales and examinations. Recent reports suggest the usefulness of the PKG in detecting and treating problems such as nocturnal akinesis in PD (Poplawska-Domaszewicz et al. 2024b). Furthermore, the PKG helps measure and understand NMS, such as sleep (McGregor et al. 2018), impulsive behaviour disorder (ICD), and gastrointestinal (GIT) symptoms (van Wamelen et al. 2019).

The PKG is also integral to the recently described dashboard for PD and related stepped-care paradigms (Chaudhuri et al. 2022; Qamar et al. 2023; Poplawska-Domaszewicz et al. 2024a). By integrating objective monitoring data provided by the PKG alongside clinical assessments, the EmPark-PKG substudy aims to fill some of these knowledge gaps by exploring the progression of PD symptoms, caregiver burden, and therapeutic outcomes in a cohort of Emirati and non-Emirati patients. Thus, it will enhance our understanding of PD in the UAE context (Caballol et al. 2023; Perez-Lopez et al. 2016; Rodriguez-Molinero et al. 2015, 2017, 2019; Sama et al. 2017; Sayeed et al. 2015; Rodriguez-Martin et al. 2017; Giladi et al. 2009).

Methodology

Study design

This 12-month longitudinal observational cohort study was conducted at King’s College Hospital Dubai, UAE, from August 2023 to August 2024. The EmPark-PKG is a substudy of the greater EmPark study (Metta et al. 2022). Patients were recruited from the Movement Disorder Service at King’s College Hospital Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Patients recruited were invited for a baseline visit for assessments with their caregivers. The patients were asked after the baseline visit to wear a PKG wrist-worn device on their symptom-dominant side for seven consecutive days. A pre-paid envelope was provided for them to ship the device back to the hospital for review, usually a neurologist report of the PKG, within 24 h of receiving the returned device. After reviewing the PKG report, the neurologist performed a virtual consultation within two weeks of the report to make any adjustments to management plans. The implementation of the changes was then assessed at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups, whereby all assessments were repeated, including a further 7-day PKG recording.

Objectives

The EmPark-PKG study aims to evaluate whether home monitoring of PD patients at home can test and track the progression of their symptoms of PD in patients from the UAE over 12 months. It also seeks to assess the use of the PKG in clinical practice on the clinical outcomes of Emirati and Non-Emirati PD patients over 12 months.

Study population

The study included 50 patients diagnosed with idiopathic PD as defined by the UK PD Brain Bank Criteria, with age greater than or equal to 40 years old and meeting the criteria for using PKG (unstable PD management, wearing off phenomena, nocturnal akinesia, dyskinesia, motor fluctuations, non-motor fluctuations, and sleep disturbances). Patients were excluded based on having significant co-morbid neurological or psychiatric disorders, including those who were unwilling or unable to provide informed consent. Patients were required to be able to wear the PKG watch for seven days consecutively. Patients were excluded if deemed unable to comply or withdrawn if they did not complete the 7-day watch data collection.

Participants were stratified into two groups based on ethnicity: Emirati and non-Emirati. The Emirati group consisted of UAE locals who identified their ethnicity as Emirati; all others were considered non-Emirati.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the UAE Research and Development Board of King’s College Hospital Dubai, and participants provided written informed consent before enrolment. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by local ethical approval K/D/REC/K17/1024. Furthermore, the study was under the ongoing UK portfolio adopted Nonmotor International Longitudinal Study (NILS) at the King’s Parkinson’s Foundation Centre of Excellence at Kings College Hospital in London.

Data collection

Data was collected at baseline, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up outpatient clinic appointments. The data collected is as follows:

Demographics and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, disease duration, motor subtype (akinetic subtype (AKD), tremor (TD), mixed subtype (MD)) and levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD), were collected at both time points.

Motor function was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr (HY) (Hoehn and Yahr 1967) staging system from 1 to 5 and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parts 3 (UPDRS3) and 4 (UPDRS4). UPDRS3 collected data on the motor symptoms of PD, ranging from tremor to gait, while UPDRS4 collected data on motor complications such as dyskinesia and early morning dystonia. A trained clinician performed all three clinical assessments.

Nonmotor function was assessed using the validated self-completed Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire (NMSQ) (Chaudhuri et al. 2006), covering symptoms ranging from depression to neuropsychiatric manifestations.

Cognitive functioning was assessed using the validated Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Dautzenberg et al. 2020), which interprets scores over 27/30 as normal cognitive function and under 26 as cognitive impairment.

Patients were asked to wear a PKG watch for seven consecutive days. The PKG logger records accelerometer data while the patient wears the watch on their dominant (or symptom-dominant side) wrist. The algorithm applied to the data collected produces the mean measurement of severity for bradykinesia (BKS), dyskinesia (DKS), tremor (PTT), and immobility (PTI). No feedback was given to the patient during the recording period to reduce the risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 29.0. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk Test. Continuous variables were summarised as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables were summarised as frequencies and percentages. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was applied for nonparametric continuous data to compare baseline and 12-month follow-up scores. Spearman Correlation Coefficients were applied to assess the relationship between clinical variables at different time points. The McNamara test was used to evaluate changes in categorical variables over time.

Results

Baseline descriptive analysis

Fifty idiopathic PD patients were recruited and analysed for the EmPark-PKG project. Of the 50 participants, 32% were Emirati, and 68% were non-Emirati. The Emirati subgroup had more women than the non-Emirati group (31.2% and 26.5%, respectively). The most common PD motor subtype in both cohorts was the AKD subtype (52%), and similarly, the baseline disease duration, LEDD, HY stage, MoCA score, NMSQ score, and NMS burden were similar for both cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

EmPARK cohort baseline demographics

| Non-emirati | Emirati | EmPARK Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 34 (68%) | 16 (32%) | 50 (100%) |

| Age (years) | 71.5 ± 6.9 | 63.0 ± 11.1 | 66.98 ± 9.954 |

| Gender | |||

| - Male | 25 (73.5%) | 11 (68.8%) | 36 (72%) |

| - Female | 9 (26.5%) | 5 (31.2%) | 14 (28%) |

| PD Type | |||

| - AKD | 9 (26.5%) | 17 (68.8%) | 26 (52%) |

| - TD | 4 (11.8%) | 15 (21.2%) | 19 (38%) |

| - Mixed | 3 (8.8%) | 2 (4.8%) | 5 (10%) |

| Disease duration (years) | 6.1 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 5.74 ± 2.497 |

| LEDD (mg) | 739.4 ± 243.2 | 693.4 ± 165.5 | 739.40 ± 243.163 |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.690 ± 0.4726 |

| MoCA total score | 29.7 ± 0.6 | 29.7 ± 0.6 | 29.72 ± 0.573 |

| NMSQ total score | 13.6 ± 2.3 | 13.6 ± 2.3 | 13.58 ± 2.331 |

| UPDRS Part III total score | 21.6 ± 3.9 | 25.8 ± 4.1 | 25.82 ± 4.114 |

| UPDRS Part IV total score | 6.7 ± 3.2 | 9.6 ± 5.5 | 9.60 ± 5.473 |

AKD akinetic dominant, TD tremor dominant, LEDD levodopa equivalent daily dose, MoCA Montreal cognitive assessment, NMSQ nonmotor symptoms questionnaire, UPDRS unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale, PD Parkinson’s disease

Comparison analysis of baseline to 12 months

Emirati and non-Emirati groups significantly improved several clinical scale scores over 12 months (Table 2). However, the LEDD reduction at 12 months was only statistically significant in non-Emirati patients compared to Emirati patients, and both groups had no change in the cognitive assessment score as recorded by MOCA scores. Additionally, a statistically significant improvement was found in Predicted OFF (PO) from 12 months for both ethnic groups. However, Unpridected OFF (UO), despite a decrease in scores over 12 months (Non-Emirati mean decrease of 0.06 and Emirati mean decrease of 0.12), was not statistically significant in either group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison between ethnic groups on change from baseline to 12-months (continuous variables)

| Non-Emirati | Emirati | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | SD | Z | p | Median | Mean | SD | Z | p | |

| LEDD | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 700.00 | 728.53 | 226.12 | − 2.640 | 0.008* | 850.00 | 762.50 | 282.55 | − 1.427 | 0.154 |

| 12-months | 600.00 | 635.29 | 132.30 | 650.00 | 706.25 | 161.12 | ||||

| BKS | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 15.00 | 16.94 | 3.68 | − 5.041 | < 0.001* | 16.00 | 16.69 | 4.21 | − 3.049 | 0.002* |

| 12-months | 12.00 | 13.06 | 2.27 | 12.00 | 13.00 | 2.63 | ||||

| DKS | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 10.00 | 18.74 | 12.32 | − 3.923 | < 0.001* | 10.50 | 17.31 | 12.20 | − 2.974 | 0.003* |

| 12-months | 10.00 | 12.26 | 5.01 | 10.00 | 11.94 | 7.27 | ||||

| PTT | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 4.00 | 6.09 | 4.90 | − 4.209 | < 0.001* | 2.00 | 4.44 | 4.47 | − 2.971 | 0.003* |

| 12-months | 2.00 | 3.44 | 3.01 | 1.00 | 2.56 | 3.03 | ||||

| PTI | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 14.00 | 15.88 | 4.89 | − 4.896 | < 0.001* | 15.00 | 16.81 | 5.05 | − 3.420 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months | 10.00 | 9.94 | 0.78 | 10.00 | 9.88 | 0.96 | ||||

| UPDRS3 | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 25.00 | 26.35 | 4.13 | − 5.119 | < 0.001* | 24.00 | 24.69 | 3.98 | − 3.573 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months | 20.00 | 19.24 | 3.41 | 17.00 | 18.63 | 3.24 | ||||

| UPDRS4 | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 7.00 | 9.94 | 5.53 | − 4.473 | < 0.001* | 8.50 | 8.88 | 5.45 | − 2.816 | 0.005* |

| 12-months | 6.50 | 5.91 | 3.02 | 7.00 | 6.19 | 3.04 | ||||

| MoCA | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 30.00 | 29.71 | 0.63 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 30.00 | 29.75 | 0.45 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| 12-months | 30.00 | 29.71 | 0.63 | 30.00 | 29.75 | 0.45 | ||||

| NMSQ | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 14.00 | 13.47 | 2.57 | − 5.058 | < 0.001* | 14.00 | 13.81 | 1.80 | − 3.443 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months | 10.00 | 10.18 | 0.72 | 10.00 | 10.13 | 0.50 | ||||

| PDQ8 | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 20.00 | 18.73 | 6.96 | − 4.722 | < 0.001* | 16.00 | 19.25 | 6.69 | − 3.310 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months | 12.00 | 12.41 | 3.90 | 12.00 | 12.75 | 3.33 | ||||

| ZCB | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 48.00 | 48.21 | 20.99 | − 4.727 | < 0.001* | 53.00 | 52.50 | 21.53 | − 3.315 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months | 30.00 | 26.76 | 9.56 | 30.00 | 27.25 | 9.00 | ||||

LEDD levodopa equivalent daily dose, BKS bradykinesia score, DKS dyskinesia score, PTT percentage time tremor, PTI percentage time immobile, UPDRS unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale, MoCA Montreal cognitive assessment, NMSQ nonmotor symptoms questionnaire, PDQ Parkinson’s disease questionnaire, ZCB Zarit caregiver burden

*Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p < 0.05

Table 3.

Comparison between ethnic groups on change from baseline to 12-months

| Non-Emirati | Emirati | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | p | Mean | SD | N | p | |

| PO | ||||||||

| Baseline | 0.71 | 0.46 | 34 | < 0.001* | 0.50 | 0.52 | 16 | 0.008* |

| 12-months | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| UO | ||||||||

| Baseline | 0.68 | 0.48 | 34 | 0.774 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 16 | 0.727 |

| 12-months | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.50 | ||||

*McNemar Test p < 0.05

N number, PO predictable OFF, UO unpredictable OFF, SD standard deviation

Correlations between PKG and clinical assessment

The correlation analyses revealed significant differences across both groups in various clinical measures during 12-month follow-up (Table 4). At baseline, the correlation between BKS and UPDRS3 had strong significance for non-Emirati participants (ρ = 0.926, p < 0.001) but not for Emirati participants (ρ = 0.409, p = 0.115). Both groups exhibited strong significant correlations between DKS and UPDRS4 (Emirati: ρ = 0.901, p < 0.001; non-Emirati: ρ = 0.890, p < 0.001). For PTI and EDS, the correlations were strongly significant for both groups (Emirati: ρ = 0.751, p < 0.001; non-Emirati: ρ = 0.925, p < 0.001). At 12 months, significant correlations were observed between BKS and UPDRS3 for non-Emirati participants (ρ = 0.765, p < 0.001), while Emirati participants showed a negligible correlation (ρ = 0.031, p = 0.910). The correlations between DKS and UPDRS4 remained significant for both groups (Emirati: ρ = 0.678, p = 0.004; non-Emirati: ρ = 0.751, p < 0.001). Additionally, non-Emirati participants exhibited significant correlations between PTI and EDS (ρ = 0.779, p < 0.001) at follow-up.

Table 4.

Correlation between PKG outputs and clinical assessments for both ethnic groups

| Emirati | Non-Emirati | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρa | pb | ρa | pb | |

| Baseline | ||||

| BKS & UPDRS3 | 0.409 | 0.115 | 0.926 | < 0.001* |

| DKS & UPDRS4 | 0.901 | < 0.001* | 0.890 | < 0.001* |

| PTT & UPDRS3 | − 0.270 | 0.313 | 0.067 | 0.706 |

| PTI & EDS | 0.751 | < 0.001* | 0.925 | < 0.001* |

| PTI & EMD | 0.650 | 0.006* | 0.850 | < 0.001* |

| 12-months follow-up | ||||

| BKS & UPDRS3 | 0.017 | 0.951 | 0.708 | < 0.001* |

| DKS & UPDRS4 | 0.711 | 0.002* | 0.633 | < 0.001* |

| PTT & UPDRS3 | 0.126 | 0.643 | 0.239 | 0.174 |

| PTI & EDS | 0.640 | 0.008* | 0.688 | < 0.001* |

| PTI & EMD | 0.060 | 0.825 | 0.048 | 0.789 |

BKS bradykinesia score; DKS dyskinesia score; PTT percentage time tremor; PTI percentage time immobile; UPDRS unified Parkinson’s disease rating score; EDS excessive daytime somnolence; EMD early morning dystonia

aSpearman correlation coefficient

b*p < 0.05 statistical significance

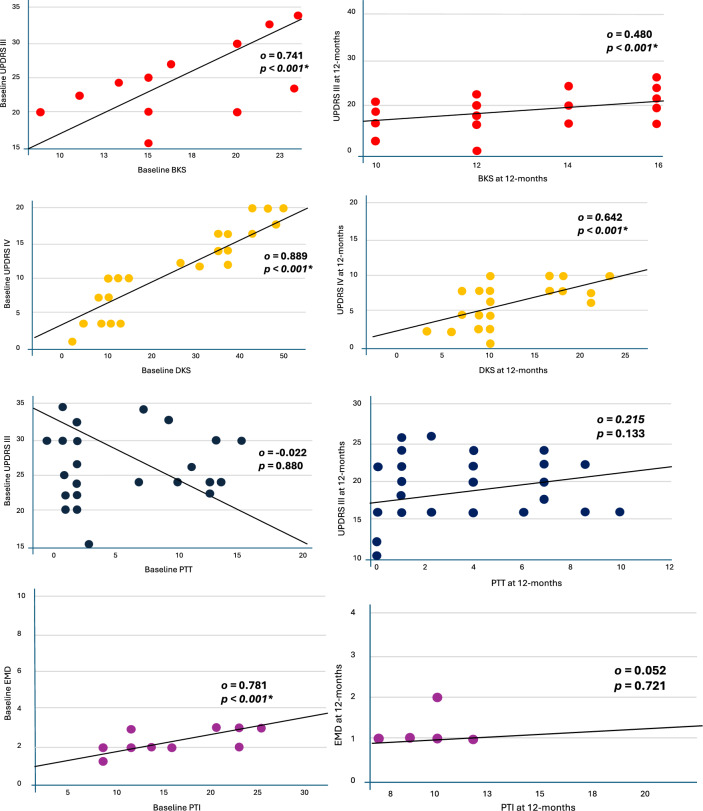

The Spearman correlation calculation of the entire cohort examining the relationship between PKG measures and their association with clinical tools at baseline and 12-month follow-up showed similar results to the grouped analysis (Fig. 2). There was a strong positive correlation between BKS and UPDRS3 at baseline (ρ = 0.741, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.577, 0.847]), and at follow-up (ρ = 0.480, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.225, 0.674]). Similarly, DKS and UPDRS4 had a strong positive correlation at baseline (ρ = 0.889, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.809, 0.937]), and at follow-up (ρ = 0.642, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.436, 0.784]). There was no statistically significant correlation between PTT and UPDRS at either baseline (ρ = − 0.022, p < 0.880, 95% CI [− 0.306, 0.266]) or follow-up (ρ = 0.215, p < 0.133, 95% CI [− 0.075, 0.472]). There was a statistically significant correlation between PTI and EMD at baseline (ρ = 0.781, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.638, 0.872]), but not at 12 months (ρ = 0.052, p = 0.721, 95% CI [− 0.238, 0.333]).

Fig. 2.

Scatter Graph of Spearman Correlation Calculation for EmPark Cohort. This scatter graph outlines the calculations of correlations between clinical tools and objective monitoring measures for the cohort, which is not divided into groups. UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale, BKS bradykinesia score, PTI percentage time immobile, PTT percentage time tremor, EMD early morning dystonia

Discussion

The EmPARK-PKG study, the first of its kind using home-based objective monitoring and a validated wearable sensor for PD, showed the following key outcomes:

Baseline PKG records allowed bespoke and personalised dopaminergic treatment adjustments, improving LEDD scores.

NMS burden, as judged by total scores in NMSQ, improved

There were differences between Emirati and non-Emirati groups, even allowing for the small number of patients in each group.

Research has explored the progression of PD in different ethnic cohorts, given the growing prevalence of PD in these cohorts (Ben-Joseph et al. 2020). Evidence is emerging showing different ethnic groups have differences in PD symptomology and, subsequently, differences in treatment responses. African and African Caribbean PD populations have been reported to have more atypical features, including hypo-responsiveness to levodopa (Chaudhuri et al. 2000). Asian PD cohorts are reported to have more freezing of gait and experience dyskinesia; subsequently, treatment with levodopa is kept at lower doses for these groups (Yu et al. 2017; Woitalla et al. 2007). Yemenite Jews with PD are reported to have a higher rate of disease progression alongside increased progression of cognition issues and mood disturbances (Djaldetti et al. 2008). Despite this growing interest in the ethnic variations of PD subtypes, Emirati and Middle Eastern patients with PD are significantly underrepresented in the field (Metta et al. 2022). The EmPARK-PKG study aimed to evaluate the progression of PD in Emirati and non-Emirati patients over 12 months and assess the utility of the PKG in clinical practice for this population group. Given the growing integration of technology within healthcare, ranging from wearable monitor devices to artificial intelligence diagnostic usage (Moreau et al. 2023), the use of the PKG in the study becomes even more relevant. The findings from this study provide valuable insights into the differences and similarities in clinical outcomes and PKG metrics between these groups.

The EmPARK-PKG cohort found there to be more men diagnosed with PD than women (72% men, 28% women), resembling other cohort studies (Zirra et al. 2023; Moisan et al. 2016; Safiri et al. 2023). The increasing incidences of PD in Middle Eastern countries reported by previous studies are complemented by our results showing the Emirati cohort being younger (62.0 ± 11.1 years) than the non-Emirati group (71.5 ± 6.9 years) (Bach et al. 2011; Collaborators 2018; Metta et al. 2022; Safiri et al. 2023; Khalil et al. 2020). The Early-Onset PD (EOPD) prevalence being higher in Emirati cohorts has been discussed previously and proposed to be partly attributed to the consanguinity in Arab populations (Collaborators 2020; Khalil et al. 2020). However, studies remain limited in exploring this particular relation. Furthermore, the AKD subtype of PD was consistently higher in our cohorts, irrespective of ethnicity, like that found in other PD cohorts (Rajput et al. 2017; Ren et al. 2021). Evidence suggests AKD subtype cohorts often progress to faster cognitive deterioration (Burn et al. 2003), higher NMS burden (Ba et al. 2016), particularly depression, and generally progress faster (Lewis et al. 2005). Our data emphasise the importance of such phenotyping of symptoms and a personalised approach. Given that our data shows Emiratis as being younger and having the AKD subtype as the frequent motor subtype, the prognostic implication is essential to consider during consultations.

The usefulness of the PKG as an objective, continuous monitoring device in clinical practice was supported by the results showing improvement in several observed clinical parameters over 12 months. The LEDD score, NMSQ scores, and UPDRS scores (for parts III and IV) improved over 12 months with a decrease in scores, which was statistically significant. However, no change in cognitive function was observed, irrespective of ethnicity. These results indicate an overall improvement in both motor and nonmotor management and a reduction in medication burden, reflecting better disease management through PKG-guided adjustments. This improvement echoes Joshi et al.’s (2019) report, which found that by applying PKG in outpatient clinics, there was an improvement in clinician and patient dialogue by 59% and an improvement in treatment plans in 79% of patient consultations (Joshi et al. 2019). According to Sundergren et al. (2021), the parameters measured by PKG were nearly identical to clinical assessments, thus facilitating the adjustment of treatment plans using PKG parameters (Sundgren et al. 2021).

A few notable differences emerge between the Emirati and non-Emirati groups. Despite both groups having a reduction in levodopa over 12 months, the non-Emirati patients had a statistically significant decrease (Z =− 2.010, p = 0.044), but Emirati patients reduction was only numerical (Z = − 0.468, p = 0.640). This suggests a more pronounced response to medication adjustments guided by the PKG in non-Emirati patients than in Emirati patients. The discrepancy in LEDD dose between the cohorts is a new finding, which could be attributed to caution in dosing and change of treatment plans. However, as assessed by the PKG, motor function improved in both cohorts despite the difference in LEDD dose reduction, allowing clinicians to gain objective results in a patient’s progression over 12 months. Until now, clinicians have relied upon patient feedback, which is vital; however, by applying the PKG to clinical practice in our cohort, we see an ability to tailor patient plans.

The correlation analysis shows the relationship between PKG metrics and clinical assessments. At baseline, the non-Emirati patients exhibited a strong correlation between BKS and UPDRS3 (o = 0.926, p < 0.001), which was not significant in Emirati patients (o = 0.409, p = 0.115). This could indicate that the PKG metrics are more reflective of clinical severity in non-Emirati patients. Both groups showed significant correlations between DKS and UPDRS4, highlighting the utility of PKG in capturing dyskinesia severity across different ethnicities. The validation of the objective PKG algorithm, with its ability to correlate against validated subjective clinical tools, has been explored before.

Furthermore, the strong positive correlations between PKG-derived metrics and clinical scores suggest that PKG can reliably reflect disease severity and treatment response. This becomes particularly important in diverse populations where clinical presentations and responses to treatment may vary. Bhidayasiri et al. (2023) recently highlighted the disparities in PD care due to regional access and resource constraints (Bhidayasiri et al. 2023), emphasising the urgent need for validated tools that can be deployed remotely to improve care for all PD patients, regardless of geographic or healthcare access barriers. Our study offers concrete evidence of the effectiveness of a continuous objective monitoring device, which provides critical data that supports meaningful clinical interventions.

Our study has some limitations, primarily due to the relatively small sample size, which may have affected the analysis, particularly for the Emirati group. The correlation analysis reveals that when analysed separately, the Emirati group shows no statistically significant results, whereas a strong correlation emerges when assessed alongside the entire cohort. Future research should incorporate larger sample sizes to validate these findings and investigate the potential underlying factors contributing to the observed ethnic differences in clinical outcomes. Additionally, including PD patients at various stages of the disease would offer a more comprehensive understanding of symptom changes throughout disease progression, which may differ within the Emirati population. Expanding the study to include other sites across the Middle East and globally would also enhance the diversity of comparison groups and provide a broader perspective.

In conclusion, the EmPARK-PKG study demonstrates significant improvements in clinical outcomes for PD patients over 12 months of follow-up, with differences between Emirati and non-Emirati patients. The PKG has proven to be a valuable tool in guiding clinical decisions, leading to better management of PD symptoms and medication dosages. These findings support the integration of PKG into routine clinical practice to achieve personalised PD management.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Parkinson’s Centre of Excellence King's Dubai team (Therese Masagnay, Dr Hasna Hussein, Mr Afsal Nalarakettil, Mr Ehabadly Awad) and PD patients attending the King’s College Hospital Dubai. Furthermore, the authors thank King’s College Parkinson’s Centre of Excellence London UK Research and Clinical team for their support.

Author contributions

V.M. and K.R.C. conceptualised the project. M.A.Q. and V.M. performed the analysis and initial manuscript draft. All authors contributed equally towards the revised writing, review, editing, and finalisation of the review.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the EmPark-PKG study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please email vin.metta@nhs.net.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alokley AA, Alhubail FM, Al Omair AM, Alturki RA, Alhaddad RM, Al Mousa AM, Busbait SA, Alnaim MA (2024) Assessing the perception of Parkinson’s disease in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia among the visitors of a public campaign: before and after survey. Front Neurol 15:1365339. 10.3389/fneur.2024.1365339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba F, Obaid M, Wieler M, Camicioli R, Martin WR (2016) Parkinson disease: the relationship between non-motor symptoms and motor phenotype. Can J Neurol Sci 43(2):261–267. 10.1017/cjn.2015.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach JP, Ziegler U, Deuschl G, Dodel R, Doblhammer-Reiter G (2011) Projected numbers of people with movement disorders in the years 2030 and 2050. Mov Disord 26(12):2286–2290. 10.1002/mds.23878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Joseph A, Marshall CR, Lees AJ, Noyce AJ (2020) Ethnic variation in the manifestation of parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. J Parkinsons Dis 10(1):31–45. 10.3233/JPD-191763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhidayasiri R, Kalia LV, Bloem BR (2023) Tackling Parkinson’s disease as a global challenge. J Parkinsons Dis 13(8):1277–1280. 10.3233/JPD-239005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn DJ, Rowan EN, Minett T, Sanders J, Myint P, Richardson J, Thomas A, Newby J, Reid J, O’Brien JT, McKeith IG (2003) Extrapyramidal features in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: a cross-sectional comparative study. Mov Disord 18(8):884–889. 10.1002/mds.10455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballol N, Bayes A, Prats A, Martin-Baranera M, Quispe P (2023) Feasibility of a wearable inertial sensor to assess motor complications and treatment in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 18(2):e0279910. 10.1371/journal.pone.0279910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Hu MT, Brooks DJ (2000) Atypical parkinsonism in Afro-Caribbean and Indian origin immigrants to the UK. Mov Disord 15(1):18–23. 10.1002/1531-8257(200001)15:1%3c18::aid-mds1005%3e3.0.co;2-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AH, Stocchi F, Sethi K, Odin P, Brown RG, Koller W, Barone P, MacPhee G, Kelly L, Rabey M, MacMahon D, Thomas S, Ondo W, Rye D, Forbes A, Tluk S, Dhawan V, Bowron A, Williams AJ, Olanow CW (2006) International multicenter pilot study of the first comprehensive self-completed nonmotor symptoms questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease: the NMSQuest study. Mov Disord 21(7):916–923. 10.1002/mds.20844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Titova N, Qamar MA, Murasan I, Falup-Pecurariu C (2022) The dashboard vitals of parkinson’s: not to be missed yet an unmet need. J Pers Med. 10.3390/jpm12121994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators GBDPsD (2018) Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 17(11):939–953. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautzenberg G, Lijmer J, Beekman A (2020) Diagnostic accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for cognitive screening in old age psychiatry: determining cutoff scores in clinical practice. Avoiding spectrum bias caused by healthy controls. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 35(3):261–269. 10.1002/gps.5227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djaldetti R, Hassin-Baer S, Farrer MJ, Vilarino-Guell C, Ross OA, Kolianov V, Yust-Katz S, Treves TA, Barhum Y, Hulihan M, Melamed E (2008) Clinical characteristics of Parkinson’s disease among Jewish Ethnic groups in Israel. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 115(9):1279–1284. 10.1007/s00702-008-0074-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Masri J, Dankar R, El Masri D, Chanbour H, El Hage S, Salameh P (2021) The Arab Countries’ contribution to the research of neurodegenerative disorders. Cureus 13(8):e17589. 10.7759/cureus.17589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBDD Collaborators (2020) Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258):1160–1203. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30977-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giladi N, Tal J, Azulay T, Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Melamed E, Oertel W, Poewe WH, Stocchi F, Tolosa E (2009) Validation of the freezing of gait questionnaire in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24(5):655–661. 10.1002/mds.21745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD (1967) Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 17(5):427–442. 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Bronstein JM, Keener A, Alcazar J, Yang DD, Joshi M, Hermanowicz N (2019) PKG movement recording system use shows promise in routine clinical care of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol 10:1027. 10.3389/fneur.2019.01027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil H, Chahine L, Siddiqui J, Aldaajani Z, Bajwa JA (2020) Parkinson’s disease in the MENASA countries. Lancet Neurol 19(4):293–294. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30026-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolicheski A, Turcano P, Tamvaka N, McLean PJ, Springer W, Savica R, Ross OA (2022) Early-onset Parkinson’s disease: creating the right environment for a genetic disorder. J Parkinsons Dis 12(8):2353–2367. 10.3233/JPD-223380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SJ, Foltynie T, Blackwell AD, Robbins TW, Owen AM, Barker RA (2005) Heterogeneity of Parkinson’s disease in the early clinical stages using a data driven approach. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76(3):343–348. 10.1136/jnnp.2003.033530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor S, Churchward P, Soja K, O’Driscoll D, Braybrook M, Khodakarami H, Evans A, Farzanehfar P, Hamilton G, Horne M (2018) The use of accelerometry as a tool to measure disturbed nocturnal sleep in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 4:1. 10.1038/s41531-017-0038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metta V, Ibrahim H, Loney T, Benamer HTS, Alhawai A, Almuhairi D, Al Shamsi A, Mohan S, Rodriguez K, Mohan J, O’Sullivan M, Muralidharan N, Al Mazrooei S, Dar Mousa K, Chung-Faye G, Mrudula R, Falup-Pecurariu C, Rodriguez Bilazquez C, Matar M, Borgohain R, Chaudhuri KR (2022) First two-year observational exploratory real life clinical phenotyping, and societal impact study of Parkinson’s disease in Emiratis and expatriate population of United Arab Emirates 2019–2021: the EmPark study. J Pers Med. 10.3390/jpm12081300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metta V, Ibrahim H, Muralidharan N, Rodriguez K, Masagnay T, Mohan J, Lacsina A, Ahmed A, Benamer HTS, Chung-Faye G, Mrudula R, Falup-Pecurariu C, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Borgohain R, Goyal V, Bhattacharya K, Chaudhuri KR (2024) A 12-month prospective real-life study of opicapone efficacy and tolerability in Emirati and non-White subjects with Parkinson’s disease based in United Arab Emirates. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 131(1):25–30. 10.1007/s00702-023-02700-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisan F, Kab S, Mohamed F, Canonico M, Le Guern M, Quintin C, Carcaillon L, Nicolau J, Duport N, Singh-Manoux A, Boussac-Zarebska M, Elbaz A (2016) Parkinson disease male-to-female ratios increase with age: French nationwide study and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(9):952–957. 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Rouaud T, Grabli D, Benatru I, Remy P, Marques AR, Drapier S, Mariani LL, Roze E, Devos D, Dupont G, Bereau M, Fabbri M (2023) Overview on wearable sensors for the management of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 9(1):153. 10.1038/s41531-023-00585-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Z, Pan J, Tang S, Duan D, Yu D, Nong H, Wang Z (2021) Global trends in the incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability of Parkinson’s disease in 204 countries/territories from 1990 to 2019. Front Public Health 9:776847. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.776847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Lopez C, Sama A, Rodriguez-Martin D, Moreno-Arostegui JM, Cabestany J, Bayes A, Mestre B, Alcaine S, Quispe P, Laighin GO, Sweeney D, Quinlan LR, Counihan TJ, Browne P, Annicchiarico R, Costa A, Lewy H, Rodriguez-Molinero A (2016) Dopaminergic-induced dyskinesia assessment based on a single belt-worn accelerometer. Artif Intell Med 67:47–56. 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplawska-Domaszewicz K, Limbachiya N, Lau YH, Chaudhuri KR (2024b) Parkinson’s Kinetigraph for wearable sensor detection of clinically unrecognized early-morning Akinesia in Parkinson’s disease: a case report-based observation. Sensors (Basel). 24(10):3045. 10.3390/s24103045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplawska-Domaszewicz K, Falup-Pecurariu C, Chaudhuri KR (2024a) An Overview of a Stepped-care Approach to Modern Holistic and Subtype-driven Care for Parkinson’s Disease in the Clinic. touchneurology. https://touchneurology.com/?p=75527. 2024

- Qamar MA, Rota S, Batzu L, Subramanian I, Falup-Pecurariu C, Titova N, Metta V, Murasan L, Odin P, Padmakumar C, Kukkle PL, Borgohain R, Kandadai RM, Goyal V, Chaudhuri KR (2023) Chaudhuri’s dashboard of vitals in Parkinson’s syndrome: an unmet need underpinned by real life clinical tests. Front Neurol 14:1174698. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1174698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput AH, Rajput ML, Ferguson LW, Rajput A (2017) Baseline motor findings and Parkinson disease prognostic subtypes. Neurology 89(2):138–143. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve A, Simcox E, Turnbull D (2014) Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Res Rev 14(100):19–30. 10.1016/j.arr.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Pan C, Li Y, Li L, Hua P, Xu L, Zhang L, Zhang W, Xu P, Liu W (2021) Consistency and stability of motor subtype classifications in patients with de novo Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurosci 15:637896. 10.3389/fnins.2021.637896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Martin D, Sama A, Perez-Lopez C, Catala A, Moreno Arostegui JM, Cabestany J, Bayes A, Alcaine S, Mestre B, Prats A, Crespo MC, Counihan TJ, Browne P, Quinlan LR (2017) Home detection of freezing of gait using support vector machines through a single waist-worn triaxial accelerometer. PLoS One. 12(2):e0171764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Molinero A, Sama A, Perez-Martinez DA, Perez Lopez C, Romagosa J, Bayes A, Sanz P, Calopa M, Galvez-Barron C, de Mingo E, Rodriguez Martin D, Gonzalo N, Formiga F, Cabestany J, Catala A (2015) Validation of a portable device for mapping motor and gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 3(1):e9. 10.2196/mhealth.3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Molinero A, Sama A, Perez-Lopez C, Rodriguez-Martin D, Quinlan LR, Alcaine S, Mestre B, Quispe P, Giuliani B, Vainstein G, Browne P, Sweeney D, Moreno Arostegui JM, Bayes A, Lewy H, Costa A, Annicchiarico R, Counihan T, Laighin GO, Cabestany J (2017) Analysis of correlation between an accelerometer-based algorithm for detecting Parkinsonian gait and UPDRS subscales. Front Neurol 8:431. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Molinero A, Perez-Lopez C, Sama A, Rodriguez-Martin D, Alcaine S, Mestre B, Quispe P, Giuliani B, Vainstein G, Browne P, Sweeney D, Quinlan LR, Arostegui JMM, Bayes A, Lewy H, Costa A, Annicchiarico R, Counihan T, Laighin GO, Cabestany J (2019) Estimating dyskinesia severity in Parkinson’s disease by using a waist-worn sensor: concurrent validity study. Sci Rep 9(1):13434. 10.1038/s41598-019-49798-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safiri S, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Mousavi SE, Sullman MJM, Araj-Khodaei M, Singh K, Kolahi AA, Gharagozli K (2023) The burden of Parkinson’s disease in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health 23(1):107. 10.1186/s12889-023-15018-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sama A, Perez-Lopez C, Rodriguez-Martin D, Catala A, Moreno-Arostegui JM, Cabestany J, de Mingo E, Rodriguez-Molinero A (2017) Estimating bradykinesia severity in Parkinson’s disease by analysing gait through a waist-worn sensor. Comput Biol Med 84:114–123. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbier A, Qamar MA, Rajah T, Chaudhuri KR (2016) New concepts in the pathogenesis and presentation of Parkinson’s disease. Clin Med (Lond) 16(4):365–370. 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-4-365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed T, Sama A, Catala A, Rodriguez-Molinero A, Cabestany J (2015) Adapted step length estimators for patients with Parkinson’s disease using a lateral belt worn accelerometer. Technol Health Care 23(2):179–194. 10.3233/THC-140882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundgren M, Andreasson M, Svenningsson P, Noori RM, Johansson A (2021) Does information from the Parkinson KinetiGraph (PKG) influence the neurologist’s treatment decisions? An observational study in routine clinical care of people with Parkinson’s disease. J Pers Med 11(6):519. 10.3390/jpm11060519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wamelen DJ, Hota S, Podlewska A, Leta V, Trivedi D, Rizos A, Parry M, Chaudhuri KR (2019) Non-motor correlates of wrist-worn wearable sensor use in Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 5:22. 10.1038/s41531-019-0094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woitalla D, Mueller T, Russ H, Hock K, Haeger DA (2007) The management approaches to dyskinesia vary from country to country. Neuroepidemiology 29(3–4):163–169. 10.1159/000111578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu RL, Wu RM, Chan AY, Mok V, Wu YR, Tilley BC, Luo S, Wang L, LaPelle NR, Stebbins GT, Goetz CG (2017) Cross-cultural differences of the non-motor symptoms studied by the traditional chinese version of the international parkinson and movement disorder society- unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov Disord Clin Pract 4(1):68–77. 10.1002/mdc3.12349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirra A, Rao SC, Bestwick J, Rajalingam R, Marras C, Blauwendraat C, Mata IF, Noyce AJ (2023) Gender differences in the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 10(1):86–93. 10.1002/mdc3.13584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the EmPark-PKG study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please email vin.metta@nhs.net.