Abstract

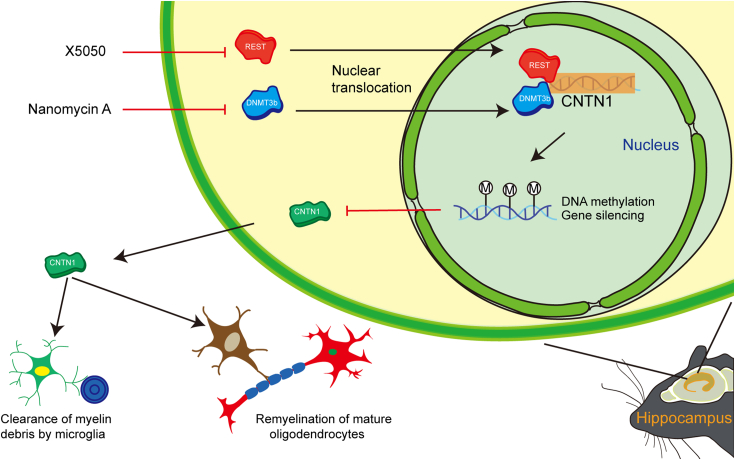

The remyelination process within the diabetes mellitus (DM) brain is inhibited, and dynamic interactions between DNA methylation and transcription factors are critical for this process. Repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor (REST) is a major regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation, and the role of REST on DM remyelination remains to be investigated. Here, we investigated the effects of REST and DNA methylation on DM remyelination and explored the underlying mechanisms. In this study, using a diabetic mouse model, we found that myelin damage preceded neuronal damage and caused cognitive impairment in DM mice. Inhibition of REST by X5050 and DNMT3b by Naomycin A promoted myelin regeneration in the hippocampus and ameliorated cognitive deficits in DM mice. In addition, CpA methylation of the RE-1 locus of the CNTN1 gene was able to increase the binding capacity of REST. We also observed that CNTN1 promotes oligodendrocyte maturation, facilitates the ratio of microglia to pro-regenerative phenotypes as well as enhances the ability of microglia to remove myelin debris. Our findings suggest that REST and DNMT3b expression inhibit CNTN1 expression and exacerbate myelin damage. This mechanism of gene silencing may be associated with DNMT3b-mediated CpA methylation of the REST binding site in the promoter region of the CNTN1 gene. We also identified the role for CNTN1 in promoting oligodendrocyte precursor cell maturation and myelin debris removal during remyelination.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, demyelination, CNTN1, oligodendrocyte, REST, DNA methylation

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and glycosuria. It has become a worldwide epidemic and has one of the highest incidence rates of all chronic diseases. The International Diabetes Federation recently revealed that more than 463 million people have diabetes, and the number of cases is expected to increase to 700 million by 2045 (1).The increasing prevalence of diabetes and secondary complications has created a large economic burden worldwide. There is increasing evidence from studies in both animal models and humans with DM demonstrating that diabetes predisposes individuals to diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction (DACD), which leads to dementia (2, 3, 4). A decline in working memory, information processing, attention, and executive function has been observed in patients with DACD irrespective of age (5, 6). DACD can be mild to moderate and can severely impair daily functioning, adversely affecting quality of life (7).

Demyelination leads to impaired transmission of nerve impulses, accompanied by neurodegeneration and impairment of spatial learning and memory (8, 9, 10). Demyelination is increased in patients with DACD, although the reasons for this are not clear. It may be related to increased neuronal damage, injury to the BBB allowing for the entry of circulating antibodies into the central nervous system (CNS), particularly demyelinating antibodies such as anti-myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies (11, 12, 13). This entry leads to enhanced inflammatory responses and the dislocation of iron from binding sites, which triggers the formation of reactive oxygen species (14, 15, 16, 17, 18). Remyelination, the novel formation of myelin sheaths around demyelinated axons by newly differentiated oligodendrocytes, can efficiently occur following CNS demyelination. DM can lead to delayed remyelination by oligodendrocytes (19). To date, the factors underlying inadequate remyelination and repair are poorly understood, and reparative therapies to benefit patients with DM have yet to be developed.

The dynamic interplay between DNA methylation and transcription factor binding in regulating spatiotemporal gene expression is critical for remyelination, and there is a research gap regarding this topic in DACD. DNA methylation in oligodendrocytes (OLs) is dynamically regulated during development as well as in response to physiological and pathological stimuli (20, 21). DNA methylation is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b. Although DNMT1 is primarily responsible for the maintenance of DNA methylation, DNMT3a and DNMT3b are involved in de novo methylation patterns during cellular differentiation (22, 23). However, how DNMTs target specific genetic regions remains unclear (24). DNMTs can bind to transcription factors or components of repressor complexes to target DNA for methylation. Repressor element 1 (RE1)-silencing transcription factor (REST; also known as NRSF [Neuron restrictive silencer factor]) suppresses the expression of neuronal genes in nonneuronal cells, but its functions have recently been shown to be more diverse (25). Aberrant REST expression and function have been implicated in the development of diverse disorders, including cancer (26), neurodegeneration (27), and neurodevelopmental diseases (28). REST regulates neuronal differentiation in embryonic and neural stem cells (29), and recent studies have confirmed the important role of REST in regulating OL differentiation (30, 31, 32); however, its role in the demyelinating lesion spectrum of OLs is unclear. It has been shown that REST strongly represses gene expression when its binding sites, RE1 motifs, exhibit increased DNA methylation (29, 33). Stadler and collaborators demonstrated that the inhibition of REST expression in embryonic stem cells is associated with increased DNA methylation in its target regions, while the forced expression of REST in a knockout model restored the unmethylated state (34). The exact mechanism by which REST modulates DNA methylation at RE1 sites and neighboring regions is not clear; however, there may be an interplay between REST and DNA methylation machinery.

The remaining genes of the OL lineage are a unique set of target genes that encode factors that play a role in shaping early OL development and terminal differentiation as well as progressive maturation. For example, Sema3a is a guidance cue that directs OL migration; Mobp is an essential myelin protein; and Contactin-1 (CNTN1) is an immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecule critical for promoting OL maturation (35, 36, 37). CNTN1 expression has been detected in retinal, spinal cord, cerebral cortex, hippocampal, and cerebellar tissues as well as in OLs (38, 39, 40, 41). CNTN1 also plays important roles in the hippocampus, thereby augmenting synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and memory in adult mice (42, 43). CNTN1 overexpression leads to an inhibition of neurogenesis (44, 45), it is also associated with the promotion of OL differentiation (46), which are associated with Notch pathway activation. However, the role of CNTN1 in demyelinating lesions remains understudied.

The regulation of abnormal DNA methylation and transcription factor patterns is a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of diabetes-related demyelination. We hypothesized that CNTN1 expression is regulated by REST and DNA methylation and explored the effects of CNTN1 on myelin regeneration and glial cells in the hippocampus of diabetic mice.

Result

Hippocampal demyelination and cognitive decline in DM mice

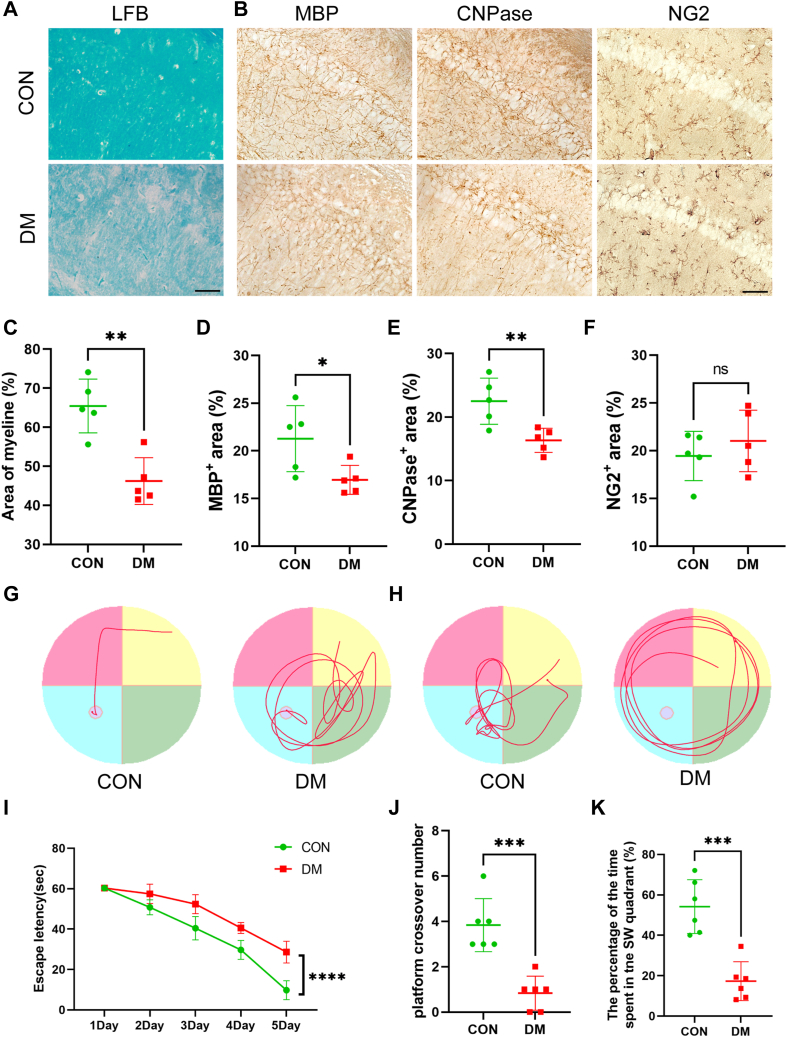

Myelin acts as an electrical insulator, facilitating conduction in axons. Thus, alterations in myelin functional and/or structural changes are likely to result in changes in cognitive function. Therefore, we first investigated demyelination and cognitive function in the brains of diabetic mice 4 weeks after STZ injection. Therefore, immunohistochemical and LFB staining were used to evaluate the degree of myelin loss induced by DM (Fig. 1, A and C). At 4 weeks after STZ injection, diabetic mice exhibited myelin loss in the CA1 region. Compared with those in the control group, the positive expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) and 2,3-cyclic nucleotide 3-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) in the CA1 regions of the hippocampi of DM mice was significantly reduced and disrupted according to histochemical staining (Fig. 1, B, D and E). Interestingly, the number of OL precursor cells (OPCs, NG2+ cells) did not decrease (Fig. 1, B and F). This finding suggests that the impaired myelin regeneration seen in DM mice may be due to the inhibition of OPC maturation.

Figure 1.

DM resulted in cognitive impairment and demyelination in mice.A and C, representative LFB staining in different groups (A) and quantification of myelinated areas (C). Two-tailed Student’s t tests were used for analysis, N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. B, representative images of MBP, CNPase and NG2 expression in different groups. Two-tailed Student’s t tests were used for analysis, N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. D–F, quantification of the protein expression of MBP (D), CNPase (E) and NG2 (F) in the different groups. N = 5/group. G, representative swimming route traces of mice from different groups. H, representative images of swimming route traces of mice from different groups after removal of the platform. I, in the MWM experiment, the escape latency of the mice during the acquisition test was recorded (N = 6/group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used for analysis. J, quantitative analysis of the original platform location-crossing frequency within 60 s. N = 6/group. K, statistical analysis of the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial across all groups. N = 6/group. One-tailed Student’s t tests were used for analysis. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Then, the MWM test was conducted to explore STZ-induced spatial and working memory impairment. First, STZ induced spatial memory deficits in diabetic mice as evidenced by increased time spent finding the hidden platform during the learning process (Fig. 1, G and I). The results of the spatial exploration test showed that the diabetic mice spent less time in the target quadrant and made fewer platform crossings (Fig. 1, H, J and K). Taken together, these data suggest that myelin loss and cognitive defects are aggravated in the hippocampal CA1 regions of diabetic mice 4 weeks after STZ injection.

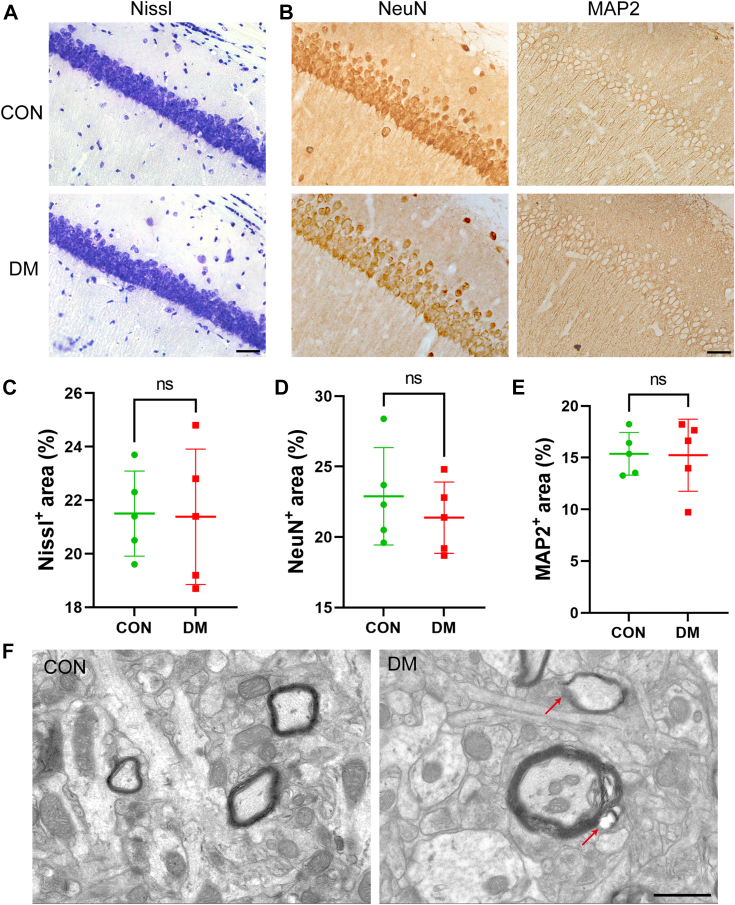

Myelin lipid loss precedes changes in nerve structure

We observed neuronal structural and functional changes in mice 4 weeks after STZ injection by Nissl and immunohistochemical staining. There was no significant difference in Nissl staining positivity between the CON and DM groups (Fig. 2, A and C), and immunohistochemical staining for Neun and MAP2 expression showed no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2, B, D and E). Finally, we assessed myelin ultrastructure via EM in the hippocampi of control and diabetic mice. Consistent with a reduction in the abundance of myelin signature lipids, cross-sectional EM revealed a significant decrease in myelin thickness and a decrease in myelin integrity (Fig. 2, F). Conversely, the integrity of hippocampal axons was not disrupted. The abovementioned results illustrate that the cognitive deficits observed in DM mice 4 weeks after STZ injection are mainly related to myelin damage rather than to neuronal structure and function changes.

Figure 2.

Disruption of myelin but not axonal nerve structure in DM mice.A and C, representative Nissl staining (A) of the CON and DM groups and quantification of myelinated areas (C). N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. B, representative images of NeuN and MAP2 expression in the CON and DM groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. D and E, quantification of the protein expression of NeuN (D) and MAP2 (E) in the different groups. Two-tailed Student’s t tests were used for analysis. F, representative cross-sectional EM images of myelinated neurons in the hippocampus. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 1 μm.

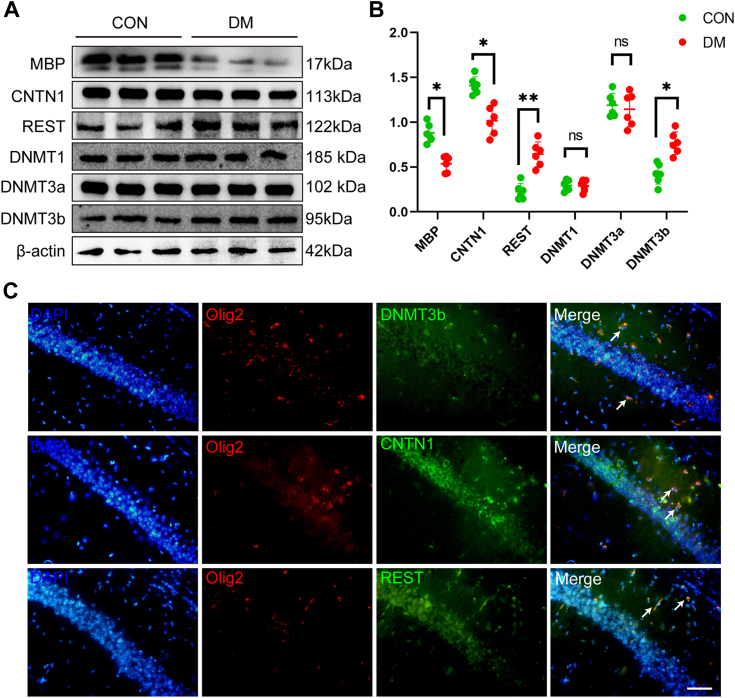

Increased hippocampal REST and DNMT3b expression in diabetic mice

REST plays an important role in the differentiation and maturation of OL lineages, and we speculate that changes in REST expression may inhibit OPC maturation. Because DNMTs are considered potential REST cofactors, we next examined the expression of MBP, CNTN1, REST, and DNMTs (DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b) and found that the expression of REST increased in conjunction with that of DNMT3B and showed a trend opposite to that of MBP, whereas the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3a was relatively stable (Fig. 3, A and B). We then explored whether CNTN1, REST, and DNMT3b expressions were colocalized with OLs. Hippocampal slices were co-immunostained with anti-CNTN1, anti-REST, anti-DNMT3b, and anti-Olig2 antibodies. Representative images showed that expression of CNTN1, REST, and DNMT3b was colocalized with Olig2-positive cells (Fig. 3, A and C).

Figure 3.

Decreased expression of MBP and CNTN1 and increased expression of REST and DNMT3b in the hippocampus of DM mice.A, representative Western blot images of MBP, CNTN1, REST, DNMT1, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, and β-actin protein expression across different groups. B, quantification of the protein expression levels of MBP, CNTN1, REST, DNMT1, DNMT3, and DNMT3b in the CON and DM groups. N = 5/group. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. C, representative images of immunofluorescence in the CA1 region of the DM mouse hippocampus, where Olig2-labelled OLs were double-labeled using fluorescence to indicate colocalization with CNTN1, REST, and DNMT3b. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

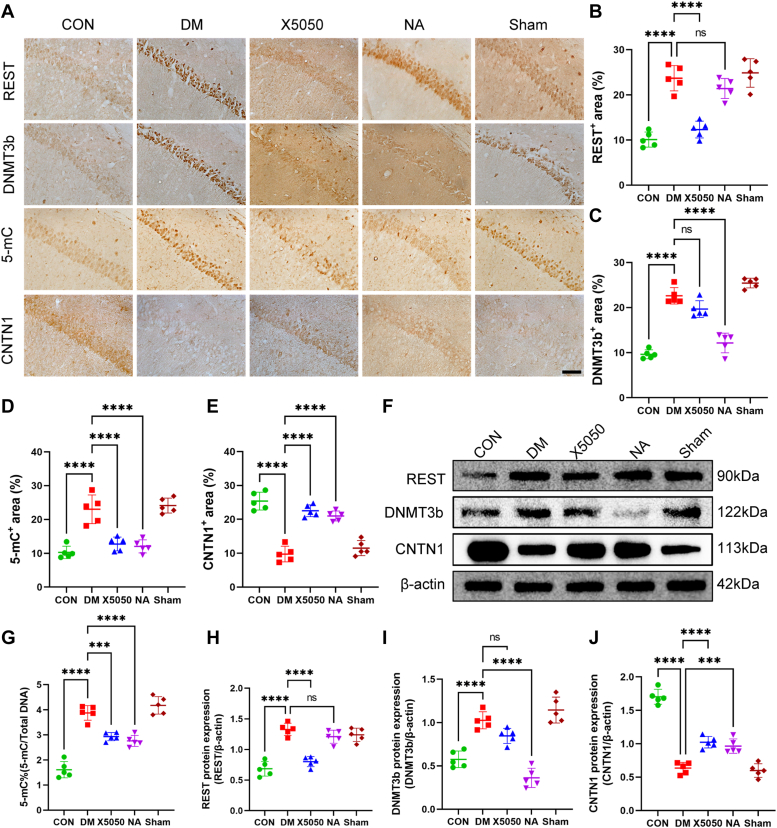

Inhibition of either REST or DNMT3b increases hippocampal CNTN1 expression in DM mice

To explore the relationship between elevated REST expression and elevated global DNA methylation levels and myelin damage, we administered lateral ventricular injections of x5050 to diabetic mice (a REST protein inhibitor) and nanomycin A (a DNMT3B protein inhibitor). Two weeks after inhibitor injection, immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect the distribution of REST, DNMT3b, and CNTN1 expression in the hippocampal CA1 regions of treated mice. As expected, CNTN1 expression in the CA1 region showed an opposite trend to that of REST and DNMT3b, and a reduction in the nuclear translocation of REST and DNMT3b was observed (Fig. 4, A–E). The WB results also showed that X5050 reduced REST expression and that nanomycin A reduced DNMT3b expression (Fig. 4, H and I). However, X5050 does not completely inhibit DNMT3b expression, and nanomycin A does not completely inhibit REST expression. Moreover, reductions in both REST and DNMT3b expression led to an increase in the expression of CNTN1 (Fig. 4J). Interestingly, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and DNA methylation level detection revealed that DNMT3b exhibited reduced total methylation levels in the NA group, as well as in the X5050 group (Fig. 4, D and G).

Figure 4.

X5050 administration inhibited REST expression. Nanomycin A administration inhibited the expression of DNMT3b, alleviated the reduction in CNTN1 expression in the brains of DM mice and suppressed the increase in 5 mC levels in DM mice. A, representative images of REST, DNMT3b, 5-mC and CNTN1 expression staining in CA1 from different groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. B–E, quantification of REST (B), DNMT3b (C), 5-mC (D), and CNTN1 (E) protein expression in the different groups. N = 5/group. G, total DNA methylation levels in different groups. N = 5/group. F, Representative Western blot images showing REST, DNMT3b, CNTN1, and β-actin expression in the different groups. H–J, quantification of REST (H), DNMT3b (I), and CNTN1 (J) protein expression in the different groups. N = 5/group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

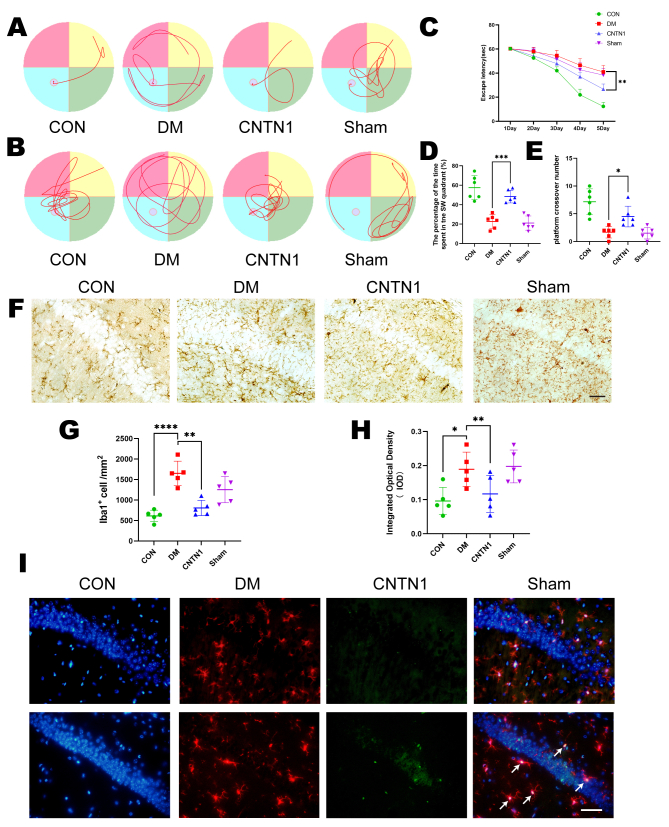

Elevation in CNTN1 expression by inhibiting REST and DNMT3b expression ameliorates myelin damage and alleviates cognitive dysfunction in DM mice

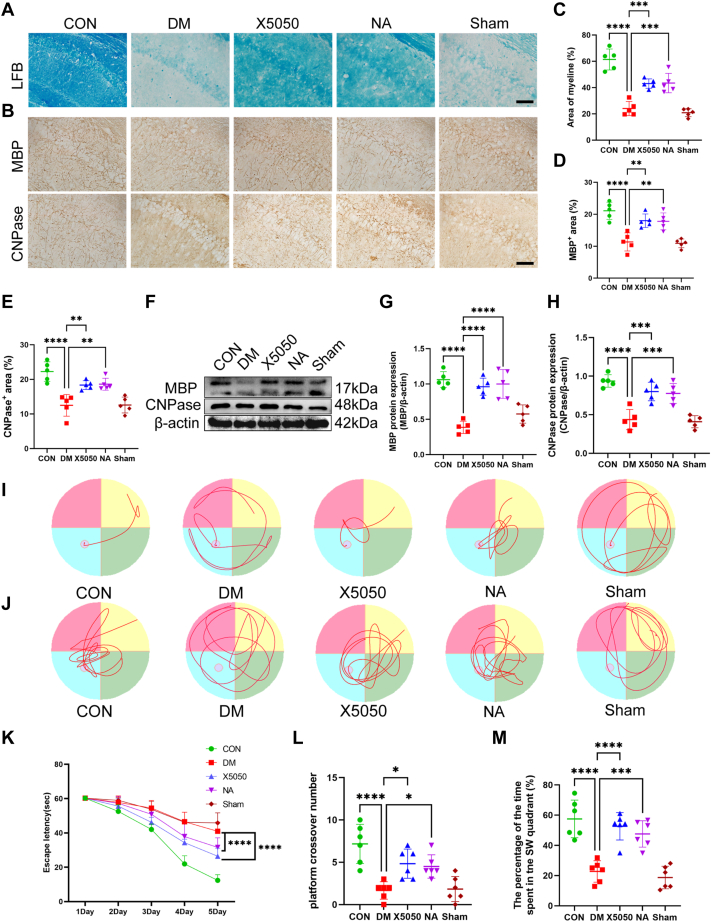

CNTN1 expression was increased by decreasing both REST and DNMT3b expression; we then examined the effects of elevated CNTN1 expression on myelination and cognitive function. Representative images of immunohistochemical (MBP and CNPase) and LFB staining showed that compared with DM mice, X5050 and nanomycin A administration partially restored damaged myelin sheaths (Fig. 5, A–E). WB analysis also verified this trend (Fig. 5, F–H). According to the MWM test, X5050 and nanomycin A administration also partially repaired DM-induced cognitive deficits, as evidenced by an increase in the latency to reach the target plateau, a decrease in the time spent in the target plateau quadrant, and a decrease in the frequency of entry into the plateau region in the X5050 and NA groups compared to the DM group (Fig. 5, I–M). These results suggest that the administration of X5050 and nanomycin A promotes myelin regeneration in DM, which is partly related to the expression of CNTN1 following the inhibition of REST and DNMT3b.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of REST and DNMT3b expression ameliorates myelin damage and alleviates cognitive dysfunction in DM mice.A and C, representative LFB staining of the CA1 region in different groups (A) and quantification of myelinated areas (C). N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. B, representative images of MBP and CNPase expression staining in different groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. D and E, quantification of the protein expression of MBP (D) and CNPase (E) in the different groups. N = 5/group. F, Representative Western blot images of MBP, CNPase and β-actin expression staining in the different groups. G and H, quantification of the protein expression of MBP (G) and CNTN1 (H) in the different groups. N = 5/group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. I, representative swimming route traces of mice from different groups. J, representative images of swimming route traces of mice from different groups after removal of the platform. K, in the MWM experiment, the escape latency of the mice during the acquisition test was recorded (N = 6/group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used for analysis. L, Quantitative analysis of the frequency of original platform location-crossing within 60 s. N = 6/group. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. M, Statistical analysis of the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial among the groups. N = 6/group. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

CNTN1 expression silencing depends on the nonCpG methylation of CNTN1-RE1 by DNMT3B

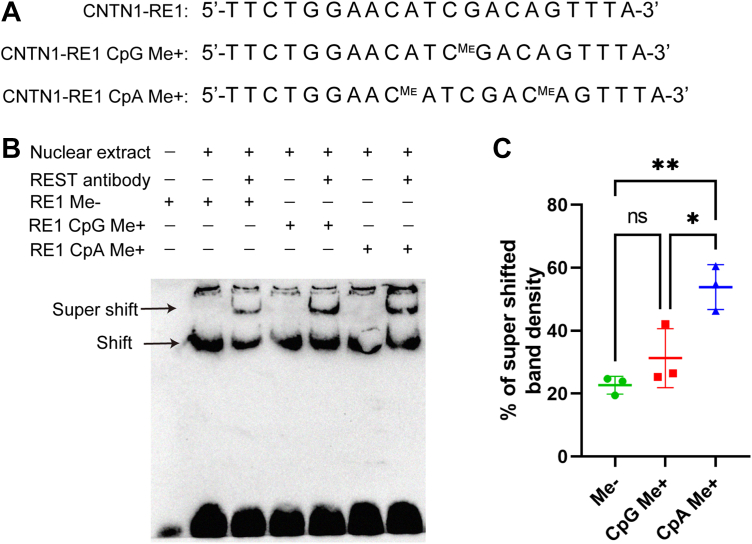

We then generated CNTN1-RE1s with different cytosine methylation states and tested the differences in REST binding by EMSA using nuclear extracts from hippocampal cells. CpA methylation increased REST binding, while CpG methylation had no or limited effect on REST binding (Fig. 6, A–C).

Figure 6.

CpA methylation of the CNTN1-RE1 facilitates REST binding.A, the biotinylated CNTN1-RE1 with varied CpG or CpA methylation (Me+) in probes used for EMSA. B, representative blot of EMSA results using hippocampal nuclear extracts and biotinylated CNTN1-RE1. C, Percentage (%) of supershifted bands/total conjugates (N = 3/group), calculated using Student's t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

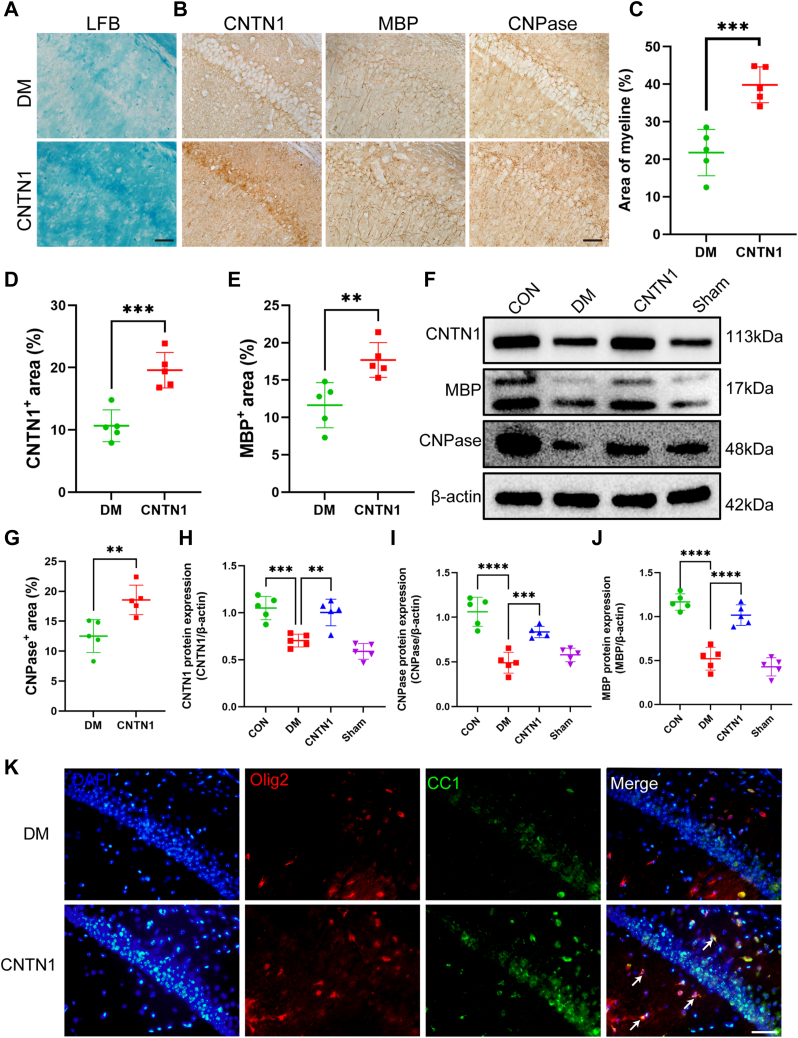

CNTN1 improves hippocampal demyelination in DM mice, which is associated with promoting OL maturation

In a focal lysolecithin-induced demyelination model, remyelination was characterized by the overexpression of CNTN1, which may induce oligodendroglial maturation through Notch activation, thus promoting remyelination. Therefore, we observed myelination and cognitive function changes by injecting recombinant CNTN1 protein into the lateral ventricles of diabetic mice. Representative images of immunohistochemical and LFB staining revealed an increase in the myelinated areas and integrity in the CNTN1-administered group compared to those in the diabetic group (Fig. 7, A–E and G). The MWM results showed that CNTN1-administered diabetic mice found the hidden platforms in a shorter period, stayed in the target quadrant longer, and traversed the platform more often during learning (Fig. S1, A–E). The Western blotting results showed a concomitant increase in MBP and CNPase expression after increasing CNTN1 expression (Fig. 7, F and H–J). Moreover, by Olig2 and CC1 immunolabelling, we observed an increase in the area of CC1-positive OLs, a marker of mature OLs, in CNTN1-administered mice compared with those in DM mice (Fig. 7K).

Figure 7.

Injection of CNTN1 recombinant protein promotes OL maturation and improves hippocampal demyelination in DM mice.A and C, representative LFB staining of CA1 in different groups (A) and quantification of myelinated areas (C). N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. B, representative images of CNTN1, MBP and CNPase expression in different groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. D, E, and G, quantification of the protein expression of CNTN1 (D), MBP (E) and CNPase (G) in the different groups. N = 5/group. F, representative Western blot images showing CNTN1, MBP, CNPase and β-actin expression across the different groups. H–J, quantification of the protein expression of CNTN1 (H), MBP (I), and CNTN1 (J) across the different groups. N = 5/group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. K, immunofluorescence double labelling of Olig2 and CC1 expression across different groups, with arrows indicating Olig2+ and CC1+ cells. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

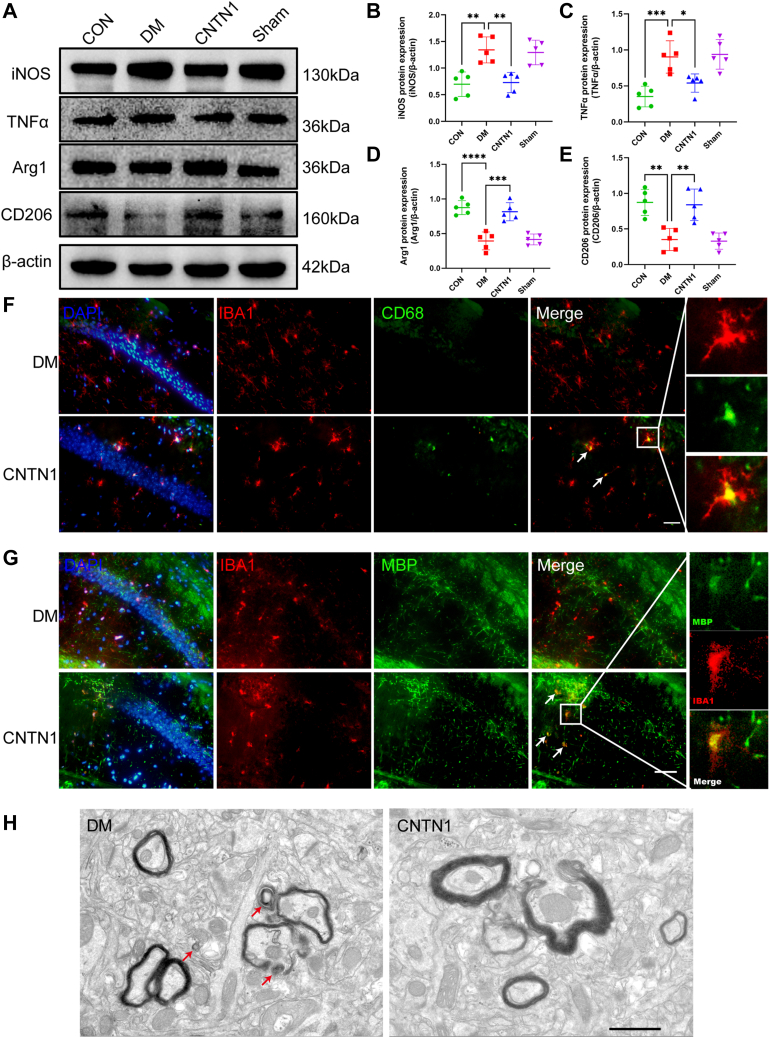

CNTN1 promotes microglial polarization to the M2 phenotype and facilitates myelin fragment clearance

Considering that myelin regeneration requires phagocytosis and the pro-regenerative functions of microglia, we subsequently explored the effects of CNTN1 expression on microglial activation and phagocytosis. Microglial activation can be divided into proinflammatory, damaging M1 phenotype polarization and anti-inflammatory, regeneration-promoting M2 phenotype polarization. To determine the effect of CNTN1 on M2 polarization, we first examined the expression levels of the M1/M2 microglia markers iNOS and arg1. Compared with that in diabetic mice, the expression level of iNOS in the hippocampal regions of diabetic mice injected with recombinant CNTN1 was lower, and the expression level of arg1 in the hippocampal region was greater (Fig. 8, A–E). Next, we observed the morphology of microglia and the changes in ARG1 expression. Immunohistochemical staining showed that in the DM group, the processes of microglia became shorter and thicker, the cell bodies enlarged, and the average optical density values increased, while treatment with CNTN1 improved the changes in microglia caused by diabetes (Fig. S1, F–H). In addition, by immunolabeling Iba1 and ARG1 expression, we observed an increase in the number of ARG1-positive microglia in mice treated with CNTN1 compared to DM mice (Fig. S1I). These data suggest that CNTN1 promotes microglial M2 phenotype switching and enhances microglial phagocytosis. Collectively, the above results show that CNTN1 can promote M2 polarization, which may induce an environment allowing for the maturation of OLs.

Figure 8.

Injection of CNTN1 promotes microglial polarization to the M2 phenotype and facilitates myelin fragment clearance in DM mice.A, representative Western blot images showing iNOS, TNFɑ, Arg1, CD206, and β-actin expression across the different groups. D–F, quantification of the protein expression of iNOS (B), TNF-ɑ (C), Arg1 (D), and CD206 (E) across the different groups. N = 5/group. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for analysis. F, Immunofluorescence double labelling of Iba1 and CD68 across different groups, with arrows indicating Iba1+ and CD68+ cells. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. G, Immunofluorescence double labelling of Iba1 and MBP across different groups, with arrows indicating Iba1+ and MBP+ cells. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 50 μm. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. H, representative cross-sectional EM images of myelinated neurons in the hippocampus. N = 5/group. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Moreover, by immunolabelling Iba1 and CD68 expression, we observed an increase in the area of CD68-positive microglia, a marker of microglial phagocytosis, in CNTN1-administered mice compared with that in DM mice (Fig. 8F). Compared to those in diabetic mice, an increasing number of MBP-immunoreactive puncta colocalized with Iba1-positive microglia after lateral ventricular injection of the CNTN1 recombinant protein (Fig. 8G). We next analyzed the hippocampi of DM mice by electron microscopy to identify myelin breakdown products. Multiple layers of myelin debris were detected in the brains of DM mice, while the amount of myelin debris was significantly reduced in the CNTN1-administered group (Fig. 8H). The above results illustrate that CNTN1 promotes the ability of microglia to remove damaged myelin and accelerates myelin regeneration.

Discussion

In this study, a diabetic mouse model was successfully established by streptozotocin injection, and the remyelination effects of REST expression and DNA methylation on diabetes were investigated. We postulated that increased REST expression and DNA methylation promote the silencing of CNTN1 and subsequently inhibit the remyelination of OLs and microglia. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that REST binding at CNTN1-RE1 is likely facilitated by DNMT3b, whose function appears to involve non-CpG methylation. Finally, we showed that the facilitating role of CNTN1 in remyelination is correlated with OPC maturation and microglial clearance (Fig. 9). This is the first study of the synergistic effects of DNA methylation and REST expression on diabetic myelin regeneration, which provides novel insight for the clinical treatment of diabetes.

Figure 9.

Graphic Abstract. A proposed mechanism outlines the inhibitory effect of REST and DNMT3b on CNTN1 in the hippocampus of diabetic mice and the role of CNTN1 in myelin regeneration.

Many studies have shown that various epigenetic phenomena, including histone modifications, microRNAs and chromatin remodelers, are required for OPC differentiation during myelination and remyelination (47, 48, 49, 50, 51). Another epigenetic marker, DNA methylation, has been shown to be particularly important for brain development and function (52, 53), but its role has been studied almost exclusively in neurons and astrocytes (54, 55, 56, 57). DNA demethylation of lineage-specific genes and subsequent transcriptional activation have been proposed to be an important step in the processes of neuronal, astrocytic, and Schwann cell differentiation (58). Therefore, we aimed to further characterize the role of DNA methylation in the oligodendroglial lineage in diabetes patients. Methylation of cytosine in CpG islands in the genome enables stable but reversible transcriptional repression and is critical for mammalian development (59, 60). Defects in the regulation of DNA methylation are associated with various neurological diseases (61, 62). For example, TET1-mediated 5hmC modification, or DNA hydroxymethylation, can modulate the process of oligogenesis and myelinogenesis through at least two critical processes—the fine-tuning of cell cycle progression for OPC proliferation and the regulation of OL homeostasis—e.g., ITPR2-mediated calcium transport—for OL myelination. One study reported global hypermethylation in the nuclei of oligodendroglial lineage cells during remyelination, similar to what has been described during developmental myelination (63, 64). Although there is controversy over the predominant roles of DNA methylation and DNA demethylation during myelin regeneration, disruption of epigenetically regulated homeostasis must impair myelin regeneration. Within the hippocampal regions of diabetic mice, we detected elevated global methylation. Interestingly, changes in DNMTs expression were spatiotemporally significant, and our results suggest that DNMT3b within the hippocampal CA1 region precedes DNMT1 and DNMT3a expression elevation and nuclear translocation. Myelin damage in the hippocampi of diabetic mice is thereby reduced, and cognitive deficits are ameliorated after DNMT3b expression inhibition by nanomycin A administration.

Similarly, in the nanomycin A group, we reduced REST expression in the hippocampi of DM mice via the REST inhibitor X5050 and were able to increase the myelin sheath abundance and thus improve DACD. There is a strong link between REST binding and DNA methylation. Hypermethylation was observed at REST binding sites, and the recruitment of DNMT1 by REST was proposed to be a potential cause (29, 33). It has been shown that non-CpG methylation on RE1 sites specifically facilitated REST binding to cardiac targets in developing mice (65). CpA methylation has previously been reported to promote the binding of methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) to its target (66), and CpA sites are known to have a relatively greater affinity for DNMT3B than for DNMT3A (67). Similarly, our current findings suggest that hypermethylation of non-CpG sites (mainly CpA sites) in RE1 sites enhances REST binding. It is nevertheless conceivable that this discrepancy could be a result of continuous crosstalk between transcription factor binding and local DNA methylation. It will therefore be of future interest to address whether this dynamic pattern of DNA methylation differs between non-CpG and CpG cytosines in a tissue- and/or stage-specific manner and how changes in DNA methylation levels influence the functions of REST and other transcription factors during development.

CNTN1 is a GPI-anchored membrane protein with six immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains and four fibronectin type III-like domains. Heterophilic interactions between CNTN1 and its various ligands are required for key developmental events, such as neural cell adhesion, myelination, neurite growth, axonal elongation and fasciculation (68, 69). Furthermore, the binding of PTPRZ to CNTN1 expressed on the surface of OPCs inhibits their proliferation and promotes their development into mature OLs (70). CNTN1 also affects myelin formation by participating in the CNTN1-fyn-PTPα complex, which promotes the interaction of PTPα (a receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase) and fyn (a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase) (70, 71). Similarly, we found an increase in remyelination and maturation of OPCs by increasing CNTN1 expression levels in the brains of diabetic mice. Studies have identified CNTN1 as a functional ligand of Notch that induces the generation and nuclear translocation of NICD. This ligand‒receptor interaction increases oligodendrogliogenesis from progenitor cells and promotes oligodendroglial maturation (36). CNTN1 also mediates neuron–glial contacts through its association with extracellular matrix components. This ligand‒receptor interaction increases oligodendrogliogenesis from progenitor cells and promotes oligodendroglial maturation (68, 72, 73). Given the influence of CNTN1 on intercellular adhesion and glial cell interactions, we then explored the effect of CNTN1 on microglial polarization. With increasing CNTN1 protein expression, the proportion of M1 microglia decreased, and the proportion of M2 microglia increased. However, M2 macrophages are necessary for the differentiation and maturation of OLs (74). Microglia are widely regarded as the main specific phagocytes in the central nervous system. Following demyelination injury, microglia transform into an active phagocytic phenotype, migrate, and accumulate in the injured area, where they can remove myelin debris and promote myelin regeneration (75). CNTN1 expression increased microglial phagocytosis. The subsequent EM results also demonstrated a significant reduction in myelin debris. This is the first study to show that CNTN1 expression promotes microglial M2 polarization and enhances the clearance of myelin debris.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the binding of REST to target genes is affected by a variety of epigenetic mechanisms. Although we have shown that DNMT3b-mediated CpA methylation can promote the silencing effect of REST expression, its complex mechanisms require further investigation. Second, the effects of CNTN1 expression silencing on REST and DNMT3b were not verified by in vitro experiments. CNTN1 expression is essential for the connection between glial cells and axons; however, the specific mechanism and effects of CNTN1 on glia-neuron axon connections need to be elucidated. Third, diabetes itself increases the complexity of the disease. Research has demonstrated that female C57Bl/6J mice exhibit significantly greater resistance to the diabetes-inducing effects of streptozotocin (STZ) compared to their male counterparts (76). A proposed mechanism suggests that the female hormone 17 beta-estradiol (E2) confers protection on pancreatic beta-cells against STZ-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis (77). Our prior experiments have also indicated that female mice require higher doses of STZ to achieve elevated blood glucose levels, which compromises their survival duration and limits the feasibility of conducting behavioral experiments. Consequently, it is both logical and essential for us to utilize male mice in order to ensure accurate modeling of diabetes. We plan to validate and further elucidate this mechanism through in vitro experiments and other ways to build models.

Conclusion

In summary, our study highlights a paradigm of transcriptional regulation critical for diabetic remyelination that is controlled by the interaction of REST, DNMT3b and non-CpG methylation. Our findings provide new insights into the potential underlying mechanisms of Diabetes-related delays in myelination.

Experimental procedures

Reagents and antibodies

Streptozotocin (STZ) and BCA protein test kits were purchased from Solarbio. X5050 and Nanaomycin A (NA) were purchased from MedChemexpress. Recombinant Mouse Contactin one protein was purchased from Abcam. The Nissl Stain Kit and Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) Myelin Stain Kit were purchased from Solarbio. Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit, EMSA Probe Biotin Labeling Kit and Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit from Beyotime. The purchasing method of primary antibody is as follows: MBP (ab218011), CNPase (ab277621), NG2 (ab255811), NeuN (ab104224), MAP2 (ab183830), DNMT1 (ab188453), DNMT3a (ab188470), 5-methylcyto (5-mC, ab214727), Arg1 (ab233548), CD206 (ab64693), TNF-a (ab66579), iNOS (ab178945), CD68 (ab283654), IBA1 (ab283319), iNOS (ab178945) and Beta Actin (ab8226) from Abcam; CC1 (SAB4501438) purchased from MedChemexpress; Olig2 (665131-IG), DNMT3b (26971-AP), REST (22242-1-AP), and CNTN1 (13843-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech Group. Mounting Medium with DAPI (ab104139), Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 594, ab150116) and Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488, ab150077) were purchased from Abcam. Unspecified reagents were purchased from Beyotime.

Animals

Six-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology. All the experiments were conducted in accordance with European Community Guidelines on the Use of Experimental Animals, and the animals were raised in an SPF animal room of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinzhou Medical University. Relative room humidity was maintained at 40 to 50%, and the temperature was maintained at 20 to 25 °C with a 12-h light/dark photoperiod. All procedures involving animals and their care were approved (Ethics Approval Number: 240027) by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinzhou Medical University (SYXK [Liao] 2019-0007).

Experimental grouping

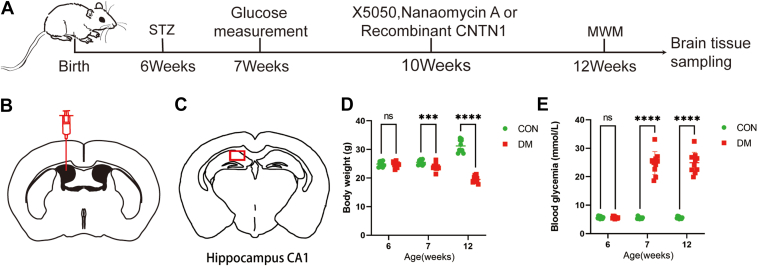

C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into six groups as follows: the CON group (control, citrate buffer, n = 20), DM group (DM, streptozotocin [STZ] dissolved in citrate buffer, n = 20), X5050 group (DM mice + X5050, n = 8), NA group (DM mice + Naumycin A, n = 10), CNTN1 group (DM mice + CNTN1 recombinant protein, n = 10), and Sham group (DM mice + sham operation, n = 10). C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with 150 mg/kg STZ (Sigma, USA) dissolved in citric acid. After 7 days of treatment, a blood glucose level ≥16.7 mmol/L was considered to indicate successful model establishment. Among CON group and DM group, 10 were subjected to behavioral experiments and sacrificed 4 weeks after the end of adaptive feeding, and another 10 were subjected to behavioral experiments and sacrificed 6 weeks later.

Stereotaxic injection

All surgeries were performed under stereotaxic guidance (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China). Mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) before undergoing craniotomy. Craniotomies were performed using a drill bit 0.5 mm in diameter over the hippocampus (1 mm posterior to bregma, ± 0.5 mm lateral to midline, 1.75 mm ventral to the dura). The mice were injected at a controlled rate of 0.5 μl/min. The micropipette was maintained in the target site for another 10 min after injection before being slowly withdrawn. Prior to performing the behavioral experiments, the mice were allowed to recover for at least 1 week after the injections (Fig. 10, A–C). Then, the mice were habituated to the behavioral environment for 1 week before starting the behavioral tests. For all drug injections, mice injected at incorrect sites were excluded from further experiments.

Figure 10.

The diabetic model was successfully constructed. A, animal experimental design. B, schematic diagram of stereotaxic injections to the lateral ventricles of mice. C, locations of pathological and immunohistochemical staining. D, changes in body weights of the mice. N = 10/group. E, changes in blood glucose levels in mice. N = 10/group. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Tissue preparation

During the experimental period, mice developed characteristic polyuria, polydipsia, and body weight loss (Fig. 10D). All mice subjected to STZ injection exhibited hyperglycemia at 1 week and 4 weeks posttreatment (Fig. 10E). All animals were transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS. For immunofluorescence staining, the mice were then transcardially perfused with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brains were postfixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight and dehydrated in 30% sucrose in PBS for 3 days. Coronal sections of 12 μm were prepared with a freezing microtome (CryoStar NX50 OP, Thermo Scientific) and then stored at −20 °C. For Western blotting, after PBS perfusion, the hippocampus in the cerebrum was dissected carefully on ice under a microscope and quickly stored at −80 °C for subsequent protein extraction.

Morris water maze (MWM)

The MWM was used to test the memory and learning abilities of the experimental mice. A tank with a diameter of 120 cm was filled with water and a platform was hidden 1 cm below the surface of the water. The water temperature was maintained between 22 and 25 °C. Mice were placed in the tank and given 1 min to find the hidden platform and another 30 s on the platform; this process was repeated 4 times daily with different starting quadrants. Mice were led to the platform if they failed to find it. EthoVision XT 15 tracking software (EthoVision XT 9.0.726, Noldus) was used to record the time spent finding the platform. The learning procedure was repeated for 5 days. On the sixth day of the experiment, the platform was removed, and the mice underwent a probe trial in which they swam freely in the tank for 1 min. The percentage of time spent in the target quadrant was recorded by EthoVision XT 15 tracking software.

Luxol-fast-blue staining

LFB staining was performed to detect demyelinated lesions. Briefly, after being washed in PBS, brain slices were incubated in prewarmed 0.1% LFB staining buffer at 60 °C for 6 to 8 h and were then cooled and differentiated in Li2CO3 for 2 min. When differential staining was complete, the slices were successively dehydrated in 75%, 95% and 100% alcohol and air-dried. Then, the slices were mounted using neutral gum (Baso). Photos were taken with an optical microscope (BX51, Olympus).

Nissl staining

The brain sections were dehydrated in 95% and 70% ethanol for 2 min each and were then washed in distilled water for 2 min. The sections were stained with 0.5% cresyl violet (Sigma‒Aldrich) for 2 min and washed in distilled water for 10 s, followed by dehydration in 100% ethanol and twice in xylene for 2 min. Then, the slices were mounted using neutral gum (Baso). Photos were taken with an optical microscope (BX51, Olympus).

Immunohistochemistry

The slices were washed in PBS and then permeabilized with 0.25% Triton-X100 (Solarbio Life Sciences) for 15 min at room temperature. After permeabilization, the brain slices were blocked in a blocking buffer (QuickBlock Blocking Buffer for Immunol Staining, Beyotime) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies. The sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor–labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were obtained by fluorescence microscopy (BX51, Olympus).

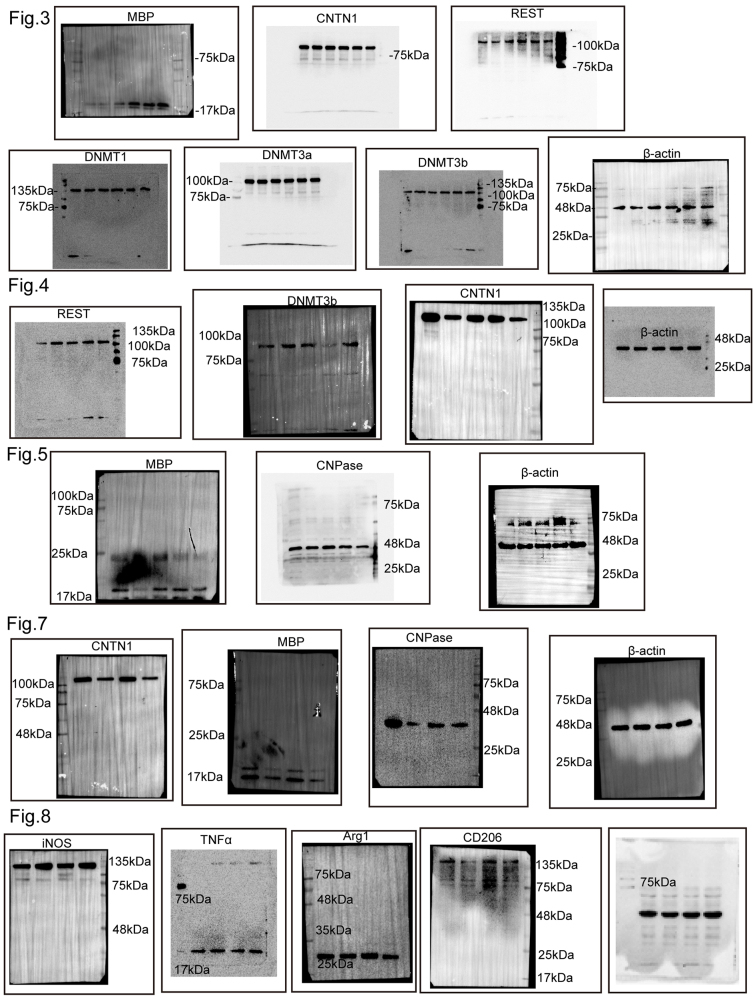

Western blot

Protein from the lesion areas was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) containing PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail, and phosphatase inhibitor (all from Servicebio). A BCA kit (Beyotime) was used to determine the protein concentration. Total protein (20 μg) was separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‒PAGE) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Boster Biological Technology). The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies. After incubation for 16 to 18 h at 4 °C, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the membranes were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence kits (Advansta) and a Gelview 6000 Pro system (BLT, China). The integrated optical density (OD) data were collected and analyzed with ImageJ (NIH, USA). The protein expression was normalized to that of the internal control β-actin. The original image of the blot is added to the supplement (Fig. S2).

DNA methylation assay

Overall DNA methylation in cells was analyzed using a methylated DNA quantification kit (ab117128, Abcam), which quantifies global DNA methylation by specifically measuring the levels of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) in a microplate-based format. Genomic DNA was added to microplates and bound to assay wells. Then, the capture antibody, detection antibody, enhancer solution and developing solution were added after washing the wells. The fluorescence intensity was measured at an optimal optical density (OD) of 450 nm using a plate reader (Cytation 5). A simple calculation of the percentage of 5-mC of the total DNA in was performed using the following formula: .

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

An EMSA kit (Beyotime, GS009) was used to detect REST binding to CNTN1-RE1 using a nuclear extract kit (Beyotime, P0027) on tissue taken from the hippocampus. The complementary oligonucleotides of differentially methylated CNTN1-RE1 (Fig. 7A) were annealed in a 50 μl reaction volume having equimolar concentrations of each oligo in 1× TNE buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Further, the oligos were denatured at 95 °C in a water bath for 15 min and allowed to cool down gradually. It was incubated at room temperature overnight and stored the annealed oligos at −20 °C for further use in EMSA experiments. CNTN1-RE1 oligonucleotides with methylated nonCpG or CpG sites were labelled with biotin at their 3-ends (Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit, Beyotime, GS008).

In the supershift experiments, the nuclear extracts were preincubated with an anti-REST antibody. Protein–DNA binding complexes were separated on a 4% DNA retardation gel, detected using an ECL reagent and quantified using ImageJ software.

Electron microscopy (EM)

Mice were anaesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium and perfused briefly with PBS followed by 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate, pH 7.2. The hippocampus was removed, and the tissue was fixed in fresh fixative overnight at 4 °C. Tissues were rinsed in PBS, postfixed in 1% OsO4 in PBS for 1 h, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, infiltrated with propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon. Semithin sections were stained using toluidine blue, and thin sections were stained using lead citrate.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9. For statistical analysis, the Shapiro–Wilk test was first used to determine whether the data were normally distributed, followed using two-tailed Student’s t tests for comparisons between two groups and one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s or Bonferroni post hoc correction were applied for multiple comparisons. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Data availability

All the data required for this manuscript are available either in the main article or in the supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

W. Q. L. and X. Z. L. supervision; T. F. Y. writing–original draft; T. F. Y. and L. S. data curation; Z. Y. W. writing–review & editing; Z. Y. W., S. X. Y., and H.-D. Y. methodology; Z. Z. conceptualization; L. S. visualization; L. N. and D. S. project administration; Y. H. S., J. Q. L., and W. Z. L. formal analysis; Z. Z. Y. software.

Funding and additional information

This study was supported by the Foundation of Education Department of Liaoning Province. No: LJKMZ20221241; Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province of China. No: 2023-MS-312.1; National Natural Science Foundation of China. No: 81571383; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. No: 2017M612870.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Patrick Sung

Contributor Information

Xue-Zheng Liu, Email: Liuxuezheng@jzmu.edu.cn.

Zhong-Fu Zuo, Email: zuozhongfu@jzmu.edu.cn.

Supporting information

Figure S1.

Figure S2.

References

- 1.Saeedi P., Petersohn I., Salpea P., Malanda B., Karuranga S., Unwin N., et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019;157 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunblatt E., Bartl J., Riederer P. The link between iron, metabolic syndrome, and Alzheimer's disease. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2011;118:371–379. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biessels G.J., Staekenborg S., Brunner E., Brayne C., Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong R.H., Scholey A., Howe P.R. Assessing premorbid cognitive ability in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus--a review with implications for future intervention studies. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2014;14:547. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0547-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellia C., Lombardo M., Meloni M., Della-Morte D., Bellia A., Lauro D. Diabetes and cognitive decline. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2022;108:37–71. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulton C.D., Stewart R., Amiel S.A., Laake J.P., Ismail K. Factors associated with cognitive impairment in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Aging Ment. Health. 2016;20:840–847. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1040723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinclair A.J., Girling A.J., Bayer A.J. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. All Wales Research into Elderly (AWARE) Study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2000;50:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konopaske G.T., Dorph-Petersen K.A., Sweet R.A., Pierri J.N., Zhang W., Sampson A.R., et al. Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomassy G.S., Berger D.R., Chen H.H., Kasthuri N., Hayworth K.J., Vercelli A., et al. Distinct profiles of myelin distribution along single axons of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. Science. 2014;344:319–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1249766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziehn M.O., Avedisian A.A., Tiwari-Woodruff S., Voskuhl R.R. Hippocampal CA1 atrophy and synaptic loss during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, EAE. Lab. Invest. 2010;90:774–786. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich W.D., Alonso O., Busto R. Moderate hyperglycemia worsens acute blood-brain barrier injury after forebrain ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1993;24:111–116. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaskiewicz E. Epitopes on myelin proteins recognized by autoantibodies present in multiple sclerosis patientsPostepy Hig. Med. Dosw. (Online) 2004;58:472–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding C., He Q., Li P.A. Diabetes increases expression of ICAM after a brief period of cerebral ischemia. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;161:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan P.H., Schmidley J.W., Fishman R.A., Longar S.M. Brain injury, edema, and vascular permeability changes induced by oxygen-derived free radicals. Neurology. 1984;34:315–320. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehncrona S., Hauge H.N., Siesjo B.K. Enhancement of iron-catalyzed free radical formation by acidosis in brain homogenates: differences in effect by lactic acid and CO2. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:65–70. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bralet J., Schreiber L., Bouvier C. Effect of acidosis and anoxia on iron delocalization from brain homogenates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43:979–983. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90602-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucchinetti C.F., Popescu B.F., Bunyan R.F., Moll N.M., Roemer S.F., Lassmann H., et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2188–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferenczy M.W., Marshall L.J., Nelson C.D., Atwood W.J., Nath A., Khalili K., et al. Molecular biology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:471–506. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05031-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlmann T., Miron V., Cui Q., Wegner C., Antel J., Brück W. Differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2008;131:1749–1758. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arthur-Farraj P., Moyon S. DNA methylation in Schwann cells and in oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2020;68:1568–1583. doi: 10.1002/glia.23784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koreman E., Sun X., Lu Q.R. Chromatin remodeling and epigenetic regulation of oligodendrocyte myelination and myelin repair. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2018;87:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fatemi M., Hermann A., Gowher H., Jeltsch A. Dnmt3a and Dnmt1 functionally cooperate during de novo methylation of DNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4981–4984. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z., Tang B., He Y., Jin P. DNA methylation dynamics in neurogenesis. Epigenomics. 2016;8:401–414. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore L.D., Le T., Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z.F., Paquette A.J., Anderson D.J. NRSF/REST is required in vivo for repression of multiple neuronal target genes during embryogenesis. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:136–142. doi: 10.1038/2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majumder S. REST in good times and bad: roles in tumor suppressor and oncogenic activities. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1929–1935. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuccato C., Belyaev N., Conforti P., Ooi L., Tartari M., Papadimou E., et al. Widespread disruption of repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencer factor occupancy at its target genes in Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6972–6983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4278-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canzonetta C., Mulligan C., Deutsch S., Ruf S., O'Doherty A., Lyle R., et al. DYRK1A-dosage imbalance perturbs NRSF/REST levels, deregulating pluripotency and embryonic stem cell fate in down syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:388–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballas N., Grunseich C., Lu D.D., Speh J.C., Mandel G. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewald L.E., Rodriguez J.P., Levine J.M. The RE1 binding protein REST regulates oligodendrocyte differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:3470–3483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2768-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrajano J.J., Qureshi I.A., Gokhan S., Zheng D., Bergman A., Mehler M.F. Differential deployment of REST and CoREST promotes glial subtype specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Covey M.V., Streb J.W., Spektor R., Ballas N. REST regulates the pool size of the different neural lineages by restricting the generation of neurons and oligodendrocytes from neural stem/progenitor cells. Development. 2012;139:2878–2890. doi: 10.1242/dev.074765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballas N., Mandel G. The many faces of REST oversee epigenetic programming of neuronal genes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stadler M.B., Murr R., Burger L., Ivanek R., Lienert F., Schöler A., et al. DNA-binding factors shape the mouse methylome at distal regulatory regions. Nature. 2011;480:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature10716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu Q.D., Ang B.T., Karsak M., Hu W.P., Cui X.Y., Duka T., et al. F3/contactin acts as a functional ligand for Notch during oligodendrocyte maturation. Cell. 2003;115:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Q.D., Ma Q.H., Gennarini G., Xiao Z.C. Cross-talk between F3/contactin and Notch at axoglial interface: a role in oligodendrocyte development. Dev. Neurosci. 2006;28:25–33. doi: 10.1159/000090750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui X.Y., Hu Q.D., Tekaya M., Shimoda Y., Ang B.T., Nie D.Y., et al. NB-3/Notch1 pathway via Deltex1 promotes neural progenitor cell differentiation into oligodendrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25858–25865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faivre-Sarrailh C., Devaux J.J. Neuro-glial interactions at the nodes of Ranvier: implication in health and diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:196. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranscht B. Sequence of contactin, a 130-kD glycoprotein concentrated in areas of interneuronal contact, defines a new member of the immunoglobulin supergene family in the nervous system. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1561–1573. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massaro A., Bizzoca A., Corsi P., Pinto M.F., Carratù M.R., Gennarini G. Significance of F3/Contactin gene expression in cerebral cortex and nigrostriatal development. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2012;50:221–237. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch T., Brugger T., Bach A., Gennarini G., Trotter J. Expression of the immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecule F3 by oligodendrocyte-lineage cells. Glia. 1997;19:199–212. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199703)19:3<199::aid-glia3>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puzzo D., Bizzoca A., Privitera L., Furnari D., Giunta S., Girolamo F., et al. F3/Contactin promotes hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory in adult mice. Hippocampus. 2013;23:1367–1382. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimazaki K., Hosoya H., Takeda Y., Kobayashi S., Watanabe K. Age-related decline of F3/contactin in rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;245:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imayoshi I., Shimojo H., Sakamoto M., Ohtsuka T., Kageyama R. Genetic visualization of notch signaling in mammalian neurogenesis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:2045–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiberi L., Van Den Ameele J., Dimidschstein J., Piccirilli J., Gall D., Herpoel A., et al. BCL6 controls neurogenesis through Sirt1-dependent epigenetic repression of selective Notch targets. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/nn.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor M.K., Yeager K., Morrison S.J. Physiological Notch signaling promotes gliogenesis in the developing peripheral and central nervous systems. Development. 2007;134:2435–2447. doi: 10.1242/dev.005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bischof M., Weider M., Kuspert M., Nave K.A., Wegner M. Brg1-dependent chromatin remodelling is not essentially required during oligodendroglial differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:21–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1468-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He D., Marie C., Zhao C., Kim B., Wang J., Deng Y., et al. Chd7 cooperates with Sox10 and regulates the onset of CNS myelination and remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nn.4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J., Magri L., Zhang F., Marsh N.O., Albrecht S., Huynh J.L., et al. Chromatin landscape defined by repressive histone methylation during oligodendrocyte differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:352–365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2606-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen S., Sandoval J., Swiss V.A., Li J., Dupree J., Franklin R.J.M., et al. Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:1024–1034. doi: 10.1038/nn.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu Y., Chen Y., Kim B., Wang H., Zhao C., He X., et al. Olig2 targets chromatin remodelers to enhancers to initiate oligodendrocyte differentiation. Cell. 2013;152:248–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan G., Beard C., Chen R.Z., Csankovszki G., Sun Y., Siniaia M., et al. DNA hypomethylation perturbs the function and survival of CNS neurons in postnatal animals. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:788–797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00788.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hutnick L.K., Golshani P., Namihira M., Xue Z., Matynia A., Yang X.W., et al. DNA hypomethylation restricted to the murine forebrain induces cortical degeneration and impairs postnatal neuronal maturation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:2875–2888. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fan G., Martinowich K., Chin M.H., He F., Fouse S.D., Hutnick L., et al. DNA methylation controls the timing of astrogliogenesis through regulation of JAK-STAT signaling. Development. 2005;132:3345–3356. doi: 10.1242/dev.01912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Z., Huang K., Yu J., Le T., Namihira M., Liu Y., et al. Dnmt3a regulates both proliferation and differentiation of mouse neural stem cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2012;90:1883–1891. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li E., Bestor T.H., Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unterberger A., Andrews S.D., Weaver I.C., Szyf M. DNA methyltransferase 1 knockdown activates a replication stress checkpoint. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:7575–7586. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takizawa T., Nakashima K., Namihira M., Ochiai W., Uemura A., Yanagisawa M., et al. DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iurlaro M., Von Meyenn F., Reik W. DNA methylation homeostasis in human and mouse development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017;43:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith Z.D., Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gopalakrishnan S., Van Emburgh B.O., Robertson K.D. DNA methylation in development and human disease. Mutat. Res. 2008;647:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu H., Liu X., Deng Y., Qing H. DNA methylation, a hand behind neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moyon S., Huynh J.L., Dutta D., Zhang F., Ma D., Yoo S., et al. Functional characterization of DNA methylation in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell Rep. 2016;15:748–760. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moyon S., Ma D., Huynh J.L., Coutts D.J.C., Zhao C., Casaccia P., et al. Efficient remyelination requires DNA methylation. eNeuro. 2017;4:168–180. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0336-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang D., Wu B., Wang P., Wang Y., Lu P., Nechiporuk T., et al. Non-CpG methylation by DNMT3B facilitates REST binding and gene silencing in developing mouse hearts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3102–3115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gabel H.W., Kinde B., Stroud H., Gilbert C.S., Harmin D.A., Kastan N.R., et al. Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature. 2015;522:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature14319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aoki A., Suetake I., Miyagawa J., Fujio T., Chijiwa T., Sasaki H., et al. Enzymatic properties of de novo-type mouse DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3506–3512. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Falk J., Bonnon C., Girault J.A., Faivre-Sarrailh C. F3/contactin, a neuronal cell adhesion molecule implicated in axogenesis and myelination. Biol. Cell. 2002;94:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karagogeos D. Neural GPI-anchored cell adhesion molecules. Front. Biosci. 2003;8:s1304–s1320. doi: 10.2741/1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lamprianou S., Chatzopoulou E., Thomas J.L., Bouyain S., Harroch S. A complex between contactin-1 and the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPRZ controls the development of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:17498–17503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108774108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng L., D'alessandri L., Kalousek M.B., et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha (PTPalpha) and contactin form a novel neuronal receptor complex linked to the intracellular tyrosine kinase fyn. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:707–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Colakoglu G., Bergstrom-Tyrberg U., Berglund E.O., Ranscht B. Contactin-1 regulates myelination and nodal/paranodal domain organization in the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E394–E403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313769110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haenisch C., Diekmann H., Klinger M., Gennarini G., Kuwada J.Y., Stuermer C.A.O. The neuronal growth and regeneration associated Cntn1 (F3/F11/Contactin) gene is duplicated in fish: expression during development and retinal axon regeneration. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miron V.E., Boyd A., Zhao J.W., Yuen T.J., Ruckh J.M., Shadrach J.L., et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sierra A., Abiega O., Shahraz A., Neumann H. Janus-faced microglia: beneficial and detrimental consequences of microglial phagocytosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;7:6. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saadane A., Lessieur E.M., Du Y., Liu H., Kern T.S. Successful induction of diabetes in mice demonstrates no gender difference in development of early diabetic retinopathy. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Le May C., Chu K., Hu M., Ortega C.S., Simpson E.R., Korach K.S., et al. Estrogens protect pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:9232–9237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data required for this manuscript are available either in the main article or in the supporting information.