Abstract

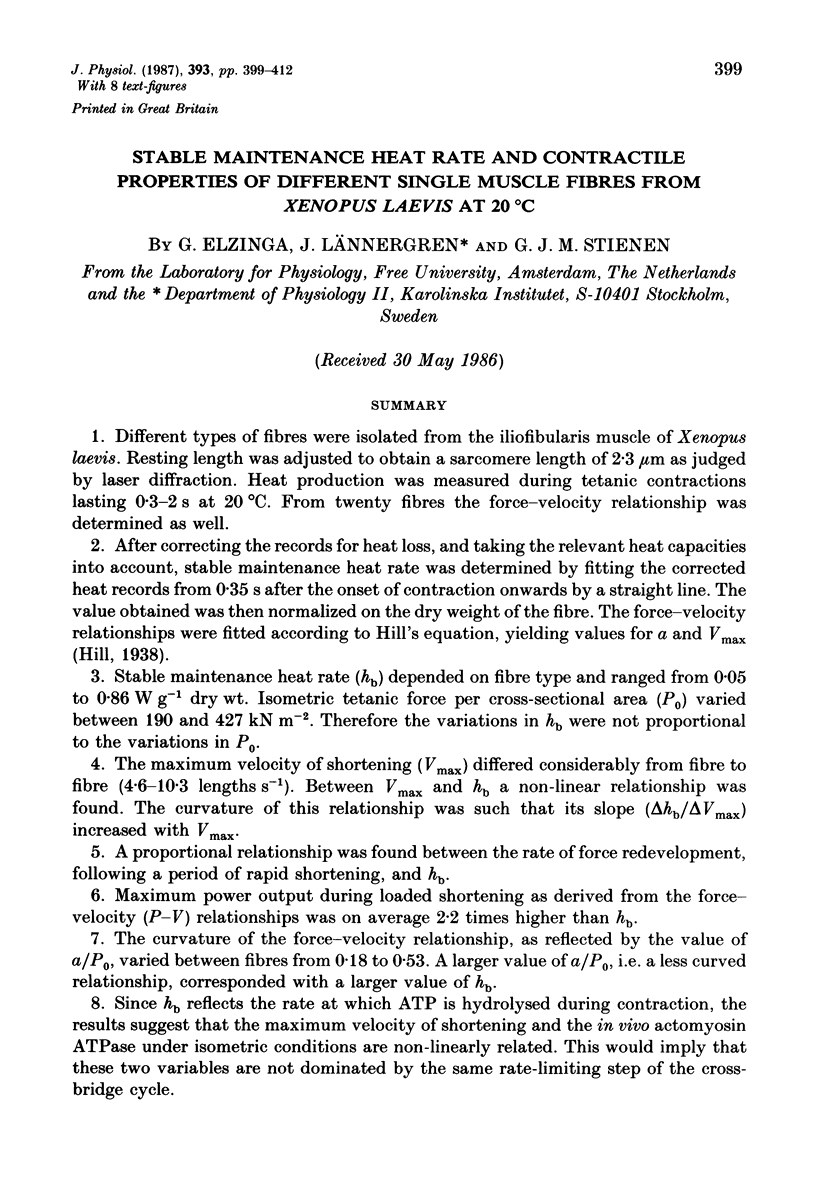

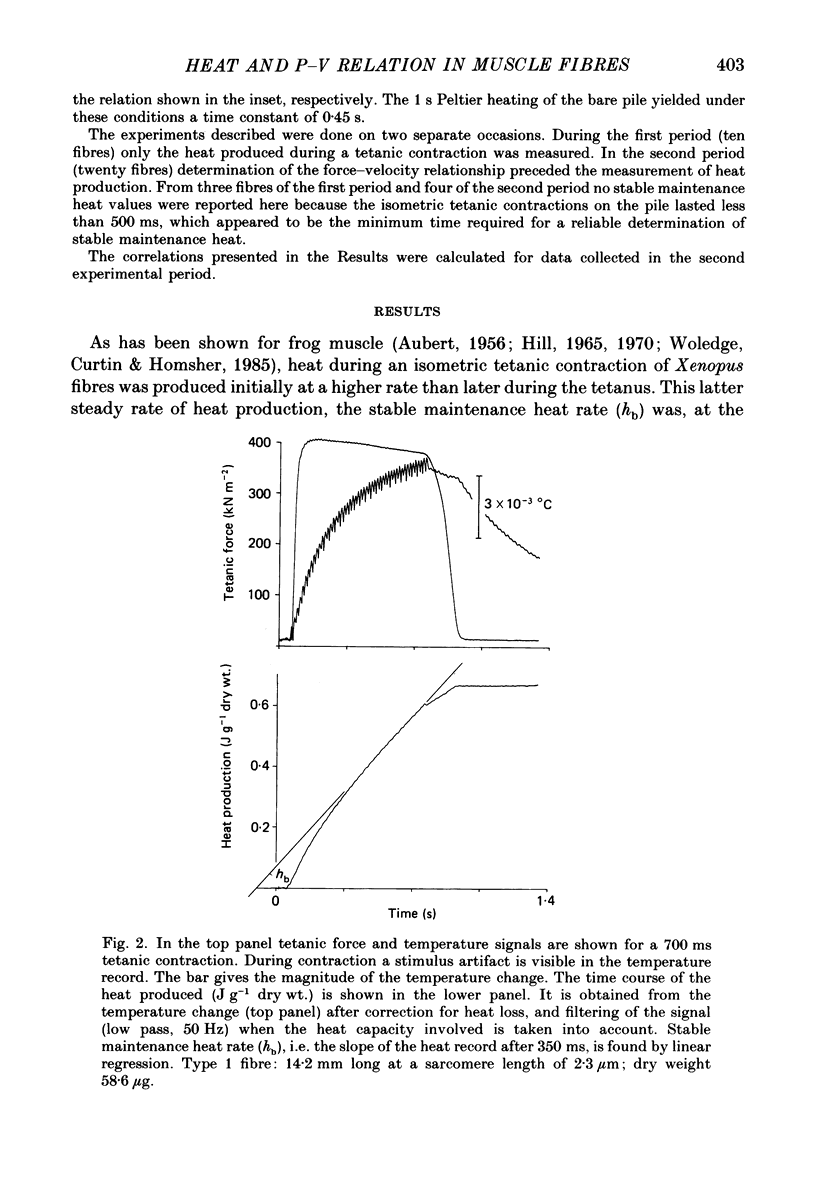

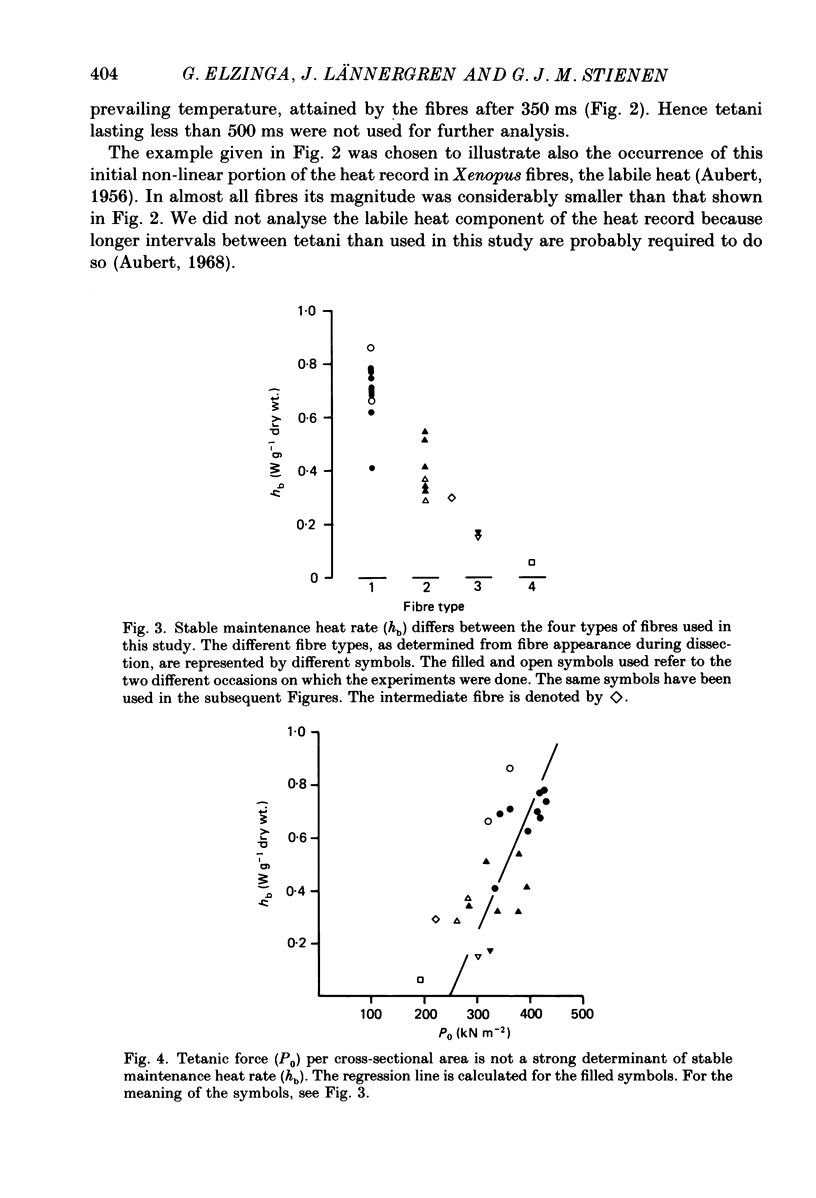

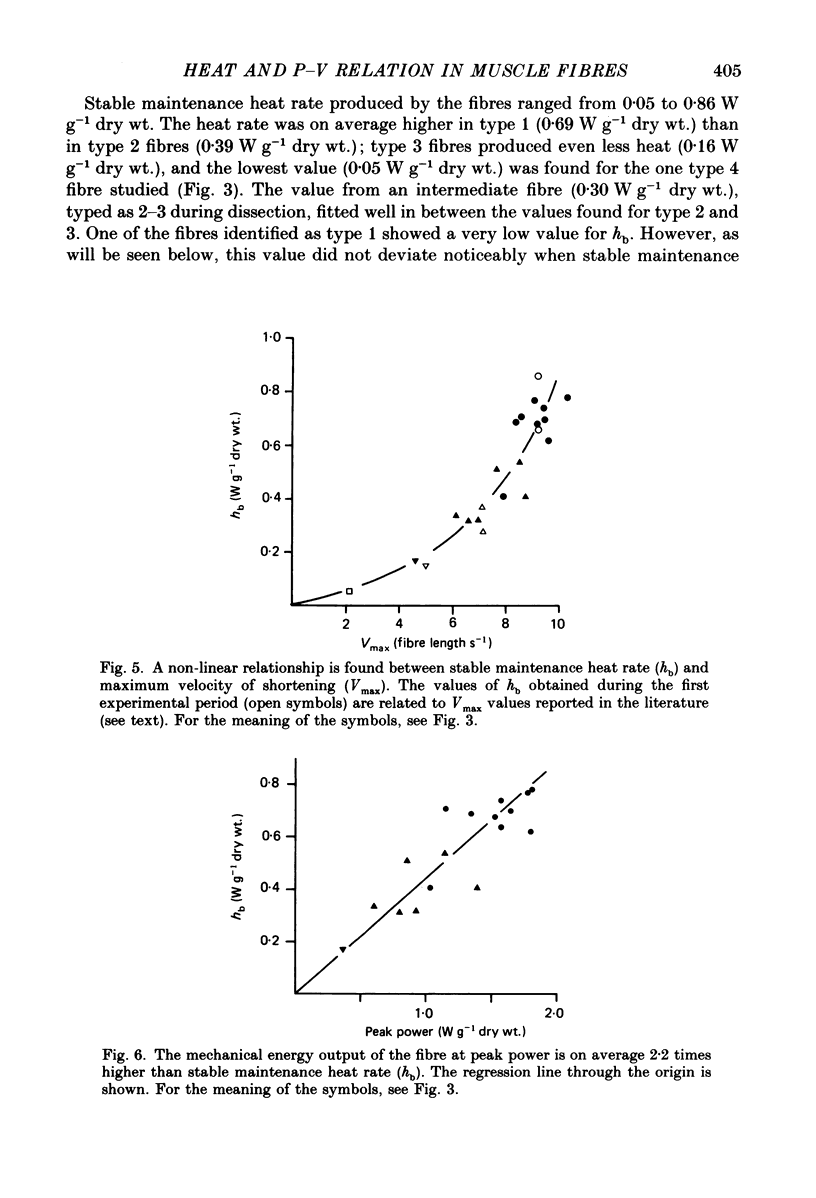

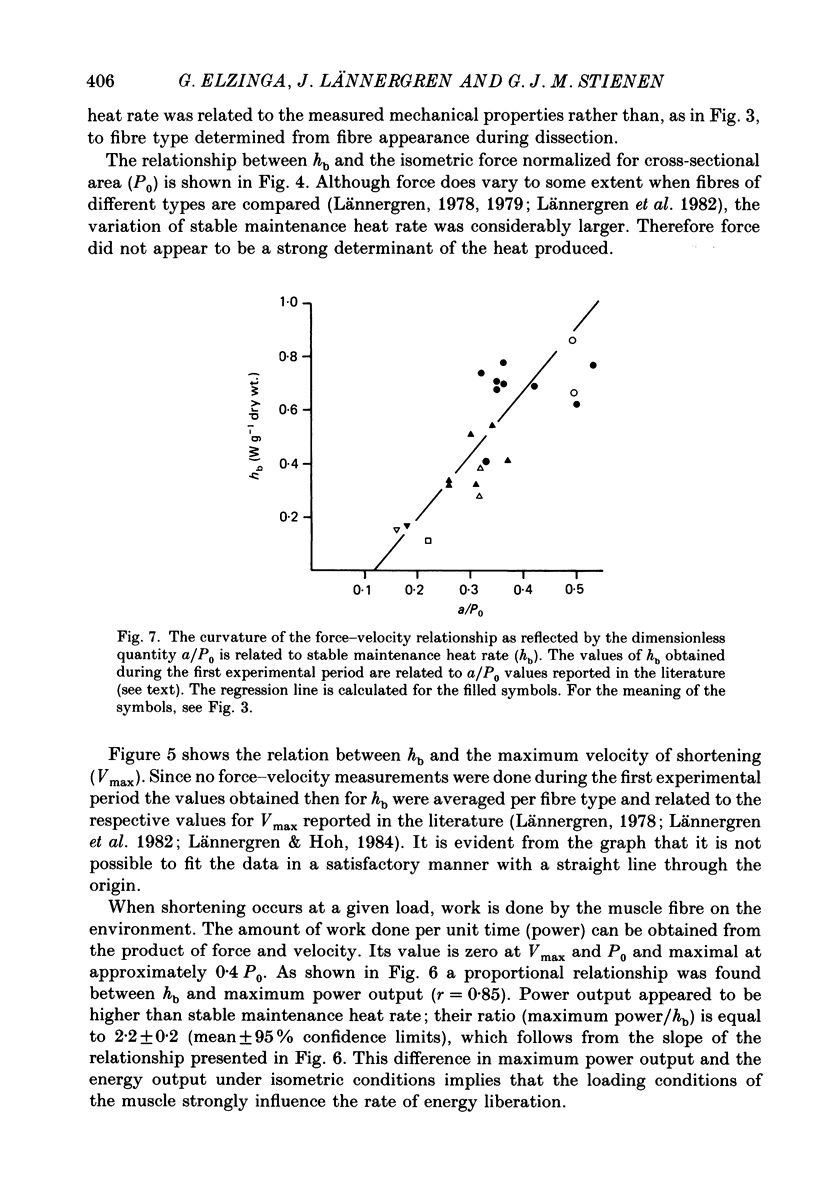

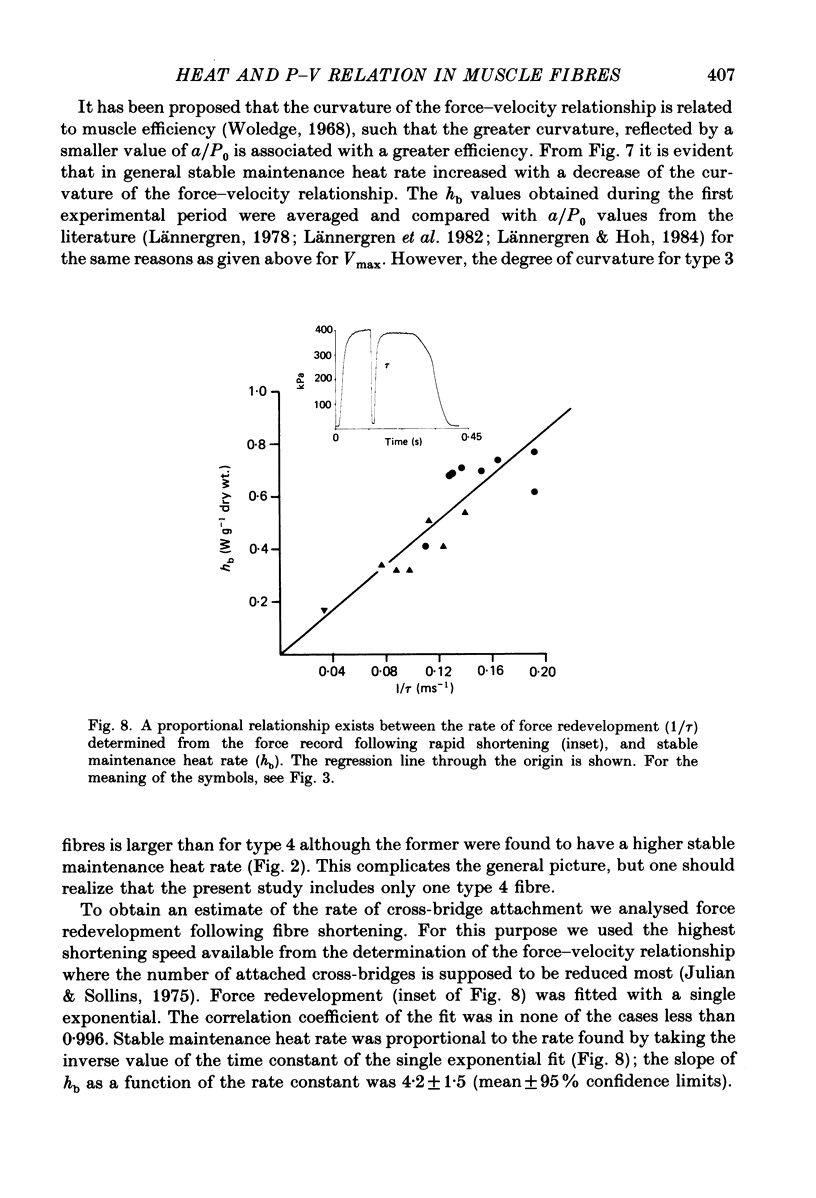

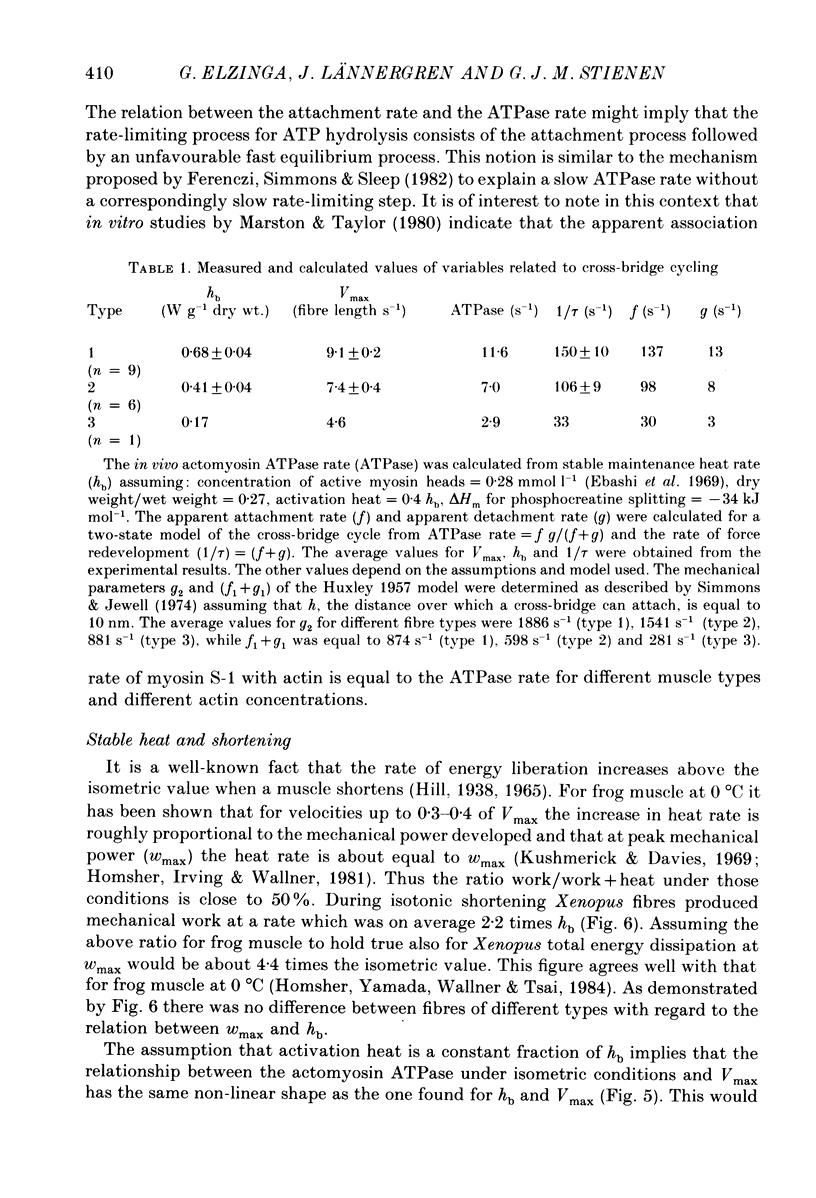

1. Different types of fibres were isolated from the iliofibularis muscle of Xenopus laevis. Resting length was adjusted to obtain a sarcomere length of 2.3 microns as judged by laser diffraction. Heat production was measured during tetanic contractions lasting 0.3-2 s at 20 degrees C. From twenty fibres the force-velocity relationship was determined as well. 2. After correcting the records for heat loss, and taking the relevant heat capacities into account, stable maintenance heat rate was determined by fitting the corrected heat records from 0.35 s after the onset of contraction onwards by a straight line. The value obtained was then normalized on the dry weight of the fibre. The force-velocity relationships were fitted according to Hill's equation, yielding values for a and Vmax (Hill, 1938). 3. Stable maintenance heat rate (hb) depended on fibre type and ranged from 0.05 to 0.86 W g-1 dry wt. Isometric tetanic force per cross-sectional area (P0) varied between 190 and 427 kN m-2. Therefore the variations in hb were not proportional to the variations in P0. 4. The maximum velocity of shortening (Vmax) differed considerably from fibre to fibre (4.6-10.3 lengths s-1). Between Vmax and hb a non-linear relationship was found. The curvature of this relationship was such that its slope (delta hb/delta Vmax) increased with Vmax. 5. A proportional relationship was found between the rate of force redevelopment, following a period of rapid shortening, and hb. 6. Maximum power output during loaded shortening as derived from the force-velocity (P-V) relationships was on average 2.2 times higher than hb. 7. The curvature of the force-velocity relationship, as reflected by the value of a/P0, varied between fibres from 0.18 to 0.53. A larger value of a/P0 i.e. a less curved relationship, corresponded with a larger value of hb. 8. Since hb reflects the rate at which ATP is hydrolysed during contraction, the results suggest that the maximum velocity of shortening and the in vivo actomyosin ATPase under isometric conditions are non-linearly related. This would imply that these two variables are not dominated by the same rate-limiting step of the cross-bridge cycle.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brenner B., Eisenberg E. Rate of force generation in muscle: correlation with actomyosin ATPase activity in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 May;83(10):3542–3546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bárány M. ATPase activity of myosin correlated with speed of muscle shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1967 Jul;50(6 Suppl):197–218. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin N. A., Howarth J. V., Rall J. A., Wilson M. G., Woledge R. C. Absolute values of myothermic measurements on single muscle fibres from frog. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1986 Aug;7(4):327–332. doi: 10.1007/BF01753653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin N. A., Howarth J. V., Woledge R. C. Heat production by single fibres of frog muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1983 Apr;4(2):207–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00712031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin N. A., Woledge R. C. Energy changes and muscular contraction. Physiol Rev. 1978 Jul;58(3):690–761. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebashi S., Endo M., Otsuki I. Control of muscle contraction. Q Rev Biophys. 1969 Nov;2(4):351–384. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500001190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi M. A., Simmons R. M., Sleep J. A. General considerations of cross-bridge models in relation to the dependence on MgATP concentration of mechanical parameters of skinned fibers from frog muscles. Soc Gen Physiol Ser. 1982;37:91–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd K., Smith I. C. The mechanical and thermal properties of frog slow muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1971 Mar;213(3):617–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUXLEY A. F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsher E., Irving M., Wallner A. High-energy phosphate metabolism and energy liberation associated with rapid shortening in frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1981 Dec;321:423–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsher E., Kean C. J. Skeletal muscle energetics and metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 1978;40:93–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.40.030178.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsher E., Yamada T., Wallner A., Tsai J. Energy balance studies in frog skeletal muscles shortening at one-half maximal velocity. J Gen Physiol. 1984 Sep;84(3):347–359. doi: 10.1085/jgp.84.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J., Sollins M. R. Variation of muscle stiffness with force at increasing speeds of shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1975 Sep;66(3):287–302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick M. J., Davies R. E. The chemical energetics of muscle contraction. II. The chemistry, efficiency and power of maximally working sartorius muscles. Appendix. Free energy and enthalpy of atp hydrolysis in the sarcoplasm. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1969 Dec 23;174(1036):315–353. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1969.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lännergren J. An intermediate type of muscle fibre in Xenopus laevis. Nature. 1979 May 17;279(5710):254–256. doi: 10.1038/279254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lännergren J., Hoh J. F. Myosin isoenzymes in single muscle fibres of Xenopus laevis: analysis of five different functional types. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1984 Sep 22;222(1228):401–408. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lännergren J., Lindblom P., Johansson B. Contractile properties of two varieties of twitch muscle fibres in Xenopus laevis. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982 Apr;114(4):523–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lännergren J. The force-velocity relation of isolated twitch and slow muscle fibres of Xenopus laevis. J Physiol. 1978 Oct;283:501–521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston S. B., Taylor E. W. Comparison of the myosin and actomyosin ATPase mechanisms of the four types of vertebrate muscles. J Mol Biol. 1980 Jun 5;139(4):573–600. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Luhr G., Trefry J., Alpert N. R. Metal-film thermopiles for use with rabbit right ventricular papillary muscles. Am J Physiol. 1977 Nov;233(5):C146–C156. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.233.5.C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. S., Ovalle W. K., Jr Varieties of fast and slow extrafusal muscle fibres in amphibian hind limb muscles. J Anat. 1973 Oct;116(Pt 1):1–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woledge R. C. The energetics of tortoise muscle. J Physiol. 1968 Aug;197(3):685–707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laarse W. J., Diegenbach P. C., Hemminga M. A. Calcium-stimulated myofibrillar ATPase activity correlates with shortening velocity of muscle fibres in Xenopus laevis. Histochem J. 1986 Sep;18(9):487–496. doi: 10.1007/BF01675616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]