Abstract

Background

TTFields is recommended internationally for the treatment of glioblastoma. In Sweden, TTFields requires a possibly challenging collaboration between the patient, next-of-kin, healthcare, and the private company providing the device, both from an ethical and practical perspective. Little is known about glioblastoma patients’ own experiences of TTFields treatment.

Methods

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with 31 patients with glioblastoma who had been offered TTFields by the healthcare. These were analyzed by qualitative content analysis.

Results

Participants described there being multiple actors around them as TTFields users; (1) device prescription from physicians, sometimes providing insufficient information, (2) practical assistance from next-of-kin, necessary to access treatment, (3) home visits from the private company staff for device control, where close bonds between patients and TTFields staff occurred. TTFields treatment created hope and a feeling of control in an otherwise hopeless situation, sometimes evoking worries at the time of planned treatment stop. Some refrained from TTFields or discontinued early due to fear or experience of negative effects on quality of life. Others described finding practical and mental solutions for coping with the treatment in everyday life.

Conclusions

Our study identified a need for better support and information from healthcare providers for TTFields. A solution is necessary for assistance with TTFields for those without support from next-of-kin. The study raises the question of possible advantages of healthcare handling the technical support of the device instead of a private company, thereby avoiding a true or perceived influence on the patient’s decision to continue or stop treatment.

Keywords: brain tumor, glioblastoma, patient’s perspective, qualitative research, tumor treating fields

Key Points.

Healthcare providers should take more active responsibility for the treatment with TTFields.

A solution for assistance with TTFields is needed for those without next-of-kin.

We raise the option of the healthcare team handling the technical support of the device.

Importance of the Study.

This qualitative interview study points towards the importance of healthcare providers taking more active responsibility for treatment with TTFields, both through adequate and correct information and support during the treatment. Our study found that a close relationship between the patient and company staff sometimes develops based on regular and frequent visits. To avoid a possible influence on the patients to continue with TTFields longer than they desire, this could be achieved by the healthcare team handling the technical support of the device. For equal care, it is essential to find solutions for how patients with glioblastoma without practical help from a next-of-kin can get access to TTFields. Research aiming to also explore the next-of-kin’s and healthcare staff’s experiences of this treatment is needed to add further knowledge and provide information that can facilitate interventions to improve the implementation of TTFields treatment.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary malignant brain tumor in adults and 3-5/100 000 are diagnosed with GBM each year.1,2 A new treatment modality, tumor treating fields (TTFields),2–11 where alternating electric fields are used to treat GBM, was shown to prolong survival by nearly 5 months (from 16.0 to 20.9 months) when added to adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) after standard concomitant radio-chemotherapy with TMZ.8 The treatment has been recommended internationally for GBM2,12 and has since 2018 been approved in Sweden.13,14 TTFields is prescribed by physicians, while the service of equipment and control of its use, which most often occurs in the patients’ home, is performed by staff from a private company providing the device. This staff has no medical responsibility.15 The shaving of the head and placement of the arrays necessitates assistance from another person, usually a next-of-kin.11 This arrangement requires a complex and possibly challenging collaboration between the patient, next-of-kin, the healthcare team, and the company. Furthermore, the treatment is more expensive than most standard treatments.16 Ethical dilemmas, such as availability of the treatment for patients without next-of-kin, the high cost for the healthcare, and the potential influence of the private company on the patients to continue treatment when meeting patients in their homes regularly, are raised. Knowledge is scarce why some patients refrain from TTFields, while others opt for it, why some stopp prematurely, and how patients react to stopping after completing the planned treatment period. Therefore, the aim of this study was to, in a Swedish context, investigate the experiences of TTFields from the perspective of patients with GBM who were offered the treatment.

Methods

Participants and Interviews

Inclusion criteria were: patients with GBM who had been offered TTFields by the prescribing clinician, to understand and speak Swedish, no major cognitive impairment, and to accept that the interview was recorded. Patients who had accepted TTFields, both ongoing and after stopping treatment, and those who had refrained from TTFields were represented. Participants were recruited from multiple oncological and neurological units in Sweden and through advertising the study at the Swedish Brain Tumor Association.

The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr. 2022-02246-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Thirty-one individual interviews were conducted by telephone or at a physical meeting, according to the preferences of the participants. All the interviews were conducted by a researcher (N.L.: female, physician, specialist in oncology and palliative medicine). None of the researchers in the research group (L.K., M.K., N.L., E.D., and A.M.) were involved in the care or treatment of the participants.

An interview guide17 (see Appendix) was constructed by the research group. This interview guide consisted of open questions concerning, for example, information received about TTFields, experiences of treatment for those who had accepted TTFields and reasons for declining or stopping treatment. Also, questions regarding support from the healthcare team and the company providing the device were covered. The interviews were conducted between February 2023 and April 2024 (the duration of the interviews varied between 15 and 55 minutes) and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

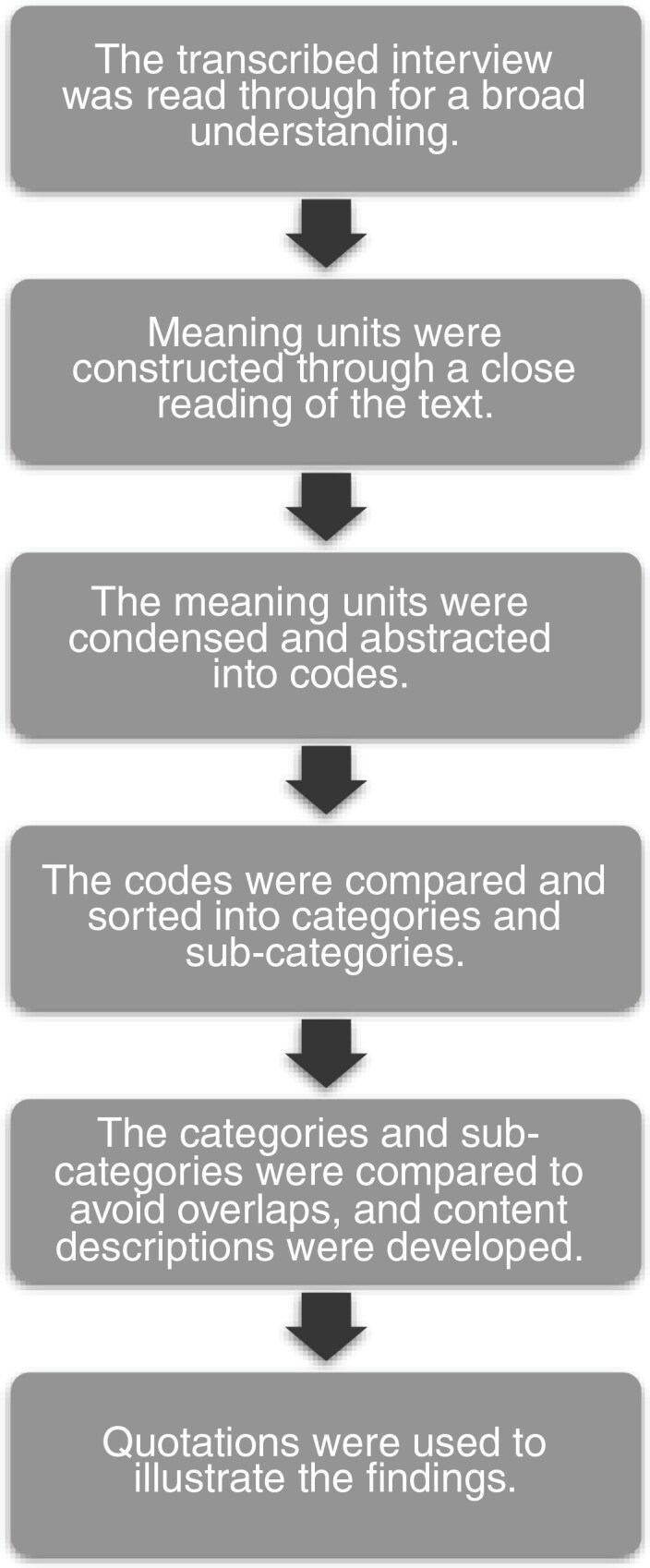

Analysis was made through qualitative content analysis without predetermined categories or themes18 (see Figure 1). The preliminary categories were mainly coded by the first, second, and last authors, who are all physicians (LK: female, general practitioner, MK: female, specialist in geriatrics and palliative medicine, and AM: female, specialist in oncology and palliative medicine) with experiences in qualitative research. The tentative categories were then discussed and revised by all the researchers. As part of the reflexivity process, the categories were validated by supplementing and contesting each other’s readings and preunderstandings.19

Figure 1.

The 6 steps used in the qualitative content analysis.

Results

An overview of the background characteristics of the participants is shown in Table 1. When analyzing the data, 3 categories (with ten sub-categories in total) describing the patients’ experiences of TTFields were identified, namely: Multiple actors around the TTFields user, Impact on daily life and Managing hope and dispair18 (see Figure 2). Examples of the analysis are shown in Table 2. As the study design was according to qualitative methodology using a non-statistical sampling, no information on the exact numbers of different views or perspectives are reported.17

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 31 Participants

| Age mean (range) Age median |

58 years (25–72) 60 years |

|---|---|

| Gender men/women (n [%]) | 18 (58) / 13 (42) |

| Cohabitant/living alone (n [%]) | 24 (77) / 7(23) |

| Accepted TTFields (n [%]) | 27 (87) |

| -ongoing treatment at time of interview (n [%]) | 17 (55) |

| -stopped treatment at time of interview (n [%]) | 10 (32) |

| Declined TTFields (n [%]) | 4 (13) |

Figure 2.

Overview of the 3 categories with ten sub-categories describing the experiences of TTFields from the perspective of patients with glioblastoma who were offered the treatment in a Swedish context.

Table 2.

Examples of the Data Analysis Using Qualitative Content Analysis

| Meaning unit | Code | Sub-category | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| “What I find a bit challenging is that I’m dependent on my partner. He has to assist me, and we need to find a time that works for me to take the breaks. It shouldn’t get too burdensome for him. // So that’s really what I find most difficult – being unable to manage the treatment on my own.” | Challenging to be dependent on next-of-kin. Dependent on next-of-kin for practical help. |

Dependency on practical help | Multiple actors around the TTFields user |

| “We’ve been to the swimming pool and such things, and it doesn’t really work there. // But then during the winter break, we went skiing … // and that backpack worked perfectly well. The arrays fitted under the helmet when we were skiing downhill, so it worked out fine.” | Swimming not possible when using TTFields. Skiing possible when using TTFields. TTFields when being physically active. |

Planning life around TTFields | Impact on daily life |

| ”Yes, but you see, I have a grade four, so I’ll take all the help I can get. I’m going to fight against this, I’m going to win.” | Taking all the help one can get. Fighting against the disease. Hoping for TTFields to have positive effect. |

TTFields creating hope | Managing hope and dispair |

Multiple Actors Around the TTFields User

Varying support from the healthcare team.—

Participants could have received information about TTFields at different time points from diagnosis and during treatment. The timing of information about the option of treatment with TTFields was essential, and the patient needed enough time to make a decision.

Well, I remember, and what felt strange to me was . . . that I received that information [on TTFields] after having received the (cancer)information, and I wasn’t receptive to it. (P30, female, accepted TTFields).

… He presented that there was a new treatment method that he wanted me to use, and he wanted an immediate response regarding whether I accepted the offer or not. I felt quite pressured. (P21, male, accepted TTFields)

The patient’s own knowledge of TTFields was described as scarce and the views regarding the sufficiency and accuracy of the healthcare staff’s information about TTFields varied. Some experienced that the amount and quality of information was enough to make a decision, while others found it insufficient and sometimes incorrect.

… He [the physician] explained various studies that existed, as well as ideas and thoughts behind it, how it worked. He provided a very detailed explanation of how it works, both technically and in terms of how long one should use it. He also referenced studies from Germany, I believe, where people had already been using it [TTFields] … (P19, male, accepted TTFields)

… I think they described it somewhat inaccurately, saying that one should wear electric plates on the head. And then, I envisioned some kind of helmet, something quite bulky. We received a brochure that was a copy of something … from a small folder, and it was very dark, making it difficult to discern what it was. There was a photo of a person, and it was difficult to see what the person was wearing on her head // It was also described as to be worn for 18 hours and then having time off, in a way. But that’s not quite accurate. So, the image that I got of Optune [TTFields] when I received the offer doesn’t align at all with how I personally experience using it. (P16, female, accepted TTFields)

Some were content with the support from healthcare staff when having any medical issues related to TTFields. Others viewed that the general knowledge about TTFields among healthcare staff from the prescribing clinic was poor and that the healthcare team tended to refer to the company responsible for the device even if the questions concerned pure medical matters.

Easy access to the company.—

Support, commitment, and availability by the company staff were perceived as generous. Apart from the regular visits to the user’s home, the contact person was available for any questions and responded quickly regarding the device and for service of equipment. Questions on medical issues were referred to healthcare staff.

No, she [the contact person at the company] sent a new one to me // It arrived … the same day, on a Saturday. // Yes. It was very promptly arranged, and she has been very competent and accommodating. (P8, female, accepted TTFields)

Based on a regular visit to the user’s home, sometimes for a long time, some experienced that a friendship evolved and that this relationship gave support and safety during the course of disease.

No, but certainly, she … she became more like a friend than an Optune [TTFields] … // Yes, she has that way. // It ended up feeling more like an acquaintance. So, if it was tough, it was tough, and that was the way it was, and we let it be tough in that moment. (P2, male, accepted TTFields)

However, for a few, the perceived “salesy approach” of the private company was viewed as somewhat distasteful.

In our situation as glioblastoma patients, we don’t want to hear sales pitches. We don’t want that. We seek comfort. We desire.... Our clock is truly ticking. (P26, male, accepted TTFields)

None of the participants had continued the treatment when healthcare professionals had recommended discontinuing it.

Dependency on practical help.—

Different perspectives of the need of support from others were described. For some, being dependent on their next-of-kin, was associated with discomfort.

What I find a bit challenging is that I’m dependent on my partner. He has to assist me, and we need to find a time that works for me to take the breaks. It shouldn’t get too burdensome for him. // So that’s really what I find most difficult – being unable to manage the treatment on my own. (P16, female, accepted TTFields)

For others, being dependent was not an issue. Instead, their gratitude was expressed towards their families who could help and enable the treatment with TTFields.

I don’t feel dependent at all; quite the opposite, I feel immense gratitude. So, I think, if someone doesn’t have anyone, what do they do? Well, then they must go somewhere or find someone who can come home and take care of things. But for me it’s fantastic … (P17, female, accepted TTFields)

When living alone, support from the healthcare team was a necessity for the daily use of the device as this practical support could not be given by a next-of-kin.

So, what I would like to say about this is that if you have patients with the same condition as mine, and they are offered treatment, it’s essential to also arrange assistance for patients whose life circumstance is that they live alone, so that one gets help. (P18, female, accepted TTFields) (P10, male, declined TTFields)

Facilitating strategies.—

Strategies to cope with difficulties and disadvantages caused by the treatment were described. These strategies were own ideas, or suggestions by the company offering the device, or medical advice from the healthcare team. Then there were other users, in online patient communities, who provided their own ideas and gave tips and advice on how to make life with TTFields easier.

Yes, I got a tip about that little cap from a woman who had used Optune [TTFields] before me, because she had sat in the sun wearing this cap. And then, when I looked into that company, I also found this scarf that had cooling elements, so I had both. But mostly, I wore a hat, a wide-brimmed straw hat in the summer, and it was great! (P18, female, accepted TTFields)

Impact on Daily Life

Planning life around TTFields.—

Some described the fear of making the disease visible, not only for the user him- or herself but also for others. This was for some, a crucial obstacle to agreeing to the treatment.

I felt ill. I needed to have something physical on me. So, in a way, it makes you feel sick... (P26, male, accepted TTFields)

… It’s a significant step to take, this one, if you’re going into it. You have to go somewhere, and then you have to shave your head completely. And then, when you have that attached, every person you encounter will ask what it is when you go out, of course. (P10, male, declined TTFields)

For some participants who were users, developing routines for TTFields facilitated daily life and made it possible to continue with activities and they made plans for doing some activities mainly when taking a break from treatment.

… I decided from the beginning, I switch on Wednesdays and Saturdays. // … We have an old tradition of golfing with good friends on Wednesdays, and then we have lunch afterward. So, I’ve been able to continue with that, without needing the device during those hours. (P17, female, accepted TTFields)

Some underlined that treatment with TTFields was not hindering them from doing sports, such as skiing, while other activities were not possible.

… We’ve been to the swimming pool and such things, and it doesn’t really work there. // But then during the winter break, we went skiing … // and that backpack worked perfectly well. The arrays fitted under the helmet when we were skiing downhill, so it worked out fine. (P14, male, accepted TTFields)

Coping with side effects and discomfort.—

The device was described as heavy and uncomfortable, and some had suggested ways for improvement to the company providing it. However, users who lived active lives meant that they got used to it over time.

… the device is quite large. And the bag must go everywhere. And I do a lot. I am very active. I took it to work, to restaurants, and to the theater, you know, like that. // ….. And it wasn’t so fun, but you got used to it anyway. (P25, female, accepted TTFields)

There were varying extents of skin irritation, such as rash and ulceration and sometimes skin infections. Usage of moisturizer and mild cortisone cream or shifting the position of the arrays was sometimes enough. In some cases, recurring ulcers were a reason to stop the treatment.

… my contact person at X [the private company], she said many times that ‘you must take a break.’ And I didn’t do it because I’m stubborn and all that, and of course, it got even worse. And I needed breaks. And eventually, it becomes unsustainable. Partly because I needed so many breaks, but also because it didn’t work. It was difficult to find areas on the scalp where there were no sores. (P25, female, accepted TTFields)

Quality of life surpasses everything.—

For some, preserved quality of life (QoL) was the most important aspect and although having the knowledge that there was a chance that treatment with TTFields could prolong life, impaired QoL caused by the treatment was a fear for some and a fact for others, influencing their decision regarding TTFields.

No, but I said yes to everything in the beginning too, because you were supposed to be … But then when you found out how long you were supposed to use that device and all … // It’s probably the lifestyle. And then there’s the fact that it’s 18 hours a day. It’s all waking time. (P29, male, declined TTFields)

But I can understand that people want to use it, but at the same time, I felt sicker, and I don’t know if it has had any effect on me. // … you have to use it so much for it to have any effect, and it won’t save your life. So, it’s quite burdensome for gaining three to five months. That’s really the summary of how I feel. (P26, male, discontinued TTFields)

I just feel that, perhaps unfortunately, but this was the right decision for me, that … Now when I wake up in the morning, I feel relieved that I quit those arrays. (P28, male, discontinued TTFields)

Managing Hope and Dispair

TTFields creating hope.—

Some expressed that when getting the opportunity with TTFields, one could not refrain, since it could prolong one’s life. According to participants who accepted TTFields, the treatment created hope when suffering from a life-threatening illness.

Yes, but you see, I have a grade four, so I’ll take all the help I can get. I’m going to fight against this, I’m going to win. (P22, female, accepted TTFields)

Accepting TTFields meant for some to gain control and this contributed to a feeling of actually doing something oneself to counteract the tumor rather than passively waiting.

… the feeling that you do something … you do something against this rascal. It’s not just lying down and waiting. (P2, male, accepted TTFields)

Doubt and uncertainty about the effect.—

For a few, the treatment could instill false hope, knowing that they were approaching death and without a chance of a cure.

But at the same time, I’m ambivalent about this because this is … It’s nothing that will save my life, I’ve understood that. It would have been gratifying if it were so, but it’s not … (P26, male, accepted TTFields)

One reason to refrain from TTFields treatment was uncertainty about the treatment effect and if the benefit would outweigh the discomfort.

… If it had been like this, that you take this test and receive … information that ‘if you have it for three months, then you’ll be completely cured’ … // Well, then it wouldn’t have been a problem to do it. // Now … now it’s about a certain percentage that, yes, might improve over a slightly longer period. (P10, male, declined TTFields)

Stopping treatment arouses fear.—

Treatment with TTFields could be associated with feelings of safety and security, according to the participants who had accepted it. Therefore, approaching the day of the planned 2 years treatment, not only led to a feeling of relief but also arouse fears of what would happen after stopping the treatment.

… As it got closer and closer, it was kind of like ‘sure, it’s nice to get rid of it’, but still, it provided a … It felt like it gave a sense of security or comfort, so it was a bit difficult leading up to it. (P7, female, accepted TTFields)

Discussion

TTFieds is a relatively new treatment modality, which can be viewed as challenging in several ways. While offering the patients a chance for substantial survival benefits, it could also be stigmatized by the need to shave the head and by making the equipment visible to others, constantly reminding the user of the disease. Dependency on practical help from others and the collaboration of the private company´s staff directly with the patients and families are other challenges. The role of the company could potentially lead to less involvement from the healthcare team. For some participants close bonds developed with the company´s staff.

In this study, we interviewed thirty-one patients with GBM who were offered TTFields. Four had declined the treatment. Some of those who started stopped early, due to side effects or QoL issues. While most patients appreciated the visits and assistance from the company´s staff in their homes, the experiences regarding the commitment from the healthcare team concerning TTFields varied. This could indicate a need for healthcare staff to take more responsibility for this treatment as is standard for other anticancer treatments.

Some participants expressed that when getting the opportunity with TTFields, one could not refrain, as the treatment could give hope to prolong one’s life. The importance of hope for patients with cancer at all stages of the disease is well documented.20–23 Previous research has shown a complex relationship between patients’ knowing the reality of their situation and poor prognosis and hoping for a treatment that would have a positive effect. Therefore, “trying everything” could be a way of maintaining hope.24,25

Taphoorn et al. showed that Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) did not differ significantly among patients with TTFields and TMZ compared to those with only TMZ.26 In some participants in our study, TTFields effected users’ QoL negatively, while others successfully integrated treatment into their daily lives. Treatment with TTFields enables the patient to participate more actively in his or her own treatment in contrast to most other cancer treatments.15 Some participants viewed that TTFields was associated with patient empowerment contributing to a feeling of actively participating in their cancer treatment, rather than passively waiting. This active involvement in the treatment could strengthen the patient’s hope through increased own control, a correlation which has been previously shown.20

In this study, different perspectives of the users’ need for support from others are viewed. For some participants, being dependent on their next of kin was associated with discomfort. The association between GBM patients and their dependency on their next-of-kin27,28 and their family members’ experiences of stress and burden29–33 are previously documented. Besides the impact of the disease itself, treatment with TTFields affects not only the patients but also the families, in their daily lives, which could contribute to additional burden and feelings of guilt.

Today, healthcare provides varying information regarding TTFields. To achieve equal care, ensuring adequate information and support for both patients and their families regarding the treatment is a key element, where standardized information on TTFields could be a feasible option. Also, as this treatment necessitates assistance from another person, a solution needs to be found for patients who are eligible for treatment, but where the patient lives alone or where next-of-kin, for various reasons, are unable to assist.

The private company being closely involved with patients and their families in their homes might give rise to different ethical problems. This role of the company could potentially lead to less involvement of the healthcare team in this tumor-specific therapy, as experienced by some patients. Our study found that a close relationship between the patient and company staff sometimes develops based on regular and frequent visits. While the patients report this mainly to be appreciated, a disadvantage could be a possible influence on the patients to continue with treatment even when having doubts or diminished QoL, of fear of losing a supportive relationship. A longer treatment than desired is problematic, as TTFields is costly. It is reimbursed by the healthcare, which is in need of prioritizing the use of limited resources. To avoid the risk of any inappropriate influence, it could be more reasonable for the healthcare team to handle the technical support of the device. This is the case for most other technical devices used in a patient’s home, such as oxygen concentrators and ventilators. This could also lead to improved involvement of healthcare staff in TTFields treatment as it would clarify that it is solely the healthcare team’s responsibility.

Strengths and Limitations

The broad variation of participants (in terms of age, gender, time since GBM diagnosis to interview, family situation, education/occupation, type and location of the clinic responsible for the patient’s treatment and duration of TTFields treatment and participants who had both accepted and declined treatment) supports the transferability of the findings.17 Involvement of researchers with experience in qualitative research and from different disciplines (oncology, palliative medicine, and primary care), as well as lived experience from the Swedish Brain Tumor Association, provided an opportunity to validate the findings.19 The researcher who conducted the interviews is an oncologist, which could have influenced the answers of the participants. However, the interviewer tried to remain neutral throughout the study process and was not involved in the treatment or care of the participants. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)34 were used for reporting the results, strengthening the trustworthiness of our study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems important that healthcare providers take more active responsibility for the treatment with TTFields, as is the case with other tumor treatments. This includes both explaining the terms of the treatment through adequate and correct information, clarifying what is to be expected from the patients and their next-of-kin, and offering both medical and psychological support during the treatment. Further research is needed in order to facilitate and improve the patient’s experiences of the treatment. To achieve equal care, it is essential to find solutions for how patients with GBM who are lacking practical help from a next-of-kin can get access to TTFields. We suggest the healthcare’s medical-technical support organization to handle the support for TTFields as well, to minimize true or perceived influence from the private company staff on the patient’s decision to continue or stop treatment. Last, research aiming to also explore the next-of-kin’s and healthcare staff’s experiences of TTFields is needed and is ongoing. This will add further knowledge and is expected to provide information that can facilitate interventions to improve the implementation of treatment with TTFields.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at Neuro-Oncology Practice (https://academic.oup.com/nop/).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating patients in this study and the clinics and the Swedish Brain Tumor Association for help with recruiting the participants. We also thank Linköping University, Region Östergötland and the Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden.

Contributor Information

Lisa Kastbom, Primary Health Care Centre Ekholmen, Linköping and Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

Marit Karlsson, Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; Department of Advanced Home Care in Linköping and Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

Nina Letter, Department of Advanced Home Care in Linköping and Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

Eskil Degsell, Swedish Brain Tumor Association and NOCRiiC, Neuro Oncology Clinical Research, innovation, implementation and Collaboration, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and Department of Micro, Tumor and Cell biology (MTC), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Annika Malmström, Division of Cell and Neurobiology, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; Department of Advanced Home Care in Linköping and Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden (Dnr. FORSS-976715, 981775, 995108) and a grant from the Swedish Brain Tumor Association.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Authorship statement

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Data collection through individual interviews was performed by Nina Letter. During the analysis, the preliminary categories were mainly coded by the Lisa Kastbom, Marit Karlsson and Annika Malmström. The tentative categories were then discussed and revised by all the researchers. The first draft of the manuscript was mainly written by Lisa Kastbom and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available on request from the authors.

References

- 1. McKinnon C, Nandhabalan M, Murray SA, Plaha P.. Glioblastoma:clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan AC, Ashley DM, López GY, et al. Management of glioblastoma: State of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballo MT, Conlon P, Lavy-Shahaf G, et al. Association of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy with survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol. 2023;164(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ghiaseddin AP, Shin D, Melnick K, Tran DD.. Tumor treating fields in the management of patients with malignant gliomas. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(9):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller R, Niazi M, Russial O, Poiset S, Shi W.. Tumor treating fields with radiation for glioblastoma: A narrative review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2022;11(5):40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moser JC, Salvador E, Deniz K, et al. The mechanisms of action of tumor treating fields. Cancer Res. 2022;82(20):3650–3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rick J, Chandra A, Aghi MK.. Tumor treating fields: A new approach to glioblastoma therapy. J Neurooncol. 2018;137(3):447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas AA, Rauschkolb PK.. Tumor treating fields for glioblastoma: Should it or will it ever be adopted? Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(6):857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wenger C, Miranda PC, Salvador R, et al. A review on Tumor-Treating Fields (TTFields): Clinical implications inferred from computational modeling. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2018;11:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burri SH, Gondi V, Brown PD, Mehta MP.. The evolving role of tumor treating fields in managing glioblastoma: Guide for oncologists. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(2):191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, et al. Glioblastoma in adults: A Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(8):1073–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Det medicintekniska produktrådet (MTP-rådet). Optune för behandling av glioblastom. Rekommendation; 2022. 8 Jun. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Regionala cancercentrum i samverkan. Tumörer i hjärna, ryggmärg och dess hinnor. Nationellt vårdprogram. Version 4.0; 2023. 29 Aug. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy J, Bowers ME, Barron L.. Optune®: Practical Nursing Applications. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(5 suppl):S14–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tandvårds- och Läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV). Hälsoekonomisk utvärdering av Optune. 2017. Contract No.: Report no. 988/2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: California, SAGE Publications, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graneheim UH, Lundman B.. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malterud K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang LC, Li IC.. The correlation between perceptions of control and hope status in home-based cancer patients. J Nurs Res. 2002;10(1):73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill DL, Boyden JY, Feudtner C.. Hope in the context of life-threatening illness and the end of life. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023;49:101513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nierop-van Baalen C, Grypdonck M, van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S.. Hope dies last … A qualitative study into the meaning of hope for people with cancer in the palliative phase. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(4):570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nierop-van Baalen C, Grypdonck M, van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S.. Health professionals’ dealing with hope in palliative patients with cancer, an explorative qualitative research. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(1):e12889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moore SA. need to try everything: Patient participation in phase I trials. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(6):738–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Oosterhout SPC, Ermers DJM, Ploos van Amstel FK, et al. Experiences of bereaved family caregivers with shared decision making in palliative cancer treatment: A qualitative interview study. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taphoorn MJB, Dirven L, Kanner AA, et al. Influence of treatment with tumor-treating fields on health-related quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(4):495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taillibert S, Laigle-Donadey F, Sanson M.. Palliative care in patients with primary brain tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(6):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taphoorn MJ, Klein M.. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boele FW, Weimer J, Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, et al. The added value of family caregivers’ level of mastery in predicting survival of glioblastoma patients: A validation study. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(5):363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, et al. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients--observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(12):1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McConigley R, Halkett G, Lobb E, Nowak A.. Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: a time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sherwood P, Given B, Given C, et al. Caregivers of persons with a brain tumor: A conceptual model. Nurs Inq. 2004;11(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ståhl P, Henoch I, Smits A, Rydenhag B, Ozanne A.. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma and their relatives. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022;146(1):82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.