ABSTRACT

Background:

Pregnant women need special attention during emergencies and infectious disease outbreaks. Pregnancy is a standalone risk factor for the severity of COVID-19, heightening the vulnerability of both the mother and foetus. Neonatal admission, foetal distress, and low birth weight were correlated to the severity of COVID-19. The aim of this study was to provide a clinical overview and characteristics of neonates from mothers who were confirmed with COVID-19.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Sulianti Saroso Infectious Disease Hospital (SSIDH) from March 2020 to December 2022. Inclusion criteria included pregnant women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who either gave birth in a hospital according to the regulations of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. All newborns were tested using RT-PCR SARS-COV-2 swab tests within 24 hours after birth. We used electronic medical records as a secondary source.

Result:

A total of 181 pregnant women with positive SARS-CoV-2, 103 (56.9%) gave birth, with 101 (98.1%) undergoing caesarean section. Of the 103 who gave birth, a small proportion of mothers with COVID-19 were aged <20 years or >35 years (29.13%) and had preterm deliveries (15.53%). All newborns born to SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers were alive. The severity of illness was associated with the first-minute and fifth-minute APGAR scores of newborns (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The severity of maternal COVID-19 impacts newborns’ 1-minute and 5-minute APGAR scores. Implementing a strict COVID-19 protocol effectively prevents neonatal infections.

Keywords: APGAR score, COVID-19, gestation, newborn, pregnancy

Background

Since the beginning of 2020, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has produced an unprecedented disaster worldwide.[1,2] One group of people who need special care during emergencies and infectious diseases is pregnant women. Many studies showed that pregnant women with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) infection get a more severe form of the virus, which increases their risk of mortality to 35.0% and causes pneumonia in over 25% of cases.[3,4] Also, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), hospitalisation rates for pregnant women with SARS CoV-2 infection disease-19 (COVID-19) were higher than non-pregnant individuals at the same age (31.5% versus 5.8%).[5] The UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) study showed that severe COVID-19 occurred more often in the later trimester.[6]

Most findings report the mortality risk in COVID-19-infected pregnant women as low, as there are only a few cases of patients developing respiratory distress.[7] Pneumonia during pregnancy has also been linked to a greater risk of preterm birth in neonates as compared to the general population.[8] According to other studies, COVID-19 does not pose additional risks for pregnant women, newborns, or pregnancy outcomes. Pregnant women diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 generally have a positive prognosis, and their clinical progression is similar to that of non-pregnant women.[9] Infection with COVID-19 in pregnant individuals can result in premature births, caesarean deliveries, and maternal fatalities. At the same time, newborns may face complications such as low birth weight, respiratory distress syndrome, prematurity, being born positive for SARS-CoV-2, requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and neonatal mortality.[9] A recent study found that neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 had a 25.4 times higher likelihood of having an Apgar score below seven than those born to mothers without COVID-19, indicating that maternal COVID-19 infection affects neonatal Apgar scores.[10]

Pregnant women infected with COVID-19 exhibit similar clinical presentations to non-pregnant women in laboratory and radiographic examinations.[5,11] The most frequently observed issues in pregnant women include reduced lymphocyte counts, increased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and pregnancy-related complications such as preterm birth and caesarean delivery. These findings were derived from a compilation of various studies on the subject.[12,13,14]

According to the Indonesian Ministry of Health (2020), cases of COVID-19 in children show a relatively high mortality rate among those aged 0-4 years, with a recovery rate of 22%. Cases of COVID-19 in children require special attention; according to the Indonesian Ministry of Health (2020), the number of COVID-19 infections in children reached 8.1% or approximately 6,700 children out of the total cases. According to a study carried out in Indonesia that assessed the outcomes for mothers and infants during the pandemic, 60% of the 427 women hospitalised due to COVID-19 gave birth in the hospital, and six newborns tested positive for COVID-19 within the first 12 hours after their birth.[15]

The study of SARS-CoV-2 infection among pregnant women is essential. The association between the maternal COVID-19 severity and the birth outcomes (premature birth, birth weight, neonatal infections, Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration (APGAR) Score has never been studied in national infectious disease facilities in Indonesia. As a result, it is crucial to gather and document data regarding COVID-19 disease among pregnant women and its impact on maternal and newborn health outcomes. This study investigates the association between maternal COVID-19 severity and birth outcomes, such as APGAR scores, neonatal infections, premature birth, and neonatal birth weight at Sulianti Saroso Infectious Disease Hospital (SSIDH).

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using electronic medical records. We studied all pregnant women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection tested using RT-PCR and followed them up until giving birth in our hospital from March 2020 until December 2022 at SSIDH. We conducted COVID-19 screenings for all pregnant women according to the regulations of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. Management of pregnant patients includes supportive treatment that is appropriate for their pregnancy condition. Services for labour and pregnancy termination must take into account various factors, such as the gestational age and the health status of both the mother and foetus. It is important to consult with an obstetrician, paediatrician, and other relevant specialists based on the pregnancy condition and an intensive care consultant.[16] Regardless of their severity level, all newborns of the mother with confirmed SARS-COV-2 were tested using RT-PCR swab tests within the first 24 hours after birth. The sample size of the total population includes 103 mothers who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during childbirth, along with their infants.

Variables

The levels of illness are categorised as mild pain with mild clinical symptoms, moderate pain accompanied by mild pneumonia symptoms, severe pain with severe pneumonia or acute respiratory infection symptoms, and critical illness characterised by Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) manifestations.[16] The maternal COVID-19 severity was divided into the mild/moderate and severe/critical groups. The characteristics of the mother respondents assessed in this study included maternal age, gestational age, gravida, mode of delivery, COVID-19 severity, laboratory parameters (vitamin D, haemoglobin, NLR, D-dimer), chest X-ray, length of stay (LOS), and the mother’s outcome. The newborn variables included APGAR scores, neonatal infections, premature birth, and neonatal birth weight. The Apgar score is a standardised evaluation of an infant’s colour, respiratory effort after birth, muscle tone, heart rate, and reflexes.[17,18] The range of APGAR scores is 0 to 10, while a score between 7 and 10 is average; a score between 4 and 6 (moderate) and 0 to 3 (low) needs evaluation and requires monitoring for 5 minutes.[18,19] Meanwhile, the 1-minute and 5-minute APGAR scores predict neonatal morbidity; the 5-minute score is accepted as a more useful predictor of outcome, irrespective of birth weight.

Various researchers have discovered that the combined ratios of specific haematological parameters, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (d-NLR), are important. Elevated D-dimer levels in COVID-19 can be quickly identified as indicators of disease severity, pulmonary complications, and the risk of venous thromboembolism in pro-thrombotic conditions. A D-dimer level of ≥0.5 mg/L is classified as hypercoagulable.[20,21] 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D is classified as deficient when levels are below 20 ng/mL and insufficient when levels range from 20 to just under 30 ng/mL.[22]

Preterm is defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed.[23]

Anaemia occurs when red blood cells’ haemoglobin (Hb) level falls below the usual standard. A pregnant woman is diagnosed with anaemia if her Hb level is below 11 g/dl.[24] Multigravidas are patients who have had more than one pregnancy.[25]

The data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solution Inc, Chicago, IL, USA (SPSS) for Windows 24.0. Descriptive analysis for categorical data, including maternal age, gestational age, gravida, Length of Stay (LOS), maternal outcomes, COVID-19 vaccination, severity, vitamin D deficiency, haemoglobin levels, hypercoagulability, and Chest X-ray results, was conducted using frequency (n) and proportion (%). For the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), median and Inter Quartile Range (IQR) were used for descriptive analysis. The Chi-squared test was employed to examine the relationship between two categorical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality revealed that the NLR data distribution was not normal (P value < 0.05), so the median and IQR were applied. The Research Ethics Committee of SSIDH has approved this study under Protocol Number 28/XXXVIII.10/V/2023.

Results

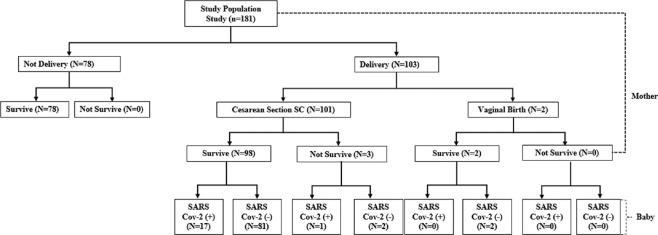

During the study period, 181 pregnant women with positive SARS-CoV-2 were admitted to SSIDH, 103 (56.9%) of whom gave birth, while 101 (98.1%) of them underwent caesarean section, and all newborns born to SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers within the first 24 hours were alive. About 3 (2.97%) mothers died post-delivery [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow population study

A small proportion of mothers with COVID-19 were aged <20 years or >35 years, had preterm deliveries, hospital stays longer than 10 days, anaemia (11 g/dL), but the majority were multigravida and most delivered via caesarean section. A small portion of mothers received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine or none [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women on the birth outcomes with confirmed SARS-CoV-2

| Characteristics | Newborns with SARS CoV-2 Positive (n=18) | Newborns SARS CoV-2 Negative (n=85) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Mother, berisiko (<20 atau >35 tahun) (n, %) | 6 (33.3) | 24 (28.2) | 0.883 |

| Gestational age at delivery, preterm birth (n, %) | 3 (16.7) | 13 (15.3) | 1.000* |

| Gravid, multigravida (n, %) | 13 (72.2) | 68 (80.0) | 0.529* |

| Length of Stay, days (n, %) | 3 (20.0) | 16 (18.2) | 1.000* |

| Haemoglobin, anaemia (n, %) | 0.153 | ||

| NLR (median, IQR) | 5.6 (3.1-7.6) | 4.7 (3.5-6.6) | 0.385* |

| Mode of delivery, vaginal delivery (n, %) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | 1.000** |

| Vitamin D deficiency (n, %) | 17 (94.4) | 82 (96.5) | 0.542** |

| D-dimer, hypercoagulable (n, %) | 9 (50) | 51 (60) | 0.604 |

| Chest X-ray, pneumonia (n, %) | 14 (77.8) | 69 (81.2) | 0.747** |

| Mothers who received at least one dose of COVID-19 Vaccine and no dose (n, %) | 1 (5.6) | 15 (17.6) | 0.293** |

| Severe/Critical (n, %) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1.000** |

*Mann Whitney U. **Fisher Exact. P (α=5%)

Characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 on the birth outcomes

There were no differences between the characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 on the birth outcomes. The birth outcomes divided into the newborns with positive group and negative SARS-CoV-2 group [Table 1].

The association between the maternal COVID-19 severity and the birth outcomes

Table 2 shows the association between maternal COVID-19 severity and birth outcomes. The majority of mothers with mild to moderate COVID-19 had newborns with Apgar scores of 7 or higher, both in 1-minute and 5-minute terms of gestational age at delivery and normal birth weight. A significant relationship was found between disease severity and the 1-minute APGAR score (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

The maternal COVID-19 severity and the birth outcomes (n=103)

| Severity | AS 1-Minute | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| AS <7 | AS ≥7 | ||

| Severe/Critical | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.000 |

| Mild/moderate | 6 (5.9) | 95 (94.1) | |

|

| |||

| Severity | AS 5- Minutes | P | |

|

| |||

| AS <7 | AS ≥7 | ||

|

| |||

| Severe/Critical | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0.058 |

| Mild/moderate | 2 (2) | 99 (98) | |

|

| |||

| Severity | Gestational Age at delivery | P* | |

|

| |||

| Pre | Aterm | ||

|

| |||

| Severe/Critical | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0.288 |

| Mild/moderate | 15 (14.9) | 86 (85.1) | |

|

| |||

| Severity | Birth weight | P* | |

|

| |||

| Low (<2500 g) | Normal (≥2500 g) | ||

|

| |||

| Severe/Critical | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1.000 |

| Mild/moderate | 15 (14.9) | 86 (85.1) | |

*Fisher Exact Test (α < 5%)

Discussion

In this study, we followed 103 pregnant women followed up until delivery; 101 (98%) pregnant women experienced mild/moderate COVID-19 symptoms. This figure is not very different from previous studies; a prior study consistently found 86.0% mild cases and 14.0% severe and critical cases.[26] According to another study, of pregnant women infected with COVID-19, 73.5% were asymptomatic/mild cases, and roughly 26.5% were between moderate and severe cases.[27]

Earlier studies have shown a heightened risk of negative obstetric and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with severe cases of COVID-19.[27,28,29] Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that pregnant women with moderate to severe COVID-19 faced a significantly increased risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, neonatal infection, and admission to the neonatal ICU (P < 0.001).[27] A cohort study conducted in Wuhan showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy results in preterm births and caesarean deliveries.[28] We found that the two severe/critical pregnant women were associated with the birth outcomes, such as lower APGAR scores <7 at the 1-minute (P < 0,05), and one baby continued AS <7 at the 5-minute. Unlike a retrospective study involving seven newborns from mothers with SARS-CoV-2, it was found that all infants had a first-minute APGAR score of (8-9) and a five-minute APGAR score of (9-10).[30] In this study, however, the proportion of first-minute APGAR scores <7 was lower than that of scores ≥7, and the same was true for the five-minute APGAR scores. The significance may be attributed to chance. Additionally, the researchers did not examine the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the APGAR scores of the newborns.

Dr. Virginia Apgar created a score in the early 1950s to evaluate a newborn’s physical state and whether resuscitation is necessary.[18,31,32] The 5-minute APGAR score was a more accurate indicator of newborn survival than the original one-minute.[18] Heart rate, respiratory effort, muscular tone, grimace/reflex irritability, and appearance/skin colour comprise the APGAR score. Each element is assigned a number between 0 and 2, meaning the overall score varies from 0 to 10, where higher numbers denote more excellent physical health. Term infants (≥37 weeks) that have a low APGAR score—generally considered to be <5 or <7 are more likely to experience neonatal mortality. It was recently found that among term newborns with 5-minute APGAR scores in the normal range (7 to 10), newborn scores 7-8 had a greater risk of neonatal death than 9 or 10.[33,34,35]

Interventions that may have affected APGAR score values, changes in APGAR scores, and newborn survival were not disclosed to us during the first stabilisation.[27] Though this may not be helpful prognostic information, the observation that an APGAR score improvement from 5 to 10 minutes is linked to reduced neonatal mortality suggests that infants whose scores improved likely had better health at 5 minutes compared to those whose scores remained unchanged.

This study found that all infants with low birth weight were delivered by mothers experiencing severe or critical illness. However, no relationship was identified between SARS-CoV-2 infection in mothers and the birth weight of the newborns. These findings align with those from a referral hospital in Turkey.[36] A study conducted in Indonesia showed that the average birth weight of newborns is normal for both those infected with SARS-CoV-2 and those who are not.[37] In contrast to previous studies, a multicentre study in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and a systematic study showed a higher incidence of lower birth weight (30.5-42.8%).[27,38,39,40]

Our study shows that eighteen newborns (17.5%) presented with RT-PCR positive. Similar findings were consistently demonstrated by Zamaniyan et al.[41] and Alzamora et al.,[42] suggesting the possibility of vertical maternal-foetal transmission. It hypothesises the potential for intrauterine vertical transmission via the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) putative surface receptor of SARS-CoV-2-sensitive cells.[36] Damage to the placental barrier due to extreme maternal hypoxia may also be a route of transmission for SARS-CoV-2.[43,44,45] Numerous studies have also noted this observation. However, most newborns with infections were only mildly affected during the prenatal phase.[46,47]

This study’s findings suggest that there is no association between the severity of COVID-19 in mothers giving birth and SARS-CoV-2 infection in newborns. These results align with those from a study at a referral hospital in Turkey.[36] Different from a case report describing a pregnant woman who had no COVID-19 symptoms and gave birth to a newborn with typical COVID-19 symptoms and confirmed a positive SARS-COV-2 RT-PCR. This shows that vertical transmission can very likely happen in the third trimester of pregnancy or at delivery, even when the mother has nonspecific COVID-19 symptoms.[48] In order to take precautions and guarantee the safety of mothers, newborns, and medical staff, it is important to do a routine COVID-19 screening of pregnant women, either having specific or nonspecific symptoms or signs, before delivery. Some case reports addressed the likelihood of vertical transmission in several cases whose RT-PCR was negative but had higher concentrations of SARS-COV-2 specific antibodies (IgG or IgM) in the newborn blood serum that were identical to maternal blood.[49,50] This is justified by the inactively generated transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies from mother to foetus.[46,49]

It’s important to recognise that viral infections can be transmitted not only through intrauterine vertical transmission but also during the foetus’s passage through the birth canal, after birth, through breastfeeding, skin contact, or exposure to droplets from the mother or others when they cough or sneeze.[48] On the contrary, a study used the viral nucleic acid test to examine the placenta of one infected newborn within the first 12 hours. The result was negative for SARS-CoV-2, indicating that intrauterine vertical transmission of the infection might not occur, though there is little evidence to support this theory.[30] The research by Dong et al.[49] found that although a neonate’s serological test for COVID-19 may occasionally come out negative, signs of SARS-COV-2 infection may not show up for up to three to seven days after infection. It emphasises the need for more studies to investigate immunological and serological traits of newborns born from women with SARS-COV-2 infections and vertical transmission.

Study limitations

We found that the retrospective design, small sample size, and homogeneity of the ethnicity of the study populations may affect the generalisability of the results and uncertainty surrounding the purpose of the newborns’ admission to the perinatology room—whether the PCR test was positive or just for isolation—are just a few of the study’s limitations. In this study, all newborns were admitted to the perinatology room prior to SARS-CoV-2 testing. Newborns testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 were cared for in conjunction with their mothers.

Conclusion

Median age and gestational age at delivery were within normal limits. The mean haemoglobin level of delivery women was normal, and a small percentage of delivery women were hypercoagulable. The current investigation found a significant association between the severity of COVID-19 and The first-minute APGAR score; however, it is not significant in relation to other outcomes. It is essential to consider the risk of poor neonatal outcomes in infants born to pregnant women with COVID-19. The availability of facilities and the involvement of paediatric specialists are crucial in providing care for newborns from mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Sulianti Saroso Hospital, Number. 28/XXXVIII.10/V/2023.

Consent to participate

Not applicable, but all patients admitted to Sulianti Saroso Hospital must agree to the general consent in the medical record document, including for research.

Authors contributions

A.N.T. and S.M. were responsible for data collection, data analysis and research conceptualisation. R.M. and K.W. were responsible for data collection. A.D.W. and N.M. were responsible for overseeing the write-up. S.M. and N.M. were refining the methodology.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director of Sulianti Saroso Infectious Disease Hospital and Research Unit.

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Al-Qahtani AA. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Emergence, history, basic and clinical aspects. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27:2531–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai C-C, Shih T-P, Ko W-C, Tang H-J, Hsueh P-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vouga M, Favre G, Martinez-Perez O, Pomar L, Acebal LF, Abascal-Saiz A, et al. Maternal outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 severity among pregnant women. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13898. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92357-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfaraj SH, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:501–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT, Woodworth K, Galang RR, Zambrano LD, et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status-United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:769–75. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vousden N, Bunch K, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, O'Brien P, et al. The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: A national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gidlöf S, Savchenko J, Brune T, Josefsson H. COVID-19 in pregnancy with comorbidities: More liberal testing strategy is needed. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:948–9. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maleki Dana P, Kolahdooz F, Sadoughi F, Moazzami B, Chaichian S, Asemi Z. COVID-19 and pregnancy: A review of current knowledge. Le Infez Med. 2020;28:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel BM, Khanna D, Khanna S, Hapshy V, Khanna P, Kahar P, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on pregnant women and newborns: A review. Cureus. 2022;14:e30555. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Sehat M, Vahedpour Z, Talebian P. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19: A prospective cohort study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:449–56. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu X, Sun R, Chen J, Xie Y, Zhang S, Wang X. Radiological findings and clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150:58–63. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, Guo Y. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.028. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Della Gatta AN, Rizzo R, Pilu G, Simonazzi G. Coronavirus disease 2019 during pregnancy: A systematic review of reported cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, Cheng BH, Zhou XC, Li J, et al. [Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55:166–71. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20200218-00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulaiman MR, Varwati L. Ministry of Health: More than Half of COVID-19 Child Patient Deaths Occur in Toddlers. Suara.com. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ditjen PP. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Vol. 5. Indonesia: 2020. PL. Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia. Available from: https://doi.org/10.33654/math.v4i0.299. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong J, Crawford K, Jarrett K, Triggs T, Kumar S. Five-minute Apgar score and risk of neonatal mortality, severe neurological morbidity and severe non-neurological morbidity in term infants – an Australian population-based cohort study. Lancet Reg Heal-West Pacific. 2024;44:101011. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101011. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon LV, Shah M, Bragg BN. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Apgar Score. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong J, Crawford K, Jarrett K, Triggs T, Kumar S. Five-minute Apgar score and risk of neonatal mortality, severe neurological morbidity and severe non-neurological morbidity in term infants – an Australian population-based cohort study. Lancet Reg Heal-West Pacific. 2024;44:101011. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101011. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poudel A, Poudel Y, Adhikari A, Aryal BB, Dangol D, Bajracharya T, et al. D-dimer as a biomarker for assessment of COVID-19 prognosis: D-dimer levels on admission and its role in predicting disease outcome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0256744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pertiwi IA, Sudarsono TA, Kusuma Wardani DP, Rahaju M. Literature review: Hubungan Kadar D-Dimer dengan Tingkat Keparahan Pasien Covid-19. J Surya Med. 2023;9:273–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sowah D, Fan X, Dennett L, Hagtvedt R, Straube S. Vitamin D levels and deficiency with different occupations: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:519. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4436-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO. Preterm birth 2023. [[Last accessed 2024 Sep 09]]. Avaialble from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth .

- 24.Kemenkes. Pedoman Pemberian Tablet Tambah Darah (TTD) bagi Ibu Hamil pada Masa Pandemi COVID-19. Jakarta, Indonesia: Jakarta Kementrian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parveen K, Baloch H, Khurshid F, Ayman, Bashir B, Mahboob S, et al. Comparative analysis of pregnancy complications in primigravida versus multigravida. J Heal Rehabil Res. 2024;4:1581–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghaamoo S, Ghods K, Rahmanian M. Pregnant women with COVID-19: The placental involvement and consequences. J Mol Histol. 2021;52:427–35. doi: 10.1007/s10735-021-09970-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dileep A, ZainAlAbdin S, AbuRuz S. Investigating the association between severity of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Sci Rep. 2022;12:3024. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07093-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang R, Mei H, Zheng T, Fu Q, Zhang Y, Buka S, et al. Pregnant women with COVID-19 and risk of adverse birth outcomes and maternal-fetal vertical transmission: A population-based cohort study in Wuhan, China. BMC Med. 2020;18:330. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01798-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samadi P, Alipour Z, Ghaedrahmati M, Ahangari R. The severity of COVID-19 among pregnant women and the risk of adverse maternal outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;154:92–9. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, Xiong Z, Wang S, Lin X, et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:559–64. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeagle KP, O’Brien JM, Curtin WM, Ural SH. Are gestational and type II diabetes mellitus associated with the Apgar scores of full-term neonates? Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:603–7. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S170090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medeiros TK de S, Dobre M, da Silva DMB, Brateanu A, Baltatu OC, Campos LA. Intrapartum fetal heart rate: A possible predictor of neonatal acidemia and APGAR score. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1489. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Razaz N, Cnattingius S, Joseph KS. Association between Apgar scores of 7 to 9 and neonatal mortality and morbidity: Population based cohort study of term infants in Sweden. BMJ. 2019;365:l1656. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1656. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sven C, Stefan J, Neda R. Apgar score and risk of neonatal death among preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:49–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watterberg KL, Aucott S, Benitz WE, Cummings JJ, Eichenwald EC, Goldsmith J, et al. The Apgar Score. Pediatrics. 2015;136:819–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2651. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arinkan SA, DallıAlper EC, Topcu G, Muhcu M. Perinatal outcomes of pregnant women having SARS-CoV-2 infection. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60:1043–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacob A, MTP M, Gopinath R, Divakaran B, Harris T. Clinical profiles of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19. Paediatr Indones. 2021;61 doi: 10.14238/pi61.5.2021.277-82. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubey P, Thakur B, Reddy S, Martinez CA, Nurunnabi M, Manuel SL, et al. Current trends and geographical differences in therapeutic profile and outcomes of COVID-19 among pregnant women-A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:247. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03685-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahin D, Tanacan A, Erol SA, Anuk AT, Eyi EGY, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, et al. A pandemic center's experience of managing pregnant women with COVID-19 infection in Turkey: A prospective cohort study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151:74–82. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith V, Seo D, Warty R, Payne O, Salih M, Chin KL, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with COVID-19 infection: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamaniyan M, Ebadi A, Aghajanpoor S, Rahmani Z, Haghshenas M, Azizi S. Preterm delivery, maternal death, and vertical transmission in a pregnant woman with COVID-19 infection. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40:1759–61. doi: 10.1002/pd.5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alzamora MC, Paredes T, Caceres D, Webb CM, Webb CM, Valdez LM, et al. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:861–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: Systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:15–27. doi: 10.1002/uog.22088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valdés G, Neves LAA, Anton L, Corthorn J, Chacón C, Germain AM, et al. Distribution of angiotensin-(1-7) and ACE2 in human placentas of normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta. 2006;27:200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C, Zhou Y-H, Yang H-X, Poon LC. Intrauterine vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2: what we know so far. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55:724–5. doi: 10.1002/uog.22045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, Tang Y, Deng Q, Zhang W, et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323:1848–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeng L, Xia S, Yuan W, Yan K, Xiao F, Shao J, et al. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:722–5. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/v12020194. doi: 10.3390/v12020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829–38. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vendola N, Stampini V, Amadori R, Gerbino M, Curatolo A, Surico D. Vertical transmission of antibodies in infants born from mothers with positive serology to COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:331–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]