Abstract

Objective

Psychological trauma negatively impacts maternal and infant health during the perinatal period. A history of traumatic experiences related to previous pregnancies and births (termed pregnancy-specific psychological trauma or PSPT) increases the risk of a host of psychological disorders. It can impede women's/the pregnant individual's relationship with the healthcare system and their developing child. There are, however, no guidelines or agreed-upon validated screening measures to assess PSPT during the perinatal period. To build a knowledge base to develop future measure(s) of PSPT, we conducted a systematic review to understand how and when PSPT has been measured during pregnancy.

Data sources

Searches were run in July 2021 on the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE 1946 to Present), Ovid EMBASE (1974 to present), Scopus, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Cochrane. Updated searches and reference searching/snow-balling were conducted in September 2023.

Study eligibility criteria

The search strategy included all appropriate controlled vocabulary and keywords for psychological trauma and pregnancy.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Two independent researchers screened abstracts and, subsequently, full-texts of abstracts for appropriateness, with conflicts resolved via a third independent reviewer. A secondary analysis was performed on studies measuring PSPT during pregnancy.

Results

Of the 576 studies examining psychological trauma in pregnancy, only 15.8% (n=91) had a measure of PSPT. Of these 91 studies, 53 used a measure designed by the research team to assess PSPT. Critically, none of the measurements used screened for PSPT comprehensively.

Conclusion

It is time to screen for and study PSPT in all perinatal individuals. Recognition of PSPT should promote trauma-informed care delivery by obstetrics and neonatology/pediatric teams during the perinatal period.

Key words: perinatal, pregnancy, pregnancy complications, pregnancy loss, psychological trauma, traumatic delivery

Introduction

The perinatal period is a medically and psychologically vulnerable time, with increased rates of medical and psychiatric complications.1,2 Despite tremendous progress in the fields of obstetrics and neonatology leading to improved maternal and infant outcomes over the past several decades, the rates of adverse pregnancy and childbirth outcomes remain high.3, 4, 5 Medical and psychiatric complications during the perinatal period have a two-generational impact, not only affecting the woman's/pregnant individual's health but also setting the stage for the health trajectory of the infant and the broader family system. For instance, pregnancy complications increase the rates of childbirth complications, including eclampsia, cardiomyopathy, sepsis, and infant respiratory distress.6, 7, 8 Aside from these medical complications, given their associated increased health costs, adverse maternal and infant health outcomes add burdens to the healthcare system, including economic considerations.9, 10, 11 Nevertheless, pregnancy and early childhood are periods with increased contact with the medical system, and perinatal interventions have a greater reach and potential to benefit parents and their offspring.1 Therefore, screening, early identification, and assessment of risk and vulnerability factors, coupled with timely intervention strategies, are critical to enhancing maternal and infant perinatal health outcomes.

Psychologically traumatic exposures are prevalent and associated with increased rates of psychiatric, metabolic, and autoimmune disorders, with cumulative early adversity and trauma exposure leading to shorter life expectancy.9,12 Similar to the general population, psychologically traumatic exposures have been associated with worse perinatal outcomes for women.13 For instance, a history of childhood adversity and maltreatment has been associated with increased rates of adverse pregnancy and childbirth outcomes.14,15 Similarly, experiences of domestic violence have been associated with worse prenatal care and adverse birth outcomes.16, 17, 18 Finally, a history of cumulative trauma has been associated with an increased risk of premature birth.19 The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends all obstetricians-gynecologists should implement universal screening to assess for a history of psychological trauma.20

Following the detection of psychological trauma in a pregnant patient, ACOG advises obstetric practices to adopt a trauma-informed care approach, avoid stigmatization, and prioritize resilience. Trauma-informed care relies on the following principles: (1) realizing the widespread impact of trauma and potential paths to recovery; (2) recognizing the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and the healthcare team; (3) responding by fully integrating this knowledge into practice, policies, and procedures; and d) active resistance to retraumatizing the person.21 Histories of psychological trauma continue to be underreported and underrecognized,22 creating barriers to implementing trauma-informed care. Therefore, there is an urgent need for obstetric practices to have protocols for universal screening of psychological trauma to offset the detrimental health outcomes associated with psychological trauma during pregnancy.

An understudied yet clinically significant category of psychological trauma that can have a profound medical and psychiatric impact on the course of pregnancy is a group of traumatic events directly related to pregnancy and childbirth. We propose the term pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT) to describe these events. PSPT is highly prevalent and includes several important but distinct categories of traumatic experiences, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Types of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT) and examples of what these types of PSPT capture

| Type of traumatic experiences |

|---|

| Fear of childbirth |

| Fear of birth |

| Medically complicated pregnancy for women/the pregnant person |

| History of infertility |

| Obstetric complications |

| Pregnancy complication |

| Bleeding during pregnancy |

| Medically complicated pregnancy for infant |

| Premature birth |

| Diagnosis of fetal anomaly |

| Low birthweight babies |

| Medically complicated pregnancy not specified |

| General assessment of pregnancy complications |

| Pregnancy loss |

| History of reproductive loss, including miscarriage, stillbirth, fetal or neonatal deaths, abortion (including elective and spontaneous abortion) |

| Traumatic birth |

| Traumatic birth |

| Emergency C-sections |

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

PSPT is prevalent, though rates vary regionally. A notable portion of pregnancies end in miscarriage (10%–20%), and many women face stillbirth (1 in 72 births globally)23,24 or neonatal death (estimated to be 2.3 million in 2022),25 give birth prematurely (10.4% of US births in 2022, and 4% to 16% globally in 2020),26,27 experience traumatic birth (up to 45%),28 experience fear of childbirth as a form of anticipatory traumatic experience (6.3 to 14.8%),29,30 or undergo a multitude of other pregnancy complications. PSPT can profoundly impact the health and well-being of parents and their developing child across the perinatal period. For instance, a history of perinatal loss leads to increased rates of mood and anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), difficulties with parenting, and replacement or vulnerable child syndrome (replacement child syndrome describes when the subsequent child replaces the feelings of loss or the lost child in parent's mind, and vulnerable child syndrome describes exaggerated parental perceptions of medical, behavioral, and developmental vulnerability in the child) in subsequent pregnancies and children.13,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Premature birth has been associated with higher rates of psychological distress for parents and psychological, medical, and developmental complications for the child.37, 38, 39, 40 Perinatal loss or premature birth increases the risk of mood and anxiety disorders in future pregnancies.41,42 Traumatic birth can influence future family planning decisions (longer time between pregnancies, fewer births) and lead to a significant fear of childbirth in subsequent pregnancies.29,43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48

In current clinical practice, some aspects of PSPT are captured by the obstetric history obtained in the first prenatal visit. However, obstetric history is typically taken using a medical lens rather than a psychological lens, which limits the translation of this history to trauma-informed prenatal care and appropriate treatment of active mood disorders, anxiety, and PTSD. Furthermore, some forms of PSPT have historically been disenfranchised and dismissed, such as first-trimester miscarriages, as compared to later fetal demise, which is more routinely recognized as traumatic. This presents a disconnect between prenatal and childbirth experiences and complications perceived as traumatic by patients but not necessarily viewed as traumatic by their obstetrics providers. Trauma is in the eye of the beholder49 and the traumatic nature of an exposure should, therefore, be based on the subjective perceptions of the person experiencing it. Furthermore, cultural and regional norms and beliefs might play a role in how and what is considered traumatic throughout the perinatal period. Therefore, there is a critical need for a neutral and more comprehensive screening that explores all potential psychologically traumatic experiences related to pregnancy and childbirth. To understand the extent to which PSPT has been examined in the literature, if there are regional variations in studying PSPT, and whether a comprehensive PSPT screening measure exists and how it is utilized, we conducted a secondary analysis of a larger systematic review of the assessment of psychological trauma in the prenatal period50 by analyzing the studies assessing PSPT in pregnancy. Informed by current clinical practice and pregnancy and birth outcomes literature, it was hypothesized that PSPT is not systematically screened during pregnancy, and there are no widely used validated screening measures that 1) explore a broad range of PSPT, and 2) probe women's/the pregnant individual's subjective impression of those experiences.

Objectives

Following a systematic review of the assessment of psychological trauma during pregnancy, a secondary analysis was conducted to examine the number of studies specifically measuring PSPT, including the measurements and methods used to assess PSPT, the timing of assessment of PSPT, and the global representation of the evaluation of PSPT.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) guidelines51 and the protocol is registered in the ‘International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews’ (PROSPERO),52 with the identification number CRD42022384173. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of literature review

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy

A medical librarian performed comprehensive systematic searches to identify studies addressing the measurement of psychological trauma during pregnancy. Searches were run in July 2021 on the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE 1946 to Present), Ovid EMBASE (1974 to present), Scopus, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Cochrane. Updated searches and reference searching/snow-balling were conducted in September 2023. The search strategy included all appropriate controlled vocabulary and keywords for psychological trauma and pregnancy. Full details regarding the search strategy are available on Open Science Framework (osf.io/356av/). There were no language or publication date restrictions in the search.

Study selection

Two independent researchers screened the appropriateness of each abstract, and conflicts were resolved via consensus. Following this, the full text of the abstracts deemed appropriate were screened for inclusion by two independent researchers, and again, conflicts were resolved via consensus. The screening was conducted using Covidence.53

Data extraction

The research team reviewed the full text of included studies to obtain the pertinent data. At the stage of data extraction, data obtained from each article was checked independently by two researchers. At the final stage and before data analysis, the data for studies assessing PSPT during pregnancy were separated and rechecked independently by two researchers for accuracy. In both phases, conflicts were resolved via consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias

This systematic review examines the methodology used to assess PSPT and does not pertain to study outcomes. Since outcomes are not synthesized here, no assessment of the risk of bias was performed.

Data analysis

Following data extraction, data were cleaned and categorized for uniformity. We began by categorizing types of psychological trauma. To do so, all measures used in all studies were examined. We reviewed all probes on each measure to discern what kind of trauma each question was measuring. Studies were categorized as measuring pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT) if they probed the history of infertility, miscarriage, spontaneous or elective abortion, stillbirth, infertility, fear of childbirth, premature birth, emergency cesarean section, low birth weight, fetal anomaly, or pregnancy or obstetric complications. Other trauma types not reported here included childhood abuse, childhood adversity, crime/violence exposure, environmental trauma, healthcare trauma, general trauma history, and interpersonal trauma.

To further explore the nature of PSPT, different types of PSPT were categorized into six categories: fear of childbirth, medically complicated pregnancy for women/the pregnant individual, medically complicated pregnancy for the infant, medically complicated pregnancy not specified, pregnancy loss, and traumatic birth (Table 1).

Next, the format of trauma measures was examined. Trauma measures were considered previously published measurements if they had been used in more than one study and the measure was published. These measurements, though not always validated or standardized, are often more scrutinized and tested. Measures were considered “in-house” if the research team developed them or were single item questions on trauma history. Variations among the in-house measures and the type of trauma they measured, in addition to incomplete descriptions of the in-house measures in most papers, precluded any analysis to compare similarities and differences between these measures.

The time of measurement during pregnancy was also assessed. For ease of interpretation, measurement time was categorized as first trimester for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people less than 13 weeks gestation (range or mean), second trimester for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people between 13 and 28 weeks gestation (range or mean), third trimester for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people later than 28 weeks gestation (range or mean), first or second trimester for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people at any point in the first or second trimester (range from 0 to 28 weeks), second or third trimester for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people at any point in the second or third trimester (range from 29 to 41 weeks), any point in pregnancy or nonspecific for studies measuring trauma in women/pregnant people at any point in pregnancy or the authors did not specify a time, or multiple points in pregnancy for longitudinal assessments of trauma in pregnancy.

Lastly, the geographical representation of studies measuring PSPT was examined across geopolitical regions: Asia, Central America, Europe, the Middle East or Northern Africa, North America, Oceania, South America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies were categorized into each region based on the country where the study was conducted.

The frequency of each outcome measure was assessed using SPSS.

Results

Of the identified 576 studies examining trauma in pregnancy, only 15.8% (n=91) had a measure of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT), with the vast majority of studies, 84.2% (n=485), incorporating no measure of PSPT. Full details regarding these 91 studies are available on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/29b4m). Of those studies examining PSPT, 4.0% (n=23) assessed PSPT only, and 11.8% (n=68) examined both PSPT and nonpregnancy-related trauma (eg, interpersonal trauma, childhood trauma) (Figure 2). Of the 91 studies, only 12% (n=11) assessed PTSD symptoms or diagnosis (n=5 PTSD Checklist, n=3 PTSD Symptom Scale, n=2 Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders, n=2 Traumatic Events Scale, n=1 Trauma Symptoms Checklist).

Figure 2.

Percentages of studies assessing only pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT), only nonpregnancy-specific psychological trauma, and both PSPT and nonpregnancy-specific psychological trauma

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

The types of PSPT assessed varied across studies (Table 2). The majority (86%) of studies measured pregnancy loss.

Table 2.

Type of traumatic experiences

| Type of traumatic experiences | Frequency of assessment (number of studies) |

|---|---|

| Fear of childbirth | 11.0% (n=10) |

| Medically complicated pregnancy for women/the pregnant person | 16.5% (n=15) |

| Medically complicated pregnancy for infant | 11.0% (n=10) |

| Medically complicated pregnancy not specified | 4.4% (n=4) |

| Pregnancy loss | 84.6% (n=77) |

| Traumatic birth | 5.5% (n=5) |

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

Most of the 91 studies assessing PSPT utilized in-house measures (58.2%, n=53). Other measures assessing PSPT are listed in Tables 3A and B.

Table 3a.

Name of PSPT measures

| Name of measure | Frequency of use (Number of studies) |

|---|---|

| In-house measure | 58.2% (n=53) |

| Life Stressor Checklist54 | 24.2% (n=22) |

| Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire55 | 6.6% (n=6) |

| Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire56 | 4.4% (n=4) |

| WHO Multicountry Study on Women's Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire57 | 4.4% (n=4) |

| Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health58 | 1.1% (n=1) |

| Life Event Scale for Pregnant Women59 | 1.1% (n=1) |

| Life Events and Difficulties Schedule60 | 1.1% (n=1) |

| Life Events Questionnaire61 | 1.1% (n=1) |

| Ontario Perinatal Record62 | 1.1% (n=1) |

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

Table 3b.

Categories of PSPT included in each measure

| Measure | Type of PSPT |

|---|---|

| Life Stressor Checklist | Pregnancy loss, Medically complicated pregnancy for infant |

| Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire | Fear of childbirth |

| Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire | Pregnancy loss |

| WHO Multicountry Study on Women's Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire | Pregnancy loss |

| Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health1 | Fear of childbirth, Medically complicated pregnancy for women/pregnant person, Medically complicated pregnancy for infant, Medically complicated pregnancy not specified, Pregnancy loss, Traumatic birth |

| Life Event Scale for Pregnant Women2 | Pregnancy loss |

| Life Events and Difficulties Schedule3 | Pregnancy loss |

| Life Events Questionnaire | Pregnancy loss |

| Ontario Perinatal Record | Medically complicated pregnancy for women/pregnant person, Medically complicated pregnancy for infant |

Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health is currently replaced by the Stafford Interview (the 6th edition of the Birmingham Interview). The PSPT categories in this table are reported based on the Stafford Interview.63

Despite reaching out to the authors, we could not review the contents of the Life Event Scale for Pregnant Women. The category of pregnancy loss is included based on what is reported in the paper.59

Life Events and Difficulties Schedule64 was translated and adapted to be used with the childbearing population and, based on the study report, probed for stillbirth and miscarriage.60

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

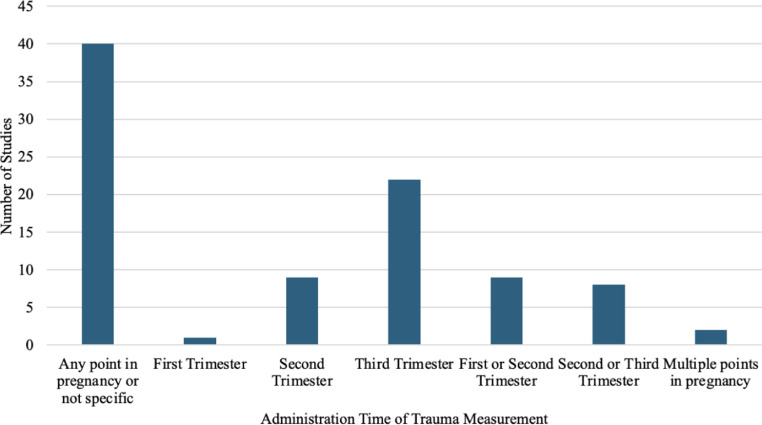

The administration timing of PSPT measures in pregnancy also varied. The majority of the 91 studies administered the measure at any point in pregnancy (44.0%); 1.1% measured pregnancy trauma in the first trimester, 9.9% in the second trimester, 24.2% in the third trimester, 9.9% in the first or second trimester (ie, participants in either trimester), 8.8% in the second or third trimester, and 2.2% measured at multiple points in pregnancy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

When measures of PSPT were administered during pregnancy

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

More than half of the 91 studies measuring PSPT took place in North America (51.9%, n=42). Figure 4 shows the regional distribution of studies assessing PSPT during pregnancy.

Figure 4.

Regional distribution in the assessment of PSPT during pregnancy

Givrad. A systematic review on the assessment of pregnancy-specific psychological trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025.

In considering the broader systematic review of psychological trauma in pregnancy (N=576), we were next interested in understanding what portion of studies assessing psychological trauma in each region were focused on or had included an assessment of PSPT to ascertain whether the assessment of PSPT was more prominent in some regions than others. Across 91 studies assessing PSPT, 21.4% were in Asia, 0% were in Central America, 21.7% were in Europe, 15.8% were in the Middle East or Northern Europe, 16.8% were in North America, 3.7% were in Oceania, 8.7% were in South America, and 8.7% were in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Discussion

Principal findings

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the extent to which psychological trauma measured in pregnancy captured pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT). The findings confirmed the two main hypotheses our research team had developed based on our clinical experience. First, less than 20% of the studies reviewed examining psychological trauma in pregnancy included any measure of PSPT. This confirmed our hypothesis that even though PSPT is a prominent contributor to how women and their partners experience and understand their current and subsequent pregnancies and their relationships with their healthcare team and their child, PSPT is inadequately studied and assessed, with no existing PSPT screening measure in existence. Furthermore, close to 60% of the studies assessing PSPT used an in-house measure, with the remaining studies using broader questionnaires that include some individual items pertaining to PSPT. For example, the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire probes for miscarriage and abortion,56 the Life Events Scale for Pregnant Women asks about stillbirth, abortion, or miscarriage,59 and the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire assesses fear of childbirth.55 Although using previously validated questionnaires to examine psychological trauma has merit, such measures were not designed to more comprehensively assess PSPT and will inevitably miss some important types of PSPT. From a research perspective, not having commonly used and validated screeners for PSPT leads to methodological differences between studies that weaken the reliability and generalizability of the findings. From a clinical perspective, the absence of reliable and valid PSPT measures limits the translation of these methods to screening patients, and any PSPT assessment becomes clinician-dependent.

Clinically, women who have experienced prior PSPT are at higher risk of experiencing significant anxiety, depression, or symptoms of PTSD in subsequent pregnancies.31,32,41,45 In many cases, they struggle with establishing a trusting relationship with their obstetrics team and worry about losing their autonomy and control, not being heard, and being re-traumatized during their current or subsequent pregnancy.65,66 For many pregnant women who have experienced PSPT, interacting with the healthcare system, going to the clinics or hospital setting, or hearing alarms or sirens leads to fear of childbirth and can trigger PTSD symptomatology.67 For those who decide to undergo subsequent pregnancies, it is difficult to avoid trauma reminders or triggers entirely, resulting in some degree of reliving or re-experiencing the trauma.45,66,68 Research on perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) has taught us that relying solely on patient reports or clinician's ability to identify concerns with mood or anxiety is inadequate, and there is a need for systematic screening of PMADs during the perinatal period, supported by appropriate referral and treatment pathways.69, 70, 71 Similarly, without systematic and comprehensive screening, the healthcare team will not reliably become aware of patient history regarding PSPT. In turn, critically, individualized trauma-informed care cannot be delivered during the perinatal period if there is no awareness of the history of PSPT.

Trauma is in the eye of the beholder,49 and the same event can have different repercussions for different individuals based on their unique psychology, support system, history of trauma, and life experiences.67,72 For instance, first-trimester miscarriage or vaginal bleeding that does not end in a loss may not be perceived as traumatic by some, including the healthcare team, but might be experienced as traumatic by the pregnant woman/person. Furthermore, some individuals can develop PTSD symptomatology following PSPT, whereas others may demonstrate subthreshold symptoms. Our findings from this systematic review show only 12% of studies assessing PSPT also screened for PTSD. The presence of current PTSD associated with PSPT has significant treatment implications and can help inform maternal and infant outcome research findings in more nuanced ways.

It is important to note that most studies reviewed here assessing PSPT did not use a specific time point in pregnancy for their assessment, and very few studies examined PSPT during the first trimester of pregnancy. From a clinical standpoint, PSPT needs to be evaluated at least at two stages in the perinatal period: at the beginning of the pregnancy and after childbirth. Screening for PSPT at the beginning of the pregnancy, ideally at the first prenatal visit, allows for collaborative, trauma-informed care throughout the perinatal period. Trauma-informed care ensures the patient has the experience of being seen and heard, is an active participant in their care, and enhances their sense of control and autonomy. Assessment of PSPT after childbirth ensures capturing experiences related to the current pregnancy and providing support and intervention as needed to put the parent-infant dyad and family system on the right path. Additionally, timely implementation of trauma-responsive care leaves more time for preventative or therapeutic approaches to minimize medical and psychiatric complications during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period.

Perceptions of pregnancy and psychological trauma vary across the world and are shaped by cultural, clinical, and policy priorities. We found here that nearly half of the studies measuring PSPT were from North America. Although it seems that studies examining PSPT were more prominent in North America, we note that studies of PSPT consist of only 14% of studies evaluating any kind of psychological trauma during pregnancy in this region included in the broader systematic review.50 These regional findings in North America mirror the proportion of studies elsewhere in the world that assess PSPT in comparison to any other type of psychological trauma during pregnancy. Taken together, we do not detect a regional difference in prioritizing PSPT research among investigations of psychological trauma in pregnancy. PSPT is, therefore, understudied and underappreciated globally.

Our study shows that there is a critical need to systematically and comprehensively study the impact PSPT has on the individual and family's health and wellbeing, the health of subsequent pregnancies and next offspring, and the ways in which PSPT can shape and negatively impact the parent-child relationships with current and future children. Such a call to action necessitates the development of a comprehensive PSPT screening tool that can be researched, validated, and used in the clinical setting.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review was a secondary analysis of studies assessing PSPT from a broader systematic review we conducted to examine how psychological trauma during pregnancy has been assessed in the literature to date.50 The strengths included an interdisciplinary team of perinatal psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and researchers in designing and implementing the systematic review. This interdisciplinary team was also involved in the screening and data extraction steps leading to greater accuracy in the two-step verification and discussions for conflict resolution. However, this work has some limitations. First, a number of studies were not included in the broader systematic review as we could not access their full text (n=56), they were not written in English (n=19), or were conference abstracts or not peer-reviewed articles (n=196). Second, we categorized PSPT measures as being previously published (vs being in-house measures) if they were published or had been used in more than one study; however, being used in more than one study does not necessarily mean those measures are reliable and valid. Third, this systematic review provides descriptive data about how and when PSPT has been assessed during pregnancy. Inferential statistics related to different variables, treatment interventions, and outcome measures, such as prevalence estimates or effect sizes, were not included. Even so, the public availability of the studies identified and data extracted through this review would provide an important basis for future directions in research and clinical work on screening PSPT and understanding the multitude of effects of PSPT on the individual and family's health and delivery of care.

Conclusions and implications

Pregnancy-specific psychological trauma (PSPT) consists of a group of underrecognized and understudied psychologically traumatic experiences rooted in the individual's current and previous preconception and perinatal experiences (Table 1). PSPT can have long-lasting effects on the individual's physical and emotional well-being, in many cases, even if followed by subsequent successful and nontraumatic pregnancies and childbirths. PSPT can impact individuals' attitudes and experiences in subsequent perinatal periods and with their current and future children. Some forms of PSPT, such as traumatic birth, premature birth, and late fetal and early neonatal loss, have received more attention. Yet, there continues to be a scarcity of research-informed support services and interventions for individuals in the aftermath of such traumatic events and throughout their subsequent pregnancies and parenting. Other forms of PSPT, such as miscarriage, early fetal loss, medically complex pregnancies, and history of infertility or challenges encountered when undergoing fertility treatments, despite their high prevalence, are less recognized and need to be better studied and understood.

The findings of this systematic review necessitate a call to action to 1) create and validate a comprehensive screening measure to assess PSPT, taking into account the subjective nature of trauma; 2) better study all forms of PSPT and their impact on women/the pregnant person's physical and emotional well-being, challenges they face in subsequent pregnancies, and their parenting of current and future children; 3) following ACOG's recommendations, educate the obstetric, neonatology, and pediatric teams on trauma-informed approaches for patients who have experienced PSPT; and 4) instigate screening for current PTSD following a positive screening for PSPT.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Soudabeh Givrad: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kathryn M. Wall: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Lindsey Wallace Goldman: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Jin Young Shin: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Eloise H. Novak: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Amanda Lowell: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Francesca Penner: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Michèle J. Day: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Lea Papa: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Drew Wright: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Helena J.V. Rutherford: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [KW, T32NS041228, F31DA059248; FP, F32DA055389; HR, R01 DA050636, R01 HD108218] and Alkermes, Inc. [AL, Pathways Research Award].

References

- 1.Davis EP, Narayan AJ. Pregnancy as a period of risk, adaptation, and resilience for mothers and infants. Dev Psychopathol. 2020;32(5):1625–1639. doi: 10.1017/S0954579420001121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxbe D, Rossin-Slater M, Goldenberg D. The transition to parenthood as a critical window for adult health. American Psychologist. 2018;73(9):1190–1200. doi: 10.1037/amp0000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Kady D, Gilbert W, Xing G, Smith L. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of assaults during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):357–363. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000151109.46641.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MV, Gotman N, Yonkers KA. Early childhood adversity and pregnancy outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(4):790–798. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freaney PM, Harrington K, Molsberry R, et al. Temporal trends in adverse pregnancy outcomes in birthing individuals aged 15 to 44 years in the United States, 2007 to 2019. JAHA. 2022;11(11) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.025050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal A, Wenger NK. Hypertension during pregnancy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(9):64. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart AL, Payne JL. Perinatal depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46(3):447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2023.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakhtawar S, Sheikh S, Qureshi R, et al. Risk factors for postpartum sepsis: a nested case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):297. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02991-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heslet Koss MP. Somatic consequences of violence against women. Arch Fam Med. 1992;1(1):53–59. doi: 10.1001/archfami.1.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCrone PR, editor. Paying the Price: The Cost of Mental Health Care in England to 2026. King's Fund; 11–13 Cavendish Square London W1G 0AN: 2008. www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolezal T, McCollum D, Callahan M. The Academy on Violence & Abuse; 14850 Scenic Heights Road, Suite 135A Eden Prairie, MN 55344: 2009. Hidden Costs in Health Care: The Economic Impact of Violence and Abuse.www.avahealth.org [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prevent Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachdeva J, Nagle Yang S, Gopalan P, et al. Trauma informed care in the obstetric setting and role of the perinatal psychiatrist: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63(5):485–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamun A, Biswas T, Scott J, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, the risk of pregnancy complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenan-Devlin LS, Borders AEB, Freedman A, et al. Maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment and adverse birth outcomes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10380. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36831-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal S, Prasad R, Mantri S, et al. A comprehensive review of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and its adverse effects on maternal and fetal health. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39262. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah PS, Shah J. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Women's Health. 2010;19(11):2017–2031. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha S, Masho SW. Intimate partner violence and utilization of prenatal care in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(5):911–927. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wamser R, Ferro RA. Cumulative trauma, posttraumatic stress, and obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2024;16(8):1374–1381. doi: 10.1037/tra0001579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caring for patients who have experienced trauma: ACOG committee opinion. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(4):e94–e99. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004326. Number 825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

- 22.Purkey E, Patel R, Beckett T, Mathieu F. Primary care experiences of women with a history of childhood trauma and chronic disease: trauma-informed care approach. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(3):204–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miscarriage. March of Dimes. 2023. Accessed Aug. 20, 2024. https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/miscarriage-loss-grief/miscarriage

- 24.Hoyert DL, Gregory E. Cause-of-death data from the fetal death file. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2022;71(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newborn mortality. World Health Organization. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality#:∼:text=There%20are%20approximately%206500%20newborn,to%202.3%20million%20in%202022. Accessed August 20, 2024.

- 26.A profile of prematurity in United States. March of Dimes Report. Accessed August 28, 2024.https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/tools/prematurityprofile.aspx?reg=99#Preterm_Birth

- 27.Preterm birth. World Health Organization. Accessed August 28, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth

- 28.The toll of birth trauma on your health. March of Dimes. 2023.https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/postpartum/toll-birth-trauma-your-health#:∼:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Institutes,long%20after%20the%20birth%20itself. Accessed August 20, 2024.

- 29.Goutaudier N, Bertoli C, Séjourné N, Chabrol H. Childbirth as a forthcoming traumatic event: pretraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy and its psychological correlates. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2019;37(1):44–55. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2018.1504284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, et al. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1659-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackmore ER, Côté-Arsenault D, Tang W, et al. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(5):373–378. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Leary J. Subsequent pregnancy: healing to attach after perinatal loss. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(S1):A15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-15-S1-A15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson PA, Kavanaugh K. Supporting parents during and after a pregnancy subsequent to a perinatal loss. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1998;12(2):63–66. doi: 10.1097/00005237-199809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunfeld JAM, Taselaar-Kloos AKG, Agterberg G, Wladimiroff JW, Passchier J. Trait anxiety, negative emotions, and the mothers’ adaptation to an infant born subsequent to late pregnancy loss: a case–control study. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17(9):843–851. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199709)17:9<843::AID-PD147>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis DL, Stewart M, Harmon RJ. Postponing pregnancy after perinatal death: perspectives on doctor advice. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28(4):481–487. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitz K. Vulnerable child syndrome. Pediatr Rev. 2019;40(6):313–315. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Givrad S, Hartzell G, Scala M. Promoting infant mental health in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)_ a review of nurturing factors and interventions for NICU infant-parent relationships. Early Hum Dev. 154. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105281 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Greene MM, Rossman B, Patra K, Kratovil AL, Janes JE, Meier PP. Depression, anxiety, and perinatal-specific posttraumatic distress in mothers of very low birth weight infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(5):362–370. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busse M, Stromgren K, Thorngate L, Thomas KA. Parents’ responses to stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse. 2013;33(4):52–59. doi: 10.4037/ccn2013715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoge MK, Heyne E, Nicholson TDF, et al. Vulnerable child syndrome in the neonatal intensive care unit: a review and a new preventative intervention with feasibility and parental satisfaction data. Early Hum Dev. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro GD, Séguin JR, Muckle G, Monnier P, Fraser WD. Previous pregnancy outcomes and subsequent pregnancy anxiety in a Quebec prospective cohort. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(2):121–132. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2016.1271979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez AN, Ambia AM, Fomina YY, et al. A prospective study of antepartum anxiety screening in patients with and without a history of spontaneous preterm birth. AJOG Global Reports. 2023;3(4) doi: 10.1016/j.xagr.2023.100284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen B, Forgaard A, Nordsletta AHS, Røseth I. “I shut it out”: expectant mothers’ fear of childbirth after a traumatic birth—a phenomenological st. doi:10.1080/17482631.2022.2101209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Calpbinici P. The relationship between traumatic childbirth perception, desire to avoid pregnancy, and sexual quality of life in women. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Stramrood C, Slade P. In: Bio-Psycho-Social Obstetrics and Gynecology. Paarlberg KM, Van De Wiel HBM, editors. Springer International Publishing; Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland: 2017. A Woman Afraid of Becoming Pregnant Again: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following Childbirth; pp. 33–49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen MJ, Kair LR, Schwarz EB, Creinin MD, Chang JC. Future pregnancy considerations after premature birth of an infant requiring intensive care: a qualitative study. Women's Health Issues. 2022;32(5):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2022.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottvall K, Waldenström U. Does a traumatic birth experience have an impact on future reproduction? BJOG. 2002;109(3):254–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shorey S, Yang YY, Ang E. The impact of negative childbirth experience on future reproductive decisions: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(6):1236–1244. doi: 10.1111/jan.13534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck CT. Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nurs Res. 2004;53(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rutherford H, Wall KM, Goldman Wallace L, et al. Operationalizing psychological trauma in pregnancy: a systematic review. (Under Review).

- 51.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright D, Demetres M, Givrad S, Rutherford H. A systematic review of the measurement of psychological trauma during pregnancy. PROSPERO. 2022 https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022384173 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: www.covidence.org.

- 54.Wolfe J, Kimerling R, Brown PJ, Chrestman KR, & Levin K. (1996). Life Stressor Checklist--Revised (LSC-R) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. 10.1037/t04534-000. [DOI]

- 55.Wijma K, Wijma B, Zar M. Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19(2):84–97. doi: 10.3109/01674829809048501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: the traumatic life events questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):210–224. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.WHO Multi-country study on women's health and life experiences: questionnaire. GWH/WHO, 20 Ave Appia, CH 1211 Geneva 27: World Health Organization. 2005.

- 58.Brockington, I. F. (2006). The Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health. Ian Brockington, Eyry Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=GaWoIgAACAAJ.

- 59.Wei Qian, Zou Jiaojiao, Ma Xuemei, Xiao Xirong, Zhang Yunhui, Shi Huijing. Prospective associations between various prenatal exposures to maternal psychological stress and neurodevelopment in children within 24 months after birth. J Affect Disord. 2023;327:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Husain Nusrat, Parveen Asia, Husain Meher, Saeed Qamar, Jafri Farhat, Rahman Raza, Tomenson Barbara, Chaudhry Imran B. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of perinatal depression: a cohort study from Urban Pakistan. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(5):395–403. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Norbeck JS. Modification of life event questionnaires for use with female respondents. Res Nurs Health. 1984;7(1):61–71. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clarfield L, Little D, Svendrovski A, Yudin MH, De Souza LR. Single-centre retrospective cohort study of demographic characteristics and perinatal outcomes in pregnant refugee patients in Toronto, Canada. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2023;25(3):529–538. doi: 10.1007/s10903-022-01447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brockington Ian, Chandra Prabha, Bramante Alessandra, Dubow Hettie, Fakher Walaa, Garcia-Esteve LLuïsa, Hofberg Kristina, et al. The stafford interview: a comprehensive interview for mother-infant psychiatry. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(1):107–112. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0683-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown George William, Harris Tirril. Free Press; New York: 1978. Social Origins of Depression : A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. Social Origins of Depression : A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. 1st American ed. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenfield M, Jomeen J, Glover L. After last time, would you trust them?’ – rebuilding trust in midwives after a traumatic birth. Midwifery. 2022;113 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vignato J, Georges JM, Bush RA, Connelly CD. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the perinatal period: a concept analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23-24):3859–3868. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Størksen HT, Garthus-Niegel S, Vangen S, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of previous birth experiences on maternal fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(3):318–324. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fenech G, Thomson G. Tormented by ghosts from their past’: A meta-synthesis to explore the psychosocial implications of a traumatic birth on maternal well-being. Midwifery. 2014;30(2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum: ACOG clinical practice guideline no. 4. Obstetr Gynecol. 2023;141(6):1232–1261. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson A, Stevenson E, Moeller L, McMillian-Bohler J. Systematic screening for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders to promote onsite mental health consultations: a quality improvement report. J Midwife Womens Health. 2021;66(4):534–539. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goodman JH. Tyer-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health. 2010;19(3):477–490. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watson K, White C, Hall H, Hewitt A. Women's experiences of birth trauma: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2021;34(5):417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]