Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for new malaria vaccines with > 90% efficacy against Plasmodium falciparum infection to expand the anti-disease benefit provided by the RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix M subunit vaccines currently administered to infants and young children in sub-Saharan Africa. Attenuated P. falciparum sporozoites (PfSPZ) are being developed as a traveller’s vaccine and to fulfill WHO’s call for high-level efficacy in endemic countries to support malaria elimination.

Methods

PfSPZ Vaccine, comprised of radiation-attenuated PfSPZ, was compared with normal saline placebo in a randomized, double-blind trial targeting 60 malaria-naive US adults to assess safety, tolerability, immunogenicity, and efficacy against heterologous controlled human malaria infection three and twelve weeks after immunization. Pharmacists provided syringes to blinded clinicians using 3:1 (vaccine:placebo) blocked randomization, for administration by direct venous inoculation on days 1 and 8 (multidose prime) and day 29 (boost), a condensed regimen with superior efficacy. Primary outcomes included adverse events and antibody responses to the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (PfCSP).

Results

31 participants were screened, randomized and immunized twice (V1, V2) 5–7 days apart, with one withdrawal after an intercurrent adverse event. A vial issue, later traced to the vial manufacturer, halted further immunizations. Solicited local and systemic adverse events recorded for 2 and 7 days after immunizations, respectively, occurred with equal frequency and severity in the 23 vaccinees and 7 controls receiving two immunizations, as did unsolicited adverse events recorded for 28 days and laboratory abnormalities 1 and 5 weeks after V2. Four of 23 vaccinees and one of 7 controls (p = 1.00) developed grade 2 adverse events including subjective fever, headache, malaise, fatigue, rigors, arthralgia and myalgia after V2 but not V1, these symptoms generally resolving within 24 h. Twenty-two of 23 (96%) vaccinees developed IgG (median 99-fold increase over baseline) and IgM (median 1,110-fold increase) antibodies to PfCSP one week after V2. Antibody responses were not associated with reactogenicity.

Conclusions

The two-dose priming immunization regimen was safe, well tolerated and highly immunogenic. Larger studies may better define the adverse event profile of condensed regimens of PfSPZ Vaccine in malaria-naive adults.

Trial registration number: clinicaltrial.gov NCT05604521.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12936-025-05299-5.

Keywords: PfSPZ, Vaccines, Plasmodium falciparum, Malaria, Safety, Immunogenicity, Clinical trials

Background

Malaria, an ancient scourge, continues unabated, with 263 million clinical cases and 597 thousand deaths recorded in 2023 by the World Health Organization (WHO), numbers essentially unchanged since 2012 despite the annual expenditure of more than $3.25B to support malaria control and elimination [1]. Optimism is elevated across sub-Saharan Africa by the roll-out of two partially effective malaria vaccines, RTS,S/AS01E and R21/Matrix M, both adjuvanted circumsporozoite protein (CSP) sub-unit vaccines indicated for use in infants and young children to reduce malaria-related morbidity and mortality [2]. The first 24 months of the RTS,S/AS01E pilot implementation programme in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi achieved a 32% reduction (95% CI 5–51%) in hospital admissions with severe malaria and a 9% reduction (95% CI 0–18%) in all-cause mortality excluding injury [3]. Neither vaccine has demonstrated benefit in older individuals in large field studies or meaningfully prevented malaria infection (as opposed to clinical disease) in endemic areas [4]. As a result, the WHO has called for the development of improved vaccines with at least 90% efficacy against infection in individuals across all age strata, to strengthen protection in malaria risk groups and to support mass vaccination programmes (MVPs) for regional malaria elimination [5].

PfSPZ Vaccine, composed of aseptic, purified, live (metabolically active), cryopreserved, radiation-attenuated, non-replicating Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites (PfSPZ), is a first-generation product based on whole PfSPZ [6] (P. falciparum NF54 strain) with the potential to address WHO’s call for a high efficacy vaccine more effectively than the adjuvanted protein subunit approach. It includes thousands of parasite proteins, compared to the single protein contained by RTS,S and R21. PfSPZ Vaccine has provided 100% vaccine efficacy (VE) against controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) in malaria-naive [7] and malaria-experienced [8] adults and has also provided durable VE against naturally transmitted P. falciparum infection in four field trials, with protection lasting from 6 to 21 months without booster doses of vaccine over one or two transmission seasons in adults in Mali and Burkina Faso [9–12]. This first-generation vaccine and a third-generation vaccine using the PfSPZ platform with two genes deleted to achieve attenuation, called PfSPZ-LARC2 Vaccine [6, 13], have been developed to meet the objectives of the WHO [5].

Safety and tolerability are key requirements when MVPs are planned across the age spectrum. Ideally, a vaccine would be sufficiently safe for use in pregnancy or in individuals with chronic medical or immunosuppressive conditions without a requirement to screen and exclude. To date, based on follow-up of 6,538 doses of PfSPZ Vaccine administered to 2,046 individuals 5-months to 61 years of age (including HIV-infected adults), constituting over 6 billion sporozoites injected, there have been no breakthrough blood stage infections, indicating that the intrinsic attenuation resulting from radiation is robust even in immunocompromised individuals [6]. Additional safety and tolerability data are available from 14 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) using doses ranging from 1.35 × 105 to 2.7 × 106 PfSPZ, including 3 trials in African infants [8–12, 14–23]. Normal saline was selected as the placebo in these RCTs because it can be safely administered by direct venous inoculation (DVI), the preferred route of administration for PfSPZ, and does not cause any systemic adverse events (AEs), providing a sensitive comparator to differentiate AEs caused by PfSPZ Vaccine from background rates. With the exception of myalgia in one study of African adults [11], there have been no differences in the frequency of AEs or laboratory abnormalities between PfSPZ Vaccine and normal saline recipients. Given the variety of AEs solicited in each trial, the myalgia excess in this one study may be a chance result. Taken together, these data indicate that the various regimens of PfSPZ Vaccine assessed in RCTs have few significant side effects, consistent with the “stealth biology” of sporozoites and liver stage parasites, which induce no symptoms or signs of disease in the human host [24].

Twelve of the 14 RCTs of PfSPZ Vaccine tested long interval regimens with 4 to 8 weeks between doses. More recently, regimens for this vaccine have evolved into shorter, multi-dose prime approaches with two to four “staircase” priming injections over the first week to provide a strong initial immune stimulus, followed by a boost [21, 22, 25]. One of the two RTCs assessing these more efficient regimens was in Malian women of child-bearing potential (WOCBP). The trial tested a condensed, days 1, 8 and 29 multi-dose prime and boost regimen of 9.0 × 105 or 1.8 × 106 PfSPZ per dose administered by DVI. This regimen significantly protected women against P. falciparum infection and clinical malaria over two transmission seasons with a VE of 61% in the second year against P. falciparum infection for the lower dose without an intervening boost. PfSPZ Vaccine also reduced the incidence of P. falciparum infection during subsequent pregnancies (VE 49–57%) and, in the group of women who became pregnant during the first six months of follow-up, achieved VE against P. falciparum infection of 65–86% [12]. In the same trial, there were no differences in the rates of solicited or unsolicited AEs or laboratory abnormalities compared with the normal saline controls. Based on these results, condensed, multi-dose prime regimens have been down-selected for further testing and development [6].

The other RCT that tested short interval regimens was the MAVACHE trial, conducted in malaria-naive German adults [22]. This trial measured protection using CHMI and assessed efficacy against both homologous strain (P. falciparum NF54) and heterologous strain (P. falciparum 7G8) parasites. PfSPZ were administered at doses ranging from 9.0 × 105 PfSPZ on days 1, 8 and 29 (n = 11) to 1.35 × 106 PfPSZ on days 1 and 8 (n = 6) to 2.7 × 106 PfSPZ on days 1 and 8 (n = 6). Vaccine efficacy (VE) at 3 and 9–10 weeks after last dose of the three-dose 9.0 × 105 regimen was 79% (95% PI: 54–95%) using a heterologous CHMI and 77% (95% PI:50–95%) using a homologous CHMI. The capacity to equally protect against heterologous and homologous CHMI, when VE against the former was previously significantly less [26], added to the appeal of the condensed regimen. In addition, the injections were well tolerated as in the Mali study, and there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of AEs between the vaccine and placebo groups. Noting that this small study lacked statistical power to discern minor differences, the clinical investigators reported systemic reactogenicity after the second dose in the two higher dose groups [22].

Based on this experience, two additional small trials have been performed to further assess the VE and tolerability of the down-selected multi-dose prime, condensed regimen (9.0 × 105 PfSPZ on days 1, 8 and 29) in malaria-naive adults, particularly because the stair-cased priming immunizations could be more reactogenic than long-interval regimens. One study, called Warfighter 3 (NCT04966871, unpublished) was conducted by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle (USSPZV6 trial) and the second, reported here (USSPZV7 trial), was conducted by the University of Maryland, Baltimore. This trial, although halted in midcourse due to a vial quality issue, administered two doses of PfSPZ Vaccine on days 1 and 8 to 30 adults before the study was closed, providing data on the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of the multi-dose prime portion of the regimen.

Methods

Aim, design and setting

USSPZV7 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Sanaria® PfSPZ Vaccine aiming to assess (1) the safety and tolerability of a three-dose, condensed (multi-dose prime) regimen and (2) VE against CHMI using a challenge parasite strain (P. falciparum 7G8) genetically and antigenically divergent (heterologous) to the vaccine strain (P. falciparum NF54). PfSPZ Vaccine is designed to induce sterile immunity, meaning that, when infectious PfSPZ are inoculated to initiate CHMI, the immune response induced by the vaccine kills the challenge PfSPZ and/or liver stages and no resultant blood stage infection occurs. Two cohorts of 30 individuals were to randomly receive PfSPZ Vaccine or normal saline placebo, with one cohort undergoing CHMI 3 weeks after immunization and another 12 weeks after immunization. Malaria-naive adults were selected as the study population to mimic non-exposed travelers, supporting Sanaria’s plan to initially license PfSPZ Vaccine to prevent P. falciparum malaria infection in travellers visiting malaria-endemic areas of Africa or other sites where P. falciparum is a significant risk. The two CHMI time points of 3 and 12 weeks were selected to mimic shorter and longer exposure periods, respectively, and to complement the 2-, 6- and 10-week CHMI time points assessed in the Warfighter 3 trial [NCT04966871].

Trial participants

The trial was performed at the clinical trial facility of the University of Maryland in Baltimore Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health (UMB). Healthy adults aged 18–50 years were recruited. Specific exclusion criteria included history of malaria infection in the preceding two years; history of cardiac disease, abnormal electrocardiogram or 5-year risk of cardiovascular event > 10% [27]; history of non-febrile or complex febrile seizures (simple febrile seizures in childhood allowed); laboratory evidence of HIV infection or active hepatitis B or C infection; current use of anti-malarial or immunosuppressive drugs; and evidence of other chronic illnesses or conditions. After written informed consent, volunteers were screened by medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria (see study protocol in Supplementary Material).

Intervention

PfSPZ Vaccine contains SPZ of the West African-derived P. falciparum NF54 strain [28]. The PfSPZ are administered without an adjuvant by DVI into a peripheral vein in the arm. CHMI is performed using a similar aseptic, purified PfSPZ product, Sanaria® PfSPZ Challenge (7G8), which is not attenuated by irradiation and is fully infectious. Plasmodium falciparum 7G8 is the clone of a parasite isolated in Brazil [29] and more divergent genetically and antigenically from P. falciparum NF54 than any P. falciparum parasites found in Africa, providing a stringent assessment of VE that in comparative studies gives a reasonable estimate of field efficacy in Africa [30]. The dose, 3.2 × 103 PfSPZ, also administered by DVI, has infected 53/54 (98.1%) adults undergoing first CHMI, including African adults with prior malaria exposure [22, 31–33]. PfSPZ Vaccine and PfSPZ Challenge (7G8) are initiated from strain-specific cell banks but otherwise are manufactured identically except for the radiation step for PfSPZ Vaccine. Both are cryopreserved and stored in liquid nitrogen vapour phase between −150 °C to −196 °C. Vials are thawed, diluted with phosphate buffered saline and human serum albumin to a volume of 0.5 mL, drawn into a 1 mL, low deadspace, syringe with integral 25G needle, and administered over a few seconds into a vein after demonstrating blood flashback (DVI procedure), within 30 min of vial thaw.

Randomization and blinding

On the day of first immunization (V1, administered on study Day 1), each participant invited to enroll, after medical clearance, underwent complete eligibility assessment. Eligible participants were assigned a participant identification and randomization number. The pharmaceutical operations team matched the randomization number to a master allocation list provided by the data management vendor (StatPlus, Taipei, Taiwan) to determine the treatment assignment and prepare the proper syringe for hand-off to the clinical team. Participants were randomized 3:1 to PfSPZ Vaccine or normal saline in each CHMI cohort using blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. PfSPZ Vaccine recipients were injected within 30 min of thaw. Participants were considered enrolled after study product receipt.

Syringes charged with PfSPZ Vaccine or normal saline are indistinguishable by appearance, odor, or consistency when injected, and cause no pain when the syringe plunger is pushed due to DVI administration and immediate dispersion of the injectate in the vasculature. The pharmaceutical operations team standardized syringe preparation time to prevent disparity regarding syringe preparation. The clinical team was restricted from entry into the pharmacy and the pharmaceutical operations team did not know the participants’ identities or interact with them, to support effective masking.

Immunization

Participants were scheduled for immunization on day 1 (V1), 8 (V2) and 29 (V3) with in-clinic follow-up on days 10 (V2 + 2 days), 15 (V2 + 7 days), 31 (V3 + 2 days) and 43 (V3 + 14 days) and a telephone interview on Day 38 (V3 + 7 days). Participants were asked to keep a diary (memory aid) where they recorded solicited symptoms daily from a specified list for seven days after each injection and any additional unsolicited symptoms for 28 days after each injection. The memory aids were reviewed during clinic visits and the symptoms graded for severity (mild, moderate, severe, depending on the impact on the activities of daily living), relatedness (unrelated or unlikely related considered unrelated, and definitely, probably and possibly related considered related), and duration (day of initiation and resolution). Medical history and medication use were reviewed at each in-clinic visit and vital signs and a focused physical examination performed. Laboratory testing, planned before V1, 7 days after V2, and 14 days after V3, consisted of white blood cell count, platelet count, haemoglobin, creatinine, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Urine βHCG was assessed on each vaccination day prior to immunization in female participants. Study physicians were available continuously to address any acute medical issues. COVID-19 testing was done when clinically indicated.

Controlled human malaria infection

Heterologous CHMI was planned for Day 50 (V3 + 21) and Day 113 (V3 + 84) for the two cohorts, respectively. Solicited symptoms post CHMI were scheduled for collection for seven days using a memory aid and reviewed in the clinic on Day CHMI + 7. In-clinic visits and daily reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to detect parasitaemia were schedule daily from Day CHMI + 7 to Day CHMI + 18, and then on days CHMI + 20, + 22, + 25 and + 28, with a final study visit on Day CHMI + 56. At each clinic visit, participants were to have vital signs measured and malaria signs and symptoms recorded. Participant treatment for malaria was planned after two positive qPCR results separated by greater than or equal to 12 h or a single qPCR result reading > 250 estimated parasites/mL. The first-line treatment regimen was atovaquone/proguanil one dose (1 gm/400 mg) on three consecutive days, with artemether/lumefantrine as back-up. Any participants not positive for malaria during CHMI follow-up would begin this same regimen on day CHMI + 28.

Data management, statistical analysis and sample size

Data were entered directly into an electronic database (StatPlus) and AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Version 25.1. Tolerability and safety data were described and tabulated without formal hypothesis testing. Categorical variables such as proportions of study groups experiencing AEs were summarized using absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies and were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation, median and range, and compared using the Mann–Whitney two-sided test. Efficacy was measured as [1 minus the risk ratio] × 100. The trial was designed to assess the null hypothesis that there was no significant difference in the proportion protected (no parasitaemia) between the vaccine groups combined and the placebo groups combined. Sample sizes of 45 and 15 for the vaccine and placebo groups were selected to show with 83% power, if there were six drop-outs from the vaccine groups and two from the control groups before CHMI, that an infection rate of 92.3% in the controls (12/13 developing parasitaemia) and 51% in the vaccinees (20/39 developing parasitaemia) was statistically significantly different (alpha = 0.05, 2-tailed), which is a VE of 44.4%. This provided a conservative power calculation because higher VE was expected.

Immunological studies

Immunogenicity was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to PfCSP using published procedures [34]. Serum was separated and frozen at −80 °C within 4 h of collection. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and M (IgM) antibody levels were reported as the serum dilution at which the optical density (OD) was 1.0 (OD 1.0), as well as the difference between post-vaccination OD 1.0 and pre-vaccination OD 1.0 (net OD 1.0). The ratio of post–OD 1.0 to pre–OD 1.0 (OD 1.0 ratio) was also calculated. An individual was considered to have seroconverted if the net OD 1.0 was ≥ 50 and the OD 1.0 ratio was ≥ 3.0. Fisher’s exact test was used to look for differences in seroconversion rates, the Mann–Whitney test for net OD 1.0 and OD 1.0 ratios, and nonparametric analysis of variance for comparing net OD and OD ratios between groups.

Trial oversight

The trial was approved and overseen by WCG IRB. A three-physician, independent Safety Monitoring Committee (SMC) monitored safety aspects of the trial with one member also serving as a local safety monitor to support the principal investigator in addressing any emerging clinical issues. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT05604521.

Results

Screening and immunizations

Fifty-seven individuals were screened in October and November 2022 and 51 met enrollment criteria as healthy adults. Thirty-one (18 males, 13 females) were selected based on availability to participate in the first cohort, slated to receive CHMI at 12 weeks after V3. Fifteen received V1 on 6 December and 16 on 8 December. This included 24 individuals receiving PfSPZ Vaccine and 7 receiving normal saline placebo. One participant, later identified as a PfSPZ Vaccine recipient, experienced shortness of breath, facial flushing, tachycardia and elevated blood pressure 6 min after her immunization which resolved within 2 min without intervention; this participant was not immunized a second time. The remaining 30 participants (18 males, 12 females) received V2 on 13 December 2022, a 7-day gap for 15 participants (11 individuals receiving PfSPZ Vaccine and 4 receiving normal saline) and a 5-day gap for 15 participants (12 individuals receiving PfSPZ Vaccine and 3 receiving normal saline). An additional 15 individuals were screened to complete the planned 3-week CHMI cohort. Altogether, 72 persons were screened, 31 received immunizations, 15 were screen failures, 4 were eligible but not enrolled, and 22 were being evaluated when the study was halted (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study Flow and Schema. * Two vaccinations required for inclusion in immunogenicity population

Participants and DVI

Randomization achieved reasonably balanced assignment to vaccine and placebo groups with respect to age, sex, ethnicity, race, and body mass index (Table S1). All immunizations were administered by DVI without difficulty using veins located in the antecubital fossa of the right or left arm, and no veins infiltrated during immunization.

Halting immunizations

At the time of V2 on 13 December 2022, a fiber was found by the pharmaceutical operations team in one vaccine vial during syringe preparation and the injection was not used. The FDA was notified the same day and placed the study on clinical hold on 15 December 2022. The study participants who were to receive V3 in early January 2023 were informed of the hold using an IRB-approved consent addendum (supplemental material). They were seen for a routine blood draw on December 19 or 20, 2022, for a follow-up safety visit and signing of the consent addendum on January 3 or 5, and for a final study visit on January 18 or 19, 2023 (Fig. 1).

Among the original objectives, there were two that could be partially addressed by the data collected before trial closure: (1) safety after a two-dose regimen; (2) antibody responses after a two-dose regimen. No CHMI data were obtained.

Safety

The safety population consisted of 31 individuals, 30 receiving two immunizations and 1 receiving one immunization. Twenty-four of the 31 received PfSPZ Vaccine (including the individual receiving one immunization) and 7 received normal saline. Solicited local AEs were collected for two days after each immunization. These were pain and pruritus (assessed by questioning the participant), tenderness and induration (assessed by palpation) and erythema, bruising and swelling (assessed by visual inspection). All local AEs were grade 1 in severity (less than 5 cm in diameter for most local AEs – see grading scales in supplementary material). A larger proportion of the placebo group experienced local solicited AEs (5/7, 71.4%) than the vaccine group (11/24, 45.8%) (Table 1), but no statistically significant differences were found. The most common local AE was bruising, occurring in 71% of controls and 30% of vaccine recipients, followed by erythema, occurring in 57% of controls and about 20% of vaccine recipients, with occasional pain, swelling and tenderness also reported in a few participants (Table S2).

Table 1.

Global Summary of Adverse Events (safety population)

| Parameter | PfSPZ Vaccine (N = 24) n (%) |

Normal Saline (N = 7) n (%) |

P value (Fisher's exact test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with at least 1 local solicited AE | 11 (45.83%) | 5 (71.43%) | 0.3944 |

| Participants with at least 1 local solicited Grade 2 AE | 0 | 0 | – |

| Participants with at least 1 local solicited Grade 3 AE | 0 | 0 | – |

| Participants with at least 1 systemic solicited AE | 14 (58.33%) | 6 (85.71%) | 0.3717 |

| Participants with at least 1 systemic solicited Grade 2 AE | 6 (25.00%) | 1 (14.29%) | 1.0000 |

| Participants with at least 1 systemic solicited Grade 3 AE | 0 | 0 | – |

| Participants with at least 1 unsolicited AE | 8 (33.33%) | 2 (28.57%) | 1.0000 |

| Participants with at least 1 unsolicited Grade 2 AE | 4 (16.67%) | 1 (14.29%) | 1.0000 |

| Participants with at least 1 unsolicited Grade 3 AE | 0 | 0 | – |

| Participants with at least 1 related unsolicited AE | 2 (8.33%) | 0 | 1.0000 |

| Participants with at least 1 related unsolicited Grade 2 AE | 2 (8.33%) | 0 | 1.0000 |

| Participants with at least 1 related unsolicited Grade 3 AE | 0 | 0 | – |

| Participants experiencing an SAE | 0 | 0 | – |

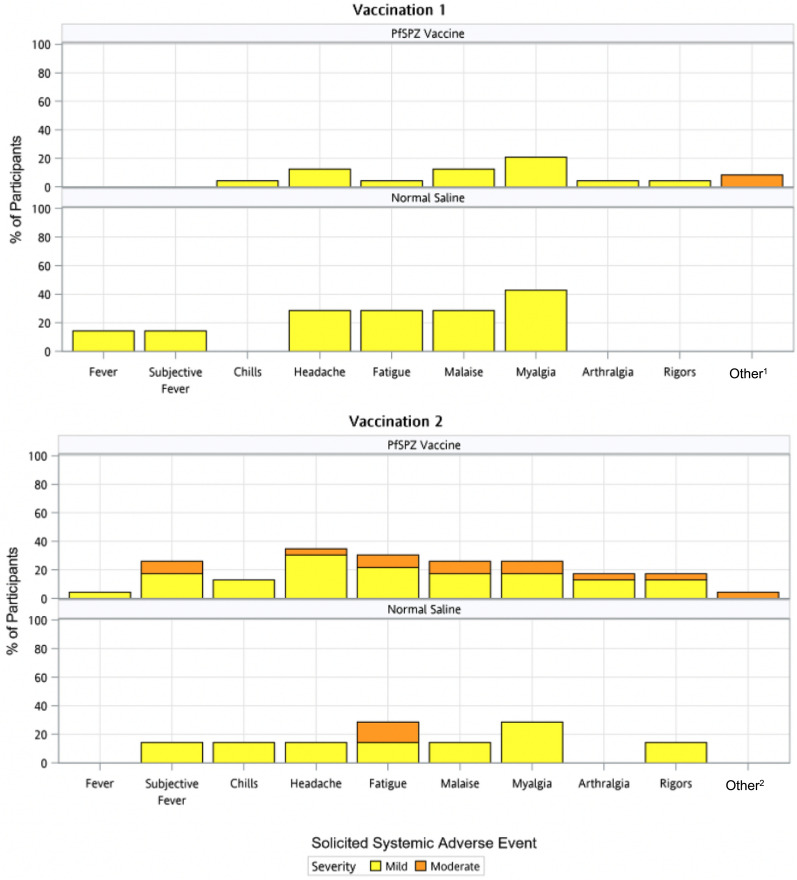

Solicited systemic AEs were collected for 7 days after each immunization. These consisted of fever (oral temperature > 100.4° F [38.0° C]), subjective fever, chills, headache, fatigue, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, rigors, or allergic type reactions (systemic rash, urticaria, pruritus, oedema). All but the last category were selected as “vaccine-typical” AEs (meaning AEs often caused by a variety of vaccines), and the last was directed at “vaccine-allergic” AEs. All solicited systemic AEs were grade 1 (mild) or grade 2 (moderate) in severity (not preventing daily activity – see grading scales in supplementary material). As with local AEs, a larger proportion of the placebo group experienced systemic AEs (6/7, 85.7%) than the vaccine group (14/24, 58.3%) (Table 1), but the difference was not statistically significant The most common individual AEs were headache, myalgia, fatigue, malaise and subjective fever, occurring in 16.7–33.3% of vaccine recipients and 28.6–57.1% of placebo recipients, respectively (lowest Fishers exact test p value was 0.3 for any comparison) (Fig. 2, Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Solicited Systemic Adverse Events. Systemic adverse events were solicited for 7 days after each vaccination and graded according to severity. There were no statistically significant differences between groups at either Vaccination 1 or Vaccination 2. 1Dermatographia in one participant, foot pruritus in a second; 2 Dematographia (continuing from V1)

Notably, four of 23 PfSPZ Vaccine recipients and one of seven normal saline recipients experienced one or more grade 2 symptoms during the first 24 h after V2 providing the blinded trial staff with a clinical impression of a vaccine reaction; these symptoms included headache, malaise, fatigue, subjective fever, rigors, arthralgia and myalgia, and there was additionally a grade 1 objective fever in one of the four participants. These grade 2 symptoms improved or resolved within 24 h. Three of these participants received V2 seven days after V1 (3/11 participants with this interval) and the fourth received V2 five days after V1 (1/12 participants with this interval) (Fishers exact test, p = 0.3, comparing the 5-day and 7-day interval groups). One normal saline recipient experienced grade 2 fatigue during the first 24 h after V2 (Fishers exact test, p = 1.0, comparing vaccine and placebo groups after V2). These grade 2 vaccine-typical AEs after V2 experienced by four vaccinees were striking because none of these (or any) vaccine recipients experienced, at grade 2 level, the same “vaccine-typical” AEs after V1 (Fig. 2). However, this difference did not achieve statistical significance when comparing the proportion of participants affected (Fishers exact test, p = 0.109).

Other types of AEs were observed after V1. One vaccine recipient experienced grade 2 dermatographia on days 2, 3, 4 and 5 after V1 (day 5 being the day of second vaccination for this participant) that was still present to some degree on the last study visit five weeks after V2, and another experienced grade 2 pruritus on both feet during the evening after V1, but not after V2. One vaccine recipient experienced the previously described episode of acute shortness of breath, elevated blood pressure, elevated heart rate and facial flushing two minutes after V1 with almost immediate resolution without treatment. The cause of this reaction was not determined, although an allergic reaction was deemed unlikely based on the rapid spontaneous resolution; a similar reaction has not been seen in any other study of PfSPZ products. This participant did not receive V2. Finally, there was one episode of grade 2 insomnia in a placebo recipient 3 days after V1, tallied as an unsolicited AE inasmuch as this symptom was not on the solicitation list.

There were 6 unsolicited AEs recorded outside the 7-day post-vaccination follow-up window for solicited AEs; all were viral infections deemed unrelated to the injections (Table S4). There were no serious adverse events (SAEs) recorded in the study (Table 1).

Laboratory testing was performed at baseline before V1, 7 days post V2 (as originally scheduled) and ~ 5 weeks post V2 (not originally scheduled). There was one elevation of white blood count in a single vaccinee at baseline and at the two time points post V2 considered not clinically significant (NCS); there were 3 depressions in haemoglobin level in vaccinees and 1 in a control participant post V2, all considered NCS; there was one elevation in platelet count in a vaccinee and one in a control participant post V2, both considered NCS; there were no elevations of creatinine post V2; there was one elevation in ALT in a vaccinee post V2, deemed NCS (Table S5). These laboratory abnormalities were all grade 1 in severity (see grading scales in supplementary material) and resolved.

Immunogenicity

The immunogenicity population consisted of the 30 individuals who received two immunizations. Two immunogenicity timepoints were assessed: pre-immunization, and 1 week after V2. Twenty-two out of 23 vaccine recipients seroconverted for both IgG and IgM, versus 0 out of 7 placebo recipients (Fisher’s exact test p < 0.001) (Table 2). The same vaccine participant did not seroconvert for IgM or IgG. Median net OD 1.0 antibody levels for vaccinees were 5,639 for IgG and 141,998 for IgM, and median OD 1.0 ratios were 97.5 for IgG and 1,060 for IgM (Fig. 3, Tables S6 and S7). The hypothesis was examined that there could be a relationship between reactogenicity and immunogenicity; the antibody levels of the four vaccine recipients who experienced grade 2 AEs after V2 were compared with those of the other vaccinees but were not significantly different, even in the most skewed instance (IgM Net OD) (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Seroconversion Rates after Two Immunizations (immunogenicity population)

| Investigational product administered by DVI on days 1 and 6 or days 1 and 8 | PfCSP IgG ELISA | PfCSP IgM ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Number positive/number tested (percent) | ||

| 9 × 105 PfSPZ of PfSPZ Vaccine | 22/23 (95.7%) | 22/23 (95.7%) |

| Normal saline | 0/7 | 0/7 |

Fig. 3.

Levels of Anti-CSP IgG and IgM Antibody by ELISA. Median and interquartile range of net OD 1.0 for IgG (Panel A) and IgM (Panel B) antibodies to PfCSP by ELISA 6 to 7 days after the 2nd dose of 9.0 × 105 PfSPZ of PfSPZ Vaccine or normal saline in malaria-naïve adults. Green datapoints signify the four participants with possible vaccine-induced Grade 2 adverse reactions after the second dose of PfSPZ Vaccine. P values were calculated by the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test. Panel C and Panel D are the same as A and B, but plot OD 1.0 ratios instead of net OD 1.0. In all four panels, OD 1.0 = reciprocal serum dilution at which the optical density was 1.0. In a separate assessment, the four vaccine recipients with moderately severe (grade 2) AEs (green datapoints) after V2 were compared to the other vaccine recipients (black datapoints) for the four immunologic indices, with p values as follows: IgG net OD: p = 0.73; IgG OD ratio: p = 0.19; IgM net OD: p = 0.07; IgM OD ratio: p = 0.16 – no statistically significant differences (Mann–Whitney test)

Discussion

The USSPZV7 trial was terminated after two doses of PfSPZ Vaccine were administered, due to a particulate issue that was traced to occasional particulates found in the vials provided by the vial vendor. Despite early study closure, the data generated after the two completed priming immunizations were analyzed to inform the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of a multidose prime approach. This effort was justified by prior findings that two priming doses of 9 × 105 PfSPZ of PfSPZ Vaccine on days 1 and 8 (followed by a booster dose on day 29) was safe and well tolerated and potentially more efficacious than three doses at 4-week intervals [12, 22]. This led to the down-selection of the condensed regimen for further development based on both logistical efficiency and improved VE. The potential benefit of stacked immunization is relevant to the general field of vaccinology, inasmuch as multi-dose priming has demonstrated benefit [35] and may be a useful option for vaccine clinical development.

In the first condensed regimen trial in Germany, called MAVACHE, the standard dose of 9 × 105 PfSPZ administered on days 1 and 8 did not cause any significant reactogenicity compared with placebo controls [22]. However, in a group receiving 1.35 × 106 PfSPZ on days 1 and 8, four of six participants had grade 1 systemic symptoms after the second (but not the first) immunization. Symptoms occurred approximately 10–12 h after administration on the same day as V2 in three volunteers and the next day in another volunteer, consisting of fever, chills, sweats and fatigue. One participant had additional grade 1 symptoms of diarrhea, arthralgia, myalgia and abdominal pain. All four participants experienced headache (grade 1 in two participants and grade 2 in two participants). Furthermore, in the group receiving 2.7 × 106 PfSPZ on days 1 and 8, 1/6 participants experienced grade 3 fever, chills, sweating, myalgia, fatigue and vomiting the evening of the day of V2, symptoms which lasted about a day. There was no statistically significant increase in these AEs after V2 versus V1, but the sample size of the study was small. This suggested that there was a need to further investigate the extent of reactogenicity after V2 versus V1, particularly in malaria-naive individuals.

In the USSPZV7 trial, during the first 24 h after V2, 4/23 (17.4%) vaccinees and 1/7 (14.3%) normal saline controls had AEs similar to those experienced by participants in the MAVACHE trial after higher dose PfSPZ Vaccine. These were “vaccine-typical” in that they were the same symptoms – headache, malaise, fatigue, subjective fever, chills, rigors, arthralgia and myalgia – as might occur after the administration of any vaccine; there was additionally an objective fever in one of the four participants. Of the grade 2 symptoms, the control participant experienced only fatigue. None of these symptoms attained grade 3, and all resolved quickly without treatment.

The reason for the superior protection induced by the day 1, 8 and 29 regimen in prior trials is not known [12, 21, 25], but it is hypothesized that the stacked V1 and V2 immunizations extend and amplify the initial antigenic stimulus, inducing more potent immunity. The multidose prime immunization on day 8, which introduces more immunogen into the inflammatory milieu induced by the first injection, could concurrently increase reactogenicity. These considerations are most relevant to a vaccine such as PfSPZ Vaccine, because damage from irradiation renders the parasites incapable of normal replication in the liver; there is no expanding antigen load, a problem not faced by live attenuated vaccines that replicate. Adding a second priming immunization may overcome this limitation of non-replicating whole organism vaccines but could result in adverse reactions in some recipients.

To assess a link between reactogenicity and improved vaccine response, correlations were sought between grade 2 reactogenicity and antibody levels after V2. Although no statistically significant difference in antibody levels was found in those with and without grade 2 reactogenicity, three of the four participants had anti-CSP IgM net OD antibody levels well above the median. This is not a definitive assessment, however, because antibody responses are not considered a primary mechanism of protection for PfSPZ Vaccine. Wheras antibody levels serve as a correlate of protection in some trials [9–12, 36], effector memory CD8 T cells residing in the liver likely mediate protection induced by PfSPZ Vaccine [37].

Interestingly, the condensed regimen has not caused adverse reactions in malaria-exposed adults, likely because of naturally acquired immunity. In the study in Malian women, 100 received a day 1, 8 and 29 regimen of 9.0 × 105 PfSPZ of PfSPZ Vaccine and 100 more received 1.8 × 106 PfSPZ on the same schedule. There were no differences in the rates of AEs between these women and those in a same-sized, placebo control group administered normal saline [12].

Antibody responses after two doses were similar to those seen in the MAVACHE trial. Figure 4 compares the two trials and includes data from MAVACHE on antibody levels after a third dose of 9.0 × 105 PfSPZ, as well after two doses of 1.35 × 106 PfSPZ and 2.7 × 106 PfSPZ. Adding the boosting dose on day 29 increases antibody levels compared with those induced by two doses, although tripling the dose to 2.7 × 106 PfSPZ per injection can achieve even greater levels after just two doses. As might be expected from what is known about antibody maturation, 1 week after the 2nd priming dose, the IgM responses to PfCSP were dramatically greater than were the IgG responses (Fig. 3 and Table S6).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of Antibody Levels in USSPZV7 and MAVACHE trials. Median and interquartile range of net OD 1.0 for IgG (Panel A) and IgM (Panel B) and OD 1.0 ratio for IgG (Panel C) and IgM (Panel D) antibodies to PfCSP by ELISA 6 to 7 days after the 2nd dose of 9.0 × 105 PfSPZ of PfSPZ Vaccine or normal saline in malaria-naïve adults. Levels and ratios were similar in the USSPZV7 and MAVACHE trials. A third vaccine dose in MAVACHE increased levels over two doses but not significantly. Two-dose regimens of higher doses also non-significantly increased levels

The insights that can be drawn from this trial are limited by the small sample size, which was half the planned number. This small sample size limited the ability to correlate vaccine reactogenicity to immunogenicity readouts. Similarly, because CHMI was not performed, efficacy was not assessed, and correlational analyses of reactogenicity or immunogenicity to protection could not be done.

In summary, PfSPZ Vaccine was safe and well tolerated overall. Laboratory tests 1 and 5 weeks after V2 did not show any abnormalities linked to immunization. The trial confirms PfSPZ Vaccine safety and immunogenicity in malaria-naive adults when administered in a condensed regimen, and supports ongoing clinical development, including testing in children. Future trials with larger sample sizes may better determine if adverse reactions occur after V2 in malaria-naïve vaccinees, an important consideration given the proposed traveller’s indication.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Joel V. Chua, who served as the local safety monitor and as a member of the Safety Monitoring Committee (SMC) along with John W. Sanders (chair) and Wesley W. Emmons. We additionally thank Annie Mo and other members of the NIH U44 grant team for their support of the study through a cooperative agreement.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- CHMI

Controlled human malaria infection

- CI

Confidence intervals

- COVID

Corona virus disease

- DVI

Direct venous inoculation

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HCG

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- IRB

Investigational review board

- LARC2

Late liver stage arresting, replication competent, 2 genes removed

- MAVACHE

Malaria vaccine of high efficacy

- MedDRA

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- MVP

Mass vaccination program

- NSC

Not clinically significant

- OD

Optical density

- PfCSP

Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein

- PfSPZ

Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SAE

Serious adverse event

- SMC

Safety review committee

- UMB

University of Maryland at Baltimore

- USSPZV6, 7

US-based sporozoite vaccine trial #6, #7

- V1

First vaccine dose

- V2

Second vaccine dose

- V3

Third vaccine dose

- VE

Vaccine efficacy

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WOCBP

Women of child-bearing potential

Author contributions

T.L.R., S.L.H and K.E.L.. conceived and designed the trial; A.A.B., M.B.L., C.B., S.J., A.R.K., L.B., and K.E.L. conducted the trial; T.L.R, L.W.P.C., N.K.C., M.C.C., Y.A., T.M., E.R.J. P.F.B., B.K.L.S., and S.L.H. provided sponsor oversight and clinical, regulatory, pharmaceutical operations, and immunological support; N.K.C. performed the immunology assays and analyses. T.L.R. analyzed the results. T.L.R., S.L.H. A.A.B., and K.E.L. wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This trial was funded by a U44 grant from NIAID (U44AI167783).

Data availability

The data supporting this study's findings are not openly available to protect participant confidentiality, but de-identified data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with adherence to human research protection guidelines.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical protocol was reviewed and approved by the WCG investigational review board.

Competing interests

T.L.R., L.W.P.C., N.K.C., M.C.C., Y.A., T.M., E.R.J. P.F.B., B.K.L.S., and S.L.H were salaried, full-time employees of Sanaria Inc at the time of this study. B.K.L.S. and S.L.H. own stock in Sanaria.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Andrea A. Berry and Thomas L. Richie contributed equally to this work.

Stephen L. Hoffman and Kirsten E. Lyke contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2023: tracking progress and gaps in the global response to malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

- 2.Hammershaimb EA, Berry AA. Pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines: RTS,S, R21, and beyond. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2024;23:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asante KP, Mathanga DP, Milligan P, Akech S, Oduro A, Mwapasa V, et al. Feasibility, safety, and impact of the RTS,S/AS01(E) malaria vaccine when implemented through national immunisation programmes: evaluation of cluster-randomised introduction of the vaccine in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. Lancet. 2024;403:1660–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polhemus ME, Remich SA, Ogutu BR, Waitumbi JN, Otieno L, Apollo S, et al. Evaluation of RTS,S/AS02A and RTS,S/AS01B in adults in a high malaria transmission area. PLoS ONE. 2009;4: e6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Malaria vaccines: preferred product characteristics and clinical development considerations. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2022.

- 6.Richie TL, Church LWP, Murshedkar T, Billingsley PF, James ER, Chen MC, et al. Sporozoite immunization: innovative translational science to support the fight against malaria. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2023;22:964–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seder RA, Chang LJ, Enama ME, Zephir KL, Sarwar UN, Gordon IJ, et al. Protection against malaria by intravenous immunization with a nonreplicating sporozoite vaccine. Science. 2013;341:1359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jongo SA, Church LWP, Mtoro AT, Chakravarty S, Ruben AJ, Swanson Ii PA, et al. Increase of dose associated with decrease in protection against controlled human malaria infection by PfSPZ Vaccine in Tanzanian adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2849–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sissoko MS, Healy SA, Katile A, Omaswa F, Zaidi I, Gabriel EE, et al. Safety and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum via direct venous inoculation in healthy malaria-exposed adults in Mali: a randomised, double-blind phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sissoko MS, Healy SA, Katile A, Zaidi I, Hu Z, Kamate B, et al. Safety and efficacy of a three-dose regimen of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite vaccine in adults during an intense malaria transmission season in Mali: a randomised, controlled phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:377–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirima SB, Ouedraogo A, Tiono AB, Kabore JM, Bougouma EC, Ouattara MS, et al. A randomized controlled trial showing safety and efficacy of a whole sporozoite vaccine against endemic malaria. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14:eabj3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Diawara H, Healy SA, Mwakingwe-Omari A, Issiaka D, Diallo A, Traore S, et al. Safety and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine against malaria in healthy adults and women anticipating pregnancy in Mali: two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 and 2 trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:1366–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goswami D, Patel H, Betz W, Armstrong J, Camargo N, Patil A, et al. A replication competent Plasmodium falciparum parasite completely attenuated by dual gene deletion. EMBO Mol Med. 2024;16:723–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jongo SA, Shekalage SA, Church LWP, Ruben AJ, Schindler T, Zenklusen I, et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and protective efficacy against controlled human malaria infection of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite vaccine in Tanzanian adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:338–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olotu A, Urbano V, Hamad A, Eka M, Chemba M, Nyakarungu E, et al. Advancing global health through development and clinical trials partnerships: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind assessment of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites vaccine for malaria in healthy Equatoguinean men. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:308–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jongo SA, Church LWP, Mtoro AT, Chakravarty S, Ruben AJ, Swanson PA, et al. Safety and differential antibody and t-cell responses to the Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite malaria vaccine, PfSPZ Vaccine, by age in Tanzanian adults, adolescents, children, and infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:1433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roestenberg M, Walk J, van der Boor SC, Langenberg MCC, Hoogerwerf MA, Janse JJ, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2a trial of the genetically attenuated malaria vaccine PfSPZ-GA1. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaaz5629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Steinhardt LC, Richie TL, Yego R, Akach D, Hamel MJ, Gutman JR, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of PfSPZ Vaccine administered by direct venous inoculation to infants and young children: findings from an age de-escalation, dose-escalation double-blinded randomized, controlled study in western Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oneko M, Steinhardt LC, Yego R, Wiegand RE, Swanson PA, Kc N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine against malaria in infants in western Kenya: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:1636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jongo SA, Urbano V, Church LWP, Olotu A, Manock SR, Schindler T, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of radiation-attenuated and chemo-attenuated PfSPZ vaccines in Equatoguinean adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104:283–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jongo SA, Church LWP, Nchama V, Hamad A, Chuquiyauri R, Kassim KR, et al. Multi-dose priming regimens of PfSPZ Vaccine: safety and efficacy against controlled human malaria infection in Equatoguinean adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;106:1215–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mordmüller B, Sulyok Z, Sulyok M, Molnar Z, Lalremruata A, Calle CL, et al. A PfSPZ vaccine immunization regimen equally protective against homologous and heterologous controlled human malaria infection. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongo SA, Urbano Nsue Ndong Nchama V, Church LWP, Olotu A, Manock SR, Schindler T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of radiation-attenuated PfSPZ Vaccine in Equatoguinean Infants, children, and adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;109:138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Vaughan AM, Aly AS, Kappe SH. Malaria parasite pre-erythrocytic stage infection: gliding and hiding. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyke KE, Singer A, Berry AA, Reyes S, Chakravarty S, James ER, et al. Multidose priming and delayed boosting improve Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite vaccine efficacy against heterologous P. falciparum controlled human malaria infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e2424–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein JE, Paolino KM, Richie TL, Sedegah M, Singer A, Ruben AJ, et al. Protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria by PfSPZ Vaccine. JCI Insight. 2017;2: e89154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaziano TA, Young CR, Fitzmaurice G, Atwood S, Gaziano JM. Laboratory-based versus non-laboratory-based method for assessment of cardiovascular disease risk: the NHANES I Follow-up Study cohort. Lancet. 2008;371:923–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delemarre BJ, van der Kaay HJ. [Tropical malaria contracted the natural way in the Netherlands](in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1979;123:1981–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkot TR, Williams JL, Schneider I. Infectivity to mosquitoes of Plasmodium falciparum clones grown in vitro from the same isolate. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:339–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva JC, Dwivedi A, Moser KA, Sissoko MS, Epstein JE, Healy SA, et al. Plasmodium falciparum 7G8 challenge provides conservative prediction of efficacy of PfNF54-based PfSPZ Vaccine in Africa. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurens MB, Berry AA, Travassos MA, Strauss K, Adams M, Shrestha B, et al. Dose-dependent infectivity of aseptic, purified, cryopreserved Plasmodium falciparum 7G8 sporozoites in malaria-naive adults. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:1962–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwakingwe-Omari A, Healy SA, Lane J, Cook DM, Kalhori S, Wyatt C, et al. Two chemoattenuated PfSPZ malaria vaccines induce sterile hepatic immunity. Nature. 2021;595:289–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sulyok Z, Fendel R, Eder B, Lorenz FR, KC N, Karnahl M, et al. Heterologous protection against malaria by a simple chemoattenuated PfSPZ vaccine regimen in a randomized trial. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mordmüller B, Surat G, Lagler H, Chakravarty S, Ishizuka AS, Lalremruata A, et al. Sterile protection against human malaria by chemoattenuated PfSPZ vaccine. Nature. 2017;542:445–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine MM, Ferreccio C, Black RE, Germanier R. Large-scale field trial of Ty21a live oral typhoid vaccine in enteric-coated capsule formulation. Lancet. 1987;1:1049–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishizuka AS, Lyke KE, DeZure A, Berry AA, Richie TL, Mendoza FH, et al. Protection against malaria at 1 year and immune correlates following PfSPZ vaccination. Nat Med. 2016;22:614–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss WR, Jiang CG. Protective CD8+ T lymphocytes in primates immunized with malaria sporozoites. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: e31247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are not openly available to protect participant confidentiality, but de-identified data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with adherence to human research protection guidelines.