Abstract

CONTEXT:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in 2019, causing the COVID-19 pandemic. While most infected people experienced mild illness, others progressed to severe disease, characterized by hyperinflammation and respiratory distress. There is still much to learn about the innate immune response to this virus. Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) is a transcription factor that is activated when pattern recognition receptors detect viruses. Upon activation, IRF3 induces the expression of interferon beta (IFN-β) and interferon-stimulated genes, which protect the host from viral infection. However, coronaviruses antagonize this pathway, delaying type 1 IFN production. It is, therefore, unclear how IRF3 influences COVID-19 disease. Our prior reports showed that IRF3 promotes harmful inflammation during bacterial sepsis in mice.

HYPOTHESIS:

We hypothesized that IRF3 cannot effectively control the SARS-CoV-2 viral load and instead promotes harmful inflammation during severe COVID-19.

METHODS AND MODELS:

We used mice transgenic for the human angiotensin converting-enzyme 2 transgene, driven by the keratin 18 promoter (K18-ACE2 mice) that were IRF3 deficient or IRF3 sufficient to test how IRF3 influences COVID-19 disease.

RESULTS:

Upon infection with SARS-CoV-2, K18-ACE2 mice showed a dose-dependent disease, characterized by mortality, lethargy, weight loss, and lung pathology, reminiscent of clinical COVID-19. However, K18-ACE2 mice lacking IRF3 were protected from severe disease with reduced mortality (84.6% vs. 100%) and disease score. We found that IRF3 promoted IFN-β production in the lungs and reprogrammed the cytokine profile, while viral load in the lungs was similar in the presence or absence of IRF3.

INTERPRETATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS:

These data indicated that IRF3 played a detrimental role in murine COVID-19 associated with changes in IFN-β and inflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: COVID-19, cytokines, interferon regulatory factor 3, interferons, human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice, K18-ACE2 mice

KEY POINTS

Question: This study used a mouse model to investigate how interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) influences COVID-19 disease.

Findings: Animals lacking IRF3 were protected from COVID-19 disease with reduced mortality and disease score. Their lungs showed an altered inflammatory profile but little difference in viremia.

Meaning: Our study demonstrates that IRF3 plays a detrimental role in COVID-19 disease in mice associated with altered inflammation rather than viremia.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection induces a range of disease phenotypes, from asymptomatic to severe acute respiratory infection, characteristic of COVID-19. During early infection, the virus triggers multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, TLR4, TLR7, TLR9, and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) (1–7). Several of these pathways are known to activate interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), a transcription factor that induces interferon (IFN)-β to suppress viral replication (8). SARS-CoV-2, however, manipulates this pathway, delaying IFN-β production (9–12). Therefore, it is unclear if IRF3 and IFN-β can effectively limit viral infection and how they influence the course of disease. We previously showed that that IRF3 promotes inflammation and lethal disease in mouse models of bacterial sepsis (13–17). We hypothesized that IRF3 may play a similar, detrimental role in COVID-19 disease, promoting inflammation and mortality. In this study, we recapitulated the K18-ACE2 mouse model of severe COVID-19 disease, and used IRF3-deficient mice to test how this transcription factor influenced the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19.

METHODS

This study used mice transgenic for the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, driven by the keratin 18 promoter (K18-ACE2 mice) and IRF3 knockout x K18-ACE2 mice. Experimental animals were 56.4% female, 43.6% male, and 24.27 ± 3.89 weeks old (mean ± sd). All experiments with SARS-CoV-2 were performed in Biosafety Level-3 containment. SARS-CoV-2 (USA-Washington State A1/2020 SARS-CoV-2 isolate) was propagated in Vero-E6 cells. Mice were anesthetized, and inoculated with 2.5 × 103, 2.5 × 104, or 2.5 × 105 plaque forming units (PFUs) of SARS-CoV-2, administered intranasally in 50 μL volume. Controls received 50 μL of saline solution. We monitored animal mortality for 14 days using humane endpoints, as well as weight and disease score (lethargy), per our prior reports (14–18). Additional mice were euthanized to collect lung lobes; these were homogenized and the infectivity titer was determined by plaque assay, per our prior report (19). We used LEGENDplex (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) bead immunoassays to measure cytokines in lung homogenates and standardized these to the protein content. Data were compared with nonparametric analyses, and validated with a nonparametric bootstrap t test (20). Furthermore, we determined the clustering between cytokine expression levels at day 2 using a variable cluster analysis (21). A p value of less than 5% was considered significant. For details, see Supplemental Methods (http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479).

RESULTS

We first recapitulated the K18-ACE2 mouse model of severe COVID-19 (22–26). K18-ACE2 mice were infected with 2.5 × 103, 2.5 × 104, and 2.5 × 105 PFU of SARS-CoV-2 or administered saline (controls). We observed dose-dependent animal mortality (Fig. S1A, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479), disease score (Fig S1B, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479) and weight loss (Fig. S1C, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479) in SARS-CoV-2-infected animals, while saline controls remained healthy. Lung histology revealed that SARS-CoV-2-infected mice had a remarkable perivascular inflammatory infiltrate predominated by lymphocytes and mononuclear leukocytes, as well as pulmonary edema at 2 days post-infection, similar to clinical COVID-19 (Fig. S1D, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479).

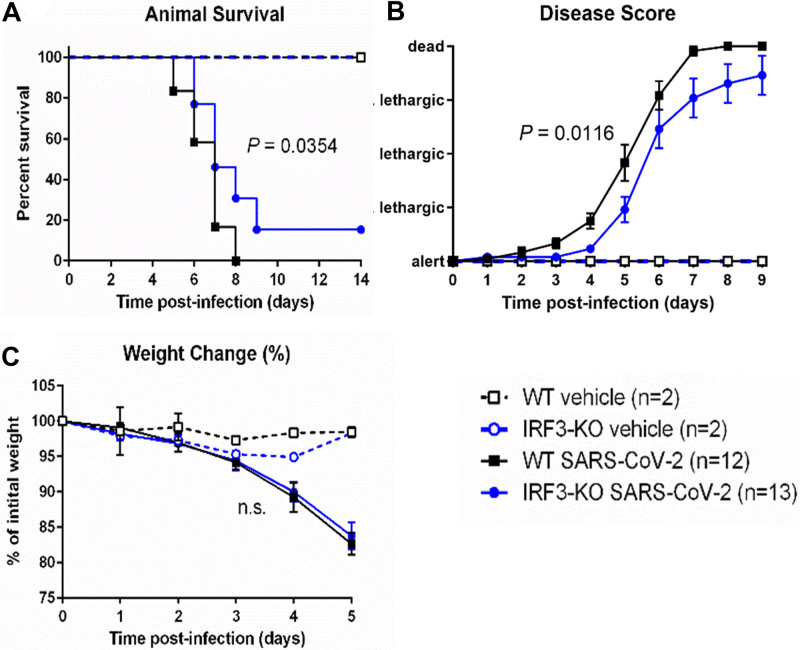

To investigate the impact of IRF3 on severe COVID-19 disease in this model, we crossed K18-ACE2 mice to IRF3 knockout mice and compared these animals to IRF3-sufficient K18-ACE2 mice (referred to hereafter as IRF3 knockout and wild-type mice, for brevity). Animals were challenged with 2.5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2 or saline (controls). We found that IRF3 knockout mice were protected from severe COVID-19 disease, exhibiting significantly reduced mortality rates (84.6%) vs. wild-type mice (100%; Fig. 1A). Additionally, IRF3 knockout mice showed a significantly attenuated disease score vs. wild-type mice (Fig. 1B). We observed a slight trend toward attenuated weight loss in IRF3 knockout vs. wild-type mice (Fig. 1C). Saline controls remained healthy.

Figure 1.

Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-knockout (KO) mice are protected from severe COVID-19 disease. IRF3-KO and wild-type (WT) mice (both carrying the human angiotensin converting-enzyme 2 transgene, driven by the keratin 18 promoter [K18-ACE2] ) were infected with 2.5 × 104 plaque forming units of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or saline vehicle as a control. Graphs show animal survival (A), animal disease score (B), and percent weight change (C), relative to the initial animal weight. p values show the results of a log-rank test (animal survival), and a two-way analysis of variance on the rank data, reflecting the group difference (for disease score and weight change). n.s. = not significant.

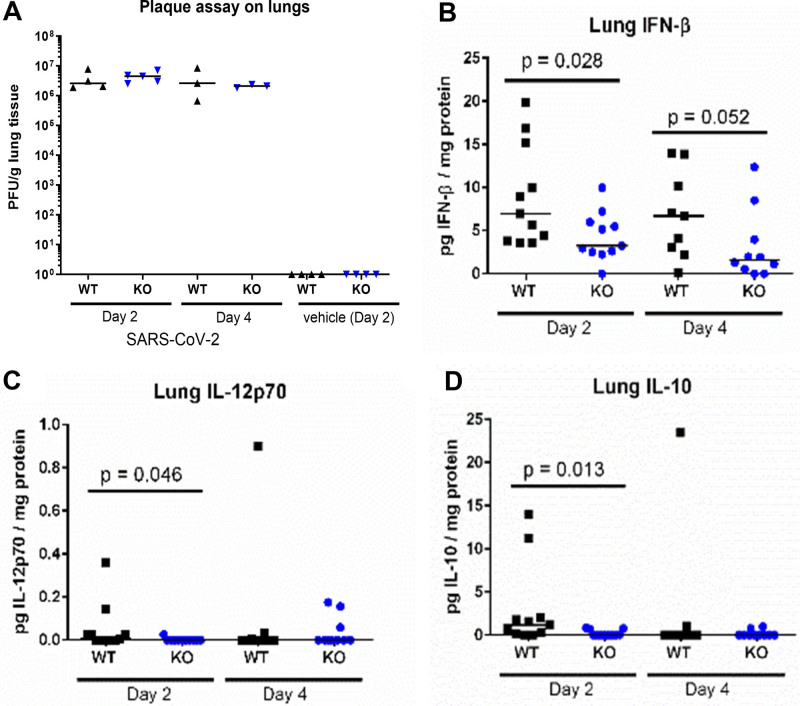

To determine the effect of IRF3 on viremia and cytokine production, we challenged additional cohorts of IRF3 knockout and wild-type mice with 2.5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2, and euthanized the animals to obtain lung homogenates at day 2 and day 4 post-infection. We observed a similar viral load in the lungs of wild-type vs. IRF3 knockout mice at both time points (Fig. 2A). Animals administered saline showed no viral plaques. We also measured cytokines in the lung homogenates. We found that IFN-β was significantly lower in the lungs of IRF3 knockout vs. wild-type mice at day 2 post-infection and also found lower levels (borderline significance) at day 4 post-infection (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the levels of interleukin (IL)-12p70 (Fig. 2C) and IL-10 (Fig. 2D) were significantly lower in IRF3 knockout vs. wild-type mice at day 2 post-infection. We also observed a trend toward lower levels of IL-1α, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-23, and IL-27 in IRF3 knockout vs. wild-type mice at day 2 post-infection and for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) at day 2 and day 4 post-infection (Fig. S2A–E, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479). The levels of IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)-9, CXCL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) showed minimal differences in wild-type vs. IRF3 knockout mice (Fig. S2F–M, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479). A bootstrap test supported these results (Fig. S4, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479).

Figure 2.

Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) alters the inflammatory cytokine profile in the lungs after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. IRF3-knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice (both carrying the human angiotensin converting-enzyme 2 transgene driven by the keratin 18 promoter [K18-ACE2]) were infected with 2.5 × 104 plaque forming units of SARS-CoV-2 or saline vehicle as a control. Cohorts of animals were euthanized and their lung lobes collected at day 2 and day 4. Graphs show the levels of viral load (A), normalized to lung weight, and interferon beta (IFN-β) (B), interleukin (IL)-12p70 (C), and IL-10 (D), normalized to protein content. Each point represents the individual value for a single mouse lung lobe, and the line indicates the median in each group. p values show the result of a Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

We next performed a clustering analysis of the inflammatory cytokines on day 2 to identify cytokines that were consistently grouped together based on their expression levels. We found four clusters among 16 cytokines, explaining 74% of the variability (Fig. S3, A and B, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479). Cluster 1 included CXCL-10, IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6, MCP-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1α explaining 43% of the variability; cluster 2 included GM-CSF, IL-10, IL-1β, and IL-12p70 explaining 15% of the variability; cluster 3 included CXCL-9 and IL-17A; and cluster 4 included IL-27 and IL-23. These results were confirmed with a bootstrap test (Fig. S4, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479).

DISCUSSION

PRRs play a key role in host defense against viruses through the induction of IFN-β. However, the inflammation induced by these pathways can damage host tissues. Our prior reports showed that IRF3 plays a detrimental role in mouse models of sepsis and systemic inflammation (13, 14, 16, 17). In this study, we recapitulated a mouse model of COVID-19 in K18-ACE2 mice. Mice developed lethal disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with dose-dependent mortality, lethargy and weight loss, and inflammatory lung pathology consistent with clinical severe COVID-19 (Fig. S1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479), consistent with reports by others (22–26). We next investigated if IRF3 affected COVID-19 disease in this model. IRF3 knockout mice carrying the K18-ACE2 transgene had improved survival and a lower disease score vs. wild-type mice (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate a novel, detrimental role for IRF3 in COVID-19 pathogenesis in mice, akin to its role in sepsis (14, 16, 17). Our study represents a new key finding demonstrating how innate immunity influences severe COVID-19 disease.

Regarding the upstream pathways that activate IRF3, prior studies determined that SARS-CoV-2 activates TLR2, TLR4, TLR7, TLR9, and RLRs (1–7). These pathways converge upon myeloid differentiation primary response 88, IRF3, and IRF7 to induce an innate immune response (8). Our data also suggest the downstream mechanism whereby IRF3 exacerbates severe COVID-19. The IRF3 knockout mice exhibited lower levels of IFN-β, IL-12p70, and IL-10 vs. their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2), and a trend toward lower levels of IL-1α, TNF-α, IL-23, IL-27, and GM-CSF (Fig. S2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479). Furthermore, cytokines were co-expressed in four distinct clusters based on a variable cluster analysis, suggesting hierarchical co-regulation by IRF3 (Fig. S3, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B479). We therefore predict that IRF3 exerts its effects by altering the cytokine network in a hierarchical fashion, and thereby promotes harmful inflammation, akin to its role in bacterial sepsis (17).

We observed a similar viral load in wild-type vs. IRF3 knockout mice (Fig. 2A), which may seem surprising given the classic role of IRF3 and IFN-β is to suppress viral infection. However, prior reports showed that SARS-CoV-2 manipulates IFN production, via cleavage of IRF3 and other mechanisms (9–12). We speculate that, due to manipulation of the host response by the virus, IFN-β is not avidly produced by infected cells. In contrast, we predict that once the viral load has built up, IRF3 becomes activated in noninfected cells that sense SARS-CoV-2 components, where the virus is unable to suppress IRF3 activation. Hence, IFN-β is produced at 2 days post-infection, at a time point that is too late to suppress viremia, and instead promotes harmful inflammation. This notion is consistent with a prior study in a nonlethal mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which found that mice lacking the receptor for type 1 interferons (IFNAR) or IRF3/7 showed little difference in viral load, and reduced inflammation in the lungs (27). Our results are consistent with this prior report and go further in showing the effects of IRF3 on animal mortality.

Our study may help to explain the mixed results of clinical trials that administered type 1 IFN to patients with COVID-19. An early clinical trial suggested that IFN-β could shorten the time to negative culture when administered to COVID-19 patients in combination with antiviral therapy (28). In another small randomized clinical trial, IFN-β did not change the time to clinical response; however, early administration of IFN-β reduced mortality (29). The subsequent Solidarity trial showed that IFN had little effect on mortality, ventilation, or length of hospital stay, when used alone or in combination with lopinavir (30). Also, in the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment trial, administration of IFN-β + remdesivir did not improve time to recovery vs. placebo + remdesivir (31). Furthermore, for patients who already required high-flow oxygen at enrollment, the group administered IFN-β had more serious adverse events vs. the placebo group (31). These clinical studies support the notion that IFN-β may exhibit both beneficial early effects and harmful late effects during COVID-19 disease.

CONCLUSIONS

This report showed that IRF3 plays a detrimental role in a mouse model of severe COVID-19. Further research is required to expand our understanding of the helpful and harmful effects of innate immunity on COVID-19 disease and reveal new therapeutic targets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the veterinarian and animal husbandry staff at the University of Texas at El Paso and the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso for their assistance.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Experimental studies were supported by a seed grant from the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso and the University of Texas at El Paso, awarded to Drs. Walker and Watts. Also, partial support for laboratory supplies was provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to the Border Biomedical Research Center (Award Number 3U54MD007592-27S1).

Drs. Walker and Dwivedi were supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Award Number R15HL159554). The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

This work represents a collaboration between all the authors. Dr. Walker conceived the study, designed and performed experiments, and analyzed data. Drs. Garcia, Palermo, and Goswami performed experiments and analyzed data. Dr. Hakim analyzed lung histology. Dr. Dwivedi performed statistical and data analysis. Dr. Watts contributed to the conception and experimental design, performed experiments, and analyzed data. Dr. Walker wrote the article with contributions from all authors.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

Contributor Information

Luiz F. Garcia, Email: luizf.garcia19@gmail.com.

Pedro M. Palermo, Email: ppalermo@utep.edu.

Nawar Hakim, Email: Nawar.Hakim@ttuhsc.edu.

Alok K. Dwivedi, Email: Alok.Dwivedi@ttuhsc.edu.

Douglas M. Watts, Email: dwatts2@utep.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, et al. : TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol 2021; 22:829–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Sluis RM, Cham LB, Gris-Oliver A, et al. : TLR2 and TLR7 mediate distinct immunopathological and antiviral plasmacytoid dendritic cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. EMBO J 2022; 41:e109622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung PS, Yang SP, Peng YC, et al. : CLEC5A and TLR2 are critical in SARS-CoV-2-induced NET formation and lung inflammation. J Biomed Sci 2022; 29:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Kuang M, Li J, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interacts with and activates TLR41. Cell Res 2021; 31:818–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa TJ, Potje SR, Fraga-Silva TFC, et al. : Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 activation contribute to SARS-CoV-2-induced endothelial cell damage. Vascul Pharmacol 2022; 142:106946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang DM, Geng TT, Harrison AG, et al. : Differential roles of RIG-I like receptors in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mil Med Res 2021; 8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hage A, Bharaj P, van Tol S, et al. : The RNA helicase DHX16 recognizes specific viral RNA to trigger RIG-I-dependent innate antiviral immunity. Cell Rep 2022; 38:110434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honda K, Taniguchi T: IRFs: Master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6:644–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gori Savellini G, Anichini G, Gandolfo C, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 N protein targets TRIM25-mediated RIG-I activation to suppress innate immunity. Viruses 2021; 13:1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng J, Zheng Y, Zheng SN, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 inhibits type I and III IFN production by targeting the RIG-I/MDA5, TRIF, and STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol 2023; 95:e28561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han L, Zhuang MW, Deng J, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b antagonizes type I and III interferons by targeting multiple components of the RIG-I/MDA-5-MAVS, TLR3-TRIF, and cGAS-STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol 2021; 93:5376–5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moustaqil M, Ollivier E, Chiu HP, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 proteases PLpro and 3CLpro cleave IRF3 and critical modulators of inflammatory pathways (NLRP12 and TAB1): Implications for disease presentation across species. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021; 10:178–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker WE, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR: TLR9 and IRF3 cooperate to induce a systemic inflammatory response in mice injected with liposome:DNA. Mol Ther 2010; 18:775–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker WE, Bozzi AT, Goldstein DR: IRF3 contributes to sepsis pathogenesis in the mouse cecal ligation and puncture model. J Leukoc Biol 2012; 92:1261–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heipertz EL, Harper J, Walker WE: STING and TRIF contribute to mouse sepsis, depending on severity of the disease model. Shock 2017; 47:621–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goswami DG, Walker WE: Aged IRF3-KO mice are protected from sepsis. J Inflamm Res 2021; 14:5757–5767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heipertz EL, Harper J, Goswami DG, et al. : IRF3 signaling within the mouse stroma influences sepsis pathogenesis. J Immunol 2021; 206:398–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goswami DG, Rubio AJ, Mata J, et al. : Large peritoneal macrophages and transitional premonocytes promote survival during abdominal sepsis. Immunohorizons 2021; 5:994–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palermo PM, Orbegozo J, Watts DM, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies in white-tailed deer from Texas. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2022; 22:62–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwivedi AK, Mallawaarachchi I, Alvarado LA: Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Stat Med 2017; 36:2187–2205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwivedi AK, Shukla R: Evidence-based statistical analysis and methods in biomedical research (SAMBR) checklists according to design features. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2020; 3:e1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler ES, Bailey AL, Kafai NM, et al. : SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat Immunol 2020; 21:1327–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oladunni FS, Park J-G, Tamayo PP, et al. : Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat Commun 2020; 11:6122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rathnasinghe R, Strohmeier S, Amanat F, et al. : Comparison of transgenic and adenovirus hACE2 mouse models for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9:2433–2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golden JW, Cline CR, Zeng X, et al. : Human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop severe and fatal respiratory disease. JCI Insight 2020; 5:e142032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yinda CK, Port JR, Bushmaker T, et al. : K18-hACE2 mice develop respiratory disease resembling severe COVID-19. PLoS Pathog 2021; 17:e1009195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Israelow B, Song E, Mao T, et al. : Mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 reveals inflammatory role of type I interferon signaling. J Exp Med 2020; 217:e20201241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung IF, Lung KC, Tso EY, et al. : Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: An open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2020; 395:1695–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davoudi-Monfared E, Rahmani H, Khalili H, et al. : A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of interferon beta-1a in treatment of severe COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64:e01061-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo AM, et al. ; WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium: Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO Solidarity Trial results. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:497–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalil AC, Mehta AK, Patterson TF, et al. ; ACTT-3 study group members: Efficacy of interferon beta-1a plus remdesivir compared with remdesivir alone in hospitalised adults with COVID-19: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9:1365–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.