Abstract

Background and Objective: As the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) continues to rise, physicians will be challenged to manage increasing numbers of patients with moderate to severe AD. Despite the need for active treatment and management, the growing AD population has been overlooked in the primary care setting. Currently, the approved treatments for AD are the cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, riva-stigmine, and galantamine and the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine. The objective of this article is to review recent pharmacologic studies and discuss implications for treatment of moderate to severe AD.

Data Sources and Study Selection: A PubMed search was performed for publications from 1995 to 2004 using the search terms moderate or severe, efficacy, and Alzheimer. The search was limited to randomized, controlled trials published in English. The search was further restricted to prospective studies of pharmacologic agents that included patients with severe dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination score < 10). A total of 96 citations were retrieved. Of these, 5 met the inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Synthesis: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients with moderate to severe AD have been conducted for donepezil and memantine. Patients treated with donepezil monotherapy showed improved cognition, stabilized function, and improved behavioral symptoms. Patients treated with memantine monotherapy showed less than expected decline in cognition, function, and behavioral symptoms. Patients who received memantine treatment adjunctive to stable, long-term donepezil treatment derived cognitive, functional, and behavioral benefits from add-on therapy.

Conclusion: Overall, published studies of donepezil and memantine report treatment benefits.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with advanced age. Currently, total annual costs of AD exceed $100 billion,1 making AD the third most expensive disease in the United States, preceded only by heart disease and cancer.2 The prevalence of AD doubles approximately every 5 years after the age of 65,3 approaching 50% in persons over the age of 85.4 As the baby boomer generation is reaching retirement age, AD will affect more people than ever before. By the year 2025, an estimated 18% of the U.S. population will be over age 65.5 Therefore, the aging of the population will have a profound medical and social impact.

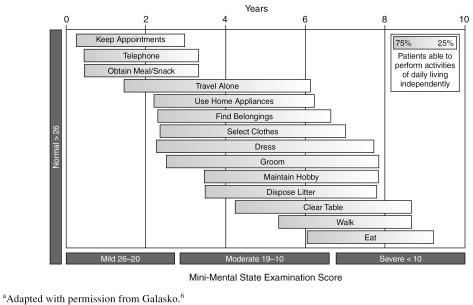

AD is characterized by the gradual onset and progressive worsening of cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms (Figure 1).6 In the mild stage of the disease (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 20–26), symptoms can be subtle and include short-term memory loss, impaired ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as driving or managing finances, and behavioral changes such as depression.6 In the moderate stage of AD (MMSE score of 10–19), cognitive decline is more pronounced, affecting language and abstract thought. IADLs are almost completely lost, and behavioral and mood symptoms increase in number and severity.6 In the severe stage (MMSE score < 10), patients lose the ability to use complex language and perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs), such as feeding and dressing oneself, with overall decline such that patients become totally dependent.6 Agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, apathy, irritability, and aberrant motor function are the most prevalent behavioral symptoms in this stage.7

Figure 1.

Stages of Alzheimer's Disease Symptoms as Defined by the Mini-Mental State Examinationa

In more advanced AD, symptoms have profound medical and social consequences. Cognitive deficits prevent patients from comprehending written material or television and from engaging in meaningful conversation. Functional deficits prevent these patients from getting needed exercise and from participating in social activities. Physical outlets are important for preventing other medical conditions such as pneumonia, pressure sores, and urinary tract infections. Behavioral symptoms in patients with more advanced AD often result from discomfort because these patients are unable to report conditions such as pain, hunger, or cold. Behaviors resulting from discomfort can be complicated by the frustration of functional impairment, mood disorders, and delusions and hallucinations.8

As the elderly population grows, more patients with AD will be managed in the primary care setting. Providing optimal care for patients with severe AD represents a major health care challenge. In many cases, primary care physicians will need to provide care for the entire course of the disease. Complications such as decubitus ulcers, aspiration pneumonia, and malnutrition may arise in the severe stage of AD.8 Diagnosis and treatment of comorbid illnesses are critical for the success of treatment plans.9 Primary care physicians will also need to monitor care-giver burden, which increases significantly with disease progression and often makes nursing home placement necessary.10 The additional demands of caring for patients with advanced dementia drive up the costs of treatment, which increase approximately 2-fold as the disease progresses from the mild to severe stage.11

The following discussion summarizes the data from recent prospective pharmacologic studies in patients with moderate to severe AD. Of the pharmacologic treatments, cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) are approved for use in patients with mild to moderate AD,12–20 while memantine is an approved treatment for patients with moderate to severe AD.21 Studies of donepezil also suggest that ChEIs have efficacy in AD beyond the mild to moderate stage.19,22

DATA SOURCES AND STUDY SELECTION

A PubMed search was performed for publications from 1995 to 2004 using the search terms moderate or severe, efficacy, and Alzheimer. The search was limited to randomized, controlled trials published in English. A total of 96 references were retrieved. Of these, 519,21–24 met the additional criterion of being prospective pharmacologic studies including patients with severe dementia (MMSE score < 10).

DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS

This literature search returned a relatively small number of studies investigating the efficacy of donepezil and memantine for moderate to severe AD. Although rivastigmine and galantamine are approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of their efficacy in more advanced disease have yet to be published.

Primary outcome measures used in some of the studies included the following instruments. Severe Impairment Battery (SIB): SIB estimates cognitive aptitudes and other skills in severely impaired dementia patients. Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-Plus (CIBIC-Plus): CIBIC-Plus is a clinical tool used to evaluate cognition, behavior, and activities of daily living in patients with AD. Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD): DAD is a 10-domain, 40-item instrument that measures basic and instrumental activities of daily living. Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS): PSMS is a self-assessment questionnaire for dementia patients. Neuro-psychiatric Inventory (NPI): NPI is a 10-item assessment of behavioral symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, and agitation/aggression, with decreasing scores indicating clinical improvement.

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT OPTIONS

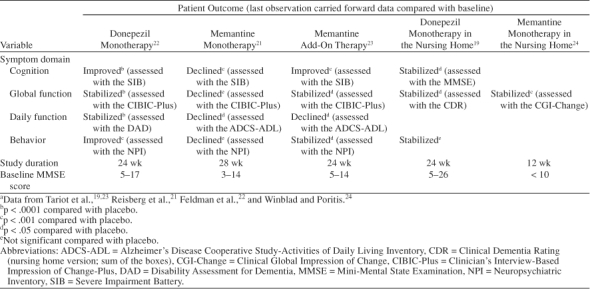

ChEIs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of mild to moderate AD and are recommended as standard therapy.25 The 3 most widely prescribed drug treatments for mild to moderate AD are the second-generation ChEIs donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine. Donepezil was approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD in 1996. Several clinical trials provide evidence for donepezil's efficacy in treating the cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms that affect patients in the mild, moderate, and severe stages of AD.12,14,16,20,22 Rivastigmine was approved in 2000 and has clinical evidence suggesting treatment benefit in mild to moderate AD.13,17,26 Galantamine was approved in 2001 and also has clinical data to show that it benefits patients with mild to moderate AD.18,27 Memantine, a noncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist, has demonstrated clinical efficacy21 and was approved in 2003 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Table 1 summarizes the findings from published, prospective studies in patients with moderate to severe AD.

Table 1.

Summary of Pharmacologic Efficacy in Patients With Moderate to Severe Alzheimer's Diseasea

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Rivastigmine and galantamine

Rivastigmine and galantamine are approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD. No prospective clinical trials of these agents have reported efficacy in patients with moderate to severe AD. Post hoc analyses of patients with moderate28 and “advanced moderate”29,30 dementia have reported clinical efficacy. However, these preliminary findings remain to be confirmed in well-designed placebo-controlled studies enrolling patients with moderate to severe AD.

Donepezil

Donepezil is approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD and is, to date, the only ChEI that has been studied prospectively in patients with moderate to severe AD. In a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of donepezil treatment,22 cognition improved significantly on the MMSE and the SIB. Global function, as measured by the CIBIC-Plus, stabilized in the donepezil group, while in the placebo group, global function declined throughout the study.22 IADLs and ADLs were also used to assess daily function. DAD scores were stable for the donepezil group compared with the placebo group, in which DAD scores declined. Similarly, the modified Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale showed a significant improvement in the donepezil group compared with placebo, as did the PSMS. Behavioral symptoms, as measured by the NPI, improved significantly with donepezil treatment.22 Item analysis of these NPI data showed improvement in favor of donepezil for all items, with significant treatment differences for depression/dysphoria, anxiety, and apathy.

The efficacy of donepezil in AD patients residing in nursing homes was studied in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, 24-week clinical trial19 conducted at 27 sites across the United States. In this study, the majority of donepezil-treated patients (88%) and placebo-treated patients (82%) had moderate to severe AD (MMSE score of 5–20), with the remainder having mild AD (MMSE score of 21–26). Patients were generally older, had more comorbid illnesses and higher concomitant medication usage, and exhibited more severe symptoms than patients enrolled in prior clinical studies of donepezil.12,14,20 Nevertheless, global function and cognition were stabilized in these patients after 24 weeks of treatment with donepezil.19

ChEIs are approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD. The clinical trial data for donepezil, however, also demonstrate efficacy in patients with moderate to severe AD. Patients in these later stages of AD had improved cognition, stabilized function, and improved behavioral symptoms after treatment with donepezil. The body of clinical evidence for donepezil shows that it provides significant benefits for patients in all stages of AD (mild, moderate, and severe).

Memantine

Memantine is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. A 28-week study21 showed that cognition, as measured by the SIB, declined less in memantine-treated patients than in the placebo group. MMSE scores did not show a difference in cognition between memantine and placebo treatment. Measures of function in memantine-treated patients also showed less than expected decline. Global function, as measured by the CIBIC-Plus and Global Deterioration Scale, declined less for the memantine group than the placebo group. Assessment of ADLs by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL; modified for severe dementia) and Functional Assessment Staging scale showed less decline for the memantine group than the placebo group.21 Behavior was measured by the NPI and was not improved over placebo in patients treated with memantine.21

A 3-month clinical trial of memantine in nursing home patients with severe dementia24 showed treatment benefit compared with placebo on the global function measure, the Clinical Global Impression of Change scale, and the care dependence subscale of the Behavioral Rating Scale for Geriatric Patients. However, this trial was too short to provide evidence for long-term benefit from memantine treatment in patients with severe dementia.24

Memantine monotherapy provides cognitive and functional benefits for patients with moderate to severe AD, since patients tended to have less than expected decline. Studies of memantine monotherapy have not shown treatment benefit for the behavioral symptoms of AD.

Memantine Add-On Treatment

In patients with moderate to severe AD who were receiving stable, long-term donepezil therapy (mean of 2.45 years), adjunctive memantine treatment improved cognition, ADLs, global function, behavior, and care dependence.23 Over the 6-month course of this trial, cognition, as measured by the SIB, was improved from baseline for patients receiving adjunctive treatment, while patients receiving donepezil monotherapy declined slightly. Daily functioning was assessed by the ADCS-ADL and declined less in the group receiving adjunctive treatment than in the group receiving donepezil monotherapy. Global function, as measured by mean CIBIC-Plus scores, was stabilized in both groups, with 55% of the adjunctive treatment group and 45% of the donepezil monotherapy group rated as improved or unchanged. Behavioral symptoms, as assessed by the NPI, were stabilized for the adjunctive treatment group compared with the donepezil monotherapy group, which declined slightly. The Behavioral Rating Scale for Geriatric Patients care dependency subscale showed that patients receiving adjunctive treatment had a more slowly increasing need for care than patients receiving donepezil monotherapy.23

Patients who received memantine adjunctive to stable, long-term donepezil treatment had improved cognition, function, and behavioral symptoms compared with patients receiving donepezil monotherapy. This 6-month study23 suggests that adjunctive memantine treatment may offer benefit to patients with advanced AD who have been stabilized on long-term ChEI therapy.

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT OF MODERATE TO SEVERE ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Treatment Expectations

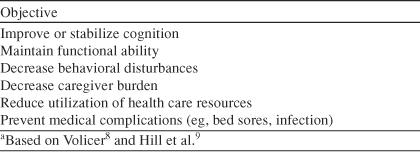

Table 2 summarizes the clinically and socially meaningful outcomes for patients with more advanced dementia and their families.

Table 2.

Treatment Objectives in Advanced Stages of Alzheimer's Diseasea

Clinical outcomes

ChEIs provide treatment benefits for the cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms of mild to moderate AD. However, decline in these symptom domains is an inevitable consequence of the progressive neurodegeneration in AD. Treatment with ChEIs may lead to clinical stabilization of AD, and this stabilization or slowed decline should be considered treatment success.31 Meaningful clinical treatment objectives in the more advanced stages of AD include maintaining daily function, decreasing behavioral symptoms, and reducing or delaying emergence of medical complications.8 Long-term symptomatic benefits in cognition, function, and behavioral symptoms may help patients with advanced AD maintain some of their independence.

Memantine add-on therapy improves cognition while stabilizing both global function and behavior.23 Memantine monotherapy shows decreased decline in cognition, global function, daily function, and behavioral symptoms.21 Stabilization of global function was observed for memantine-treated patients with severe dementia.24

Social outcomes

Deterioration in the daily functioning of an AD patient places great burden on caregivers. Caregivers of patients receiving ChEI therapy have been shown to spend less time giving care and to have lower indirect and direct health care costs, the results of lost time at work and the stress of providing care.32–34 In patients with moderate to severe AD, the disease stages requiring the most assistance, caregivers of those receiving donepezil reported spending 52 minutes per day less providing ADL assistance than caregivers of placebo-treated patients.32 In an economic evaluation,35 donepezil treatment in patients with moderate to severe AD resulted in cost savings. Most of the cost savings could be attributed to less need for residential care by patients and less need for caregivers to spend time assisting with ADLs.35 A recent study36 in the United Kingdom found that donepezil improved cognitive and functional outcomes for patients with mild to moderate AD. Although the study was not statistically powered to measure cost outcomes, it reported no significant difference in costs under the U.K. National Health Service for patients receiving either donepezil or placebo treatment. The potential time and cost saved by ChEI treatment provide needed relief for caregivers and reduce the economic burden on health care resources.

Although most families prefer to keep AD patients at home as long as possible,37 increasing cognitive decline, functional impairment, and behavioral symptoms result in nursing home placement. Treatments that delay costly nursing home placement are highly desirable. A prospective follow-up study in patients with mild to moderate AD revealed that dementia-related nursing home placement was delayed by nearly 2 years with donepezil treatment.38 In a retrospective analysis performed by Lopez et al.,39 ChEI treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of nursing home admission. No studies to date have reported the effects of memantine treatment on the risk of nursing home placement. Delaying nursing home placement helps keep patients in the community longer and reduces the social costs of care.

TOLERABILITY OF TREATMENT IN ADVANCED ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Studies of donepezil report the cholinomimetic effects common to ChEI therapy, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. In patients with moderate to severe AD, these effects occurred more frequently in patients receiving donepezil than in those receiving placebo.22 Generally, adverse events were mild in severity. Likewise, adverse events were similar between treatment groups in nursing home patients, where the majority of adverse events were transient and mild or moderate in severity.19 All patients in the moderate to severe AD study22 and more than 80% of patients in the nursing home study19 had at least 1 comorbid condition. In both studies, 95% of patients were receiving concomitant medications.

A study of memantine in patients with moderate to severe AD21 reported that the frequency of adverse events was similar between treatment groups. Most adverse events were reported as mild to moderate in severity. Agitation, urinary incontinence, urinary tract infection, insomnia, and diarrhea were the most frequently occurring adverse events.21 Likewise, the frequency of adverse events was reported as similar between treatment groups for a study of memantine in care-dependent patients with severe dementia.24

In a study23 of patients with moderate to severe AD who received memantine adjunctive to stable, long-term donepezil treatment, adverse events were reported to be mild to moderate in severity. Generally, the frequency of adverse events was reported as similar between the group receiving adjunctive treatment and the group receiving donepezil monotherapy. Confusion, headache, and constipation occurred more frequently in the adjunctive treatment group than in the donepezil monotherapy group. Diarrhea, fecal incontinence, and nausea occurred more frequently in the donepezil monotherapy group than in the adjunctive treatment group.

Although direct comparisons of memantine and ChEIs have yet to be made, both memantine and donepezil appear to be well tolerated in patients with moderate to severe AD as well as in patients with dementia who reside in nursing homes.

SUMMARY

Patients with moderate to severe AD have shown consistent clinical benefit from donepezil monotherapy as well as from memantine treatment adjunctive to stable, long-term donepezil therapy. As monotherapy, donepezil improves cognitive and behavioral symptoms while stabilizing function in patients with moderate to severe AD. Memantine monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe AD has shown cognitive and functional benefit. Behavioral symptoms, however, were not improved with memantine monotherapy.

Adding memantine to ChEI therapy in the advanced stage of AD appears to benefit patients. Patients with moderate to severe AD who received stable, long-term donepezil therapy followed by memantine add-on treatment had improved cognition, function, and behavior. This study23 suggests that patients who are likely to experience good tolerability and efficacy from donepezil therapy may also respond well to adjunctive memantine treatment.

Finally, a growing need exists in primary care settings for increased emphasis on treatment and management of AD across the disease continuum. More specifically, in moderate to severe AD, recent pharmacologic studies have shown benefit in cognition, function, and behavior. Enhanced understanding and application of these findings will enable beneficial treatment of moderate to severe AD.

Drug names: donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Reminyl), memantine (Namenda), rivastigmine (Exelon).

Footnotes

Dr. Forchetti received honoraria from Eisai and Pfizer for this study.

Dr. Forchetti has served as a consultant for Eisai and Pfizer and has received honoraria from Eisai, Pfizer, Forest, Janssen, and Johnson & Johnson.

REFERENCES

- Ernst RL, Hay JW. Economic research on Alzheimer disease: a review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997 11suppl 6. 135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschstein R. Disease-specific estimates of direct and indirect costs of illness and NIH support. Fiscal year 2000 update. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://ospp.od.nih.gov/ecostudies/COIreportweb.htm. Accessed October 31, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United States General Accounting Office. Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Alzheimer's Disease: Estimates of Prevalence in the United States. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, and Albert MS. et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons: higher than previously reported. JAMA. 1989 262:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Fox PJ. The world-wide impact of dementia: projections of prevalence and costs. In: Mayeux R, Christen Y, eds. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease: From Gene to Prevention. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. 1999 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D. An integrated approach to the management of Alzheimer's disease: assessing cognition, function and behaviour. Eur J Neurol. 1998 5suppl 4. S9–S17. [Google Scholar]

- Mega MS, Cummings JL, and Fiorello T. et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996 46:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer L. Management of severe Alzheimer's disease and end-of-life issues. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:377–391. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JW, Futterman R, and Duttagupta S. et al. Alzheimer's disease and related dementias increase costs of comorbidities in managed Medicare. Neurology. 2002 58:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CA, Gold DP, and Shulman KI. et al. Factors determining the decision to institutionalize dementing individuals: a prospective study. Gerontologist. 1993 33:714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon J, Cheng CK, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer's disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:206–216. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.6.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Rossor M, and Hecker J. and the International Donepezil Study Group. et al. The effects of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease: results from a multinational trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999 10:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey-Bloom J, Anand R, Veach J. for the ENA 713B352 Study Group. A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ENA 713 (rivastigmine tartrate), a new acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1998;1:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mohs RC, Doody RS, and Morris JC. et al. A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients [published erratum in Neurology 2001;57:1942]. Neurology. 2001 57:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT. Donepezil Study Group. The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease: results of a US multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia. 1996;7:293–303. doi: 10.1159/000106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Farlow MR, and Doody RS. Donepezil Study Group. et al. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998 50:136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosler M, Anand R, and Cicin-Sain A. et al. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999 318:633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Solomon PR, and Morris JC. Galantamine USA-10 Study Group. et al. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. Neurology. 2000 54:2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Cummings JL, and Katz IR. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease in the nursing home setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 49:1590–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Engedal K, and Soininen H. Donepezil Nordic Study Group. et al. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology. 2001 57:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Doody R, and Stoffler A. et al. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003 348:1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease [published erratum in Neurology 2001;57:2153]. Neurology. 2001 57:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Farlow MR, and Grossberg GT. et al. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 291:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Poritis N. Memantine in severe dementia: results of the 9M-Best Study (benefit and efficacy in severely demented patients during treatment with memantine) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:135–146. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199902)14:2<135::aid-gps906>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Stevens JC, and Beck C. et al. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 56:1154–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow MR, Hake A, and Messina J. et al. Response of patients with Alzheimer disease to rivastigmine treatment is predicted by the rate of disease progression. Arch Neurol. 2001 58:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, and Wessel T. Galantamine USA-1 Study Group. et al. Galantamine in AD: a 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a 6-month extension. Neurology. 2000 54:2261–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doraiswamy PM, Krishnan KR, and Anand R. et al. Long-term effects of rivastigmine in moderately severe Alzheimer's disease: does early initiation of therapy offer sustained benefits? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002 26:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesa R, Davidson M, and Kurz A. et al. Galantamine provides sustained benefits in patients with “advanced moderate” Alzheimer's disease for at least 12 months. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003 15:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Hock C, and Farlow M. et al. Galantamine provides broad benefits in patients with “advanced moderate”Alzheimer's disease (MMSE ≤ 12) for up to 6 months. Int J Clin Pract. 2002 56:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Gauthier S. Stabilization approaches to Alzheimer's disease. In: Gauthier S, ed. Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer's Disease. London, UK: Martin Dunitz Publishers. 1996 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. Donepezil MSAD Study Investigators Group. et al. Efficacy of donepezil on maintenance of activities of daily living in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease and the effect on caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 51:737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M, Wilcock GK, and van Baelen B. et al. The effects of galantamine treatment on caregiver time in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003 18:942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Winblad B, and Engedal K. et al. An economic evaluation of donepezil in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: results of a 1-year, double-blind, randomized trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003 15:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. Donepezil Nordic Study Group. et al. Economic evaluation of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004 63:644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney C, Farrell D, and Gray R. et al. Long-term donepezil treatment in 565 patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD2000): randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2004 363:2105–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlawish JH, Klocinski JL, and Merz J. et al. Caregivers' preferences for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2000 55:1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, and McRae T. et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 51:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, and Wisniewski S. et al. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment alters the natural history of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002 72:310–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]