Abstract

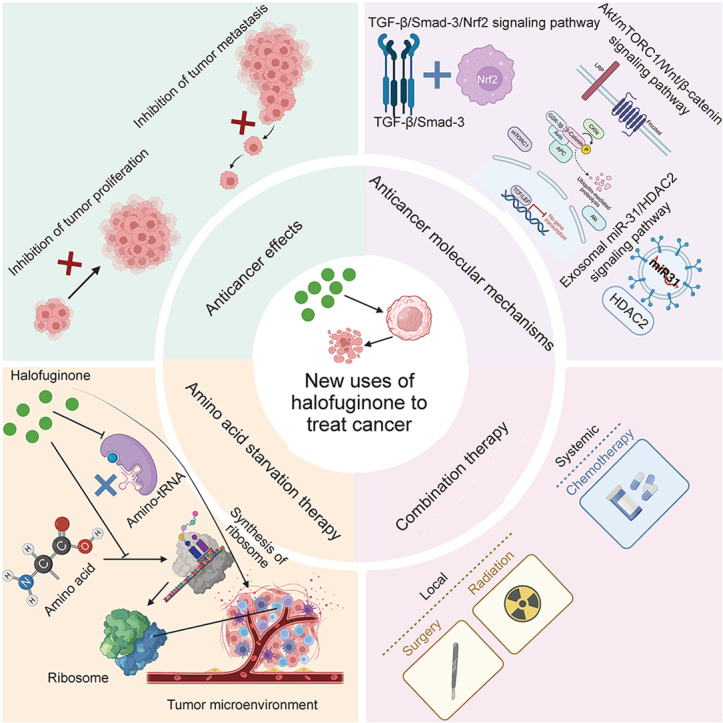

The small-molecule alkaloid halofuginone (HF) is obtained from febrifugine. Recent studies on HF have aroused widespread attention owing to its universal range of noteworthy biological activities and therapeutic functions, which range from parasite infections and fibrosis to autoimmune diseases. In particular, HF is believed to play an excellent anticancer role by suppressing the proliferation, adhesion, metastasis, and invasion of cancers. This review supports the goal of demonstrating various anticancer effects and molecular mechanisms of HF. In the studies covered in this review, the anticancer molecular mechanisms of HF mainly included transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/Smad-3/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), serine/threonine kinase proteins (Akt)/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1(mTORC1)/wingless/integrated (Wnt)/β-catenin, the exosomal microRNA-31 (miR-31)/histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) signaling pathway, and the interaction of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and immune cells. Notably, HF, as a novel type of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent inhibitor that is often combined with prolyl transfer RNA synthetase (ProRS) and amino acid starvation therapy (AAS) to suppress the formation of ribosome, further exerts a significant effect on the tumor microenvironment (TME). Additionally, the combination of HF with other drugs or therapies obtained universal attention. Our results showed that HF has significant potential for clinical cancer treatment.

Keywords: Halofuginone, TGF-β, MicroRNA, Exosome, Tumor microenvironment, ECM

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The anticancer molecular mechanisms of HF mainly included TGF-β/Smad3/Nrf2, Akt/mTORC1/Wnt/β-catenin, the exosomal miR-31/HDAC2 signaling pathway, and the interaction of the extracellular matrix and immune cells.

-

•

HF treatment can significantly disrupt the collagen network in tumors via modulating the immunosuppressive TME, including enrichment of tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells and promoting infiltration of Tregs.

-

•

HF, as a novel type of ATP-dependent inhibitor that is often combined with ProRS and AAS to suppress the formation of ribosome, further exerts a significant effect on the TME.

1. Introduction

Halofuginone (HF) is obtained from febrifugine, which comes from Dichroa febrifuga. HF has been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to treat malarial fevers for more than 2,000 years [[1], [2], [3]]. Notably, in the early 1980s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) certified the use of HF [4], and since then, it has approved HF to treat several diseases, including coccidia in 1971, cryptosporidiosis in 1999, scleroderma in 2001, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in 2012. HF has therapeutic value and is known for its antifibrosis and antiparasite effects as well as for its anti-autoimmunity disease and anticancer effects [[5], [6], [7], [8]].

The cancer incidence and mortality rate in China both rank first in the world, according to the World Cancer Statistics Report in 2020 [9]. However, traditional anticancer drugs such as paclitaxel (PTX) and adriamycin (ADM) have been found in clinical trials to promote the lung metastasis of breast cancer, raising extensive concerns about its efficacy [10,11]. The discovery and development process of new drugs takes at least 5–8 years while costing more. Therefore, repurposing existing drugs has been proposed to deal with the conundrum. Notably, HF has potential anticancer activity compared with clinically used anticancer drugs. Our early test results showed that HF had an inhibitory effect on (MDA-MB-231) cells (a type of triple-negative breast cancer cells), which was somewhat better than that of ADM and PTX [12]. Therefore, we selected HF to carry out a further investigation.

HF can hinder development and progression of tumors in several animal models, including chemically induced metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma and bladder carcinoma [13,14], glioma [15], mammary tumors in polyoma middle T antigen transgenic mice [16], fibrous histiocytoma brain metastasis [17], prostate cancer, xenografts of von Hippel-Lindau pheochromocytoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and Wilms’ tumor [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. HF also can constrain cancer growth, invasion, metastasis, adhesion, and angiogenesis. When combined with other drugs to treat cancer that follow different modalities, HF has enabled a decrease in the requried dosage of chemotherapeutic drugs, thus alleviating some of the burden of treatment on patients with cancer [23].

In this review, our main goal is to summarize and analyze the anticancer effects and molecular mechanisms of HF. Notably, more pivotal molecules and influential elements such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), the Smad family, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), exosomes, microRNA (miRNA), extracellular matrix (ECM), multiple immune cells, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) have been found to participate in the occurrence and development of cancers. Mechanistically, HF inhibited the TGF-β/Smad3 signal pathway involved in metastatic tumors. Notably, exosomes are often involved in the development of tumor metastasis. In addition, by inhibiting the production of exosomes, exosomal microRNA 31 (miR-31) was reduced, targeting histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and regulating cell-cycle regulatory protein levels, which enhanced the HF's anticancer ability. More improtantly, TME refers to the close relationship between tumor metastasis and the internal-external environments in which tumor cells reside. HF is a novel inhibitor that is dependent on adenosine triphosphate (ATP). By combining it with prolyl transfer RNA synthetase (ProRS), it suppressed ribosome formation and exerted a TME effect. HF also can triggered a cellular amino acid starvation response, further limiting protein synthesis and quickly reducing Nrf2 [24]. Because its primary mode of action is distinct, it is unlike conventional chemotherapies. Thus, HF appears to be suitable for use in combination therapy, which has been validated to treat cancer xenografts. This review offers a comprehensive overview of recent progress in research on HF, including new methods to repurpose it for cancer therapy.

2. Anticancer effect and molecular mechanism of HF

2.1. Anticancer and antimetastatic effect

Previous studies have shown that HF applied as a traditional anti-parasite drug has a role in combating fibrosis, autoimmune disease, and cancers. Of note, increasing evidence indicates that HF possesses an excellent antitumor effect. Simultaneously, the combination therapy of HF with other drugs has been employed to investigate the inhibition of tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Notably, 50 research reports have been released on the antitumor effect of HF in the past decade. Taken together, the inhibition of critical signaling pathways and related molecular mechanism for numerous cancers is summarized and analyzed in (Table 1) [13,[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]]. As reported, HF, as a broad-spectrum antitumor drug, has mainly shown superior activity against four types of cancers: lung [56], pancreatic [57], colorectal [58,59], and breast cancer [[60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66]]. HF has also been utilized to address some troublesome tumors, such as esophageal squamous carcinoma, uterine leiomyoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, melanoma, and leiomyoma.

Table 1.

Molecular mechanisms of halofuginone (HF) induced the inhibition of various cancers.

| Molecular mechanisms | Types of cancer | Signal pathways | Crucial molecules | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β and ROS | Lung | TGF-β/BMP | BMP | [13] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Lung | TGF-β/Smad4, 7 | Smad4 | [25] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Lung | TGF-β/EMT | Vimentin | [26,27] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Lung | TGF-β | TGF-β | [28] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Osteosarcoma | TGF-β/Smad3 | Smad3 | [29,30] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Melanoma | TGF-β/Smad3, 7 | CTGF and CXCR4 | [31] |

| TGF-β and ROS | All | TGF-β/Nrf2 | Nrf2 | [32] |

| TGF-β and ROS | All | TGF-β/Smad3 | TGF-β | [32] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Pancreatic | Nrf2-ALDH3A1 | ALDH3A1 | [33] |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | Colorectal | Akt/mTORC1 | Akt and mTORC1 | [34] |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | All | LKB1 and AMPK | AMPK, Akt, and mTORC1 | [[35], [36], [37], [38]] |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | All | Akt/mTORC1 | STMN1 and p53 | [39] |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | Breast | STMN1 and p53 | Wnt and β-catenin | [40,41] |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | Breast | Wnt and β-catenin | Lnc-RNAs | [41] |

| Exosomes | All | Lnc-RNAs/ROR | miRNAs | [[42], [43], [44], [45]] |

| Exosomes | All | miRNAs | miR-31 | [[46], [47], [48], [49]] |

| TGF-β and ROS | Breast | miR-31 and HDAC2 | TGF-β | [50] |

| Exosomes | Pancreatic | TGF-β/Smad3 | Akt/mTOR | [51] |

| Other mechanisms | ESCC | Akt/mTOR | ER-α and PR | [52] |

| Other mechanisms | UTLM | ER-α and PR | PLTP | [53,54] |

| Other mechanisms | Leiomyoma | MAPK and SRC | MAPK | [55] |

TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ROS: reactive oxidative stress; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; CXCR4: chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; ALDH3A1: aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member A1; Akt: serine/threonine kinase proteins; mTORC1: mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; LKB1: liver kinase B1; AMPK: adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; STMN1: recombinant Stathmin 1; Wnt: wingless/integrated; Lnc-RNAs: long-noncoding RNAs; ROR: receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1; miRNAs: microRNAs; HDAC2: histone deacetylase 2; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; ESCC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ER-α: estrogen receptor-α; PR: progesterone receptor; UTLM: uterine leiomyoma; PLTP: plasma phospholipid transfer protein; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; SRC: sarcoma.

Increasing evidence indicates that the inhibition of the migration, invasion, and metastasis of cancer is the key scientific issue in the research on cancers such as breast cancer, especially in the later stages. More than 90% of cancer-related mortality is attributed to metastases, which occur when tumor cells colonize from a primary location to a secondary organ site [[67], [68], [69]]. In this multistep process, cancer cells are disengaged from the primary tumor and cross into a surrounding microenvironment. After they intravasate and survive hemodynamic circulation, they extravasate to secondary organs. The primary metastatic organs affected by breast cancer include the bone [70], liver [71], lung [[72], [73], [74]], and brain [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. The incidence of lung metastasis and brain metastasis has been relatively higher than that of other organ metastases, both in clinical cases and experimental animal models [79]. To assess the impact of HF on tumor growth, the TME, and metastasic development, we used a preclinical osteosarcoma model. We conducted in vivo experiments, which indicated that HF limited the growth of the primary tumor and the development of lung metastases.

Juárez et al. [67] showed that HF could effectively treat bone metastases by obstructing TGF-β and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling. HF also blocked TGF-β signaling in prostate cancer cell line (PC3) and Michigan Cancer Foundation-breast cancer-231 (MDA-MB-231) cells, which hindered the expression of TGF-β-regulated metastatic genes, phosphorylation of Smad-proteins, and TGF-β-induced Smad-reporter. Collectively, HF reduced prostate and breast cancer bone metastases in mice. When combined with FDA-approved treatment, HF effectively treated breast and prostate cancer complications. Reportedly, HF extract slowed the growth of breast cancer cells and generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis, which are possible anticancer agents [80]. After 12-O-tetraecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) stimulation, HF also stopped the invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231 and Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) human breast cancer cells. HF blocked the angiogenesis formation of essential vasculature for the development of solid tumors and worked as a superhighway for metastases. In several systems that experimented with sequential events in the angiogenic cascade, HF-dependent inhibition of ECM synthesis had a profound inhibitory effect on the formation of capillary tubes, basement membrane invasion, deposition of subendothelial ECM, and vascular sprouting.

2.2. TGF-β signaling pathway inhibition

2.2.1. TGF-β-induced signaling pathway inhibition

HF is a powerful molecule obtained from plants, which reportedly can treat lung cancer. In this review, we verified the molecular anticancer mechanisms of HF in cancer cells derived from the lung [25]. We found that TGF-β was an important molecular target in cancers as well as in several other diseases. Concomitantly, the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) was found to be an extremely significant process in the occurrence and development of cancers. Some research results showed that HF inhibited radiation-induced EMT and that suppression of TGF-β1 signaling might be responsible for this effect [26,27]. Moreover, the combination of HF with radiotherapy was utilized to restrain TGF-β1 signaling to further inhibit the growth of lung cancer [28]. These studies preliminarily explored the possible mechanisms associated with these effects (Fig. 1).

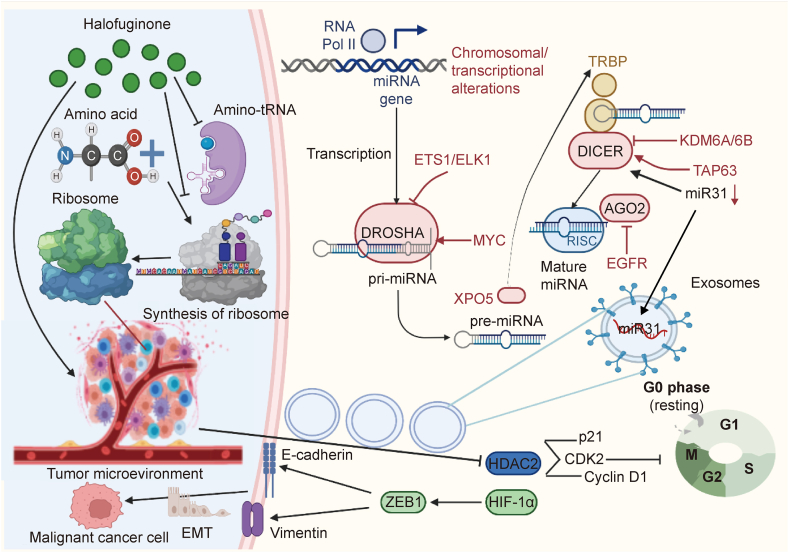

Fig. 1.

Halofuginone (HF) inhibited the Smad3 phosphorylation which was the downstream of the transforming growth factor-β ((TGF-β)) signaling pathway, impeding the transition of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and fibrosisalso via F-actin augmentation and nuclear factor erythroid derived 2-like 2 (Nrf2) accumulation. MH1: medicago sativa helicase; KEAP1: kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; ALDH3A1: aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member A1; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

The primary malignant bone tumor found in children and adolescents is osteosarcoma. When metastases are present at diagnosis, prognosis is poor [81,82] with a 50%–70% survival rate for types of occurrences and development at five years [29]. Prognosis has not improved in recent decades, and similar research has shown that TGF-β/Smad cascade may be crucial in the progression of osteosarcoma metastates. According to recent studies, HF has been shown to inhibit the TGF-β/Smad3 cascade and osteosarcoma progression [30]. By inducing tumor secretion of pro-metastatic factors that act on bone cells to alter the skeletal microenvironment, bone-derived TGF-β fueled melanoma bone metastasis. HF, a plant alkaloid derivative, blocks TGF-β signaling and has antiproliferative and antiangiogenic properties. Juárez et al. [31] also showed that HF therapy slowed the development and progression of bone metastases caused by melanoma cells by inhibiting TGF-β signaling. HF also blocked the TGF-β/Smad3 cascade and other TGF-β targets that are involved in metastatic dissemination, including matrix-metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2). These results indicated that HF targeted the tumor cells and the TME, thus limiting primary osteosarcoma development and associated lung metastasis. HF may be a suitable therapeutic agent to fight osteosarcoma tumor progression, most notably, against dissemination of lung metastises.

2.2.2. Inhibition of TGF-β combined with other factors' signaling pathways

A viable target for pharmacological intervention is the transition from fibroblast to myofibroblast in cancer, fibrosis, and wound healing. Myofibroblasts share properties, such as TGF-β signaling, have different origins and localization. HF is an inhibitor of Smad3 phosphorylation, which is downstream of the TGF-β signaling pathway. As a result, regardless of origin or location, it can limit the fibroblast activation and synthesis of ECM. Related research has indicated that HF can target TGF-β signaling and inhibit activation of fibroblast, making it suitable to treat fibrosis and cancer [32]. HF is a translation inhibitor, and Nrf2 has a short half-life that is sensitive to HF treatment [24]. Results of prior research demonstrated that applying less-toxic HF in a low dose quickly reduced levels of Nrf2 protein. HF can also limit Nrf2-related cancer cell resistance to treatment. Preclinical evidence has suggested that because HF is an Nrf2 inhibitor, it can treat cancers that are resistant to readiation and chemotherapy . As the central regulator of the oxidative stress response, Nrf2 holds significant potential as a therapy to treat a variety of cancers. The clinical applications of novel Nrf2 inhibitors have been studied in Nrf2-activated cancers. Furthermore, administration of HF also reduced the number of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias in p53 mutant (KPC) and pancreas-specific Kras mice [33]. A mechanistic study of mouse pancreatic cancer cells showed that HF downregulated aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 (ALDH3A1) (Fig. 1). Nrf2 induced diethyl maleate, which upregulated ALDH3A1, and ALDH3A1 knockdown caused the Nrf2-activated cancer cells to be sensitized to gemcitabine. As a result, ALDH3A1 may contribute to gemcitabine resistance because it is regulated by Nrf2. Thus, we verified that HF has therapeutic benefits for pancreatic cancers activated by Nrf2. Furthermore, a novel Nrf2 inhibitor HF in related research revealed a synergistic effect with gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer [33,83].

2.3. Autophagy-related mechanism

Some promising mechanisms, including the autophagy signaling pathway, have been found to be related to the effect of HF on colorectal cancer (CRC). Autophagy plays a primary role in metabolism and tumorigenesis. One study found that HF downregulated serine/threonine kinase proteins (Akt)/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway and demonstrated anticancer activity against CRC [34]. The Akt/mTORC1 pathway activated the Warburg effect in cancer. HF treatment inhibited CRC growth both in vivo and in vitro by regulating the Akt/mTORC1 signaling pathway (Fig. 2). In nude mice inoculated with HCT116 cells, HF retarded tumor growth and demonstrated anticancer activity by regulating the metabolic activity of Akt/mTORC1 in CRC. Other investigations indicated that HF slowed EMT and proliferation of breast cancer through the wingless/integrated (Wnt)/β-catenin signal pathway. Notably, proliferation, EMT, angiogenesis, and metastasis were related to the Akt/mTORC1 and Wnt/β-catenin signal pathways, which further indicates cross-talk between the two signaling pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Halofuginone (HF) activates serine/threonine protein kinase Unc-51 like kinase 1 (ULK1) by inducing downregulation of its phosphorylation site. By combining serine/threonine kinase proteins (Akt)/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) with the wingless/integrated (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling pathway, autophagic flux is induced under conditions that are rich in nutrients. LRP: leucine-responsive regulatory protein; APC: antigen-presenting cell; CK1α: casein kinase 1 alpha; GSK-3β: glycogen synthase kinase-3β; 4EBP1: recombinant human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; HK-II: human kidney-2; NADP: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen; ROS: reactive oxidative stress; GPI: glucose phosphate isomerase; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; PGAL: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; TCF: transcription factor; LEF: lymphoid enhancer factor; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

HF can limit CRC growth. How HF can regulate autophagy and metabolism to limit cancer growth is unclear. The autophagy role in cancer depends on the type of tumor as well as its stage and genetic context. Currently, it is widely believed that autophagy is a double-edged sword in cancer: it not only blocks tumor initiation, but also can enhance tumorigenesis because it helps cancer cells survive under duress [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. Chen et al. [70] determined that HF was able to activate serine/threonine protein kinase Unc-51 like kinase 1 (ULK1) because it downregulated the phosphorylation site on Ser757 by the Akt/mTORC1 signaling pathway. As a result, autophagic flux was inducted under conditions that were rich in nutrients. More interestingly, they found that HF inhibited glycolysis under autophagy in vivo. HF thus has been shown to play a dual role in autophagic modulation according to the anti-CRC nutritional conditions. Xia et al. [3] investigated the effect of HF on azoxymethane-induced CRC in a rat model. In summary, HF may warrant evaluation as a supportive drug in the treatment of CRC in the future. To investigate how breast cancer cells migrate and invade, HF-induced autophagy was used [40,41] to shed new light on the prevention and treatment of breast cancer.

2.4. Exosome-related mechanism

Double-layered extracellular vesicles (30–150 nm in diameter) called exosomes are secreted by diverse types of cells, most notably, tumor cells [[84], [85], [86], [87]]. Tumor cell-derived exosomes (TEXs) have immunomodulatory proteins, including, for example, heat shock proteins (HSPs), tumor antigens, TGF-β, and major histocompatibility complex class I and II (MHC I and MHC II). All these proteins are responsible for immune stimulation and suppression at the dendritic cell level [[88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95]]. These extracellular messengers between the TMC and tumor cells exchange information about their numerous components, such as long-noncoding RNAs (Lnc-RNAs) [[42], [43], [44], [45],96,97]. Exosomes are made up of miscellaneous membranous and soluble lipids as well as proteins and RNAs, such as miRNAs. These molecules transmit their molecular content from cell to cell and thus are essential in intercellular indirect and direct communication [[46], [47], [48], [49]]. Because exosomes move biologically active miRNAs between the TME and tumor cells, they have an important impact on the development of tumors. Exosomal miRNAs derived from tumors cause TME matrix reprogramming and create a microenvironment that supports tumor growth, immune escape, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance. The proteins (e.g., suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA)) are targeted by the exosomal miRNAs (e.g., miR-222-3p, miR-21, and miR-10a) and the molecules (p-STAT3, p-p65, p-AKT, and p53) are activated [98]. The immune microenvironment is reshaped by these exosomal miRNAs, which mediate immunosuppression. Patients with tumors have markedly higher levels of serum exosomes than healthy controls. The initiation, progression, and invasion of tumors is significantly affected by tumor-derived or tumor-associated exosomes, which promote angiogenesis, increase the formation of cancer-associated fibroblast formation, and regulate the immune response [[99], [100], [101], [102]].

As important mediators in the crosstalk between stromal and tumor cells in the microenvironment, exomes have emerged, but molecular mechanism of breast cancer-derived exosomes in this environment and how this crosstalk operated with adipocytes remain unclear. When isolated from breast cancer cell culture supernatant by ultracentrifugation, exosomes were rich in miRNAs. One study of the miRNA profile analyzed HF-treated and untreated MCF-7 cells and exosomes [50]. Six of the miRNAs were abundant and sorted in exosomes. These findings supported the connections among HF treatment, exosome production, and MCF-7 cell proliferation. An experiment of miRNA knockdown in exosomes and an MCF-7 proliferation inhibition assay demonstrated that exosomal microRNA-31 (miR-31) attenuated MCF-7 cell growth because it targeted the histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2). As a result, the cyclin-dependent kinases 2 (CDK2) and cyclin D1 levels were both improved and p21 expression was attenuated. These results demonstrated that by inhibiting exosome production, exosomal miR-31 was reduced. By targeting the HDAC2, the level of cell cycle regulatory proteins was regulated, which improved the HF anticancer functions (Fig. 3). These findings point to a new role for HF and showed that exosome production in tumorigenesis may provide novel insight for the prevention and treatment of cancer.

Fig. 3.

Exosomal microRNA-31 (miR-31) in the tumor microenvironment (TME) was decreased by the inhibition of exosome production, thus targeting the amino acid metabolism and synthesis of ribosome and the histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2). It also manipulated the level of cell cycle regulatory proteins, making it beneficial to the anticancer functions of halofuginone (HF). miRNA: microRNAs; ETS1: erythroblast transformation specific 1; ELK1: erythroblast transformation specific domain-containing protein; DROSHA: anti-drosha/RNase III drosha; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; MYC: myelocytomatosis oncogene; XPO5: recombinant exportin 5; TRBP: TAR RNA-binding protein 2; KDM6A/6B: lysine-specific demethylase 6A/6B; TAP63: tumor protein 63; AGO2: argonaute RISC catalytic component 2; RISC: RNA-induced silencing complex; CDK2: cyclin-dependent kinase 2; HIF-1α: hypoxia inducible factor 1α; ZEB1: zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

2.5. Tumor immune microenvironment and the ECM

ECM components and stroma cells created an essential microenvironment for the development of tumors. Stroma cells limited tumor invasion with the addition HF, which inhibited TGF-β/Smad3 signaling, when combined with chemotherapy and on its own [51]. Additionally, amino acids, the components of proteins and the intermediate metabolites of various biosynthetic pathways, play an important metabolic function. Tumor cells and the tumor immune microenvironment were significantly affected by amino acid changes in metabolism. Popular cancer treatments target the metabolic process of tumor cells, in particular amino acid depletion therapy. This popular research topic has received a lot of attention recently. Similar research has shown that HF can cause two canonical integrated stress response (ISR) adaptations that attenuate bulk protein synthesis and reprogram gene expression. Because translation attenuation should be independent of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2a) and general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) phosphorylation, this is a surprising response. Pitera et al. [103] observed these HF activities, which provided the molecular basis for the selection of specific disease conditions to ensure optimal responsiveness. The proline-dependent cancer cells showed increased sensitivity to HF treatment [103]. After HF treatment, these changes were rescued upon the addition of proline, which indicated that they were the result of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS) inhibition. Because HF is a novel type of ATP-dependent inhibitor, it is often combined with prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS) to suppress ribosome formation, thus having a significant effect on the TME (Fig. 3). Kurata et al. [104] confirmed the use of ProRS as a novel therapeutic target in related genomic data. Preclinical data showed that a prolyl-aminoacylation blockade could trigger a pro-apoptotic response that was more complex than the canonical integrated stress response ProRS inhibition. Thus, this is new conduit that may be able to regular transcription and mRNA translation of proto-oncogenic factors as well as subsequent survival. Therefore, this therapeutic target holds significant interest.

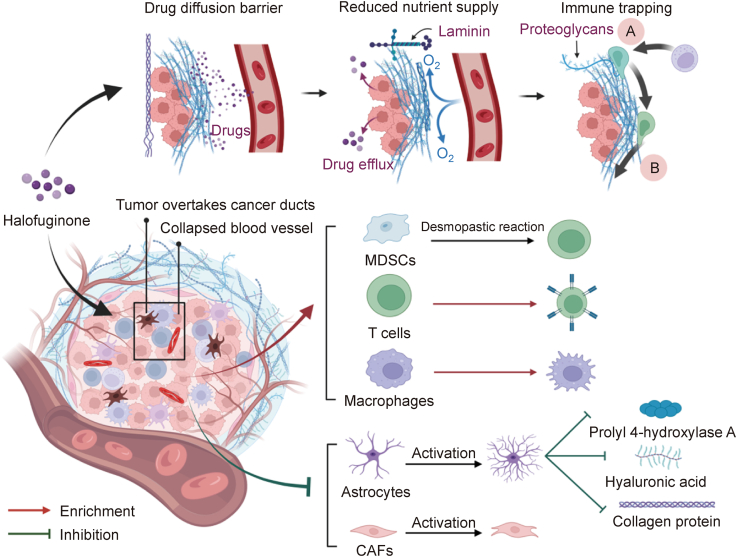

Abundant ECMs starting from cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) characterize most tumors. The collapse of the tumor's vascular system can be triggered by high collegen content, which can create a physical barrier that obstructs the ability of drug particles to penetrate and affect cytotoxic immune cells. CAFs can enrich tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) can be used to support a highly immunosuppressive TME [105]. HF can interrupt the collagen network in tumors and infiltate CD8+ T cells [104]. Research also has shown that HF can attenuate the beneficial effect of CAFs on oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cell invasion and migration. The inhibition of MMP-2 secretion and the upstream of TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling pathway are essential in these processes [106]. In addition, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) treatment combined with HF improved the immunosuppressive TME by deleting MDSCs, TAMs, and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Fig. 4). These important properties may be particularly important to Nrf2-activated cancers, which are characterized as being immune cold and having an immunosuppressive microenvironment [107]. Researchers have shown that Nrf2-activated cells are highly immunoedited in human cancer, thus enabling these cancerous cells to evade surveillance and progress into malignacies. As an Nrf2 inhibitor, HF can reduce the ability of NRF2-related cancer cells to resist for anticancer drugs, thus inhibiting cancers activated by Nrf2 and the formation of an immunologically cold TME.

Fig. 4.

By directly inhibiting the activation of stellate cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), halofuginone (HF) can reduce the deposition of collagen, hyaluronic acid, and prolyl 4-hydroxylase A, which are extracellular matrix (ECM) components that limit drug resistance pathways, improve the attractiveness of immune cells to cancer cell signals, augment drug release, and move along the ECM to access tumors. HF treatment blocked the collagen network in tumors by modulating the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), enriching the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and promoting Treg infiltration. MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Activated pancreas stellate cells (PSCs) in the pancreas are a source of ECM proteins. Spector et al. [22] evaluated the significance of PSC activation in establishing and developing tumors in mouse xenografts. The results showed that HF was able to inhibit development of subcutaneous tumor when it was implanted with matrigel and it could also limit collagen and levels of prolyl 4-hydroxylase A. Notably, the occurrence of ductal carcinoma of pancreatic cancer is closely related to fibrosis. Elahi-Gedwillo et al. [108], for example, found that by directly inhibiting the activation of pancreatic stellate cells, HF had significant antifibrotic activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). As a result, it limited the deposition of collagen and hyaluronic acid, which are components of ECM [109]. By decreasing fibroblast activation and reducing key ECM elements that drive stromal resistance, HF disrupted physical barriers to effective drug distribution in an autochthonous genetically engineered mouse model of PDA [108]. At the same time, following HF treatment, the immune landscape in PDA was altered and regions of low hyaluronan had greater immune infiltration. Thus, both classically activated inflammatory macrophages and cytotoxic T cells increased in number and in distribution (Fig. 4). According to these data, the critical, multifunctional role of the stroma in protection and survival of tumor demonstrated that compromising tumor integrity toward a normal physiological state using stroma-targeting therapy could be instrumental in the treatment of PDA.

2.6. Other mechanisms

In another study, the significance of HF in esophageal squamous carcinoma cell apoptosis was evaluated through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [6]. The results demonstrated that HF is inhibitory in ESCC cell apoptosis through PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent signaling. Later studies indicated that HF suppressed the growth of human uterine leiomyoma cells in a mouse xenograft model [110]. By inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and sarcoma (SRC) signaling pathways, HF slowed the growth of human uterine leiomyoma cells in a xenograft mice model [52]. Previous findings showed that chicken is an complementary model for studies that include pathophysiology of human uterine leiomyomas.

3. Combination therapy with radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy

Cancer has numerous subtypes that affect various tissues in multiple ways, making it a complex disease [53,54]. Numerous anticancer drugs have high toxicity and low efficacy, and prolonged use often leads to drug resistance. It is possible that most anticancer drugs have been designed to target a single protein or pathway, whereas incredibly complex combinations of deregulated signaling pathways often cause cancer [55]. Some combinations of anticancer drugs may have synergistic effects, presumably because they can target several pathways simultaneously. By following a multipronged effect, maximal therapeutic efficacy may be achieved with limited adverse side effects [[111], [112], [113]]. For more than 2,500 years, the cornerstone of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) herbal therapy has been combination therapy. Typically, formulas are used to prescribe herbs according to the distinct TCM theory. A formula generally includes a variety of herbs, each of which has several active ingredients that can target a specific aspect of the disease. By combining the primary active components from the herbs in a formula, it is possible that the results can be as or more effective than the single formula [35,114,115].

Anticancer synergism of artemisinin (ATS) and HF has been examined in cancer cell lines as well as in a xenograft nude mice model [114,115]. Results showed that the combination of ATS and HF suppressed more cells during the G1/G0 phase compared to either treatment alone. Additionally, the combination was able to trigger cell death because of the apoptosis and autophagy interaction in the CRC cells (Table 2) [9,52,54,[112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117]]. Additionally, results showed unprecedented evidence that HF may inhibit TGF-β/BMP signaling, and when combined with zoledronic acid, may inhibit breast cancer bone metastases [13]. These data further support the goal of the combination of HF with other therapies in manipulating the metastasis of breast cancer, which can reduce the mortality rate of breast cancer. Importantly, HF triggered synergistic cytotoxicity to inhibit the growth of multiple melanomas in combination with lenalidomide, melphalan, dexamethasone, and doxorubicin (Table 2) [116]. In addition, HF was utilized in combination therapy with radiation for lung cancer [112,117] and surgery for epithelial-like cancers [109]. HF also improved the antitumor impact of 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT) both in vivo and in vitro. Thus, HF may support the antitumor impact of ALA-PDT in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) because it could obstruct Nrf2 signaling [113]. Altogether, there is growing belief that combination therapy will be used with higher frequency in the treatment of tumors.

Table 2.

Synergistic efficacy of halofuginone (HF) in combination with other drugs or therapies.

| Types of cancers | Signal pathways | Other drugs or therapies | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | TGF-β/BMP | Zoledronic | [9] |

| Epithelial | / | Chemotherapy | [52] |

| Epithelial | / | Surgery | [52] |

| Breast | p21Cip1/p27Kip1 | ATS | [54] |

| Lung | / | Radiation therapy | [112] |

| cSCC | Nrf2/β-catenin and p-ERK1/2 | Photodynamic therapy | [113] |

| Colorectal | p21Cip1/p27Kip1 | ATS | [114] |

| Melanoma | p21Cip1/p27Kip1 | ATS | [114] |

| Liver | p21Cip1/p27Kip1 | ATS | [114] |

| Colorectal | Apoptosis and autophagy | ATS | [115] |

| MM | P38-MAPK/c-Jun | Dexamethasone | [116] |

| MM | P38-MAPK/JNK | Doxorubicin | [116] |

| MM | P38-MAPK/p53 | Lenalidomide | [116] |

| MM | P38-MAPK/Hsp-27 | Melphalan | [116] |

| Lung | / | Radiation therapy | [117] |

/: no signaling pathway existing. TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; ATS: artemisinin; cSCC: cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; p-ERK1/2: p-extracellular regulated kinase 2; MM: multiple myeloma; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

4. Limitations and challenges

Although previous studies have examined the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of HF in Fischer 344 rats and CD2F1 mice [118], HF has not been observed in plasma after oral administration, which indicated that oral bioavailability may be limited. Preclinical studies have not detected the oral bioavailability of HF in the liver, lung, breast, intestine, or brain. According to a phase I and pharmacokinetic study of HF on patients with advanced solid tumors [4], the recommended dose for chronic administration was 0.5 mg/day. Several patients experienced bleeding complications after the HF treatment; however, a causal relationship was not ruled out. In this study, the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) of HF included vomiting, nausea, and fatigue. For phase II studies on HF, the recommended dose is 0.5 mg/day, administered orally.

HF is poorly soluble in water, and as a result, its tissue permeability, bioavailability, and clinical efficacy are affected. Given these findings, we further investigated the solution of the declined toxicity of HF and enhanced oral bioavailability via enhancing the clinical therapeutic potential. When we compared other drug delivery systems, nanocarriers were found to have multiple advantages like targeting, low toxicity, and a longer action time as well as a greater capacity for drug-loading. These findings may provide new insights into nano formulation. Because of their higher drug-loading, EPR effect, ability to overcome multidrug resistance (MDR), improved bioavailability, and facile surface functionalization, HF-loaded d-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS) polymeric micelles (PMs) (HTPM) have been receiving a lot more attention. As nanotechnology and nanoscience continue to advance, the development of HTPM has been further facilitated, thus providing an important research direction to explore HF thanks to its structure and ability to improve therapeutic effects while also reducing systemic toxicity. Similar studies have shown that HF loaded onto nanodelivery materials, such as a novel nano-formulation, enhanced intratumor delivery and ameliorated tumor hypoxia. As a result, it revealed its synergetic radiation, which improved cancer-killing effects, remodeled the tumor stroma, and boosted antitumor immunity when used in a combined treatment [119,120]. Another study developed a theranostic nanoplatform and loaded HF onto the mPt (polyethylene glycol-coated mesoporous platinum loaded with halofuginone (PEG@mPt-HF)) for ECM remodeling. This new model decreased systematic toxicity significantly and improved the therapeutic effect by combining treatments [121]. HF micelle nanoparticles nearly stopped the systemic toxicity that typically is exhibited by free HF while also retaining its tumor-suppressive properties [122].

With the increase in the study of drug chemical structure-disease interactions in recent years, HF could act on tumor targets via altering pivotal groups owing to its cis-trans isomerism. Moreover, new targets for HF can also be developed so that it can better deal with tumors. HF can be altered using a variety of methods, including the addition of drug delivery carriers and linked target molecules to reduce toxicity. In addition, strategies and methods using HF for the treatment of diseases such as protozoan infection, fibrosis, and autoimmune diseases can also be improved for the treatment of cancers.

A combination of therapeutic methods like synergistic photodynamic therapy and immune therapy with HF can enhance HF biofunction and improve antitumor effects. This promising strategy can be used to overcome the deactivation pathways during HF treatment and thus is a suitable option for its ability to serve as an anticancer agent.

5. Conclusions

HF is a so-called magic bullet that has been derived from febrifugine. It has a marked influence on the inhibition of Smad3 phosphorylation downstream of the TGF-β signaling pathway. As a result, it can inhibit fibrosis with Nrf2 accumulation and F-actin augmentation. Additionally, HF activated ULK1 by inducing downregulation of its phosphorylation site through crosstalk combined with Akt/mTORC1 and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to induce autophagic flux under conditions that were nutrient rich. HF also induced the inhibition of the production of exosomes and limited exosomal miR-31 in the TME, thus blocking amino acid metabolism and ribosome synthesis. By modulating the immunosuppressive TME, HF treatment significantly disrupted the collagen network in tumors, including TAM and MDSC enrichment and promotion of Treg infiltration. Taken together, our data provide unprecedented evidence that HF can be utilized as a drug to effectively treat numerous cancers.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Runan Zuo: Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Xinyi Guo: Validation, Resources. Xinhao Song: Visualization, Investigation. Xiuge Gao: Supervision, Investigation. Junren Zhang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Shanxiang Jiang: Formal analysis. Vojtech Adam: Data curation. Kamil Kuca: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wenda Wu: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Dawei Guo: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 32172918), the project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, China, and the Key Projects of Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Provincial Department of Education, China (Grant No.: 2023AH051017) and the Anhui Agricultural University Talent Research Grant Project (Project No.: RC393302). We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com.cn) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kamil Kuca, Email: kamil.kuca@uhk.cz.

Wenda Wu, Email: wuwenda@hfut.edu.cn, bzwh@163.com.

Dawei Guo, Email: gdawei0123@njau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lan L.H., Sun B.B., Zuo B.X.Z., et al. Prevalence and drug resistance of avian Eimeria species in broiler chicken farms of Zhejiang province, China. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:2104–2109. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang D., Sun B., Yue Y., et al. Anticoccidial effect of halofuginone hydrobromide against Eimeria tenella with associated histology. Parasitol. Res. 2012;111:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia X., Wang L., Zhang X., et al. Halofuginone-induced autophagy suppresses the migration and invasion of MCF-7 cells via regulation of STMN1 and p53. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018;119:4009–4020. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jonge M.J.A., Dumez H., Verweij J., et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of halofuginone, an oral quinazolinone derivative in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer. 2006;42:1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H., Zhang Y., Lan X., et al. Halofuginone sensitizes lung cancer organoids to cisplatin via suppressing PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.773048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo J., Zhang S., Wang J., et al. Hinokiflavone inhibits growth of esophageal squamous cancer by inducing apoptosis via regulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.833719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Figueiredo-Pontes L.L., Assis P.A., Santana-Lemos B.A.A., et al. Halofuginone has anti-proliferative effects in acute promyelocytic leukemia by modulating the transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mi L., Liu J., Zhang Y., et al. The EPRS-ATF4-COLI pathway axis is a potential target for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma therapy. Phytomedicine. 2024;129 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karagiannis G.S., Pastoriza J.M., Wang Y., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces breast cancer metastasis through a TMEM-mediated mechanism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y.S., Jalgaonkar S.P., Middleton J.D., et al. Stress-inducible gene Atf3 in the noncancer host cells contributes to chemotherapy-exacerbated breast cancer metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2017;114:E7159–7168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700455114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuo R., Zhang J., Song X., et al. Encapsulating halofuginone hydrobromide in TPGS polymeric micelles enhances efficacy against triple-negative breast cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021;16:1587–1600. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S289096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkin M., Ariel I., Miao H.Q., et al. Inhibition of bladder carcinoma angiogenesis, stromal support, and tumor growth by halofuginone. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4111–4118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taras D., Blanc J.F., Rullier A., et al. Halofuginone suppresses the lung metastasis of chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats through MMP inhibition. Neoplasia. 2006;8:312–318. doi: 10.1593/neo.05796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramovitch R., Dafni H., Neeman M., et al. Inhibition of neovascularization and tumor growth, and facilitation of wound repair, by halofuginone, an inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis. Neoplasia. 1999;1:321–329. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yee K.O., Connolly C.M., Pines M., et al. Halofuginone inhibits tumor growth in the polyoma middle T antigen mouse via a thrombospondin-1 independent mechanism. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006;5:218–224. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.2.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abramovitch R., Itzik A., Harel H., et al. Halofuginone inhibits angiogenesis and growth in implanted metastatic rat brain tumor model: An MRI study. Neoplasia. 2004;6:480–489. doi: 10.1593/neo.03520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross D.J., Reibstein I., Weiss L., et al. Treatment with halofuginone results in marked growth inhibition of a von Hippel-Lindau pheochromocytoma in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:3788–3793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagler A., Ohana M., Shibolet O., et al. Suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice by the alkaloid coccidiostat halofuginone. Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;40:1397–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinthus J.H., Sheffer Y., Nagler A., et al. Inhibition of Wilms tumor xenograft progression by halofuginone is accompanied by activation of WT-1 gene expression. J. Urol. 2005;174:1527–1531. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000179218.16587.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavish Z., Pinthus J.H., Barak V., et al. Growth inhibition of prostate cancer xenografts by halofuginone. Prostate. 2002;51:73–83. doi: 10.1002/pros.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spector I., Honig H., Kawada N., et al. Inhibition of pancreatic stellate cell activation by halofuginone prevents pancreatic xenograft tumor development. Pancreas. 2010;39:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181da8aa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook J.A., Choudhuri R., Degraff W., et al. Halofuginone enhances the radiation sensitivity of human tumor cell lines. Cancer. Lett. 2010;289:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuchida K., Tsujita T., Hayashi M., et al. Halofuginone enhances the chemo-sensitivity of cancer cells by suppressing NRF2 accumulation, Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;103:236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demiroglu-Zergeroglu A., Turhal G., Topal H., et al. Anticarcinogenic effects of halofuginone on lung-derived cancer cells, Cell Biol. Int. 2020;44:1934–1944. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y., Liu W., Wang P., et al. Halofuginone inhibits radiotherapy-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:71341–71352. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flanders K.C. Smad3 as a mediator of the fibrotic response. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2004;85:47–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin R., Yi S., Gong L., et al. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling with halofuginone can enhance the antitumor effect of irradiation in Lewis lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2015;8:3549–3559. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S92518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ando K., Heymann M.F., Stresing V., et al. Current therapeutic strategies and novel approaches in osteosarcoma. Cancers. 2013;5:591–616. doi: 10.3390/cancers5020591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamora A., Mullard M., Amiaud J., et al. Anticancer activity of halofuginone in a preclinical model of osteosarcoma: Inhibition of tumor growth and lung metastases. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14413–14427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juárez P., Mohammad K.S., Yin J.J., et al. Halofuginone inhibits the establishment and progression of melanoma bone metastases. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6247–6256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pines M. Targeting TGFβ signaling to inhibit fibroblast activation as a therapy for fibrosis and cancer: Effect of halofuginone. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2008;3:11–20. doi: 10.1517/17460441.3.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto R., Hamada S., Tanaka Y., et al. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 depletion sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine via aldehyde dehydrogenase 3a1 repression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021;379:33–40. doi: 10.1124/jpet.121.000744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z., Singh R., Aschner M. Methods for the detection of autophagy in mammalian cells. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2016;69:21–26. doi: 10.1002/cptx.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White E. Deconvoluting thecontext-dependentrole for autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimmelman A.C. The dynamic nature of autophagy in cancer. Genes. Dev. 2011;25:1999–2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.17558811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen G., Gong R., Yang D., et al. Halofuginone dually regulates autophagic flux through nutrient-sensing pathways in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2789. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu Y., Le Leu R.K., Young G.P. Sulindac corrects defective apoptosis and suppresses azoxymethane-induced colonic oncogenesis in p53 knockout mice. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;116:870–875. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knox S.S. From ‘omics’ to complex disease: A systems biology approach to gene-environment interactions in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang L., Li F., Sheng J., et al. DrugComboRanker: Drug combination discovery based on target network analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:i228–i236. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhan H.X., Wang Y., Li C., et al. LincRNA-ROR promotes invasion, metastasis and tumor growth in pancreatic cancer through activating ZEB1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;374:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X., Luo G., Zhang K., et al. Hypoxic tumor-derived exosomal miR-301a mediates M2 macrophage polarization via PTEN/PI3Kγ to promote pancreatic cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4586–4598. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mincheva-Nilsson L., Baranov V. Cancer exosomes and NKG2D receptor-ligand interactions: Impairing NKG2D-mediated cytotoxicity and anti-tumour immune surveillance. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014;28:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardin H., Helein H., Meyer K., et al. Thyroid cancer stem-like cell exosomes: Regulation of EMT via transfer of lncRNAs. Lab. Invest. 2018;98:1133–1142. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boelens M.C., Wu T.J., Nabet B.Y., et al. Exosome transfer from stromal to breast cancer cells regulates therapy resistance pathways. Cell. 2014;159:499–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hergenreider E., Heydt S., Tréguer K., et al. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:249–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halkein J., Tabruyn S.P., Ricke-Hoch M., et al. microRNA-146a is a therapeutic target and biomarker for peripartum cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:2143–2154. doi: 10.1172/JCI64365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mittelbrunn M., Gutiérrez-Vázquez C., Villarroya-Beltri C., et al. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia X., Wang X., Zhang S., et al. miR-31 shuttled by halofuginone-induced exosomes suppresses MFC-7 cell proliferation by modulating the HDAC2/cell cycle signaling axis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:18970–18984. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spector I., Zilberstein Y., Lavy A., et al. Involvement of host stroma cells and tissue fibrosis in pancreatic tumor development in transgenic mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin J., Wu X. Halofuginone inhibits cell proliferation and AKT/mTORC1 signaling in uterine leiomyoma cells. Growth. Factors. 2022;40:212–220. doi: 10.1080/08977194.2022.2113394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Machado S.A., Bahr J.M., Hales D.B., et al. Validation of the aging hen (Gallus gallus domesticus) as an animal model for uterine leiomyomas. Biol. Reprod. 2012;87:86. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.101188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azmi A.S., Wang Z., Philip P.A., et al. Proof of concept: Network and systems biology approaches aid in the discovery of potent anticancer drug combinations. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3137–3144. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun Y., Sheng Z., Ma C., et al. Combining genomic and network characteristics for extended capability in predicting synergistic drugs for cancer. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8481. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Betti M., Aspesi A., Sculco M., et al. Genetic predisposition for malignant mesothelioma: A concise review. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019;781:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okusaka T., Furuse J. Recent advances in chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer: Evidence from Japan and recommendations in guidelines. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;55:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s00535-020-01666-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin A., Jung K.W., Won Y.J. Colorectal cancer mortality in Hong Kong of China, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:979–983. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markowitz S.D., Bertagnolli M.M. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abotaleb M., Kubatka P., Caprnda M., et al. Chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: An update. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2018;101:458–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei Y., Li M., Cui S., et al. Shikonin inhibits the proliferation of human breast cancer cells by reducing tumor-derived exosomes. Molecules. 2016;21:777. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin Y., Cai X., Chen X., et al. Tumor-secreted miR-214 induces regulatory T cells: A major link between immune evasion and tumor growth. Cell Res. 2014;24:1164–1180. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Panitch H.S., Hirsch R.L., Haley A.S., et al. Exacerbations of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with gamma interferon. Lancet. 1987;1:893–895. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boehm U., Klamp T., Groot M., et al. Cellular responses to interferon-gamma. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maher S.G., Romero-Weaver A.L., Scarzello A.J., et al. Interferon: Cellular executioner or white knight? Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:1279–1289. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin M.L., Park S.Y., Kim Y.H., et al. Halofuginone induces the apoptosis of breast cancer cells and inhibits migration via downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int. J. Oncol. 2014;44:309–318. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Juárez P., Fournier P.G.J., Mohammad K.S., et al. Halofuginone inhibits TGF-β/BMP signaling and in combination with zoledronic acid enhances inhibition of breast cancer bone metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:86447–86462. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alby L., Auerbach R. Differential adhesion of tumor cells to capillary endothelial cells in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1984;81:5739–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nicolson G.L. Cancer metastasis: Tumor cell and host organ properties important in metastasis to specific secondary sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;948:175–224. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(88)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen G., Tang C., Shi X., et al. Halofuginone inhibits colorectal cancer growth through suppression of Akt/mTORC1 signaling and glucose metabolism. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24148–24162. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pauli B.U., Lee C.L. Organ preference of metastasis. The role of organ-specifically modulated endothelial cells. Lab. Invest. 1988;58:379–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramani V.C., Lemaire C.A., Triboulet M., et al. Investigating circulating tumor cells and distant metastases in patient-derived orthotopic xenograft models of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:98. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Q., Hodge J., Wang J., et al. Emodin reduces Breast Cancer Lung Metastasis by suppressing Macrophage-induced Breast Cancer Cell Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and Cancer Stem Cell formation. Theranostics. 2020;10:8365–8381. doi: 10.7150/thno.45395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiao Y., Cong M., Li J., et al. Cathepsin C promotes breast cancer lung metastasis by modulating neutrophil infiltration and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:423–437.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin L., Han B., Siegel E., et al. Breast cancer lung metastasis: Molecular biology and therapeutic implications. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2018;19:858–868. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2018.1456599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phillips C., Jeffree R., Khasraw M. Management of breast cancer brain metastases: A practical review. Breast Edinb. Scotl. 2017;31:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Altundag K. Characteristics of breast cancer patients with brain metastases who live longer than 18 months. Breast Edinb. Scotl. 2017;34:132–133. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Izutsu N., Kinoshita M., Ozaki T., et al. Cerebellar preference of luminal A and B type and basal ganglial preference of HER2-positive type breast cancer-derived brain metastases. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2021;15:175. doi: 10.3892/mco.2021.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kotecki N., Lefranc F., Devriendt D., et al. Therapy of breast cancer brain metastases: Challenges, emerging treatments and perspectives. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018;10 doi: 10.1177/1758835918780312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boix-Montesinos P., Soriano-Teruel P.M., Armiñán A., et al. The past, present, and future of breast cancer models for nanomedicine development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;173:306–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ottaviani G., Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat. Res. 2009;152:3–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dass C.R., Ek E.T., Contreras K.G., et al. A novel orthotopic murine model provides insights into cellular and molecular characteristics contributing to human osteosarcoma. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2006;23:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geyer M., Gaul L.-M., D Agosto S.L., et al. The tumor stroma influences immune cell distribution and recruitment in a PDAC-on-a-chip model. Front. Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1155085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kalra H., Drummen G.P.C., Mathivanan S. Focus on extracellular vesicles: Introducing the next small big thing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:170. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tkach M., Théry C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: Where we are and where we need to go. Cell. 2016;164:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kowal J., Tkach M., Théry C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;29:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Théry C., Zitvogel L., Amigorena S. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahaweni N.M., Kaijen-Lambers M.E., Dekkers J., et al. Tumour-derived exosomes as antigen delivery carriers in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for malignant mesothelioma. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2013;2 doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wolfers J., Lozier A., Raposo G., et al. Tumor-derived exosomes are a source of shared tumor rejection antigens for CTL cross-priming. Nat. Med. 2001;7:297–303. doi: 10.1038/85438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.André F., Schartz N.E.C., Chaput N., et al. Tumor-derived exosomes: A new source of tumor rejection antigens. Vaccine. 2002;20:A28–A31. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Clayton A., Mason M.D. Exosomes in tumour immunity. Curr. Oncol. 2009;16:46–49. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cordonnier M., Chanteloup G., Isambert N., et al. Exosomes in cancer theranostic: Diamonds in the rough, Cell Adh. Migr. 2017;11:151–163. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1250999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prud’homme G.J. Pathobiology of transforming growth factor beta in cancer, fibrosis and immunologic disease, and therapeutic considerations. Lab. Invest. 2007;87:1077–1091. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barros F.M., Carneiro F., Machado J.C., et al. Exosomes and immune response in cancer: Friends or foes? Front. Immunol. 2018;9:730. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu R., Greening D.W., Zhu H., et al. Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: Toward clinical application. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:1152–1162. doi: 10.1172/JCI81129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Choi D.S., Kim D.K., Kim Y.K., et al. Proteomics, transcriptomics and lipidomics of exosomes and ectosomes. Proteomics. 2013;13:1554–1571. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hewson C., Morris K.V. Form and function of exosome-associated long non-coding RNAs in cancer. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016;394:41–56. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan S., Xia L., Yi P., et al. Exosomal miRNAs in tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;39:67. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kahlert C., Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J. Mol. Med. 2013;91:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kucharzewska P., Belting M. Emerging roles of extracellular vesicles in the adaptive response of tumour cells to microenvironmental stress. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2013;2 doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Webber J., Steadman R., Mason M.D., et al. Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9621–9630. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhuang G., Wu X., Jiang Z., et al. Tumour-secreted miR-9 promotes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis by activating the JAK-STAT pathway. EMBO J. 2012;31:3513–3523. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pitera A.P., Szaruga M., Peak-Chew S.Y., et al. Cellular responses to halofuginone reveal a vulnerability of the GCN2 branch of the integrated stress response. EMBO J. 2022;41 doi: 10.15252/embj.2021109985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kurata K., James-Bott A., Tye M.A., et al. Prolyl-tRNA synthetase as a novel therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:12. doi: 10.1038/s41408-023-00787-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen Y., Hu S., Shu Y., et al. Antifibrotic therapy augments the antitumor effects of vesicular stomatitis virus via reprogramming tumor microenvironment. Hum. Gene Ther. 2022;33:237–249. doi: 10.1089/hum.2021.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang D., Tian M., Fu Y., et al. Halofuginone inhibits tumor migration and invasion by affecting cancer-associated fibroblasts in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1056337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Baird L., Yamamoto M. Immunoediting of KEAP1-NRF2 mutant tumours is required to circumvent NRF2-mediated immune surveillance. Redox. Biol. 2023;67 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Elahi-Gedwillo K.Y., Carlson M., Zettervall J., et al. Antifibrotic therapy disrupts stromal barriers and modulates the immune landscape in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:372–386. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huang H., Brekken R.A. The next wave of stroma-targeting therapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:328–330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Koohestani F., Qiang W., MacNeill A.L., et al. Halofuginone suppresses growth of human uterine leiomyoma cells in a mouse xenograft model. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31:1540–1551. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang L., Zhou G., Liu P., et al. Dissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal formula Realgar-Indigo naturalis as an effective treatment for promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4826–4831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712365105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang H., Shen D., Xu H., et al. A new strategy in drug design of Chinese medicine: Theory, method and techniques, Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2012;18:803–806. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lv T., Huang J., Wu M., et al. Halofuginone enhances the anti-tumor effect of ALA-PDT by suppressing NRF2 signaling in cSCC. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022;37 doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen G., Gong R., Shi X., et al. Halofuginone and artemisinin synergistically arrest cancer cells at the G1/G0 phase by upregulating p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:50302–50314. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gong R., Yang D., Kwan H.Y., et al. Cell death mechanisms induced by synergistic effects of halofuginone and artemisinin in colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022;19:175–185. doi: 10.7150/ijms.66737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Leiba M., Jakubikova J., Klippel S., et al. Halofuginone inhibits multiple myeloma growth in vitro and in vivo and enhances cytotoxicity of conventional and novel agents. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;157:718–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mi L., Zhang Y., Su A., et al. Halofuginone for cancer treatment: A systematic review of efficacy and molecular mechanisms. J. Func. Foods. 2022;98 [Google Scholar]

- 118.Stecklair K.P., Hamburger D.R., Egorin M.J., et al. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of halofuginone (NSC 713205) in CD2F1 mice and Fischer 344 rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2001;48:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s002800100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gong X., Li J., Xu X., et al. Microvesicle-inspired oxygen-delivering nanosystem potentiates radiotherapy-mediated modulation of tumor stroma and antitumor immunity. Biomaterials. 2022;290 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yu N., Zhang X., Zhong H., et al. Stromal homeostasis-restoring nanomedicine enhances pancreatic cancer chemotherapy. Nano Lett. 2022;22:8744–8754. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c03663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang J., Xu Z., Li Y., et al. Theranostic mesoporous platinum nanoplatform delivers halofuginone to remodel extracellular matrix of breast cancer without systematic toxicity. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022;8 doi: 10.1002/btm2.10427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Panda H., Suzuki M., Naito M., et al. Halofuginone micelle nanoparticles eradicate Nrf2-activated lung adenocarcinoma without systemic toxicity. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2022;187:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]