Abstract

Introduction Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks through the nasal cavity occurrence has a rising trend, of which primary spontaneous leak is 6 to 40% of all the CSF leaks. The most common site of CSF leak is ethmoid roof where the bone is thinner in the entire skull base. Clivus being the hard bone is a rare site for spontaneous leak. We present a case series from a single quaternary care center of this rare occurrence and study its reason and management strategy.

Materials and Methods A retrospective surgical audit over a period of 10 years of all patients diagnosed with CSF rhinorrhea was done. A PubMed search was conducted with keywords of CSF leak, CSF rhinorrhea, spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea, clival leak, and clivus to identify the literature and these articles were compiled and their management reviewed.

Results and Analysis A total of 100 patients underwent surgical management for spontaneous CSF leak, of which there were 5 patients who had spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea from the clivus. There were four female patients; four patients had high body mass index. The most common site of leak was mid-clivus and surgical technique employed was multilayer dural plasty with a nasoseptal flap and measures were taken to reduce the intracranial pressure intra-operatively and postoperatively.

Conclusion Spontaneous clival leak is a rare entity with mid and lower clivus being the common site. A combined approach by ENT and neurosurgeons results in best outcome for the patients.

Keywords: spontaneous clival leaks, clivus, spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea, IIH

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea occurring spontaneously has a greater propensity to develop meningitis and intracranial complications. 1 Primary spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea accounts for 6 to 40% of all CSF leaks. 2 The etiology for these spontaneous CSF leaks can be congenital or due to erosions from arachnoid granulations, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), or a combination of these processes. Omaya postulated that there are areas of focal atrophy, which result in CSF outpouches. 3 Eventually, when the CSF pressure increases, these pouches enlarge causing erosion of the underlying bone and tears causing CSF leak. 1 4 The most common sites of spontaneous leak in the anterior skull base are the cribriform plate, fovea ethmoidalis, and planum sphenoid 5 in descending order of occurrence. These sites are inherently weak and therefore may explain the occurrence of leaks in these regions. Unlike the cribriform plate, the clival bone is thick; therefore, leaks from this region are relatively rare. Identifying these leaks and managing them pose a challenge to both the expert and the novice.

In this study, we report a series of five patients with spontaneous clival CSF leaks and discuss their tailored management in terms of identification and surgical closure.

Methodology

A retrospective surgical audit was conducted for patients diagnosed and managed with CSF rhinorrhea in a referral center in South India over the past 10 years (2011–2021). Institutional review board clearance was obtained (IRB no:14457). Inclusion criteria included patients with clival site leak alone, and details about possible etiological features, management strategies, and the challenges encountered during surgery were collected. We excluded patients with a prior history of skull base surgery or skull base tumors. Data about demographics, presenting symptoms, comorbidities, relevant history, and body mass index (BMI) were analyzed. Preoperative assessment data included clinical examination, ophthalmic examination, radiological imaging, i.e., high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) including DRIVE sequences and MR venogram), and direct measurement of intrathecal pressure with a lumbar puncture. As an institutional protocol, we do not routinely recommend cisternograms to identify the site of the leak, instead, the radiological protocol is designed to pick very subtle leaks and intra-operative fluorescein is used for direct visualization of the leak site.

A PubMed search was conducted with the keywords CSF leak, CSF rhinorrhea, spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea, clival leak, and clivus to identify the studies reporting case(s) of spontaneous CSF leak from the clivus.

Results and Analysis

A total of 100 patients were diagnosed at our center with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea and underwent surgical management in the past 10 years by the Skull Base surgery team. Five patients with CSF rhinorrhea secondary to bony defects in the clivus were identified. In our series, there was a female preponderance (4:1) with the mean age of presentation being 54 years. The duration of symptoms before these patients sought medical attention ranged from 4 months to 7 years. Three patients had features of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and three patients had a previous history of meningitis ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Clinical and radiological features.

| Cases | Age (y) | Sex | Comorbidities | BMI | ICP measured (cm of water) | Imaging features of raised ICP | Ophthalmology | Type of repair | ICP management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | M | HTN | 31.7 | 13 (pre-repair) 23 (post-repair) |

Bilateral peri-optic flare, tortuous optic nerves | Papilledema | Multilayer (primary surgery) Bath plug, nasoseptal flap (second surgery) |

TP shunt | Recurrence No failure/recurrence (after revision repair) |

| 2 | 50 | F | – | 21.5 | 12 | No features of raised ICP | No papilledema | Multilayer with nasoseptal flap | Perioperative lumbar drain | No failure/recurrence |

| 3 | 56 | F | – | 32 | 18 | Skull base attenuation, empty sella | No papilledema | Multilayer with nasoseptal flap | Perioperative lumbar drain, Postoperative acetazolamide | No failure/recurrence |

| 4 | 53 | F | HTN, DM | 33.3 | 15 | Empty sella | No papilledema | Multilayer with nasoseptal flap | Perioperative lumbar drain, Postoperative acetazolamide | No failure/recurrence |

| 5 | 52 | F | HTN | 30.6 | 23 | Multilayer with nasoseptal flap | TP shunt | No failure/recurrence |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, systemic hypertension; ICP, intracranial pressure.

Surgical Technique

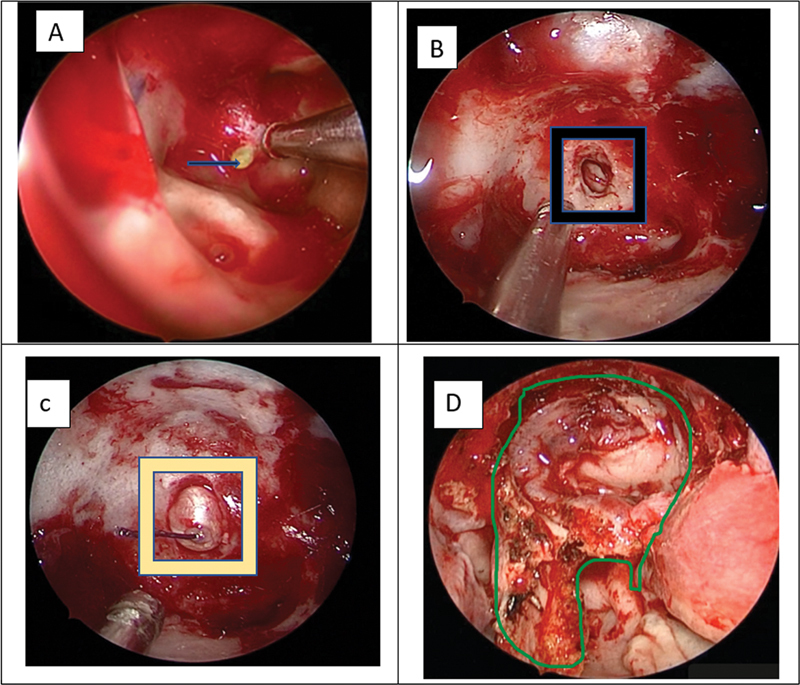

All patients had a preoperative measurement of CSF pressure routinely on the surgical table before surgery either before or after induction. The patient was taken under general anesthesia and the nasal cavity was decongested using 0.1% adrenaline with saline for 10 minutes before surgery. The surgical steps included posterior septotomy and bilateral wide sphenoidotomy followed by harvesting a vascular pedicled nasoseptal flap (Hadad–Bassagasteguy flap). The site of the CSF leak was identified, and the bony margins of the leak site were delineated. If the site of the leak was not evident, 1% intrathecal fluorescein was used to identify the site of the leak. In addition, 1 mL of 20% fluorescein was diluted in 3 mL of saline, 8 units of this solution were taken in an insulin syringe and diluted in 10 mL of saline. The dilute fluorescein is injected intrathecally over 10 minutes. A zero-degree endoscope with a blue filter was used to identify the site of the leak. The average size of the defect was 5 mm × 5 mm and there was no drilling of bone around the defect. A multilayer duraplasty was performed using fascia lata that was harvested for this purpose and the first layer of fascia lata was placed through the defect as an intradural repair. The second layer was placed between the dura and the bone with fat if there was sufficient space after lifting the dura from the surrounding bone. The third layer is an onlay fascia lata which was reinforced with a nasoseptal flap and surgicel and gelfoam. In four out of five patients, this underlay technique was achieved. An overlay technique was employed for the patient where underlay could be done due to the presence of a basilar artery close to the bony margins. The multilayer closure included fascia lata, and thigh fat which was superimposed with gelfoam and surgicel. Nasal packing was done with nonabsorbable gelfoam packs ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

( A ) The blue arrow shows the endoscopic image of fluorescein through the clival defect. ( B ) The black square box shows the bony defect in the clivus. ( C ) The yellow square shows the bony defect sealed with fat and fascia as an inlay layer. ( D ) Reconstruction with multilayered dural plasty showing reinforcement with nasoseptal flap with green highlighter.

Postoperative Period

All patients received antibiotics and were advised to apply saline nasal spray after nasal pack removal on the 5th day PO as part of routine nasal surgery and were evaluated at 1 week and 3 months in the postoperative period in the out-patient clinic which included clinical history and nasal endoscopic examination and cleaning of crust in the nasal passage. The follow-up period ranged from 3 months to 7 years. None of these patients had any recurrence of the leak.

Discussion

Spontaneous CSF leaks in the clival region of the sphenoid are a rare occurrence. A PubMed search was conducted with the keywords CSF leak, CSF rhinorrhea, spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea, clival leak, and clivus to identify the studies reporting case(s) of spontaneous CSF leak from the clivus ( Table 2 ). Of these 19 studies, the largest series was of six patients and the present series from India is probably due to the center being a large referral center in South East Asia. There is also an increasing trend in the number of skull base defects seen especially among obese middle-aged females in whom there is an increased risk of benign intracranial hypertension. 2 Four of the five cases in our series were postmenopausal women. Menopause with its associated decrease in bone density and osteoporosis has been considered a predisposing factor. 6

Table 2. Literature review for spontaneous CSF clival leaks.

| Author (first author) | Year | No. of cases | Predisposing factor(s) | Site of clival defect | Repair approach | Repair technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lockwood 34 | 1980 | 1 | Postmenopausal female | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Trans-sphenoid | Freeze dried dura + bone plug. |

| Coiteiro et al 15 | 1995 | 2 | Postmenopausal female (1 case) Saxophone player (1 case) Basilar artery pulsations against dural defect |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Trans-sphenoid | Muscle, bone Perioperative lumbar drain |

| Turanzas et al 35 | 1996 | 1 | Postmenopausal female | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Fat |

| Al-Shurbaji 36 | 2005 | 1 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer |

| Ramos et al 12 | 2007 | 1 | Marfan's syndrome | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Fat, tissue glue |

| Ahmad 37 | 2008 | 2 | Basilar artery pulsations against dural defect (1 case) |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid (1 case) Sublabial trans-sphenoid (1 case) |

Fat, fascia, tissue glue Muscle piece, fascia, fibrin glue |

| Akyuz 38 | 2008 | 1 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Fat, fascia lata, tissue glue |

| Elrahaman 39 | 2009 | 2 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Fat, tissue glue |

| Van Zele 40 | 2013 | 6 | Postmenopausal female (3 cases) Raised ICP (2 cases) |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer repair, Nonvascularized tissue (3 cases) Nasoseptal flap (3 cases) Thecoperitoneal shunt (2 cases) |

| Tandon 41 | 2014 | 1 | Empty sella | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Sublabial trans-sphenoid | Fat, fascia lata, tissue glue Perioperative lumbar drain |

| Zanabria-Ortiz 42 | 2015 | 1 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Trans-nasal trans-sphenoid | Fat, tissue glue |

| Hayashi 43 | 2015 | 1 | Skull base attenuation Multiple clival defects in pneumatized dorsum sellae |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer repair with pedicled nasoseptal flap Perioperative lumbar drain |

| Pagella 44 | 2016 | 6 | Postmenopausal female (5 cases) High BMI (3 cases) Measured ICP: normal |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer repair Fascia, middle turbinate mucosa (3 cases) Nasoseptal flap (3 cases) |

| Codina Aroca 45 | 2017 | 2 | Postmenopausal female (1 case) |

Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer repair with fascia, nasoseptal flap Perioperative lumbar drain (1 case) |

| Asad 46 | 2017 | 1 | Postmenopausal female | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Nonvascularized fascia + fat Perioperative lumbar drain |

| Karli 47 | 2018 | 1 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Temporal fascia, turbinate bone, fat, tissue glue |

| Chen GY 48 | 2018 | 1 | – | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multilayer repair with fascia, fat, nasoseptal flap |

| Nogueira 49 | 2019 | 1 | Hypothyroid, middle-aged female | Mid-clivus (posterior wall of sphenoid) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Vascularized nasoseptal flap |

| Khairy et al 9 | 2019 | 1 | Canalis basilaris medianus | Lower clivus (Basiocciput, anterior to foramen magnum) |

Endoscopic transnasal approach to clivus | Fascia lata graft |

| Our study | 2021 | 4 | Postmenopausal female (3 cases) High BMI (3 cases) Raised ICP (3 cases) |

Mid-clivus (posterior sphenoid wall) | Transnasal trans-sphenoid | Multi-layered repair (fat, fascia lata) and pedicled nasoseptal flap |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ICP, intracranial pressure.

Etiological Factors

Among the many factors suggested as causes for clival leaks, the presence of IIH was a common occurrence in this series. Even though congenital or developmental defects in the clivus may be attributed to defects in the body of sphenoid formed at birth due to the incomplete fusion of pre- and post-sphenoid centers of ossification. Basisphenoid is separated from basiocciput by spheno-occipital synchondrosis, which closes by 17 years of age by enchondral ossification. Dehiscence in these areas of fusion could explain a development defect. 7 In addition, 5% of the 138 sphenoid bones examined by Hooper had a defect connecting the sphenoid sinus to the cranial base. 8 Leaks through a “persistent craniopharyngeal canal” and canalis basilaris medianus have also been reported. 9

Excessive pneumatization in an anteroposterior direction of the sphenoid sinus may lead to thinning in the clival bone during sinus development. 10 Fujii et al proposed that depending on the degree of pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus, clival thickness varies between 0.2 and 10 mm. 11 The posterior wall of a well-pneumatized sphenoid sinus corresponds to the spheno-occipital synchondrosis level in the clival region. 11 These leaks manifest in adulthood and not in childhood. This is explained by the fact that maximum CSF pressure is only attained in an adult (almost three times that of infants), and CSF pressure waves are also higher in adults. 1 4 Additionally, Ramos et al have reported spontaneous CSF fistula through a clival defect in a patient with Marfan syndrome. 12 Connective tissue diseases with altered bone histology may be considered a predisposing factor, though this was not found in any of our cases.

Berdahl et al found a direct linear relationship between ICP and BMI in a series of more than 4,200 patients. 13 BMI was significantly higher in patients with spontaneous CSF leaks when compared with other CSF leak etiologies in the anterior skull base. 14 Four patients in our series had a BMI greater than 30 with defects noted in the posterior skull base. It is proposed that repeated pulsations of the basilar artery may lead to clival erosion. 15 It is hence postulated that repetitive increases in ICPs cause an already thin/weakened skull-base bone in a person with high BMI to give way leading to a dehiscence.

Management of Clival Leaks

Clival leaks are difficult to identify due to the natural posterior slope of the clivus. Clival CSF leaks also tend to drip down into the oral cavity. Leaks from the posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus (upper to mid-clivus) collect within the sinus and form a reservoir causing intermittent bouts of rhinorrhea. Recurrent meningitis (even in the absence of active rhinorrhea) should be met with a high index of suspicion.

Attempts at localization of the skull-base defect are a must prior to operative intervention. HRCT is used as the primary imaging modality to identify the site of the skull base breach and also as a roadmap for surgery. MRI additionally identifies the presence of a meningocele/encephalocele, raised intracranial tension, intracranial tumors, or cortical venous thrombosis. Detailed ophthalmic evaluation including fundoscopy and optical coherence tomography may provide further insight into indirect evidence of raised ICP.

Both intrathecal 16 17 and topical 18 19 use of fluorescein may augment intraoperative identification of a CSF fistula, though intrathecal usage has been associated with rare, but potentially serious complications. Additionally, intraoperative use of intrathecal fluorescein helps identify multiple leaks and confirms a watertight seal following reconstruction. In three of our patients, we used intrathecal fluorescein to identify the leak site intraoperatively.

Management of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

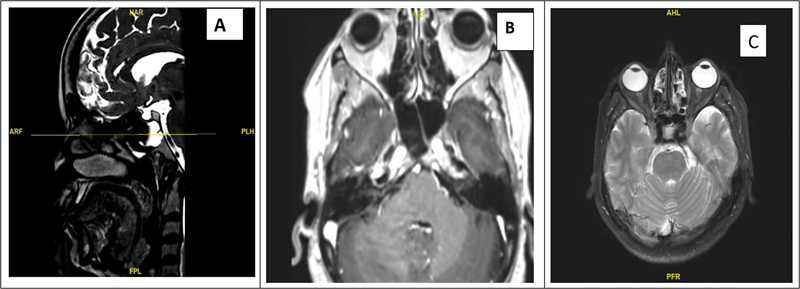

There is substantial evidence to demonstrate increased CSF pressures, with special regards to IIH in patients with spontaneous leaks. Radiographic signs provide indirect evidence of elevated CSF pressures in both IIH and spontaneous CSF leaks. These include empty or partially empty sella, flattening of the posterior globes, tortuosity of the optic nerves, osseous erosion, and widening of skull base foramina and anterior and lateral skull-base attenuation. 20 21 22 Friedman et al recommended that diagnostic guidelines for IIH should include these radiographic characteristics ( Fig. 2 ). 23 These features were noted in three of our cases. Multiple studies have demonstrated direct measurements of CSF pressure in patients with spontaneous CSF leaks. 1 2 24 However, the intrathecal pressure measured at the time of active leak may not be representative of the actual CSF pressure. ICP may be normal during an active leak, because spontaneous CSF leaks may act as a release valve for increased ICPs, thereby normalizing ICPs until after the leak site is repaired. 24

Fig. 2.

( A ) Sagittal CT image depicting bony defect in the mid-clivus and basilar artery posterior to the defect. ( B ) The corresponding axial image on T2-weighted MRI showing communication between subarachnoid space and clival bone with basilar artery posteriorly. ( C ) Axial MRI image showing features of IIH—flattening of globe, optic nerve flaring, and tortuosity. CT, computed tomography; IIH, idiopathic intracranial hypertension; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

A similar finding was observed in one patient whose pre-repair pressure was 13 cm of H 2 O and post-repair was 23 cm of H 2 O. In Case 4, the CSF pressure was in the upper normal range, even though the MRI depicted features of raised ICP. A significant difference in successful repair has been observed in patients who were managed with measures to decrease ICP. The percentage of success rates in patients with active management for elevated CSF was 92.82% and in those without active management of elevated CSF is 81.34%. 25

Common Management Strategies to Control ICP

Strategies to reduce ICP included placement of lumbar drains, and thecoperitoneal (TP) shunt administration of diuretics. Lumbar drains were placed during the perioperative period (in three patients), and TP shunt (in two patients) and diuretics (acetazolamide) were administered in three patients. The common complications of TP shunt include subdural hematoma due to over-drainage, nerve root irritation, paralysis, infection, postspinal headache, pneumocephalus, acquired Chiari malformation, and shunt migration. 7 26 27 28 29 30 Long-term follow-up is deemed necessary for a good outcome in patients with TP shunt.

Anatomical Considerations and Unique Intraoperative Challenges

Reconstruction of a clival defect is challenging in the presence of high CSF pressure, inclination of the clivus, vertical position of the brainstem, limiting the support available for the reconstruction, and proximity to major neurovascular structures 27

The endoscopic transclival approach is limited by the dorsum sellae and posterior clinoids superiorly and the foramen magnum and occipital condyles inferiorly. The lateral boundaries of the surgical corridor are represented on both sides by the paraclival segment of the internal carotid artery and foramen lacerum, the abducens nerve (in the mid-clivus) and the Eustachian tube and the hypoglossal canal (in the lower clivus). 31

It is critical to perform an adequate bone exposure using a diamond drill (bone surfaces bleed profusely) to gain access to the sphenoid sinuses and further expand the cavity to ease the use of instruments deep in the clival recess, being mindful of the vital structures and venous channels behind and inside the bone. This includes the basilar plexus and the confluence of venous sinuses as mentioned previously.

In rare cases where the basilar artery is significantly close to the edges of the defect, an overlay repair needs to be considered. A nasoseptal flap for a vascularized repair is known to have better closure rates. 32 The closure of the leak should be watertight, especially when a lumbar drain/TP shunt is planned to avoid the potential pneumocephalus. Finally, if a nasoseptal flap is being used for closure, care should be taken while drilling the floor of the sphenoid sinus to avoid injury to the vascular pedicle.

Conclusion

Spontaneous clival leaks are a rare entity with the mid-clivus or lower clivus being the common site of the leak. Increased intracranial hypertension is the most common etiological factor. Accurate site leak identification with multi-layered repair reinforced with a vascularized flap and a CSF diversion technique is crucial for a successful outcome.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Beckhardt R N, Setzen M, Carras R. Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104(04):425–432. doi: 10.1177/019459989110400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wise S K, Schlosser R J. Evaluation of spontaneous nasal cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15(01):28–34. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328011bc76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ommaya A K, Di Chiro G, Baldwin M, Pennybacker J B. Non_traumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968;31:214–225. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.31.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shugar J MA, Som P M, Eisman W, Biller H F. Non-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Laryngoscope. 1981;91(01):114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran R S, Behari S, Khatri D, Mathialagan A. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80(05):493–499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatch J L, Schopper H, Boersma I M et al. The bone mineral density of the lateral skull base and its relation to obesity and spontaneous CSF leaks. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(09):e831–e836. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shetty P G, Shroff M M, Fatterpekar G M, Sahani D V, Kirtane M V. A retrospective analysis of spontaneous sphenoid sinus fistula: MR and CT findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(02):337–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooper A C. Sphenoidal defects–a possible cause of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34(06):739–742. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.6.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khairy S, Almubarak A O, Aloraidi A, Alahmadi K OA. Canalis basalis medianus with cerebrospinal fluid leak: rare presentation and literature review. Br J Neurosurg. 2019;33(04):432–433. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2017.1346173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haetinger R G, Navarro J AC, Liberti E A. Basilar expansion of the human sphenoidal sinus: an integrated anatomical and computerized tomography study. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(09):2092–2099. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abuzayed B, Tanriover N, Gazioglu N, Akar Z. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the clival region. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21(01):245–251. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181c5a294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos A, García-Uría J, Ley L, Saucedo G.Transclival cerebrospinal fluid fistula in a patient with Marfan's syndrome Acta Neurochir (Wien) 200714907723–725., discussion 725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berdahl J P, Fleischman D, Zaydlarova J, Stinnett S, Allingham R R, Fautsch M P. Body mass index has a linear relationship with cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(03):1422–1427. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks C A, Palmer J N, Chiu A G, O'Malley B W, Jr, Woodworth B A, Kennedy D W. Endoscopic closure of CSF rhinorrhea: 193 cases over 21 years. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(06):826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coiteiro D, Távora L, Antunes J L. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid fistula through the clivus: report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 1995;37(04):826–828. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199510000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seth R, Rajasekaran K, Benninger M S, Batra P S. The utility of intrathecal fluorescein in cerebrospinal fluid leak repair. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(05):626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Placantonakis D G, Tabaee A, Anand V K, Hiltzik D, Schwartz T H.Safety of low-dose intrathecal fluorescein in endoscopic cranial base surgery Neurosurgery 200761(3, Suppl):161–165., discussion 165–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozturk K, Karabagli H, Bulut S, Egilmez M, Duran M. Is the use of topical fluorescein helpful for management of CSF leakage? Laryngoscope. 2012;122(06):1215–1218. doi: 10.1002/lary.23277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saafan M E, Ragab S M, Albirmawy O A. Topical intranasal fluorescein: the missing partner in algorithms of cerebrospinal fluid fistula detection. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(07):1158–1161. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217532.77298.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidot S, Saindane A M, Peragallo J H, Bruce B B, Newman N J, Biousse V. Brain imaging in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35(04):400–411. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seth R, Rajasekaran K, III, Luong A, Benninger M S, Batra P S. Spontaneous CSF leaks: factors predictive of additional interventions. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(11):2141–2146. doi: 10.1002/lary.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maralani P J, Hassanlou M, Torres C et al. Accuracy of brain imaging in the diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(07):656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman D I, Liu G T, Digre K B. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81(13):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sannareddy R R, Rambabu K, Kumar V E, Gnana R B, Ranjan A. Endoscopic management of CSF rhinorrhea. Neurol India. 2014;62(05):532–539. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.144453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teachey W, Grayson J, Cho D Y, Riley K O, Woodworth B A. Intervention for elevated intracranial pressure improves success rate after repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(09):2011–2016. doi: 10.1002/lary.26612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murtagh F R, Quencer R M, Poole C A. Extracranial complications of cerebrospinal fluid shunt function in childhood hydrocephalus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(04):763–766. doi: 10.2214/ajr.135.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calcaterra T C.Extracranial surgical repair of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 198089(2, Pt 1):108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav Y R, Pande S, Raina V K, Singh M. Lumboperitoneal shunts: review of 409 cases. Neurol India. 2004;52(02):188–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper J R. Migration of ventriculoperitoneal shunt into the chest. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1978;48(01):146–147. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.1.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browd S R, Ragel B T, Gottfried O N, Kestle J RW. Failure of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: part I: obstruction and mechanical failure. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34(02):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aktas U, Yilmazlar S, Ugras N. Anatomical restrictions in the transsphenoidal, transclival approach to the upper clival region: a cadaveric, anatomic study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41(06):457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Rhinologic Society Advisory Board on Endoscopic Techniques in the Management of Nose, Paranasal Sinus and Skull Base Tumours . Lund V J, Stammberger H, Nicolai P et al. European position paper on endoscopic management of tumours of the nose, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Rhinol Suppl. 2010;22:1–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujii K, Chambers S M, Rhoton A L., Jr Neurovascular relationships of the sphenoid sinus. A microsurgical study. J Neurosurg. 1979;50(01):31–39. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.1.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lockwood A H, Quencer R M, Page L K. CSF rhinorrhea from a transclival meningocele demonstrated with metrizamide CT cisternography. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1980;53(04):553–555. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.4.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turanzas F S, Lobato R D, León P G, Gómez P A. CSF rhinorrhea from a transclival meningocele demonstrated by MR. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138(05):595–596. doi: 10.1007/BF01411183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Shurbaji A A, Abu-Salma Z A. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea through clival defect. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2005;10(03):232–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad F U, Sharma B S, Garg A, Chandra P S. Primary spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea through the clivus: possible etiopathology. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(11):1304–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akyuz M, Arslan G, Gurkanlar D, Tuncer R. CSF rhinorrhea from a transclival meningocele: a case report. J Neuroimaging. 2008;18(02):191–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elrahman H A, Malinvaud D, Bonfils N A, Daoud R, Mimoun M, Bonfils P. Endoscopic management of idiopathic spontaneous skull base fistula through the clivus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(03):311–315. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2008.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Zele T, Kitice A, Vellutini E, Balsalobre L, Stamm A. Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks located at the clivus. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2013;4(02):e100–e104. doi: 10.2500/ar.2013.4.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tandon V, Garg K, Suri A, Garg A. Clival defect causing primary spontaneous rhinorrhea. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12(02):328–330. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.144202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanabria-Ortiz R, Domínguez-Báez J, del Toro A, Lazo-Fernández E, Sánchez-Medina Y, Robles-Hidalgo E.Rinorraquia secundaria a meningocele transclival. A propósito de un caso y revisión de la literatura Neurocirugia (Astur) 20152606292–295. 10.1016/j.neucir.2015.02.008[Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi Y, Iwato M, Kita D, Fukui I. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leakage through fistulas at the clivus repaired with endoscopic endonasal approach. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6(01):106. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.158898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pagella F, Pusateri A, Matti Eet al. Endoscopic Management of Spontaneous Clival Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks: Case Series and Literature Review World Neurosurg 201686470–477. 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.026[Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Codina Aroca A, Gras Cabrerizo J R, De Juan Delago M, Massegur Solench H. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid fistula in the clivus. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2017;134(06):431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asad S, Peters-Willke J, Brennan W, Asad S.Clival Defect with Primary CSF Rhinorrhea: A Very Rare Presentation with Challenging Management World Neurosurg 201710610520–1.052E7. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.011[Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karli R, Yildirim U.Endoscopic management of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid fisstula caused by clival defect J Craniofac Surg 20182906e604–e606.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30067524/cited 2020Sep9 [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen G Y, Ma L, Xu M L et al. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: A case report and analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(05):e9758. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nogueira J F, Woodworth B A, Stamm A, Silva M L. A Primary Clival Defect: Endoscopic Binostril Approach With Nasal Septal Flap Closure and Preservation of Septal Integrity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019;98(05):E24–E26. doi: 10.1177/0145561319839507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]