Abstract

Background: This open-label pilot study investigated whether the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder with frequent psychiatric comorbidity.

Method: Fifteen patients meeting Rome I criteria for IBS were administered open-label citalopram (20–40 mg/day) for 12 weeks. The study was conducted from October 2000 to August 2001.

Results: Twelve (80%) of the 15 subjects reported a ≥ 50% decrease in the presence of abdominal pain, 10 (67%) reported a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity of the symptom, and 12 (80%) reported a ≥ 50% reduction in the frequency of the symptom. Approximately one half of the patients met criteria for remission (≥ 70% improvement) of abdominal pain.

Conclusion: Results of this pilot study suggest that large controlled trials are needed to further evaluate the efficacy of SSRIs such as citalopram for the treatment of IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a gastrointestinal (GI) disorder occurring in 10% to 24% of the general population,1,2 accounts for 12% of all visits to primary care physicians and 28% of all visits to gastroenterologists.3,4 The disorder is characterized by chronic abdominal discomfort with altered bowel habits that cannot be explained by structural or biochemical abnormalities.5 IBS can result in significant morbidity, with patients reporting 3 times as many absences from school and work compared to those without the disorder.6

Psychiatric comorbidity is common in patients with IBS; approximately 70% to 90% of individuals who seek treatment for IBS also show symptoms of a psychiatric disorder,7 including panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depressive disorder. Conversely, individuals with IBS symptoms who do not seek treatment, an estimated 50% to 86% of the afflicted population,1 tend not to exhibit psychiatric symptomatology.7

While the etiology of IBS remains unclear, there is considerable evidence of a pathophysiologic linkage between the brain and the enteric nervous system.8 Stress is known to exacerbate bowel symptoms in patients with IBS and healthy subjects,9–11 and GI symptoms, such as nausea, abdominal distress, and weight gain/loss, frequently are observed in patients with mood and anxiety disorders, suggesting a common etiologic pathway between psychiatric and at least some GI disorders.12 In particular, symptoms of IBS are reported to occur frequently in psychiatric patients. Masand et al.13–15 observed IBS in 27% of individuals with major depression,13 59% of those with dysthymia,14 and 58% of patients with double depression (defined as major depression plus dysthymia).15 Similarly, Tollefson et al.16 reported that 37% of patients with generalized anxiety disorder met criteria for IBS, and several studies17–19 have reported a correlation between IBS and panic disorder. Additionally, Gupta et al.20 observed IBS in 19% of patients with schizophrenia, and Masand and colleagues21 have reported that IBS occurs frequently among patients seeking treatment for alcohol abuse or dependence.

The frequent comorbidity of psychiatric illness and the absence of an identifiable organic cause of IBS raise the possibility that underlying mood or anxiety disorders may be causally related to IBS and that antidepressant and antianxiety treatment thus may alleviate such symptoms. Moreover, there is some evidence that serotonin (5-HT) receptors, particularly 5-HT3 and 5-HT4, may mediate sensory and reflex responses to GI stimuli and play a role in emesis, diarrhea, eating behavior, abdominal pain, and GI sensorimotor reflexes.22 It has been suggested that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), some of which may have some activity at the 5-HT3 receptor,23 may improve symptoms of IBS and depression in comorbid patients.24 Hence, this pilot study was performed to evaluate whether treatment with the SSRI antidepressant citalopram improves IBS symptoms.

METHOD

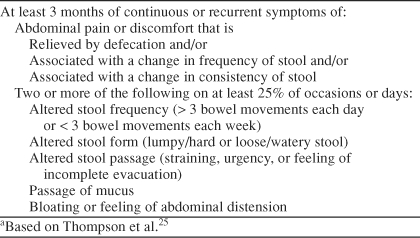

Individuals aged 18 to 65 years experiencing GI symptoms for ≥ 2 days a week for > 6 months and with a diagnosis of IBS according to the Rome I criteria25 (Table 1) were eligible for entry into the study. GI symptoms in study participants could not be attributable to lactose intolerance, nor could participants have a history or current diagnosis of heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias, glaucoma, urinary retention, pregnancy, alcoholism, or previous surgery that would interfere with the interpretation of symptoms (e.g., active thyroid disease, scleroderma, vasculitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic bowel, GI bypass or resection, or malabsorption syndromes). Furthermore, female study participants were required to use a medically acceptable method of birth control throughout the study, and all participants were required to have access to a touch-tone telephone. Additional exclusion criteria included use of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor within the prior 2 weeks, active history of alcohol or substance abuse in the preceding 6 months, history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and active suicidal or homicidal ideation or intent. The study was conducted from October 2000 to August 2001.

Table 1.

Rome 1 Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndromea

The institutional review board at each participating institution (outpatient psychiatric offices) approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent and underwent a physical examination and laboratory evaluations that included complete blood count, blood chemistry analysis, fecal occult blood examination, and flexible sigmoidoscopy to support the diagnosis of IBS. At baseline, all patients were administered a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV41 to determine whether comorbid psychiatric illness was present. Patient impressions of improvement were evaluated using the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I)26 scale during weekly visits. The CGI-I is rated from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse).

All IBS patients enrolled in the 12-week open-label study were treated initially with 20 mg/day of citalopram. After 4 weeks, the dose of citalopram could be increased to 40 mg/day in patients with a partial response to the initial dose.

Patients self-rated their symptom improvement using a telephone-based interactive voice response system.27–29 All subjects were required to complete daily diary entries of their GI symptoms for a baseline week and for 12 weeks during treatment with study medications. Patients were instructed to call daily before bedtime, using a toll-free number. They entered a password and identification number and then recorded their diary entries in response to previously recorded questions (e.g., “Did you experience abdominal pain or discomfort today? If yes, press 1; if no, press 2.”).

Relative changes from baseline in the severity of abdominal pain/discomfort and other IBS symptoms (constipation, diarrhea, incomplete emptying, and bloating/ abdominal distension) were monitored clinically, using an ordinal scale rated from 1 to 9, with 1 being mild pain/ discomfort and 9 being very severe pain/discomfort. Frequency of abdominal pain was evaluated on a 4-point ordinal scale (1 = pain or discomfort present only occasionally, 2 = pain or discomfort present less than half the time, 3 = pain or discomfort present more than half the day, and 4 = pain or discomfort almost all day).

Clinical response for dichotomous variables (i.e., symptoms of abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, incomplete emptying, and bloating) was defined prospectively as a ≥ 50% decrease from baseline to last study week in the total or mean number of days in which the symptom was experienced as obtained from daily interactive voice response data. Clinical response for continuous variables (i.e., the severity and/or frequency of the symptoms and the general level of stress they caused) was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline week to the last study week in the total or mean symptom severity or frequency scores. Remission of IBS symptoms was defined as a ≥ 70% improvement from baseline to the end of the study period. The proportion of patients who experienced treatment response or remission of symptoms was assessed using the t test.

RESULTS

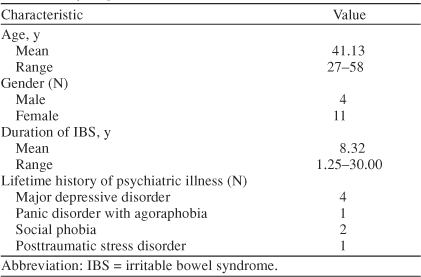

Fifteen patients (4 men and 11 women, mean age of 41.1 years) with IBS were enrolled in the study. Eight patients had a lifetime history of psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (N = 4), panic disorder with agoraphobia (N = 1), social phobia (N = 2), and posttraumatic stress disorder (N = 1). Mean duration of IBS was 8.3 years, ranging from 15 months to 30 years (Table 2). Over the 12-week study, the mean dose of citalopram was 33.3 mg/day.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population (N = 15)

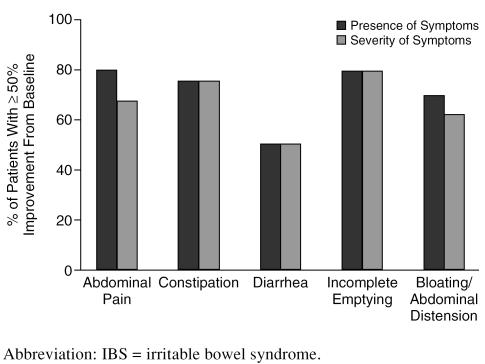

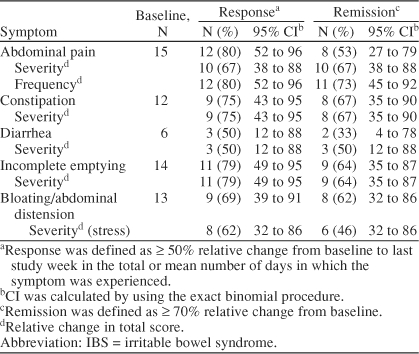

By study end, 12 (80%) of 15 subjects responded to treatment (defined as a ≥ 50% decrease from baseline to last study week in the total or mean number of days in which the symptom was experienced) for the symptom of abdominal pain. In addition, 10 (67%) and 12 (80%) patients experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity and the frequency of abdominal pain, respectively. For constipation, 9 (75%) of 12 subjects reported a ≥ 50% decrease in the presence of the symptom, and an equal number experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity of constipation. Of 6 subjects reporting diarrhea, 3 (50%) responded to treatment, and 3 experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity of diarrhea. Furthermore, 11 (79%) of 14 subjects reported a ≥ 50% decrease in the presence of incomplete emptying, and an equal number experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity of that symptom. Nine (69%) of 13 subjects reported a ≥ 50% decrease in the presence of bloating/abdominal distension, while 8 (62%) subjects experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in the severity of that symptom (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Response (≥ 50% improvement) of IBS Symptoms to Citalopram Treatment

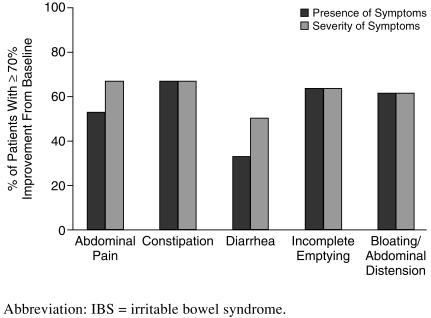

Using the stringent criteria for remission (≥ 70% improvement from baseline), 8 (53%) of 15 subjects experienced remission of abdominal pain. The symptom of constipation was remitted in 8 (67%) of 12 subjects, diarrhea was remitted in 2 (33%) of 6 subjects, incomplete emptying was remitted in 9 (64%) of 14 subjects, and bloating/abdominal distention was remitted in 8 (62%) of 13 subjects (Figure 2). Response and remission scores for all symptoms are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Remission (≥ 70% improvement) of IBS Symptoms With Citalopram Treatment

Table 3.

Improvement in IBS Symptoms After 12 Weeks of Citalopram Treatment

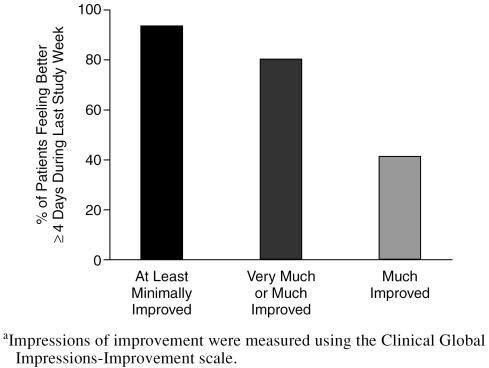

After 12 weeks of citalopram treatment, symptoms were at least minimally improved relative to baseline for ≥ 4 days during the last study week in 14 (93%) patients, as measured by CGI-I scores. Symptoms were very much or much improved for 12 (80%) of the subjects (6 [40%] and 6 [40%] patients, respectively) (Figure 3). Eight (53%) of the subjects had a dosage increase of the citalopram to 40 mg daily while the others remained on a dosage of 20 mg daily.

Figure 3.

Patients' Impressions of Improvement After 12 Weeks of Citalopram Treatmenta

Citalopram was generally well tolerated by patients in the study. The most frequently reported side effects were asthenia, sedation, increased dream activity, reduced salivation, and constipation. No patient discontinued treatment because of adverse events.

DISCUSSION

Although the presence of psychiatric illness seems to influence how IBS is experienced and acted upon by the patient,1 the etiology and treatment of IBS remain controversial. Comorbidity of IBS with psychiatric disorders and other functional gastrointestinal disease is high, giving rise to multiple theories, including that IBS may result from a combination of psychological and physiologic factors.30

Treatment of IBS with antidepressants seems to effect global improvements, although the evidence comes from a small number of trials and merits further inquiry. Among the few double-blind trials, Myren and colleagues31,32 more than 20 years ago reported that the tricyclic antide-pressant trimipramine alleviated IBS-associated abdominal pain, nausea, sleeplessness, and depression. Clouse et al.33 performed a retrospective review of 5 years of anti-depressant therapy in 138 IBS patients and found that improvement and complete remission in bowel symptoms occurred in 89% and 61% of patients, respectively, during therapy with tricyclic antidepressants and other anti-depressants (e.g., trazodone, amoxapine). In this series of patients, the median antidepressant dose was lower than typically required to achieve antidepressant effects, and the presence or absence of psychiatric symptoms was not correlated with treatment response. More recently, the potential effectiveness of the SSRI paroxetine in the management of IBS symptoms has been evaluated in a pilot open-label study,34 and anecdotal reports have suggested benefits with paroxetine,35 fluvoxamine,36 and mirtazapine.37

In the present open-label study, we used Rome I criteria to diagnose IBS, plus a detailed medical workup that included flexible sigmoidoscopy to exclude the presence of significant GI illness as the source of distress. Psychiatric diagnoses were made using a structured psychiatric interview, and depressive symptoms were monitored using the CGI-I scale to control for psychiatric illness as a confounding variable. A daily automated telephone interactive voice response system to collect patients' assessments of symptoms was used to minimize the recall biases associated with retrospective reports. In this setting, citalopram was found to be effective and well tolerated in easing abdominal pain, as well as constipation, diarrhea, the sensation of incomplete emptying, and bloating/ abdominal distension, compared with baseline measures for these cardinal symptoms of IBS.

It remains unclear whether the mechanism by which citalopram led to improvements in IBS symptoms is separate from its antidepressant properties. In the study, 80% of subjects responded to treatment for abdominal pain, yet only 53% of patients in the study had a lifetime history of mood or anxiety disorders. Remission from abdominal pain was achieved by 53% of subjects, but not necessarily all those who attained remission had comorbid psychiatric illness. As the sample size was small in this pilot study, more information was not available. Thus, elucidation of the mechanism of action of citalopram in IBS will require further exploration.

Findings from this pilot study suggest that citalopram may be an effective treatment for abdominal pain and other symptoms associated with IBS.

This pilot study has several limitations, which include a small sample size (N = 15) and lack of a placebo-controlled design. Cautious interpretation is required given the inclusion in this study of patients both with and without psychiatric comorbidity. This study also did not collect data on other mood-altering drugs the patients were taking or past treatment with an SSRI. This study by virtue of its small sample size is unable to provide information regarding a dose-related response of the IBS symptoms to a higher (40 mg/day) citalopram dosage. Additionally, 2 controlled trials, 1 using fluoxetine (N = 40) and the other using paroxetine (N = 38 paroxetine group; N = 43 placebo group), did not reveal the SSRIs to be remarkably effective in alleviating the symptoms of IBS.38,39 At the time we designed and conducted this pilot study, fluoxetine and paroxetine studies in IBS were not published. As these preliminary results appear promising, larger placebo-controlled trials with adequate power are warranted to evaluate further the potential efficacy of SSRIs such as citalopram, or its active enantiomer, escitalopram,40 for the treatment of IBS.

Drug names: citalopram (Celexa and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac, Symbyax, and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), trazodone (Desyrel and others), trimipramine (Surmontil).

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by Forest Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, Mo.

Dr. Masand has served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Health Care Technology, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Organon, Pfizer, and Wyeth; has received grant/ research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, Janssen, and Wyeth; has served on the speakers boards of AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, and Wyeth; and is a stockholder of psychCME Inc. Dr. Gupta has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and Shire Richwood; has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Forest, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Johnson & Johnson, and Neurochem; has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline; and has served on the speakers or advisory boards of Forest, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Shire Richwood. Drs. Schwartz, Virk, Hameed, and Kaplan report no other affiliation or financial relationship relevant to this article.

REFERENCES

- Lynn RB, Friedman LS. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1940–1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, and Van Dyke C. et al. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991 101:927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Drossman DA. Survey of the AGA membership relating to patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1282–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(87)91099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton N. Functional bowel disorders survey. Participate. 1997;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Read NW. ed. The neurotic bowel: a paradigm for the irritable bowel syndrome. In: Read NW, ed. Irritable Bowel Syndrome, New Insights Into Pathophysiology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications. 1991 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Li Z, and Andruzzi E. et al. US householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders: prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993 38:1569–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, McKee DC, and Sandler RS. et al. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome: a multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988 95:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA. Emerging disease model for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Med. 1999;107:12S–19S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Sandler RS, and McKee DC. et al. Bowel patterns among subjects not seeking health care: use of a questionnaire to identify a population with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1982 83:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydiard RB. Anxiety and the irritable bowel syndrome. Psychiatr Ann. 1992;22:612–618. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, and Robinson JC. et al. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992 33:825–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydiard RB, Falsetti SA. Experience with anxiety and depression treatment studies: implications for designing irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:65S–73S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand PS, Kaplan DS, and Gupta S. et al. Major depression and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a relationship? J Clin Psychiatry. 1995 56:363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand PS, Kaplan DS, and Gupta S. et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and dysthymia: is there a relationship? Psychosomatics. 1997 38:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand PS, Kaplan DS, and Gupta S. et al. Relationship between irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and double depression (dysthymia plus major depression). Depression. 1995-1996 3:303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson GD, Tollefson SL, and Pederson M. et al. Comorbid irritable bowel syndrome in patients with generalized anxiety and major depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1991 3:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lydiard RB, Laraia MT, and Howell EF. et al. Can panic disorder present as irritable bowel syndrome? J Clin Psychiatry. 1986 47:470–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes R Jr, Cook B, and Garvey M. et al. Reduction of gastrointestinal symptoms following treatment for panic disorder. Psychosomatics. 1990 31:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DS, Masand PS, Gupta S. The relationship of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and panic disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8:81–88. doi: 10.3109/10401239609148805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Masand PS, and Kaplan D. et al. The relationship between schizophrenia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Schizophr Res. 1997 23:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand PS, Sousou AJ, and Gupta S. et al. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and alcohol abuse or dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1998 24:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read NW, Gwee KA. The importance of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in the gut. Pharmacol Ther. 1994;62:159–173. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchelli A, Santagostino-Barbone MG, and Barbieri A. et al. The interaction of antidepressant drugs with central and peripheral (enteric) 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1995 114:1017–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse RE. Antidepressants for functional gastrointestinal syndromes. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:2352–2363. doi: 10.1007/BF02087651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WG, Creed F, and Drossman DA. et al. Functional bowel disease and functional abdominal pain. Gastroenterol Int. 1992 5:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Dept Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM) 76–338. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Mental Health. 1976 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Greist JH, and Jefferson JW. et al. Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Comput. 1999 16:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Taylor LH, and Dottl SL. et al. A computer-administered telephone interview to identify mental disorders. JAMA. 1997 278:905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Kobak KA, and Taylor LV. et al. Administration of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale using interactive voice response technology. MD Comput. 1998 15:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myren J, Groth H, and Larssen SE. et al. The effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982 17:871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myren J, Lovland B, and Larssen SE. et al. A double-blind study of the effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984 19:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, and Geisman RA. et al. Antidepressant therapy in 138 patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year clinical experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994 8:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masand PS, Gupta S, and Schwartz TL. et al. Does a preexisting anxiety disorder predict response to paroxetine in irritable bowel syndrome? Psychosomatics. 2002 43:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch MA, Louie AK. Paroxetine and irritable bowel syndrome [case report] Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1523–1524. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1523-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel NP, Lydiard RB, Crawford M. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with fluvoxamine [letter] Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:711–712. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.711b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG. Irritable bowel syndrome and mirtazapine [letter] Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1341–1342. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1341-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken SD, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. The selective serotonin inhibitor fluoxetine does not change rectal sensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:219–228. doi: 10.1053/cgh.2003.50032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas G, Beaves M, and Wang J. et al. Paroxetine to treat irritable bowel syndrome not responding to high fiber diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 99:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyttel J, Bogeso KP, and Perregaard J. et al. The pharmacologic effect of citalopram resides in the (S)-(+)-enantiomer. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1992 88:157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, and Gibbon M. et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 1996 [Google Scholar]