Abstract

BMD, an important marker of bone health, is regulated by a complex interaction of proteins. Plasma proteomic analyses can contribute to identification of proteins associated with changes in BMD. This may be especially informative in stages of bone accrual and peak BMD achievement (ie, adolescence and young adulthood), but existing research has focused on older adults. This analysis in the Study of Latino Adolescents at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes (SOLAR; n = 304; baseline age 8-13, 100% Hispanic) explored associations between baseline proteins (n = 653 proteins) measured with Olink plasma protein profiling and repeated annual DXA measures of BMD (average of 3.2 visits per participant). Covariate-adjusted linear mixed effect regression models were applied to estimate longitudinal protein—BMD associations using an adjusted p value cutoff (p < .00068). Identified proteins were imported into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database to determine significantly enriched protein pathways. Forty-four proteins, many of which are involved in inflammatory processes, were associated with longitudinal changes in total body BMD, including several proteins previously linked to bone health such as osteopontin (SPP1) and microfibrillar-associated protein 5 (MFAP5; both p < .00068). These 44 proteins were associated with enrichment of pathways including PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, supporting results from existing proteomics analyses in older adults. To evaluate whether protein associations were consistent into young adulthood, linear mixed effect models were repeated in a young adult cohort (n = 169; baseline age 17-22; 62.1% Hispanic) with 346 available overlapping Olink protein measures. While there were no significant overlapping longitudinal protein associations between the cohorts, these findings suggest differences in protein regulation at different ages and provide novel insight on longitudinal protein associations with BMD in overweight/obese adolescents and young adults of primarily Hispanic origin, which may inform the development of biomarkers for bone health in youth.

Keywords: DXA, cytokines, general population studies, osteoimmunology, biochemical markers of bone turnover

Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the development of BMD which can predict lifelong bone health.1 In humans, BMD peaks during young adulthood and slowly declines over the rest of the lifespan,1 with timing for these peaks ranging according to skeletal site and biological sex.2 Low peak BMD has been identified as a risk factor for the development of adulthood osteopenia and osteoporosis, diseases characterized by low bone mass that currently affect millions of adults in the United States, and are increasing in prevalence.3 Hispanic individuals in the United States demonstrate higher prevalence of osteoporosis than other ethnic groups3 and likely also suffer from lower rates of osteoporosis screening and treatment compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts.4 Yet research on bone health often fails to include this population.

Bone is comprised of metabolically active tissue that is involved in constant regeneration and repair while striving for homeostasis. Disruption of this balance can result in bone damage and disease.5 Recent evidence demonstrates the detrimental impact of chronic low-grade inflammation on bone health. Chronic inflammation, driven in part by inflammatory cytokines, which can disrupt normal bone metabolism and accelerate resorption, leading to lower BMD irrespective of aging.6 Further, inflammation can contribute to the pathogenesis of bone disease during the aging process, a process known as “inflammaging.”7 Emerging-omics technologies, including genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, have shown promising results in identifying biomarkers involved in bone development and disease pathogenesis.8 Specifically, proteomics approaches can allow for the quantification of hundreds of proteins simultaneously, thereby revealing biological functions and protein interaction networks related to human health and disease.9 Due to the important role that proteins play in bone metabolism, the application of proteomic methods has the potential to identify potential molecular markers associated with changes in BMD.

Human evidence applying quantitative proteomic methods to understand mechanisms behind low BMD is sparse.8 Existing studies have primarily comprised of small sample sizes of older adults and typically compare protein expression between individuals with high and low BMD in a case-control fashion.10–14 Many of these consist of racially homogenous populations frequently focused on Caucasian or Chinese individuals, and many studies have only included participants of one sex (with females being the primary focus).11–15 One longitudinal study investigated proteins associated with prospective changes in BMD but included only older non-Hispanic White men.15 Furthermore, existing proteomic evidence has mainly focused on investigating associations between proteins and BMD later in adulthood, when low BMD is already present. No previous studies have attempted to elucidate proteomic markers associated with BMD during stages of bone accrual or peak BMD achievement (ie, adolescence and young adulthood). Furthermore, the generalization of results from older populations to younger individuals may not be appropriate, and there is a lack of Hispanic representation in proteomic bone research studies, despite higher rates of osteoporosis in adults of this ethnic group. Application of quantitative proteomic methods can identify protein markers associated with longitudinal changes in BMD, especially in understudied young and ethnically diverse populations, and provide insights for targeted early osteoporosis prevention and treatment.

The present work aimed to identify proteomic markers and pathways associated with repeated measures of BMD in a cohort of Hispanic adolescents by utilizing gold-standard measures of bone density using DXA16 and Olink proteomic panels of inflammatory and cardiometabolic proteins (>600 proteins). Olink proteomic methods utilize a proximity extension assay technology and have been validated for technical robustness, demonstrating good reproducibility and stability across multiple studies.17,18 Additionally, the present study examined a subset of protein markers in relation to BMD in a second, independent cohort of primarily Hispanic young adults likely past the period of peak BMD accrual and in the period of peak BMD achievement. To our knowledge, this is the first and largest longitudinal study applying proteomic methods to evaluate associations between proteins and BMD in an adolescent population during a period of bone accrual.

Materials and methods

Study populations

The SOLAR cohort

The Study for Latino Adolescents at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes (SOLAR) included 328 Hispanic youth from urban Los Angeles, CA. Participants were recruited in 2 waves between 2001 and 2012.19,20 Recruitment primarily occurred through local metabolic clinics, as well as via local advertisements, health fairs, and word of mouth. Inclusion criteria consisted of age at baseline between 8 and 13 yr old; self-reported Hispanic or Latino ancestry of all 4 grandparents; an absence of type 1 diabetes (T1D) or type 2 diabetes (T2D); a family history T2D in at least one parent; and a BMI ≥the 85th percentile for sex and age based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) standards. Participants taking medications known to affect insulin or glucose metabolism were excluded. This study was approved by the University of Southern California (USC) IRB. Written informed assent and consent were provided by participants and their parents, respectively.

Participants underwent annual visits at the USC General Clinic Research Center or Clinical Trials Unit. Of 328 baseline participants, 304 had available measurements of proteomic markers and BMD and were included in the analysis (Figure S1). Data from all visits up until age 19 were included for these participants, resulting in 1127 unique visits (average of 3.2 visits per individual).

The Meta-AIR cohort

The Metabolic and Asthma Incidence Research (Meta-AIR) study took place between 2014 and 2018 and included a subset of 174 individuals that participated in the Southern California Children’s Health Study.21 Participants were aged 17-23 yr old at baseline and were included if they met the following criteria: a history of overweight or obesity in early adolescence; an absence of T1D or T2D; and absence of any other medical conditions. Those taking medications known to affect glucose metabolism were excluded. Participants were invited for a follow-up visit between 2020 and 2022. All study visits took place at the Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute at USC.

Of 174 participants at baseline, 169 had available measurements of both proteomic markers and BMD and provided consent for future use of biospecimens and were included in the analysis (Figure S1). Of these, 85 had complete data from a second visit that was 4.1 yr later, on average (SD = 1.1 yr). This study was approved by the USC IRB. Written informed assent/consent was obtained from participants or their guardians (if under age 18).

Proteomic measures

In both cohorts, plasma samples were collected during 2-hr oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) at the 2-hr timepoint and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. In SOLAR, the proximity extension assay was used to measure baseline levels of plasma proteins from 2 Olink Explore 384 panels: 369 proteins from the Cardiometabolic Panel I and 368 proteins from the Inflammation panel.22 Proteins were excluded if over 50% of observations had measures below the limit of detection (LOD). From the Cardiometabolic and Inflammation panels, 28 and 53 proteins were excluded, respectively. Of 656 remaining protein measures, 3 proteins overlapped between the 2 panels, the values of which were averaged, resulting in 653 unique baseline proteins available for analysis (Figure S2). In Meta-AIR, only the Olink Explore 384 Cardiometabolic Panel I was utilized to measure plasma proteins. Of 369 proteins, 23 were below the LOD, resulting in a total of 346 measured proteins measured at baseline (Figure S2).

Pooled plasma samples from sample controls were utilized to assess the potential for variation between runs and plates. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variance, respectively, were as follows: SOLAR Cardiometabolic Panel I, 10% and 16%; SOLAR Inflammation Panel, 12% and 20%; Meta-AIR Cardiometabolic Panel I, 14% and 15%. Protein data were expressed in Normalized Protein eXpression values, representing Olink’s quantification units (log2 scale).

BMD measurements

In both cohorts, trained technicians performed DXA scans at all visits. In SOLAR, the Hologic QDR 4500 W model was utilized for whole-body scans at each visit. In Meta-AIR, whole-body scans were performed on the Hologic QDR 4500W or Horizon W models. Total body BMD was selected as the primary outcome variable due to its availability in both cohorts.

Covariates

As described previously, participants (and/or their guardians, when necessary) reported demographic information via questionnaires.19,21 In both cohorts, age, sex, and parental education level (less than high school, high school graduate, more than high school, or missing) were collected. Additionally, Meta-AIR participants self-identified their ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, or other).

In both cohorts, participants completed physical examinations at each visit. As described previously, the homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using results from the OGTTs.20 BMI (kg/m2) was calculated from clinical measurements of height (reported in meters) and weight (reported in kilograms). In SOLAR adolescents, BMI z-score was calculated using the CDC age- and sex-specific growth charts.23 Additionally, in SOLAR adolescents, a physical examination was performed by a physician at each visit to establish participants’ Tanner stage.24 In brief, individuals can be categorized into 1 of 5 categories, ranging from Tanner 1 (prepuberty) to Tanner 5 (post-puberty).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics analysis

In both cohorts, descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline characteristics of participants. Distributions of total body BMD were calculated within each cohort. Spaghetti plots were generated to evaluate the changes in BMD in reference to age for each participant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.0.

Protein association study in SOLAR

A protein association study (PAS) of available proteins in SOLAR was conducted to examine associations between baseline proteins and changes in BMD. To account for repeated BMD measurements, linear mixed-effect models with individual-level random intercepts were utilized. This modeling allows for inclusion of data from all participants, irregularly spaced measurements or missing data, including participants with only one measure of BMD (ie, baseline visit only).25 Models were adjusted for baseline age, and an interaction term of each protein with follow-up time was utilized to evaluate longitudinal associations. Specifically, for  individuals and

individuals and  visits, the following model was employed for each protein:

visits, the following model was employed for each protein:

|

(1) |

where  is the random intercept for each participant and

is the random intercept for each participant and  are the residuals. The

are the residuals. The  parameter was interpreted as the association between the protein and BMD at the baseline visit, while

parameter was interpreted as the association between the protein and BMD at the baseline visit, while  , which quantifies the annual change in BMD associated with different levels of protein, was interpreted as the longitudinal association between the protein and BMD. Associations were either positive (ie, higher protein levels associated with higher BMD) or negative (ie, higher protein levels associated with lower BMD). Associations did not consider potential roles of proteins as positive or negative regulators in bone health.

, which quantifies the annual change in BMD associated with different levels of protein, was interpreted as the longitudinal association between the protein and BMD. Associations were either positive (ie, higher protein levels associated with higher BMD) or negative (ie, higher protein levels associated with lower BMD). Associations did not consider potential roles of proteins as positive or negative regulators in bone health.

Models were additionally adjusted for sex, parental education (as a proxy for socioeconomic status, which has been associated with BMD trajectories26), study wave, and Tanner stage. Tanner stage was treated as a time-varying covariate. Pubertal stage is typically highly positively correlated with age, but adjustment for only baseline age and follow-up time reduced concerns of high correlation between age and Tanner status (as opposed to repeated age measures). Models were performed in the total cohort as well as in males and females separately. Finally, to examine model assumptions and probe for potential outliers, model diagnostics were performed on a base model (ie, covariate-only model with no protein terms). Histograms, scatter plots, and Q-Q plots of model residuals were created, and predicted random effect values were plotted for each subject.

To control for multiple testing, the effective number of tests (Meff)27 was calculated using principal components analysis (PCA). PCA was performed on all proteins and the single outcome, and eigenvalues were calculated. Using the Kaiser–Guttman rule,28 we summed all eigenvalues greater than 1 for proteins and outcome to determine the effective number of tests Meff, and calculated the adjusted p value as 0.05/Meff. In the present analysis, Meff for SOLAR was 73. Thus, associations passed the significance test for multiple comparisons in SOLAR if p < .05/73 = 0.00068. Proteins significantly associated with total body BMD at either baseline (ie,  ) or longitudinally (ie,

) or longitudinally (ie,  ) at the adjusted p value cutoff were used to generate a heatmap displaying t-statistics derived from the PAS.

) at the adjusted p value cutoff were used to generate a heatmap displaying t-statistics derived from the PAS.

STRING protein-protein interaction network analysis in SOLAR

The list of proteins significantly associated with longitudinal BMD changes (ie, proteins with a y4 term with a p < .00068) were imported into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database29 to construct protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. Additionally, STRING performs gene ontology (GO)30 pathway and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway31 enrichment analyses. STRING scores evidence from several channels used to categorize evidence of associations, including text mining, experiment data, and annotated pathways/complexes, and evaluates the number of “edges” detected, which represent functional annotations. Each PPI is assigned a score to indicate confidence levels of the interaction (low, 0.15; medium, 0.40; high, 0.70; highest, 0.90). Significant pathways are assigned q-values, which are their associated p values adjusted for false discovery rate calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.32 The default cutoff for significance in STRING is a q-value <0.05. We constructed and visualized the PPI networks by selecting proteins with interaction scores of 0.7 (high confidence) or higher and annotated significantly enriched pathways.

Supplementary analyses: further adjustment and potential effect modification

To further probe the potential influence of obesity in the SOLAR cohort, which consisted of individuals with overweight/obesity that were at risk of T2D, the main PAS models were repeated with BMI z-score treated as a covariate. We additionally explored the potential for effect modification by obesity status and insulin resistance, as well as effect modification by sex to determine whether associations were homogenous between females and males. For significant longitudinal protein associations determined by the PAS, the models from eqn (1) were updated with additional interaction terms: for each potential effect modifier (for obesity status, BMI z-score; for insulin resistance, HOMA-IR; and biological sex) we included  as well as the appropriate lower-order interactions (see Table S1 for further details on the modeling approaches). Any protein that demonstrated an interaction term (

as well as the appropriate lower-order interactions (see Table S1 for further details on the modeling approaches). Any protein that demonstrated an interaction term ( ) that was significant at the adjusted p value was assumed to have a longitudinal association with BMD that was modified by the variable being evaluated. The STRING pathway analysis was repeated after excluding any protein associations that were potentially modified by any of the evaluated variables.

) that was significant at the adjusted p value was assumed to have a longitudinal association with BMD that was modified by the variable being evaluated. The STRING pathway analysis was repeated after excluding any protein associations that were potentially modified by any of the evaluated variables.

Replicated PAS in Meta-AIR

In Meta-AIR young adults, associations were estimated between proteins in the Cardiometabolic I panel and BMD. Linear mixed-effect models using the same structure described in eqn (1) were employed and adjusted for the following covariates: sex, parental education, and race/ethnicity, and DXA type. The calculated Meff for the Meta-AIR cohort was 67, therefore the adjusted significance threshold was calculated as p < .05/67 = .00075. A heatmap was generated displaying proteins significantly associated with total body BMD at either baseline (ie,  ) or longitudinally (ie,

) or longitudinally (ie,  ) at this threshold. A table was constructed to compare longitudinal effect estimates from proteins from the Cardiometabolic 1 panel that were significant in either SOLAR (n = 13) or Meta-AIR (n = 3). As in SOLAR, potential effect modification by BMI, HOMA-IR, and sex was analyzed in Meta-AIR using the same analysis structure as previously described (see Table S1). Finally, in order to compare associations specifically in Hispanic participants, we performed a secondary analysis of the PAS in Meta-AIR after excluding non-Hispanic participants.

) at this threshold. A table was constructed to compare longitudinal effect estimates from proteins from the Cardiometabolic 1 panel that were significant in either SOLAR (n = 13) or Meta-AIR (n = 3). As in SOLAR, potential effect modification by BMI, HOMA-IR, and sex was analyzed in Meta-AIR using the same analysis structure as previously described (see Table S1). Finally, in order to compare associations specifically in Hispanic participants, we performed a secondary analysis of the PAS in Meta-AIR after excluding non-Hispanic participants.

Results

Baseline characteristics of each cohort are provided in Table 1. The SOLAR cohort was 57.6% male and an average age of 11.3 yr old at baseline (SD = 1.7 yr). At baseline, the average total BMD was 0.927 g/cm2 (SD = 0.101 g/cm2), and all participants with follow-up visits demonstrated increases in BMD over time (Figure S3). The Meta-AIR cohort was 55.0% male and with an average age of 19.9 yr old at baseline (SD = 1.3 yr). The average total BMD was 1.184 g/cm2 at baseline (SD = 0.112 g/cm2), and BMD remained relatively constant between visits for those with 2 visits (Figure S3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included participants in the SOLAR and Meta-AIR cohorts.

| Characteristic |

SOLAR

n = 304 |

Meta-AIR

n = 169 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | ||

| Age, yr | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 19.9 ± 1.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 129 (42.4) | 76.0 (45.0) |

| Male | 175 (57.6) | 93.0 (55.0) |

| Parental education | ||

| <High school | 144 (47.4) | 34 (20.1) |

| High school grad | 88 (28.9) | 24 (14.2) |

| >High school | 41 (13.5) | 105 (62.1) |

| Missing | 31 (10.2) | 6 (3.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 304 (100.0) | 105 (62.1) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 55 (32.5) | |

| Other | 9 (5.3) | |

| Tanner stage | ||

| 1 (prepuberty) | 93 (30.6) | |

| 2 (early puberty) | 114 (37.5) | |

| 3 (puberty) | 39 (12.8) | - |

| 4 (late puberty) | 38 (12.5) | |

| 5 (postpuberty) | 20 (6.6) | |

| Study wave | ||

| First wave | 226 (74.3) | - |

| Second wave | 78 (25.7) | |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 28.3 ± 5.7 | 29.9 ± 5.0 |

| BMI z-score | 2.0 ± 2.2 | - |

| HOMA-IR | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 17.8 ± 57.5 |

| Missing | 8 (2.6) | 61 (35.5) |

| Total BMD, g/cm 2 | 0.927 ± 0.101 | 1.184 ± 0.112 |

Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model of insulin resistance; Meta-AIR, Metabolic and Asthma Incidence Research; SOLAR, Study of Latino Adolescents at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes.

Results from the covariate-adjusted linear mixed effect models identified 48 unique proteins associated with either baseline BMD (n = 6) or longitudinal changes in BMD (n = 44; Figure 1). Baseline associations between protein expression and BMD were more positive than negative (4 to 2 associations, respectively) while longitudinal associations were primarily negative (31 associations compared to 13 positive associations). Two proteins, microfibrillar-associated protein 5 (MFAP5) and Xg glycoprotein (XG), demonstrated significant positive associations at baseline but significant negative associations over follow-up. Sclerostin (SOST) was significantly and positive associated with baseline BMD, but the longitudinal positive association was nonsignificant. Alternatively, amyloid beta precursor like protein 1 (APLP1) and protein kinase C-binding protein (NELL2) demonstrated significant negative associations at baseline but non-significant negative associations longitudinally (Figure 1). The base model appeared to meet model assumptions: the histogram of conditional residuals was normally distributed around 0 the scatterplot of scaled vs conditional residuals appeared homoscedastic, and the Q-Q plot of residuals appeared normal (Figure S4). Results were similar after adjustment for BMI z-score (Table S2).

Figure 1.

Heatmap of proteins associated with baseline or longitudinal changes in BMD in 304 SOLAR adolescents after adjustment, clustered by longitudinal test statistic value. Linear mixed effect models adjusted for sex, Tanner stage, parental education, and study wave.

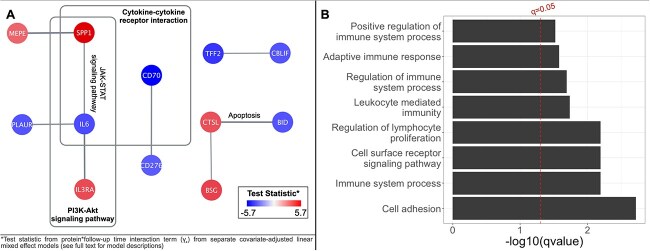

Proteins with longitudinal associations with BMD (n = 44) were imputed into STRING, yielding a clustered network with a local clustering coefficient of 0.517. The network contained 7 edges, which exceeded the expected number of edges (n = 1), indicating significantly more interaction between proteins than expected (PPI enrichment p = .0006). Functional enrichment results demonstrated 2 significant KEGG pathways: Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction (q value = 0.014) and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (q value = 0.022; Figure 2A). Additionally, functional enrichments were detected for 8 GO biological process pathways (all q value < 0.05; Figure 2B; Table S2). The most significant GO biological pathway associations were cell adhesion (q value = 0.002) and regulation of lymphocyte proliferation (q value = 0.006).

Figure 2.

Significant (q-value < 0.05) STRING PPI results for (A) KEGG pathways and (B) GO biological processes. Results identified from 44 proteins with significant (p < .00068) adjusted longitudinal associations in SOLAR adolescents (n = 304). *Test statistic from protein*follow-up time interaction term (Y4) from separate covariate-adjusted linear mixed effect models (see full text for model descriptions).

When evaluating potential effect modification in SOLAR by obesity and insulin resistance, no significant protein-BMD associations were found to be modified by HOMA-IR (results not shown). Two proteins demonstrated potential effect modification by BMI z-score: procathepsin L (CTSL) and intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM3; both interaction p < .0001). When analyses were stratified by those with BMI z-score above vs below the median at baseline (2.11), both proteins demonstrated stronger associations with BMD in those with higher BMI: in this group, ICAM3 was negatively associated with changes in BMD while CTSL was positively associated (Table S4). When evaluating effect modification by sex in SOLAR adolescents, a significant interaction was detected with scavenger receptor class F member 1 (SCARF1, p < .0001). After stratifying by sex, the association between SCARF1 and BMD was positive and stronger in males (Tables S5). When the STRING pathway analysis was repeated after excluding these 3 proteins, results were relatively unchanged; the 2 previously identified KEGG pathways remained significantly enriched along with 8 GO biological process pathways (Table S6).

In Meta-AIR, 3 proteins were significantly and negatively associated with longitudinal changes in BMD: endoglin (ENG), glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase (QPCT), and selectin E (SELE) (Figure 3). The associations between these proteins and BMD were not found to be modified by BMI, HOMA-IR, or sex (results not shown). Directionality of test statistics was compared for longitudinal protein associations from the Cardiometabolic I panel that were significant in either SOLAR (n = 13 proteins) or Meta-AIR (n = 3 proteins). In both cohorts, negative longitudinal associations were observed for XG, interleukin 19 (IL-19), chymotrypsin like elastase 3A (CELA3A), intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM3), spondin-2 (SPON2), complement C2 (C2), MFAP5, and SELE; consistent positive associations were not observed between cohorts (Table 2). When performing the analysis while only including Hispanic young adults, we found 3 significant associations: the negative longitudinal association with ENG remained significant, with negative significant associations also detected with ADGRE5 and ICAM3 (Figure S5). Thus, when analyzing Hispanic individuals specifically, ICAM3 demonstrated negative associations with BMD in both cohorts.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of proteins associated with longitudinal changes in BMD in 169 meta-AIR young adults after adjustment. Linear mixed effect models adjusted for sex, parental education, DXA type, and race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Comparison of adjusted test statistics for significant proteins from the Cardiometabolic I panel with significant longitudinal associations with BMD in SOLAR or Meta-AIR cohorts.

|

SOLAR

(n = 304) |

Meta-AIR

(n = 169) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Test statistic | p value | Significance a | Test statistic | p value | Significance a |

| XG | −6.120 | <.0001 | ** | −0.796 | .4285 | |

| SPP1 | 5.665 | <.0001 | ** | −0.960 | .3396 | |

| IL19 | −4.749 | <.0001 | ** | −0.830 | .4088 | |

| CELA3A | −4.278 | <.0001 | ** | −1.681 | .0964 | |

| SCARF1 | 4.125 | <.0001 | ** | −1.366 | .1756 | |

| CTSL | 3.995 | <.0001 | ** | −1.833 | .0703 | |

| ICAM3 | −3.995 | .0001 | ** | −3.249 | .0017 | * |

| SPON2 | −3.829 | .0001 | ** | −0.706 | .4822 | |

| SIGLEC7 | 3.816 | .0002 | ** | −2.275 | .0254 | * |

| C2 | −3.788 | .0002 | ** | −1.081 | .2829 | |

| CBLIF | −3.754 | .0002 | ** | 0.995 | .3226 | |

| PI3 | −3.578 | .0004 | ** | 0.239 | .8119 | |

| MFAP5 | −3.415 | .0007 | ** | −1.606 | .1120 | |

| QPCT | 3.323 | .0009 | * | −3.858 | .0002 | ** |

| ENG | 2.469 | .0137 | * | −3.615 | .0005 | ** |

| SELE | −1.170 | .2421 | −4.230 | <.0001 | ** | |

Significance.

* p < .05.

** p < .00068 in SOLAR or p < .00075 in Meta-AIR.

Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model of insulin resistance; Meta-AIR, Metabolic and Asthma Incidence Research; SOLAR, Study of Latino Adolescents at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes.

Discussion

Leveraging proteomic methods, this study identified several protein markers associated with longitudinal changes in total body BMD in 2 independent cohorts consisting of mainly overweight/obese participants: Hispanic adolescents and primarily Hispanic young adults. After adjustments for covariates and multiple testing, 44 proteins were significantly associated with changes in BMD in adolescents followed for an average of 3.2 yr; these proteins were found to be involved in several enriched pathways related to immune response and cellular metabolic processes, including the KEGG pathways cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Three proteins were negatively associated with changes in BMD in primarily Hispanic young adults, and patterns of longitudinal negative associations were similar between the cohorts for proteins such as ICAM3 and ENG. When non-Hispanic young adults were excluded, ICAM3 was significantly and negatively associated with BMD, consistent with the results in Hispanic adolescents. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study in young people evaluating associations between proteomic markers and changes in BMD; therefore, this analysis shed novel light on potential proteins and pathways associated with BMD in stages of bone accrual and peak BMD achievement, and evaluated whether these associations were modified by obesity, insulin resistance, and sex.

Several proteins associated with longitudinal changes in BMD in SOLAR adolescents have been shown to be associated with bone growth or metabolism in experimental evidence. For instance, osteopontin (SPP1), which was positively associated with changes in BMD, is a sialoprotein produced primarily by osteoblasts that play a role in biological processes including biomineralization and regulation of bone mass.33 Additionally, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein was positively associated with BMD changes, and has been shown to promote bone mineralization.34 The alpha1 chain of type IX collagen (COL9A1), which plays an important role in collagen formation and integrity,35 also demonstrated a strong positive association with BMD over follow-up. Alternatively, a negative longitudinal association was estimated with IL-6, a pro-inflammatory bone-resorption cytokine.36 This negative association has been further supported in human evidence; a longitudinal study on inflammatory cytokines in human adults found IL-6 to be a predictor of bone loss and resorption.37 Additionally, a genome-wide association study identified genetic variants at the gene that encodes the multiple EGF like domains 10 (MEGF10) protein to be associated with changes in BMD or bone mineral content in Hispanic children.38 In our analysis of Hispanic adolescents, MEGF10 demonstrated a significant positive association with BMD over the follow-up period. Further, MFAP5 has been identified as a regulator of osteogenesis and may serve as a therapeutic target in the treatment of osteoporosis.39 This protein demonstrated a complex association with BMD in our adolescent cohort: associations between MFAP5 and BMD were positive at baseline but negative over follow-up. The disparities between the baseline and longitudinal associations for each of these proteins demonstrate the importance of assessing longitudinal protein-BMD associations in order to capture associations that may be missed if evaluated at a single timepoint. The meaning of the directions of negative and positive relationships in terms of health outcomes later in life is yet to be known. By design, our study could not provide causal evidence on how these proteins are involved with bone modeling or remodeling processes, or how they positively or negatively regulate the communication between osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes within and outside bone remodeling units in humans. However, these results add valuable information about the exposures that are interacting with bone health.

Several proteins demonstrated significant associations with BMD at baseline, though longitudinal associations were non-significant; these included sclerostin (SOST) and metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1), with both proteins demonstrating positive baseline associations. SOST has been linked with bone density, loss, and fracture in studies on older populations,40 though this protein is commonly regarded as a negative regulator of bone formation.41 Additionally, a longitudinal proteomics study on proteins related to hip BMD and fracture in older non-Hispanic White men by Nielson et al. found TIMP1 to be associated with accelerated bone loss.15 This protein is involved in postnatal bone development42 but also degradation of the bone matrix,43 implying that TIMP1 may have positive associations with BMD earlier in life but negative impacts in later life. The positive associations with both SOST and TIMP1 in our adolescent cohort, in contrast to negative associations in older adults, highlight the importance of performing proteomic analyses in younger populations as opposed to generalizing results from studies with older samples.

Pathway analysis of GO biological processes revealed the role of BMD-related proteins in several immune functions, including regulation of immune system processes and adaptive immune response. These results echo associations found in other proteomic studies on older populations that utilized STRING PPI analyses: Nielson et al.’s15 longitudinal proteomics analysis determined that proteins related to BMD loss were enriched in immune system pathways, partially driven by immunoglobulin-related proteins. Additionally, a Mendelian randomization study by Han et al. evaluating causal associations of plasma proteins with BMD and osteoarthritis in Icelandic adults identified enrichment in several immune system processes identified in the current study, including positive regulation of immune system process.44 This study additionally shared KEGG pathway results with the present study, including significant enrichment of cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction. The skeletal and immune systems share several regulatory molecules, including cytokines, and the overlap between these 2 biological systems has been explored in the past in the interdisciplinary field known as “osteoimmunology.”45 Cytokines may be the link between the bone and immune systems, as they have been shown to mediate differentiation and activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts.46 A review of pathway and network analyses of genes related to osteoporosis by Guo et al. identified the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway and several other cytokine-related pathways to be associated with osteoporosis across multiple studies.47 In our adolescent cohort, negative associations were detected between changes in BMD and cytokines including IL-6 and cluster of differentiation 70 (CD70). The present results provide novel insight into associations between proteins related to BMD and immune system processes in adolescence and young adulthood.

The negative impact of inflammation on bone has been widely observed, especially in older age.7 The chronic inflammation associated with obesity-related metabolic status may interfere with bone health by causing bone loss.48 The present KEGG pathway results in adolescents discovered enrichment of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, a pathway involved in inflammation,49 from BMD-related proteins. Additionally, Han et al.’s44 Mendelian randomization study found significant enrichment of this pathway in relation to BMD- and osteoarthritis-related proteins in older adults, and Guo et al.’s47 pathway review identified this pathway as a network related to osteoporosis. Therefore, our results build on existing evidence associating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway to bone health.

Several associations between proteins and BMD were potentially modified by either obesity or sex. In regard to obesity, both proteins that demonstrated significant interactions with BMI z-score were found to have stronger associations with BMD in the higher BMI group after stratification. In sex-stratified analyses, SCARF1 demonstrated a stronger association with BMD in males. No previous studies have explored obesity and insulin resistance as effect modifiers in the associations between proteins and BMD in these age groups. Additionally, because many existing studies have been limited to one sex,11–15 much of the previous work has been unable to evaluate effect modification by sex. Thus, this study identifies the need for further examining the potential role of sex and metabolic disease in the associations between proteins and bone health.

Three proteins demonstrated significant negative associations with changes in BMD in young adults, including QPCT. Single nucleotide polymorphism studies have determined associations between variations in QPCT and BMD.50 We found no overlap between significant proteins between the overall SOLAR and Meta-AIR cohorts, once again reiterating the need to perform proteomic analyses at different life periods, because associations at one time point may not be generalizable to those in different periods of growth. Although the age gap between adolescence and young adulthood is quite small, these life periods are quite different in terms of BMD growth and maintenance: the former is associated with rapid BMD accrual, while the latter is when peak BMD is achieved.1 As demonstrated by the spaghetti plots of BMD changes in our cohorts, the participants in the adolescent cohort were primarily gaining BMD, while BMD in the young adult cohort was more stable over time. Thus, the mechanisms involved in the associations between biological proteins and changes in BMD may be different between these 2 periods. However, when we compared directionality of protein associations that were longitudinally significant in either cohort, we found similar (though nonstatistically significant) negative associations for several proteins. Further, when we subset to only Hispanic young adults, ICAM3 demonstrated a significant negative association with BMD, as was also determined in the adolescent cohort. Further research on these markers is necessary to evaluate their potential as negative biomarkers of BMD in different periods across the lifespan.

This is the first known study examining associations between proteomic profiles and longitudinal changes in BMD in adolescence and young adulthood, providing molecular insight on BMD development in the first 3 decades of life. The individuals included in the present analysis included populations that were previously understudied, both in terms of age and ethnic composition, as the existing studies primarily focus on small groups of racially homogenous older adults. Additionally, our study estimated longitudinal associations between proteins and BMD, while most of the current evidence is cross-sectional. Because baseline and longitudinal associations were quite different for many proteins, the present results further emphasize the need for longitudinal studies examining proteins associated with bone health, as estimation of associations at one timepoint may fail to capture important relationships. Further, no known studies have evaluated potential effect modification by sex, obesity, or insulin resistance. Our study applied stringent statistical adjustments, both by adjusting for relevant confounders to reduce potential confounding bias, and by setting strict cutoffs for statistical significance to control for the magnitude of performed tests and reduce the risk of false positives. Finally, we utilized Olink’s high-throughput proximity extension assay technology, which has demonstrated reproducibility and stability across studies.17,18

While our study fills gaps in the literature evaluating associations between proteomics and bone measures, several limitations persist. The targeted proteomic approach limited biomarker discovery to proteins measured in the included panels, which did not specifically include bone- or growth-related proteins; therefore the present results are primarily related to cardiometabolic health and inflammatory processes. Individual protein-BMD associations evaluated in our study were difficult to compare to existing proteomic bone research due to differences in measured proteins. Despite this, we detected similar enriched pathways to other studies that utilized the STRING database.15,44 Additionally, due to the historical nature of the SOLAR cohort, we did not have access to potentially relevant data such as total body less head BMD measures and descriptive socioeconomic information. A further limitation lies in the fact that result replication in our young adult cohort may have been limited due to small sample size at baseline (n = 169) and loss to follow-up prior to the second visit due to the COVID-19 pandemic interrupting enrollment of follow-up visits. Subsequent studies with larger sample sizes may detect more consistent results with those found in the adolescent cohort than were detectable with our decreased sample size.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply longitudinal proteomic methods to evaluate associations between proteins and changes in BMD in adolescents and young adults. After adjustment for confounders and application of stringent p value cutoffs, we detected numerous proteins and corresponding pathways associated with changes in total body BMD in adolescents. Proteins and pathways involved in inflammation were identified as having negative associations with BMD over the course of follow-up in an overweight/obese Hispanic population, which may affect potential to reach peak BMD and have long-term impacts on osteoporosis risk later in life. The validation of these protein markers as biomarkers of low BMD can be verified in future studies with larger sample sizes and additional age groups to reveal their potential role in the pathology of bone diseases such as osteoporosis.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Emily Beglarian, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Jiawen Carmen Chen, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Zhenjiang Li, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Elizabeth Costello, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Hongxu Wang, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Hailey Hampson, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Tanya L Alderete, Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD 21205, United States.

Zhanghua Chen, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Damaskini Valvi, Department of Environmental Medicine and Climate Science, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States.

Sarah Rock, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Wu Chen, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Nahid Rianon, Department of Internal Medicine, UTHealth McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Max T Aung, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Frank D Gilliland, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Michael I Goran, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, The Saban Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA 90027, United States.

Rob McConnell, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Sandrah P Eckel, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Miryoung Lee, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Brownsville, TX 77030, United States.

David V Conti, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Jesse A Goodrich, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Lida Chatzi, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90032, United States.

Author contributions

Emily Beglarian (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft). Jiawen Carmen Chen (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft), Zhenjiang Li (Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft), Elizabeth Costello (Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Hongxu Wang (Data curation, Software), Hailey Hampson (Formal analysis, Methodology, Software), Tanya Alderete (Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology), Zhanghua Chen (Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology), Damaskini Valvi (Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Sarah Rock (Investigation, Methodology, Project administration), Wu Chen (Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Nahid Rianon (Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Max T. Aung (Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Frank D. Gilliland Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology), Michael I. Goran (Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology), Rob McConnell (Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Sandrah P. Eckel (Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review & editing), Miryoung Lee (Methodology, Writing—review & editing), David V. Conti (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology), Jesse A. Goodrich (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft), Lida Chatzi (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft).

Funding

This work is primarily supported by grant R01ES029944 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). Funding for the SOLAR study came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01DK59211 (PI MG). Funding for the Meta-AIR study came from the Southern California Children’s Environmental Health Center grants funded by NIEHS (5P01ES022845, P30ES007048, 5P01ES011627), the United States Environmental Protection Agency (RD83544101), and the Hastings Foundation. Additional funding from NIH supported LC (R01ES030691, R01ES030364, R21ES029681, R21ES028903, and P30ES007048), N.R. and M.L. (R01AG078452), M.T.A. and E.C. (U01HG013288), R.M. (P2CES033433), and J.G. (K01ES036193). E.B. was supported by funding from the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation Los Angeles Founder Chapter.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individuals that participated in these studies. The data may be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Gordon CM, Zemel BS, Wren TAL, et al. The determinants of peak bone mass. J Pediatr. 2017;180:261–269. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berger C, Goltzman D, Langsetmo L, et al. Peak bone mass from longitudinal data: implications for the prevalence, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(9):1948–1957. 10.1002/jbmr.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526. 10.1002/jbmr.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Onizuka N, Onizuka T. Disparities in osteoporosis prevention and care: understanding gender, racial, and ethnic dynamics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2024;25:365-372. 10.1007/s12178-024-09909-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wawrzyniak A, Balawender K. Structural and metabolic changes in bone. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(15):1946. 10.3390/ani12151946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epsley S, Tadros S, Farid A, Kargilis D, Mehta S, Rajapakse CS. The effect of inflammation on bone. Front Physiol. 2021;11:511799. 10.3389/fphys.2020.511799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bi J, Zhang C, Lu C, et al. Age-related bone diseases: role of inflammaging. J Autoimmun. 2024;143:103169. 10.1016/j.jaut.2024.103169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang TL, Shen H, Liu A, et al. A road map for understanding molecular and genetic determinants of osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(2):91–103. 10.1038/s41574-019-0282-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo H, Wang L, Deng Y, Ye J. Novel perspectives of environmental proteomics. Sci Total Environ. 2021;788:147588. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. al-Ansari MM, Aleidi SM, Masood A, et al. Proteomics profiling of osteoporosis and osteopenia patients and associated network analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):10200. 10.3390/ijms231710200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang L, Liu YZ, Zeng Y, et al. Network-based proteomic analysis for postmenopausal osteoporosis in Caucasian females. Proteomics. 2016;16(1):12–28. 10.1002/pmic.201500005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zeng Y, Zhang L, Zhu W, et al. Quantitative proteomics and integrative network analysis identified novel genes and pathways related to osteoporosis. J Proteome. 2016;142:45–52. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.04.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu W, Shen H, Zhang JG, et al. Cytosolic proteome profiling of monocytes for male osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(3):1035–1046. 10.1007/s00198-016-3825-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang D, Wang Y, Lv J, et al. Proteomic profiling analysis of postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteopenia identifies potential proteins associated with low bone mineral density. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9009. 10.7717/peerj.9009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nielson CM, Wiedrick J, Shen J, et al. Identification of hip BMD loss and fracture risk markers through population-based serum proteomics. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(7):1559–1567. 10.1002/jbmr.3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roux C, Briot K. Current role for bone absorptiometry. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(1):35–37. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carlyle BC, Kitchen RR, Mattingly Z, et al. Technical performance evaluation of Olink proximity extension assay for blood-based biomarker discovery in longitudinal studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2022;13:889647. 10.3389/fneur.2022.889647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haslam DE, Li J, Dillon ST, et al. Stability and reproducibility of proteomic profiles in epidemiological studies: comparing the Olink and SOMAscan platforms. Proteomics. 2022;22(13-14):e2100170. 10.1002/pmic.202100170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goran MI, Bergman RN, Avila Q, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance and reduced β-cell function in overweight Latino children with a positive family history for type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;89(1):207–212. 10.1210/jc.2003-031402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodrich JA, Alderete TL, Baumert BO, et al. Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl substances and glucose homeostasis in youth. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129(9):097002. 10.1289/EHP9200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim JS, Chen Z, Alderete TL, et al. Associations of AIR pollution, obesity and cardiometabolic health in young adults: the meta-AIR study. Environ Int. 2019;133(PtA):105180. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olink Explore 3072 . Olink. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://olink.com/products-services/explore/

- 23. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2000;2002(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51(3):170–179. 10.1136/adc.51.3.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diggle P, Liang KY, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford Science; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crandall CJ, Merkin SS, Seeman TE, Greendale GA, Binkley N, Karlamangla AS. Socioeconomic status over the life-course and adult bone mineral density: the midlife in the U.S. study. Bone. 2012;51(1):107–113. 10.1016/j.bone.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wen SH, Lu ZS. Factors affecting the effective number of tests in genetic association studies: a comparative study of three PCA-based methods. J Hum Genet. 2011;56(6):428–435. 10.1038/jhg.2011.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goretzko D, Bühner M. Factor retention using machine learning with ordinal data. Appl Psychol Meas. 2022;46(5):406–421. 10.1177/01466216221089345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.STRING: functional protein association networks. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://string-db.org/

- 30. Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–D205. 10.1093/nar/gkt1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farrokhi V, Chabot JR, Neubert H, Yang Z. Assessing the feasibility of neutralizing Osteopontin with various therapeutic antibody modalities. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7781. 10.1038/s41598-018-26187-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zelenchuk LV, Hedge AM, Rowe PSN. Age dependent regulation of bone-mass and renal function by the MEPE ASARM-motif. Bone. 2015;79:131–142. 10.1016/j.bone.2015.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diab M, Wu JJ, Eyre DR. Collagen type IX from human cartilage: a structural profile of intermolecular cross-linking sites. Biochem J. 1996;314(Pt 1):327–332. 10.1042/bj3140327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lorenzo JA. The role of Interleukin-6 in bone. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(10):bvaa112. 10.1210/jendso/bvaa112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ding C, Parameswaran V, Udayan R, Burgess J, Jones G. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers predict change in bone mineral density and resorption in older adults: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1952–1958. 10.1210/jc.2007-2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hou R, Cole SA, Graff M, et al. Genetic variants affecting bone mineral density and bone mineral content at multiple skeletal sites in Hispanic children. Bone. 2020;132:115175. 10.1016/j.bone.2019.115175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li H, Zhou W, Sun S, et al. Microfibrillar-associated protein 5 regulates osteogenic differentiation by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin and AMPK signaling pathways. Mol Med. 2021;27(1):153. 10.1186/s10020-021-00413-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rianon NJ, Smith SM, Lee M, et al. Glycemic control and bone turnover in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Osteoporos. 2018;2018:7153021. 10.1155/2018/7153021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delgado-Calle J, Sato AY, Bellido T. Role and mechanism of action of sclerostin in bone. Bone. 2017;96:29–37. 10.1016/j.bone.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rifas L, Fausto A, Scott MJ, Avioli LV, Welgus HG. Expression of metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in human osteoblast-like cells: differentiation is associated with repression of metalloproteinase biosynthesis. Endocrinology. 1994;134(1):213–221. 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hatori K, Sasano Y, Takahashi I, Kamakura S, Kagayama M, Sasaki K. Osteoblasts and osteocytes express MMP2 and -8 and TIMP1, -2, and -3 along with extracellular matrix molecules during appositional bone formation. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;277(2):262–271. 10.1002/ar.a.20007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han BX, Yan SS, Yu Han, et al. Causal effects of plasma proteome on osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2023;112(3):350–358. 10.1007/s00223-022-01049-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takayanagi H. Mechanistic insight into osteoclast differentiation in osteoimmunology. J Mol Med (Berl). 2005;83(3):170–179. 10.1007/s00109-004-0612-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cai L, Lv Y, Yan Q, Guo W. Cytokines: the links between bone and the immune system. Injury. 2024;55(2):111203. 10.1016/j.injury.2023.111203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guo L, Han J, Guo H, Lv D, Wang Y. Pathway and network analysis of genes related to osteoporosis. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20(2):985–994. 10.3892/mmr.2019.10353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Forte YS, Renovato-Martins M, Barja-Fidalgo C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms associating obesity to bone loss. Cells. 2023;12(4):521. 10.3390/cells12040521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. He X, Li Y, Deng B, et al. The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in inflammation, cell death and glial scar formation after traumatic spinal cord injury: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Prolif. 2022;55(9):e13275. 10.1111/cpr.13275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huang QY, Kung AWC. The association of common polymorphisms in the QPCT gene with bone mineral density in the Chinese population. J Hum Genet. 2007;52(9):757–762. 10.1007/s10038-007-0178-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this article cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individuals that participated in these studies. The data may be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.