Abstract

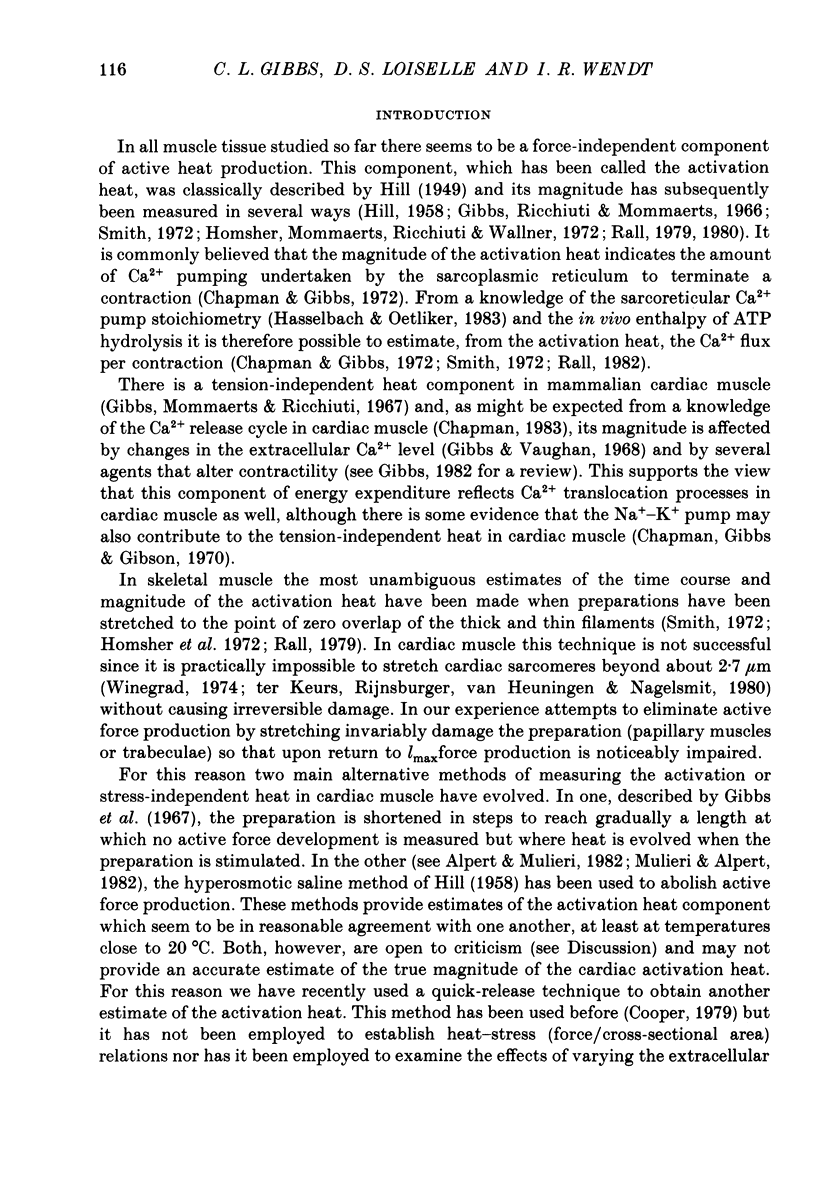

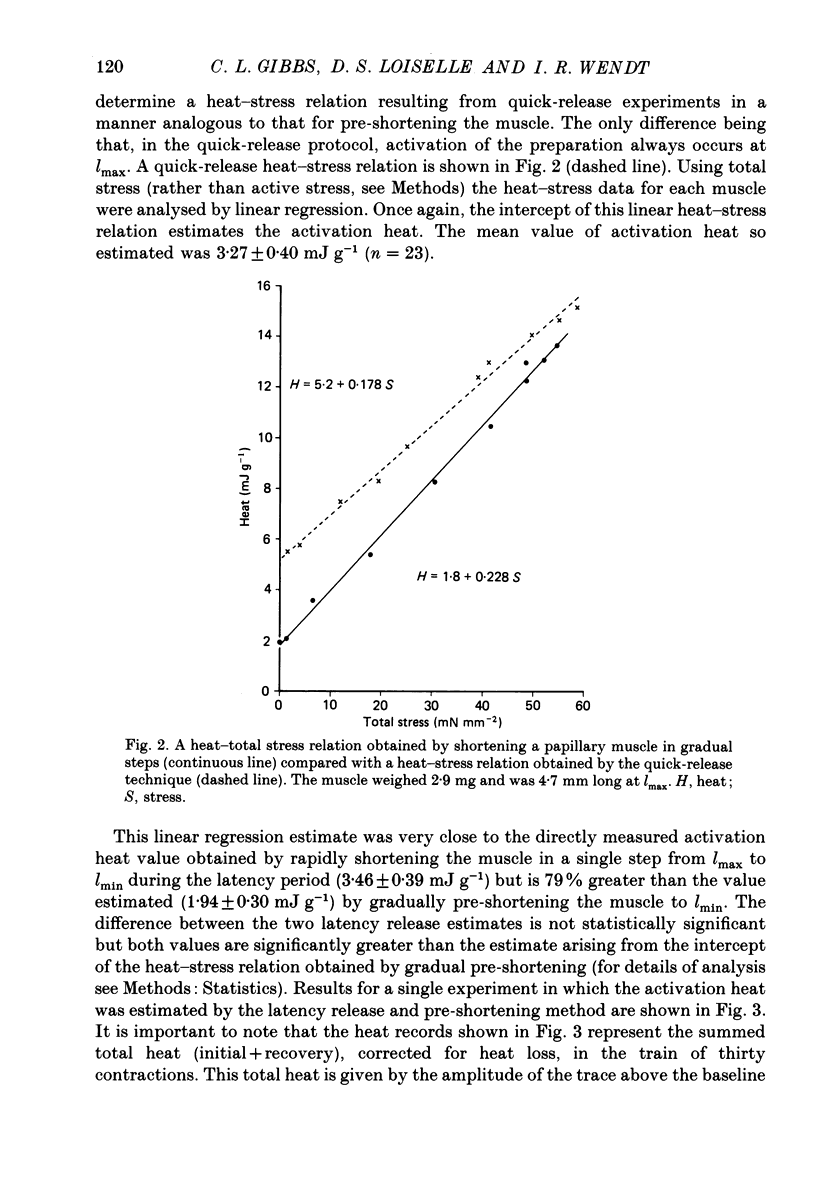

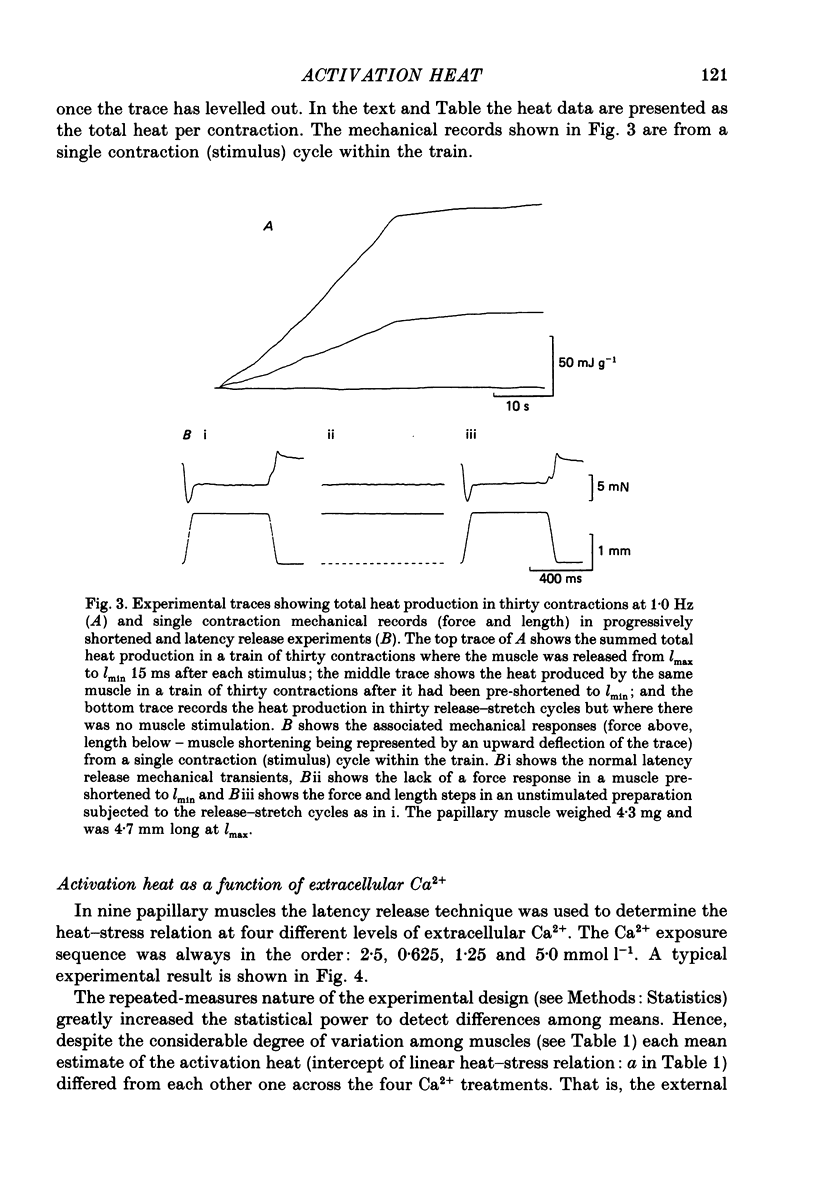

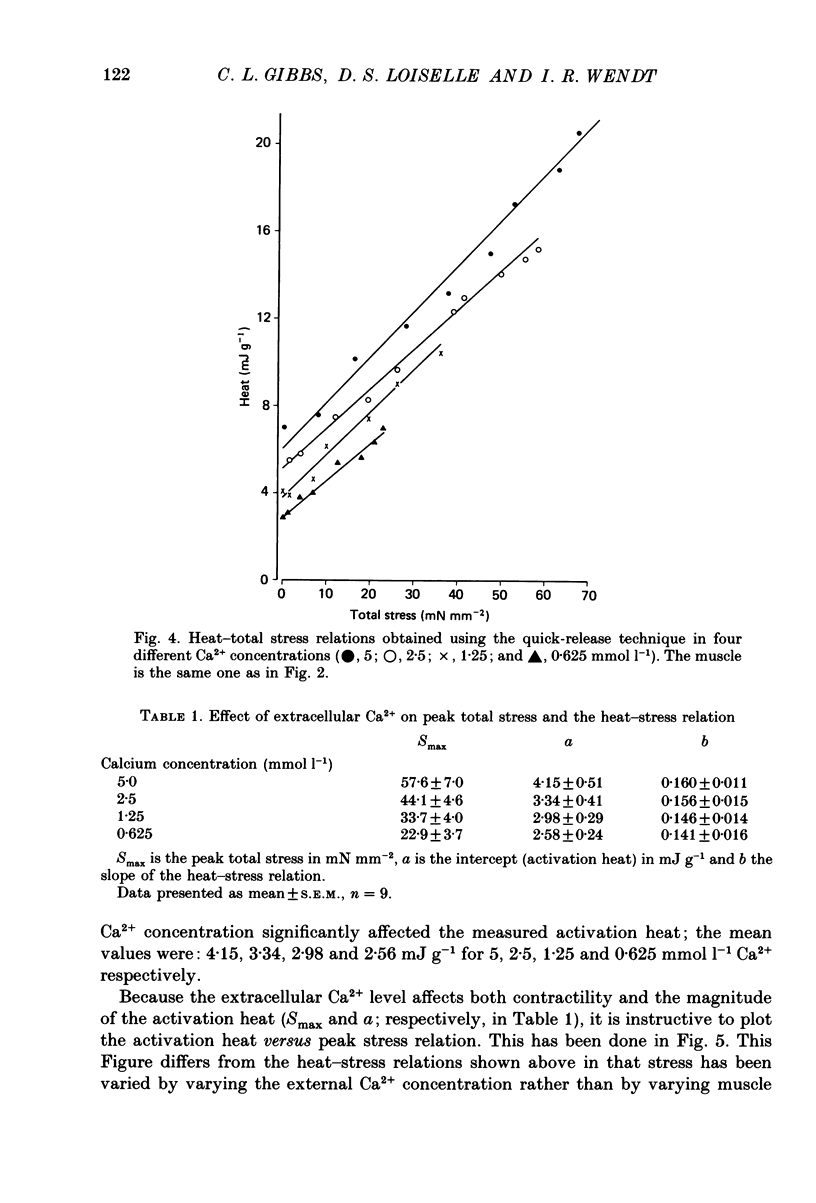

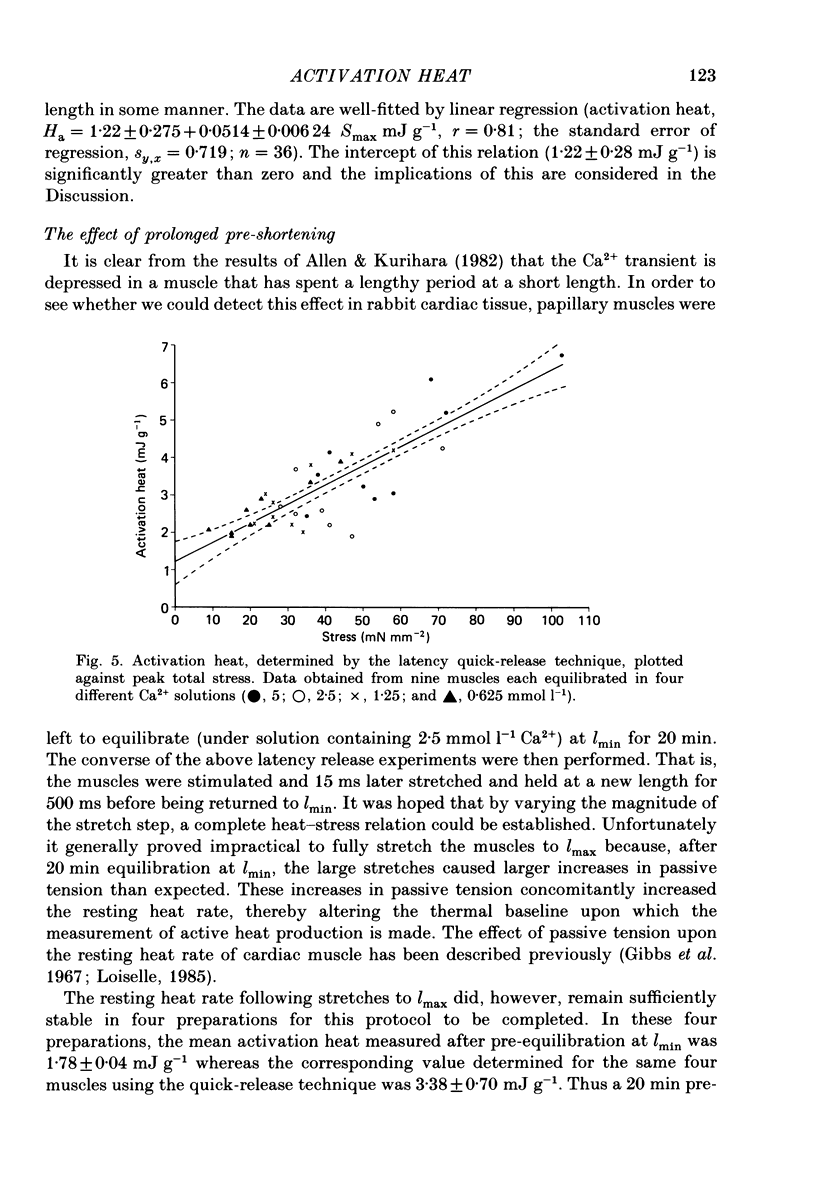

1. Activation heat was estimated myothermically in right ventricular papillary muscles of rabbits using several different methods. 2. Gradual pre-shortening of muscles to a length (lmin) where no active force development took place upon stimulation led to relatively low estimates of activation heat (1.59 +/- 0.26-2.06 +/- 0.57 mJ g-1 blotted wet weight, mean +/- S.E.M., n = 10). 3. Quick releases applied during the latency period, before force development, from lmax to various muscle lengths allowed a heat-stress relation to be established. The zero-stress intercept of this relation estimated the activation heat to be 3.27 +/- 0.40 mJ g-1; this was close to the experimentally measured value of 3.46 +/- 0.39 mJ g-1 (mean +/- S.E.M., n = 23) found by quick release from lmax to lmin. 4. The magnitude of the activation heat measured by the quick-release technique is dependent upon the extracellular Ca2+ concentration and there is good correlation between activation heat magnitude and peak developed stress. 5. In agreement with expectations based on the aequorin data of Allen & Kurihara (1982) a prolonged period of time spent at a short length is shown to depress the subsequently determined activation heat. 6. Hyperosmotic solutions (2.5 x normal) only abolished active stress development at low stimulus rates (0.2 Hz) and the activation heat measured at lmax under these conditions was 2.03 +/- 0.12 mJ g-1 (mean +/- S.E.M., n = 6). This value was significantly lower than the latency release estimate of activation heat in the same preparations (2.93 +/- 0.39 mJ g-1). 7. The latency release method of estimating activation heat results in activation heat values that account for approximately 30% of total active energy flux per contraction; a fraction comparable to that found in skeletal muscle. Calculations based on the data suggest that, under our experimental conditions, total Ca2+ release per beat lies between 50 and 100 nmol g-1 wet weight which would produce less than half-maximal myofibrillar ATPase activity when allowance is made for the passive Ca2+-buffering capacity of the myocardial cell.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Jewell B. R., Murray J. W. The contribution of activation processes to the length-tension relation of cardiac muscle. Nature. 1974 Apr 12;248(449):606–607. doi: 10.1038/248606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. G., Kurihara S. The effects of muscle length on intracellular calcium transients in mammalian cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1982 Jun;327:79–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert N. R., Mulieri L. A. Increased myothermal economy of isometric force generation in compensated cardiac hypertrophy induced by pulmonary artery constriction in the rabbit. A characterization of heat liberation in normal and hypertrophied right ventricular papillary muscles. Circ Res. 1982 Apr;50(4):491–500. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremel R. D., Weber A. Cooperation within actin filament in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Nat New Biol. 1972 Jul 26;238(82):97–101. doi: 10.1038/newbio238097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J. B., Gibbs C. L. An energetic model of muscle contraction. Biophys J. 1972 Mar;12(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(72)86082-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J. B., Gibbs C. L., Gibson W. R. Effects of calcium and sodium on cardiac contractility and heat production in rabbit papillary muscle. Circ Res. 1970 Oct;27(4):601–610. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R. A. Control of cardiac contractility at the cellular level. Am J Physiol. 1983 Oct;245(4):H535–H552. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.4.H535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th Myocardial energetics during isometric twitch contractions of cat papillary muscle. Am J Physiol. 1979 Feb;236(2):H244–H253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.2.H244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jul;245(1):C1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Dependence of the contractile activation of skinned cardiac cells on the sarcomere length. Nature. 1975 Jul 3;256(5512):54–56. doi: 10.1038/256054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Myoplasmic free calcium concentration reached during the twitch of an intact isolated cardiac cell and during calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned cardiac cell from the adult rat or rabbit ventricle. J Gen Physiol. 1981 Nov;78(5):457–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L. Cardiac energetics. Physiol Rev. 1978 Jan;58(1):174–254. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Gibson W. R. Effect of ouabain on the energy output of rabbit cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1969 Jun;24(6):951–967. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Gibson W. R. Energy production in cardiac isotonic contractions. J Gen Physiol. 1970 Dec;56(6):732–750. doi: 10.1085/jgp.56.6.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L. Modification of the physiological determinants of cardiac energy expenditure by pharmacological agents. Pharmacol Ther. 1982;18(2):133–157. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(82)90065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Mommaerts W. F., Ricchiuti N. V. Energetics of cardiac contractions. J Physiol. 1967 Jul;191(1):25–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Ricchiuti N. V., Mommaerts W. F. Activation heat in frog sartorius muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1966 Jan;49(3):517–535. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Vaughan P. The effect of calcium depletion upon the tension-independent component of cardiac heat production. J Gen Physiol. 1968 Sep;52(3):532–549. doi: 10.1085/jgp.52.3.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Huxley A. F., Julian F. J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1966 May;184(1):170–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL A. V. The heat of activation and the heat of shortening in a muscle twitch. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1949 Jun 23;136(883):195–211. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1949.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL A. V. The priority of the heat production in a muscle twitch. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1958 Mar 18;148(932):397–402. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1958.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWARTH J. V. The behaviour of frog muscle in hypertonic solutions. J Physiol. 1958 Nov 10;144(1):167–175. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach W., Oetliker H. Energetics and electrogenicity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump. Annu Rev Physiol. 1983;45:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.45.030183.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsher E., Mommaerts W. F., Ricchiuti N. V., Wallner A. Activation heat, activation metabolism and tension-related heat in frog semitendinosus muscles. J Physiol. 1972 Feb;220(3):601–625. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell B. R. A reexamination of the influence of muscle length on myocardial performance. Circ Res. 1977 Mar;40(3):221–230. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle D. S., Gibbs C. L. Species differences in cardiac energetics. Am J Physiol. 1979 Jul;237(1):H90–H98. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.237.1.H90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle D. S. The rate of resting heat production of rat papillary muscle. Pflugers Arch. 1985 Sep;405(2):155–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00584537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Alpert N. R. Activation heat and latency relaxation in relation to calcium movement in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1982 Apr;60(4):529–541. doi: 10.1139/y82-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Luhr G., Trefry J., Alpert N. R. Metal-film thermopiles for use with rabbit right ventricular papillary muscles. Am J Physiol. 1977 Nov;233(5):C146–C156. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.233.5.C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce G. N., Philipson K. D., Langer G. A. Passive calcium-buffering capacity of a rabbit ventricular homogenate preparation. Am J Physiol. 1985 Sep;249(3 Pt 1):C248–C255. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.249.3.C248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall J. A. Dependence of energy output on force generation during muscle contraction. Am J Physiol. 1978 Jul;235(1):C20–C24. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1978.235.1.C20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall J. A. Effects of previous activity on the energetics of activation in frog skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1980 Jun;75(6):617–631. doi: 10.1085/jgp.75.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall J. A. Effects of temperature on tension, tension-dependent heat, and activation heat in twitches of frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1979 Jun;291:265–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall J. A. Energetics of Ca2+ cycling during skeletal muscle contraction. Fed Proc. 1982 Feb;41(2):155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith I. C. Energetics of activation in frog and toad muscle. J Physiol. 1972 Feb;220(3):583–599. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Wise R. M., Shiner J. S., Briggs F. N. Calcium requirements for cardiac myofibrillar activation. Circ Res. 1974 Apr;34(4):525–530. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H., Hayashi T., Shirahata M. Ventricular systolic pressure-volume area as predictor of cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1981 Jan;240(1):H39–H44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.1.H39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K. T., Janicki J. S. Myocardial oxygen consumption: the role of wall force and shortening. Am J Physiol. 1977 Oct;233(4):H421–H430. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1977.233.4.H421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie D. R. Heat work and phosphorylcreatine break-down in muscle. J Physiol. 1968 Mar;195(1):157–183. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Keurs H. E., Rijnsburger W. H., van Heuningen R., Nagelsmit M. J. Tension development and sarcomere length in rat cardiac trabeculae. Evidence of length-dependent activation. Circ Res. 1980 May;46(5):703–714. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]