Abstract

Background

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) in the care of persons living with HIV hinders the effectiveness of treatment strategies and undermines global health initiatives to achieve targets such as the 95-95-95 goals. Identifying risk factors for LTFU will help develop effective interventions that enhance long-term outcomes for people living with HIV (PLWHIV). Thus, this study aimed to explore the risk factors influencing LTFU among PLWHIV in a high-burden district in Ghana.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using medical records of 401 patients who initiated Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) between January 1st, 2011, and December 31st, 2021, in a high-burden district in Ghana and data extraction period of January to December 2022. We defined LTFU as a failure of a patient to return to the HIV clinic for at least 30, 90, 180, and 270 days from the date of their last appointment. A logistic regression model was utilized to determine the risk factors associated with LTFU.

Results

Out of 401 records reviewed, 298 (74%) were females. The proportions of individuals LTFU were 46%, 26%, and 15% for 90 days, 180 days, and 270 days, respectively. Additionally, only 14% of patients achieved the required four or more hospital visits within the last year of the review. Education was a risk factor associated with LTFU, with individuals with primary education (aOR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.66) and senior high school or higher education (aOR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.27, 0.99) having lower odds of LTFU compared to those with no education. The duration of HIV care was also associated with LTFU. Patients who were in care for less than or equal to five years were more likely to be LTFU compared to those in care for more than five years. None of the clinical variables were associated with loss to follow-up.

Conclusion

Our study provides new information about LTFU and its associated risk factors in Ghana. These findings underscore the need to promote health literacy in the fight against HIV/AIDS in Ghana.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-22254-w.

Keywords: Loss to Follow-Up, HIV, Antiretroviral drugs, Treatment outcomes

Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) pandemic continues to pose a significant global public health challenge, with an estimated 39.9 million people living with HIV (PLWHIV) worldwide and 630,000 AIDS-related deaths reported in 2023 [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Of these, an estimated 1.3 million cases were new HIV infections [2, 3, 5, 6]. In Africa, an estimated 26.1 million people were living with HIV in 2022. 86% of them were aware of their status, 77% were receiving treatment, and 72% were achieving suppressed viral loads [5, 6]. Ghana has one of the lowest prevalence rates in sub-Saharan Africa, with a prevalence rate of 1.8% [7]. However, previous studies in Ghana have revealed regional and geographical variations, with the highest prevalence reported in the Eastern, Western, Greater Accra, and Volta regions and the lowest in the three northern regions [7].

Improved antiretroviral therapy (ART) and broader healthcare initiatives have enhanced the quality of life for PLWHIV [1, 2, 4]. While ART is widely available, staying in care is essential for medication effectiveness, monitoring side effects, and preventing complications [3, 4, 8]. Current HIV management includes pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and ART [3, 9, 10]. However, successful HIV control requires more than medication alone - proper adherence and consistent medical care are crucial [2, 3, 5, 11, 12]. Proper adherence to ART is expected to improve patients’ quality of life [12]. While ART programs have expanded globally, many low- and middle-income countries face challenges with patients being lost to follow-up [13, 14].

For PLWHIV, discontinuing care compromises individual health and ART program success. Loss to follow-up (LTFU) refers to the discontinuation of ART care by patients for a minimum of three months for various reasons [15, 16]; others define LTFU as a discontinuation of treatment after 30 days [17], 60 days [18], or 365 days [19]. This disruption in care significantly impacts both individual outcomes and public health goals [11, 20]. Loss to follow-up continues to hinder treatment effectiveness [20] and impedes progress toward the 95-95-95 goals - which aim for 95% of PLWHIV to know their status, 95% of diagnosed individuals to receive sustained ART, and 95% of those on treatment to achieve viral suppression by 2030 [2, 5, 18].

Developing effective interventions to enhance long-term outcomes for PLWHIV necessitates understanding the risk factors associated with LTFU. Several studies have explored factors contributing to LTFU among HIV patients receiving ART in various, with multiple studies identifying distinct risk factors across different regions [15, 18, 19]. While the LTFU phenomenon is widespread, certain areas exhibit more pronounced factors contributing to this issue [14, 16, 21, 22, 23]. In East Africa, a Ugandan study identified several significant predictors, including rapid ART initiation (within 7 days of diagnosis), lack of telephone access, and advanced disease progression (WHO clinical stages 3 and 4) [21]. These findings align with broader regional studies that consistently highlight the impact of communication barriers and disease severity on retention in care [16]. In Southern Africa, particularly Namibia, research has revealed a different pattern of risk factors. Demographic characteristics such as younger age and male sex emerged as significant predictors of LTFU. Additionally, practical barriers, including work and domestic responsibilities, significantly impacted care retention. Treatment-related factors were also notable, with patients on efavirenz-based regimens showing higher LTFU rates [14]. Clinical indicators have emerged as consistent predictors across multiple regions. Advanced disease status (WHO stage IV) and compromised immune function (CD4 counts < 250 cells/ml) demonstrate strong associations with LTFU [22, 23]. The relationship between disease severity and LTFU appears particularly pronounced in resource-limited settings [16]. Sociodemographic and infrastructural factors also play crucial roles. Rural residence consistently emerges as a risk factor, often compounded by limited access to telecommunications [16]. In West Africa, studies from Ghana have identified unique cultural and religious factors, with religious affiliation (specifically the Muslim faith) showing a significant association with LTFU rates [23]. Hence, to comprehensively address barriers to the continuum of care for individuals living with HIV in a high-burden district of Ghana, it is important to identify and understand the local and country-specific challenges.

This study retrospectively analyzed data from January to December 2022 for patients who initiated ART between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021, in a high-burden area for HIV in Ghana. This study examined the risk factors influencing LTFU among PLWHIV in a high-burden district of the Eastern region of Ghana, aiming to provide valuable insights for developing targeted and relevant interventions. By offering a comprehensive analysis of LTFU risk factors in PLWHIV, this study seeks to bridge gaps in existing knowledge and inform not only individual-level interventions but also systemic changes. Its goal is to improve retention in care and individual health outcomes, as well as to aid in the development of implementation strategies to retain patients in care.

Methods

Study setting and design

The study was conducted at the Begoro District Hospital in the Fanteakwa District in the Eastern Region of Ghana, the district’s main hospital. The district’s economy is mainly rural and dominated by the agricultural sector, which employs about 75% of the population. The Begoro district hospital is the major health facility that serves a population of 56,987 residents from the surrounding communities [24]. The Fanteakwa district in Ghana has one of the country’s highest HIV infection rates, with an adult prevalence of 2.57% [7]. The data was extracted from the National AIDS/STI Control Programme (NACP) registries, specifically targeting people living with HIV (PLWHIV) aged 18 years and above and registered at the HIV clinic of the hospital. The hospital serves as a key healthcare facility for the region and had about 947 HIV-infected patients registered at the time of data extraction. Loss to follow-up rates after the sixth week of enrollment into HIV care in the Eastern Region stands at approximately 20.0% (Unpublished data). The hospital offers various services, including HIV counseling and testing, health education, and laboratory tests such as viral load assessments. There are three clinic days per week with an average attendance of 150 daily. Study participants who had registered at the HIV clinic between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2021, were included in the study. Data from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022, was extracted from the database to analyze lost to follow-up. The study protocol was approved by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) ethical review committee.

Study participants

Our study included all patients aged 18 years or older who tested positive for HIV, initiated antiretroviral therapy (ART) at any time between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021, and were to be followed up at the Begoro District Hospital. Participants were excluded if they had transferred out of care, if they were patients transferred from other HIV clinics, or if they had a history of prior ART, including individuals who had previously used post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). This exclusion was due to uncertainties in confirming their initial HIV test results and ART initiation dates.

Data sources and collection

The data of this study was obtained from the HIV clinic’s ART registers, as well as individual patient medical records. The registers, designed by NACP, follow standardized protocols for data collection and reporting. Information extracted from the ART registers encompassed the count of patients enrolled in care, dates of ART initiation, drug refill dates, CD4 count, baseline viral load, and WHO stage. Individual patient medical records, organized by recruitment year, codes, and patient outcomes, were maintained by the hospital in the clinic’s records office. The following information was extracted from each medical record:

Socio-demographic characteristics

This included age categories (13–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, ≥ 55 years), gender (male, female), religion (Christian, Muslim, others), education levels (no education, primary, junior high school, senior high school or higher), and marital status options (single, married, divorced, separated, widowed, cohabiting).

Clinical features

Data encompassed the Date of HIV diagnosis, HIV type (HIV type 1, HIV type 2, HIV type 1&2), WHO clinical stage (I, II, III, IV), Duration in HIV care (≤ 5 years, > 5 years) and Disclosure to partner status (yes, no).

Laboratory parameters

Baseline and follow-up measurements such as CD4 count (cells/µL), Viral load (categorized as detected/not detected; and ≤ 1000 copies/mL, > 1000 copies/mL).

The finalized dataset, consisting of relevant variables, was subsequently exported to Stata® software for comprehensive analysis.

Outcome measures

The two outcome measures are loss to Follow-Up (LTFU) and the number of hospital visits during the one-year follow-up period. Loss to follow-up was ascertained by classifying the time interval between their latest visit and the extraction date into discrete categories of 30, 90, 180, and 270 days. We defined LTFU by calculating intervals at 30, 90, 180, and 270 days (1, 3, 6, and 9 months, respectively) after a patient’s last clinic visit in the year of analysis. While downstream analysis focused on the 180-day (6-month) criterion, we examined multiple time intervals. The 180-day threshold is a widely supported approach in HIV research, minimizing misclassification of patients who may have temporarily missed appointments but remain engaged in care [5, 19, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Our downstream analysis used the 180-day threshold to provide a more robust assessment of true loss to follow-up [26]. Dates of the last hospital visit, and all hospital visits within the year of follow-up until December 31, 2022 [censorship date) were recorded. To ascertain the most recent clinic, visit date, and treatment registers were consulted. The duration between their most recent visit and the extraction date was computed, and the number of hospital visits during the one-year follow-up period was determined. For subsequent analysis, our study adopted a criterion of LTFU at 180 days, using a socio-economic framework to identify and assess risk factors associated with this outcome [26].

Data analysis

All data analyses were conducted using STATA version 17 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA). Participant characteristics were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Chi-squared (χ²) test was employed to examine categorical variables, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was utilized for dichotomous variables with non-normal distributions. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD), and their comparison was assessed using the independent samples t-test. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were employed to investigate factors associated with LTFU. During the univariable analysis, all variables were assessed. Subsequently, an initial model included all variables for the multivariable analysis, and backward elimination was applied. Variables were retained in the model if their p-value was ≤ 0.10 (Wald test).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Of the 947 PLWHIV initially identified as having started antiretroviral therapy (ART) at Begoro District Hospital between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021, the final analysis included 401 patients. We excluded patients transferred from other HIV clinics and those with prior ART history, including individuals who had previously used post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), due to uncertainties in confirming their initial HIV test results and ART initiation dates (59%). Differences between included and excluded participants are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The included and excluded groups showed significant differences in age distribution (p < 0.001) with the included group having higher proportions of participants aged 45 + years, and in HIV type (p < 0.001) where the included group had a notably higher percentage of HIV type 2 and dual infections (38.2% vs. 20.8%); there were also significant differences in WHO staging (p < 0.001), though both groups were similar in gender distribution, education, marital status, religion, viral load, and CD4 count. We extracted loss to follow-up (LTFU) information for the 401 participants from January–December 2022. Of these, 298 (74%) were females. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of people living with HIV who are 18 years and above in the Fanteakwa district of Ghana. The prevalence of LTFU for at least 6 months from January to December 2022 was about 26%. Our findings revealed significant differences in educational background and duration of care between groups. Education level was significantly different between those who were lost to follow-up and those who remained in care (p < 0.03), with a higher proportion of individuals who experienced LTFU having no education (35%) compared to those with primary (14%), junior high school (30%), or senior high school or higher education (22%). Additionally, LTFU was significantly more prevalent among patients with shorter HIV care duration (≤ 5 years) relative to those with longer care engagement (> 5 years). No statistically significant differences were observed in between LTFU and other demographic and health-related factors in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants by LTFU for at least 6 months

| Charcteristics | Not lost, n/N(%) | LTFU > = 6 months, n/N(%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 296 (73.82) | N = 105 (26.18) | ||

| Age Group (In Years)n/N(%) | 0.080 | ||

| 13–24 | 7/14 (50.0) | 7/14 (50.0) | |

| 25–34 | 53/78 (67.9) | 25/78 (32.1) | |

| 35–44 | 82/107 (76.6) | 25/107 (23.4) | |

| 45–54 | 79/109 (72.5) | 30/109 (27.5) | |

| =>55 | 72/89 (80.9) | 17/89 (19.1) | |

| Marital status, n/N(%) | 0.988 | ||

| Single | 43/56 (76.8) | 13/56 (23.2) | |

| Married | 128/175 (73.1) | 47/175 (26.9) | |

| Divorced | 48/66 (72.7) | 18/66 (27.3) | |

| Separated | 13/18 (72.2) | 5/18 (27.8) | |

| Widow(er) | 35/48 (72.9) | 13/48 (27.1) | |

| Cohabiting | 24/31 (77.4) | 7/31 (22.6) | |

| Gender, n/N(%) | 0.196 | ||

| Male | 81/103 (78.6) | 22/103 (21.4) | |

| Female | 215/298 (72.1) | 83/298 (27.9) | |

| Education Background, n/N (%) | 0.003 | ||

| No Education | 72/112 (64.3) | 40/112 (35.7) | |

| Primary | 77/89 (86.5) | 12/89 (13.5) | |

| Junior High School | 76/109 (69.7) | 33/109 (30.3) | |

| Senior High School or higher | 63/81 (77.8) | 18/81 (22.2) | |

| Religion, n/N(%) | 0.307 | ||

| Muslim | 13/17 (76.5) | 4/17 (23.5) | |

| Christian | 268/363 (73.8) | 95/363 (26.2) | |

| Others | 4/8 (50.0) | 4/8 (50.0) | |

| HIV Type, n/N(%) | 0.447 | ||

| HIV type1 | 150/199 (75.4) | 49/199 (24.6) | |

| HIV type2 + HIV type 1&2 | 88/123 (71.5) | 35/123 (28.5) | |

| Disclosure to partner, n/N(%) | 0.362 | ||

| No | 128/170 (75.3) | 42/170 (24.7) | |

| Yes | 33/48 (68.8) | 15/48 (31.2) | |

| WHO stage, n/N(%) | 0.856 | ||

| I | 103/144 (71.5) | 41/144 (28.5) | |

| II | 80/109 (73.4) | 29/109 (26.6) | |

| III | 88/116 (75.9) | 28/116 (24.1) | |

| IV | 23/30 (76.7) | 7/30 (23.3) | |

| Baseline viral load, n/N(%) | 0.290 | ||

| Not detected | 81/98 (82.7) | 17/98 (17.3) | |

| Detected | 100/130 (76.9) | 30/130 (23.1) | |

| Baseline viral load1[i], n/N (%) | 0.096 | ||

| >1000 | 50/60 (83.3) | 10/60 (16.7) | |

| <=1000 | 71/99 (71.7) | 28/99 (28.3) | |

| Duration in HIV care, n/N (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 5yrs and below | 179/264 (67.8) | 85/264 (32.2) | |

| >5yrs | 117/137 (85.4) | 20/137 (14.6) | |

| CD4 Count, Mean ± SD | 269.37 ± 277.13 | 326.90 ± 366.64 | 0.198 |

Baseline viral load is the viral load 6 months after initiation to HIV care. This was categorized as not detected and detected, and > 1000/<=1000

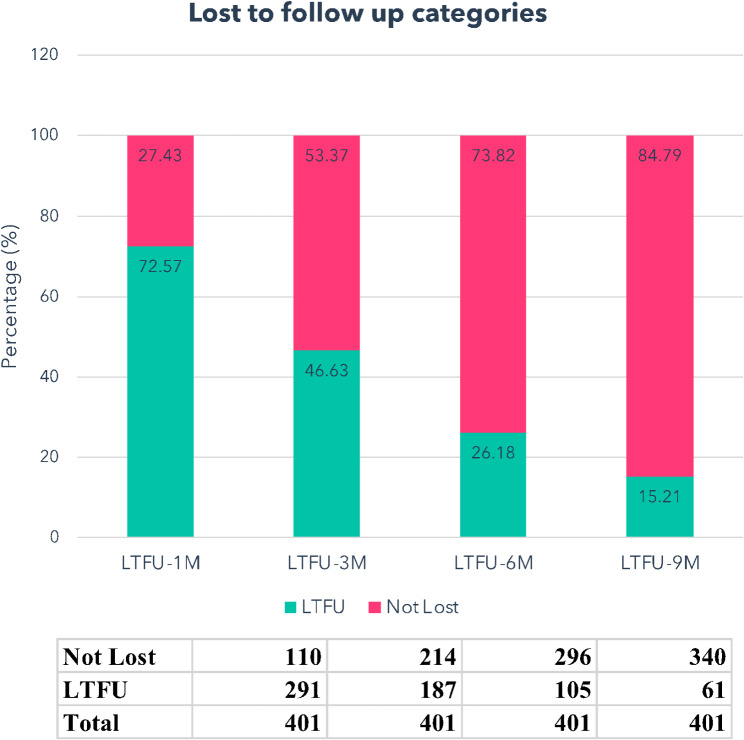

Loss to Follow-up

In total, 105 out of 401 patients (26%) were categorized as LTFU upon status assessment, using a criterion of at least 180 days (6 months) since their last visit. When applying the 270-day (9 months) criterion, the participant identified as LTFU was 15% (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

The proportion of patients loss to follow-up. This was categorized based on the number days since their last visit to the HIV clinic at the Begoro District Hospital. Over a 180-day period, 15.21% of patients did not attend clinic at all and were loss to follow-up

Furthermore, we evaluated the total count of visits within the one-year study period. Notably, only a minority of patients (14%) achieved the stipulated requirement of four or more hospital visits in a year (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The proportion of patients of meeting the required number visits within a year of data censoring. The number of patient visits to the HIV/ART clinic was recorded over one year. Only 13.5% of patients attended the required minimum of 4 visits annually

Variables associated with being loss to follow-up in patients attending clinics for the treatment of HIV infection in Ghana

In Table 2, we present a comprehensive analysis of participant characteristics and their statistical associations with LTFU, quantified through unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios. We observed statistically significant associations between educational background, age, and duration in care with loss to LTFU for at least 6 months (p = 0.005). Compared to participants aged 18–24 years, those aged 25–44 years (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.10–0.95) and ≥ 55 years (OR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.10–0.76) demonstrated significantly lower odds of LTFU.

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with loss to follow-up at least 6 months

| Characteristics | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group (In Years) | ||||

| 13–24 | ref | |||

| 25–34 | 0.47 (0.15, 1.49) | 0.201 | 0.56 (0.17, 1.83) | 0.336 |

| 35–44 | 0.30 (0.10, 0.95) | 0.041 | 0.49 (0.15, 1.60) | 0.240 |

| 45–54 | 0.38 (0.12, 1.17) | 0.093 | 0.64 (0.20, 2.07) | 0.452 |

| =>55 | 0.24 (0.10, 0.76) | 0.016 | 0.39 (0.12, 1.33) | 0.132 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | ref | |||

| Married | 1.21 (0.60, 2.46) | 0.589 | ||

| Divorced | 1.24 (0.54, 2.83) | 0.608 | ||

| Separated | 1.27 (0.38, 4.24) | 0.695 | ||

| Widow(er) | 1.23 (0.51, 2.99) | 0.650 | ||

| Cohabiting | 0.96 (0.34, 2.75) | 0.946 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | ref | |||

| Female | 1.42 (0.83, 2.43) | 0.198 | ||

| Education Background | ||||

| No Education | ref | ref | ||

| Primary | 0.28 (0.14, 0.58) | 0.001 | 0.32 (0.15, 0.66) | 0.002 |

| JHS | 0.78 (0.45, 1.37) | 0.390 | 0.78 (0.45, 1.37) | 0.518 |

| SHS or higher | 0.51 (0.27, 0.99) | 0.045 | 0.51 (0.27, 0.99) | 0.046 |

| Religion | ||||

| Muslim | ref | |||

| Christian | 1.15 (0.37, 3.62) | 0.809 | ||

| Others | 3.25 (0.55, 19.3) | 0.195 | ||

| Duration in HIV care | ||||

| 5yrs and below | ref | ref | ||

| >5yrs | 0.36 (0.21, 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.22, 0.69) | < 0.001 |

| HIV Type, n(%) | ||||

| HIV type1 | ref | |||

| HIV type2 + HIV type 1&2 | 1.22 (0.73, 2.02) | 0.447 | ||

| Disclosure to partner | ||||

| No | ref | |||

| Yes | 1.39 (0.69, 2.80) | 0.363 | ||

| WHO stage | ||||

| I | ref | |||

| II | 0.91 (0.52, 1.59) | 0.742 | ||

| III | 0.80 (0.46, 1.40) | 0.432 | ||

| IV | 0.76 (0.30, 1.92) | 0.568 | ||

| Baseline viral load | ||||

| >1000 | ref | 0.291 | ||

| <=1000 | 1.43 (0.74, 2.77) | |||

| CD4 Count, Mean ± SD | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.201 | ||

Bold p-values mean p < 0.05: Significant associations(p-value)

Participants with primary education (OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.14–0.58) and those with senior high school or higher education (OR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.27–0.99) exhibited reduced LTFU odds compared to individuals without formal education. Additionally, patients who had been in HIV care for more than 5 years showed decreased LTFU odds (OR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.21–0.62). After adjusting for potential confounding variables in a multivariate analysis, only education level and duration in HIV care demonstrated statistically significant associations with LTFU. Specifically, participants with primary education (OR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.15–0.66) exhibited significantly reduced LTFU odds compared to individuals without formal education. Moreover, patients who had been in HIV care for more than 5 years showed markedly decreased LTFU odds (OR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.22–0.69).

Discussion

In Ghana, the HIV care continuum remains a crucial component of the national response to HIV [2]. Despite progress in antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage, a substantial proportion of people living with HIV (PWHIV) are loss to follow-up (LTFU). This compromises their health outcomes and increases the risks of transmission [2, 4, 20]. This study examined the demographic characteristics and clinical factors contributing to LTFU among PLWHIV in a high-burden district in Ghana. Our study recorded 46%, 26%, and 15% of LTFU for at least 90 days, 180 days, and 270 days respectively. In addition, only 14% of patients achieved the required four or more hospital visits within the last year of review. Regarding risk factors, education level and duration of care were the only significant factors associated with LTFU. None of the clinical variables were associated with LTFU in the high-burden district in Ghana.

Loss to follow-up remains a critical public health challenge in high-HIV-burden regions, with significant implications for patient outcomes, including increased morbidity, mortality, hospitalizations, and the development of drug resistance [3, 6, 8, 20, 29, 30]. While the definition of LTFU varies across studies, with the World Health Organization recommending a 90-day interval and many studies traditionally using this timeframe [14, 21, 22, 23, 27, 28, 31, 32], our research adopted a 180-day criterion. This criterion is supported by evidence demonstrating its superiority in minimizing patient misclassification [25, 26]. Analysis from 111 health facilities across Africa, Asia, and Latin America also confirmed that longer intervals reduce misclassification risks, particularly for patients with extended ART dosing schedules who may adhere to treatment but have less frequent healthcare facility visits [26, 33]. This approach not only provides a more accurate assessment of true treatment disengagement but also helps identify patients requiring targeted re-engagement strategies, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of HIV treatment programs.

Our study’s definition of LTFU using the 180-day criterion aligns with previous research conducted in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Uganda [19, 25, 27, 34]. The LTFU rate observed in our study (26%) was comparable to findings from South Africa (23%) [27] but higher than rates reported in Ethiopia and Uganda [26, 35]. Notably, our findings from a high-burden district in Ghana approximate those from South Africa, a country with a significant HIV burden. This variation in LTFU rates between our study and those from Ethiopia and Uganda may be attributed to methodological differences, as their research encompassed multiple sites compared to our single high-burden district focus [19, 25]. Despite these methodological variations, all studies emphasize the critical importance of monitoring and addressing LTFU in HIV care programs [19, 25]. While most studies evaluate either LTFU rates [21, 25, 31, 32] or the frequency of hospital visits [36, 37] in HIV care programs, our study uniquely incorporates both measures. This dual approach provides a more comprehensive assessment of patient engagement, which is particularly valuable given the trend toward longer dosing periods under differentiated service delivery (DSD). It helps distinguish between true care discontinuation and reduced visit frequency due to extended prescription schedules [38].

Our analysis of LTFU risk factors revealed educational level as the sole significant predictor, while clinical factors showed no significant associations. This finding partially aligns with broader literature, where education consistently emerges as a key determinant of HIV care retention across multiple African settings [12, 16, 21, 23, 29, 38]. While studies in Ghana [23, 29], Tanzania [38], Ethiopia [16], and Uganda [21] have identified additional risk factors - including age, rural residence, CD4 count, religious affiliation, and clinical parameters - the predominance of education level in our findings underscores its fundamental role in health literacy and treatment adherence. The variation in risk factors across studies highlights the context-specific nature of LTFU determinants, suggesting a need for locally tailored retention interventions that particularly support patients with limited educational backgrounds. Loss to follow-up was markedly more prevalent among patients with shorter HIV care duration (≤ 5 years) relative to those with longer care engagement (> 5 years). This finding aligns with studies that identify the early years of HIV care as a critical period for retention interventions (15, 16, 18, 34]. The higher LTFU rates in patients with shorter care duration may reflect several underlying factors: initial challenges in adapting to care routines, incomplete treatment literacy, unresolved stigma concerns, and early experiences with medication side effects. Additionally, patients who have maintained care beyond five years may represent a self-selected group who have successfully navigated initial barriers to retention and developed robust support systems [15, 16, 18, 34].

This study provides insights into loss to LTFU among HIV patients in Ghana but has limitations. First, the analysis was limited to one high-burden district, affecting the generalizability to regions with different healthcare systems. While this focus provided detail on LTFU patterns, multi-site studies would better capture regional variations. Secondly, the small sample size may have reduced our ability to detect associations between risk factors and LTFU, with some factors not appearing significant. Thirdly, potential misclassification bias exists; patients labeled as LTFU may have transferred, died, or temporarily disrupted care. In addition, the systematic differences between included and excluded participants, particularly in age distribution and WHO staging, could have influenced our findings regarding the association (or lack thereof) between these variables and loss to follow-up (LTFU). The excluded group contained a higher proportion of younger individuals and those with WHO stage III disease, potentially introducing selection bias that may have affected the robustness of these specific associations in our analysis. Without proper tracking systems, LTFU rates could be inflated. Fourthly, we were limited by the clinical records available, missing variables like distance to the clinic, transport costs, stigma, social support, treatment regimens, and mental health. Future research should include larger, multi-site studies with improved tracking, comprehensive data sets, and standardized definitions of LTFU to produce stronger evidence for targeted retention interventions.

Conclusion

Our study sheds light on LTFU and its associated risk factors among adults living with HIV in Ghana, showing gaps in HIV care management. By underscoring the importance of health literacy, our study highlights the need of targeted programs to equip PLWHIV with the understanding and capacities associated with HIV care to minimize LFTU and improve the health indicators in the dynamics of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Ghana.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance accorded to us in the data collection and management by all healthcare workers and their leadership working at the Begoro District Hospital, in the Fanteakwa District of Ghana. We also want to thank the National AIDS/STI Control Programme for permitting us to use the data for this analysis.

Abbreviations

- LTFU

Loss to follow-up

- ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

- HIV/AIDS

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- PLWHIV

People Living With HIV

- QoL

Quality of Life

- PrEP

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

- PEP

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- NACP

National AIDS/STI Control Programme

- UNAIDS

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- WHO

World Health Organization

- GHS

Ghana Health Service

Author contributions

BAM: conceived the study design, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. DO, CA, MT, and EB were involved in the implementation and writing of the manuscript, and HEMB, GA, GB, and FDP were involved in the preparation and review of the manuscript. MW and EP were involved in the design, implementation, and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by the NIH Office for AIDS Research (OAR) FIC D43TW010540 grant and NIDA.

Data availability

The data used for this study is a de-identified dataset of individual-level routine HIV care and treatment data extracted from the National AIDS/STI Control Programme (NACP) registries. It is not currently publicly available as it is the property of the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Service. However, the dataset can be obtained from the corresponding author based on a reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research Institutional Review Board (NMIMR-IRB CPN 047/22–23) and the Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Board (GHS-ERC: 001/12/22). Since this study used secondary data, permission to access data was obtained from the Ghana National AIDS Control Programme and the two ethical review boards. Informed consent was not required because patients’ records were anonymized before access and each record was identified by a unique identity (ID) number. The study was conducted following the latest Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Michael Wilson and Elijah Paintsil contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bekker LG, Beyrer C, Mgodi N, Lewin SR, Delany-Moretlwe S, Taiwo B, et al. HIV infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Boakye DS, Adjorlolo S. Achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 treatment target by 2025 in Ghana: a myth or a reality? Glob Health Action. 2023;16(1):2271708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Frescura L, Godfrey-Faussett P, Feizzadeh AA, El-Sadr W, Syarif O, Ghys PD, et al. Achieving the 95 95 95 targets for all: A pathway to ending AIDS. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kumah E, Boakye DS, Boateng R, Agyei E. Advancing the Global Fight Against HIV/Aids: Strategies, Barriers, and the Road to Eradication. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.UNAIDS J. The path that ends AIDS: 2023 UNAIDS global AIDS update 2023 [cited 2024. Available from: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/8981354/the-path-that-ends-aids/9865836/

- 6.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet 2024 [cited 2025. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf

- 7.GAC. GHANA’S HIV FACT SHEET 2022. [Available from: https://citinewsroom.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2022_HIV_Estimates_Fact_Sheetfinal.pdf

- 8.Rachlis B, Bakoyannis G, Easterbrook P, Genberg B, Braithwaite RS, Cohen CR, et al. Facility-Level Factors Influencing Retention of Patients in HIV Care in East Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.WHO. Guideline on when to start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. 2015. [Available from: https://www.stiftung-gssg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2015_WHO_Guideline-on-when-to-start-antiretroviral-therapy.pdf [PubMed]

- 10.WHO. Person‑centered HIV patient monitoring and case surveillance 2017 [Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255702/9789241512633-eng.pdf

- 11.Vourli G, Katsarolis I, Pantazis N, Touloumi G. HIV continuum of care: expanding scope beyond a cross-sectional view to include time analysis: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Tsadik M, Berhane Y, Worku A, Terefe W. The magnitude of, and factors associated with, loss to follow-up among patients treated for sexually transmitted infections: a multilevel analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.HIV/AIDS. Understanding Fast-Track: accelerating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2015. [Available from: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/wh70tf3

- 14.Hong SY, Winston A, Mutenda N, Hamunime N, Roy T, Wanke C, et al. Predictors of loss to follow-up from HIV antiretroviral therapy in Namibia. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0266438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Berheto TM, Haile DB, Mohammed S. Predictors of Loss to follow-up in Patients Living with HIV/AIDS after Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(9):453-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Birhanu MY, Leshargie CT, Alebel A, Wagnew F, Siferih M, Gebre T, et al. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV-positive adults in northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Trop Med Health. 2020;48:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Gebremariam K, Tesfay F. Predictors of Loss to Follow Up of Patients Enrolled on Antiretroviral Therapy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research. 2014;5.

- 18.Dessalegn M, Tsadik M, Lemma H. Predictors of lost to follow up to antiretroviral therapy in primary public hospital of Wukro, Tigray, Ethiopia: a case control study. Journal of AIDS and HIV Research. 2015;7(1):1–9.

- 19.Melaku Z, Lamb MR, Wang C, Lulseged S, Gadisa T, Ahmed S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult Ethiopian patients enrolled in HIV care and treatment: a multi-clinic observational study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kebede HK, Mwanri L, Ward P, Gesesew HA. Predictors of lost to follow up from antiretroviral therapy among adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kiwanuka J, Mukulu Waila J, Muhindo Kahungu M, Kitonsa J, Kiwanuka N. Determinants of loss to follow-up among HIV positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a test and treat setting: A retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0217606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Mugglin C, Wandeler G, Estill J, Egger M, Bender N, Davies MA, et al. Retention in care of HIV-infected children from HIV test to start of antiretroviral therapy: systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sifa JS, Manortey S, Talboys S, Ansa GA, Houphouet EE. Risk factors for loss to follow-up in human immunodeficiency virus care in the Greater Accra Regional Hospital in Ghana: a retrospective cohort study. Int Health. 2019;11(6):605 − 12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Assembly FND. COMPOSITE BUDGET FOR 2019–2022 PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES FOR 2019 FANTEAKWA NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY 2019 [Available from: https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/composite-budget/2019/ER/Fanteakwa-North.pdf

- 25.Balde A, Lievre L, Maiga AI, Diallo F, Maiga IA, Costagliola D, et al. Risk factors for loss to follow-up, transfer or death among people living with HIV on their first antiretroviral therapy regimen in Mali. HIV Med. 2019;20(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, Newman JE, Zhou J, Cesar C, et al. Universal Definition of Loss to Follow-Up in HIV Treatment Programs: A Statistical Analysis of 111 Facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLOS Medicine. 2011;8(10):e1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Nelson F, Ganu V, Lambert F, Okine R, Puplampu P, Berko P. Challenges with Tracking Patients Living with HIV Lost to Follow Up in a Resource Limited Setting. Int J Sci Res in Multidisciplinary Studies Vol. 2020;6(11).

- 28.WHO. Consolidated guidelines on person-centred HIV patient monitoring and case surveillance 2017: WHO; 2017 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-151263-3

- 29.Kogi R, Krah T, Asampong E, Kamau EM. Factors affecting patients on antiretroviral therapy lost to follow up in Asunafo South District of Ahafo Region, Ghana: Cross-sectional Study. medRxiv. 2024:2024.01. 17.24301449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.WHO. Global HIV Programme 2024 [Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/overview

- 31.Seifu W, Ali W, Meresa B. Predictors of loss to follow up among adult clients attending antiretroviral treatment at Karamara general hospital, Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Wekesa P, McLigeyo A, Owuor K, Mwangi J, Ngugi E. Survival probability and factors associated with time to loss to follow-up and mortality among patients on antiretroviral treatment in central Kenya. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Balogun M, Meloni ST, Igwilo UU, Roberts A, Okafor I, Sekoni A, et al. Status of HIV-infected patients classified as lost to follow up from a large antiretroviral program in southwest Nigeria. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Mberi MN, Kuonza LR, Dube NM, Nattey C, Manda S, Summers R. Determinants of loss to follow-up in patients on antiretroviral treatment, South Africa, 2004–2012: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Ayisi Addo S, Abdulai M, Yawson A, Baddoo AN, Zhao J, Workneh N, et al. Availability of HIV services along the continuum of HIV testing, care and treatment in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ikhile O, Shah GH, Smallwood S, Waterfield KC, Nazaruk D. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Predicting Missed Clinic Visits among Patients Living with HIV on Antiretroviral Treatment in Kinshasa and Haut-Katanga Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Tarantino N, Brown LK, Whiteley L, Fernandez MI, Nichols SL, Harper G, et al. Correlates of missed clinic visits among youth living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2018;30(8):982-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Mushy SE, Mtisi E, Mboggo E, Mkawe S, Yahya-Malima KI, Ndega J, et al. Predictors of the observed high prevalence of loss to follow-up in ART-experienced adult PLHIV: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study in the Tanga Region, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study is a de-identified dataset of individual-level routine HIV care and treatment data extracted from the National AIDS/STI Control Programme (NACP) registries. It is not currently publicly available as it is the property of the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Service. However, the dataset can be obtained from the corresponding author based on a reasonable request.