ABSTRACT

To assess levels of acute stress symptoms (ASS) and prevalence of acute stress disorder (ASD) in an Israeli civilian sample and examine sociodemographic and war exposure predictors of ASS and ASD. A telephone survey was conducted in the fourth week of the 7 October war with a random sample of 199 Jewish and 194 Arab adult residents from areas of lower Galilee and Acre, Herzliya, and Eilat. ASS and ASD were measured by the Acute Stress Disorder Interview. War exposure and sociodemographic data were collected. 60% of participants met the criteria for ASD. Levels of ASS were relatively high. 21% of the variance in total ASS score was explained by sociodemographic (sex, age, education, ethnicity) and war exposure variables (acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped; subjective sense of danger to self or relatives; property or income damage). The present study revealed significant although mild associations of ASS with war exposure variables (acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped; subjective sense of danger to self or relatives; property or home damage; and employment or income damage). Logistic regression indicated that women were 1.55 times more likely to have ASD than men. Arabs were 2.02 times more likely to have ASD than Jews. The present study stresses the need to construct an acute stress screening procedure to identify individuals with severe acute stress reactions. We call attention to the need to build interventions to reduce these symptoms immediately during warfare to prevent them from developing into chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Strengthening community resilience may reduce the rate of ASS upon exposure to war.

Keywords: acute stress disorder, acute stress symptoms, exposure, war

1. Introduction

Exposure of civilians to war and terrorism may significantly generate mental health problems, enhancing hypervigilance, excessive concern, and fear, often expressed as acute stress symptoms (ASS) and even acute stress disorder (ASD) (Cohen 2008; Kordel et al. 2024; Shrira and Palgi 2024; Sowan and Baziliansky 2024; Yahav and Cohen 2007), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Boyle et al. 2024; Dietch et al. 2019; Kassaye et al. 2023; Levi‐Belz et al. 2024; Palgi et al. 2024). ASD is defined as a traumatic response in the immediate phase following exposure to a traumatic event that endures 3 days to 1 month after trauma exposure (DSM‐5‐TR; American Psychiatric Association 2022).

The diagnosis of ASD requires the presence of the following criteria: (a) direct exposure to threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence; (b) indirect exposure through witnessing the trauma; or (c) learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to trauma or experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s). It also requires the presence of nine or more symptoms from any of five categories of intrusion, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance, and arousal, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event occurred; and that the disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning and cannot be attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition or psychotic disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2022). Empirical evidence shows that ASD is a substantial risk factor in the development of PTSD (Bryant et al. 2015; Cwik et al. 2017; Erçin‐Swearinger et al. 2022; Visser et al. 2017), although several studies revealed that people may develop PTSD in reaction to traumatic events in the absence of ASS or ASD (e.g., see review by Visser et al. (2022)).

Whereas previous studies have examined PTSD as a consequence of war and terror (see recent systematic review by Hoppen et al. (2021)), there has been a limited focus on the prevalence and risk factors of ASS and ASD during or shortly after exposure in cases of sudden warfare. These studies found variable levels of ASS or prevalence of ASD. For example, results of a study in Israel revealed that about 95% of Jewish and 100% of Arab respondents experienced at least one of four ASS criteria (dissociation, reexperiencing, avoidance, arousal), whereas 13% of respondents met ASD criteria in the second Lebanon war (Yahav and Cohen 2007). In a study in the United States, 12.4% of the population had ASS scores above the cutoff for ASD between 9 and 23 days after the 11 September terror attacks (Silver et al. 2002). Another study reported that 7.5% of civilian survivors experienced ASD during the Tunisian revolution in January 2011 (Ouanes et al. 2014). Other research revealed that 24% of war‐exposed individuals had ASD during the outset of an armed conflict between a local terror group and government security forces in the Philippines (Mordeno et al. 2021). Possible factors to explain the varying prevalence of ASS and ASD in different studies can be related to the nature of the traumatic event (e.g., single event vs. continuous), antecedents of the traumatic event (Geoffrion et al. 2022), or cultural differences (Bryant et al. 2011). The few studies that assessed predictors of ASS and ASD in association with sudden warfare reported that a higher risk of ASD was associated with younger age (Cardeña et al. 2005; Yahav and Cohen 2007), female sex (Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024; Bleich et al. 2003; Yahav and Cohen 2007), ethnicity (Yahav and Cohen 2007), previous psychiatric dysfunction, or previous exposure to trauma (Barton et al. 1996; Harvey and Bryant 1999).

While direct exposure to warfare is expected to elicit acute or chronic traumatic responses (Feriante and Sharma 2023), studies found these relations in varied intensities in reaction to indirect exposure (Geoffrion et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2017). For example, PTSD symptoms related to the terrorist attacks on 11 September were found in 4% of individuals living outside the attack sites but indirectly exposed to the tragedy via television (Schlenger et al. 2002). Among residents of New York City who were indirectly exposed to the 11 September attacks, 35% met the criteria for PTSD (North et al. 2011). More media exposure and social media use were associated with higher ASS during the early COVID‐19 outbreak in China (Luo et al. 2021). However, despite these prevalence rates, ASD following indirect exposure to trauma is understudied, especially in warfare cases (Castro et al. 2023). A study among Jewish and Arab adolescents exposed to war showed no differences between Jewish and Arab adolescents in stress reactions (Braun‐Lewensohn and Sagy 2011). Subjective exposure (perceived danger for them and close others) was associated with higher psychological distress among Jewish and Arab adolescents (Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024).

Harakat al‐Muqawama al‐Islamiya (known as Hamas), an Islamic armed movement, was designated by Western countries as a terrorist organisation (Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs 2024). On 7 October 2023, Hamas launched an extensive attack on Israel from the Gaza Strip, setting off the 7 October war (Britannica 2024a). Hamas brutally murdered 1400 Israeli civilians, including entire families with babies and children, in settlements near the Gaza Strip and soldiers in outposts on the border. Hamas also launched multiple missile attacks on cities in Israel. As a result, civilians were injured and murdered, and houses were destroyed. Hamas kidnapped 239 Israeli residents, including babies, children, youths, women, men, soldiers, older people, and people with chronic illnesses (Britannica 2024b). Residents in broad areas of Israel (lower Galilee and Acre in the north and Herzliya in the centre) were exposed to missile attacks that caused a high risk of damage to physical integrity, property, and income. Additionally, citizens in areas generally not exposed to missile attacks (Eilat in the south), including both Jews and Arabs, were deeply affected by these traumatic events, which shattered deeply rooted conceptions of security and represented a direct threat to their and their family's physical integrity. As a consequence, many experienced shock, pain, grief, fear, and uncertainty (Ayalon et al. 2024). The war events created an overwhelming traumatic experience involving a serious threat to the security or physical integrity of all Israeli citizens (Palgi et al. 2024), thus meeting the criteria of exposure in the DSM‐5‐TR (American Psychiatric Association 2022).

To summarise, only a few studies have examined ASS and ASD in reaction to a sudden and traumatic outbreak of war. Examining the prevalence and correlates of ASS and ASD in the 7 October war, which is a unique and unstudied situation that deeply affected all Israeli citizens, including Jewish and Arab Israelis, may deepen our knowledge regarding these responses to warfare. It enables the development of efficient interventions to prevent PTSD. In the present study, we sought to examine rates of ASS, prevalence of ASD, and exposure‐related predictors of ASS among Israeli civilians exposed to war atrocities during the 7 October war.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

This study is a secondary data analysis (Sowan and Baziliansky 2024). Committee for Ethical Research with Humans of the University of Haifa approved this study (Approval No. 376/23). The initial sample included 399 Israeli civilians (women and men, Jews and Arabs) from residential areas of lower Galilee and Acre in the north; Herzliya in the centre, who were exposed to missile attacks, causing high risk to their physical integrity, income, and property (Cohen 2008; Yahav and Cohen 2007); and Eilat in the south, who were affected by the overall threat of war. Many people in this area also experienced financial challenges (Cohen 2008; Yahav and Cohen 2007). Respondents had to be aged 25 or older and have a sufficient understanding of Hebrew or Arabic to complete the survey. None of the participants reported major psychiatric events or cognitive decline in the 6 months prior to the outbreak of the war. Of the 399 individuals who responded, 6 respondents who were directly affected (had a first‐ or second‐degree relative who was injured, killed, or kidnapped) were excluded from the analysis. The final sample included 393 respondents.

Questionnaires were filled out during the fourth week after the war broke out. To obtain the sample, we collaborated with a survey company that maintains a panel of 80,000 people throughout Israel. Several steps were taken to recruit respondents. First, the survey company performed initial filtering, regarding resident area and age, based on participants' existing profiles. After this selection process, the survey company contacted potential participants directly by email or text message with an invitation to participate in the study. This message included an explanation of the study. If potential participants expressed interest in participating, the survey company called them to explain the study in more detail, including its goals and the nature of the survey. After the conversation, the participants signed a consent form and received a link to the questionnaire. The time needed to fill out the questionnaires ranged from 10 to 15 min, and questionnaires were completed in Hebrew or Arabic, the main two languages spoken in Israel. Respondents did not receive any incentive. In addition, the basic demographic variables of the participants who gave informed consent or declined to participate were compared. No significant differences were found between these groups with respect to age, sex, and income. The response rate was 67% for Jewish participants and 61% for Arab participants.

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. About 53% of respondents were men and 47% were women. The respondents' age range was 25–70 years, with an average of 42.36 (SD = 11.61); about 51% were Jews and 49% were Arabs; 60% were married or partnered; and 75% were employed.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N = 393).

| N (%) or M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.36 (11.61) | 25–70 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 208 (52.9) | |

| Female | 185 (47.1) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Jewish | 199 (50.6) | |

| Arab | 194 (49.4) | |

| Education, years | 14.01 (3.20) | 0–25 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or partnered | 237 (60.3) | |

| Nonmarried | 156 (39.7) | |

| Employment | ||

| Full‐time | 221 (56.3) | |

| Part‐time | 71 (18.1) | |

| Retired | 17 (4.3) | |

| None | 84 (21.3) | |

| Income a | ||

| Above average | 157 (39.9) | |

| Average | 75 (19.1) | |

| Below average | 164 (41.7) | |

| Number of children | 1.71 (1.81) | 0–11 |

Average income per household as published by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

2.2. Measures

Sociodemographic variables included sex, age, family status, education level, ethnicity, economic status, employment status, and number of children.

The Acute Stress Disorder Interview (Bryant and Harvey 2000) is a 19‐item structured interview based on DSM‐5‐TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2022) that relate to dissociative symptoms (5 items), reexperiencing (6 items), avoidance (4 items), and arousal (6 items). Respondents were asked to report the extent of symptoms they experienced during the last week (e.g., ‘Avoid thinking about the outbreak’ and ‘Intrusive memories about information and reports related to the outbreak’). Responses were rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The sum was used as an indicator of ASS, ranging from 19 to 95, with a higher score indicating a higher level of ASS. Symptom scores ranged from 6 to 30 for disassociation, 4 to 20 for reexperiencing, 3 to 15 for avoidance, and 6 to 30 for arousal. An ASD diagnosis cutoff score of 56 was adopted based on validation studies (Bryant and Harvey 2000; Edmondson et al. 2010). The measure has good sensitivity (91%) and specificity (93%), and the internal consistency was good in previous studies (Cronbach's α = 0.86–0.94) (Bryant and Harvey 2000; Ye et al. 2020). The questionnaire was translated from English into Hebrew and Arabic (Yahav and Cohen 2007). The internal consistency in the present study was α = 0.94.

2.3. Variables Related to War Exposure

Variables modified from prior research on the second Lebanon war (Cohen 2008; Yahav and Cohen 2007) were used to assess respondents' exposure to war‐related occurrences and events.

Acquaintance Who Was Injured, Killed, or Kidnapped: Respondents were initially asked: ‘Was someone close to you (family member, spouse, friend, and colleague from work or higher education studies) injured, killed, or kidnapped in the war?’ Respondents who answered yes were asked: ‘What is the relationship between you and the person who was injured, killed, or kidnapped?’ The options were first‐degree relative (e.g., spouse, father, son, brother, son‐in‐law, daughter‐in‐law), second‐degree relative (e.g., uncle, cousin, brother‐in‐law, nephew), close friend, acquaintance or distant friend, or other.

Subjective Sense of Danger to Self and Relatives: Respondents were asked: ‘To what extent do you believe you or your relatives were or are in actual danger due to the October 7 war?’ Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Property or Home Damage: Respondents were asked: ‘Since the beginning of the war, how much damage has been caused to your properties (house, garden, car, etc.)?’ Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Employment or Income Damage: Respondents were asked: ‘How much damage has the war caused to your income?’ Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations of sociodemographic and study variables. Pearson correlations between sociodemographic and study variables were examined; then, multiple linear regression analyses to identify predictors of ASS and logistic regression analyses to identify predictors of ASD were conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges of Study Variables

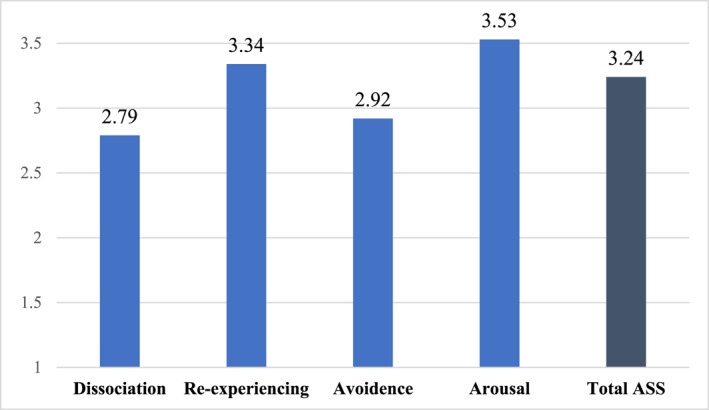

Descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented in Table 2. The mean score for overall ASS was relatively high (M = 3.16, SD = 1.00, with possible range of 1–5). Mean ASS scores by groups of symptoms according to the DSM‐5‐TR (American Psychiatric Association 2022) are shown in Figure 1. The means for avoidance and dissociation were relatively lower than those for reexperiencing and arousal. About 60% (n = 239) of respondents met the criteria for ASD (with a suggested cutoff of 56) (Bryant and Harvey 2000). Table 2 also shows the correlations among the overall ASS score and war exposure variables. Mean ASS score was associated with sex, t (391) = 3.90, p < 0.01; age, r p = −0.16, p < 0.05; ethnicity, t (391) = 0.50, p < 0.01; and years of education (r p = −0.20, p < 0.01). In addition, an analysis of variance was conducted to examine differences in ASS scores across geographic areas (southern, central, northern), analysing Arabs and Jews separately, and it showed no significant differences in ASS levels across areas for Arabs, F(3, 190) = 0.96, p = 0.41, or Jews, F(3, 201) = 1.08, p = 0.36.

TABLE 2.

Means, standard deviations, ranges, and correlations among the study variables (N = 393).

| M (SD) | Actual range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total ASS | 3.24 (1.00) | 1–5 | ||||

| 2. Subjective sense of danger to self and relatives | 2.60 (1.04) | 1–5 | 0.23** | 0.01 | ||

| 3. Property or home damage | 2.80 (1.01) | 1–5 | 0.25** | 0.10 | 0.54** | |

| 4. Employment or income damage | 2.10 (1.30) | 1–5 | 0.23** | 0.04 | 0.14** | 0.09 |

Abbreviations: ASS = acute stress symptoms; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

p < 0.01.

FIGURE 1.

Mean scores of ASS by group and overall. ASS = acute stress symptoms.

3.2. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Predicting Total ASS Score

To identify sociodemographic variables that needed to be controlled in the regression analyses, the associations between the study and sociodemographic variables were assessed using Pearson correlations or chi‐square tests. Sex, age, ethnicity, and years of education were associated with total ASS score (p < 0.05); therefore, they were controlled. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to test associations of sociodemographic and war‐related variables with total ASS.

According to the regression model, 21% of the variance in total ASS score was explained by the study variables: adjusted R 2 = 0.21, F (8, 388) = 13.6, p < 0.001. The sociodemographic variables of sex, age, years of education, and ethnicity were entered together with variables related to war exposure (acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped; subjective sense of danger to self and relatives; property or home damage; and employment or income damage). The sociodemographic variables were significantly associated with total ASS, except age. Sex (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) and ethnicity (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) were significantly related to ASS, with women and Arabs showing higher levels of ASS than men and Jews. In addition, years of education were negatively associated with total ASS score (β = −0.15, p < 0.001), such that more education was associated with lower ASS levels. Four variables related to war exposure were significantly and positively associated with total ASS: having an acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), a subjective sense of danger to self and relatives (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), property or home damage (β = 0.15, p < 0.01), and employment or income damage (β = 0.14, p < 0.01).

3.3. Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting the Risk of ASD

Logistic regression was used to examine the effect of war exposure variables, sex, and ethnicity on the likelihood of having ASD. Table 3 shows the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis indicated that sex and ethnicity were positive and significant predictors of ASD. Regarding sex, women were 1.55 times more likely to have ASD than men. Regarding ethnicity, Arabs were 2.02 times more likely to have ASD than Jews.

TABLE 3.

Logistic regression for predicting the risk of ASD.

| β | SE | Wald | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.44 | 0.22 | 4.03 | 1.55 | 0.42, 0.99 |

| Ethnicity | 0.71 | 0.22 | 10.30 | 2.02 | 0.32, 0.76 |

| Acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped | 0.60 | 0.33 | 3.22 | 1.82 | 0.95, 3.50 |

| Subjective sense of danger to self and relatives | 0.47 | 0.27 | 2.92 | 1.59 | 0.93, 2.72 |

| Property or home damage | 0.32 | 0.11 | 8.04 | 1.38 | 1.11, 1.72 |

| Employment or income damage | 0.23 | 0.09 | 6.69 | 1.26 | 1.06, 1.50 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; ASD = acute stress disorder; OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error.

Regarding exposure to trauma, the analysis indicated that having an acquaintance who was injured, killed, or kidnapped in the war; property or home damage, or employment or income damage were positive and significant predictors of ASD. Respondents who had an acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped had 1.82 times the odds of having ASD than those who did not. Respondents who had property or home damage had 1.38 times higher odds of ASD than those who did not. Finally, respondents who had employment or income damage were 1.26 times more likely to have ASD than those who did not.

4. Discussion

The present study revealed that a high proportion of civilians who were exposed to war atrocities met the criteria for ASD. This high prevalence of ASD can be explained by the sweeping effect of the extreme events of 7 October on all Israelis. Furthermore, due to the small size of Israel's population and the brutality of the event, including 1400 Israeli civilians murdered and 239 kidnapped, many Israelis reported personally knowing at least one person who was killed, kidnapped, or injured or had survived the Hamas attack (Ayalon et al. 2024). Studies in Israel found much lower rates of ASD in previous wars. For example, Yahav and Cohen (2007) reported that during the second Lebanon war among residents of northern Israel, 5.5% of Jewish and 20.3% of Arab respondents met the criteria for ASD. Another study found that 18.9% of citizens residing about 14 km from Israel's northern border during the second Lebanon war were diagnosed with ASD (Boehm‐Tabib 2016).

Only a few studies could be identified on ASS in adults during warfare as a comparison to the present findings. The present results support previous studies that found moderate to high levels of ASS among Israeli citizens during the second Lebanon war (Boehm‐Tabib 2016; Cohen 2008).

Previous studies found that various exposure parameters were associated with levels of ASS, ASD, and PTSD (Boehm‐Tabib 2016; Cohen 2008; Galea et al. 2002; Schlenger et al. 2002). For example, higher perceived proximity to missile attack predicted higher ASS during the second Lebanon war (Cohen 2008). Studies regarding the 11 September attacks in New York and Washington, DC documented that individuals directly exposed to the terrorist attacks manifested PTSD at a rate of 20% (Galea et al. 2002; Schlenger et al. 2002). PTSD was found in 4% of individuals living outside of the attack sites and indirectly exposed to the tragedy via television (Schlenger et al. 2002). Accordingly, the present study revealed significant although mild associations of ASS with war exposure variables (acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped; subjective sense of danger to self and relatives; property or home damage; and employment or income damage; r p = 0.13−0.25, p < 0.05). A possible explanation for the mild associations is that traumatic reactions to the events on 7 October among all Israelis were extremely powerful and had a sweeping effect, thus prompting ASD beyond the degree of exposure. Additionally, due to the global exposure of Israeli civilians to the 7 October war, intrapersonal factors may be more predictive of ASS than exposure variables. For example, previous studies reported positive associations among strong feelings of uncertainty (Nickerson et al. 2023; Nikopoulou et al. 2022), self‐blame, rumination (Bapolisi et al. 2022), avoidance coping (Harvey and Bryant 1999), and levels of psychological distress during warfare. Similarly, a study among Bedouin adolescents during the 7 October war showed a positive association between subjective exposure (sense of danger for them, their close and extended family, their friends, and the people in their community); use of nonproductive coping strategies, mainly avoidance (e.g., behavioural or cognitive disconnection, alcohol consumption); and levels of psychological distress (Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024). Multiple varied factors can influence reactions to warfare, and it was not possible to include them all in the study. We chose to include only sociodemographic (sex, age, education, ethnicity) and war exposure variables (acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped; subjective sense of danger to self and relatives; property and income damage) that were significantly correlated with ASS. We did not include media exposure in our analyses because our preliminary analysis revealed no significant relationships between media exposure and ASS. However, it may be worthwhile to analyse different types of media and their effect on acute and chronic reactions during or shortly after exposure of adults to warfare. Consistent with previous studies (Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024; Boehm‐Tabib 2016; Boehm‐Tabib 2016; Cohen 2008; Neria et al. 2008), women and Arab respondents had a higher risk of ASS and ASD. Differences in the expression of emotions by sex may lead to differences in patterns of reporting, with a manifestation of symptoms among women and internalising symptoms among men (Yahav and Cohen 2007). Accordingly, previous studies found that women may tend to worry more and be more prone to experience traumatic events (McLean and Anderson 2009), putting them at heightened risk of ASS and ASD. Further, in response to aversive events, women are more likely to use emotion‐focused coping, which is often less effective in reducing distress than problem‐focused coping strategies (McLean and Anderson 2009).

The higher ASS score and ASD rate among Arab respondents may be explained by the complex political context that created a problematic paradox: on one hand, their experience of being torn between sympathy and emotionally identifying with the Palestinian struggle and on the other hand, being the target of Hamas attacks despite being Arabs (McLean and Anderson 2009; Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024; Braun‐Lewensohn and Sagy 2011). This could also affect their sense of hope, which was found to predict stress reactions among Arab individuals in Israel in reaction to missile attacks (Yahav and Cohen 2007). A second possibility is that the high level of distress reflects cultural reporting bias. Several studies have demonstrated reporting biases in various populations. For example, Braun‐Lewensohn and Sagy (2011) found higher rates of somatisation among individuals in non‐Western cultures. Consistent with previous studies, a higher level of education predicted less risk of ASS (Lee et al. 2017) and PTSD (Lewis et al. 2014; DiGrande et al. 2008; Helpman et al. 2015). In the present study, a subjective sense of danger to self and relatives was found to be predictive of ASS but not the risk of ASD. These findings indicate the possibility that subjective factors relate to symptoms but are less central to diagnostic criteria. Additionally, the higher risk of ASS and ASD among Arab respondents can be explained by a previously reported tendency to use more emotion‐focused, especially avoidant coping strategies, such as behavioural disengagement, self‐distraction, and denial, to cope with stressful situations, as previously reported (Neria et al. 2013; Abu‐Kaf and Braun‐Lewensohn 2015; Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024), which is associated with higher psychological distress (Braun‐Lewensohn 2012; Al‐Said and Braun‐Lewensohn 2024).

The present study added to our scarce knowledge regarding ASD in response to warfare. Our findings that relatively high levels of ASS were weakly associated with such parameters as having an acquaintance injured, killed, or kidnapped or perceived danger may point to the central role of community resilience, which refers to the success of a community in providing for the needs of its members and the extent to which individuals are helped by their community (Harvey and Bryant 1999). Community resilience may significantly reduce the rate of ASS upon exposure to war (Bonanno et al. 2015). Additionally, the present study stresses the need to construct an acute stress screening procedure, independent of war exposure level, to identify individuals with extreme acute stress reactions. Interventions need to be implemented immediately in wartime. For example, previous studies reported that immediate interventions involving (a) cognitive‐behaviour therapy among survivors of mild brain injury and diagnosed with ASD and (b) a multidisciplinary approach including psychoeducation for survivors of cardiac disease‐induced trauma effectively prevented the development of chronic PTSD (Kimhi et al. 2017; Bryant et al. 2003, 2006, 2008). In accordance with these suggestions, short‐term, trauma‐focused interventions were developed (Six Cs model and ‘psychological inoculation’; Farchi et al. 2024; Farchi and Gidron 2010) that need further assessment of effectivity to reduce acute or chronic stress symptoms. The present findings especially highlight the need to invest in special efforts and resources for women, younger adults, and Arab civilians to prevent high levels of ASS, development of ASD, and progression to chronic PTSD.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a cross‐sectional study; therefore, caution should be exercised when generalising present results to other population groups. Second, the measure of war exposure was developed for the present study in light of the lack of validated tools and the need to capture specific features of the present war. Development and validation of war exposure measures are warranted, employing a mixed‐methods approach that commences with an in‐depth interview to capture diverse modes of exposure. Third, ASS or ASD are transitional states, and their symptoms may decrease and disappear or increase and become a chronic condition (Bryant and Harvey 2000). It is important to conduct follow‐up studies on ASD to understand better the long‐term effects of initial acute stress reactions. Studies on intrapersonal factors that may affect the development of ASD are strongly recommended.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Miri Cohen, an expert in the field of stress and coping, for her generous contribution to the study.

The authors declare equal contribution to the paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Abu‐Kaf, S. , and Braun‐Lewensohn O.. 2015. “Paths to Depression Among Two Different Cultural Contexts: Comparing Bedouin Arab and Jewish Students.” Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology 46, no. 4: 612–630. 10.1177/0022022115575738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Said, H. , and Braun‐Lewensohn O.. 2024. “Bedouin Adolescents During the Iron Swords War: What Strategies Help Them to Cope Successfully With the Stressful Situation?” Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 900. 10.3390/bs14100900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. , Cohn‐Schwartz E., and Sagi D.. 2024. “Global Conflict and the Plight of Older Persons: Lessons From Israel.” American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 32, no. 4: 509–511. 10.1016/j.jagp.2023.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapolisi, A. , Maurage P., Cishugi M. T., et al. 2022. “Predictors of Acute Stress Disorder in Victims of Violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 13, no. 2: 1–5. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2109930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, K. A. , Blanchard E. B., and Hickling E. J.. 1996. “Antecedents and Consequences of Acute Stress Disorder Among Motor Vehicle Accident Victims.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 34, no. 10: 805–813. 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich, A. , Gelkopf M., and Solomon Z.. 2003. “Exposure to Terrorism, Stress‐Related Mental Health and Coping Behaviors Among a Nationally Representative Sample in Israel.” JAMA 290, no. 5: 612–620. 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm‐Tabib, E. 2016. “Acute Stress Disorder Among Civilians During a War and Post‐Traumatic Growth Six Years Later: The Impact of Personal and Social Resources.” Anxiety, Stress & Coping 29, no. 3: 318–333. 10.1080/10615806.2015.105380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. , Romero S. A., and Klein S. I.. 2015. “The Temporal Elements of Psychological Resilience: An Integrative Framework for the Study of Individuals, Families, and Communities.” Psychological Inquiry 26, no. 2: 139–169. 10.1080/1047840X.2015.992677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, S. H. , Upchurch J., Gifford E. J., et al. 2024. “Military Exposures and Gulf War Illness in Veterans With and Without Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 37, no. 1: 80–91. 10.1002/jts.22994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun‐Lewensohn, O. 2012. “Coping Strategies as Mediators of the Relationship Between Chronic Exposure to Missile Attacks and Stress Reactions.” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 5, no. 4: 315–326. 10.1080/19361521.2012.719596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun‐Lewensohn, O. , and Sagy S.. 2011. “Coping Resources as Explanatory Factors of Stress Reactions During Missile Attacks: Comparing Jewish and Arab Adolescents in Israel.” Community Mental Health Journal 47, no. 3: 300–310. 10.1007/s10597-010-9314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britannica . 2024a. Hamas: Palestinian Nationalist Movement. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hamas.

- Britannica . 2024b. Israel‐Hamas War. https://www.britannica.com/event/Israel‐Hamas‐War.

- Bryant, R. A. , Creamer M., O’Donnell M., Silove D., McFarlane A. C., and Forbes D.. 2015. “A Comparison of the Capacity of DSM‐IV and DSM‐5 Acute Stress Disorder Definitions to Predict Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Related Disorders.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 76, no. 4: 391–397. 10.4088/JCP.13m08731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , Friedman M. J., Spiegel D., Ursano R., and Strain J.. 2011. “A Review of Acute Stress Disorder in DSM‐5.” Depression and Anxiety 28, no. 9: 802–817. 10.1002/da.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , and Harvey A. G.. 2000. Acute Stress Disorder: A Handbook of Theory, Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , Moulds M., Guthrie R., and Nixon R. D.. 2003. “Treating Acute Stress Disorder Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury.” American Journal of Psychiatry 160, no. 3: 585–587. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , Moulds M. L., Guthrie R. M., et al. 2008. “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Exposure Therapy and Cognitive Restructuring for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, no. 4: 695–703. 10.1037/a0012616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , Moulds M. L., Nixon R. D., Mastrodomenico J., Felmingham K., and Hopwood S.. 2006. “Hypnotherapy and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy of Acute Stress Disorder: A 3‐Year Follow‐Up.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 44, no. 9: 1331–1335. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardeña, E. , Dennis J. M., Winkel M., and Skitka L. J.. 2005. “A Snapshot of Terror: Acute Posttraumatic Responses to the September 11 Attack.” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 6, no. 2: 69–84. 10.1300/J229v06n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M. , Aires Dias J., and Madeira L.. 2023. “Does the Media (Also) Keep the Score? Media‐Based Exposure to the Russian‐Ukrainian War and Mental Health in Portugal.” Journal of Health Psychology 29, no. 13: 1475–1488. 10.1177/13591053231201242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. 2008. “Acute Stress Disorder in Older, Middle‐Aged and Younger Adults in Reaction to the Second Lebanon War.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 23, no. 1: 34–40. 10.1002/gps.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik, J. C. , Sartory G., Nuyken M., Schürholt B., and Seitz R. J.. 2017. “Posterior and Prefrontal Contributions to the Development Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom.” European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 267, no. 6: 495–505. 10.1007/s00406-016-0713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietch, J. R. , Ruggero C. J., Schuler K., Taylor D. J., Luft B. J., and Kotov R.. 2019. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Sleep in the Daily Lives of World Trade Center Responders.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 24, no. 6: 689–702. 10.1037/ocp0000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGrande, L. , Perrin M. A., Thorpe L. E., et al. 2008. “Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, PTSD, and Risk Factors Among Lower Manhattan Residents 2–3 Years After the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 21, no. 3: 264–273. 10.1002/jts.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, D. , Mills M. A., and Park C. L.. 2010. “Factor Structure of the Acute Stress Disorder Scale in a Sample of Hurricane Katrina Evacuees.” Psychological Assessment 22, no. 2: 269–278. 10.1037/a0018506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erçin‐Swearinger, H. , Lindhorst T., Curtis J. R., Starks H., and Doorenbos A. Z.. 2022. “Acute and Posttraumatic Stress in Family Members of Children With a Prolonged Stay in a PICU: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial.” Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 23, no. 4: 306–314. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farchi, M. , and Gidron Y.. 2010. “The Effect of ‘Psychological Inoculation’ Versus Ventilation on the Mental Resilience of Israeli Citizens Under Continuous War Stress.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 198, no. 5: 382–384. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181da4b67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farchi, M. U. , Bathish L., Hayut N., Alexander S., and Gidron Y.. 2024. “Effect of a Psychological First Aid (PFA) Based on the SIX Cs Model on Acute Stress Responses in a Simulated Emergency.” Psychological Trauma. 10.1037/tra0001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feriante, J. , and Sharma N. P.. 2023. Acute and Chronic Mental Health Trauma. StatPearls Publishing. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S. , Ahern J., Resnick H., et al. 2002. “Psychological Sequelae of the September 11 Terrorist Attacks in New York City.” New England Journal of Medicine 346, no. 13: 982–987. 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrion, S. , Goncalves J., Robichaud I., et al. 2022. “Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis on Acute Stress Disorder: Rates Following Different Types of Traumatic Events.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23, no. 1: 213–223. 10.1177/1524838020933844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A. G. , and Bryant R. A.. 1999. “Acute Stress Disorder Across Trauma Populations.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187, no. 7: 443–446. 10.1097/00005053-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, L. , Besser A., and Neria Y.. 2015. “Acute Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms But Not Generalized Anxiety Symptoms Are Associated With Severity of Exposure to War Trauma: A Study of Civilians Under Fire.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 35: 27–34. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppen, T. H. , Priebe S., Vetter I., and Morina N.. 2021. “Global Burden of Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder and Major Depression in Countries Affected by War between 1989 and 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” BMJ Global Health 6, no. 7: e006303–e006316. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassaye, A. , Demilew D., Fanta B., et al. 2023. “Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder and Its Associated Factors Among War‐Affected Residents in Woldia Town, North East Ethiopia, 2002; Community Based Cross‐Sectional Study.” PLoS One 18, no. 12: e0292848. 10.1371/journal.pone.0292848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhi, S. , Eshel Y., Leykin D., and Lahad M.. 2017. “Individual, Community and National Resilience in the Peace‐Time and in Face of Terror: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Loss & Trauma 22, no. 8: 698–713. 10.1080/15325024.2017.1391943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kordel, P. , Rządeczka M., Studenna‐Skrukwa M., Kwiatkowska‐Moskalewicz K., Goncharenko O., and Moskalewicz M.. 2024. “Acute Stress Disorder Among 2022 Ukrainian War Refuges: A Cross‐Sectional Study.” Frontiers in Public Health 12: 1280236. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1280236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. H. , Lee D., Kim J., Jeon K., and Sim M.. 2017. “Duty‐related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Professional Firefighters.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 30, no. 2: 133–141. 10.1002/jts.22180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi‐Belz, Y. , Groweiss Y., Blank C., and Neria Y.. 2024. “PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety After the October 7, 2023 Attack in Israel: A Nationwide Prospective Study.” EClinical Medicine 68: 102418. 10.1016/eclinm.2023.102418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G. C. , Platts‐Mills T. F., Liberzon I., et al. 2014. “Incidence and Predictors of Acute Psychological Distress and Dissociation After Motor Vehicle Collision: A Cross‐Sectional Study.” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 15, no. 5: 527–547. 10.1080/15299732.2014.908805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. , He X., Wang S., Li J., and Zhang Y.. 2021. “Media Exposure Predicts Acute Stress and Probable Acute Stress Disorder During the Early COVID‐19 Outbreak in China.” PeerJ 9: e11407–e11431. 10.7717/peerj.11407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C. P. , and Anderson E. R.. 2009. “Brave Men and Timid Women? A Review of the Gender Differences in Fear and Anxiety.” Clinical Psychology Review 29, no. 6: 496–505. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs . 2024. Israel/Palestinian Territories – Hamas’ Leader in the Gaza Strip, Yahya Sinwar, Listed as a Terrorist by the European Union (16 January 2024). https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country‐files/israel‐palestinian‐territories/news/2024/article/israel‐palestinian‐territories‐hamas‐leader‐in‐the‐gaza‐strip‐yahya‐sinwar.

- Mordeno, I. G. , Gallemit I. M. J. S., Ferolino M. A. L., and Sinday J. V.. 2021. “DSM‐5‐Based ASD Models: Assessing the Latent Structural Relations With Functionality in War‐Exposed Individuals.” Psychiatric Quarterly 92, no. 1: 347–362. 10.1007/s11126-020-09804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria, Y. , Nandi A., and Galea S.. 2008. “Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Disasters: A Systematic Review.” Psychological Medicine 38, no. 4: 467–480. 10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria, Y. , Wickramaratne P., Olfson M., et al. 2013. “Mental and Physical Health Consequences of the September 11, 2001 (9/11) Attacks in Primary Care: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 26, no. 1: 45–55. 10.1002/jts.21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, A. , Hoffman J., Keegan D., et al. 2023. “Intolerance of Uncertainty, Posttraumatic Stress, Depression, and Fears for the Future Among Displaced Refugees.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 94: 1–10. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2023.102672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikopoulou, V. A. , Gliatas I., Blekas A., et al. 2022. “Uncertainty, Stress, and Resilience During the COVID‐19 Pandemic in Greece.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 210, no. 4: 249–256. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North, C. S. , Pollio D. E., Smith R. P., et al. 2011. “Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Employees of New York City Companies Affected by the September 11, 2001 Attacks on the World Trade Center.” Supplement, Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2, no. S2: S205–S213. 10.1001/dmp.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouanes, S. , Bouasker A., and Ghachem R.. 2014. “Psychiatric Disorders Following the Tunisian Revolution.” Journal of Mental Health 23, no. 6: 303–306. 10.3109/09638237.2014.928401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palgi, Y. , Greenblatt‐Kimron L., Hoffman Y., et al. 2024. “PTSD Symptoms and Subjective Traumatic Outlook in the Israel‐Hamas War: Capturing a Broader Picture of Posttraumatic Reactions.” Psychiatry Research 339: 116096. 10.1016/j.psychres.2024.116096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenger, W. E. , Caddell J. M., Ebert L., et al. 2002. “Psychological Reactions to Terrorist Attacks: Findings From the National Study of Americans’ Reactions to September 11.” JAMA 288, no. 5: 581–588. 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrira, A. , and Palgi Y.. 2024. “Age Differences in Acute Stress and PTSD Symptoms During the 2023 Israel‐Hamas War: Preliminary Findings.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 173: 111–114. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, R. , Holman E. A., McIntosh D. N., Poulin M., and Gil‐Rivas V.. 2002. “Nationwide Longitudinal Study of Psychological Responses to September 11.” JAMA 288, no. 10: 1235–1244. 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowan, W. , and Baziliansky S.. 2024. “Acute Stress Symptoms, Intolerance of Uncertainty and Coping Strategies in Reaction to the October 7 War.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 31, no. 3: e3021. 10.1002/cpp.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser, E. , Den Oudsten B. L., Lodder P., Gosens T., and De Vries J.. 2022. “Psychological Risk Factors That Characterize Acute Stress Disorder and Trajectories of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Injury: A Study Using Latent Class Analysis.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 13, no. 1: 1–17. 10.1080/20008198.2021.2006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser, E. , Gosens T., Den Oudsten B. L., and De Vries J.. 2017. “The Course, Prediction, and Treatment of Acute and Posttraumatic Stress in Trauma Patients: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 82, no. 6: 1158–1183. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahav, R. , and Cohen M.. 2007. “Symptoms of Acute Stress in Jewish and Arab Israeli Citizens During the Second Lebanon War.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 42, no. 10: 830–836. 10.1007/s00127-007-0237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z. , Yang X., Zeng C., et al. 2020. “Resilience, Social Support, and Coping as Mediators Between COVID‐19‐Related Stressful Experiences and Acute Stress Disorder Among College Students in China.” Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being 12, no. 4: 1074–1094. 10.1111/aphw.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.