Abstract

Background

This electronic survey-based study aimed to explore the variations in treatment decisions made by dentists from different specialties in Saudi Arabia when treating anterior and posterior permanent teeth afflicted by molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) of varying severity.

Methods

A cohort of dental professionals, including general dentists, pediatric dentists, and restorative dentists/prosthodontists, participated in a validated electronic survey-based study between January and March 2023. The survey consisted of the following three sections: The first section collected demographic information from the participating dentists. The second part includes case scenarios and photographs of four clinical cases (two permanent first molars and two permanent incisors) diagnosed with MIH of varying degrees of severity. Following each case, the participants were asked to choose the treatment approach and final restorative material they preferred to manage the tooth in question. In the third part, participants were asked to select factors that influenced their treatment decisions.

Results

In total, 109 dentists responded to the questionnaire. For posterior permanent molars with both mild and severe MIH, general dentists and restorative dentists/prosthodontics preferred resin-based composite restoration. In contrast, pediatric dentists considered stainless steel crowns (SSCs) as the preferred modality. Resin infiltration was the most common treatment chosen for permanent anterior teeth with mild MIH. Resin-based composite restorations were predominantly chosen for severe cases. Tooth prognosis and dentist experience were among the top cited factors influencing the decision of preferred treatment in cases of permanent first molars diagnosed with MIH, and aesthetics was the most considered factor in cases of permanent incisors diagnosed with MIH.

Conclusion

According to the survey, different dental specialties manage MIH cases differently depending on the severity and type of permanent tooth (anterior/posterior).

Keywords: Knowledge, Children, Developmental enamel defect, MIH, Molar-incisors hypomineralization, Management, Restorative options

Background

Molar-incisor hypomineralization (MIH) is a multifactorial mineralization disorder of the enamel of systemic origin that affects one or more of the first permanent molars, with or without the involvement of the permanent incisors [1, 2]. The estimated global prevalence of MIH is 9.4%, with notable regional differences, showing the highest rate in the Americas at 17.7% and the lowest in Africa at 4.9% [3]. In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of MIH varies by region. It has been reported to be 8.6% in Jeddah City, 25.1% in the Al-Qassim region, and 40.7% in the capital city of Riyadh [4–7].

MIH-affected teeth can vary in clinical presentation and may present with several clinical challenges, particularly hypersensitivity, difficulties in obtaining profound anesthesia, behavioral challenges due to dental fear, extensive enamel loss, and problems performing proper restoration due to poor bond strength between the remaining MIH-affected enamel and resin-based restorations [8–11]. Therefore, they require more advanced treatment modalities than normally developed teeth [12, 13].

Based on this evidence, MIH is not diagnosed by general dentists as confidently as pediatric dentists, who are more familiar with this anomaly [2]. Multiple treatment options are available to manage MIH affected teeth ranging from early diagnosis and prevention to noninvasive aesthetic intervention and restorative options.

Owing to the high prevalence of MIH worldwide, it is necessary to study dentists’ confidence in managing MIH-affected teeth. A questionnaire study published in 2017 targeted Norwegian dentists and showed a wide variety of clinical strategies for the treatment of MIH-affected teeth [14]. Another survey-based study determined the knowledge, perceptions, and clinical management strategies for MIH among pediatric dentists in the United States. Most participants were familiar with MIH and confident when diagnosing teeth with MIH [15].

In 2016, a questionnaire administered to Saudi general and specialist dentists reported that most general dentists and specialists felt the need for further training in the management of MIH [16]. On the other hand, the treatment options used by dentists in Saudi Arabia and the factors influencing their decision to manage MIH-affected teeth may vary by dentist’s specialty and clinical experience. Therefore, this electronic survey-based study aimed to explore variations in treatment decisions made by dentists from different specialties in Saudi Arabia when treating permanent anterior and posterior teeth afflicted by MIH of varying degrees.

Methods

Ethical approval for this cross-sectional electronic survey was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Dentistry (approval number: 173-12-20). This study included dentists in Saudi Arabia between January and March 2023. This questionnaire was inspired by Wuollet et al. (2020) [17]. The survey was designed using Google Forms and sent electronically. The questionnaire was pretested by three dental academic professors who assessed and provided feedback on its clarity, ambiguity, and comprehension. The questionnaire was modified based on the professor’s feedback. The questionnaire was distributed to a convenient sample of dentists via a WhatsApp messaging application and Emails. The study considered the responses from general dentists, pediatric dentists, and restorative dentists/prosthodontists whom consented to participate in the survey study. The remaining responses were discarded. Reminders were sent two and four weeks after the initial dissemination. The survey took approximately 10–15 min to complete.

The electronic questionnaire comprised three sections. The first section gathered demographic information from the participating dentists, as well as questions about their workplace. The questionnaire did not include any identifiable information. The second part included four clinical cases (two permanent first molars and two permanent incisors) diagnosed with MIH with varying degrees of severity. Two certified pediatric dentists selected the images to be utilized in the questionnaire after reviewing the criteria issued by European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry [7, 10]. Each case was presented with a brief scenario and clinical photographs. The first case involved a 10-year-old patient with a fully erupted left maxillary first permanent molar (tooth #26), diagnosed with MIH, presenting with yellow-to-brown areas of opacity with minor Post-Eruptive Breakdown (PEB). The second case involved a 12-year-old patient with a fully erupted left maxillary permanent first molar (tooth #26) diagnosed with MIH, which displayed hypersensitivity and white-to-yellow opacities affecting the occlusal surface and buccal surface of the mesio-buccal cusp with moderate to severe PEB. The third case involved a 9-year-old patient with a fully erupted, hypomineralized maxillary permanent incisors, the focus was on the right maxillary permanent central incisor (tooth #11) with yellow demarcated opacity covering about two-thirds of the facial surface, and no PEB. The fourth case involved a 11-year-old patient who had a fully erupted, hypomineralized maxillary permanent incisors, and the focus was on the left maxillary central incisor (tooth #21) with white-to-yellow demarcated opacities covering at least two-thirds of the tooth surface and moderate to severe PEB.

Following each case, the participants were asked to choose the treatment approach they would use and the final restorative material they preferred to manage the tooth in question. Treatment options for MIH in permanent molars include fluoride varnish (FV), fissure sealant (FS), direct resin-based composite restoration, conventional glass ionomer (GI), resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI), zinc oxide eugenol (ZOE), interim restorative material (IRM), SSCs, indirect restorations (including inlays, onlays, porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, zirconia crowns, or E-Max crowns), extraction, and/or referral. For cases of MIH in the permanent incisors, the available treatments included bleaching, microabrasion, etch-bleach-seal, resin infiltration, partial veneers, and all treatments proposed for the posterior teeth, excluding SSCs. The participating dentists could select more than one material for their preferred management. In the third part, the participants were asked to select the factors influencing their treatment decisions. The factors considered were aesthetics, patient cooperation, experience, time and material availability, tooth prognosis, and number of affected teeth. Data from the electronic questionnaire were analyzed and summarized using frequencies and percentages. According to the research conducted by Alqahtani et al., it was estimated that there are 19,000 general dentists, 1,000 restorative dentists/prosthodontists, and 800 pedodontists in Saudi Arabia. Utilizing the OpenEpi Version 3 sample size calculator and presuming outcome frequencies ranging between 25% and 75%, it was determined that a minimum of 28 participants per group is necessary to achieve outcome estimation with 80% ± 10% confidence [18].

Results

In total, 109 dentists responded to the questionnaire, out of which 41 participants were general dentists (38.8%), 40 were pediatric dentists (33.9%), and 28 were restorative dentists/prosthodontists (27.2%). The distributions of age, sex, and workplace of the participating dentists are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and dental experience of the participants (N = 109)

| Variables | Total N = 109 |

General Dentist n = 41 |

Pediatric dentists n = 40 |

Restorative dentists/ prosthodontists n = 28 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤ 35 years | 74 (49.9) | 39 (95.1) | 18 (45.0) | 17 (60.7) |

| > 35 years | 35 (32.1) | 2 (4.9) | 22 (55.0) | 11 (39.3) | |

| Sex | Male | 37 (33.9) | 11 (26.8) | 12 (30.0) | 14 (50.0) |

| Female | 72 (66.1) | 30 (73.2) | 28 (70.0) | 14 (50.0) | |

| Workplace | Academia | 68 (62.4) | 20 (48.8) | 27 (67.5) | 21 (75.0) |

| Government | 29 (26.6) | 14 (34.1) | 10 (25.0) | 5 (17.9) | |

| Private | 12 (11.0) | 7 (17.1) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (7.1) | |

Figure 1. shows the treatment choices of the participating dentists based on their specialty for first and second cases of permanent first molars diagnosed with MIH of different severities. Resin-based composite restoration was the most preferred management approach by general dentists and restorative dentists/prosthodontics, in both mild and severe cases. In contrast, pediatric dentists chose SSCs as the preferred treatment in both cases. Restorative/prosthodontists did not consider SSCs in either case. Resin-based composite restoration was one of the most common treatment choices in the three groups. When contrasting the chosen management options for mild and severe molar cases, the favoured restorative management was not remarkably influenced by case severity, as evidenced by the consistent ranking of options across all three groups for both mild and severe cases.

Fig. 1.

Responses of the participating dentist to the first and second cases of MIH. MIH: Molar incisor hypomineralization; FV: Fluoride varnish; FS: Fissure sealant; RBC: Resin-based composite restoration; GI: Conventional glass ionomer; RMGI: Resin-modified glass ionomer; SSC: Stainless steel crown; Indirect: Indirect restorations including inlays, onlays, porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, zirconia crowns, or E-Max crowns; No ttt: no treatment, Referral: referral to other specialties

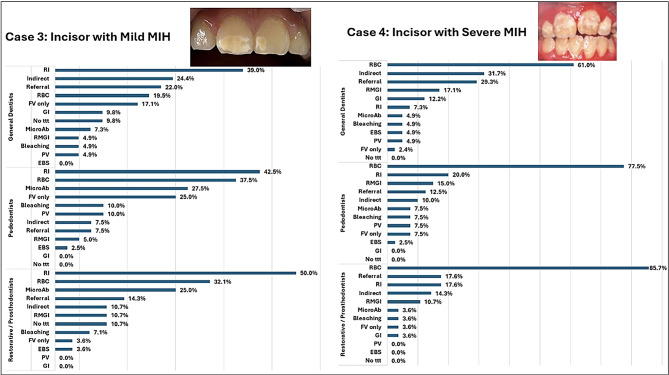

Figure 2 shows the treatment choices of the participating dentists, based on their specialty, for the third and fourth cases of permanent incisors diagnosed with different severities of MIH. Resin infiltration was the first choice for mild cases in all three groups. Resin-based composite restorations and microabrasion were commonly chosen as the preferred management approaches by pediatric dentists and restorative dentists/prosthodontics for mild cases. In severe cases, resin-based composite restorations were the most preferred choice for all the groups. Indirect restorations, RMGI, and case referral were also common choices for all groups in severe cases. In all three groups, the favoured management options were predominantly conservative in the mild incisor case, but they were primarily interventional and restorative in the severe case. In both cases, etch-bleach-seal and partial veneers were among the least chosen management approaches in all groups. None of the participating dentists chose “no treatment” for the severe case.

Fig. 2.

Responses of participating dentists to the third and fourth cases of MIH. MIH: Molar incisor hypomineralization; FV: Fluoride varnish; FS: Fissure sealant; MicroAb: Microabrasion; EBS: Etch-bleach-seal; RI: Resin infiltration; RBC: Resin-based composite restoration; GI: Conventional glass ionomer; RMGI: Resin-modified glass ionomer; ZOE: Zinc oxide eugenol; IRM: Interim restorative material; PV: Partial veneer; Indirect: Indirect restorations including inlays, onlays, porcelain-fused to metal crowns, zirconia crowns, or E-Max crowns; No ttt: no treatment, Referral: referral to other specialties

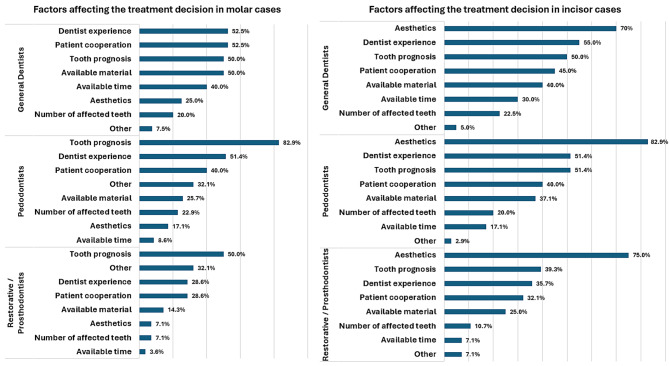

When the participating dentists were asked about the factors they considered when making their treatment decisions, tooth prognosis and dentist experience were among the top-cited factors influencing the selection of treatment in cases of permanent first molars diagnosed with MIH, followed by patient cooperation. However, in cases of permanent incisors diagnosed with MIH, aesthetics was the most considered factor, followed by experience, patient cooperation, and tooth prognosis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Factors considered by the participating dentists when making their treatment decision

Discussion

This study investigated variations in treatment decisions made by dentists from different specialties in Saudi Arabia when treating permanent first molars and incisors affected by varying degrees of MIH. general dentists and restorative dentists/prosthodontics were reported to prefer resin-based composite restoration. In contrast, pediatric dentists considered SSCs as the preferred modality. Resin infiltration was the most common treatment chosen for permanent anterior teeth with mild MIH but resin-based composite restorations were predominantly chosen for severe cases. Tooth prognosis, dentist experience and aesthetic were among the top cited factors influencing the decision of preferred treatment option.n

In this study, it was apparent that MIH-affected teeth were managed inconsistently within and between specialties across the sample. Resin-based composite restoration was the material preferred by general dentists and restorative dentists/prosthodontics for permanent first molars affected by MIH. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies in which resin-based composites were the most preferred dental treatment as well among the participating dentists [19–22]. However, it does not agree with the results of Crombie et al., who found glass ionomer cement (GIC) to be the preferred material for managing teeth with MIH [23]. It also disagrees with Gómez-Clavel et al., as RMGI was the most selected treatment by general practice dentists while GIC was selected by dentists of other specialties [24]. On the other hand, in this study pediatric dentists preferred SSCs as the treatment of choice for managing permanent first molars affected by MIH with varying degrees of severity, consistent with the recent surveys conducted in the United Arab Emirates and Norway [17, 25]. This disagrees with Gómez-Clavel et al., where pediatric dentists preferred GIC [24]. While, in this study, a limited number of general dentists preferred placing SSCs on the permanent first molars, and no restorative/prosthodontists selected this treatment option. This could be attributed to the extensive training on MIH-affected teeth in pediatric dentistry postgraduate residency programs, and the lack of such training in undergraduate programs. A previous study investigated the attitudes and preferred treatment choices for permanent first molars diagnosed with mild MIH among Swedish dentists, and fluoride varnish (FV) application was the most common treatment choice selected by general and pediatric dentists [26]. This disagrees with the findings of this study, in which only 10% of pediatric dentists and 22.2% of general dentists considered FV application as a treatment option for permanent first molars with mild MIH.

The challenge in managing MIH-affected permanent first molars using direct adhesive restorations arises from the poor adhesion with resin-based composites. Certain strategies have been suggested to improve the bond strength, such as removing all MIH-affected enamel and placing the cavity margin on sound enamel, leading to more extensive cavity preparation [27]. Therefore, SSCs have been recommended as interim full-coverage restorations in children for the treatment of MIH-affected permanent first molars to provide a higher survival rate [28]. Although extraction of first permanent molars with severe MIH in children between the ages of 6 and 11 years is recommended by the Swedish National Guidelines and the Royal College of Surgeon of England Clinical Guidelines as a cost-effective alternative in some severe cases [26]. However, extraction was not chosen in the current study by any of the responders. There is limited evidence on the ideal management of MIH-affected teeth in children [29, 30]. The treatment options depend on multiple factors, including the severity of the defect, tooth restorability, patient age, and level of patient cooperation [29, 31]. In the current survey, a high percentage of general dentists considered dentists’ experiences (52.5%) and child cooperation (52.5%) as important factors influencing treatment decisions for MIH-affected permanent first molars. This may reflect their limited training in managing MIH-affected teeth and child behavior management. This agrees with the findings of Alanzi et al., who reported that children’s behavior and insufficient training are barriers to managing MIH [19]. Meanwhile, 82.9% of pediatric dentists and 50% of restorative dentists/prosthodontists agreed that tooth prognosis was the main factor in their decision to treat MIH-affected permanent first molars [19, 32].

Resin infiltration was the most preferred treatment approach for permanent incisors with mild MIH. Simultaneously, resin-based composite was the most frequently chosen restorative material for the permanent anterior with MIH selected by all respondents. This is in partial agreement with Alanzi et al., who reported that bleaching and sealing with low-viscosity resin (ICON ®) was the most preferred method by all dental specialists, including pediatric dentists in mild cases of MIH-affected permanent incisors [19]. Furthermore, 37.5% of pediatric dentists and 32.1% of restorative/prosthodontists chose resin-based composites, followed by microabrasion as the treatment option for permanent anterior incisors affected by MIH. In the current study, aesthetics was the main factor influencing the treatment decisions for MIH-affected permanent incisors selected by all participating dentists. This agrees with a survey conducted by Crombie et al. of the Australian and New Zealand Society of Pediatric Dentistry members [23].

This survey study had some limitations. First, the small sample size, which was a result of the challenges in reaching all dentists in Saudi Arabia. To overcome this limitation, the questionnaire was distributed via multiple electronic platforms such as email and WhatsApp. Emails and WhatsApp, are considered as a primary communication platform in Saudi Arabia, facilitating diversity and inclusion of a large number of participants. WhatsApp users are approximately 28 million in the country, accounting for over three-quarters of the population therefore it has been used as a main distribution method in this study [33]. In addition, the sample size may be considered small which may limit the generalization of the results to the dentist population in Saudi Arabia.

This distribution method may limit the generalizability of the results. Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study established baseline data on treatment variations among dental specialties for MIH-affected teeth in Saudi Arabia. They established baseline data on treatment variations among dental specialties for MIH-affected teeth in Saudi Arabia.

When dentists in Mexico City’s metropolitan area were asked about the challenges in managing MIH, 86% identified limited training as the primary issue. Furthermore, when questioned about the necessity of addressing the aetiology, diagnosis, and/or treatment of MIH, treatment was deemed the most necessary by the highest percentage of respondents [24].

This information is crucial for understanding the current landscape of MIH treatment and will pave the way for dental educators to review, modify and implement essential curricular updates to the dental curriculum with more emphesis on the diagnosis and mangment of MIH affected teeth and addressing the training requirements of professionals in different specialty.

Conclusion

The survey showed that there is a wide variety in managing cases of MIH according to tooth severity and category of the permanent tooth (anterior/posterior) among different dental specialties in Saudi Arabia. Direct restorations using composite restorations were the most common treatment option selected in most cases and between all specialties, and pediatric dentists preferred using SCC in severe posterior cases and resin infiltration in mild anterior cases, followed by microabrasion as the second most preferred option.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully extend our thanks to the dentists for taking the time to participate in this study. The English language was edited by Editage Acadmic editing services.

Abbreviations

- EBS

Etch-bleach-seal

- FS

Fissure sealant

- FV

Fluoride varnish

- GI

Conventional glass ionomer

- IRM

Interim restorative material

- MIH

Molar incisor hypomineralization

- No ttt

No treatment

- PEB

Post-eruptive enamel breakdown

- PV

Partial veneer

- RBC

Resin-modified composite restoration

- RI

Resin infiltration

- RMGI

Resin-modified glass ionomer

- SSC

Stainless steel crown

- ZOE

Zinc oxide eugenol

Author contributions

S.B. contributed to concept or design of the work, drafting the manuscript and revised it critically. SNA contributed to the concept or design of the work, data collection, drafting the manuscript and revised it critically. R.A. and SAA contributed to data collection, writing the manuscript. O.F. contributed to the concept or design of the work, interpretation of data and analysis and revising the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this project.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this cross-sectional electronic survey was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Dentistry (approval number: 173-12-20). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Neither directly nor indirectly identifiable personal data were registered in the project. All the participating dentists consented to participate in the survey/ questionnaire study using Google Forms electronically.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Weerheijm KL, Jälevik B, Alaluusua S. Molar-incisor hypomineralisation. Caries Res. 2001;35(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lygidakis NA, Garot E, Somani C, Taylor GD, Rouas P, Wong FS. Best clinical practice guidance for clinicians dealing with children presenting with molar-incisor-hypomineralisation (MIH): an updated European academy of paediatric dentistry policy document. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry 2022 Feb 20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Navarro NP, Buldur B. Worldwide prevalence of molar-incisor hypomineralization: A. Contemp Pediatr Dent. 2024;5(1):15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allazzam SM, Alaki SM, El Meligy OA. Molar incisor hypomineralization, prevalence, and etiology. Int J Dent. 2014;2014(1):234508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizk H, Al-Mutairi MM, Habibullah MA. The prevalence of molar-incisor hypomineralization in primary schoolchildren aged 7–9 years in Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. J Interdisciplinary Dentistry. 2018;8(2):44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hammad NS, Al-Dhubaiban M, Alhowaish L, Bello LL. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of molar-incisor-hypomineralization in school children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Sci Clin Invent. 2018;5(3):3570–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva MJ, Scurrah KJ, Craig JM, Manton DJ, Kilpatrick N. Etiology of molar incisor hypomineralization–A systematic review. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44(4):342–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negre-Barber A, Montiel-Company JM, Catalá-Pizarro M, Almerich-Silla JM. Degree of severity of molar incisor hypomineralization and its relation to dental caries. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weerheijm KL. Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH). Eur J Pediatr Dentistry. 2003;4:115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagrell TG, Dietz W, Jälevik B, Norén JG. Chemical, mechanical and morphological properties of hypomineralized enamel of permanent first molars. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68(4):215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagarde M, Vennat E, Attal JP, Dursun E. Strategies to optimize bonding of adhesive materials to molar-incisor hypomineralization‐affected enamel: A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2020 Jul;30(4):405–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Leppaniemi A, Lukinmaa PL, Alaluusua S. Nonfluoride hypomineralizations in the permanent first molars and their impact on the treatment need. Caries Res. 2001;35(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mejàre I, Bergman E, Grindefjord M. Hypomineralized molars and incisors of unknown origin: treatment outcome at age 18 years. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2005;15(1):20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopperud SE, Pedersen CG, Espelid I. Treatment decisions on Molar-Incisor hypomineralization (MIH) by Norwegian dentists–a questionnaire study. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagelsir A, Dean JA, Eckert GJ, Martinez-Mier EA. US pediatric dentists’ perception of molar incisor hypomineralization. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40(4):272–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva MJ, Alhowaish L, Ghanim A, Manton DJ. Knowledge and attitudes regarding molar incisor hypomineralisation amongst Saudi Arabian dental practitioners and dental students. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry. 2016;17:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuollet E, Tseveenjav B, Furuholm J, Waltimo-Sirén J, Valen H, Mulic A, Ansteinsson V, Uhlen MM. Restorative material choices for extensive carious lesions and hypomineralisation defects in children: a questionnaire survey among Finnish dentists. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2020 Mar 1;21(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Alqahtani AS, Alqhtani NR, Gufran K, Aljulayfi IS, Alateek AM, Alotni SI, Aljarad AJ, Alhamdi AA, Alotaibi YK. Analysis of trends in demographic distribution of dental workforce in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022(1):5321628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alanzi A, Faridoun A, Kavvadia K, Ghanim A. Dentists’ perception, knowledge, and clinical management of molar-incisor-hypomineralisation in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagheri R, Ghanim A, Azar MR, Manton DJ. Molar incisor hypomineralisation: discernment a group of Iranian dental academics. J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol. 2014;3(1):21–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussein AS, Ghanim AM, Abu-Hassan MI, Manton DJ. Knowledge, management and perceived barriers to treatment of molar-incisor hypomineralisation in general dental practitioners and dental nurses in Malaysia. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry. 2014;15:301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall A, Leith R. A questionnaire study on perception and clinical management of molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) by Irish dentists. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry. 2020 Dec;21:703–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Crombie FA, Manton DJ, Weerheijm KL, Kilpatrick NM. Molar incisor hypomineralization: a survey of members of the Australian and new Zealand society of paediatric dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2008;53(2):160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gómez-Clavel JF, Sánchez-Cruz FY, Santillán-Carlos XP, Nieto-Sánchez MP, Vidal-Gutiérrez X, Pineda ÁE. Knowledge, experience, and perception of molar incisor hypomineralisation among dentists in the metropolitan area of Mexico City: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2023 Dec 19;23(1):1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Dastouri M, Kowash M, Al-Halabi M, Salami A, Khamis AH, Hussein I. United Arab Emirates dentists’ perceptions about the management of broken down first permanent molars and their enforced extraction in children: a questionnaire survey. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry. 2020 Feb;21:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hajdarević A, Čirgić E, Robertson A, Sabel N, Jälevik B. Treatment choice for first permanent molars affected with molar-incisor hypomineralization, in patients 7–8 years of age: a questionnaire study among Swedish general dentists, orthodontists, and pediatric dentists. Eur Archives Pediatr Dentistry. 2024 Feb;25(1):93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Linner T, Khazaei Y, Bücher K, Pfisterer J, Hickel R, Kühnisch J. Comparison of four different treatment strategies in teeth with molar-incisor hypomineralization‐related enamel breakdown–A retrospective cohort study. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2020 Sep;30(5):597–606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Seale NS, Randall R. The use of stainless steel crowns: a systematic literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(2):145–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor GD, Pearce KF, Vernazza CR. Management of compromised first permanent molars in children: cross-Sectional analysis of attitudes of UK general dental practitioners and specialists in paediatric dentistry. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2019;29(3):267–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elhennawy K, Schwendicke F. Managing molar-incisor hypomineralization: A systematic review. J Dent. 2016;55:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkhalaf R, Neves AD, Banerjee A, Hosey MT. Minimally invasive judgement calls: managing compromised first permanent molars in children. Br Dent J. 2020 Oct;229(7):459–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Skaare AB, Houlihan C, Nybø CJ, Brusevold IJ. Knowledge, experience and perception regarding molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) among dentists and dental hygienists in Oslo, Norway. European archives of paediatric dentistry. 2021 Oct;22(5):851–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Insight GM. Saudi Arabia Social Media Statistics 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.