Abstract

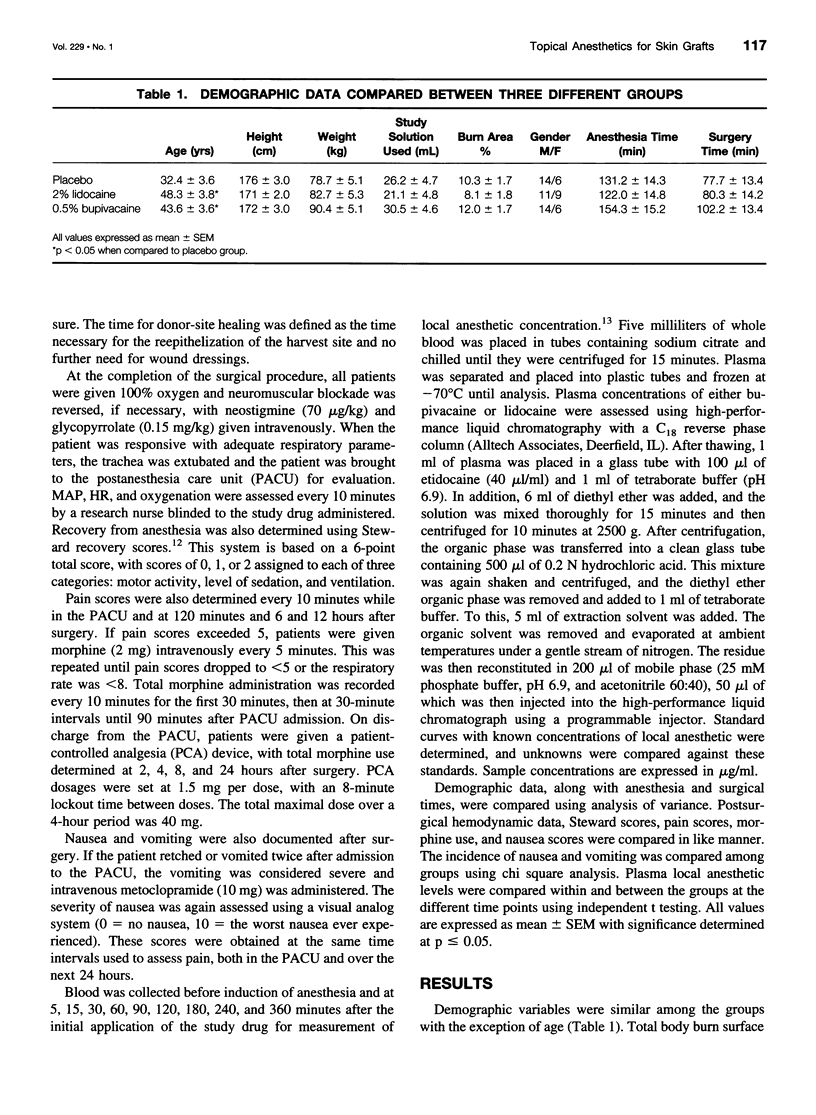

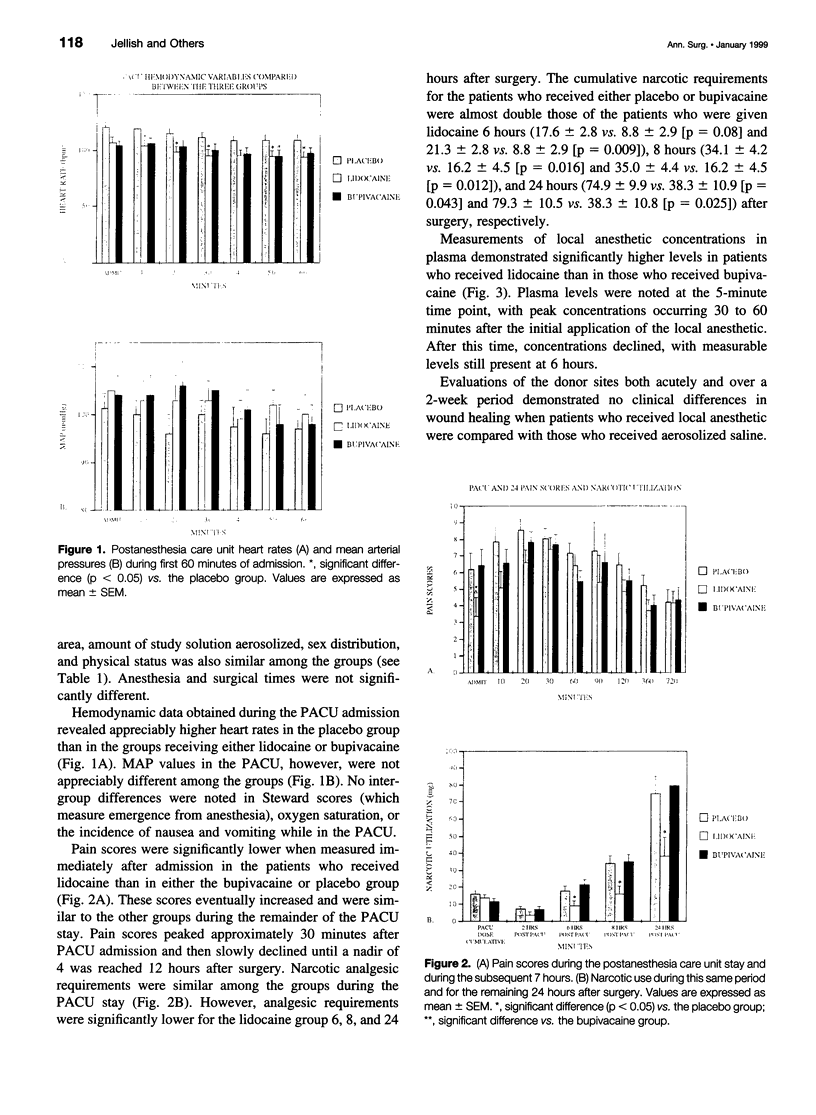

OBJECTIVE: To determine if topical administration of local anesthesia, applied to fresh skin-harvest sites, reduces pain and analgesic requirements after surgery. SUMMARY BACKGROUND DATA: Nonopioid treatments for pain after therapeutic procedures on patients with burns have become popular because of the side effects associated with narcotics. The topical administration of local anesthesia originally offered little advantage because of poor epidermal penetration. METHODS: This study compares 2% lidocaine with 0.5% bupivacaine or saline, topically applied after skin harvest, to determine what effect this may have on pain and narcotic use. Sixty patients with partial- or full-thickness burns to approximately 10% to 15% of their body were randomly divided into three groups: group 1 received normal saline, group 2 had 0.5% bupivacaine, and group 3 had 2% lidocaine sprayed onto areas immediately after skin harvest. Blood samples were subsequently obtained to measure concentrations of the local anesthetic. Hemodynamic variables after surgery, wake-up times, emetic symptoms, pain, and narcotic use were compared. RESULTS: Higher heart rates were noted in the placebo group than in those receiving lidocaine or bupivacaine. No differences were noted in recovery from anesthesia or emetic symptoms. Pain scores were lower and 24-hour narcotic use was less in patients who received lidocaine. Plasma lidocaine levels were greater than bupivacaine at all time points measured. CONCLUSIONS: Topical lidocaine applied to skin-harvest sites produced an analgesic effect that reduced narcotic requirements compared with patients who received bupivacaine or placebo. Local anesthetic solutions aerosolized onto skin-harvest sites did not affect healing or produce toxic blood concentrations.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arens J. F., Carrera A. E. Methemoglobin levels following peridural anesthesia with prilocaine for vaginal deliveries. Anesth Analg. 1970 Mar-Apr;49(2):219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn M. A. Burn pain: the management of procedure-related pain. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995 May-Jun;16(3 Pt 2):365–371. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199505001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choinière M., Melzack R., Rondeau J., Girard N., Paquin M. J. The pain of burns: characteristics and correlates. J Trauma. 1989 Nov;29(11):1531–1539. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198911000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J. B., Brennum J., Arendt-Nielsen L., Jensen T. S., Kehlet H. The effect of pre- versus postinjury infiltration with lidocaine on thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia after heat injury to the skin. Pain. 1993 Apr;53(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90054-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson A. S., Sinclair R., Cassuto J., Thomsen P. Influence of lidocaine on leukocyte function in the surgical wound. Anesthesiology. 1992 Jul;77(1):74–78. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddon D. B., Lindhe J. In vivo quantitation of local anesthetic suppression of leukocyte adherence. Am J Pathol. 1972 Aug;68(2):327–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha H. R., Funk B., Gerber H. R., Follath F. Determination of bupivacaine in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anesth Analg. 1984 Apr;63(4):448–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. J., Jones D. A., Harris E. J. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation in muscle homogenates by phospholipase A2 inhibitors. Biosci Rep. 1984 Jul;4(7):581–587. doi: 10.1007/BF01121915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson A., Cassuto J., Hanson B. Inhibition of burn pain by intravenous lignocaine infusion. Lancet. 1991 Jul 20;338(8760):151–152. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90139-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundell J. C., Silverman D. G., Brull S. J., O'Connor T. Z., Kitahata L. M., Collins J. G., LaMotte R. Reduction of postburn hyperalgesia after local injection of ketorolac in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1996 Mar;84(3):502–509. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. C., Hickman L. C., Lemasters G. K. A distraction technique for control of burn pain. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1992 Sep-Oct;13(5):576–580. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møiniche S., Dahl J. B., Brennum J., Kehlet H. No antiinflammatory effect of short-term topical and subcutaneous administration of local anesthetics on postburn inflammation. Reg Anesth. 1993 Sep-Oct;18(5):300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møiniche S., Pedersen J. L., Kehlet H. Topical ketorolac has no antinociceptive or anti-inflammatory effect in thermal injury. Burns. 1994 Dec;20(6):483–486. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. R., Goldberg M. L., Ehde D. M. Hypnosis in the treatment of patients with severe burns. Am J Clin Hypn. 1996 Jan;38(3):200–213. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1996.10403338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. L., Callesen T., Møiniche S., Kehlet H. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of lignocaine-prilocaine (EMLA) cream in human burn injury. Br J Anaesth. 1996 Jun;76(6):806–810. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. L., Crawford M. E., Dahl J. B., Brennum J., Kehlet H. Effect of preemptive nerve block on inflammation and hyperalgesia after human thermal injury. Anesthesiology. 1996 May;84(5):1020–1026. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. L., Møiniche S., Kehlet H. Topical glucocorticoid has no antinociceptive or anti-inflammatory effect in thermal injury. Br J Anaesth. 1994 Apr;72(4):379–382. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. B., Jebson P. J., Braid D. P., Ortengren B., Frisch P. Factors affecting plasma levels of lignocaine and prilocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1972 Oct;44(10):1040–1049. doi: 10.1093/bja/44.10.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbert B. S., Lipkowski A. W., Cepeda M. S., Szyfelbein S. K., Osgood P. F., Carr D. B. Enhanced potency of receptor-selective opioids after acute burn injury. Anesth Analg. 1991 Oct;73(4):427–433. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward D. J. A simplified scoring system for the post-operative recovery room. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1975 Jan;22(1):111–113. doi: 10.1007/BF03004827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Long G., Mather L. E. Plasma lignocaine concentrations following topical aerosol application. Br J Anaesth. 1969 May;41(5):442–446. doi: 10.1093/bja/41.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H. T., Ackerman B. H., Wardius P. A., Haith L. R., Jr, Patton M. L. Intravenous ketorolac for pain management in a ventilator-dependent patient with thermal injury. Pharmacotherapy. 1996 Jan-Feb;16(1):75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]