Abstract

Background

Mental health stigma in the workplace has been widely recognized, and workplace programs have been created to improve self-awareness and resiliency, while decreasing stigma. Prior meta-analyses of The Working Mind (TWM) program suggest positive benefits. The current meta-analysis was based on the shift to online delivery of TWM during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was predicted that program outcomes would be approximately the same as in prior analyses of in person delivery of the TWM program.

Method

TWM program was delivered by expert trainers to a total of 1,159 participants across six workplace settings. Participants provided informed consent and survey data, prior to, just after and 3 months after the program. Outcomes included stigma, resiliency and readiness for change. Standardized assessments were employed, consistent with prior program analyses.

Results

Significant reductions in stigma and increases in self-reported resiliency occurred, with immediate overall effect sizes of 0.33 and 0.40, respectively. Some variability among workplace settings was observed. Males had a somewhat better result than females and people who reported worse mental health at program initiation had somewhat better results than others, but these were modest effects. The results were largely stable until the 3-month follow-up assessment period. Attrition across the study interval was considerable.

Conclusions

The virtual delivery of TWM yielded meta-analytic results that were comparable to previous in person outcomes, both in terms of immediate and 3-month assessment intervals. Some variability in outcomes was noted, and some return towards baseline was observed at the 3-month follow-up period. The issue of attrition was also noted, possibility due to effects of online fatigue and the voluntary nature of the study. Suggestions for further study of program effects are given, and workplace wellness programs are encouraged.

Plain Language Summary Title

Outcomes of a virtual program to address mental Health Stigma in the workplace:

Keywords: (public) stigma, mental health, evaluation, meta-analysis, virtual

Plain Language Summary

Stigma related to mental health in the workplace can lead to worker limitations and reduced organizational effectiveness and success. The current study examined the outcomes of a remotely delivered workplace program that addresses workplace stigma, both in terms of stigma reduction and self– reported improvements in participant resiliency. Across a series of six settings, outcomes were on average positive, with results similar to previous studies that examined the same program in a live delivery format. These results suggest that The Working Mind program can be expected to deliver positive results across diverse settings, and in both live and virtual formats, The article includes discussion of both strengths and limitations of the current work, and directions for further program development and study.

Résumé

Contexte:

La stigmatisation de la santé mentale en milieu de travail est largement reconnue, et des programmes sur le lieu de travail ont été créés afin d’augmenter la prise de conscience et la résilience tout en réduisant la stigmatisation. Des méta-analyses antérieures du programme L’esprit au travail (EAT) suggèrent des effets bénéfiques. La présente méta-analyse était basée sur le passage à l’administration en ligne du programme EAT durant la pandémie de COVID-19. Il était anticipé que les résultats du programme seraient comparables à ceux des analyses antérieures de l’administration du programme en présentiel.

Méthodologie:

Le programme EAT a été administré par des animateurs certifiés à un total de 1159 participants sur six lieux de travail. Les participants ont fourni leur consentement éclairé et les données d’enquête avant, immédiatement après et trois mois après le programme. Les paramètres étudiés étaient la stigmatisation, la résilience et la volonté de changer. Des évaluations uniformisées ont été utilisées, comme pour les analyses précédentes du programme.

Résultats:

Des réductions significatives de la stigmatisation et des augmentations de la résilience ont été obternues, selon les auto-évaluations, avec une taille d’effet global immédiat de 0,33 et 0,40 respectivement. Une certaine variabilité entre les lieux de travail a été observée. Les résultats chez les hommes étaient quelque peu supérieurs à ceux des femmes, et les personnes qui avaient signalé la pire santé mentale au début du programme ont eu des résultats légèrement meilleurs que les autres, mais ces effets étaient modestes. Les résultats sont restés en grande partie stables jusqu’à l’évaluation de suivi à trois mois. L’attrition tout au long de l’étude a été considérable.

Conclusions:

L’administration virtuelle du programme EAT a donné des résultats méta-analytiques semblables à ceux des analyses antérieures en présentiel, à la fois dans l’immédiat et au bout de trois mois. Une certaine variabilité des résultats a été constatée et un certain retour aux valeurs initiales a été observé au terme du suivi à trois mois. Un problème d’attrition a également été noté, probablement un effet de la fatigue en ligne et de la nature volontaire de l’étude. Des suggestions pour une analyse plus approfondie des effets du programme sont offertes et la mise en place de programmes de bien-être en milieu de travail est encouragée.

Introduction

Mental health problems are associated with a range of workplace concerns, including increased absenteeism from work and use of extended time for medical leaves, reduced presenteeism in the workplace, higher staff turnover, and increased recruitment and training costs.1–4 Further risks include possible stigmatization of employees with mental health challenges and difficulties in their recognition and promotion. 5 Workers with mental health problems may even stigmatize themselves, in the forms of self isolation, avoidance, and not stepping forward for appropriate advancements or recognition.6,7 It has been suggested that workplace mental health programs can address some of the above concerns and while they have direct costs, they also have considerable benefits and are highly cost effective. 8

The Opening Minds program of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) has targeted workplace stigma as one of four areas for attention. 9 Building from work of the Department of National Defence and its Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) program, adaptations were made for first responder groups and to include an explicit focus on workplace stigma. 10 Later adaptations to the general workplace led to the program being re-named The Working Mind (TWM). TWM has been delivered to more than 400,000 Canadians in a wide range of workplace settings.

TWM is based on a logic model and information about best practices in stigma reduction.1,9 The program utilizes a continuum model to discuss how individuals can vary in terms of their mental health status. The continuum ranges from green (positive mental health) to yellow, orange and red (potentially indicative of a mental disorder). The program discusses four broadly applicable coping skills, highlights different forms of stigma,11,12 and discusses anti-stigma strategies. The program includes didactic information, discussion, case studies, and videos of people with lived experience of stigma in the workplace. Based on the idea that contact-based education with others who have lived experience of mental health problems, video segments are used in program delivery. A half-day version of TWM exists for all workers, and an extended 6-hour version discusses legal and ethical responsibilities of workplace leaders related to mental health concerns. TWM is a manualized program which can be delivered by external trained and certified facilitators or trained employees. Although the latter “Train the Trainer” model is recommended to promote program maintenance, training is intensive and not everyone who attends training is certified for program delivery.

Organizations are invited to engage in evaluation, which involves a set of survey instruments prior to program delivery, just after, and at a 3-month follow-up. For live delivery of the program, the initial and post-surveys are administered using paper and pencil methods when the program is delivered, and these surveys are then transferred to a computer file. The 3-month follow-up assessment is administered using a secure web-based survey system. Informed consent is obtained in all instances, and completion of surveys is not a requirement for program attendance. The two primary program outcomes of TWM are workplace stigma, which is expected to reduce after program delivery, and personal resilience, which is expected to increase. Additional items often inquire about workplace culture and follow-up questions ask about program improvement.

Open trials of TWM have resulted in two previous multi-site meta-analyses, both for first responders 13 and a broader set of workplace settings. 11 The pre–post effect sizes have varied somewhat group to group, but range between 0.26 and 0.38 for stigma reduction, and 0.32 and 0.50 for resiliency increase. One cluster randomized trial of TWM 14 entailed either program delivery without delay, or with a 3-month delay, within a provincial health care system. That study revealed significant decreases in stigma and increases and resilience after program delivery, but that in the delayed intervention arm no changes occurred until the program was delivered. Overall effect sizes across the two arms of the study were 0.46 and 0.57 for stigma reduction and increased resilience, respectively.

A recent challenge for mental health programs has been the need for physical distancing associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. At the outset of the pandemic, staff within the Opening Minds program created a virtual delivery format for TWM, but with the same didactic content and other processes as in the live delivery format. The major modifications with virtual delivery include a reduced likelihood of using the Train the Trainer approach, limited interaction among program participants, and the need to only use online program evaluation surveys. To conduct the surveys, administrators provide a confidential list of names and email addresses for participants to the research team, and participants are invited to use a secure survey system.

The current report is based on the virtual delivery of TWM program at six organizations across Canada, in the period of 2019 to 2023. These organizations include provincial energy and health care organizations, and Canadian branches of international businesses involved in travel, energy, and shipping. All evaluations included an agreement between the organization and the Opening Minds program, to license, deliver the program and conduct program evaluation. The prediction was that the effect sizes for both stigma reduction and increase in self-reported resiliency would approximate those from previous meta-analyses. Participant gender and baseline mental health were also explored as potential moderators of outcomes, and while no formal hypotheses were made, it was thought that these analyses might suggest directions for program development or deployment.

Methods

Study Design

All of the replications in this study entailed the open delivery of TWM, with measurement immediately before and after program delivery, and 3 months later.

Participants

Eligible participants included anyone at any of the participating organizations who had not previously taken TWM. The scheduling of organizations was largely random, based on organizational adoption and the scheduling of facilitators by the Opening Minds program staff.

Procedure

Participants were sent an email approximately 4 days prior to the program, with the request to read and provide consent and complete the initial evaluation before they undertook the training. Consenting participants were sent another survey immediately after the program and provided an interval of up to 4 days to complete the assessment, as well as the follow-up evaluation materials 3 months after the program with a similar period to complete the assessment. Following the final assessment cases with consent were matched across time and the data set was de-identified.

Primary Outcomes

Two primary outcomes were the reduction of workplace stigma and improvement in resiliency skills.

Workplace stigma was measured with the Opening Minds Scale for Workplace Attitudes (OMS-WA15–17), which is a 22-item 5-point Likert type self-report scale. The OMS-WA assesses five dimensions. The four negatively keyed subscales are social distance/avoidance, dangerousness or unpredictability, work-related beliefs/competency, and responsibility for illness. Example items include “You can’t rely on an employee with a mental illness”, and “Most employees with a mental illness are too disabled to work.” The remaining helping behaviors scale measures the desire to support other employees with mental health challenges. To obtain a total score, the helping behaviors scale is reverse coded, and an average of all items is computed. The OMS-WA has been examined psychometrically across a variety of data sets. 18 The five-factor structure has been supported16,19 and the scale has been shown to be sensitive to change.11,13,14 The OMS-WA has been used consistently as a primary outcome measure in workplace stigma reduction programs of the MHCC. 16

Resiliency

The 5-item self-report Brief Resiliency Scale was used, as in previous TWM program analyses.11,13,14 Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of self-reported resiliency and ability to recover after difficult or traumatic events. Items include “I have the skills to cope with traumatic events or adverse situations,” and “I believe I can recover quickly if I am negatively affected by traumatic events or adverse situations.” This scale demonstrated high internal reliability and sensitivity to change in previous meta-analyses of TWM.11,13

Ancillary Outcomes

Most TWM evaluations include varied measures based on organizational interests. One frequently used set of items evaluates the participants’ sense of ability to manage mental health concerns in the workplace. These “readiness items” are not part of a validated scale but reflect common sense statements such as “I understand how mental health problems present in the workplace.” and “When I am concerned, I ask my colleagues how they are doing” (see Table 1 for all items). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert type scale, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of endorsement. These items were analyzed individually, as a secondary perspective on program outcomes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Internal Consistency (Cronbach's α/McDonald's Ω) of Measures for Complete Sample (N = 1159).

| Pre | Post | Follow-up | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal consistency | Internal consistency | Internal consistency | |||||||||||

| Measures (Range = 1–5) | # items | N | M (SD) | Α | Ω | N | M (SD) | α | Ω | N | M (SD) | α | Ω |

| Total OMS-WA scale | 22 | 1012 | 1.80 (0.50) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 501 | 1.64 (0.49) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 254 | 1.66 (0.47) | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Social distance/avoidance | 5 | 1012 | 1.60 (0.62) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 501 | 1.44 (0.57) | 0.86 | 0.86 | 253 | 1.48 (0.55) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Dangerousness/unpredictably | 5 | 1012 | 1.94 (0.63) | 0.75 | 0.76 | 501 | 1.72 (0.62) | 0.79 | 0.79 | 254 | 1.74 (0.62) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Work-related beliefs/competency | 5 | 1011 | 1.83 (0.63) | 0.80 | 0.81 | 501 | 1.63 (0.62) | 0.85 | 0.85 | 254 | 1.62 (0.59) | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Helping behavior (R) | 4 | 1012 | 2.03 (0.69) | 0.67 | 0.67 | 501 | 1.97 (0.72) | 0.69 | 0.67 | 254 | 2.03 (0.72) | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| Responsibility for illness | 3 | 1010 | 1.51 (0.62) | 0.76 | 0.77 | 501 | 1.39 (0.56) | 0.80 | 0.81 | 253 | 1.41 (0.54) | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Resiliency skill scale | 5 | 997 | 3.35 (0.72) | 0.85 | 0.84 | 491 | 3.56 (0.67) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 242 | 3.58 (0.67) | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| Readiness Statements: | |||||||||||||

| “I understand how mental health problems present in the workplace.” | 1 | 995 | 3.30 (0.89) | — | — | 400 | 3.93 (0.68) | — | — | 244 | 3.78 (0.68) | — | — |

| “I plan to seek help for my mental health problems.” | 1 | 993 | 3.69 (0.84) | — | — | 400 | 4.09 (0.72) | — | — | 238 | 3.99 (0.71) | — | — |

| “When I am concerned, I ask my colleagues how they are doing.” | 1 | 994 | 4.07 (0.74) | — | — | 400 | 4.28 (0.59) | — | — | 236 | 4.18 (0.57) | — | — |

| “I talk about mental health issues as freely as physical health issues.” | 1 | 994 | 3.33 (1.09) | — | — | 400 | 3.57 (1.04) | — | — | 241 | 3.57 (1.03) | — | — |

| “I understand management practices that promote the performance and well-being of all employees.” | 1 | 993 | 3.52 (0.92) | — | — | 400 | 4.11 (0.69) | — | — | 240 | 3.95 (0.75) | — | — |

Notes: The OMS-WA Helping behavior subscale has been reverse coded to align with other subscales.

For internal consistency analyses, Ns = 992–1011 (pre); Ns = 490–501 (post); Ns = 249–253 (follow-up). α = Cronbach's Alpha. Ω = McDonald's Omega.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive analyses were completed using SPSS Version 29. A pooled data analysis using STATA Version 12 and the ‘metan’ command 20 was used for the meta-analyses, with study level analyses of moderators. This analysis provides forest plots, as well Q statistics and I2 to assess the homogeneity of the results across sites. A random intercept linear mixed model was used to analyze the pre–post differences (Δ = pre–post) for participants who provided matched data (n = 394) on the program outcomes with workplace site modeled as a random effect. Both the total and subscale scores for the OMS-WA were analyzed. This modeling enabled additional variables (i.e., gender, self-rated mental health at baseline) to be entered as independent variables. Changes from the post to the follow-up assessment for the OMS-WA, resiliency skills measure, and the readiness to engage questions were also analyzed using a random intercept linear mixed model, with the subsample that provided follow-up responses (n = 159). While significant changes were expected to occur in the pre- to post-time period, differences were not expected in the follow-up period.

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were advised that the data were being collected as part of program evaluation but that their participation was voluntary and did not affect their ability to attend the program. The consent information advised them that the data were held separately in a secure computer system under the control of the first author, that ethics approval had been granted by the organization and they had the right to raise any concerns about the project with the ethics board.

Results

Data from a total of 1,159 participants were collected. The average age was 44.06 years (SD = 9.30, range = 16–52), and gender was self-identified as 62.0% male, 36.8% female, and 1.2% gender diverse. Table 1 presents the primary outcome values for the entire sample, including 1,013 pre-surveys, 502 post-surveys, and 254 3-month follow-up surveys. Of these, there are 394 pre–post matches, of which 159 also had follow-up matches. The loss to follow-up in this study raises the possibility of differential attrition on key variables. To examine this possibility, the baseline scores of those who only completed the pre-survey (n = 575), those who completed the pre- and post-surveys, but not the follow-up (n = 235), and those who completed the follow-up (n = 203) were compared using one-way ANOVAs and a nominal 0.05 level of significance. No significant differences emerged between these groups regarding baseline stigma, resiliency, and four of the five readiness to engage questions. The fifth readiness question did yield a significant difference (p = 0.023), however, participants who completed the follow-up had the lowest baseline scores on this question, suggesting they were the ones that may have benefited most from attending.

Table 1 includes Cronbach's alpha 21 and McDonald's omega 22 internal reliability coefficients for the outcome measures. As coefficients of .7 to .8 are considered acceptable, 22 the reliability coefficients for the current study are at least acceptable, with the exception of the Helping Behavior subscale of the OMS-WA. This 4-item subscale had reliabilities that ranged from 0.62 to 0.69 across the three assessment intervals. Results from this subscale should be understood in the context of this issue.

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses for the three outcomes of the study, using the pre and post scores, and site as a variable in the prediction model. All of the tests for the change between pre and post were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.001), except the helping behaviors’ subscale of the OMS-WA (p = 0.31). All differences were also in the predicted direction, as stigma was reduced, and both resiliency and readiness increased. The analysis of site effects was not significant for either the total OMS-WA, heterogeneity χ2(5) = 7.13, p = 0.21, nor the Brief Resiliency Scale, heterogeneity χ2(5) = 2.29, p = 0.81.

Table 2.

Random Intercept Mixed Model Regression: OMS-WA (and Subscales), Resiliency Skills, and Readiness Statements, Pre- to Post-Workshop Change (Δ = Pre–Post).

| M (SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | Pre | Post | Coef. | SE | 95% CI | Z | p |

| Total OMS-WA Scale | 392 | 1.75 (0.47) | 1.61 (0.47) | 0.1515 | 0.0342 | [0.0845, 0.2186] | 4.43 | <0.001 |

| Social Distance/Avoidance | 392 | 1.56 (0.57) | 1.42 (0.53) | 0.1387 | 0.0387 | [0.0628, 0.2145] | 3.58 | <0.001 |

| Dangerousness/Unpredictably | 392 | 1.90 (0.61) | 1.68 (0.59) | 0.2435 | 0.0470 | [0.1514, 0.3356] | 5.18 | <0.001 |

| Work-related beliefs/Competency | 392 | 1.77 (0.61) | 1.59 (0.59) | 0.1809 | 0.0296 | [0.1229, 0.2388] | 6.12 | <0.001 |

| Helping Behavior | 392 | 2.01 (0.67) | 1.96 (0.70) | 0.0697 | 0.0682 | [−0.0640, 0.2034] | 1.02 | 0.307 |

| Responsibility for Illness | 392 | 1.44 (0.57) | 1.36 (0.53) | 0.0752 | 0.0237 | [0.0288, 0.1216] | 3.18 | 0.001 |

| Resiliency Skills | 388 | 3.30 (0.72) | 3.57 (0.67) | −0.2767 | 0.0359 | [−0.3470, −0.2063] | −7.71 | <0.001 |

| Readiness Statements: | ||||||||

| “I understand how mental health problems present in the workplace.” | 320 | 3.20 (0.91) | 3.94 (0.65) | −0.7116 | 0.1330 | [−0.9723, −0.4509] | −5.35 | <0.001 |

| “I plan to seek help for my mental health problems.” | 320 | 3.65 (0.85) | 4.09 (0.69) | −0.4382 | 0.0512 | [−0.5386, −0.3378] | −8.55 | <0.001 |

| “When I am concerned, I ask my colleagues how they are doing.” | 319 | 4.06 (0.75) | 4.25 (0.59) | −0.1990 | 0.0661 | [−0.3286, −0.0693] | −3.01 | 0.003 |

| “I talk about mental health issues as freely as physical health issues.” | 320 | 3.34 (1.13) | 3.58 (1.02) | −0.2336 | 0.0758 | [−0.3822, −0.0850] | −3.08 | 0.002 |

| “I understand management practices that promote the performance and well-being of all employees.” | 320 | 3.50 (0.94) | 4.10 (0.674) | −0.5974 | 0.0704 | [−0.7353, −0.4594] | −8.29 | <0.001 |

Note: Site 2 did not collect readiness statements at time 2, so there were only 5 sites included in those analyses. Site sample sizes ranged from n = 22 to n = 102.

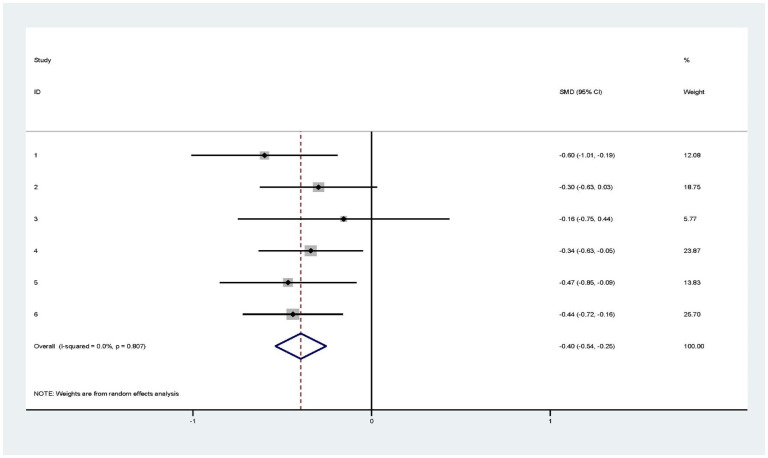

Figures 1 and 2 present the forest plots for the meta-analysis for the total OMS-WA scale, and the resiliency scale, respectively. Although one site evidenced minimal stigma reduction, the average effect size was 0.33, and two sites either reached or were close to an effect size of 0.60. Resiliency scores also revealed a pattern of overall change, with the possible exception of one site. The average effect size for resiliency was 0.40, with one site attaining an effect size of .60.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of TWM program effects on stigma (OMS-WA; pre–post) by site. Note: CI = confidence interval. SMD = standard mean difference.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of TWM program effects on resiliency skills (pre–post) by site. Note: CI = confidence interval. SMD = standard mean difference.

Gender (female coded 0 [constant], male coded 1) and baseline mental health (intercept = 1 on the scale) were examined as predictors of change. Although both genders evidenced decreases in stigma, males exhibited a marginally greater reduction in stigma than females, p = 0.042, female (constant): Coeff. = 0.1160 (SE = 0.0387), 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.0402, 0.1918], z = 3.00, p = 0.003, and male status, male: Coeff. = 0.0630 (SE = 0.0309), 95%CI = [0.0024, 0.1236], z = 2.04, p = 0.042. Participants with lower self-reported overall mental health before the program evidenced more change in stigma than participants with higher initial mental health, Constant/Intercept (1 on scale): Coeff. = −0.0344 (SE = 0.0160), 95% CI = [−0.0657, −0.0031], z = −2.15, p = 0.031, Slope: Coeff. = 0.2466 (SE = 0.0548), 95% CI = [0.1392, 0.3540], z = 4.50, p < 0.001, p = 0.023. In contrast, neither gender (p = 0.392) nor baseline mental health (p = 0.915) emerged as a significant predictor of change for the self-reported resiliency score.

In contrast to the expectation of stable results, the 3-month OMS-WA score was significantly higher than at post-test, p = 0.038 (see Table 3). None of the OMS-WA subscales revealed a significant change between the post-test and follow-up periods, however, and for matched scores the 3-month follow-up average was still significantly lower than for the pre-test evaluation, suggesting that the program continued to have positive results. The resiliency scale also showed no significant difference between the post-test and follow-up assessment periods. Finally, while one of the readiness statements suggested a reduced score more in line with the original score; “I understand how mental health problems present in the workplace.” (p = 0.013), another suggested even more positive results at the follow-up assessment; “I talk about mental health issues as freely as physical health issues.” (p = 0.050).

Table 3.

Random Intercept Mixed Model Regression: Post to Follow-Up Change for Adapted OMS-WA, Resiliency Skills, and Readiness Statements (Δ = Post–Follow-Up).

| M(SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | Post | Follow-up | Coeff. | SE | 95% CI | z | p |

| Total OMS-WA Scale | 159 | 1.59 (0.46) | 1.64 (0.47) | −0.0554 | 0.0268 | [−0.1080, −0.0003] | −2.07 | 0.038 |

| Social Distance/Avoidance | 159 | 1.42 (0.54) | 1.49 (0.57) | −0.0695 | 0.0362 | [−0.1405, 0.0002] | −1.92 | 0.055 |

| Dangerousness/Unpredictably | 159 | 1.64 (0.59) | 1.71 (0.62) | −0.0758 | 0.0420 | [−0.1581, 0.0006] | −1.81 | 0.071 |

| Work-related beliefs/Competency | 159 | 1.57 (0.57) | 1.60 (0.57) | −0.0327 | 0.0388 | [−0.1088, 0.0434] | −0.84 | 0.399 |

| Helping Behavior | 159 | 1.93 (0.62) | 2.00 (0.66) | −0.0660 | 0.0524 | [−0.1688, 0.0367] | −1.26 | 0.208 |

| Responsibility for Illness | 159 | 1.35 (0.51) | 1.38 (0.52) | −0.0294 | 0.0341 | [−0.0961, 0.0374] | −0.86 | 0.389 |

| Resiliency Skills | 151 | 3.58 (0.63) | 3.59 (0.68) | −0.0119 | 0.0456 | [−0.1013, 0.0775] | −0.26 | 0.794 |

| Readiness Statements: | ||||||||

| “I understand how mental health problems present in the workplace.” | 137 | 4.00 (0.58) | 3.86 (0.62) | 0.1387 | 0.0558 | [0.0294, 0.2480] | 2.49 | 0.013 |

| “I plan to seek help for my mental health problems.” | 133 | 4.09 (0.65) | 4.03 (0.71) | 0.0602 | 0.0590 | [−0.0554, 0.1757] | 1.02 | 0.308 |

| “When I am concerned, I ask my colleagues how they are doing.” | 129 | 4.21 (0.55) | 4.22 (0.54) | −0.0078 | 0.0459 | [−0.0976, 0.0821] | −.17 | 0.866 |

| “I talk about mental health issues as freely as physical health issues.” | 133 | 3.55 (1.03) | 3.69 (1.00) | −0.1429 | 0.0730 | [−0.2860, 0.0002] | −1.96 | 0.050 |

| “I understand management practices that promote the performance and well-being of all employees.” | 133 | 4.09 (.60) | 4.07 (.62) | −0.0226 | 0.0481 | [−0.0717, 0.1168] | 0.47 | 0.639 |

Note. Workplace site sample sizes ranges from n = 8 to n = 53.

Discussion

TWM program was developed as a program to promote workplace mental health by the Mental Health Commission of Canada. 10 Analyses at individual sites 14 and meta-analyses across a variety of sites11,13 have shown that TWM yields significant reductions in workplace stigma, as well as improvements in self-reported resiliency. In general, these positive program results persist over time and are not affected by the particularities of different workplace settings.

Although TWM program was originally developed for face-to-face delivery, the pandemic compelled a shift to online program delivery with the same content. Virtual delivery enables the inclusion of people from diverse settings, as well as a broader set of program facilitators, as they may be geographically distant from the program participants. The current results provide important data about TWM as a program when delivered in virtual format, but also as another indicator of the potential value of virtual programs in general.23,24

The overall effect sizes from the current meta-analyses were 0.33 for stigma reduction and 0.40 for increases in self-reported resiliency. These results were statistically significant, and generally maintained at the follow-up assessment. TWM can be delivered in virtual format with the expectation that outcomes will approximate those of in-person delivery. It should be noted, however, that one setting failed to show reductions in stigma and another setting had only a modest change in resiliency, so further study of the program, and outcome predictors are warranted. Further, the OMS-WA revealed a significant increase in stigma scores from the post-test to follow-up period, even though the follow-up scores were still significantly lower than the baseline scores and no specific subscale of the OMS-WA showed a significant change from post-test to follow-up. As has been previously suggested,10,15 it may be unreasonable to expect that a brief program should have long-term benefit. The use of “booster sessions” and reminders or refreshment courses are likely needed to maintain and perhaps strengthen program benefits.

The current study benefitted from several strengths. The measurement was consistent with prior outcome studies of TWM, as was the design of the program evaluation. The program was manualized, and the program facilitators were all trained to deliver the program. The study was conducted with ethical approval and a number of safeguards ensured informed consent and protection of privacy.

There are several study considerations. Organizations typically adopt the TWM program and simply want it delivered. As such, randomized trials of TWM are limited to a single study. 14 It is also the case that while the evaluation included standardized outcome measures and a set of ancillary questions, other outcomes of the program are possible. Future studies of TWM should consider an extended set of outcomes. Secondly, the follow-up assessment was limited to a single 3-month interval. It is possible that program results would differ with a longer follow-up interval. Third, while the program was manualized, there was no direct examination of program fidelity. The largest study limitation was attrition. While there was a sufficient sample size to estimate effect sizes and the no variable showed differential attrition that might delimit study conclusions, other variables could be implicated. The attrition in the current study was considerably more than in previous meta-analysis of in person program delivery.11,13

Future Directions

The evidence is that TWM delivered in distant fashion has roughly equivalent outcomes to live delivery, across diverse employment settings, and for participants with different characteristics. This outcome is not too surprising, as program elements such as the contact-based videos and discussion cases are tailored to diverse workplaces. This said, further study could be made using randomized comparisons of live versus distant delivery of the program, as other studies suggest that live delivery of anti-stigma programs have better outcomes. 25 Further study with different settings may also identify predictors of program outcomes. The current report demonstrated marginally significant better results for males than females, and for people with somewhat worse mental health prior to the program than other participants prior to the program, implicating the need for further study of program predictors. Finally, because the TWM program is conducted in groups, it is possible that there may be unique differences among groups who receive the program, and this issue could be the subject of further inquiry.

One of the issues raised in prior meta-analyses of TWM was that of the longevity of program effects.11,14 It would be of benefit to study the longer-term results of TWM, and to investigate booster sessions or refresher content to see if program effects can be maintained or bolstered with further exposure to program elements. Overall, future studies should consider a broader range of outcomes, over a longer period of time, and with some incentive to reduce attrition.

It is often difficult to modify a program that is developed and disseminated. The logic model for TWM brings several of the known elements of stigma reduction into effect, 26 including psychoeducation, contact-based education, cases and discussion. An instructive exercise would be to discern how much benefit is associated with program components. Such a component analysis could potentially streamline the program, and demonstrate how the program elements work together, thus informing similar programs in the field.

There have been recent increases in the development and deployment of mental health programs in the workplace, and it is important to bear in mind that TWM is only one of a growing set of such programs and practices.1–3 Although TWM is based on a conceptual model, 9 best practices in the field of stigma reduction, 10 and a body of evidence,12,13,15 unique programs ought not ever be expected to meet all training and mental health needs in the employment sphere. Optimal health involves promotion, assessment, maintenance, early intervention, and postvention 27 to address the continuum of care. Also, group-based programs such as TWM are best suited to address issues related to self and social stigma. Other workplace programs are needed to address the range of stigma concerns that may be identified, including structural stigma. Finally, it is important to note that programs such as TWM are only one component of the overall health system which involves individuals, the workplace, communities and the formal healthcare system.

Acknowledgements

Funds for this study were provided in part by the Opening Minds program of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, through grant UCP01-60-13690-10015106 at University of Calgary.

Keith Dobson and Andrew Szeto have contracted work with the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Mental Health Commission of Canada (grant number UCP01-60-13690-10015106 University of Calgary).

ORCID iDs: Keith S. Dobson https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9542-0822

Brittany Lindsay https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9315-4986

References

- 1.Wu AMHS, Roemer EC, Kent KB, Ballard DW, Goetzel RZ. Organizational best practices supporting mental health in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(12):e925-e931. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goetzel RZ, Roemer EC, Holingue C, et al. Mental health in the workplace: a call to action proceedings from the mental health in the workplace—public health summit. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(4):322-330. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner SL, Koehn C, White MI, et al. Mental health interventions in the workplace and work outcomes: a best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2016;7(1):1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim KL, Jacobs P, Ohinmaa A, Schopflocher D, Dewa CS. A new population-based measure of the economic burden of mental illness in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2008;28(3):92-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelloway EK, Dimoff JK, Gilbert S. Mental health in the workplace. Ann Rev Org Psych Org Beh. 2023;10:363-387. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-050527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaMontagne AD, Martin A, Page KM, et al. Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:131. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steger M, de Dik BJ. Work as meaning: individual and organizational benefits of engaging in meaningful work. In: Garcea N, Harrington S, Linley PA. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology and work. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010, 131-142. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deloitte Insights (2019). The ROI in workplace mental health programs: Good for people, good for business. Available from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ca/Documents/about-deloitte/ca-en-about-blueprint-for-workplace-mental-health-final-aoda.pdf

- 9.Dobson KS, Stuart H, editors. The stigma of mental illness: models and methods of stigma reduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021, 131-142. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szeto A, Dobson KS, Luong D, Krupa T, Kirsh B. Workplace antistigma programs at the Mental Health Commission of Canada: Part 2. Lessons learned. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(6S):S13-S17. doi: 10.1177/0706743719842563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobson KS, Stuart H. Prejudice and discrimination related to mental illness. In: Dobson KS, Stuart H, editor. The stigma of mental illness: models and methods of stigma reduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobson KS, Szeto A, Knaak S. The Working Mind: a meta-analysis of a workplace mental health and stigma reduction program. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(1_suppl):39S-47S. doi: 10.1177/0706743719842559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szeto A, Dobson KS, Knaak S. The road to mental readiness for first responders: a meta-analysis of program outcomes. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(1_suppl):18S-29S. doi: 10.1177/0706743719842562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA. Mental illness stigma: types, constructs, and vehicles for change. In Corrigan PW, editor, The stigma of disease and disability: understanding causes and overcoming injustices. American Psychological Association, 2014, p. 35-56. 10.1037/14297-003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobson KS, Markova V, Wen A, Smith LM. Effects of the anti-stigma workplace intervention “working mind” in a Canadian health-care setting: a cluster-randomized trial of immediate versus delayed implementation. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(5):495-502. doi: 10.1177/0706743720961738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szeto ACH, Luong D, Dobson KS. Does labeling matter? An examination of attitudes and perceptions of labels for mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidem. 2016;48(4):659-671. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0532-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobson KS, Szeto ACH. The assessment of mental health stigma in the workplace. In Dobson KS, Stuart H. editors. The stigma of mental illness. Oxford University Press, 2021, p. 55-70. doi: 10.1093/med/9780197572597.003.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehme BAE, Shields RE, Asmundson GJG, Szeto ACH, Dobson KS, Carleton RN. A short version of the opening minds scale workplace attitudes: factor structure and factorial validity in a sample of Canadian public safety personnel. Can J Behav Sci. 2023;56(2):157-162. 10.1037/cbs0000350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindsay BL, Dobson KS, Krupa T, Knaak S, Szeto ACH. A psychometric evaluation of the Opening Minds Scale for Workplace Attitudes (OMS-WA): a measure of public stigma towards mental illnesses in the workplace. Discov Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RJ, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ, Harbord RM, Stern JAC. Metan: fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J. 2008;8(1):3-28. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0800800102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 1951;16(3):297-334. doi: 10.1007/bf02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osburn HG. Coefficient alpha and related internal consistency reliability coefficients. Psych Methods. 2010;5(3):343-355. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.5.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenwood H, Krzyzaniak N, Peiris R, et al. Telehealth versus face-to-face psychotherapy for less common mental health conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Ment Health. 2022;9(3):e31780. doi:10.2196/31780. Published 2022 Mar 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byambasuren O, Greenwood H, Bakhit M, et al. Comparison of telephone and video telehealth consultations: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2023; 25: e49942. doi:10.2196/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):963-973. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thornicroft G, Sunkel C, Alikhon Aliev A, et al. The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. Lancet. 2022;400(10361):1438-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ. Institute of Medicine (IOM)-reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]