Abstract

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a common complication in patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD). However, the early diagnosis and understanding of the pathogenesis of CAC in SIHD patients remain underdeveloped. This study aimed to analyze aberrant alterations in the serum proteome of SIHD patients, as well as SIHD patients with severe CAC (CAC_SIHD), and to explore the potential risk factors of CAC in SIHD patients. Serum proteomic profiles were obtained from individuals with SIHD (n = 6), CAC_SIHD (n = 6), and healthy controls (n = 9), and were analyzed using nano liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). The aberrant alterations in proteins and immune cells in the serum of SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients were characterized through differential protein expression analysis and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis analysis, respectively. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were further subjected to gene ontology functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses. Finally, Receiver Operating Characteristic analysis was performed on the DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD to identify potential predictive factors of CAC. Abnormalities in multiple complement pathways and lipid metabolism were observed in SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients. Moreover, SIHD and CAC_SIHD were characterized by an increased presence of T cells and natural killer cells, along with a reduced presence of B cells. Subsequent analysis of serum proteins revealed that RNASE1 and MSLN may be potential predictive indicators for the early detection and diagnosis of CAC in SIHD patients. In conclusion, our research extensively examined the variations in serum proteins in patients with SIHD and CAC_SIHD, identifying key indicators and metabolic pathways associated with these conditions. These findings not only provide new insights into the pathological mechanisms of SIHD and CAC_SIHD, but also suggest potential factors for the early diagnosis of CAC in SIHD patients, which imply potential clinical applications.

Keywords: Ischemic heart disease (SIHD), Coronary artery calcification (CAC), Proteomic, RNASE1, MSLN

Background

Stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD), primarily caused by atherosclerotic plaque, represents the most common clinical manifestation of ischemic heart disease (Kyavar and Alemzadeh-Ansari 2022). Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease and is one of the leading causes of mortality globally (Williams et al. 2014; Blaha et al. 2009; Yejin et al. 2022). Furthermore, CAC is a common complication observed in patients with SIHD. Research indicates that the incidence of vascular calcification increases with age, with 70.93% of men and 75% of women aged 65 and oldering exhibit varying degrees of vascular calcification (Newman et al. 2001; Panh et al. 2017). CAC is often viewed as a normal progression of atherosclerosis and is considered a frequent clinical symptom associated with this condition (Alexopoulos and Raggi 2009; Otsuka et al. 2014). Additionally, lifestyle choices, genetic factors, and the gut microbiome significantly influence the onset and progression of CAC (Gupta et al. 2017; Bowman and McNally 2012; Liu et al. 2019). In recent years, significant progress has been made in understanding the role of proteins in CAC through the application of proteomics, a powerful tool that allows for large-scale protein analysis in biological systems (Lindsey et al. 2015; Basak et al. 2016). The emergence of mass-spectrometry-based high-throughput proteomic technology has facilitated the identification of novel biomarkers for the disease, enhanced the understanding of molecular pathways involved in coronary artery disease (CAD), and uncovered potential therapeutic targets (Basak et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2024). Moreover, a number of proteome-based investigations on vascular calcification have provided fresh insights into its underlying mechanism (Qianqian et al. 2011; Bu-Chun et al. 2022). The significant enrichment of exosomal proteins by circulating calcium is a primary cause of aortic valve calcification (Zhang et al. 2018; Carracedo et al. 2019). Under conditions of moderate to severe cardiovascular disease and elevated phosphorus levels, the levels of vascular calcification-promoting proteins in matrix vesicles increase, thereby promoting exosome release (Bakhshian et al. 2017). Notch3 protein in human umbilical vein endothelial cells has been shown to increase the calcification and senescence of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and to regulate these processes through the mTOR signaling pathway (Lin et al. 2019; Mahmoud et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2011). However, proteomics studies on clinical samples of SIHD and CAC remain limited. Therefore, further research is needed to improve the early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of CAC in SIHD patients.

Here, we performed proteomic analysis on serum samples collected from patients with SIHD, patients with both SIHD and CAC, and healthy controls. Our aim was to identify candidate proteins involved in the calcification process in blood. Our work provides unique insights into protein expression in vascular calcification process in the bloodstream. These findings offer valuable insights into protein expression in vascular calcification, suggesting potential avenues for developing targeted therapies to prevent or treat CAC and its associated complications.

Materials and methods

Study population

From November 2019 to January 2021, we recruited patients referred to the Cardiovascular Department at the First People's Hospital of Yunnan Province, China. The diagnosis of coronary heart disease and SIHD followed the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) criteria (Members et al. 2023). All participants underwent coronary angiography to assess for single-vessel coronary artery disease with stenosis greater than 50%.

Our study included 21 age- and sex-matched participants, divided into three groups: (i) The SIHD group, which included six SIHD patients without CAC who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting, (ii) the CAC_SIHD group, consisting of six SIHD patients with severe CAC who required rotational atherectomy and PCI with stenting, and (iii) the control group, which comprised nine participants with normal coronary angiography results. Exclusion criteria included malignancy, autoimmune diseases, hematological disorders, and acute myocardial infarction within the past month.

Blood samples were collected in the morning following an overnight fast, one day prior to coronary angiography. The samples were stored in heparinized tubes and kept at 4 °C for 2 h. Serum was then isolated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min and stored at − 80 °C until examination.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (2016LH083) and conformed to relevant ethical guidelines for human and animal research. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample preparation and nano liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis

For each sample, 1 μg of total peptides was separated and analyzed using an EASY-nLC 1200 system coupled with a Q Exactive HFX Orbitrap instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), equipped with a nano-electrospray ion source. Separation was performed on a reversed-phase column (100 μm ID × 15 cm, Reprosil Pur 120 C18 AQ, 1.9 μm, Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch, Germany). Mobile phases consisted of H2O with 0.1% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile (phase A), and 80% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (phase B). A 90-min gradient was applied at a flow rate of 300 nL/min for separation. The gradient for phase B was as follows: 2–5% for 2 min, 5–22% for 68 min, 22–45% for 16 min, 45–95% for 2 min, and 95% for 2 min.

Data-dependent acquisition was performed in profile mode with positive polarity using an Orbitrap analyzer. The resolution was set to 120,000 at 200 m/z. The m/z range for mass spectrometry 1 (MS1) was 350–1600. The resolution for MS2 was set to 45,000, with a fixed first mass of 110 m/z. The automatic gain control (AGC) target for MS1 was set to 3 × 10⁶ with max injection time (IT) of 30 ms, while for MS2, the AGC target was set to 1 × 105 with a max IT of 96 ms. The top 20 most intense ions were fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy of 32%, and the isolation window was 0.7 m/z. A dynamic exclusion time of 45 s was applied. Single-charged peaks and peaks with charges exceeding 6 were excluded from the data-dependent acquisition process.

Proteomic data processing and bioinformatics analysis

Raw mass spectrometry (MS) data were processed using Proteome Discoverer (PD) software (v. 2.4.0.305) and the built-in Sequest HT search engine. MS spectra were searched against the species-level UniProt FASTA database (uniprot-Human-9606-2020-10. fasta). Carbamidomethylation (C), TMTpro modification (K), and TMTpro modification (N-terminal) were applied as fixed modifications, while oxidation (M) and acetylation (protein N-terminal) were considered as variable modifications. Trypsin was used as the proteases, with a maximum of two missed cleavages allowed. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1% for both the peptide spectrum match (PSM) and peptide levels. Peptide identification was performed with an initial precursor mass deviation up to 10 ppm and a fragment mass deviation of 0.02 Da. Unique peptides and razor peptides were used for protein quantification, while total peptide amount was used for normalization. All other parameters were set to their default values. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the prcomp function in R. A heatmap was constructed to exhibit protein expression across different groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p < 0.01). Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were identified with log2foldchange (|log2FC|≥ 0.5) and p < 0.05.

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were performed on the DEPs using the Metascape web tool (https://metascape.org/) (Zhou et al. 2019).

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

The STRING database (https://string-db.org/) was employed to identify interactions among predicted and known proteins of DEPs. A PPI network was constructed using the STRING web tool (Szklarczyk et al. 2023). After network construction, visualization was performed using Cytoscape (v. 3.7.0) (Shannon et al. 2003). To identify functionally relevant modules within the PPI network, the molecular complex detection (MCODE) algorithm was applied with degree cutoff = 2, node score cutoff = 0.2, k-core = 2, and maximum depth = 100.

Immune-related and metabolism-related pathway analyses

Changes in immune- and metabolism-related gene sets were evaluated based on variations in protein expression using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) in the R “GSVA” package (v. 1.46.0). Significant immune cells (B cells, memory B cells, naïve B cells, activated B cells, natural killer cells, and plasma cells), and gene sets (angiogenesis and T cell infiltration 2) were analyzed across groups, and the results were visualized using violin plots.

Correlation analysis between clinical features and DEPs

Correlation analysis between clinical features and DEPs were performed using the psych (v. 2.3.9), reshape2 (v. 1.4.4), and pheatmap (v. 1.0.12) packages in R (v. 4.3.1). The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the relationship between clinical features and DEPs. Visualization of the correlation results were subsequently performed using the ggplot2 package (v 3.4.3) in R.

Statistical analysis

Clinical indicators were compared between two groups using t-tests, while one-way ANOVA was applied to assess differences in DEPs among the three groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a p-value < 0.01 was considered extremely significant.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population

Serum parameters, including low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (CHOL), triglycerides (TG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), fasting glucose (GLU), and blood pressure, were analyzed for all participants. The results revealed that the levels of LDL-C, CHOL, creatinine (Cr), calcium (Ca), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were lower in both the SIHD and CAC_SIHD groups compared with the control group, although these differences were not statistically significant. Notably, the BUN level in SIHD patients was significantly higher than that in the control group, while the GLU level in CAC_SIHD patients was significantly higher than that in the control group. No significant changes were observed for other indicators (Fig. 1A; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Serum parameters of the study population. LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, CHOL total cholesterol, TG triglycerides, BUN blood urea nitrogen, SBP systolic blood pressure, Cr creatinine, UA uric acid, Ca calcium, GLU fasting glucose, DBP diastolic blood pressure. Note: p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Table 1.

Baseline clinical statistics for SIHD, CAC_ SIHD, and control groups

| Variable | Control (n = 9) | SIHD (n = 6) | CAC_SIHD (n = 6) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender(male/female)a | 5/4 | 4/2 | 3/3 | 1 |

| Age(years)b | 57.44 ± 15.44 | 61.33 ± 17.44 | 62.33 ± 5.16 | 0.776 |

| CHOLb | 4.61 ± 1.05 | 3.80 ± 0.70 | 3.92 ± 1.36 | 0.303 |

| TGc | 1.75 ± 1.40 | 2.09 ± 0.965 | 1.55 ± 0.935 | 0.574 |

| LDL-Cb | 2.62 ± 0.723 | 2.11 ± 0.716 | 2.17 ± 0.914 | 0.384 |

| BUNb | 4.51 ± 0.941 | 6.92 ± 2.08 | 5.65 ± 2.59 | 0.074 |

| Crb | 73.89 ± 13.50 | 67.83 ± 11.41 | 69.33 ± 11.57 | 0.620 |

| UAc | 366.56 ± 66.23 | 404.50 ± 94.17 | 325.50 ± 73.33 | 0.152 |

| Cab | 2.35 ± 0.10 | 2.28 ± 0.08 | 2.29 ± 0.11 | 0.305 |

| GLUc | 4.94 ± 0.58 | 6.72 ± 2.13 | 7.37 ± 2.04 | 0.010 |

| SBP (mm Hg)b | 123.44 ± 8.46 | 132.83 ± 9.08 | 134.00 ± 16.28 | 0.163 |

| DBP (mm Hg)b | 82.44 ± 11.36 | 75.33 ± 11.69 | 78.33 ± 10.21 | 0.482 |

aFisher's exact test; bANOVA test; cKruskal–Wallis test

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Differential analysis revealed distinct protein expression patterns and pathway enrichment between the patient groups (SIHD and CAC_SIHD) and healthy controls

To explore changes in the proteome of SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients, we conducted differential proteomic analysis across the three groups. Principal component analysis (PCA) was able to separate the patient groups and the control group. In contrast, the SIHD and CAC_SIHD groups showed a certain degree of similarity, as indicated by their overlapping distributions (Fig. 2a). A total of 33 DEPs were detected, with the majority being upregulated in the patient groups as compared with the control group, such as complement pathway-related proteins C1QC, C1QA, and C1QB (Fig. 2b). Further analysis of the DEPs between the patient groups and the control group revealed 24 upregulated and 18 downregulated DEPs in the SIHD group, and 27 upregulated and 22 downregulated DEPs in the CAC_SIHD group, both compared with the controls (Fig. 2c). At the same time, the interaction networks of DEPs between the control and SIHD groups indicted that CRP, APOB, and APOH may serve as key proteins in SIHD (Fig. 2d), while CRP, APOB, and VWF were identified as critical proteins in CAC_SIHD (Fig. 2e). Subsequently, we performed KEGG analysis to identify enriched functional pathways in the patient groups. Compared with normal controls, both SIHD and CAC_SIHD exhibited proteins that were enriched in complement and coagulation cascades, as well as cholesterol metabolism (Fig. 2f, g). These findings suggest alterations in cholesterol metabolism in both SIHD and CAC_SIHD, potentially affecting blood cholesterol levels. In summary, our results highlight significant differences between the patient groups and controls, which may be associated with complement system activation and cholesterol metabolism.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the proteomic data for the SIHD, CAC_SIHD, and control groups. a Principal component analysis (PCA) of proteomic data for SIHD, CAC_SIHD, and Control groups. b Heatmap showing the expression of crucial proteins among the three groups, identified using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p < 0.01). c Volcano plot of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between the control and patient groups. Red color represents upregulation, while green represents downregulation. Screening criteria are |log2FC|≥ 0.5 and p < 0.05. d Interaction network of DEPs between the control and SIHD groups. The size of the circles represents the number of lines linked to each node. e Interaction network of DEPs between the control and CAC_SIHD groups. f KEGG functional analysis of DEPs identified between the control and SIHD groups. g KEGG pathway analysis of DEPs identified between the control and CAC_SIHD groups

Differential protein profiling and functional analysis between SIHD and CAC_SIHD

To investigate proteomic differences between SIHD and CAC_SIHD, PCA was performed, revealing a clear distinction between the two groups (Fig. 3a). Differential proteomic analysis showed that a substantial number of proteins were downregulated in SIHD patients, including APOA2 and RNASE1 (Fig. 3b). The expression profiling of the top 37 DEPs (Fig. 3c) further demonstrated that serum protein profiles in SIHD and CAC_SIHD were significantly different. Analysis of GO functional network enrichment revealed that these DEPs were closely related to processes such as negative regulation of cell population proliferation, reverse cholesterol transport, regulation of hydrolase activity, complement and coagulation cascades, complement system, NABA secreted factors, humoral immune response, and skeletal system development (Fig. 3d). We also constructed the interaction networks of DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD, obtaining six crucial sub-networks (Fig. 3e). In conclusion, our findings highlight disruptions in lipid metabolism and complement pathways in the serum of SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients, suggesting that altered lipid profiles and immune dysregulation may be significant risk factors.

Fig. 3.

Expression profiling and functional analysis of DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. a PCA results of proteome showing a substantial distinction between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. b Volcano plot demonstrating DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. c Heatmap showing the expression of top 37 DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. d Gene oncology (GO) functional network enrichment of DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. e Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) identified six crucial sub-networks between SIHD and CAC_SIHD

Trend analysis identified distinct clusters across the three groups

K-means cluster analysis was performed to elucidate the roles and changing patterns of serum proteins in SIHD and CAC_SIHD. Initially, the proteins were grouped into six clusters, which were further refined into five major clusters based on their trend patterns (Fig. 4a–f). Both Cluster 1 and Cluster 4 experienced downregulation in the CAC and SIHD_CAC groups. However, the SIHD group displayed a relatively higher z-score in Cluster 1, indicating a trend toward less pronounced downregulation compared with that in Cluster 4. In contrast, Cluster 4 did not show a similar elevated trend in the SIHD group, suggesting a more uniform downregulation across groups. The two clusters were primarily associated with complement and coagulation cascades, cholesterol metabolism, and focal adhesion pathways (Fig. 4a, b). In Cluster 2, protein expression decreased sharply in CAC_SIHD, followed by a rebound in SIHD. This cluster was primarily associated with the TGF-beta signaling pathway and cholesterol metabolism (Fig. 4c). In Cluster 5 protein expression peaked sharply in CAC_SIHD and then decreased in SIHD. This cluster was primarily associated with phagosome and protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 4d). Cluster 3 exhibited a dynamic expression pattern, characterized by pronounced upregulation in SIHD, followed by partial downregulation in CAC_SIHD. This cluster was predominantly linked to phagosome, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, and cholesterol metabolism pathways (Fig. 4e) In contrast, protein expression in Cluster 6 showed a steady decline across all groups, starting at high levels in the control group, decreasing in CAC_SIHD, and dropping further in SIHD. This cluster was mainly associated with proteasome and focal adhesion pathways (Fig. 4f). Cholesterol metabolism, as well as complement and coagulation cascades, were found to be enriched in all five clusters. We further analyzed alterations in lipid- and immune-related proteins. Heatmap analysis revealed distinct expression patterns, with a higher number of immune-related proteins showing upregulation in the SIHD group (Fig. 4g, h). This observation indicates that while there were similarities in expression trends between the SIHD and CAC groups, there were also notable differences, particularly in the regulation of immune-related proteins.

Fig. 4.

K-means cluster analysis and functional analysis of all proteins across the three groups. a–f The left panel displays the k-means cluster analysis of DEPs, highlighting modules with markedly distinct patterns. The right panel shows the results of KEGG enrichment analysis. g Heatmap illustrating the proteomic profiles associated with lipid metabolism across groups. h Heatmap demonstrating the proteomic profiles associated with immune responses across groups

ssGSEA detected distinct immune responses in SHID and CAC_SIHD patients

To explore alterations in immune responses in SIHD and CAC_SIHD, alterations in immune-related gene sets were assessed based on changes in protein expression patterns. The results showed that natural killer cells, plasma cells, macrophages, and T cell infiltration 2 were activated in both SIHD and CAC_SIHD. However, T follicular helper cells and B cells (naive B cells, memory B cells, and activated B cell) were inhibited, with a dramatic reduction in central-memory CD8 + T cell infiltration in CAC_SIHD. Moreover, the ssGSEA score for angiogenesis showed an increasing tendency in both SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients (Fig. 5a, b). These results suggest that SIHD and CAC_SIHD were characterized by an increased presence of T cells and natural killer cells, along with a reduced presence in B cells.

Fig. 5.

SHID and CAC_SIHD patients exhibited distinct immune responses. a Heatmap of immune-related processes and cell types based on single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA). b Violin plots of specific immune cell subsets

Metabolic alterations in SIHD and CAC_SIHD

To understand the metabolic alterations associated with SIHD and CAC_SIHD, we explored the differences in metabolism-related pathways among the groups. ssGSEA revealed disparities among the SIHD, CAC_SIHD, and control groups. Glycosphosphatidylinositol and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis were found to be enriched in SIHD and CAC_SIHD. SIHD-related proteins were predominantly engaged in fructose and mannose metabolism. In contrast, CAC_SIHD was associated with metabolic pathways such as glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis, pyruvate metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, propanoate metabolism, ether lipid metabolism, glycosaminoglycan degradation, and glycosphingolipid biosynthesis, indicating that patients in this group exhibited activated lipid metabolism (Fig. 6a). The enrichment of the top four significantly altered metabolism pathways were investigated, namely cysteine and methionine metabolism, nicotinamide adenine metabolism, retinol metabolism, and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis. Among these, cysteine and methionine metabolism, as well as terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, were downregulated, while nicotinamide adenine metabolism and retinol metabolism were upregulated in SIHD and CAC_SIHD compared with the control group (Fig. 6b). The aberrant enrichment of these metabolic pathways may suggest the presence of severe lipid metabolic disturbances in CAC.

Fig. 6.

Metabolic dynamics analysis of SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients. a Metabolic profiles in control, SIHD, and CAC_SIHD groups based on ssGSEA. b Top four significantly altered metabolic pathways identified via ANOVA

To identify candidate proteins of CAC, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed on the DEPs between SIHD and CAC_SIHD. Seven proteins (RNASE1, MSLN, LUM, PSAP, NBL1, RNASE4, and CFP) demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 0.6, indicating potential discriminative power (Fig. 7a). Among these proteins, RNASE1 and MSLN emerged as potential predictive indicators for the early detection and diagnosis of CAC in SIHD patients. Next, we examined the expression of these potential indicators and found that they were downregulated in CAC_SIHD patients (Fig. 7b). Our results revealed that the decreased levels of these proteins correlated with CAC, suggesting that they may play a role in the pathophysiological processes underlying CAC development.

Fig. 7.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and evaluation of the expression of candidate proteins. a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves depicting the diagnostic performance of seven proteins as potential predictive indicators in discriminating CAC in SIHD patients. b Relative expression of the seven proteins in SIHD and CAC_SIHD group

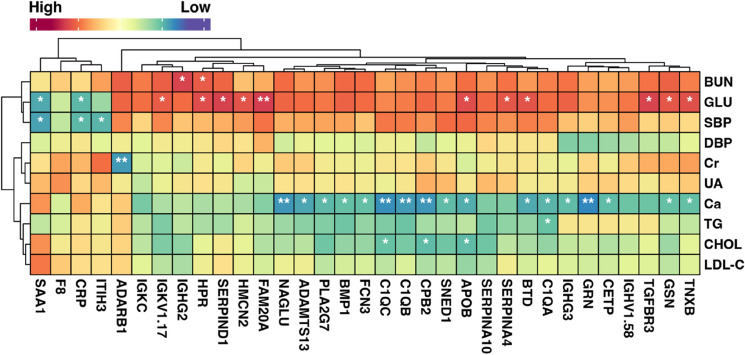

Correlation analysis between clinical characteristics and crucial proteins

We then conducted Pearson correlation analysis to explore the relationship between clinical parameters and key DEPs. The results demonstrated negative correlations between GLU and both SAA1and CRP. Conversely, GLU showed positive correlations with 11 proteins (IGKV1.17, HPR, SERPIND1, HMCN2, FAM20A, APOB, SERPINA4, BTD, TGFBR3, GSN, and TNXB), with FAM20A displaying a highly significant correlation with GLU. Furthermore, Ca was significantly negatively correlated with 17 proteins (NAGLU, ADAMTS13, PLA2G7, BMP1, FCN3, C1QC, C1QB, CPB2, SNED1, APOB, BTD, C1QA, IGHG3, GRN, CETP, GSN, and TNXB), while CHOL was negatively correlated with C1QC, CPB2, and APOB. TG was negatively correlated with C1QA. These proteins were likely to play crucial roles in the development of SIHD and CAC (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Pearson correlation analysis between clinical characteristics and crucial DEPs with p < 0.01 by ANOVA

Discussion

The majority of prior investigations on SIHD or CAC have been conducted using animal models, with relatively few studies involving clinical samples (Milanese et al. 2020; Osei et al. 2021; Egaña-Gorroño et al. 2020). In this study, we examined the serum proteome of SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients, identifying dysregulations in complement mechanisms and lipid metabolism in patients with SIHD and CAC_SIHD. Our investigation revealed potential pathogenic processes underlying CAC, and highlighted potential predictive indicators in the serum.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the innate immune system plays a crucial role in inducing cardiovascular calcification through inflammatory responses, with complement proteins constituting a potent cascade in this process (Ekdahl et al. 2017; Passos et al. 2020; Broeders et al. 2022). However, whether the activation of complement system promotes the pathophysiology of arterial calcification remains unclear. Typically, the complement system is regulated through three main pathways: the classical pathway, the lectin pathway, and the alternate pathway. Recent proteomics investigations have revealed that the complement C5 expression is elevated in CAC tissue and subclinical atherosclerotic tissue. Moreover, complement pathway-related proteins, such as C1QC, C1QB, and C1QA were significantly upregulated in both SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-3 (CTRP3) identified as an adipokine that plays crucial roles in the cardiovascular system (Schaffler and Buechler 2012). It exerts anti-inflammatory effects in adipocytes and monocytes (Kopp et al. 2010) and has been shown to promote vascular calcification by accelerating phosphate-induced osteogenic transition of VSMCs through the ROS-ERK1/2-Runx2 signaling pathway (Zhou et al. 2014). We hypothesized that the upregulation of C1Q proteins may facilitate and drive calcification through modulation of CTRP3. Further, our study revealed enriched cholesterol metabolism in SIHD and CAC_SIHD. HDL-C has been inversely associated with the risk of CAD (Gordon et al. 1977; Sharrett et al. 2001) and low HDL-C levels are commonly observed in patients with CAD (Genest et al. 1993). Consequently, the imbalance in cholesterol metabolism, characterized by increased LDL-C and decreased HDL-C, may contribute to the increased risk of CAC.

Immune system activation or dysregulation is a major factor in the development and progression of various cardiovascular diseases. CAD is a manifestation of atherosclerosis (Lopez et al. 2006; Stary et al. 1995). During the early stages of atherosclerosis, T cells are involved in both the initiation and progression of the disease, while in more advanced stages, they contribute to the destabilization of atherosclerotic lesions (Hansson et al. 1989; Jamila et al. 2006). In our study, increased levels of T cells and natural killer cells were observed in patients with SIHD or CAC_SIHD, implying that these immune cells may contribute to the progression of these clinical conditions.

The calcium-dependent binding of CRP to phosphorylcholine stimulates agglutination, bacterial capsular enlargement, phagocytosis, and complement fixation, all of which are key activities in host defense (Nehring and Patel 2017; Mosquera-Sulbaran et al. 2021; Pope and Choy 2021). CRP is also a significant promoter of vascular inflammation (Laura et al. 2019), acting as a negative predictor of cardiovascular disease (Ding et al. 2015). Elevated CRP levels are associated with increased calcification and higher cardiovascular event-related mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (Laura et al. 2019). VWF is a protein that plays a pivotal role in blood coagulation. Previous studies have indicated the potential involvement of VWF in the process of atherogenesis. In vitro, LDL increases the expression of VWF on the surface of endothelial cells, which may contribute to atherogenesis by promoting platelet adhesion, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. Additionally, various factors that stimulate VWF secretion are implicated in atherogenesis, suggesting a potential role for VWF in plaque formation and instability (Karin et al. 2012; Vischer 2006). Furthermore, smooth muscle cells are a major constituent of atherosclerotic plaques, and VWF stimulates the proliferation of mouse aortic smooth muscle cells in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Qin et al. 2003). As CAC is closely related to atherosclerosis and serves as a characteristic feature of atherosclerotic lesions (Alexopoulos and Raggi 2009), VWF may play a role in the formation of CAC. APOB is an important apolipoprotein involved in cholesterol and lipid metabolism. The level of APOB, rather than LDL-C, is found to be associated with CAC scores in white patients with type 2 diabetic, which may be particularly useful in assessing atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular risk in this population (Martin et al. 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that CRP, VWF, and APOB may play crucial roles in the formation and progression of CAC, making them potential adjunctive factors in the clinical assessment of CAC.

In this investigation, seven potential serum factors (RNASE1, MSLN, LUM, PSAP, NBL1, RNASE4, and CFP) were identified in SIHD and CAC_SIHD patients. RNASE1 acts as a protective factor for vascular homeostasis, and is known to be repressed by persistent inflammation, which is linked to the development of vascular pathologies (Laakmann et al. 2023). The overexpression of MSLN can inhibit cell apoptosis and promote cell proliferation, migration and metastasis, potentially influencing the CAC process by regulating the biological functions of endothelial cells (Bharadwaj et al. 2011; Coelho et al. 2020). Therefore, RNASE1 and MSLN may be possible factors for the early detection and diagnosis of CAC.

In conclusion, our study identified alterations in the serum proteome of patients with SIHD and CAC_SIHD, which were strongly linked to the underlying disease manifestations and clinical observations. The pathways involved in complement and coagulation cascades, along with cholesterol metabolism, appear to play a key role in the pathogenesis of CAC. Moreover, the increased immune infiltration of T cells and natural killer cells in SIHD and CAC_SIHD may contribute to the progression of CAC. Additionally, our findings suggest that RNASE1 and MSLN may serve as candidate protein indicators for CAC. These identified indicators and metabolic pathways may offer valuable insights for improving diagnostic capabilities and highlighting potential therapeutic targets. Future research with larger samples could further investigate the mechanistic roles of these proteins, which may contribute to the development of personalized interventions and enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions between proteins and patients with SIHD or CAC_SIHD.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Haiyan Wu and Mingjie Pang; Data curation, Haoqinag Chen; Formal analysis, Haoqiang Chen and Ke Zhuang; Funding acquisition, Xiaoxue Ding; Methodology, Haiyan Wu and Mingjie Pang; Project administration, Hong Zhang and Yan Zhao; Resources, Hong Zhang; Supervision, Xiaoxue Ding; Validation, Yan Zhao; Visualization, Haoqinag Chen; Writing—original draft, Haiyan Wu and Mingjie Pang; Writing—review & editing, Ke Zhuang, Hong Zhang, Yan Zhao and Xiaoxue Ding.

Funding

This study was supported by Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology—Kunming Medical University Joint Special Project on Applied Basic Research (Grant No. 202201AY070001-257).

Data availability

The data are available upon request from corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was granted with the approval of the ethical committee of the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (2016LH083) and conform the relevant ethical guidelines for human and animal research. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alexopoulos N, Raggi P (2009) Calcification in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 6(11):681–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshian Nik A, Hutcheson JD, Aikawa E (2017) Extracellular vesicles as mediators of cardiovascular calcification. Front Cardiovasc Med 4:78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak T, Tanwar VS, Bhardwaj G, Bhardwaj N, Ahmad S, Garg GVS, Karthikeyan G, Seth S, Sengupta S (2016) Plasma proteomic analysis of stable coronary artery disease indicates impairment of reverse cholesterol pathway. Sci Rep 6:28042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj U, Marin-Muller C, Li M, Chen C, Yao Q (2011) Mesothelin confers pancreatic cancer cell resistance to TNF-α-induced apoptosis through Akt/PI3K/NF-κB activation and IL-6/Mcl-1 overexpression. Mol Cancer 10:106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaha M, Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Khosa F, Rumberger JA, Berman D, Callister T, Raggi P, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K (2009) Absence of coronary artery calcification and all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2(6):692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman MAH, McNally EM (2012) Genetic pathways of vascular calcification. Trends Cardiovasc Med 22(4):93–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeders W, Bekkering S, El Messaoudi S, Joosten LA, van Royen N, Riksen NP (2022) Innate immune cells in the pathophysiology of calcific aortic valve disease: lessons to be learned from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease? Basic Res Cardiol 117(1):1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu-Chun Z, Xiangdong K, GuangQuan Q, LongWei L, Lian M (2022) Proteomic analysis of serum proteins from patients with severe coronary artery calcification. Rev Cardiovasc Med 6:66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budoff M (2006) Aged garlic extract retards progression of coronary artery calcification. J Nutr 136(3):741S-744S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo M, Witasp A, Qureshi A, Laguna-Fernandez A, Brismar T, Stenvinkel P, Bäck M (2019) Chemerin inhibits vascular calcification through ChemR23 and is associated with lower coronary calcium in chronic kidney disease. J Intern Med 286(4):449–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho R, Ricardo S, Amaral AL, Huang Y-L, Nunes M, Neves JP, Mendes N, López MN, Bartosch C, Ferreira V et al (2020) Regulation of invasion and peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer by mesothelin manipulation. Oncogenesis 9(6):61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Min W, Dongfang S, Chang-jiang H, Xinrui L, Yuan Z, Gang H, Wenhua L (2015) Abstract P255: body mass index, C-reactive protein and mortality among coronary artery disease patients. Circulation 6:66 [Google Scholar]

- Egaña-Gorroño L, López-Díez R, Yepuri G, Ramirez LS, Reverdatto S, Gugger PF, Shekhtman A, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM (2020) Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities in diabetes and cardiovascular disease: insights from human subjects and animal models. Front Cardiovasc Med 7:37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl KN, Soveri I, Hilborn J, Fellström B, Nilsson B (2017) Cardiovascular disease in haemodialysis: role of the intravascular innate immune system. Nat Rev Nephrol 13(5):285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genest J Jr, Bard JM, Fruchart JC, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ (1993) Familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia in premature coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb 13(12):1728–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR (1977) High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Am J Med 62(5):707–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Lau E, Varshney R, Hulten EA, Cheezum M, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, Wong ND, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ (2017) The identification of calcified coronary plaque is associated with initiation and continuation of pharmacological and lifestyle preventive therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 10(8):833–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK, Holm J, Jonasson L (1989) Detection of activated T lymphocytes in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Am J Pathol 135(1):169–175 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamila K-L, Giuseppina C, Emilie G, Tupin E, Anh-Thu G, Bruno P, Mitchell K, José LC, David K, Srini VK et al (2006) The proatherogenic role of T cells requires cell division and is dependent on the stage of the disease. Arterioscler Thrombos Vasc Biol 6:66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin PMvG, Tuinenburg A, Emma MS, Roger EGS (2012) Von Willebrand factor deficiency and atherosclerosis. Blood Rev 6:66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A, Bala M, Buechler C, Falk W, Gross P, Neumeier M, Scholmerich J, Schaffler A (2010) C1q/TNF-related protein-3 represents a novel and endogenous lipopolysaccharide antagonist of the adipose tissue. Endocrinology 151(11):5267–5278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyavar M, Alemzadeh-Ansari MJ (2022) Chapter 24—stable ischemic heart disease. In: Maleki M, Alizadehasl A, Haghjoo M (eds) Practical cardiology, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 429–453 [Google Scholar]

- Laakmann K, Eckersberg JM, Hapke M, Wiegand M, Bierwagen J, Beinborn I, Preußer C, Pogge von Strandmann E, Heimerl T, Schmeck B et al (2023) Bacterial extracellular vesicles repress the vascular protective factor RNase1 in human lung endothelial cells. Cell Commun Signal 21(1):111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura H, Trang TDL, Beate B, Jaber M, Markus PS, Sebastian B, Florian L, Burkert P, Andreas P, Kai-Uwe E et al (2019) Impact of C-reactive protein on osteo-/chondrogenic transdifferentiation and calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells. Aging 6:66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Li S, Wang Y-J, Wang Y, Zhong J-Y, He J-Y, Cui X-J, Zhan J-K, Liu Y-S (2019) Exosomal Notch3 from high glucose-stimulated endothelial cells regulates vascular smooth muscle cells calcification/aging. Life Sci 232:116582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey ML, Mayr M, Gomes AV, Delles C, Arrell DK, Murphy AM, Lange RA, Costello CE, Jin YF, Laskowitz DT et al (2015) Transformative impact of proteomics on cardiovascular health and disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 132(9):852–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang T, Yan J, Jiagbogu N, Heideman DA, Canfield AE, Alexander MY (2011) HGF/c-Met signalling promotes Notch3 activation and human vascular smooth muscle cell osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Atherosclerosis 219(2):440–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Li J, Liu H, Tang Y, Zhan Q, Lai W, Ao L, Meng X, Ren H, Xu D (2019) The intestinal microbiota associated with cardiac valve calcification differs from that of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 284:121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (2006) Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367(9524):1747–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud AM, Jones AM, Sidgwick GP, Arafat AM, Alexander YM, Wilkinson FL (2019) Small molecule glycomimetics inhibit vascular calcification via c-Met/Notch3/HES1 signalling. Cell Physiol Biochem 53(2):323–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SS, Qasim AN, Mehta NN, Wolfe M, Terembula K, Schwartz S, Iqbal N, Schutta M, Bagheri R, Reilly MP (2009) Apolipoprotein B but not LDL cholesterol is associated with coronary artery calcification in type 2 diabetic whites. Diabetes 58(8):1887–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López D, Roldan-Montero R, García-Marqués F, Nuñez E, Jorge I, Camafeita E, Minguez P, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, López-Melgar B, Lara-Pezzi E (2020) Complement C5 protein as a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 75(16):1926–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Members WC, Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, Bittner V, Brewer LC, Demeter SH, Dixon DL, Fearon WF, Hess B (2023) 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 82(9):833–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanese G, Silva M, Ledda RE, Goldoni M, Nayak S, Bruno L, Rossi E, Maffei E, Cademartiri F, Sverzellati N (2020) Validity of epicardial fat volume as biomarker of coronary artery disease in symptomatic individuals: results from the ALTER-BIO registry. Int J Cardiol 314:20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera-Sulbaran JA, Pedreañez A, Carrero Y, Callejas D (2021) C-reactive protein as an effector molecule in Covid-19 pathogenesis. Rev Med Virol 31(6):e2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehring SM, Patel B (2017) C reactive protein (CRP)

- Newman AB, Naydeck BL, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Feldman A, Edmundowicz D, Kuller LH (2001) Coronary artery calcification in older adults to age 99: prevalence and risk factors. Circulation 104(22):2679–2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei AD, Mirbolouk M, Berman D, Budoff MJ, Miedema MD, Rozanski A, Rumberger JA, Shaw L, Al Rifai M, Dzaye O (2021) Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium score, area, and density among individuals on statin therapy vs.non-users: the coronary artery calcium consortium. Atherosclerosis 316:79–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka F, Sakakura K, Yahagi K, Joner M, Virmani R (2014) Has our understanding of calcification in human coronary atherosclerosis progressed? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34(4):724–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panh L, Lairez O, Ruidavets J-B, Galinier M, Carrié D, Ferrières J (2017) Coronary artery calcification: from crystal to plaque rupture. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 110(10):550–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos LS, Lupieri A, Becker-Greene D, Aikawa E (2020) Innate and adaptive immunity in cardiovascular calcification. Atherosclerosis 306:59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope JE, Choy EH (2021) C-reactive protein and implications in rheumatoid arthritis and associated comorbidities. In: Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. Elsevier, pp 219–229 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Qianqian W, Xin Z, Xiaoping P (2011) Proteome analysis of the left ventricle in the vitamin D3 and nicotine-induced rat vascular calcification model. J Proteomics 6:66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Impeduglia T, Schaffer P, Dardik H (2003) Overexpression of von Willebrand factor is an independent risk factor for pathogenesis of intimal hyperplasia: preliminary studies. J Vasc Surg 37(2):433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler A, Buechler C (2012) CTRP family: linking immunity to metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23(4):194–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13(11):2498–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA, Heiss G, Sorlie PD, Catellier D, Patsch W (2001) Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study G: Coronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, lipoprotein(a), apolipoproteins A-I and B, and HDL density subfractions: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 104(10):1108–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW (1995) A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 92(5):1355–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT, Pyysalo S et al (2023) The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 51(D1):D638–D646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer UM (2006) von Willebrand factor, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. J Thromb Haemost 4(6):1186–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MC, Murchison JT, Edwards LD, Agustí A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, Lomas DA (2014) Coronary artery calcification is increased in patients with COPD and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Thorax 69(8):718–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yejin M, Yasuyuki H, Frances W, Candace MH, Aaron RF, Josef C, Matthew JB, Michael JB, Kuni M (2022) Abstract MP61: 1-year prognosis by coronary artery and extra-coronary calcification in the 75-and-older population. Circulation 6:66 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang K, Huang F, Feng W, Chen J, Zhang H, Wang J, Luo P, Huang H (2018) Exosomes, the message transporters in vascular calcification. J Cell Mol Med 22(9):4024–4033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Kong X, Qiu G, Li L, Ma L (2022) Proteomic analysis of serum proteins from patients with severe coronary artery calcification. Rev Cardiovasc Med 23(7):229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wang JY, Feng H, Wang C, Li L, Wu D, Lei H, Li H, Wu LL (2014) Overexpression of c1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-3 promotes phosphate-induced vascular smooth muscle cell calcification both in vivo and in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34(5):1002–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C, Chanda SK (2019) Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun 10(1):1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu QM, Hsu Y-HH, Lassen FH, MacDonald BT, Stead S, Malolepsza E, Kim A, Li T, Mizoguchi T, Schenone M et al (2024) Protein interaction networks in the vasculature prioritize genes and pathways underlying coronary artery disease. Commun Biol 7(1):87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request from corresponding author.