Abstract

Increasing evidence supports the role of the placenta in neurodevelopment and in the onset of neuropsychiatric disorders. Recently, mQTL and iQTL maps have proven useful in understanding relationships between SNPs and GWAS that are not captured by eQTL. In this context, we propose that part of the genetic predisposition to complex neuropsychiatric disorders acts through placental DNA methylation. We construct a public placental cis-mQTL database including 214,830 CpG sites calculated in 368 fetal placenta DNA samples from the INMA project, and run cell type-, gestational age- and sex-imQTL models. We combine these data with summary statistics of GWAS on ten neuropsychiatric disorders using summary-based Mendelian randomization and colocalization. We also evaluate the influence of identified DNA methylation sites on placental gene expression in the RICHS cohort. We find that placental cis-mQTLs are enriched in placenta-specific active chromatin regions, and establish that part of the genetic burden for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder confers risk through placental DNA methylation. The potential causality of several of the observed associations is reinforced by secondary association signals identified in conditional analyses, the involvement of cell type-imQTLs, and the correlation of identified DNA methylation sites with the expression levels of relevant genes in the placenta.

Subject terms: Epigenomics, DNA methylation, Development, Quantitative trait, Schizophrenia

Here, Cilleros-Portet et al. present a large placental methylation database as a tool to explore the genetic burden that acts in prenatal stages, giving insight into neuropsychiatric disorders, and with especial emphasis on schizophrenia.

Introduction

The impact of the intrauterine environment on development and health, both fetal and long-term, has been known for many years1. In this line, the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis postulates that perinatal and early life environments can impact fetal and later life health2. Prenatal stress affects the quality of the intrauterine environment, and is highly related to cardiovascular and metabolic, as well as behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders3. Thus, the placenta is an ephemeral fetal organ that is uniquely situated to evaluate prenatal exposures in the context of DOHaD, because it manages the transport of nutrients, oxygen, waste, and endocrine signals between mother and fetus4. Additionally, fetal genetics-mediated placental expression has been reported to have large effects on early life traits, that may persist later in life as etiologic antecedents for complex traits5. Finally, the placenta constitutes the interface between mother and child during pregnancy and is the maximum regulator of the prenatal milieu, having a key role in the growth and the neurodevelopment of the fetus6. Hence, the placenta has been described as the third brain that links the fetal brain with the mature maternal brain, thus becoming the cornerstone to understanding the prenatal environmental effects on neurodevelopment7, and potentially, on the appearance of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders later in life.

Particularly in the case of schizophrenia (SCZ), many susceptibility genes have been identified, demonstrating a remarkable genetic basis, but a considerable amount of research suggests that environmental factors may also play a role8. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of SCZ was proposed by Daniel Weinberger in 1987 and has been reinforced in the last decades, with increasing evidence of neurodevelopmental abnormalities contributing to the pathophysiology of the disease9–11. The central argument of this hypothesis states that abnormal fetal neurodevelopment creates a vulnerability to developing SCZ later in life. In fact, different pieces of evidence state that prenatal insults such as maternal immune activation (MIA) and other pregnancy and labor-related triggers such as hemorrhage, preeclampsia, birth asphyxia, and uterine rupture are associated with SCZ in offspring12,13. Specifically, MIA occurs when inflammatory markers rise above the normal range in pregnancy as a result of maternal inflammation and can be caused by psychosocial stress, infection, or other factors14.

Besides, there are many studies proposing that the intrauterine environment alters the placental function through epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation (DNAm)15. It is very important to note that, while DNAm is bimodally distributed in most tissues and cell types, it follows a trimodal distribution in the very specific case of the placenta, due to its high content of both partially methylated domains and CpG positions with intermediate methylation levels16. Although a very recent study has pointed out that DNAm of healthy donors could be highly cell type-specific, with the modest impact of either genetics or other factors17, it is worth mentioning that DNAm has been considered as a bridge between the environment and the genome that, at the same time, is under the control of both environmental and genetic factors. The peculiarity of the placenta, an ephemeral organ that connects two organisms, together with its very particular methylome that is remarkably enriched in CpG sites with intermediate methylation levels16, leads us to speculate that the genome-environment interaction and its impact on DNAm is very likely unique in the placenta and deserves further investigation.

In the past several years, different works have demonstrated that placental DNAm is sensitive to environmental factors surrounding the gestation. In 2021, the Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics (PACE) consortium conducted a meta-analysis on 1700 placental samples and found a placenta-specific DNAm signature of maternal smoking during pregnancy, with differentially methylated CpG sites located in active regions of the placental epigenome, and close to genes involved in the regulation of inflammatory activity, growth factor signaling, and response to environmental stressors18. One year later, the same consortium reported in the largest placental DNAm study conducted to date that maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index also impacts the placental methylome, specifically at CpG sites located close to obesity-related genes and altogether, enriched in oxidative stress and cancer pathways19.

Noting the impact of the genetic background on placental DNAm, several studies have reported a number of methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) in the placenta and have used them in different downstream applications20–23. Among others, Tekola-Ayele and collaborators showed candidate functional pathways that underpin the genetic regulation of birth weight via placental epigenetic and transcriptomic mechanisms22. However, the catalog of mQTLs they provided was limited to birth weight-related genomic loci. More recently, Casazza et al. reported nearly 50,000 placental cis-mQTLs and 2489 sex-specific placental cis-mQTLs23. They found out that placental mQTLs were enriched in genome-wide association study (GWAS) loci for both growth- and immune-related traits, and that male- and female-specific mQTLs were more abundant than non-sex-specific ones. Another remarkable discovery is that they found a modest enrichment of placental mQTLs in proportion to the calculated SNP heritability in the case of neuropsychiatric disorders, compared to immune- and growth-related traits. However, they did not rule out the possibility that a part of the genetic susceptibility of neuropsychiatric disorders is conferred through the modification of the placental methylome, and if this were the case, it would be relevant not only in terms of etiopathology, but also from a clinical viewpoint, due to the importance of localizing therapeutic targets in the right tissues, contexts and developmental stages.

In cross-tissue analyses, mQTLs have been highlighted as powerful instruments revealing molecular links to traits otherwise missed by expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL). In fact, recent work by Oliva et al. reported that trait-associated variants are more likely to result in detectable changes in DNAm rather than gene expression, highlighting the relevance of multi-tissue mQTL maps24. On the other hand, in 2021, cell type-interacting eQTLs were defined as proxies of cell type-specific eQTLs and were found not to be covered by standard eQTLs, while they appeared to be highly valuable for gaining a mechanistic understanding of complex trait associations25. Taken together, placenta-specific mQTLs, as well as placenta cell type-interacting mQTLs (imQTLs) can be useful tools in the search for the etiology of genetic associations. In this sense, it is of utmost importance to make this type of resource public and available to the scientific community.

Taking into consideration (i) the increasing evidence supporting the role of the placenta in neurodevelopment and potentially, in the onset of neuropsychiatric traits and disorders, (ii) the peculiarity of the placental methylome, and (iii) the potential of multi-tissue mQTL and imQTL maps to clarify the etiology of complex traits, we proposed that part of the genetic predisposition to complex neuropsychiatric disorders acts through the placental methylome. Thus, we constructed a publicly available placental cis-mQTL database calculated in 368 fetal placenta samples, investigated cell type-, gestational age (GA)- and sex-imQTLs, and integrated all these data with summary statistics of the largest GWAS on ten neuropsychiatric disorders, using summary-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) and colocalization approaches. Finally, we evaluated the functional role of the identified DNAm sites on placental gene expression. We found that placental cis-mQTLs are enriched in placental active genomic regions, and are useful to map the etiology of neuropsychiatric disorders to prenatal stages. Specifically, part of the bipolar disorder (BIP), major depressive disorder (MDD), and SCZ genetic risk could act through placental DNAm.

Results

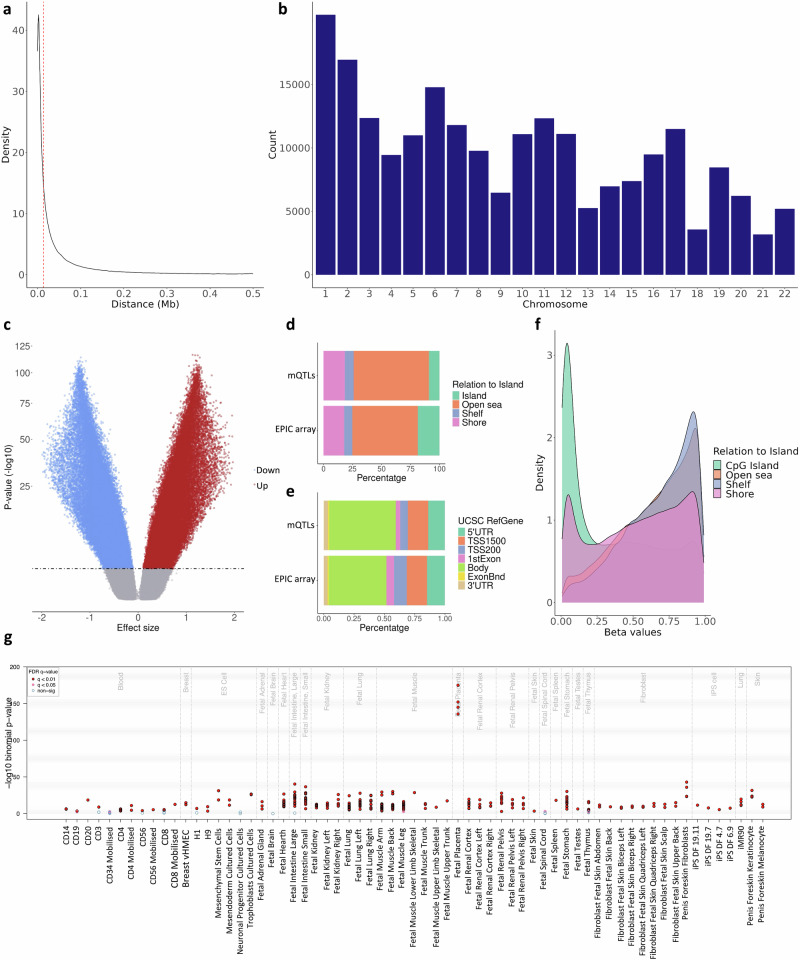

Placental cis-mQTL characterization

We discovered cis-mQTLs for 214,830 CpG sites (mSites) with False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 (permuted mQTL database) in 368 fetal placenta DNA samples from the Gipuzkoa, Sabadell, and València cohorts of the Infancia y Medio Ambiente (INMA) project26. Briefly, placental DNAm was modeled as a function of genotype in ±0.5 Mb windows, with fetal sex, five genotype principal components (PC), 18 DNAm PCs, and Planet-estimated cell types27 as covariates (See Methods section for more details). The phenotypic information of the donor mothers is summarized in Table 1. In the vast majority of the cis-mQTLs, the SNP (mVariant) and the mSite were located relatively close to each other, with a median absolute distance of 13.87 kb, indicating that genetically modulated DNAm is typically close to the implicated regulatory variant, as previously described by other authors28 (Fig. 1a). The distribution of mQTLs across chromosomes tended to be in line with chromosome length (Fig. 1b). Additionally, the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC)29 reference alleles in placental cis-mQTLs presented both positive and negative effect directions (Fig. 1c), as expected.

Table 1.

Distribution of maternal smoking during pregnancy, demographic variables, birth outcomes, and covariates of the INMA cohort

| Variable | Category | INMA (n = 368) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD or % | N missing | ||

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | Yes | 52 | 14.13% | 5 |

| No | 311 | 84.51% | ||

| Maternal age (continuous) | Mean (SD) | 368 | 30.85 ± 3.95 | 0 |

| Parity | 0 | 208 | 56.52% | 0 |

| ≥1 | 160 | 43.47% | ||

| Maternal education | Primary or without education | 68 | 18.47% | 0 |

| Secondary | 172 | 46.73% | ||

| University | 128 | 34.78% | ||

| Birth weight (g) | Mean (SD) | 368 | 3278 ± 440.55 | 0 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | Mean (SD) | 368 | 39.71 ± 1.30 | 0 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | Yes | 10 | 2.71% | 0 |

| No | 358 | 97.28% | ||

| Ancestry | White | 347 | 94.29% | 5 |

| Non-white | 16 | 4.34% | ||

| Sex of child | Female | 189 | 51.35% | 0 |

| Male | 179 | 48.64% | ||

| Socioeconomic status | I + II | 130 | 35.32% | 0 |

| III | 100 | 27.17% | ||

| IV + V | 138 | 37.50% | ||

SD standard deviation

Fig. 1. Characterization of the placental cis-mQTLs from the permuted database.

The distance between the SNP-CpG pairs participating in the reported cis-mQTLs is displayed as (a) density plot, where the X-axis represents the absolute distance in Mb. The red line represents the absolute median SNP-CpG distance. The distribution of the reported cis-mQTLs along the chromosomes is shown in the (b) barplot, where the X-axis represents the autosomal chromosomes. The distribution of the effect sizes from the reported cis-mQTLs is pictured in the (c) volcano plot, where the Y-axis illustrates the −log10 beta P-value, and the X-axis the effect size. The blue and the red dots represent the significant mQTLs below a threshold of 5 × 10−8 in the nominal database with a negative and positive effect, respectively. The distribution of the EPIC array probes and the nominal mSites considering the Relation To Island and the UCSC RefGene annotation is displayed in the (d, e) bar plots, respectively. The DNAm beta values of the participating mSites stratified by the Relation To Island annotation are shown in the (f) density plot, where the DNAm values are found on the X-axis. The eFORGE enrichment of DNase I hotspots considering the top 10,000 permuted mSites is shown in the (g) plot. The Y-axis represents the −log10 P-value of the binomial enrichment test as suggested by the eFORGE developers, and the X-axis the tissues studied. FDR-corrected q-values below 0.01 and 0.05 are represented by red and pink dots, respectively, while blue dots show q-values > 0.05.

In general, mSites were depleted from CpG islands and promoters (P < 2.2 × 10−16), and enriched within gene bodies (P < 2.2 × 10−16) and genomic features with intermediate methylation values such as open sea, and CpG island shelf and shore regions (P < 2.2 × 10−16) (Fig. 1d–f, and Supplementary Data 1). They were also enriched in the HLA region with 2896 out of the total 214,830 mSites of the permuted database (P = 1.45 × 10−10). Using eFORGE30–32, we were able to detect enrichment in DNase I hotspots and H3K4me1 broadPeaks in different tissues, the fetal placenta being the one showing the strongest signal (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2). DNase I hotspots mark accessible chromatin while H3K4me1 broadPeaks appear in enhancer regions. Afterward, we annotated the mSites to their closest genes, performed a gene-set enrichment analysis with the Disease Ontology database33, and obtained 219 enriched gene sets, including neuropathy (Benjamini-Hochberg P = 1.88 × 10−9), mood disorder (Benjamini–Hochberg P = 1.22 × 10−7), demyelinating disease (Benjamini–Hochberg P = 2.48 × 10−6), and BIP (Benjamini–Hochberg = 6.96 × 10−6) (Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Apart from the permuted cis-mQTLs, in which correction for multiple correlated variants is performed via a beta approximation, nominal and conditional cis-mQTLs were also calculated in our 368 placenta DNA samples. Briefly, the nominal cis-mQTL approach reports all the SNP-CpG combinations while the conditional method uses the permuted QTLs to perform a stepwise regression procedure and map conditionally independent cis-QTLs (see “Methods” for more details). The three complete placental cis-mQTL databases are publicly available online at the following address: https://irlab.shinyapps.io/shiny_mqtl_placenta/.

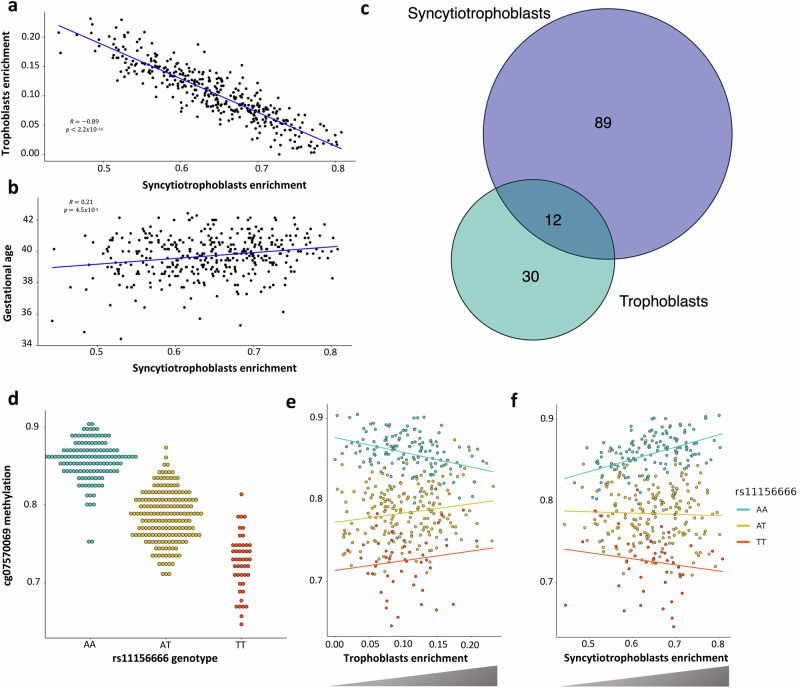

Placental cell type-, gestational age- and sex-imQTLs

The most abundant cells in the fetal placenta are syncytiotrophoblasts (STB). During gestation, undifferentiated trophoblasts (TB) change into fully differentiated STB, a continuous, multinucleated, and specialized layer of epithelial cells34. We estimated the cell type proportions of our samples with the reference-based method Planet27. As expected, the estimated content of STB in our placental samples was negatively correlated with the estimated proportion of TB (P < 2.2 × 10−16, R = -0.89) and positively correlated with gestational age (GA) (P = 4.5 × 10−5, R = 0.21) (Fig. 2a, b). We used the interaction modality of TensorQTL with the eigenMT35,36 correction to calculate STB-, TB- and GA-imQTLs, as proxies for STB-, TB- and GA-specific cis-mQTLs, and obtained 38 and 1 STB- and TB-imQTLs, respectively, with no significant GA-imQTL at a significance threshold of eigenMT FDR = 0.05 (Supplementary Data 4). The higher amount of STB-imQTLs revealed a higher statistical power for the most abundant cell type, as previously pointed out by Kim-Hellmuth et al. 25.

Fig. 2. STB- and TB-imQTLs.

The Pearson correlation between STB and TB cell types (N = 368) is shown in (a), the X-axis representing the STB proportion in the sample set, and the Y-axis showing the estimated TB proportion. The Pearson correlation between STB and GA (N = 368) is shown in (b), the X-axis representing the STB proportion in the sample set, and the Y-axis showing the GA. The intersection between STB- and TB-imQTLs is represented in the (c) Venn diagram. The standard cg07570069-rs7150262 mQTL, as well as the TB- and STB-imQTLs, are displayed in the (d–f) dot plots, respectively. In all three, the Y-axes represent the cg07570069 DNAm beta values, ranging from 0 to 1. In d the X-axis displays the genotype of rs7150262, while in (e, f), the X-axes show the TB and STB proportions, respectively. The P-values of the (i)mQTLs were the following: Pnominal = 1365 × 10−97, eigenMT FDR = 2.362 × 10−2, and eigenMT FDR = 1.579 × 10−4 for the standard mQTL, and the TB- and STB-imQTLs, respectively, obtained by linear regression calculations in TensorQTL.

The only significant TB-imQTL was also a STB-imQTL. We also estimated sharing between STB- and TB- imQTLs with Storey’s pi1 method37. Briefly, we took the eigenMT FDR < 0.05 STB-imQTLs and calculated pi1 in the nominal P-values of these SNP-CpG pairs in the unfiltered TB- and GA-imQTL sets. STB-TB sharing was estimated to be 0.68, while STB-GA sharing resulted in a pi1 = 0.51 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Beyond the global estimated sharing between cell types, and as STB and TB proportions are negatively correlated in term placentas, we wanted to know whether the genotype-cell type interaction had opposite effect directions in the overlapping imQTLs. Due to the limited number of eigenMT-significant imQTLs, we retrieved the unique interacting mSites (imSites) for each one of the two cell types analyzed, as well as for GA, with Pnominal < 5 × 10−8. We found an overlap of 12 imSites between the two cell types, and no overlap between STB- and GA-imSites (Fig. 2c). For each of the cell type-overlapping imSites, we considered the top TB-imQTL, and we calculated the correlation between their interaction effect sizes and the effect sizes reported for those same imQTLs in the STB-imQTL set. As a result, and despite the limited number of points in the regression, we obtained a highly significant negative correlation (P = 4.1 × 10−10 and R = −0.99), as in the example in Fig. 2d–f. Of note, the imQTL in Fig. 2 is the only eigenMT-significant TB-imQTL (FDR = 0.05). The moderate sharing between STB- and GA-imQTLs revealed by Storey’s pi1 suggests that the effect of GA on the genetic regulation of placental DNAm is at least partially independent of the cell type composition of each sample and therefore, rather a matter of time of gestation regardless of the TB to STB transition. Finally, as placental DNAm could differ between sexes, we also mapped sex-imQTLs but obtained no significant imQTLs after eigenMT FDR adjustment.

Multi-omics approaches to unravel the placental origin of neuropsychiatric traits and disorders

We selected the largest GWAS available for each of the following traits: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)38, aggressive behavior in children (AGR)39, autism spectrum disorder (ASD)40, BIP41, internalizing problems (INT)42, MDD43, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)44, panic disorder (PD)45, suicidal attempt (SA)46, and SCZ47 (Table 2). Most of the studies were carried out in the context of either the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC)48 or the Early Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE)49 consortium. GWAS sample sizes ranged from 6183 in the case of SA and 500,199 samples in MDD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of the neuropsychiatric traits and disorders included in this study

| Trait | Abbreviation | PubMed ID | N | N cases | N controls | Original N of SNPs | GWAS significant loci | N SMR hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | ADHD | 30478444 | 55,374 | 20,183 | 35,191 | 8,094,094 | 12 | 1 |

| Aggression | AGR | 26087016 | 18,988 | 2,188,528 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Autism spectrum disorder | ASD | 30804558 | 46,351 | 18,382 | 27,969 | 9,112,386 | 3 | 1 |

| Bipolar disorder | BIP | 34002096 | 413,466 | 41,917 | 371,549 | 7,608,183 | 64 | 30 |

| Internalizing problems | INT | 35378236 | 64,561 | 5,445,594 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Major depression disorder | MDD | 30718901 | 500,199 | 170,756 | 329,443 | 8,483,301 | 101 | 28 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | OCD | 28761083 | 9725 | 2688 | 7037 | 8,409,517 | 0 | 0 |

| Panic disorder | PD | 31712720 | 10,240 | 2,248 | 7992 | 10,151,624 | 0 | 0 |

| Suicidal attempt | SA | 34737426 | 6183 | 3288 | 2895 | 11,823,118 | 0 | 0 |

| Schizophrenia | SCZ | 35396580 | 320,404 | 76,755 | 243,649 | 7,583,660 | 287 | 214 |

We searched for placenta DNAm sites pleiotropically associated with neuropsychiatric disorders using the SMR and the heterogeneity in dependent instruments (HEIDI) tests included in the SMR software50. Briefly, SMR was originally developed to test for pleiotropic association between the expression level of a gene (or the methylation level of a CpG site) and a complex trait of interest using summary-level data from GWAS and QTL studies. We used the summary statistics of the aforementioned GWAS and the nominal placental cis-mQTL database filtered by Pnominal < 5 × 10−8, as suggested by the developers of SMR. Importantly, all 130,736 mSites considered for SMR were FDR significant in the permuted database. No significant hits were found for many of the traits, such as OCD or SA. In turn, SMR hits (Bonferroni PSMR < 0.05 and PHEIDI > 0.05) were identified for ADHD (n = 1), ASD (n = 1), BIP (n = 30), MDD (n = 28), and particularly SCZ (n = 214) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 5). Five hits were common to BIP and SCZ, with the same effect direction. Additionally, most of these hits did not overlap with CpGs reported to change as a function of GA51, suggesting relative stability in the DNAm levels during pregnancy.

Fig. 3. Manhattan plot of BIP, MDD, and SCZ GWAS highlighting the SMR and coloc results.

The original GWAS from BIP, MDD, and SCZ were plotted in the (a–c) Manhattan plots, respectively. In the Y-axes the original −log10 P-values are displayed with the genome-wide suggestive association threshold of 1 × 10−5 depicted as a dashed line, while chromosomes are shown in the X-axis. The blue dots represent genomic regions significantly colocalizing (PP4 > 0.8) with our placental mQTLs, and the red dots are mVariants associated with CpGs that have been shown to pleiotropically associate with either BIP, MDD, or SCZ in the SMR approach (Bonferroni PSMR < 0.05 and PHEIDI > 0.05). Therefore, the blue dots represent the colocalization results, and the red dots show the SMR results.

To replicate the pleiotropic associations identified in the SMR analyses, we performed a colocalization test with the same data. The Bayesian colocalization analysis implemented in the coloc R package52 focuses on finding the intersection between significant loci independently associated with two phenotypes, comparing the association patterns in the GWAS and QTL analyses across genomic regions, and thus combining the summary statistics into posterior probabilities (PP) for five hypotheses (see Methods for more information). Colocalization was performed across 64, 102, and 287 genomic regions defined in the GWAS associated with BIP, MDD, and SCZ, respectively. Regarding mQTLs, from the total amount of 214,830 mSites with FDR < 0.05 in the permuted database, 12,228, 10,343, and 38,412 mSites were considered for BIP, MDD, and SCZ colocalization analyses, respectively. In BIP, the posterior probabilities for 47 regions, involving 280 DNAm sites in 307 region-CpG pairs, were supportive of a colocalization signal (PP4 > 0.8) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 6). In MDD, the posterior probabilities for 55 regions, involving 246 DNAm sites in 253 region-CpG pairs, were supportive of a colocalization signal (PP4 > 0.8) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Data 6). Finally, in SCZ, the posterior probabilities for 161 regions, involving 865 DNAm sites in 916 region-CpG pairs, were supportive of a colocalization signal (PP4 > 0.8) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Data 6). When the overlap with SMR hits was assessed, out of the 30 SMR hits in BIP, 15 DNAm sites (50%) showed evidence of colocalization with BIP; in MDD, 11 DNAm sites (39.28%) out of the 28 SMR hits showed evidence of colocalization; and from the 214 SMR hits in SCZ, 62 DNAm sites (28.91%) colocalized with SCZ.

To provide more insights into the functional relevance of our findings, we examined the association between placental DNAm and placental gene expression in the CpGs from the SMR and colocalization analyses. We interrogated expression quantitative trait methylation sites (eQTMs) from an independent set of 195 fetal placenta samples from the Rhode Island Child Health (RICHS) study53. Briefly, eQTMs were calculated using linear models in MatrixEQTL54, adjusted by fetal sex, 5 gene expression PCs, and Planet-estimated cell types, considering all the genes in a 0.5 Mb window up and downstream of each CpG. Out of the 28 and 214 SMR-significant DNAm sites in MDD and SCZ, we found that 3 and 43 correlated with the expression levels of 4 and 26 significant eQTM-genes (FDR < 0.05), respectively, supporting the placental function of the CpGs identified in the overlap between the two analyses (Supplementary Data 7 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Interestingly, out of the 26 eQTM-genes related to SCZ, 10 mapped to the HLA region, and among these, 6 were correlated with DNAm levels of more than one CpG, with 91 significant combinations between 6 and 21 unique genes and CpG sites, respectively. In particular, the expression levels of both TOB2P1 and ZKSCAN4 were correlated with the DNAm of 21 and 18 CpG sites pleiotropically associated with SCZ, respectively, confirming the high complexity of the locus. Outside the HLA region, two eQTM-genes correlated with the DNAm levels of more than one CpG site, namely SFMBT1 and VPS37B (Supplementary Fig. 5). Specifically, the expression of SFMBT1 on chromosome 3 was correlated with DNAm at four different contiguous loci that were independently identified in the SMR approach, while VPS37B on chromosome 12 correlated with the DNAm levels of two different CpG sites, with the same associated top SNP in SMR. In conclusion, our results suggest some regional pleiotropy, also outside the complex HLA region, that could have a functional impact on the placental expression landscape.

Next, we identified the intersection between SMR, colocalization, and eQTM results for each trait (Supplementary Fig. 4). In the case of MDD, one placental DNAm site colocalized with a MDD-associated genomic locus on chromosome 14, and DNAm levels correlated with the placental expression of LRFN5. In SCZ, 6 placental DNAm sites colocalized with 6 SCZ-associated loci on chromosomes 6, 7, 8, 11, 19, and 22, with DNAm levels that correlated with the placental expression of 6 nearby genes (GLB1L3, LETM2, NAGA, PSMG3, SLC6A16, and ZSCAN12) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The overlapping hit in MDD was cg10318063 (Bonferroni PSMR = 0.003) that colocalized with the MDD-associated locus on chr14:41940872-42476274 (PP4 = 0.976) (Fig. 4). The DNAm levels of this CpG correlated with the expression of LRFN5 in placenta (FDR = 1.23 × 10−13 and R = 0.539). Remarkably, several SNPs in LRFN5 have been found to be pleiotropically associated with both MDD and chronic pain, although the effector tissue or cell type has not been fully established55. On the other hand, it is also known that this gene is expressed in TB stem cells, and therefore could play a role in placenta56. Finally, the CpG identified is located in the promoter region of LRFN5. Altogether, these results suggest that the reported association is potentially causal, rather than pleiotropic.

Fig. 4. A CpG pleiotropically associated with MDD.

The mVariant rs1950835, highlighted as a purple diamond, with the −og10 P-values of the original MDD GWAS and the placental mQTLs, is represented in the (a) locusZoom plot. The X-axis displays the involved genomic region of chromosome 14 in Mb, showing the distribution of the coding genes in the locus, as well as the location of the cg10318063 mSite (PP4 = 0.976 in the colocalization test). The Y-axis shows the −log10 P-value from the original GWAS and placental mQTLs, and the SNPs are color-coded as a function of the LD with the highlighted SNP considering the 1000G reference panel. The mQTL, rs1950835-cg10318063 (Pnominal = 2.446 × 10−34 of the linear regression in TensorQTL) is plotted in the (b) dotplot, where the Y-axis represents the beta DNAm values of the mSite, ranging from 0 to 1. The X-axis displays the genotype of the mVariant. The eQTM of cg10318063 is portrayed in the (c) dotplot, where the X-axis represents the DNAm values of the CpG involved, ranging from 0 to 1. The Y-axis displays the expression values of the LRFN5 gene in the placenta. The hypothesis of the pleiotropical association between the SNP, the DNAm values of the CpG in the placenta, and the gene expression levels of LRFN5 in the placenta and MDD are schematically represented in (d). The vertical pleiotropy (or causal association) hypothesis is represented with a blue background, and the horizontal pleiotropy hypothesis is highlighted with a yellow background.

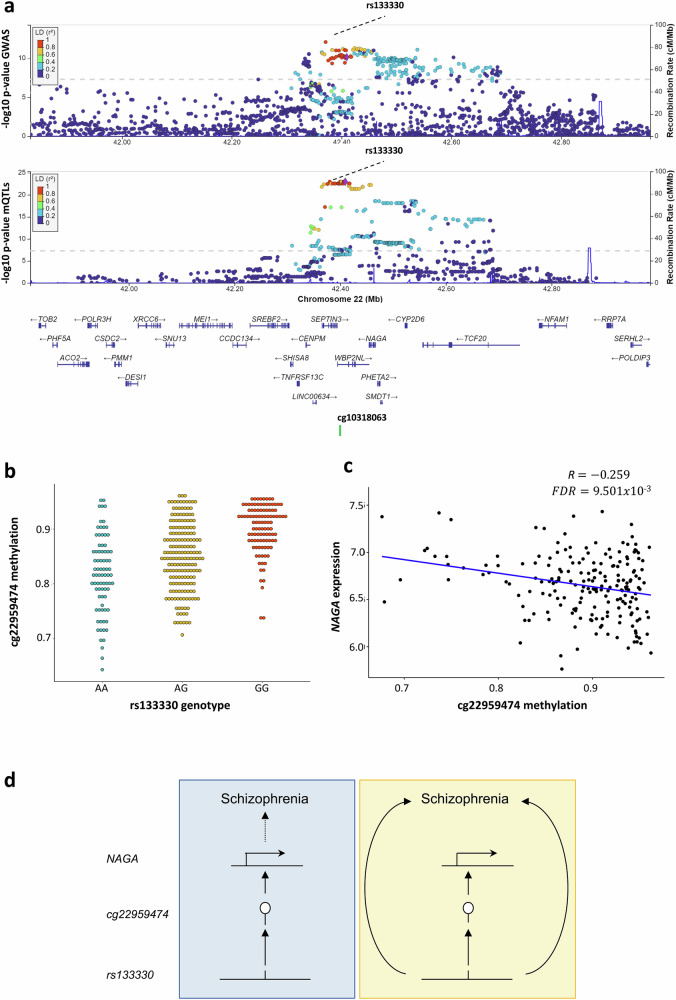

Among the CpGs found in SCZ, cg22959474 was pleiotropically associated with the disorder (Bonferroni PSMR = 8.741 × 10−3), colocalized with the GWAS peak on chr22:41024556: 42765301 (PP4 = 0.881), and DNAm levels of the CpG were correlated with the placental expression of NAGA (FDR = 9.501 × 10−3 and R = −0.259) (Fig. 5). Interestingly, this gene is known to regulate important neurodevelopmental processes, including the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells57. In this context, it has been described that NAGA confers susceptibility to SCZ by modulating dendritic spine density58. It is well known that these structures, located on the dendritic branches of neurons, are important for neural connectivity and plasticity, and that abnormalities in their formation and elimination can lead to neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and SCZ58. This would support the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of SCZ11.

Fig. 5. A CpG pleiotropically associated with SCZ.

The mVariant rs133330, highlighted as a purple diamond, with the −log10 P-values of the original SCZ GWAS and the placental mQTLs, is represented in the (a) locusZoom plot. The X-axis displays the involved genomic region of chromosome 22 in Mb, showing the distribution of the coding genes in the locus, as well as the location of the cg22950474 mSite (PP4 = 0.901 in the colocalization test). The Y-axis shows the −log10 P-value from the original GWAS and placental mQTLs, and the SNPs are color-coded as a function of the LD with the highlighted SNP considering the 1000 G reference panel. The mQTL, rs133330-cg22950474 (Pnominal = 1.871 × 10−10 of the linear regression in TensorQTL) is plotted in the (b) dotplot, where the Y-axis represents the beta DNAm values of the mSite, ranging from 0 to 1. The X-axis displays the genotype of the mVariant. The eQTM of cg22950474 is portrayed in the (c) dotplot, where the X-axis represents the DNAm values of the CpG involved, ranging from 0 to 1. The Y-axis displays the expression values of the NAGA gene in the placenta. The hypothesis of the pleiotropical association between the SNP, the DNAm values of the CpG in the placenta, the gene expression levels of NAGA in the placenta, and SCZ are schematically represented in (d). The vertical pleiotropy (or causal association) hypothesis is represented with a blue background, and the horizontal pleiotropy hypothesis is highlighted with a yellow background.

Finally, we performed a Reactome gene-set analysis59 of the 26 genes at the intersection between the SMR and eQTM results in SCZ. We observed enrichment for 101 gene sets (Supplementary Data 8), including many epigenetic regulatory pathways, such as different histone modifications, DNAm, and chromatin condensation and organization, suggesting that SCZ risk alleles could change the epigenetic landscape of placenta through the regulation of epigenetic modifiers. Additionally, we observed a remarkable enrichment in immune-related pathways such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection and overall viral infection, reinforcing the idea of MIA as a link between the placenta and SCZ risk.

Conditional SMR analysis of placental cis-mQTLs, BIP, MDD, and SCZ

The developers of the SMR software designed the HEIDI test assuming that a single causal variant in the cis-mQTL region affects both DNAm and the trait analyzed50. Under the assumption of pleiotropy, when there are multiple causal variants in a region, the pleiotropic signal of one causal variant will be diluted by that of other non-pleiotropic causal variants. We therefore performed a GCTA conditional analysis60 conditioning for the top associated cis-mQTL in both the GWAS and mQTL data sets. In those cases where a secondary signal was pinpointed by the presence of heterogeneity (PHEIDI < 0.05) in the cis-mQTL region, in either the GWAS or the mQTL dataset, we performed another round of conditional analyses conditioning only on the secondary signal in both the GWAS and mQTL datasets, and then reran the SMR and HEIDI test at the top cis-mQTL using the estimates of SNP effects from the conditional analyses. We applied this approach to those CpGs that passed the SMR test but failed to pass the HEIDI test. Nevertheless, due to power constraints, only those CpGs with suggestive support for an association with both traits according to coloc (PP3 + PP4 > 0.9) were considered.

We discovered a secondary hit in SCZ, in which two independently associated SNPs, i.e., rs880638 (the primary signal) and rs1233572 (the secondary signal) had a pleiotropic effect on both cg27314558 and SCZ (Bonferroni PSMR = 0.015 and PSMR = 0.024, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Data 5 and 9). Even though we did not find any significant eQTM for this CpG, located in the HLA region, we have to take into account that small RNAs were not included in the eQTM analysis. Having a closer look at this genomic region using the UCSC web browser61, we found that cg27314558 is surrounded by multiple aminoacyl-transfer RNAs (tRNA), an alanine tRNA (TRA-AGC6-1) being the closest (Supplementary Fig. 7). In this context, it is well known that impaired placental amino acid transfer is associated with fetal growth restriction62. Additionally, a recent study revealed that placentas of preterm births show a significant negative correlation with alanine concentration63. Our results, namely the presence of two independent signals pointing to a single DNAm site in the placenta that, moreover, is close to multiple aminoacyl-tRNAs, suggest a causal association of the CpG site with SCZ.

SMR analysis of placental cell type-, GA- and sex-imQTLs in BIP, MDD, and SCZ

We filtered the imQTLs by Pnominal < 5 × 10−8, as suggested by the developers of SMR. Then we classified the cell type-imQTLs as positive or negative according to Kim-Hellmuth et al., with the aim of retrieving potentially cell type-specific mQTLs (that is, positive imQTLs) rather than those that more likely reflect interactions with another cell population that is decreasing (that is, negative imQTLs). In summary, positive imQTLs show an increase of the main genotype effect from low to high cell proportions, i.e., the mQTL effect size increases with the cell type abundance. Meanwhile, negative imQTLs show a decrease in the mQTL effect size as a function of the cell type proportion.

We used SMR to combine positive imQTLs with the BIP, MDD, and SCZ GWAS, and obtained one STB-imQTL (related to BIP), and two TB-imQTLs (one each in BIP and MDD) (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Data 10). We found an imQTL involving rs11637580 and cg27130493 (Fig. 6) in which cg27130493 appeared to be associated with BIP and changed its DNAm levels as a function of TB proportion, in an rs11637580 genotype-dependent manner (Bonferroni PSMR = 0.015). This CpG is located in the gene body of SMAD3. The overexpression of this gene in the placenta has been described to activate the ability of TB to form endothelial-like networks, while its defect has been associated with pre-eclampsia64. Additionally, it is a well-known target for lithium treatment in BIP65. Interestingly, rs11637580 is not directly associated with BIP in the original GWAS, suggesting a possible causal association between placental DNAm and BIP at this CpG site.

Fig. 6. TB-imQTL pleiotropically associated with BIP.

The imVariant rs11637580, highlighted as a purple diamond, is shown in the original BIP GWAS in the (a) locusZoom plot. The X-axis displays the involved genomic region in chromosome 15 in Mb, showing the distribution of the coding genes in the locus, as well as the location of the imSite cg27130493. The Y-axis shows the −log10 P-value from the original GWAS, and the SNPs are color-coded as a function of LD with the highlighted SNP considering the 1000 G reference panel. The TB-imQTL (Pnominal = 1.671 × 10−8 of the linear regression in TensorQTL) is pictured in the (b) dotplot. The X-axis represents the cg27130493 DNAm beta values and the Y-axis the TB proportion, both ranging from 0 to 1. The genotype of the rs11637580 imVariant is color-coded as indicated in the legend.

Comparison with SMR results for brain mQTLs

In order to ascertain the tissue specificity of our findings, we also performed the same SMR analyses with fetal brain and brain cis-mQTLs in BIP, MDD, and SCZ. The fetal brain cis-mQTL database was published by Hannon et al. in ref. 66. Briefly, mQTLs were calculated in 166 human fetal brain samples (56-166 days post-conception). The DNAm data were obtained with the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation 450 K array, and mQTL mapping was performed with the MatrixEQTL R package54, considering a cis-window of ±0.05 Mb. Only mQTLs with a P < 1.5 × 10−9 were made available, resulting in 556,513 fetal brain cis-mQTLs that were downloaded from the SMR portal. The second brain cis-mQTL database was originally from a 2018 publication by Qi et al. 67, in which cis-mQTLs from three different datasets were meta-analyzed: 468 brain cortical region samples from the ROSMAP study68, 166 fetal brain samples from the study by Hannon et al. 66, and 526 frontal cortex region samples69 were included, amounting to a final sample size of 1,160 brain samples and nearly 6 M cis-mQTLs. As in the case of the fetal brain mQTL database, this dataset was downloaded from the SMR data portal.

In BIP we obtained 13 and 35 significant SMR hits (Bonferroni PSMR < 0.05 and PHEIDI > 0.05) in the fetal brain and brain mQTL datasets, respectively (Supplementary Data 11), and with the same criteria, we obtained 10 and 23 SMR hits in MDD, and 50 and 188 in SCZ. As shown in Fig. 7, the trait with the largest overlap of pleiotropically associated DNAm sites among tissues is SCZ, although the overlap is very limited in all the traits, also at the level of mVariants (Supplementary Fig. 9). In the case of the fetal brain database, the smaller sample size limits the number of detected mQTLs and could lead to underestimating the proportion of the genetic risk that acts through the fetal brain. When we compared our most reliable hits in the placenta (intersection among SMR, coloc, and eQTM results) with the brain SMR results, neither MDD nor SCZ presented any overlapping DNAm sites.

Fig. 7. Overlap between the SMR results in brain, placenta, and fetal brain, in BIP, MDD, and SCZ.

The overlap between the mSites pleiotropically associated between the three tissues and BIP, MDD, and SCZ are represented in the (a–c) Venn diagrams, respectively. Overlapping mSites are shown, and also the closest gene from the Illumina annotation file (between brackets).

Discussion

In this study, we have constructed different placental cis-mQTL databases with 368 placenta samples from the INMA project. Importantly, we have made all results publicly available both in their raw formats and by means of a user-friendly, shiny-based browser that enables to search for the mQTLs of interest by CpG, SNP, and/or genomic coordinates. We believe that this tool will be useful to the scientific community. In general, the placental cis-mQTLs were depleted in regions that are usually hypomethylated, such as promoters and CpG islands, very likely because lower and more stable DNAm values will hardly correlate with the genotype or any other variable. In turn, an enrichment of intermediate DNAm values was observed, usually present in CpG island shelves and shores, as well as in open sea regions. The genotype-regulated placental DNAm seems highly placenta-specific and interestingly, is enriched in placenta-specific active chromatin marks, and in pathways such as neuropathy, mood disorders, and BIP, among others. This, together with the fact that mQTLs have recently been highlighted as powerful instruments to reveal molecular links to traits otherwise missed by eQTL-GWAS colocalization approaches24, encouraged us to conduct a multi-omics study to try to unveil the placental contribution to the developmental origins of different neuropsychiatric disorders.

Kim-Hellmuth et al. showed that cell type-interacting eQTLs (ieQTLs) are enriched in GWAS signals and can improve GWAS-eQTL matching for the mechanistic understanding of those loci25. In this context, we wondered whether this could also be true for placental mQTLs and calculated STB- and TB-imQTLs. STB were considered for several reasons, (1) they are the most abundant cell type in term placenta70, (2) they cover the entire surface of the villous trees in the placenta, and thus are in direct contact with maternal blood34, (3) they orchestrate the complex biomolecular interactions between the fetus and the mother, and (4) they act as an important endocrine organ, producing numerous growth factors and hormones that support and regulate placental and fetal development and growth71–74. Given that TB are STB progenitor cells, and that there is a very strong negative correlation between the proportions of the two cell types in our samples, we decided to calculate TB-imQTLs as well. We observed higher statistical power for the most abundant cell type and therefore, a larger amount of STB-imQTLs compared to TB-imQTLs. However, there was a remarkable sharing and, as expected, the allelic effects in the overlapping imQTLs were negatively correlated between the two cell types. As TB is known to differentiate into STB throughout gestation34, and STB content in term placenta is positively correlated with GA at birth, we wanted to know whether cell type-imQTLs are equivalent to GA-imQTLs. This was not the case, revealing that TB-to-STB differentiation has a notable effect on placental DNAm that is not explained by GA.

Remarkably, placental DNAm is pleiotropically associated with BIP, MDD, and in particular with SCZ, while it seems to barely associate with early onset conditions such as ADHD and ASD. These results could arise from the sample sizes and power constraints of the GWAS available, as well as from the higher heritability of certain disorders, including BIP and SCZ. However, it is important to note that a recent article found that MDD shows a very high polygenicity compared to other psychiatric disorders; that is, more genetic variants with weaker effects contribute to the overall genetic signal in MDD, and make the trait less annotable75. In contrast, ADHD, BIP, and SCZ showed the highest discoverability and hence a more annotable genetic signal. Subsequently, the estimated sample size required to reach 90% SNP heritability was more than eight times larger for MDD than for ADHD, BIP, and SCZ. Therefore, the moderate signal in ADHD and even more remarkably, the presence of a considerable pleiotropy between placental DNAm and MDD, suggest that our findings are guided not only by the strength and annotability of the genetic basis of the diseases studied, but rather by a genuine association with placental DNAm. In addition, it is well known that BIP, MDD, and SCZ share a common genetic background and therefore, it is plausible that part of the genetic risk could act through common processes at the same developmental stages76.

However, we wanted to make sure that our SMR results were not merely led by statistical power. Therefore, on the one hand, we calculated the correlation between the SMR hits and (i) the GWAS sample size, (ii) the total number of SNPs per GWAS, and (iii) the number of GWAS-significant loci, in all the neuropsychiatric disorders studied. We observed a correlation of R = 0.48 between the number of significant SMR results and the GWAS sample size, although it did not reach statistical significance, probably due to the limited number of SMR experiments performed (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 10A). On the other hand, even though the total number of SNPs included in each of the GWAS was not correlated at all with the results obtained in SMR, there was a highly significant correlation between the latter and the number of significant loci reported in each GWAS (P < 1.7 × 10−6, r = 0.97) (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 10B, C). This is intuitively logical since the higher the number of genomic regions with disease-associated SNPs, the more likely it will be to find an overlap with SNPs associated with placental DNAm or with anything else. Anyway, it is worth mentioning that SCZ is by far the disorder showing the highest ratio between SMR hits and associated GWAS loci, suggesting that placental methylome may be particularly relevant for this disorder. Additionally, we ran the same SMR approach with two previous, smaller SCZ GWAS and still obtained significant SMR hits, with a remarkable overlap among the three studies. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 10D, together with the Venn diagrams showing the overlapping results (Supplementary Fig. 10E, F). In summary, our results reveal an at least moderate correlation between the number of SMR hits and the GWAS sample size, which is surpassed by far by the number of GWAS significant loci, with a vast effect on the capacity of SMR to find potentially interesting results. Nevertheless, the abundant results in SCZ are not fully explained by this effect.

It is possible to gain insight into the pathogenesis of complex disorders by defining the environmental, biological, and temporal context in which genes increase disease susceptibility. In 2018, Ursini et al. discovered that when early life complications are present, the polygenic risk score (PRS)-explained risk of SCZ is more than five times higher than when they are absent77. SCZ loci that interact with early life complications are not only highly expressed in the placenta, but also differentially expressed between complicated and normal pregnancies and enriched in response-to-stress pathways. Remarkably, three out of the genes whose expression correlates with DNAm sites associated with SCZ according to the different approaches presented here, were among the 248 placenta-enriched SCZ genes described by Ursini (i.e., NAGA, PSMG3, and SFMBT1). Of note, among these, NAGA has been described to confer SCZ risk by modulating the dendritic spine density in neurodevelopment58. Altogether, we propose that these genes could not only mediate SCZ risk through placental expression, but rather through DNAm-regulated placental expression patterns.

More recently, the placenta-specific SCZ-PRS has also been shown to interact with both brain volume and cognitive function, suggesting particular neurodevelopmental trajectories in the path toward SCZ78. Especially in this work, Ursini and colleagues also studied the enrichment in the placenta of genes involved in the risk of other neuropsychiatric disorders, and the relationship between neurodevelopmental outcomes and placenta-specific PRS for the same disorders. BIP presented a very high enrichment in genes that are expressed in the placenta, although its placenta-specific PRS did not interact with either brain volume nor cognition. The placental enrichment observed in BIP makes sense since SCZ and BIP present the highest genetic correlation compared to any other pair of psychiatric traits79. This is in line with the convergence between the CpGs associated with both BIP and SCZ found in this study. Nevertheless, there are remarkable differences in outcome between the two disorders, and SCZ patients have been described to be more prone to suffer from severe cognitive impairment than BIP patients80. In conclusion, placental DNAm could be important in BIP although through trajectories that are different from those characterized by Ursini and colleagues in SCZ. In any case, we believe that our findings support a hypothesis according to which placental DNAm could translate both the genetic basis and the environmental milieu into fetal genetic programs that could eventually result in impaired neurodevelopmental trajectories leading to SCZ, and maybe, also to other neuropsychiatric disorders. This hypothesis will need to be tested with additional research.

Regarding the genes affected by placental DNAm pleiotropically associated with SCZ according to SMR, we want to highlight that they were enriched mostly in epigenetic regulation pathways and immune-related terms, including HCMV infection and late events, as well as assembly of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) virion, among others. On the one hand, the multiple epigenetic pathways involved suggest that SCZ risk alleles could cause deep epigenetic changes in the placenta as a result of DNAm modifications in close proximity to the histone-coding genes H2BC6 and H3C4. These genes have been previously related to recurrent spontaneous abortion and neurulation, respectively57,58. On the other hand, those histones, together with VPS37B, were some of the most relevant genes contributing to the enrichment of immune-related biological routes. This reinforces the idea of MIA being implicated in the neurodevelopmental origins of SCZ. Particularly for HCMV, it has been reported that the DNAm state of the host genome can make cells more or less prone to infection, and that histones participate in this process because, although HCMV is devoid of these proteins, it captures them from the host for the chromatinization of its own genome81. Moreover, it is known that congenital HCMV infection can cause long-term clinical manifestations such as hearing loss, neurodevelopmental disorders, ophthalmic complications, and ASD, among others82. The virus moves from mother to fetus by infecting TB in the placenta, altering the development and integrity of the organ, and eventually, inhibiting placental cell differentiation, self-renewal, and migration. Last but not least, in a very recent transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) by Ursini and colleagues, the placental genes and transcripts associated with SCZ risk were shown to be enriched for pathways related to the activation of the pathogenesis of both Coronavirus and influenza, further reinforcing the idea of the implication of viral infections83.

Altogether, environmental insults that occur in pregnancy and early life, including maternal infections, are hypothesized to program the immune and developmental epigenetic code in the fetus, thereby influencing the risk of suffering from neurodevelopmental disorders later in life84–86. The MIA hypothesis proposes that exposure to a dysregulated maternal immune milieu in utero affects fetal neurodevelopment87,88. Moreover, in humans, maternal factors implicated in MIA are associated with epigenetic modifications in the placenta89,90. The placenta plays a pivotal role in maintaining immune homeostasis in the maternal-fetal interface. However, when a sustained placental inflammatory response occurs due to maternal environmental factors, the offspring can suffer from developmental abnormalities91.

Apart from the genes leading the aforementioned pathway enrichments, several others are also worthy of mention, as noted by their correlation with multiple CpG sites associated with SCZ. On the one hand, among the genes in the HLA region and despite the high complexity of the locus, TOB2P1 is the one locally correlated with more SCZ-associated DNAm sites. Additionally, its RNA expression level in the placenta is regulated by the genotype of nearby SNPs92. On the other hand, outside the HLA region, we would like to mention SFMBT1 and VPS37B. The former is an epigenetic regulator that is crucial for TB maintenance and placental development93,94. Moreover, it was one of the 139 placenta and SCZ-specific risk genes prioritized in the TWAS by Ursini and colleagues83, and it is near a CpG identified by our group to be associated with pre-pregnancy maternal body mass index19. The relevance of VPS37B is beyond any doubt given its immune function and its involvement in viral infection. In conclusion, all those genes deserve further investigation.

Taken individually, the genes that are most likely to be causally involved in the different neuropsychiatric disorders studied were LRFN5 in MDD, and NAGA in SCZ. In the case of LRFN5, several variants in this gene have been found to be pleiotropically associated with both MDD and chronic pain55. Additionally, it is well known that LRFN5 is involved in brain cell communication and is located in a large and complex genomic niche that is highly conserved in mammals95. The specific locus structure of this region increases ASD susceptibility in males. In the case of NAGA, in 2021, Li and colleagues reinforced the hypothesis of the neurodevelopmental origins of SCZ by demonstrating that this gene modulates the dendritic spine density, a process with a pivotal role in cognitive function, learning, and memory58. Deficits in dendritic spines could produce alterations in the neuronal circuitry within and across multiple brain regions. More precisely, lower spine density has been observed in the neocortex of SCZ patients96. Interestingly, in the context of pregnancy, gestational stress leads to significant changes in spine density and dendritic complexity in the prefrontal cortex, located within the neocortex. These effects have been reported to occur in the offspring of stressed mothers, in a sex-specific manner97.

The placental DNAm sites that resulted from the SMR analyses confronting the BIP, MDD, and SCZ GWAS, and the STB- and TB-imQTLs are also worthy of mention. For example, we found that cg27130493 is pleiotropically associated with BIP while it changes its methylation levels as a function of TB proportion, in a rs11637580 genotype-dependent manner. This CpG is located in the gene body of SMAD3, a gene with singular functions in the placenta and also in BIP itself 64,65. Additionally, this SNP is not directly associated with BIP, increasing the likelihood of causality rather than pleiotropy. The most important limitation of this part of the study is the lack of placental cell type-specific expression data to ascertain whether cg27130493 and other DNAm sites identified in this approach are correlated with the expression of nearby genes in the placenta, in a cell type-specific manner. However, the fact that the CpG sites change not only depending on the genotype of adjacent SNPs, but also as a function of estimated placental cell proportions, increases the probability of the placenta being the effector organ of those genetic associations.

Lastly, we tried to ascertain the tissue-specificity of our findings by comparing placenta SMR hits to those from two brain cis-mQTL databases. We found a limited overlap among the tissues, suggesting that the majority of our pleiotropically associated DNAm sites could be relatively specific to the placenta (or at least, not related to brain DNAm). However, it is important to consider that although the SMR approach was executed exactly in the same manner for the three databases, these were quite different from each other. In particular, the fetal brain database was calculated in a limited number of fetal brain samples, in SNP-CpG windows ten times smaller than the ones we used (0.05 Mb vs 0.5 Mb), and DNAm was measured with the Infinium HumanMethylation 450 K array (with approximately half the probes in the Infinium HumanMethylation EPIC array used in the present study), therefore resulting in half a million cis-mQTLs compared to the more than 9 million mQTLs that were included in the SMR analysis in our case. This suggests a more limited mapping potential with the fetal brain mQTL database and thus, a possible underestimation of the fetal brain DNAm that is really involved in the disorders studied.

The main limitation of our study is that, as pointed out by Ursini et al. in relation to their own work78, the considerable overlap in cell biology between the brain and placenta does not allow to exclude the possibility that part of the pleiotropy observed here is related to a more direct effect in the brain exerted by the same DNAm sites as observed in the placenta. However, we believe that the different pieces of evidence, including the intersection with the placental eQTMs and even the presence of secondary signals, support that a part of the genetic risk of suffering from BIP, MDD and very especially SCZ, could act through placental DNAm at specific genomic loci. Another limitation is that different methylation beadchips have been employed in the INMA and RICHS cohorts, and thus, we are probably underestimating the effects of DNAm over placental gene expression. Finally, at this point, we lack direct experimental support for our results. Further research, especially regarding in vitro validation of the most likely causal candidates, would enormously help supplement our findings.

In conclusion, we find placental cis-mQTLs to be highly placenta-specific, with a remarkable enrichment in genomic regions active in placenta and neurodevelopment- and mental health-related pathways. We prove that they are useful to map the etiologic window of neuropsychiatric disorders to prenatal stages and conclude that part of the genetic risk of BIP, MDD, and in particular SCZ, act through placental DNAm at specific genomic loci. In fact, some of the observed associations might be causal rather than pleiotropic due to the presence of secondary association signals in conditional analyses, involvement of cell type-specific imQTLs, and association with the expression levels of relevant genes in the placenta. It is of particular interest that SCZ-associated placental DNAm correlates with the expression of immune- and neurodevelopment-related genes in the placenta, providing further support to the hypothesis of the neurodevelopmental origins of SCZ. Future work, including functional approaches such as in vitro modulation of expression in potential effector cell lines, as well as long-term follow-up in prospective studies, will be needed in order to better characterize our findings and their implication in disease development.

Methods

Ethics

All cohorts obtained ethics approval and informed consent from participants prior to data collection through their Institutional Ethics Boards, in accordance to the criteria set by the Declaration of Helsinki. This particular study did not involve the acquisition of new data and therefore, did not require additional approval by the Ethics Board.

Placental biopsies and DNA extraction

In the INMA26 project, 2506 mother-fetus pairs were followed until birth, and a selection of 397 placentas were collected, representing the three geographical areas involved in the study. Collected placentas were stored at −80 °C in a central biobank until processing. Biopsies of approximately 5 cm3 were obtained from the inner region of the placenta, approximately 1.0–1.5 cm below the fetal membranes, corresponding to the villous parenchyma, and at a distance of ~5 cm from the site of cord insertion. 25 mg of placental tissue was used for DNA extraction, previously rinsed twice for 5 min in 0.8 mL of 0.5X PBS in order to remove traces of maternal blood. Genomic DNA from the placenta was isolated using the DNAeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA). DNA quality was evaluated on a NanoDrop spectrophotomer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and additionally, 100 ng of DNA was run on 1.3% agarose gels to confirm that samples did not present visual signs of degradation. Isolated genomic DNA was stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Genotype data

Genome-wide genotyping was performed using the Illumina GSA Beadchip at the Human Genotyping Facility (HuGeF), Dept Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and the Spanish National Genotyping Center, CEGEN, Madrid, Spain. Genotype calling was done using the GeneTrain2.0 algorithm based on HapMap clusters implemented in the GenomeStudio software. Samples were genotyped in four batches.

The quality control of the genotype data from 397 INMA samples and 509,450 genetic variants was performed using the PLINK 1.9 software following the standard recommendations98–100. All plink files were initially processed with Will Rayner’s preparation Perl script available from Mark McCarthy’s Group as recommended in the documentation from the Michigan Imputation Server101, using the HRC r1.1 2016 reference panel29. Variants with a call rate below 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1%, or a P-value from the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) exact test below 1 × 10−6 were removed. Samples with discordant sex, those with average heterozygosity values above or below 4 standard deviations, or with more than 3% missing genotype were filtered out. Identity-by-descent values were calculated with PLINK, and from those sample pairs that showed PI-HAT estimates above 0.18, the sample with a higher proportion of missing genotypes was removed.

The final dataset was imputed with the Michigan Imputation Server using the HRC reference panel, Version r.1.1 2016. Before imputation, data was converted into VCF format. Phasing of haplotypes was done with Eagle v2.4102 and genotype imputation with Minimac4103, both implemented in the code by the Michigan Imputation Server. Finally, we removed variants with an imputation quality r2 below 0.9, a MAF lower than 5%, a HWE P-value below 0.05, and more than two alleles, to avoid SNPs with few or no individuals bearing the minor allele homozygous genotype in our sample set. Only those samples with paired DNAm data were considered in this analysis. The final dataset consisted of 368 samples and 4,171,035 SNPs.

DNA methylation data

DNAm was assessed with the Infinium Methylation EPIC BeadChip from Illumina, following the manufacturer’s protocol in the Erasmus Medical Center core facility. Briefly, 750 ng of DNA from 397 placental samples were bisulfite-converted using the EZ 96-DNA methylation kit from Zymo Research, following the manufacturer’s standard protocol, and DNAm was measured using the Infinium protocol. Three technical duplicates were included. Samples were randomized taking into account region-of-origin and sex. As the number of samples in each condition was different, a perfect randomization was not possible. However, all the plates had samples from all three geographical areas involved, and an equilibrated number of male and female samples.

The quality control of the DNAm data, including 865,859 DNAm probes, was performed using the PACEAnalysis R package (v.0.1.7)104. Before the quality control with PACEAnalysis, one sample was discarded because of too many missing values in relevant variables. With the R package, we discarded those samples with a call rate below 95%, sex inconsistencies, intentioned or non-intentioned duplicates, and those contaminated with DNA from another subject or the mother. Only those samples with paired genotype data were considered in this study. Probes with a call rate lower than 95%, in the sex chromosomes, with SNPs (European MAF ≥ 5%) and cross-hybridizing potential were excluded from the analysis105.

The methylation beta values were normalized in different steps. Dye-bias and Noob background correction, implemented in the minfi R package, were applied106,107, followed by normalization of the data with the functional normalization method108. Then, to correct for the bias of type-2 probe values, the beta-mixture quantile (BMIQ) normalization was applied109. After that, we explored the clustering of the data through Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and tested the association of the 12 first PCs with the main and the technical variables. Array batch effect was controlled with the ComBat method110. To correct for the possible outliers, we Winsorized the extreme values to the 1% percentile (0.5% on each side), where percentiles were estimated with the empirical beta distribution. Finally, the rank-based inverse normal transformation (RNT) was applied to the beta values, and these estimations were the DNAm values considered for mQTL mapping. The final dataset consisted of 368 samples and 747,486 DNAm probes (CpGs).

Cell type proportions of six populations (STB, TB, nucleated red blood cells, Hofbauer cells, endothelial cells, and stromal cells) were estimated from DNAm using the placenta reference panel from the 3rd trimester implemented in the Planet R package27.

Placental cis-mQTL analysis

A total of 4,171,035 SNPs and 747,486 CpGs from 368 samples with paired genotype and DNAm data were considered for the cis-mQTL analysis in TensorQTL111. TensorQTL nominal modality performs linear regressions between the genotype and the normalized DNAm RNT values, as implemented in FastQTL112. The covariates included in the regression model were the sex of the fetuses, the first five PCs derived from the genotype data (genotype PCs), the first 18 non-genetic DNAm PCs, and the cell type proportions calculated with the Planet methylation panel. Genotype and DNAm PCs were included in the model as covariates to remove hidden and/or technical confounders affecting the DNAm data. To avoid multicollinearity between the non-genetic DNAm PCs and the other covariates, the DNAm PCs were calculated on the residuals from a multiple linear regression adjusting the normalized DNAm RNT-values by the known covariates (sex of the fetuses, the first five genotype PCs, and the five estimated cell types). Following Min et al., we kept all DNAm PCs that cumulatively explained 80% of the variance with a maximum number of 20 PCs for subsequent steps28. Then we performed a GWAS on each of the DNAm PCs and retained those PCs that were not associated with the genotype at a suggestive threshold (P > 1 × 10−7). This procedure returned 18 non-genetic DNAm PCs.

The TensorQTL cis-region was specified as ±0.5 Mb from each tested CpG position, consistent with the results of previous studies where the distance between the majority of the cis-mVariants and the mSites was ≤ 0.5 Mb66,113–115. In the final nominal cis-mQTL database, we included only those probes with at least one cis-mQTL at Pnominal < 5 × 10−8. This same regression model was used to build two additional cis-mQTL databases; permuted and conditional. The permuted cis-mQTL database consists of correcting for multiple correlated variants tested via a beta approximation which models the permutation outcome with a beta distribution as described in Ongen et al. 2016112. This database was presented as the main database and characterized accordingly, but the nominal was used for some downstream analyses. In turn, the conditional database uses the permuted QTLs to perform a stepwise regression procedure to map conditionally independent cis-QTLs as described by the GTEx Consortium116.

Characterization of placental cis-mQTLs

As previously mentioned, the characterization of the cis-mQTLs was performed on the permuted database in different steps. First, we plotted the distribution of both the distance between each mSite and mVariant pair, and the mQTLs along the chromosomes, followed by a volcano plot to check the distribution of the negative and positive effect sizes.

Second, using the annotation from IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b4.hg19 R package117, we performed several chi-square tests to assess the enrichment and depletion of the UCSC RefGene and Relation to CpG Island annotations. We also depicted density plots of the DNAm values according to the Relation to CpG Island annotation. Moreover, for the top 10,000 mSites, we assessed enrichment and depletion of overlap with tissue-specific and cell type-specific regulatory features including DNase I hypersensitivity sites (DHS), all 15-state chromatin marks, and all five H3 histone marks (i.e., H3K27me3, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3) from consolidated ROADMAP Epigenomics Mapping Consortium118 using eFORGE v2.030–32. The enrichment and depletion with each of the three putative functional elements were tested separately and compared to the respective data from the consolidated ROADMAP epigenomics reference panel. Briefly, we selected only the top 10,000 probes following the advice of the developers of eFORGE to avoid saturating the background bins, especially those related to CpG Island annotation categories that may be more limited, taking into consideration the total amount of probes per category in the Illumina EPIC array.

Lastly, over-representation analyses of Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets were conducted with MissMethyl R package119–122. MissMethyl performs a hypergeometric test taking into account the bias derived from the differing number of probes per gene and the multiple genes annotated per CpG122. Gene set enrichment analyses with the Disease Ontology (DO) database were conducted with the DOSE R package123. With DOSE, we performed the gene set enrichment analysis considering the genes annotated in the IllumuminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b4.hg19 R package117 as background.

Placental cis-imQTL analysis

The cell type-imQTLs were computed with the interaction modality in TensorQTL, consisting of nominal associations for a linear model that includes a genotype per interaction term111. Additionally, we used the run_eigenmt = True option, to compute eigenMT-adjusted P-values. This method runs faster than permutations, calculates adjusted P-values that closely approximate empirical ones35, and thus, has been implemented by TensorQTL as an alternative to permutation in imQTL mapping. The same SNPs, CpGs, and samples from the permuted database (without interaction terms) were considered for the interaction analyses. The covariates used were the sex of the fetuses, the first five genotype PCs, and 18 DNAm PCs. Following the recommendations by Kim-Hellmuth et al. 202125, estimations of STBs and TBs per sample were defined separately as the interaction terms. We considered significant only those imQTLs that showed an eigenMT FDR < 0.05.

We estimated sharing between STB- and TB-imQTLs with Storey’s pi1 method36. Briefly, we took the eigenMT FDR < 0.05 STB-imQTLs and retrieved the nominal P-values of these SNP-CpG pairs from the TB-imQTL set. Then we used the qvalue package124 to estimate pi1 (the proportion of true positives). As STB and TB proportions are negatively correlated in term placentas, we wanted to know whether the interaction effect sizes of the overlapping imQTLs were also negatively correlated. Therefore, we retrieved the imSites with a Pnominal < 5 × 10−8 in STB- and TB-imQTLs to draw a Venn diagram. Finally, with this list of imSites, we calculated the correlation of the interaction effect sizes of the overlapping imQTLs considering only the top imVariant from the TB-imQTLs database.

Additionally, both GA and sex were also considered as interaction terms. In the first case, the covariates included were the sex of the fetuses, the first five genotype PCs, the 18 DNAm PCs and the cell type proportions from Planet. In the second case, the covariates included were the first five genotype PCs, the 18 DNAm PCs and the cell type proportions from Planet. For sharing calculations, the same methods as with TB were used for GA.

Genome-wide association studies

The GWAS summary-statistics used in this analysis were the public largest to date association studies of ADHD38, AGR39, ASD40, BIP41, INT42, MDD43, OCD44, PD45, SA46, and SCZ47 from EAGLE, Indonesia Schizophrenia Consortium, International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC), OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS), PsychENCODE, Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium, UK Biobank (UKB), SynGO Consortium, and 23andMe, among others.

GWAS summary statistics were harmonized to dbSNP build 155 with the INMA genotype data as a reference. The harmonization steps included: changing rsID to chromosome:position nomenclatures, correcting the effect allele, the effect size, and the allele frequency according to the reference genotypes if applicable, and creating a .ma format file with the summary-statistics as indicated in the SMR pipeline50. All locusZoom plots were constructed as suggested on their web page (http://locuszoom.org/), using the LD panel of 1000G125.

Multi-SNP-based Mendelian randomization analysis

Mendelian Randomization analysis was carried out considering cis-mQTL SNPs as the instrumental variables (IVs), CpG methylation as the exposure (X), and the neuropsychiatric traits as the outcome (Y). Multi-SNP-based MR (SMR-multi)126 analysis was performed by the SMR software50. SMR integrates GWAS and QTL summary statistics to test for pleiotropic associations between quantitative traits, such as methylation or expression, and a complex trait, for instance, a disease. More precisely, SMR-multi includes multiple SNPs at a cis-mQTL locus in the SMR test to calculate the causative effect of an exposure on an outcome (bxy). First, SMR-multi selected all SNPs with Pnominal < 5 × 10−8 in the cis region (±0.5 Mb of the CpG). Second, it removed SNPs in very high LD with the top associated SNP (LD r2 > 0.9). Then, the causative effect (bxy) from the exposure on the outcome was estimated at each of the SNPs and combined in a single test using an approximate set-based test accounting for LD among SNPs126. Additionally, the HEIDI test was performed. HEIDI uses multiple SNPs in a cis-mQTL region to distinguish pleiotropy from linkage. As it is described by Zhu et al. 50, under the hypothesis of pleiotropy, where DNAm and a trait share the same causal variant, the bxy values calculated for any SNPs in LD with the causal variant are identical. Therefore, testing against the null hypothesis that there is a single causal variant is equivalent to testing whether there is heterogeneity in the bxy values estimated for the SNPs in the cis-mQTL region. For each DNAm probe that passed the genome-wide significance (Pnominal < 5 × 10−8) threshold for the SMR test, HEIDI tested the heterogeneity in the bxy values estimated for multiple SNPs in the cis-mQTL region. In this analysis, significant pleiotropic associations between DNAm and neuropsychiatric diseases were selected as those with PSMR-corrected Bonferroni < 0.05 and PHEIDI > 0.05 (not showing heterogeneity).

In the two interaction cis-mQTL databases used for SMR, we included probes with at least one cis-imQTL at Pnominal < 5 × 10−8. The imQTLs obtained from each model were categorized as positively and negatively correlated with cell type estimates, or as uncertain if this was ambiguous, following Kim Hellmuth et al. 202125. To categorize the imQTLs into these groups, genotype main effects at low (<25th percentile) vs high (>75th percentile) cell type proportions were compared. imQTLs with positive cell type correlation showed an increase of the main genotype effect from low to high cell proportions ( low < high). imQTLs with negative cell type correlation showed a decrease ( low > high) and the uncertain group contained imQTLs for which the sign flipped between low and high cell type proportions ( low ≠ high).

Colocalization analyses

Recalling the definition of cis-mQTLs in our analysis, all mSites with FDR < 0.05 and located within ±0.5 Mb of the regions defined in the original neuropsychiatric GWAS were tested. Colocalization analysis was performed to identify the overlap between causal mQTLs and GWAS-significant loci, as described in Giambartolomei et al. 2014, with the R coloc package52. In total 12,228, 10,343, and 38,412 mSites were tested for BIP (n = 63 autosomal regions), MDD (n = 98 autosomal regions), and SCZ (n = 279 autosomal regions), respectively. Because data for all SNPs (regardless of significance) are required for this analysis, first, the mQTL analysis was rerun for these mSites so that all association statistics could be recorded for all mVariants within ±0.5 Mb of the DNAm site. Then, we retrieved the regression coefficients, their variances, and the SNP minor allele frequencies from the original GWAS data and our mQTLs, and the prior probabilities were left as their default values. This methodology quantifies the support across the results of each GWAS for five hypotheses by calculating the posterior probabilities, denoted as PPi for hypothesis Hi.

H0: there exist no causal variants for either trait;

H1: there exists a causal variant for one trait only, GWAS;

H2: there exists a causal variant for one trait only, DNAm;

H3: there exist two distinct causal variants, one for each trait;

H4: there exists a single causal variant common to both traits.

Conditional analyses