Abstract

Background and Aims:

For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome, bariatric procedures such as vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) have a clear benefit in ameliorating metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). While the effects of bariatric surgeries have been mainly attributed to nutrient restriction and malabsorption, whether immuno-modulatory mechanisms are involved remains unclear.

Approach and Result:

Using murine models, we report that VSG ameliorates MASH progression in a weight loss-independent manner. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that hepatic lipid-associated macrophages (LAMs) expressing the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) repress inflammation and increase their lysosomal activity in response to VSG. Remarkably, TREM2 deficiency in mice ablates the reparative effects of VSG, suggesting that TREM2 is required for MASH resolution. Mechanistically, TREM2 prevents the inflammatory activation of macrophages and is required for their efferocytic function.

Conclusions:

Overall, our findings indicate that bariatric surgery improves MASH through a reparative process driven by TREM2+ macrophages, providing insights into the mechanisms of disease reversal that may result in new therapies and improved surgical interventions.

Keywords: inflammation, lipid-associated macrophages, NASH, scRNA-seq, vertical sleeve gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is estimated to affect 30% of the population and is one of the leading causes of abnormal liver function.1 MASLD covers a wide spectrum of liver pathology ranging from simple lipid accumulation to the more serious metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH), characterized by inflammation, hepatocellular injury, and fibrosis.2 Hepatic inflammation is primarily driven by liver macrophages and is a critical component in the initiation and progression of MASH.3 Bariatric procedures such as vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) are the most successful and effective treatment options for obese adults and are effective at ameliorating the progression of MASH.4,5 While changes in body weight have a profound metabolic impact, bariatric surgery often results in improved insulin sensitivity before any substantial weight loss, indicative of weight-loss–independent effects.6 Several mechanisms of weight-loss–independent improvements in metabolism due to bariatric surgery have been proposed in mice and humans, including gut hormones,7 intestinal tissue reprogramming,8 changes in the gut microbiome,9 and iron absorption.10 However, whether bariatric surgery ameliorates the progression of MASH through immunomodulatory mechanisms has not been investigated.

MASH is associated with the emergence of macrophages with a unique lipid handling signature, termed hepatic lipid-associated macrophages (LAMs), that express the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2).11 Hepatic LAMs correlate with disease severity, preferentially localize to steatotic regions, and are highly responsive to dietary intervention.12,13 In murine MASH, TREM2 is required for effective efferocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes.14 However, prolonged hypernutrition and hepatic inflammation promote the shedding of TREM2 from the cell surface of macrophages, leading to ineffective clearance of dying hepatocytes.14 Such cleavage of TREM2 increases soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) in the circulation, making it a promising biomarker of disease severity.15 TREM2 is also required for adequate metabolic coordination between macrophages and hepatocytes, lipid handling, and extracellular matrix remodeling.14–16 In a mouse model of hepatotoxic injury, TREM2 deficiency exacerbated inflammation-associated injury through enhanced toll-like receptor signaling, suggesting a key anti-inflammatory function.17 As TREM2 is a central signaling hub regulating macrophage function, therapeutic efforts have been made to stimulate the TREM2 active domain or block its shedding in neurodegenerative18 and cardiovascular19 diseases. However, despite the evidence suggesting that TREM2+ macrophages are protective against MASH, the mechanisms underlying their restorative function are poorly understood.

In the current study, we found that VSG ameliorates the progression of MASH and results in profound effects on the hepatic macrophage transcriptomic profile in a weight-loss–independent manner. Remarkably, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) revealed that the hepatic LAMs upregulate their anti-inflammatory and efferocytic programs in response to bariatric surgery. Most notably, TREM2 deficiency prevented VSG-induced MASH reversal, suggesting that TREM2 is essential for the beneficial effects of bariatric surgery in the liver. Mechanistically, TREM2 prevents the production of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages and is required for adequate efferocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes. Overall, our results indicate that bariatric surgery improves MASH through a reparative process driven by TREM2+ macrophages.

METHODS

Animals

Five-week-old C57BL/6J (000664) and TREM2-deficient (TREM2 knockout [KO]; C57BL6/J background, 027197) male mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. At 6 weeks of age, grouped-house mice were fed a high-fat high-carbohydrate (HFHC, 40% kcal palm oil, 20% kcal fructose, and 2% cholesterol supplemented with 23.1 g/L d-fructose and 18.9 g/L d-glucose in the drinking water).20 Mice were fed the HFHC diet for an average of 14 weeks and then assigned to either a sham operation or VSG surgery. To account for weight-loss–independent effects, we included a sham ad-libitum-fed group (Sham AL) and a sham group that was pair-fed (Sham PF) to the VSG group to match the weight loss after surgery. We also included a group of mice fed a normal chow diet (NCD) for the duration of the study. Additional details are found in the Supplemental Information, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

scRNA-seq

Two million F4/80+ cells from each sample were individually labeled with cell multiplexing oligos (10X Genomics) for multiplexing and sequenced in a Novaseq S4 chip (2 × 150 bp PE). Analyses were performed using Seurat, and visualization of clusters was enabled using uniform manifold approximation and projection. Additional details are found in the Supplemental Information, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682.

Spatial transcriptomics

Fixed mouse liver sections were mounted and stained with DAPI and an anti-CD68 to create macrophage-free regions of interest (ROIs). Human liver sections were stained with DAPI, anti-CD68, and anti-panCK antibodies for ROI segmentation. Spatial sequencing was performed using the GeoMx platform (NanoString).21 Additional details are found in the Supplemental Information, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682.

Human specimens

Human deidentified specimens were previously collected by the Biological Materials Procurement Network (BioNet) at the University of Minnesota. We used specimens collected by liver biopsy from 1 patient before and 1 year after VSG and from a patient diagnosed with MASH without any surgical intervention (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Samples were obtained with institutional review board approval.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism (version 10.0.2). All data analyzed by ANOVA followed a Gaussian distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) and had equal variances (Brown-Forsythe). For data sets that failed the normality test, statistical significance was determined using multiple nonparametric 2-sided Mann-Whitney tests. Mouse studies were repeated in at least 2 independent experiments. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

RESULTS

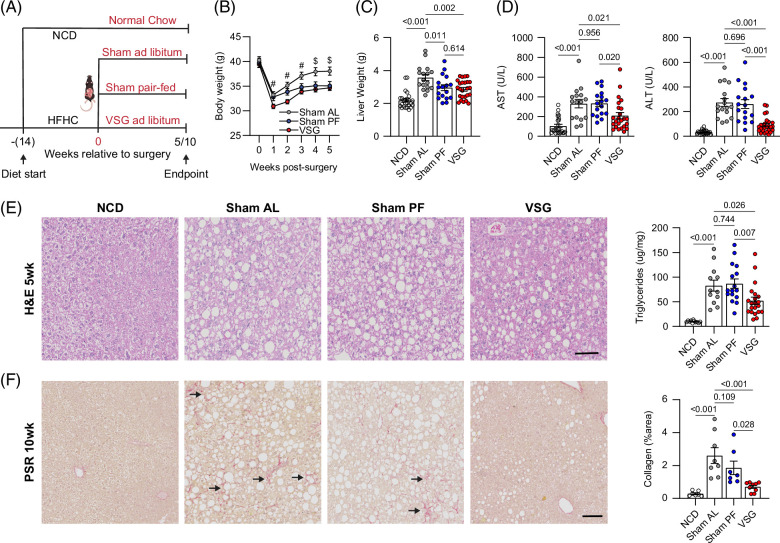

VSG ameliorates MASH progression independent of weight loss

To determine the mechanisms by which bariatric surgery ameliorates MASH, we used a validated mouse model of VSG in which ~80% of the lateral stomach of mice is clamped by a gastric clip and excised.9 Mice were fed the HFHC diet ad libitum for 14 weeks and then assigned to either sham (Sham AL) or VSG surgery and remained on the HFHC diet for an additional 5 or 10 weeks (Figure 1A). To determine the weight-loss–independent effects, we included a sham group that was pair-fed to the VSG group (Sham PF) to match their caloric intake during the postsurgery period.22 In addition, a group of mice were fed an NCD for the duration of the studies. Compared with Sham AL, both VSG and Sham PF mice had a similar decrease in daily food intake (Supplemental Figure S1A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Body weight rapidly decreased in all groups following the surgeries (Figure 1B). However, while the body weight in Sham AL mice recovered, Sham PF and VSG mice maintained their weight loss (Figure 1B). Five weeks after the surgeries, both Sham PF and VSG caused a similar decrease in liver weight (Figure 1C). Nevertheless, only the VSG group showed a reduction in ALT/AST (Figure 1D) and hepatic lipid accumulation (Figure 1E), suggesting that the effects of VSG on these parameters of MASH are independent of the reduced caloric intake induced by the surgery. Ten weeks after the surgeries, the differences in body and liver weight among groups were less evident (Supplemental Figure S1B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), but the VSG-induced reductions in liver ALT (Supplemental Figure S1C, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682) and triglycerides (Supplemental Figure S1D, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682) persisted at this later time point. There was a minimal accumulation of collagen in all groups at the 5-week time point (Supplemental Figure S1E, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), although the expression of fibrosis genes was already diminished in VSG and Sham PF mice (Supplemental Figure S1F, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). As fibrosis developed, VSG mice showed a lower collagen deposition than Sham AL and PF controls at the 10-week time point (Figure 1F). Overall, these findings show that VSG results in a substantial amelioration of several aspects of MASH progression in a weight-loss–independent manner.

FIGURE 1.

VSG ameliorates MASH progression independent of weight loss. (A) Experimental design, (B) weekly body weights after surgery (# p < 0.05 for VSG vs. Sham AL, $ p < 0.05 for VSG vs. Sham AL and VSG vs. Sham PF comparisons), (C) liver weight, (D) serum AST (left) and ALT (right), (E) representative H&E-stained liver sections (left) and hepatic triglyceride content (right) in C57BL6/J (WT) mice fed an HFHC diet for 14 weeks before assignment to Sham AL (n = 6–17), Sham PF (n = 6–17), or VSG (n = 6–25) surgeries. Mice were maintained on the HFHC diet for 5 weeks after surgery. A cohort of mice without any intervention were fed an NCD (n = 8–25) throughout the study. (F) Representative Picro Sirius Red–stained liver sections (left) and collagen area (right) 10 weeks after surgery; NCD (n = 8), Sham AL (n = 8), Sham PF (n = 7), and VSG (n = 9). Arrows identify regions with collagen deposition. Data are biological experimental units presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Holm-Šídák multiple comparison test. Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HFHC, high-fat high-carbohydrate; MASH, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis; NCD, normal chow diet; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; Sham PF, Sham pair-fed; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy; WT, wild type.

To determine if the VSG-induced improvements in MASH were associated with alterations in the gut microbiota and its metabolites, we analyzed the fecal microbial composition of NCD, Sham AL, Sham PF, and VSG mice 5 weeks after surgeries. Compared with NCD mice, HFHC feeding induced a dramatic remodeling in gut microbial species, including increased abundances of Akkermansia, Erysipelotrichaceae, Parasutterella, Ruminococceae, Clostridium XVIII, and decreased abundances of Lactobacillus, and Alistipes (Supplemental Figure S1G, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682 and Supplemental Data File S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I683). While HFHC feeding caused a substantial loss of Lactobacillus, regardless of surgical treatment, VSG resulted in a restoration of this genus toward levels found in NCD mice (Supplemental Figure S1H, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). In contrast, the HFHC diet increased the abundance of Clostridium XVIII, whereas it was partially lowered following VSG (Supplemental Figure S1H, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). We also measured the concentrations of bile acids (BAs) and short-chain fatty acids in the portal vein blood. While HFHC feeding increased the total amount of BA, as observed in Sham AL mice, both Sham PF and VSG mice had decreased BA concentrations to levels similar to NCD controls (Supplemental Figure S1I, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682 and Supplemental Data File S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I684). HFHC feeding also decreased the concentration of short-chain fatty acids in hepatic portal serum and neither VSG nor Sham PF had an impact on their concentration (Supplemental Figure S1J, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682 and Supplemental Data File S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I685). We measured fecal lipids to estimate intestinal lipid absorption and confirmed that VSG mice had decreased intestinal lipid absorption compared with Sham AL mice (Supplemental Figure S1K, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Overall, these data suggest that the VSG-induced improvements in MASH are associated with a partial restoration of specific gut microbial species and BAs.

scRNA-seq reveals profound effects of VSG on hepatic LAMs

To explore the impact of VSG on hepatic macrophages, we used droplet-based scRNA-seq to profile the gene expression of magnetically sorted F4/80+ cells from the livers of Sham AL, Sham PF, and VSG mice (Figure 2A). We multiplexed samples using cell multiplexing oligos to track the origin sample and remove multiplets (Supplemental Figure S2A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). We profiled the gene expression of 58,904 single cells (50,000 avg. read depth; 8204 avg. counts/cell; and 17.2% mitochondrial/ribosomal genes, Figure 2B). Independent of surgical groups, we discerned 18 clusters of monocytes and macrophages, whose identity was determined based on the expression of established marker genes11,20 (Figure 2C, Supplemental Figure S2B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682, and Supplemental Data File S4, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I686). Clusters 0, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13, and 16 were identified as monocyte-like cells, while clusters 1, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 14 were macrophages (Figure 2C). Monocyte clusters had heterogeneous gene expression profiles indicative of their progressive stages of maturation and function. Clusters 0, 2, and 7 had dual monocyte and macrophage features, such as Ly6c2 and H2-Ab1, suggesting they were transitioning monocytes. Cells in cluster 6 were identified as classical monocytes based on their high expression of Ly6c2 and Ccr2. Monocytes in cluster 8 were enriched in Spn and did not express Ccr2 and Ly6c2, indicating they were nonclassical patrolling monocytes. Clusters 13 and 16 corresponded to unidentifiable monocyte populations that expressed high levels of Il2rb and Cxcr2, respectively (Figure 2C). Macrophage subsets were broadly divided into KCs and monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMFs). Clusters 3, 9, and 10 were identified as KCs (KC1–3) based on their expression of Clec1b, Clec4f, Vsig4, and Folr2. These clusters of KCs had a minimal expression of Timd4, suggesting that they are primarily monocyte-derived KCs.23 Clusters 3 and 9 had a similar gene expression pattern, although cluster 3 was enriched in genes associated with efferocytosis, such as Mertk and Wdfy3. Cluster 10 was enriched in Esam and Cd36 and resembles a recently identified subset of pathogenic KCs termed “KC2.”24 Among MoMFs, cells in cluster 1 were enriched for LAM genes, including Trem2, Spp1, Lipa, C3ar1, and Cd36 25 (Figures 2C, D and Supplemental Data File S4, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I686). Pathway analysis showed that LAMs have enriched gene programs associated with lipid metabolism, such as “Lipoprotein particle binding” and “Lipase activity” (Figure 2E). Cluster 4 was composed of MoMFs and transitioning monocytes that could not be further characterized based on their differential gene expression. Cells in cluster 14 were enriched in hemoglobin genes Hba-a1 and Hba-a2, which are highly expressed by erythrophages. Cluster 12 had a high G2M score and was enriched with Top2a, typical of proliferating macrophages (Figures 2C, D and Supplemental Data File S4, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I686). To gain insight into the differentiation of macrophage subsets, we performed a slingshot trajectory analysis of our integrated data set. Using monocytes as the origin, we found 3 primary trajectories by which newly recruited monocytes differentiate into transitioning monocytes and then either differentiate into LAMs, KC1s, or Trans Mon2s (Figure 2F and Supplemental Figure S2C, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). These data suggest that LAMs are derived from classical monocytes and are consistent with recent scRNA-seq studies.11

FIGURE 2.

scRNA-seq shows a substantial heterogeneity of hepatic macrophages during MASH and after VSG. (A) Experimental design, (B) number of sequenced cells per sample, (C) integrated UMAP analysis of monocytes and macrophages and expression of marker genes, (D) heat and dot plot of the expression and coverage of marker genes, (E) pathway analysis of upregulated DEGs in LAMs, compared with all other subsets (gene ontology terms, adj. p < 0.1), and (F) slingshot trajectory analysis (top left) and gene expression over pseudotime for trajectories 1 (top right), 2 (bottom left), and 3 (bottom right) from scRNA-seq of hepatic macrophages and monocytes from Sham AL (n=8), Sham PF (n=8), and VSG (n=8) mice 5–10 weeks after surgeries. Differential expression testing was performed by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; LAM, lipid-associated macrophage; MASH, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; Sham PF, Sham pair-fed; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy.

Following cluster identification, we demultiplexed the samples based on their experimental group and determined the relative abundance of each cluster. Compared with both Sham control groups, VSG had minimal effects on the proportion of macrophages and monocyte clusters (Figure 3A) and average gene expression of Trem2 in LAMs (Figure 3B). Similarly, flow cytometry analysis of hepatic macrophage subsets showed no differences in the frequency and number of total macrophages, KCs, and VSIG4− CLEC2F− macrophages (Supplemental Figure S3A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), which contain the LAMs.11 Because TREM2 is cleaved from hepatic macrophages during MASH and is detectable as sTREM2 in the circulation,14 we assessed its levels in the serum. VSG substantially decreased sTREM2 (Figure 3C), suggesting that the bariatric surgery lessened the inflammation-induced cleavage of TREM2. To assess how VSG altered the gene expression profile of TREM2+ LAMs, we next performed differential gene expression analysis (DGEA) between LAMs from VSG, Sham AL, and Sham PF mice. Compared with both Sham groups, LAMs from VSG mice showed an increased expression of differentially expressed genes involved in lysosomal activity (Ctsl, Ctss, and H2-Eb1), antigen presentation (H2-Eb1), repression of inflammation (Egr1), and fatty acid metabolism (Lipa) (Figure 3D and Supplemental Data File S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I687). In contrast, several genes associated with inflammation (Cd83, Nfkb1, Junb, and Il1a) were downregulated in LAMs from VSG mice (Figure 3D). Consistently, pathway analysis revealed an upregulation of pathways associated with efferocytic activity, such as “antigen processing and presentation,” “phagosome,” and “lysosome” while pathways associated with inflammation, such as “NF-kappa B,” “IL-17,” and “VEGF” signaling were downregulated in VSG LAMs (Figure 3E). As a complementary approach, we performed gene set enrichment analysis and found that genes involved in “TNF alpha signaling via NFkB” such as Nfkb2, Cd80, Cd69, and Il1b, were downregulated in LAMs from VSG mice, compared with Sham controls (Figure 3F). In contrast, VSG resulted in enriched “lysosome” genes such as Lamp1, Ctss, Ctsl, and Ctsw and “fatty acid metabolism” genes including Acadm, Ppard, Acacb, and Mmut (Figure 3F). In MoMFs, VSG upregulated the expression of genes involved in “antigen processing and presentation” and “phagosome” but had no effect on inflammatory or fatty acid metabolism pathways (Supplemental Figure S3B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Among KC clusters, VSG downregulated inflammatory pathways only in KC1 cells (Supplemental Figure S3C, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682) but had minimal effects on the gene expression of KC2 and KC3 clusters (Supplemental Data File S5, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I687). Overall, these data highlight anti-inflammatory, lysosomal, and metabolic regulatory mechanisms by which VSG may sustain a protective function of TREM2+ LAMs against MASH in response to VSG.

FIGURE 3.

VSG enhances lipid metabolism and lysosomal gene programs in hepatic LAMs. (A) UMAPs with cluster IDs for all groups (top) and relative monocyte and macrophage cluster proportions (bottom), (B) UMAPs showing Trem2 expression in monocytes and macrophages (left) and expression of Trem2 in cluster 1 (LAMs) from the scRNA-seq analysis of monocytes and macrophages from Sham AL, Sham PF, or VSG groups 5 weeks after surgery (n = 4). (C) sTREM2 in the serum of NCD (n = 8), Sham AL (n = 7), Sham PF (n = 9), and VSG (n = 8) mice 5 weeks after surgeries. (D) Volcano plots showing DEGs between Sham AL and VSG (left), and Sham PF and VSG (right) LAMs, (E) pathway analysis of LAMs from VSG versus Sham AL (top) and VSG versus Sham PF (bottom) comparisons, (F) GSEA plots of the VSG versus Sham PF LAMs comparison (top), and heatmaps of respective pathways (bottom). sTREM2 levels were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparison test. Differential expression testing was performed by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Pathway analysis was performed by GSEA (adj. p < 0.1). Data are biological experimental units presented as mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; FC, fold change; GSEA, gene seat enrichment analysis; LAM, lipid-associated macrophage; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; Sham PF, Sham pair-fed; sTREM2, soluble TREM2; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy.

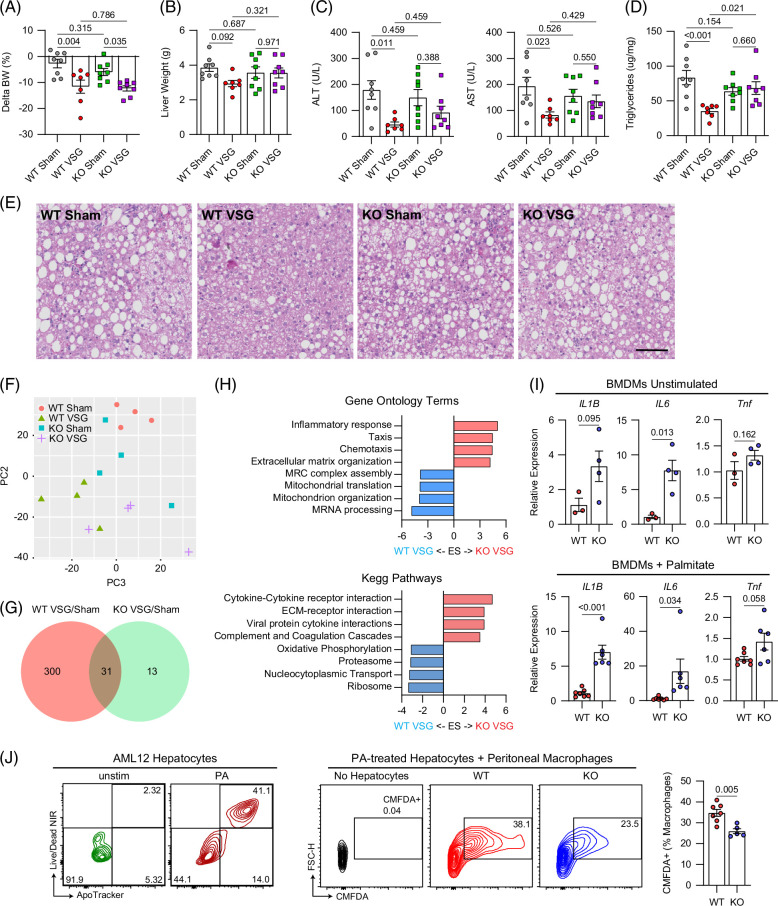

TREM2 is required for the reparative effects of VSG against MASH

To determine if TREM2 directly mediates the reparative process induced by VSG against MASH, we performed sham or VSG surgeries on wild type (WT) and TREM2-deficient (TREM2 KO) mice fed an HFHC diet for 14 weeks. Expression of Trem2 was not detectable in bone marrow–derived macrophages from TREM2 KO mice (Supplemental Figure S4A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). In agreement with our previous experiments, we found that sTREM2 was reduced following VSG in the serum of WT mice and was not detectable in TREM2 KO mice (Supplemental Figure S4B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Five weeks after surgery, WT and TREM2 KO mice showed a similar degree of weight loss (Figure 4A) in response to VSG. However, while VSG ameliorated MASH progression in WT mice, this effect was blunted in TREM2 KO mice (Figures 4B–E). VSG failed to decrease the liver weight (Figure 4B), ALT/AST levels (Figure 4C), and hepatic steatosis (Figures 4D, E) in TREM2 KO mice, suggesting that TREM2 is required for the VSG-induced reversal of MASH. Consistent with our previous experiments, there was a minimal amount of collagen deposition in all groups at this time point, regardless of intervention (Supplemental Figures S4C, D, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). TREM2 KO and WT mice showed a similar increase in fecal lipid excretion (Supplemental Figure S4E, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682) in response to VSG, suggesting that the reduction in intestinal lipid absorption was TREM2-independent. To explore the potential mechanisms by which TREM2 mediates the effects of VSG, we first assessed whether TREM2 deficiency alters the hepatic macrophage populations in mice with MASH before and after VSG. No differences in the number of MoMFs, embryonically derived KCs, monocyte-derived KCs, and VSIG4- macrophages (non-KCs) were detected between HFHC-fed WT and TREM2 KO (Supplemental Figure S4F, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). In addition, the blunted effect of VSG in TREM2 KO mice was not associated with alterations in the number of hepatic macrophage subsets (Supplemental Figure S4G, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). To determine if TREM2 KO mice are resistant to the beneficial effects of VSG due to cell-intrinsic macrophage effects, we sorted and performed bulk RNA sequencing of total hepatic macrophages from WT and TREM2 KO mice after sham or VSG surgeries. Unsupervised principal component analysis showed a distinct separation between WT Sham and WT VSG, whereas there was no distinction between TREM2 KO Sham and TREM2 KO VSG macrophages (Figure 4F). DGEA revealed a more robust response of WT macrophages to VSG (331 differentially expressed genes), compared with that of TREM2 KO cells (44 differentially expressed genes) (Figure 4G and Supplemental Data File S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I688). In agreement, unsupervised clustering of the top 500 most variable genes revealed substantial gene expression differences and clustering between WT Sham and VSG macrophages but not between TREM2 KO Sham and VSG cells (Supplemental Figure S4H, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). DGEA and pathway/gene ontology analyses showed that TREM2 KO macrophages from VSG mice upregulated genes enriched in inflammatory and immune activation pathways such as “cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction” and the gene ontology terms “inflammatory response” and “chemotaxis” (Supplemental Figure S4I, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682 and Figure 4H), suggesting that TREM2 is required for preventing an inflammatory activation of macrophages. To directly test this possibility, we examined the response of bone marrow–derived macrophages from WT and TREM2 KO mice with or without stimulation with palmitate in vitro to mimic the lipid-rich environment of the MASH liver. Compared with WT controls, TREM2 KO bone marrow–derived macrophages showed an increased expression of Il1b, Il6, and Tnf, regardless of stimulation (Figure 4I). We next determined whether TREM2 facilitates the ability of macrophages to clear apoptotic cells. We induced apoptosis in AML12 hepatocytes by palmitate treatment and cocultured them with either WT or TREM2 KO peritoneal macrophages. Consistent with its key role in efferocytosis, TREM2 was required for macrophages to perform effective efferocytosis of lipid-laden apoptotic hepatocytes (Figure 4J). Together, these data suggest that hepatic macrophages mediate the VSG-induced reversal of MASH by repressing inflammation and facilitating efferocytosis in a TREM2-dependent manner.

FIGURE 4.

TREM2 is required for the reparative effects of VSG against MASH. (A) Body weight change after surgery, (B) liver weight, (C) serum ALT (left) and AST (right), (D) hepatic triglyceride content, (E) representative H&E-stained liver sections, (F) unsupervised PCA of bulk RNA-seq gene expression data from F4/80+-sorted macrophages, (G) Venn diagram with the number of DEGs between Sham and VSG in WT and TREM2 KO macrophages, and (H) pathway analysis (KEGG and gene ontology) for the TREM2 KO VSG versus WT VSG comparison. C57BL6/J (WT) and TREM2 KO (KO) mice were fed an HFHC diet for 14 weeks, assigned to either Sham AL or VSG, and analyzed 5 weeks after surgery (WT Sham, n = 4–8; WT VSG, n = 4–7; KO Sham, n = 4–8; and KO VSG, n = 4–8). (I) Gene expression of inflammatory cytokines in bone marrow–derived macrophages from WT (n = 3–7) or TREM2 KO (n = 4–6) mice left unstimulated (left) or stimulated with palmitate (right). (J) Representative flow plots showing apoptosis of AML12 hepatocytes that were either left unstimulated or stimulated with PA (left), and representative plots (middle) and quantification (right) of CellTracker Green (CMFDA)-positive macrophages following coculture of peritoneal macrophages from WT (n = 7) and TREM2 KO (n =5) mice with CMFDA-labeled apoptotic AML12 hepatocytes. Data from 4 experimental groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparison test. Pathway analysis was performed by GSEA (adj. p < 0.1). Data from 2 experimental groups were analyzed by Mann-Whitney tests. Data are biological experimental units presented as mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; GSEA, gene seat enrichment analysis; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HFHC, high-fat high-carbohydrate; KO, knockout; MASH, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis; PA, palmitate; PCA, principal component analysis; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy; WT, wild type.

VSG increases the content of inflammatory lipid species in hepatic macrophages

Because total liver triacylglycerols (TGs) decreased in response to VSG while hepatic LAMs upregulate lipid metabolism genes, we performed metabolic profiling of liver tissue and sorted F4/80+ macrophages from Sham AL and VSG livers to determine how bariatric surgery alters their lipid content. Metabolite profiling (MxP Quant 500 kit, Biocrates) revealed 317 unique detectable metabolites in macrophages, predominantly TGs and phosphatidylcholines (Figure 5A). Unsupervised principal component analysis showed a moderate clustering of VSG samples with more separation among Sham AL specimens (Figure 5B). We found no difference in the concentration of total TGs in the macrophages from Sham AL and VSG mice (Figure 5C). However, when we performed chain length enrichment analysis, we found that macrophages from Sham AL mice were enriched in species with longer chain lengths, while those from VSG mice were enriched in species of shorter chain lengths (Figure 5D). Quantification of the major lipid families showed that macrophages from VSG mice had increased total phosphatidylcholines and sphingolipids but no changes in cholesterol esters, fatty acids, glycosylceramides, ceramides, sphingolipids, and diacylglycerols (Figure 5E). To further assess the effects of VSG on the lipid profile of hepatic macrophages, we assessed the composition of the individual lipid species. VSG macrophages had increased levels of phosphatidylcholines, particularly species containing 2 acyl-bound (aa), 1 acyl-, and 1 alkyl-bound (ae), and monounsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5F). VSG macrophages were also enriched in sphingomyelins containing long and very-long-chain fatty acids (Figure 5G), as well as ceramides containing very-long-chain fatty acids (Figure 5H). Although there were trending increases in VSG macrophages, we were unable to detect significant differences in the content of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5I) and cholesterol esters (Figure 5J) compared with Sham controls. In the liver, we detected 302 total metabolites with a high proportion of TGs and phosphatidylcholines. In contrast with macrophages, hepatic tissue from VSG mice had a substantial decrease in TGs and a trending decrease in total diacylglycerols and cholesterol esters. At the same time, phosphatidylcholines, ceramides, and sphingolipids remained unchanged (Supplemental Figures S5A–F, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). The VSG-to-Sham AL ratio showed that while VSG resulted in an overall decreased content in hepatic tissue, macrophages from VSG mice were enriched in lipid families (Figure 5K), suggesting an improved ability to clear lipids after the surgery.

FIGURE 5.

VSG increases the content of inflammatory lipid species in hepatic macrophages. (A) Composition of detectable metabolites in macrophages, (B) unsupervised PCA of metabolite data, (C) concentration of TGs, (D) chain length enrichment analysis of all lipid species, (E) concentration of major lipid species including PC, CEs, FAs, HexCer, Cer, SM, and DGs, (F) PC subspecies such as PCs (aa), PCs (ae), MUFA PCs, PUFA PCs, and SFA PCs, (G) SM subspecies including LCFA SMs and VLCFA SMs, (H) Cer subspecies including VLCFA-Cer and LCFA-Cer, (I) FA subspecies including MUFAs, PUFAs, and w-3 FAs, and (J) CE subspecies determined by mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography of hepatic macrophages isolated from the livers of HFHC-fed mice assigned to Sham AL (n = 4) or VSG (n = 4) 5 weeks after surgery. (K) Heatmap of the VSG/Sham AL ratio for lipid species in the liver and macrophages (mac) showing the p values for each comparison. Data were analyzed by the Welch 2-sided t tests. Data are biological experimental units presented as mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: CE, cholesterol ester; Cer, ceramides; DG, diacylglycerol; FA, fatty acid; HexCer, glycosylceramides; HFHC, high-fat high-carbohydrate; LCFA, long chain fatty acid; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PC, phosphatidylcholines; PCA, principal component analysis; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; SM, sphingolipids; TG, triacylglycerols; VLCFA, very-long-chain fatty acid; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy; w-3, omega-3.

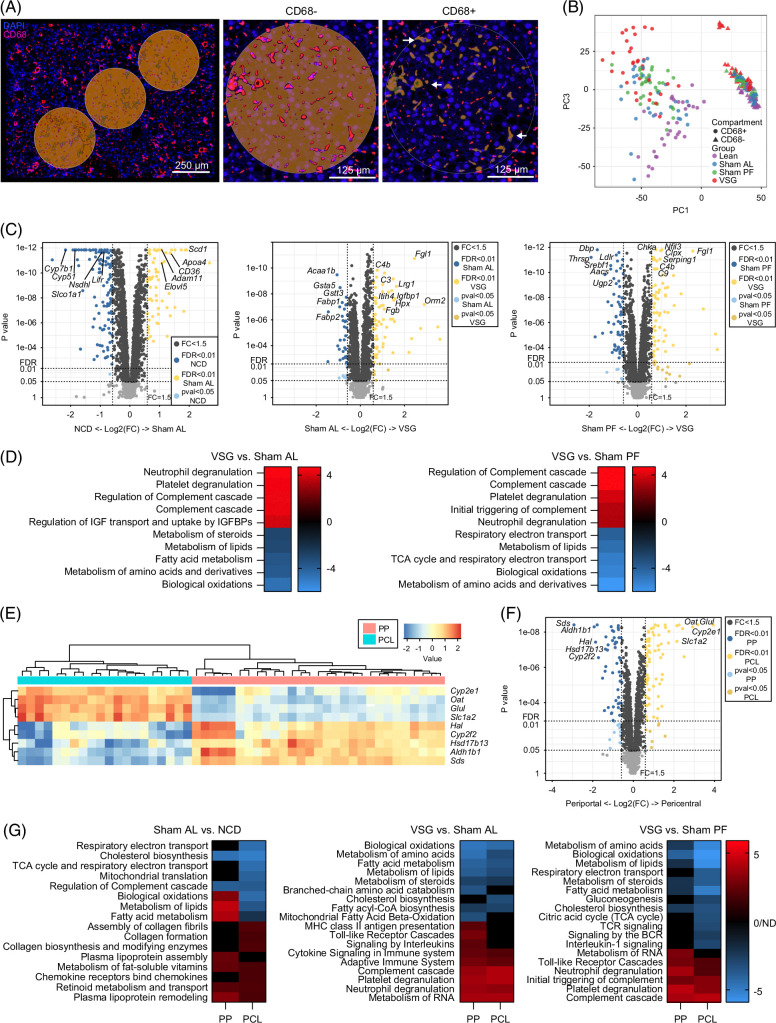

Spatial transcriptomic of MASH livers following bariatric surgery reveal an improved metabolic status in the macrophage microenvironment

We next explored the effects of VSG on the hepatic areas surrounding macrophages using spatial transcriptomic analysis of liver sections (Nanostring GeoMx). Tissues from NCD, Sham AL, Sham PF, and VSG mice were collected 5 weeks after surgery and stained with a fluorescently labeled antibody against the macrophage marker CD68 to capture gene expression changes in CD68− microanatomic areas (Figure 6A). Following imaging and sequencing, the initial data were subjected to quality checks, filtering, and scaling, leading to a total of 7074 detectable genes and 32–36 ROIs per group. We confirmed the specificity of CD68 segmentation by assessing the expression of macrophage marker genes, Adgre1, Mertk, and Fcgr3, which were undetectable in the CD68− areas (Supplemental Figure S6A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Unsupervised principal component analysis of the normalized genes showed a substantial separation between CD68-expressing ROIs, and, to a lesser extent, between experimental groups (Figure 6B). Due to the small size of their ROIs (Supplemental Figure S6B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), we were unable to detect meaningful gene expression data from the CD68+ macrophage areas. Deconvolution analysis of the spatial transcriptomic data based on our scRNA-seq data showed very low detection of macrophage subsets (Supplemental Figure S6C, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). On the other hand, DGEA of the CD68− ROIs revealed 185, 103, and 139 differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate <0.05, fold change >1.5; Supplemental Data File S7, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I689) between NCD versus Sham AL, Sham AL versus and VSG, and Sham PF versus VSG, respectively (Figure 6C). We then performed enrichment and pathway analyses that covered a wide range of cellular pathways, including “metabolism,” “immune system,” “signal transduction,” and “metabolism of proteins” (Supplemental Figure S6D, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Compared with Sham AL and PF controls, VSG downregulated pathways involved in “biological oxidations” and “metabolism of lipids” in agreement with the reduced lipid accumulation observed in VSG mice. In contrast, VSG upregulated pathways such as “degranulation of neutrophils/platelets” and “complement cascade” indicative of an active immune and tissue remodeling response (Figure 6D). We identified ROIs that localized to periportal (PP) and pericentral (PCL) zones based on the spatial expression of central (Slc1a2, Glul, Oat, and Cyp2e1) and portal (Sds, Aldh1b1, Cyp2f2, and Hal) gene markers26 (Figure 6E). Unbiased DGEA between PP and PCL ROIs revealed a strong association between zonation marker genes for the PCL and PP regions (Figure 6F). Relative to NCD controls, ROIs from Sham AL mice had upregulated pathways related to lipid metabolism in the PP ROIs, while collagen formation pathways were preferentially increased in the PCL ROIs (Figure 6G, left). Compared with both Sham AL and PF groups, VSG downregulated pathways associated with the metabolism of lipids and amino acids without notable differences between PP and PCL ROIs. Conversely, VSG upregulated immune pathways indicative of an active immune and tissue remodeling response, such as the degranulation of neutrophils and complement cascade in both PP and PCL ROIs (Figure 6G, middle and right). Notably, VSG decreased the expression of pathways associated with immune activation, such as B-cell receptor, T-cell receptor, and interleukin 1 signaling exclusively in the PCL ROIs (Figure 6G, right). Overall, these findings highlight the VSG-induced transcriptomic changes in metabolic and immune pathways in the microenvironment surrounding hepatic macrophages that are associated with MASH reversal.

FIGURE 6.

Spatial transcriptomics of MASH livers following bariatric surgery reveals an improved metabolic status in the macrophage microenvironment. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of ROIs (left) and magnified fields showing CD68− (middle) and CD68+ (right) areas in liver specimens analyzed by spatial transcriptomics (Geomx). (B) Unsupervised PCA of gene expression data from CD68+ and CD68− ROIs. (C) Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes between NCD and Sham AL (left), Sham AL and VSG (middle), Sham PF and VSG (right) CD68− ROIs. (D) Pathway analysis of VSG versus Sham AL (left) and VSG versus Sham PF (right). (E) Heatmap of zonation marker genes for PP and PCL ROIs. (F) Volcano plots showing DEGs between PP and PCL ROIs. (G) Pathway analysis of PP and PCL ROIs for the NCD and Sham AL (left), Sham AL and VSG (middle), and Sham PF and VSG comparisons (right). Liver specimens were collected from C57BL6/J (WT) fed either an NCD or an HFHC diet for 14 weeks, assigned to Sham AL, Sham PF, or VSG surgeries, and analyzed 5 weeks after surgery (n = 4). Data were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test and corrected with a Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Pathway analysis was performed by GSEA (adj. p < 0.1). Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; HFHC, high-fat high-carbohydrate; NCD, normal chow diet; PCA, principal component analysis; PCL, pericentral; PP, periportal; ROI, regions of interest; Sham AL, Sham ad libitum; Sham PF, Sham pair-fed; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy; WT, wild type.

To determine whether our main findings could be relevant to human patients with MASH undergoing VSG, we performed spatial transcriptomics on needle biopsy specimens from a patient with MASH, collected before and 1 year after VSG that resulted in the resolution of MASH (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). We also included a liver specimen from a donor patient with MASH without any surgical intervention. After staining with cytokeratin (green) and the macrophage marker CD68 (magenta), 32 ROIs were annotated to define hepatic zones PP, mid-lobular, and PCL (Supplemental Figure S6E, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). Pathway analysis of these comparisons revealed several downregulated pathways involved in the “metabolism of lipids,” “cholesterol biosynthesis,” and “metabolism of steroids” (Supplemental Figure S6F, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), consistent with the MASH resolution observed in this patient. To explore how human LAMs respond to VSG, we assessed the expression of genes involved in the LAM differentiation program, including Trem2, Plin2, Ctss, Cd36, and Lipa. 15 LAM genes were primarily enriched in PP regions of the liver (Supplemental Figure S6G, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682), in agreement with a recently published spatial transcriptomic study.13 Furthermore, the LAM genes were upregulated in the pre-VSG and MASH samples but decreased in the post-VSG specimen (Supplemental Figure S6G, http://links.lww.com/HEP/I682). These data suggest that, while LAMs expand during MASH, the LAM phenotype is no longer present upon VSG-induced MASH resolution.

DISCUSSION

The beneficial effects of bariatric surgeries against obesity-related diseases are usually attributed to the mechanical restriction of the stomach and malabsorption of nutrients. However, accumulating evidence shows that the surgeries exert profound effects in the regulation of several physiological functions ranging from caloric intake,27 intestinal BAs and lipid absorption,28 iron metabolism,10 and immune responses.29 Here, we show that VSG induces weight-loss–independent improvements in disease pathogenesis in a process that requires TREM2. These data implicate the innate immune system in the control of inflammation as an important mechanism of VSG action. Previous work has shown that systemic inflammatory mediators associated with obesity gradually decline following bariatric surgery in humans30 and mouse models of disease.31 As TREM2 KO mice do not respond to the surgery and TREM2-deficient macrophages have increased inflammatory gene expression and reduced efferocytosis, these findings demonstrate that TREM2 mediates the reparative process induced by VSG through enhanced clearance of dying hepatocytes and reduced macrophage-mediated inflammation.

Here, we show that TREM2 is necessary for the VSG-induced disease reversal in a process associated with a sustained expression and decreased shedding of TREM2. Mechanistically, TREM2 is required for dampening inflammation and effective efferocytosis of lipid-laden hepatocytes by macrophages. Given that TREM2 is a master regulator of the LAM phenotype,25 we reasoned that TREM2 would mediate their reparative role induced by VSG. Our findings indicate that VSG restores several TREM2 signaling pathways, such as “AKT-PI3K signaling,” required for effective suppression of inflammation,32 and “oxidative phosphorylation,” typical of macrophages in anti-inflammatory or reparative states.33 As the potential ligands of TREM2 include bacterial products,34 gut-derived microbial products may have direct effects on hepatic LAMs or other macrophage subsets through pattern recognition receptors35 or gut-derived metabolites drained through the portal vein.36 For example, increased intestinal butyrate may be an additional mechanism by which VSG induces a reparative macrophage phenotype as VSG restores the levels of butyrate-producing Lactobacillus. 37

Given that the local microenvironment has a profound impact on the transcriptional program and function of macrophages, we used spatial transcriptomics to assess the effects of VSG on hepatic macrophage-adjacent areas. In agreement with reduced steatosis, lipid metabolism pathways were suppressed by VSG in nonmacrophage areas, suggesting that VSG can enhance the ability of macrophages to take up and metabolize lipids. In support of this notion, macrophages from VSG mice are enriched in lipid species while the liver presents with decreased steatosis. Following VSG, the content of several lipid families decreases in the liver, while hepatic macrophages increase their levels of intracellular phosphatidylcholines and sphingolipids. The role of phosphatidylcholines in macrophages is unclear, with studies reporting both proinflammatory38 and anti-inflammatory39 responses. In addition, one of the main immune pathways upregulated following VSG was the complement system. This was surprising as increased levels of complement proteins can increase hepatic de novo lipogenesis, inflammation, and insulin resistance.40 Additional studies are needed to determine if complement proteins play a role in the response of the MASH liver to VSG due to the limited biological implications that can be drawn from transcriptomic data.

One limitation of our study is that we used a mouse with a systemic TREM2 deficiency. Although TREM2 is primarily expressed by myeloid cells, bacterial and viral infections have been reported to induce TREM2 expression in CD4 T cells.41 In addition, TREM2-expressing macrophages in the adipose tissue have been shown to prevent obesity and adiposity, which could influence the development of hepatic steatosis.25 While several key experiments, such as our scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics analyses, show that hepatic LAMs are responsive to VSG, we cannot rule out the potential contribution of adipose tissue LAMs to the VSG-induced protective effects in the liver. Another limitation of our experiments is that the bulk RNA-seq analysis of WT and TREM2-deficient macrophages in response to VSG was performed in total F4/80+ cells. Thus, we were unable to distinguish gene expression differences between subpopulations, and subtle transcriptional effects of TREM2 deficiency may have been masked.

Supplementary Material

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Raw and processed data for this study have been deposited at the NCBI GEO (GSE276019).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xavier S. Revelo, Gavin Fredrickson, and Sayeed Ikramuddin conceived the study and designed experiments. Gavin Fredrickson and Xavier S. Revelo interpreted results, generated figures and tables, and wrote the manuscript. Gavin Fredrickson, Kira Florczak, Fanta Barrow, Shamsed Mahmud, Katrina Dietsche, Haiguang Wang, Preethy Parthiban, Andrew Hakeem, Cyrus Jahansouz, Christopher Staley, and Rawan Almutlaq performed experiments or reviewed the manuscript. Oyedele Adeyi analyzed and provided data from liver specimens. Adam Herman performed the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Alessandro Bartolomucci, Cyrus Jahansouz, Xiao Dong, Jesse W. Williams, and Douglas G. Mashek provided feedback and supervised aspects of the study. Xavier S. Revelo obtained funding for, supervised, and led the overall execution of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors recognize the staff from the Research Animal Resources, University Flow Cytometry Resource, Center for Metabolomics and Proteomics, Genomics Center, and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the University of Minnesota for their assistance.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by grants from the NIDDK (DK122056 to Xavier S. Revelo and DK128325 to Sayeed Ikramuddin), NHLBI (R01HL155993 to Xavier S. Revelo and R01HL166843 to Jesse W. Williams), NIAID (P01AI172501 to Xiao Dong and Xavier S. Revelo), and a Department of Surgery Bianco Seed Fund award (to Xavier S. Revelo and Sayeed Ikramuddin). Gavin Fredrickson and Shamsed Mahmud are supported by T32 NIH training grants (T32DK083250 and AG029796).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Xiao Dong owns stock in SingulOmics Corp. The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Xavier S. Revelo is the lead contact.

Abbreviations: BA, bile acids; DGEA, differential gene expression analysis; FA, fatty acids; HFHC, high-fat high-carbohydrate; KO, knockout; LAMs, lipid-associated macrophages; MASH, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease; MoMFs, monocyte-derived macrophages; NCD, normal chow diet; PCL, pericentral; PP, periportal; ROI, regions of interest; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; Sham AL, sham ad-libitum-fed; Sham PF, sham pair-fed; sTREM2, soluble TREM2; TG, triacylglycerols; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; VSG, vertical sleeve gastrectomy; WT, wild type.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Gavin Fredrickson, Email: fredr300@umn.edu.

Kira Florczak, Email: florc138@umn.edu.

Fanta Barrow, Email: fbarrow@umn.edu.

Shamsed Mahmud, Email: mahmu052@umn.edu.

Katrina Dietsche, Email: katrina.dietsche@yale.edu.

Haiguang Wang, Email: wang4226@umn.edu.

Preethy Parthiban, Email: parth034@umn.edu.

Andrew Hakeem, Email: hakee009@umn.edu.

Rawan Almutlaq, Email: almut051@umn.edu.

Oyedele Adeyi, Email: Adeyio@umn.edu.

Adam Herman, Email: aherman@umn.edu.

Alessandro Bartolomucci, Email: abartolo@umn.edu.

Christopher Staley, Email: cmstaley@umn.edu.

Xiao Dong, Email: dong0265@umn.edu.

Cyrus Jahansouz, Email: jahan023@umn.edu.

Jesse W. Williams, Email: jww@umn.edu.

Douglas G. Mashek, Email: dmashek@umn.edu.

Sayeed Ikramuddin, Email: ikram001@umn.edu.

Xavier S. Revelo, Email: xrevelo@umn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster S, Cabrera D, Arrese M, Feldstein AE. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:349–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherla DV, Rodriguez NA, Vangoitsenhoven R, Singh T, Mehta N, McCullough AJ, et al. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2266–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Froylich D, Corcelles R, Daigle C, Boules M, Brethauer S, Schauer P. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzello M, Abbatini F, Casella G, Alessandri G, Fantini A, Leonetti F, et al. Early postoperative insulin-resistance changes after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.le Roux CW, Welbourn R, Werling M, Osborne A, Kokkinos A, Laurenius A, et al. Gut hormones as mediators of appetite and weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2007;246:780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeidi N, Meoli L, Nestoridi E, Gupta NK, Kvas S, Kucharczyk J, et al. Reprogramming of intestinal glucose metabolism and glycemic control in rats after gastric bypass. Science. 2013;341:406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahansouz C, Staley C, Bernlohr DA, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A, Ikramuddin S. Sleeve gastrectomy drives persistent shifts in the gut microbiome. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evers SS, Shao Y, Ramakrishnan SK, Shin JH, Bozadjieva-Kramer N, Irmler M, et al. Gut HIF2α signaling is increased after VSG, and gut activation of HIF2α decreases weight, improves glucose, and increases GLP-1 secretion. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remmerie A, Martens L, Thoné T, Castoldi A, Seurinck R, Pavie B, et al. Osteopontin expression identifies a subset of recruited macrophages distinct from Kupffer cells in the fatty liver. Immunity. 2020;53:641–657.e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong X, Kuang H, Ansari S, Liu T, Gong J, Wang S, et al. Landscape of intercellular crosstalk in healthy and NASH liver revealed by single-cell secretome gene analysis. Mol Cell. 2019;75:644–660.e645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guilliams M, Bonnardel J, Haest B, Vanderborght B, Wagner C, Remmerie A, et al. Spatial proteogenomics reveals distinct and evolutionarily conserved hepatic macrophage niches. Cell. 2022;185:379–396.e338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, He Q, Zhou C, Xu Y, Liu D, Fujiwara N, et al. Prolonged hypernutrition impairs TREM2-dependent efferocytosis to license chronic liver inflammation and NASH development. Immunity. 2023;56:58–77.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendrikx T, Porsch F, Kiss MG, Rajcic D, Papac-Miličević N, Hoebinger C, et al. Soluble TREM2 levels reflect the recruitment and expansion of TREM2(+) macrophages that localize to fibrotic areas and limit NASH. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1373–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou J, Zhang J, Cui P, Zhou Y, Liu C, Wu X, et al. TREM2 sustains macrophage-hepatocyte metabolic coordination in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e135197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perugorria MJ, Esparza-Baquer A, Oakley F, Labiano I, Korosec A, Jais A, et al. Non-parenchymal TREM-2 protects the liver from immune-mediated hepatocellular damage. Gut. 2019;68:533–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deczkowska A, Weiner A, Amit I. The physiology, pathology, and potential therapeutic applications of the TREM2 signaling pathway. Cell. 2020;181:1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson MT, Xu Y, Hillman H, Osinski V, Schrank PR, Kennedy AE, et al. Trem2 agonist reprograms foamy macrophages to promote atherosclerotic plaque stability—Brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024;44:1646–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrow F, Khan S, Fredrickson G, Wang H, Dietsche K, Parthiban P, et al. Microbiota-driven activation of intrahepatic B cells aggravates NASH through innate and adaptive signaling. Hepatology. 2021;74:704–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zollinger DR, Lingle SE, Sorg K, Beechem JM, Merritt CR. GeoMx™ RNA assay: High multiplex, digital, spatial analysis of RNA in FFPE tissue. In: Nielsen BS, Jones J, eds. In Situ Hybridization Protocols. Springer US; 2020:331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Zvi D, Meoli L, Abidi WM, Nestoridi E, Panciotti C, Castillo E, et al. Time-dependent molecular responses differ between gastric bypass and dieting but are conserved across species. Cell Metab. 2018;28:310–323.e316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran S, Baba I, Poupel L, Dussaud S, Moreau M, Gélineau A, et al. Impaired Kupffer cell self-renewal alters the liver response to lipid overload during non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Immunity. 2020;53:627–640.e625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blériot C, Barreby E, Dunsmore G, Ballaire R, Chakarov S, Ficht X, et al. A subset of Kupffer cells regulates metabolism through the expression of CD36. Immunity. 2021;54:2101–2116.e2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaitin DA, Adlung L, Thaiss CA, Weiner A, Li B, Descamps H, et al. Lipid-associated macrophages control metabolic homeostasis in a Trem2-dependent manner. Cell. 2019;178:686–698.e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildebrandt F, Andersson A, Saarenpää S, Larsson L, Van Hul N, Kanatani S, et al. Spatial transcriptomics to define transcriptional patterns of zonation and structural components in the mouse liver. Nat Commun. 2021;12:7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.le Roux CW, Bueter M. The physiology of altered eating behaviour after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding L, Zhang E, Yang Q, Jin L, Sousa KM, Dong B, et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy confers metabolic improvements by reducing intestinal bile acids and lipid absorption in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2019388118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gihring A, Gärtner F, Mayer L, Roth A, Abdelrasoul H, Kornmann M, et al. Influence of bariatric surgery on the peripheral blood immune system of female patients with morbid obesity revealed by high-dimensional mass cytometry. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1131893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biobaku F, Ghanim H, Monte SV, Caruana JA, Dandona P. Bariatric surgery: Remission of inflammation, cardiometabolic benefits, and common adverse effects. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4:bvaa049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn CH, Choi EH, Lee H, Lee W, Kim JI, Cho YM. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy induces distinctive transcriptomic responses in liver, fat and muscle. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Lin Y, Wang L, Zhan H, Luo X, Zeng Y, et al. TREM2 ameliorates neuroinflammatory response and cognitive impairment via PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:20862–20879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rasheed A, Rayner KJ. Macrophage responses to environmental stimuli during homeostasis and disease. Endocr Rev. 2021;42:407–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daws MR, Sullam PM, Niemi EC, Chen TT, Tchao NK, Seaman WE. Pattern recognition by TREM-2: Binding of anionic ligands. J Immunol. 2003;171:594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver LK, Minichino D, Biswas C, Chu N, Lee JJ, Bittinger K, et al. Microbiota-dependent signals are required to sustain TLR-mediated immune responses. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e124370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abu-Gazala S, Horwitz E, Ben-Haroush Schyr R, Bardugo A, Israeli H, Hija A, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy improves glycemia independent of weight loss by restoring hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2018;67:1079–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulker İ, Yildiran H. The effects of bariatric surgery on gut microbiota in patients with obesity: A review of the literature. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2019;38:3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cauvi DM, Hawisher D, Derunes J, De Maio A. Phosphatidylcholine liposomes reprogram macrophages toward an inflammatory phenotype. Membranes. 2023;13:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treede I, Braun A, Sparla R, Kühnel M, Giese T, Turner JR, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of phosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27155–27164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo Z, Fan X, Yao J, Tomlinson S, Yuan G, He S. The role of complement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1017467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Y, Wu M, Ming S, Zhan X, Hu S, Li X, et al. TREM-2 promotes Th1 responses by interacting with the CD3ζ-ZAP70 complex following Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e137407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]