Abstract

Phosphatidic acid (PA) through its unique negatively charged phosphate headgroup binds to various proteins to modulate multiple cellular events. To perform such diverse signaling functions, the ionization and charge of PA's headgroup rely on the properties of vicinal membrane lipids and changes in cellular conditions. Cholesterol has conspicuous effects on lipid properties and membrane dynamics. In eukaryotic cells, its concentration increases along the secretory pathway, reaching its highest levels toward the plasma membrane. Moreover, membrane cholesterol levels are altered in certain diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, cancer, and in erythrocytes of hypercholesteremia patients. Hence, those changing levels of cholesterol could affect PA's charge and alter binding to effector protein. However, no study has investigated the direct impact of cholesterol on the ionization properties of PA. Here, we used 31P MAS NMR to explore the effects of increasing cholesterol concentrations on the chemical shifts and pKa2 of PA. We find that, while the chemical shifts of PA change significantly at high cholesterol concentrations, surprisingly, the pKa2 and charge of PA under these conditions are not modified. Furthermore, using in vitro lipid binding assays we found that higher cholesterol levels increased PA binding of the Spo20p PA sensor. Finally, in cellulo experiments demonstrated that depleting cholesterol from neurosecretory cells halts the recruitment of this sensor upon PA addition. Altogether, these data suggest that the intracellular cholesterol gradient may be an important regulator of proteins binding to PA and that disruption of those levels in certain pathologies may also affect PA binding to its target proteins and subsequent signaling pathways.

Supplementary key words: cholesterol, phosphatidic acid, lipid-protein interactions, Signaling lipids

Graphical Abstract

Cellular environments are dynamic, with significant variations in the concentrations of distinct lipids in different membranes (1). Coupled with changes in cytosol composition, cells have evolved to take advantage of the unique properties and structure of membrane lipids to accompany various cellular functions (2, 3). Therefore, investigating the behavior of lipids, particularly those involved in signaling, in physiologically relevant cytoplasmic conditions, is vital to understanding their properties upon interaction with different membrane molecules. Such investigations provide fundamental insights into the nature of signaling lipids (4, 5). They also explain their behavior in different membrane environments and cellular conditions, especially when the relative abundance of membrane lipids is modified in pathological development.

Phosphatidic acid (PA) is an anionic cone-shaped lipid mostly present in minute quantities in yeast (6) and mammalian cell membranes (7, 8). Despite its low abundance, it is highly influential in modulating membrane structure and function. PA is involved in lipid and membrane biogenesis at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (9). However, it also plays central roles in other membrane compartments such as the Golgi apparatus, vesicular, mitochondrial, and plasma membranes (PM). For instance, PA mediates vesicular trafficking from the ER to the Golgi, and its synthesis is required to maintain the normal structure and function of the Golgi apparatus (10, 11). In neurosecretory cells, PA has been shown to contribute to secretory vesicle biogenesis (12) and their subsequent transport, docking, and fusion to the plasma membrane (13, 14, 15). In yeast cells, PA is required at the ER for regulating lipid metabolism through its interaction with Opi1 (2). It has also been implicated in thrombogenic activity in red blood cells (16).

Hence, over the last few years, this unique phospholipid has emerged as a crucial signaling molecule in all eukaryotic cells. To promote specific signaling pathways, PA’s negatively charged phosphomonoester headgroup can bind specific cationic domains of proteins and mediate downstream responses (17). PA-protein binding is influenced by the chemical properties of vicinal membrane molecules and the cytosolic environment (4). For example, changes in cytosolic pH and hydrogen bonding lipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) affect the ionization properties of PA (18). Additionally, the relative abundance of PE can affect PA’s charge (4). These complex interactions, together with lipid packing defects (curvature stress of the membrane) can influence the ability of proteins to bind PA (17).

Among all factors influencing lipid and membrane properties, cholesterol has emerged as a crucial mediator of protein-lipid interactions in cellular bilayers. For instance, cholesterol enhanced the binding of the retroviral GAG protein to the bilayer (19). This increased binding has been proposed to result from a higher charge density of the bilayer, therefore, promoting electrostatic interactions with the protein. Additionally, cholesterol decreases the energy requirement to remove water from the headgroup of lipids, thus favoring protein binding (19). Finally, cholesterol can also directly affect the binding of proteins to membranes by modulating their stability and conformational equilibria (20, 21, 22).

Cholesterol is made of a single hydroxyl and a short acyl chain at either end of a fused planar 4-ringed structure. This rigid structure enables cholesterol to modulate membrane properties such as surface area, fluidity, and permeability (23, 24). In its absence, membrane bilayers either adopt a gel or liquid crystalline state at lower and higher temperatures respectively (25). Increasing cholesterol concentrations in lipid bilayers change their properties and they adopt a liquid-ordered phase, an intermediate between the gel and liquid crystalline states (25, 26). Cholesterol distinctly affects lipid properties based on the chemical characteristics of neighboring lipids. On the one hand, its affinity with sphingolipids and phospholipids varies based on structural differences in the backbone of the two lipids (25, 27). On the other hand, cholesterol also affects the ordering of lipid acyl chains in both the gel and the liquid crystalline states (23). In phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylserine bilayers, cholesterol was shown to decrease the average area occupied by a single lipid and increase bilayer thickness (19, 28).

Additionally, the relative abundance of cholesterol varies significantly in different organelle membranes. Its concentration increases along the secretory pathway from the ER to the PM (20, 29). In the ER, cholesterol has a relative concentration of about 5% of the total lipids (29), whereas its concentration in the PM is estimated at 30% (30, 31). The PM distribution in mammalian cells is highly asymmetric, depends significantly on cell type, and is modulated in a stimulus-specific manner (32, 33, 34, 35). The cholesterol concentrations in intermediate compartments such as the Golgi range between that of the ER and the PM. Furthermore, certain pathological conditions can induce a change in intracellular cholesterol levels. Membranes of sickle cell disease patients have lower cholesterol concentrations (36). Cholesterol levels are increased in the erythrocytes of patients with hypercholesteremia (37). Several studies suggest a link between high cholesterol concentrations and Alzheimer's disease (AD) (38, 39). There are also reports of reduced cholesterol levels in the neurons of AD patients (40). In both instances, changes in cholesterol levels seem to play a role in AD pathogenesis.

PA and cholesterol have synergistic effects on membrane structure and function. They are both required for the transport of glycoproteins and membrane proteins from the ER to the Golgi (10, 41). In addition, increasing levels of either PA and/or cholesterol affects the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (42, 43). In AD, the changes in cellular cholesterol content have also been reported to be accompanied by modifications in PA levels (44). In vitro studies confirmed a high affinity between bilayers containing PA and the amyloid beta (Aβ) protein (45). The formation of pathogenic Aβ fibrils has been reported to be favored through interactions with anionic lipids such as PA (46). Cholesterol levels have also been reported to significantly affect the interaction of Aβ peptide with membranes (47). In this instance, cholesterol could alter the ionization properties of PA to affect its binding to Aβ fibrils or act via an alternate mechanism. Differences in cholesterol concentration across the membranes of the ER to the PM could also affect PA's charge, protein binding and its signaling functions in these organelles by recruiting different effectors.

We previously investigated PA’s ionization properties upon interaction with cholesterol and PE (4). While the two lipids share similarities such as inducing very close negative spontaneous curvatures (48), they also vary in terms of their structural rigidity (cholesterol being more rigid), and effects on membrane bending and fluidity. PE’s primary amine headgroup can form hydrogen bonds with other lipid headgroups (phosphates) to affect the charge of the lipid (4, 18, 49). However, it remains unclear whether cholesterol exerts similar effects by interacting with other anionic lipids. PE’s hydrogen bonding ability could have masked the effects of cholesterol in this model system (4). No investigations have therefore been done, to the best of our knowledge, on how increasing cholesterol concentrations affects the ionization properties of PA. In this study, we used 31P MAS NMR to determine the physicochemical properties of PA in model membranes with increasing cholesterol concentrations. Our results show that increasing its level significantly affects the chemical shifts of PA in PC bilayers. Therefore, cholesterol might act as a spacer for PA in accordance with previous work on the impact of cholesterol on anionic lipids (50). Additionally, higher cholesterol (30%) does not significantly alter the pKa2 and charge of PA in PC bilayers but favors the interaction with the yeast PA-binding protein Spo20p in liposome binding assays. Moreover, manipulating cholesterol levels in bovine chromaffin cells also impacted GFP-Spo20p recruitment to the periphery of the cells upon PA addition demonstrating the importance of this PA-cholesterol interaction for protein binding in a cellular environment.

Materials and Methods

Liposome preparation

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DOPA), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (PE-NBD) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cholesterol was either purchased from Nu-Chek Prep Inc, or from Avanti Polar Lipids.

All lipids were individually dissolved in a mixture of 2:1 ratio of chloroform and methanol. Phospholipid purity was checked on a thin layer chromatography (TLC) plate using a 65/25/4 chloroform/methanol/water solvent. Only lipid stocks that showed a single spot on the TLC were used for the experiments.

NMR sample preparation

The lipid samples used for NMR experiments were made as previously described (51). We prepared 10 μmol total lipid films in a borosilicate glass tube by mixing calculated amounts of lipids from stock solutions. For the physiological pH (7.2) experiments, lipids made were of the ratio (i) 90 mol % DOPC and 10 mol % DOPA (control), (ii) 80 mol % DOPC, 10 mol % cholesterol and 10 mol % DOPA, (iii) 70 mol % DOPC, 20 mol % cholesterol and 10 mol % DOPA and (iv) 60 mol % DOPC and 30 mol % cholesterol and 10 mol % DOPA. 6 sets of lipid films were made for each of these lipid sets. 15 lipid films were made for the lipid set 60 mol % DOPC 30 mol % cholesterol and 10 mol % DOPA used to determine the ionization constant. Lipid films were evaporated and dried under nitrogen gas as previously described (4).

50 mM of the following buffers were used to hydrate the lipid films; 20 mM citric acid, 30 mM MES for pH 4–6.5, 50 mM HEPES for pH 6.5–8.5, and 50 mM glycine for pH 8.5–11. All buffers also contained 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM EDTA. 100 mM HEPES buffer was used for pH 7.2 ± 0.05 experiments to minimize pH variation. The lipid films were thoroughly vortexed after hydration to ensure complete dispersion of lipids in the buffer. Hydrated lipid films were frozen in a mixture of dry ice and ethanol. They were then thawed in warm water with intermittent vortexing. The hydrated lipids were frozen and thawed twice to form multi-lamellar vesicle (MLV) dispersions. The final bulk pH at room temperature was measured with a standard pH meter and an Intelli pH probe (Sentron). The pH values obtained were used to make the pH-titration curve. Lipid samples were spun down at 15,000 RPM at 4°C for 50 min to concentrate wet lipids into a pellet. The lipid pellets were transferred with a glass pipette into 4-mm zirconium MAS NMR sample tubes.

31P NMR spectra were recorded using a 400 mHz Bruker spectrometer as previously described (51). The chemical shifts of lipids were acquired by spinning samples at 5 kHz at 21 ± 1.0°C and at the magic angle of 54.7°. The positions of lipid peaks were referenced by using an external 85% H3PO4 standard. Approximately, 15,000–20,000 scans were recorded for each of the lipid samples. We determined only the second ionization constant (pKa2) that is the upper part of the full titration curve of our lipid systems as we have previously shown that this does not significantly affect the pKa2 of the ionization behavior that is determined at the physiological pH range (4, 52). A low-power proton decoupling was used to confirm the phase behavior for all lipid samples after each MAS spectra was recorded. 50,000 to 70,000 scans were recorded for each static spectrum.

Determination of pKa2 values from titration curves and determination of headgroup charge

The pKa2 value of DOPA’s phosphomonoester was determined by using a Henderson-Hasselbalch equation and a nonlinear least squares fit procedure. The pKa2 was determined by fitting the data over the pH range 4–11 by using a modified equation (4, 52).

| (1) |

where δ is the measured pH-dependent chemical shift, δA is the chemical shift of the singly dissociated state, δB is the chemical shift of the doubly dissociated state, pH is the log of the measured hydrogen concentration, and pKa is the second dissociation constant of the respective phosphomonoester.

The degree of protonation, as a function of pH was calculated from Equation 2 based on the assumption that the CS values are the weighted averages between the singly and doubly deprotonated states of the phosphomonoester groups.

| (2) |

where is the pH-dependent CS of the phosphomonoester group, and are the CS values of the singly and fully deprotonated phosphomonoester groups, respectively (53).

Expression of recombinant GST-Spo20p proteins

Amino acids 50–101 from Spo20p (GenBank DAA09915.1) were used as PA binding domain. The latter was amplified by PCR from the pEGFP-C1-Spo20p construct (54) using the forward primer 5′CGGGATCCCTCGAG CGTCTAGAATGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCGAATTCTTAACTAGTCTTAGTG GCGTC-3′ (54, 55) and inserted in frame into pGEX4T1 as previously described (54). The sequence was verified by automated sequencing. Large-scale production of recombinant GST-Spo20p has been previously described (55). Briefly, expression was induced at 37°C, and fusion proteins were purified on glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose, and purity was estimated to be >95% by Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE gels (56). The amount of purified protein was determined using a dye-binding assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Liposome binding assay

Lipids solubilized in chloroform were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Liposome mixtures were prepared in mass ratios composed of 85% DOPC, 5% NBD-labeled phosphatidyl ethanolamine, and 10% DOPA with increasing amounts of cholesterol at the expense of DOPC. Lipids were dried in a stream of nitrogen gas and kept under a vacuum overnight. Dried lipids were then suspended at a concentration of 1.65 mg/ml in liposome-binding buffer (LBB; 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2) and were extruded using a Mini-Extruder (Avanti) through polycarbonate track-etched membrane filters to produce 200 nm diameter liposomes. The size distribution of liposomes was estimated by dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer NanoS from Malvern Instruments equipped with a 4 mW laser.

GST-Spo20p (330 pmol) bound to GSH beads were washed once with 1 ml LBB before incubation for 20 min in the dark at room temperature and under agitation with liposomes containing a 10-fold molar excess of PA relative to the quantity of GST-proteins and varying cholesterol concentration (from 0% to 50%) in a final volume of 200 μl LBB. Beads were washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold LBB buffer and collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. Liposome binding to the GST-Spo20p was estimated by measuring the fluorescence at 535 nm with a Mithras (Berthold) Fluorimeter. Triplicate measurements were performed for each condition. Fluorescence measured with GST linked to GSH-sepharose-beads alone was subtracted from sample measurements.

Primary bovine chromaffin cell culture

We used chromaffin cells from the adrenal medulla gland as these were the first models in which PA synthesis at the plasma membrane during exocytosis was revealed using the PA sensor GFP-Spo20p (54). Bovine adrenal glands were obtained at the Haguenau municipal slaughterhouse and placed in a 4°C calcium-free Krebs solution (NaCl 154 mM, KCl 5.6 mM, NaHCO3 3.6 mM, glucose 5.6 mM and HEPES 5 mM, pH adjusted to 7.4) supplemented with the broad-spectrum antibiotic, primocine at 100 μg/ml and adrenal medulla cells were cultured as described previously (57). Glands were digested twice for 10 min at 37°C with a collagenase A solution (Collagenase A 3.5 mg/ml, BSA 5 mg/ml, resuspended in Krebs solution). The adrenal medulla was separated from the cortex and minced and digested for 5 min with the remaining collagenase A solution. Bovine chromaffin cells were passed through a 217 μm sieve, centrifuged for 10 min at 130 g resuspended in Krebs solution, and passed through a 70 μm sieve. Bovine chromaffin cells were isolated with a Percoll density gradient generated with a 20 min centrifugation at 20,000 g. Cells were resuspended in culture medium (low glucose DMEM supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), centrifuged at 130 g for 10 min, resuspended, and counted.

PA sensor recruitment

Bovine chromaffin cells were transfected directly after the culture as described previously (58). 8,000,000 cells were resuspended in an antimitotic, antibiotic-free medium (low glucose DMEM supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine and 10% FBS) and mixed with a plasmid encoding for the Spo20p-GFP PA sensor. Nucleofection was performed by using the basic primary neuron nucleofector kit (Lonza©) and cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips. 5 h after this procedure, antimitotics and antibiotics were added to the medium (10 μM fluorodesoxyuridine, 10 μM cytosine arabinoside, 100 μg/ml primocine). The following day, medium of the cells was changed. Cholesterol depletion was performed by incubating cells with a methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) enriched Locke’s solution (140 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 11 mM glucose, 570 μM ascorbic acid, 10 μM EDTA, 15 mM HEPES and 10 mM MβCD, pH adjusted to 7.5) for 30 min. Afterwards, cells were washed twice with Locke’s solution and 100 μM of egg PA mixture was added to the cells for 15 min when indicated. Cells were fixed with a 10 min incubation of 4% PFA-PBS solution, nuclei and cortical actin were stained using Hoechst 33,342 and phalloidin-Atto-647N, and coverslips were mounted using Mowiol 4–88 mounting medium as described previously (59).

Images were obtained using a SP5II confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica©) with a 63× oil immersion objective. The acquisition was performed via the LAS AF software in a sequential scanning mode with a pinhole opening of 1 airy unit. Three channels were imaged separately, the resolution was set at 512×512 pixels with a scanning speed of 400 Hz, a bit rate of 16, no smart offset, a zoom of 6 and a line average of 4. Hoechst 33,342 (Nuclear stanning) was stimulated with a 405 nm emitting laser. GFP (PA sensor: Spo20p-GFP) was stimulated with a 490 nm emitting argon laser. Atto647N (Cortical actin) was stimulated with a 633 nm emitting helium/neon laser. 15 isolated cells were acquired per condition and experiment, all images were taken with the same settings and saved as LIF files. After acquisition images were converted from LIF files into TIF files by using the standard Bioformat plugin on the FIJI software. Segmentation of the peripheral area was performed on the ICY software by using the active contour plug-in. Hoechst staining was used for nuclei segmentation and cortical actin staining for peripheral segmentation. This enabled us to quantify the total, peripheral, and nuclear area of the imaged cell along with the GFP intensity in each of those areas. Spo20p recruitment was evaluated by dividing the mean peripheral GFP signal by the mean nuclei GFP signal for each cell (13).

Statistical analysis

The number of experiments and repeats are indicated in figure legends. For NMR experiments, SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc) was used to plot graphs by using the means and SD. In addition, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test was used to determine significance. In vitro and in cellulo assays statistics and graphs were realized on the graphpad® prism 8 software by performing a Kruskall-Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

Results

Cholesterol has a significant influence on membrane properties and on the structure and function of lipids (23, 60, 61). Cholesterol has negative spontaneous curvature like PE, but the major difference between the two in terms of their interactions with lipids is that the PE headgroup is favorably positioned in the membrane interface to form hydrogen bonds with the headgroups of signaling lipids such as PA, diacylglycerol pyrophosphate (DGPP) and with phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) (4, 49, 62). Cholesterol, on the other hand, has not yet been demontrated to form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate headgroups of neighboring lipids. This is due to the location of cholesterol being closer to the acyl chain region of the lipid bilayer (25, 27, 63). Cholesterol concentrations vary in different membrane compartments and can also be modified in certain diseases such as AD. In the PM the majority of cholesterol has been suggested to reside in the exoplasmic leaflet (31, 64, 65). These changes in cholesterol content could affect the physicochemical properties of PA depending on the cellular compartment it is located in as it does for PI(4,5)P2 where cholesterol induces domain formation (50, 66, 67). Cholesterol could alter PA's charge, interaction with membrane proteins, and therefore control the ensuing signaling cascade. Kooijman et al. incorporated cholesterol in mixed lipid bilayers (PC/PE/PA) and observed a change in chemical shift induced by cholesterol (4). This shift was interpreted as cholesterol increasing the charge of PA. However, this work was complicated by the fact that the mixtures contained PE, and no full titration curves were generated to unequivocally show the effect of cholesterol on PA ionization properties. Interestingly, the work on PI(4,5)P2 also only relied on chemical shift changes of PA-induced by cholesterol to extract effects on PA’s charge (50). In this study, we use 31P MAS NMR to systematically determine the effects of increasing cholesterol concentrations on the chemical shift and, most importantly, the ionization properties of PA in PC bilayers. In addition, using in vitro and in cellulo assays, we show that changes in cholesterol levels significantly modulate protein binding to PA by working with the stereotypical PA binding protein: Spo20p.

PA is an anionic lipid with a phosphomonoester headgroup that lies closer to the acyl chain region of the bilayer than any other anionic lipid headgroup (68). Its charge and pKa2 can be modified based on the properties of vicinal lipids as observed when it hydrogen bonds with PE (4, 69). Cholesterol could modulate the ionization properties and charge of PA in a concentration-dependent manner by acting as a spacer in the membrane, thereby decreasing the surface charge density of the membrane. A reduced surface charge density would result in a higher surface pH (lower H+ concentration), and thus a higher PA charge compared to the system without cholesterol. As in the case of PE, cholesterol could potentially form hydrogen bonds with the PA headgroup based on the location of its phosphomonoester and cholesterol’s OH group in the membrane interface (4). Both would ultimately affect PA's charge, interaction with membrane proteins, and downstream signaling functions.

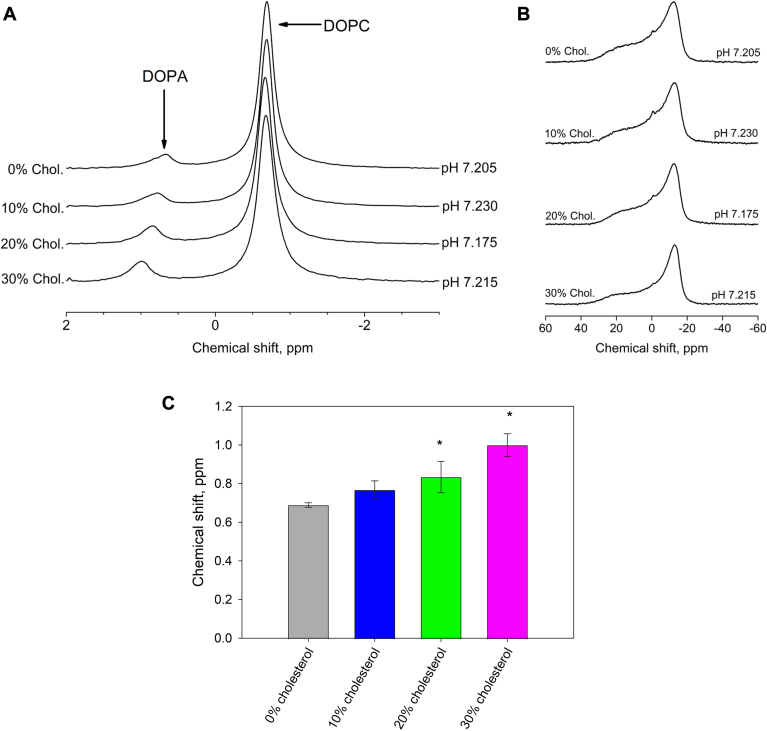

To determine the effects of varying cholesterol concentrations on the phosphomonoester of DOPA, we first determined the chemical shifts of 10 mol % DOPA in increasing cholesterol concentrations (10, 20, and 30 mol %) and corresponding decreasing DOPC concentrations at physiological pH (7.20 ± 0.05). DOPC was used because it forms fluid bilayers at room temperature, does not form hydrogen bonds with lipids, and has also been used as the model membrane matrix lipid in previous works (4). Six samples were made at each cholesterol concentration to determine the 31P chemical shifts of DOPA (and DOPC). As a control, we determined the chemical shift values of 6 different samples of 10 mol % DOPA in pure DOPC bilayers. We show one representative 31P MAS NMR spectra for each of the lipid mixtures in Fig. 1A. The peak positions for DOPA and DOPC are resolved based on their locations from previous studies and the relative concentrations of the two lipids in samples (4). Their corresponding static spectra are also shown in Fig. 1B. The low field shoulder and high field peak of all static spectra demonstrated that the samples formed bilayers even at high cholesterol concentrations (70). A small amount of isotropic signal was detected in all samples which is usual for MLVs formed by vortexing and freeze/thaw of the samples.

Fig. 1.

A: 31P MAS NMR spectra showing the stacked chemical shifts of 10% DOPA in x % cholesterol and (90-x) % DOPC at pH values of 7.2 ± 0.05. B: The corresponding static NMR spectra from Figure 1A samples. C: Bar graph showing the averaged chemical shift values of DOPA's phosphomonoester peaks in increasing cholesterol concentrations. Chemical shift values are obtained from 31P MAS NMR spectra of 10% DOPA, x% cholesterol, and (90-x) % DOPC multi-lamellar vesicles in buffer at pH 7.2 ± 0.5. Error bars show the standard deviation measured from six samples. ∗P < 0.001.

The averaged values of the peak positions of DOPA (and DOPC) in the increasing cholesterol concentrations at pH 7.2 are shown in Table 1. The corresponding bar graphs for DOPA are shown in Fig. 1C. From Table 1, there are very minor increments in the DOPC peak positions as cholesterol concentrations are increased but this is not noticeable in the stacked plots in Fig. 1A. However, there is a more prominent cholesterol concentration-dependent downfield movement in the peak positions of DOPA in both Fig. 1A and Table 1 in line with previous work (4). One-way ANOVA and Dunnett's test performed on the DOPA data showed significant differences between 20 and 30 mol % cholesterol-containing samples and the control. In the past, we have interpreted downfield shifts in the DOPA peak positions as changes in the electrostatics around DOPA and an increase in PA charge (4). However, is this indeed the case?

Table 1.

Chemical shift values and pKa2 of 10% DOPA in increasing cholesterol concentrations

| Lipid Composition | Averaged chemical Shift of DOPC at pH 7.2 | Averaged chemical Shift of DOPA at pH 7.2 | pKa2 of DOPA | Charge of DOPA at pH 7.20 (±0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% DOPA 90% DOPC | −0.69 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 7.92 ± 0.03 (4) | 1.16 (4) |

| 10% DOPA 10% Cholesterol 80% DOPC | −0.68 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | _ | _ |

| 10% DOPA 20% Cholesterol 70% DOPC | −0.67 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | _ | _ |

| 10% DOPA 30% Cholesterol 60% DOPC | −0.67 ± 0.02 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 7.87 ± 0.04 | 1.20 |

Downfield shifts of the 31P NMR peak indicate changes in the shielding of the phosphorus nucleus. Changes in shielding could originate from other processes than deprotonation of the phosphate headgroup. Higher concentrations of cholesterol could alter the chemical shift of DOPA by acting as spacers between membrane lipids as has been proposed for the interaction of cholesterol with PI(4,5)P2 (50). In this study the increased spacing was proposed to increase the charge of the 4- and 5-phosphate of PI(4,5)P2 due to a decreased surface charge density. Hydrogen bonding of the -OH of cholesterol with these phosphates is not plausible due to their location in the membrane interface. Alternately, cholesterol could form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate headgroup of PA but this has not yet been observed in cholesterol's interactions with anionic lipid headgroups. To shed light on the role of cholesterol in the ionization properties of PA we determined the pH-dependent chemical shift of DOPA in a model DOPC membrane containing 30 mol % cholesterol. We chose this concentration of cholesterol as it is close to the PM cholesterol concentration, and since we observed the largest change in the chemical shift of PA.

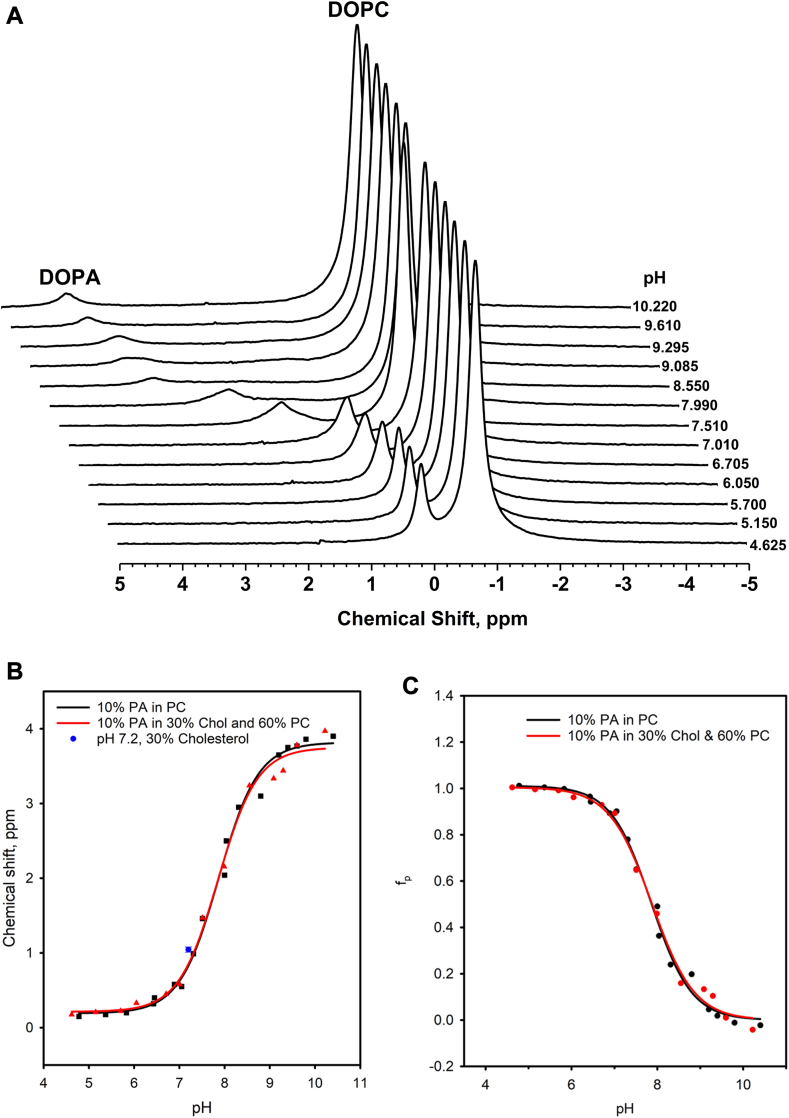

The waterfall plot for 10 mol % DOPA in 30 mol % cholesterol and 60 mol % DOPC, determined over a pH range from 4 to 11, is shown in Fig. 2A. The corresponding static spectra indicate that all samples formed bilayers irrespective of pH (data not shown). The pH-chemical shift from Fig. 2A is plotted together with control data (taken from Kooijman et al. (4)) in Fig. 2B. This graph also contains the averaged chemical shift value for 10 mol % DOPA in 30 mol % cholesterol measured at a constant pH of 7.20 ± 0.05 from Fig. 1C, and Table 1. This data point was not taken into account when calculating the pKa2 of cholesterol as the buffer conditions are different to assure a constant pH. However, when we do add this data point to the pH-titration curve data and determine the pKa2 again there is no significant change in the value. The degree of protonation calculated using Equation 2 as a function of pH for the control and the 30 mol % sample are plotted in Fig. 2C. This data was used to determine the respective charges at pH 7.2 shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

A: 31P MAS NMR spectra as a function of pH for 10 mol % DOPA in 60 mol % DOPC and 30 mol % cholesterol vesicles. B: The titration curve for 10% PA in 30 mol % cholesterol and 60 mol % DOPC (red triangles and lines) is compared against the control curve (black squares and lines). The averaged chemical shift for 10 mol % PA in 30 mol % cholesterol (blue square) is plotted in the graph. The solid lines represent a Henderson–Hasselbalch fit of the ionization data (see Materials and Methods). C: Degree of protonation (fp) as a function of pH for 10 mol % DOPA in 30 mol % cholesterol and 60 mol % DOPC plotted in the control.

Surprisingly, 30 mol % cholesterol does not affect the pH titration curve for PA significantly. Indeed, this curve essentially overlaps with the control (0% cholesterol) titration curve. The same is true for the protonation curve shown in Fig. 2C. This is unexpected since the PA chemical shift at 30 mol % cholesterol determined at physiological pH (7.20 ± 0.05) is significantly different from the chemical shift for the control (i.e. 0% cholesterol), see Fig. 1. This significant change in chemical shift to downfield values suggests deprotonation of the PA headgroup. However, the pKa2 and charges determined (at pH 7.2) for PA in 30 mol % cholesterol and the control are similar (values shown in Table 1). This observation thus rules out a possible hydrogen bond interaction between the hydroxyl of cholesterol and the phosphomonoester headgroup of PA.

The effect of 20 mol % cholesterol on PA was previously examined while also changing the concentrations of PE in a PC model bilayer at constant pH (4). The measured chemical shift positions of PA-induced by cholesterol varied based on the percentage of PE in the model membrane and followed the downfield trend we observe here. A larger PE concentration masked much of the downfield shift induced by cholesterol in this study. These shifts to downfield chemical shift values were interpreted as an increase in PA’s charge and were based on the assumption that any change in the chemical shift position of the PA peak corresponds to a change in charge. Our investigations here show that changes in chemical shift induced by an increase in cholesterol concentration do not correspond to significant changes in PA's pKa2 or its charge unlike previously reported (4). How can these two observations be reconciled?

Molecular dynamics simulations by Yesylevskyy and Demchenko showed a preferential interaction of cholesterol with anionic lipids (over zwitterionic lipids) in asymmetric bilayers (71). They explained this preferential interaction by reduced electrostatic repulsion of charged headgroups induced by cholesterol (which would be energetically more favorable). Additionally, it is likely that this spacing by cholesterol also leads to differences in headgroup hydration, and different water properties at the interface (71). Something not easily accessible by those simulations. Similarly, cholesterol has been proposed to spread out the charge of PI(4,5)P2 by inducing domain formation of this highly charged lipid (50). In our experimental model membranes, cholesterol may act similarly by acting as a spacer between adjacent PA molecules and thereby decreasing the headgroup packing density, leading to reduced chemical shielding of the phosphomonoester headgroup (i.e. deshielding of the phosphorus nucleus) causing a cholesterol dependent downfield shift in the PA peak. Such spacing effects induced by cholesterol on DOPA would also cause less compact packing of PA and the occupied surface area per molecule. This would subsequently induce a reduction of the local charge density around the PA headgroup. The resulting effect reduces the negative membrane potential, increases interfacial pH, and thus increases the charge of PA, explaining the measured change in chemical shift. However, this does not seem to impact the charge of PA (see Fig. 2) and this may be caused by changes in membrane hydration and water structure in the headgroup region. Additionally, the interaction of cholesterol within the membrane may also lead to changes in the orientation of PC headgroups which, combined with differences in hydration and water structure could lead to significant differences in membrane electrostatics (dielectric constant, e.g.) countering the effect of a slightly reduced membrane surface charge density. It should also be noted that in our model membrane systems changes in PA concentration do not lead to significant changes (decreases) in the pKa2 of the PA headgroup (data not shown). This suggests that PA may form small nanoclusters in these model PC membranes. Unpublished work from our group shows that pyrene labeled PA (labeled on one hydrocarbon chain) already exhibits excimer fluorescence without the addition of any additional domain forming actor such as Ca2+, supporting the notion that PA forms small clusters within membranes. Interestingly, addition of PE to these systems does lead to a change in pKa2 when PA concentration is increased suggesting that PE acts to break up these small PA clusters (data not shown).

Next, to probe whether this PA/cholesterol interaction could impact the signaling properties of PA, we determined the effect of increasing cholesterol levels in membranes on the binding of proteins to PA. For this, we used the Spo20p peptide, the yeast homolog of SNAP25, a well-known PA interactant (54), and checked if this interaction is dependent on membrane cholesterol concentrations. Using a fluorescent liposome binding assay, we found that increasing cholesterol led to a gradual increase in PA binding to GST-Spo20p with a peak near 40%–50% of cholesterol in DOPC membranes (Fig. 3), supporting the notion that PA binding to Spo20p was favored at PM cholesterol level. Interestingly, the increase in PA binding starts at around 15 mol % cholesterol, close to the concentrations where we observe a significant change in the chemical shift for PA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Effect of cholesterol on PA binding of Spo20p to liposomes. GST-Spo20p bound to GSH beads were incubated with liposomes containing 5% NBD-PE, 85% of DOPC, and 10% PA (18:0-18:1). The % cholesterol represents the % that replaces DOPC in liposomes. Data are presented as means ± SD obtained in five independent experiments each performed in triplicate measurements. A.U. stands for Arbitrary Units.

We next wanted to validate those observations directly within cells. For this, we expressed the GFP-Spo20p sensor as a stereotypical PA binding protein at the PM of cells. Indeed, in the neuroendocrine secretory bovine chromaffin cells, upon expression, GFP-Spo20p mostly accumulates in the nucleus in an unstimulated condition in agreement with low PA levels measured in this membrane compartment (13). However, this PA sensor is recruited to the cell’s periphery upon stimulation and PLD1-induced PA production, leading to a more than 10-fold PA level increase at the PM (13). Interestingly, it has also been reported that the provision of extracellular PA into the culture media, rapidly reached the inner leaflet of the PM as evidenced by the recruitment of Spo20p after a few minutes of PA treatment (13). Here, we found that cholesterol depletion in bovine chromaffin cells overexpressing Spo20p-GFP did not induce any significant change in the PA sensor’s recruitment without PA addition to the cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Reducing cholesterol levels impaired PA sensor recruitment in bovine chromaffin cells. A: Confocal images of bovine chromaffin cells overexpressing Spo20p-GFP treated with 10 mM MβCD for 30 min or untreated. 100 μM egg PA mixture was added to the cell medium for 15 min when indicated. Each channel is shown individually as a grayscale image, segmented nuclei (Blue), segmented peripheral area (Magenta), and merged (Blue: nucleus, green: spo20p-GFP, and red: actin). Scale bar: 5 μm. B: Spo20p-GFP recruitment quantification. Data are represented as mean peripheral GFP intensity divided by mean nuclear GFP intensity. The black line represents the median and each point is a measure from an individual cell, points are colored red, blue or green according to experimental repeats. n.s: nonsignificant, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, Kruskall-Wallis followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test versus control (45 per condition, 15 cells from 3 independent cultures).

However, as reported previously, we observed that upon a 15 min incubation with an egg PA mixture, a significant increase of GFP-Spo20p recruitment at the PM is observed, indicated by an increase of the Spo20p peripheral over nuclear staining (Fig. 4). Cholesterol depletion with the cholesterol chelator MβCD prior to PA addition completely halted recruitment of GFP-Spo20p to the cell periphery upon PA addition. Previous work, investigating the contribution of cholesterol in regulated exocytosis, indicated that treatment of chromatin cells with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin reduced by 30%–40% the cholesterol membrane content (72). Similar results were obtained in sea urchin eggs (73). Additionally, we observed no significant differences in total cellular areas, nuclear and peripheral proportion and under the conditions tested, indicating that the various treatments did not significantly affect cell shape and size, which could otherwise have induced a bias in the analysis (Supplemental Fig. S1). These data suggest that for binding of Spo20p to PA at the PM, optimal cholesterol levels need to be preserved. For example, in our model membrane systems Spo20p binding increases near 20 mol % cholesterol. This coincides with the threshold concentration of PE which we previously showed for PA-proteins to efficiently bind to PA in model membranes (17). In line with these findings, it is of note that among the different PA sensors reported to date, Spo20p has been reported to bind PA at the PM (74, 75), whereas other sensors such as Opi1p bind PA in the ER or PDE4A1 which is specific to Golgi PA (55, 76, 77). These specificities could therefore be induced by intrinsic differences in cholesterol concentrations within membrane compartments, thereby enabling a recruitment of specific interactants to dedicated intracellular membrane compartments.

Discussion

Our results show an interesting effect of cholesterol concentration on PA’s ionization and protein binding properties. While the chemical shifts of PA are affected by higher cholesterol concentrations, the resulting changes in chemical shift do not translate to changes in PA’s pKa2 and charge. This observation points to a remodeling effect of cholesterol on the membrane which affects PA’s behavior. Cholesterol has been proposed to affect the accessibility of proteins to the lipid headgroups (78). Interestingly, changes in membrane cholesterol concentration affected the binding of a known PA-binding protein, Spo20p, in a concentration-dependent manner. The effect of cholesterol on PA spacing in the membrane may additionally depend on the component fatty acid species (79). We previously showed that PA sensor binding depends on the acyl chain length and saturation of PA species (55). Altering cholesterol levels of neurosecretory cells modified the recruitment of Spo20p to the PM upon PA addition. We previously showed that PA-binding proteins likely require a threshold negative curvature stress to efficiently bind to PA. Our observation here that cholesterol acts as a specific spacer for PA, while not changing its overall charge in the membrane, suggests that cholesterol may have an important modulating effect on protein binding to PA. Altogether the interaction of PA and cholesterol in cellular membranes might therefore potentially explain how PA interactants are recruited to specific organelles with a defined cholesterol concentration. Thereby, offering an original mechanism to confer identity to specific membrane compartments. This mechanism could especially be relevant in pathological conditions where intracellular cholesterol levels might be altered and might thus provide original therapeutic perspectives.

Data availability

All data are included in the current submission and in the supplementary data section. Primary data sets supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental data

This article contains supplemental data.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgment

DOK and EEK would like to thank the Department of Biological Sciences at Kent State University for financial support and Mahinda Gangoda for technical assistance with the solid state NMR work.

Author contributions

E. E. K., N. V., A. W., and D. O. K. writing–review & editing; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. writing–original draft; E. E. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. visualization; E. E. K., N. V., A. W., and D. O. K. validation; E. E. K., N. V., A. W., and D. O. K. supervision; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. software; E. E. K. and N. V. resources; E. E. K., N. V., A. W., and D. O. K. project administration; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. methodology; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. investigation; E. E. K. and N. V. funding acquisition; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. formal analysis; E. E. K., N. K., N. V., A. W., M. L., and D. O. K. data curation; E. E. K. and N. V. conceptualization.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by a grant from “Agence Nationale pour la Recherche” (ANR-19-CE44-0019) to N. V. We acknowledge the In Vitro Imaging Platform - NeuroPôle - Strasbourg (UAR3156), member of the national infrastructure France-BioImaging supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-INBS-04) and the municipal slaughterhouse of Haguenau (France) for providing the bovine adrenal glands. INSERM provided salary to N. V. and the “Fondation pour la recherche médicale” provided salary to A. W. (FDT202304016618).

Contributor Information

Nicolas Vitale, Email: vitalen@inci-cnrs.unistra.fr.

Edgar Eduard Kooijman, Email: ekooijma@kent.edu.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin J.J., Loewen C.J. Putting the pH into phosphatidic acid signaling. BMC Biol. 2011;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin J.J.H., Liu P., Chan L.J., Ullah A., Pan J., Borchers C.H., et al. pH biosensing by PI4P regulates cargo sorting at the TGN. Dev. Cell. 2020;52:461–476e4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kooijman E.E., Carter K.M., van Laar E.G., Chupin V., Burger K.N., de Kruijff B. What makes the bioactive lipids phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid so special? Biochemistry. 2005;44:17007–17015. doi: 10.1021/bi0518794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owusu Kwarteng D., Putta P., Kooijman E.E. Ionization properties of monophosphoinositides in mixed model membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2021;1863 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2021.183692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganesan S., Shabits B.N., Zaremberg V. Tracking diacylglycerol and phosphatidic acid pools in budding yeast. Lipid Insights. 2015;8(Suppl 1):75–85. doi: 10.4137/LPI.S31781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vance J.E., Steenbergen R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005;44:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Athenstaedt K., Daum G. Phosphatidic acid, a key intermediate in lipid metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;266:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur R., Naik A., Panda A., Raghu P. Regulation of membrane turnover by phosphatidic acid: cellular functions and disease implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:83. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi K., Roth M.G., Ktistakis N.T. Phosphatidic acid formation by phospholipase D is required for transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siddhanta A., Backer J.M., Shields D. Inhibition of phosphatidic acid synthesis alters the structure of the Golgi apparatus and inhibits secretion in endocrine cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12023–12031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmon O., Laguerre F., Riachy L., Delestre-Delacour C., Wang Q., Tanguy E., et al. Chromogranin A preferential interaction with Golgi phosphatidic acid induces membrane deformation and contributes to secretory granule biogenesis. FASEB J. 2020;34:6769–6790. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000074R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanguy E., Coste de Bagneaux P., Kassas N., Ammar M.R., Wang Q., Haeberle A.M., et al. Mono- and poly-unsaturated phosphatidic acid regulate distinct steps of regulated exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. Cell Rep. 2020;32 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanguy E., Wolf A., Montero-Hadjadje M., Gasman S., Bader M.F., Vitale N. Phosphatidic acid: mono- and poly-unsaturated forms regulate distinct stages of neuroendocrine exocytosis. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2021;79 doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2020.100772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanguy E., Wolf A., Wang Q., Chasserot-Golaz S., Ory S., Gasman S., et al. Phospholipase D1-generated phosphatidic acid modulates secretory granule trafficking from biogenesis to compensatory endocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2022;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2021.100844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noh J.Y., Lim K.M., Bae O.N., Chung S.M., Lee S.W., Joo K.M., et al. Procoagulant and prothrombotic activation of human erythrocytes by phosphatidic acid. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;299:H347–H355. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01144.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putta P., Rankenberg J., Korver R.A., van Wijk R., Munnik T., Testerink C., et al. Phosphatidic acid binding proteins display differential binding as a function of membrane curvature stress and chemical properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2709–2716. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owusu Kwarteng D., Gangoda M., Kooijman E.E. The effect of methylated phosphatidylethanolamine derivatives on the ionization properties of signaling phosphatidic acid. Biophys. Chem. 2023;296 doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2023.107005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doktorova M., Heberle F.A., Kingston R.L., Khelashvili G., Cuendet M.A., Wen Y., et al. Cholesterol promotes protein binding by affecting membrane electrostatics and solvation properties. Biophys. J. 2017;113:2004–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grouleff J., Irudayam S.J., Skeby K.K., Schiott B. The influence of cholesterol on membrane protein structure, function, and dynamics studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:1783–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda M., Longnecker R. Cholesterol is critical for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A trafficking and protein stability. Virology. 2007;360:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxena R., Chattopadhyay A. Membrane cholesterol stabilizes the human serotonin(1A) receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:2936–2942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharya S., Haldar S. Interactions between cholesterol and lipids in bilayer membranes. Role of lipid headgroup and hydrocarbon chain-backbone linkage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1467:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demel R.A., Van Deenen L.L.M., Pethica B.A. Monolayer interactions of phospholipids and cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (Bba) - Biomembr. 1967;135:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMullen T.P.W., Lewis R.N.A.H., McElhaney R.N. Cholesterol-phospholipid interactions, the liquid-ordered phase and lipid rafts in model and biological membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid. 2004;8:459–468. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vist M.R., Davis J.H. Phase equilibria of cholesterol/dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine mixtures: 2H nuclear magnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry. Biochemistry. 1990;29:451–464. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silvius J.R. Role of cholesterol in lipid raft formation: lessons from lipid model systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1610:174–183. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boughter C.T., Monje-Galvan V., Im W., Klauda J.B. Influence of cholesterol on phospholipid bilayer structure and dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:11761–11772. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b08574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lange Y. Disposition of intracellular cholesterol in human fibroblasts. J. Lipid Res. 1991;32:329–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikonen E. Mechanisms of cellular cholesterol compartmentalization: recent insights. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018;53:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doktorova M., Symons J.L., Zhang X., Wang H.-Y., Schlegel J., Lorent J.H., et al. Cell membranes sustain phospholipid imbalance via cholesterol asymmetry. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.07.30.551157. [preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buwaneka P., Ralko A., Liu S.L., Cho W. Evaluation of the available cholesterol concentration in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. J. Lipid Res. 2021;62 doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doktorova M., Symons J.L., Levental I. Structural and functional consequences of reversible lipid asymmetry in living membranes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:1321–1330. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00688-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S.-L., Sheng R., Jung J.H., Wang L., Stec E., O'Connor M.J., et al. Orthogonal lipid sensors identify transbilayer asymmetry of plasma membrane cholesterol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:268–274. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y., Bulkley D.P., Xin Y., Roberts K.J., Asarnow D.E., Sharma A., et al. Structural basis for cholesterol transport-like activity of the hedgehog receptor patched. Cell. 2018;175:1352–1364.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zorca S., Freeman L., Hildesheim M., Allen D., Remaley A.T., Taylor J.G., et al. Lipid levels in sickle-cell disease associated with haemolytic severity, vascular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Br. J. Haematol. 2010;149:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaya A., Martinez Triguero M., Reganon E., Vila V., Martinez Sales V., Sola E., et al. Erythrocyte membrane composition in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2008;40:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fonseca A.C., Resende R., Oliveira C.R., Pereira C.M. Cholesterol and statins in Alzheimer's disease: current controversies. Exp. Neurol. 2010;223:282–293. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puglielli L., Tanzi R.E., Kovacs D.M. Alzheimer's disease: the cholesterol connection. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nn0403-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason R.P., Shoemaker W.J., Shajenko L., Chambers T.E., Herbette L.G. Evidence for changes in the Alzheimer's disease brain cortical membrane structure mediated by cholesterol. Neurobiol. Aging. 1992;13:413–419. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90116-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridsdale A., Denis M., Gougeon P.Y., Ngsee J.K., Presley J.F., Zha X. Cholesterol is required for efficient endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport of secretory membrane proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1593–1605. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.daCosta C.J., Ogrel A.A., McCardy E.A., Blanton M.P., Baenziger J.E. Lipid-protein interactions at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. A functional coupling between nicotinic receptors and phosphatidic acid-containing lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:201–208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamouda A.K., Sanghvi M., Sauls D., Machu T.K., Blanton M.P. Assessing the lipid requirements of the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4327–4337. doi: 10.1021/bi052281z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettegrew J.W., Panchalingam K., Hamilton R.L., McClure R.J. Brain membrane phospholipid alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem. Res. 2001;26:771–782. doi: 10.1023/a:1011603916962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gobbi M., Re F., Canovi M., Beeg M., Gregori M., Sesana S., et al. Lipid-based nanoparticles with high binding affinity for amyloid-beta1-42 peptide. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6519–6529. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chauhan A., Ray I., Chauhan V.P. Interaction of amyloid beta-protein with anionic phospholipids: possible involvement of Lys28 and C-terminus aliphatic amino acids. Neurochem. Res. 2000;25:423–429. doi: 10.1023/a:1007509608440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dante S., Hauss T., Dencher N.A. Cholesterol inhibits the insertion of the Alzheimer's peptide Abeta(25-35) in lipid bilayers. Eur. Biophys. J. 2006;35:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z., Rand R.P. The influence of cholesterol on phospholipid membrane curvature and bending elasticity. Biophys. J. 1997;73:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strawn L., Babb A., Testerink C., Kooijman E.E. The physical chemistry of the enigmatic phospholipid diacylglycerol pyrophosphate. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:40. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graber Z.T., Gericke A., Kooijman E.E. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate ionization in the presence of cholesterol, calcium or magnesium ions. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2014;182:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graber Z.T., Kooijman E.E. Ionization behavior of polyphosphoinositides determined via the preparation of pH titration curves using solid-state 31P NMR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1009:129–142. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-401-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graber Z., Owusu Kwarteng D., Lange S.M., Koukanas Y., Khalifa H., Mutambuze J.W., et al. The electrostatic basis of diacylglycerol pyrophosphate-protein interaction. Cells. 2022;11:290. doi: 10.3390/cells11020290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kooijman E.E., King K.E., Gangoda M., Gericke A. Ionization properties of phosphatidylinositol polyphosphates in mixed model membranes. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9360–9371. doi: 10.1021/bi9008616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeniou-Meyer M., Zabari N., Ashery U., Chasserot-Golaz S., Haeberle A.M., Demais V., et al. Phospholipase D1 production of phosphatidic acid at the plasma membrane promotes exocytosis of large dense-core granules at a late stage. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21746–21757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kassas N., Tanguy E., Thahouly T., Fouillen L., Heintz D., Chasserot-Golaz S., et al. Comparative characterization of phosphatidic acid sensors and their localization during frustrated phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:4266–4279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.742346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vitale N., Moss J., Vaughan M. Molecular characterization of the GTPase-activating domain of ADP-ribosylation factor domain protein 1 (ARD1) J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2553–2560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thahouly T., Tanguy E., Raherindratsara J., Bader M.F., Chasserot-Golaz S., Gasman S., et al. Bovine chromaffin cells: culture and fluorescence assay for secretion. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021;2233:169–179. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1044-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poea-Guyon S., Ammar M.R., Erard M., Amar M., Moreau A.W., Fossier P., et al. The V-ATPase membrane domain is a sensor of granular pH that controls the exocytotic machinery. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:283–298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201303104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gabel M., Delavoie F., Demais V., Royer C., Bailly Y., Vitale N., et al. Annexin A2-dependent actin bundling promotes secretory granule docking to the plasma membrane and exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2015;210:785–800. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chakraborty S., Doktorova M., Molugu T.R., Heberle F.A., Scott H.L., Dzikovski B., et al. How cholesterol stiffens unsaturated lipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:21896–21905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004807117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magarkar A., Dhawan V., Kallinteri P., Viitala T., Elmowafy M., Rog T., et al. Cholesterol level affects surface charge of lipid membranes in saline solution. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5005. doi: 10.1038/srep05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graber Z.T., Jiang Z., Gericke A., Kooijman E.E. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate ionization and domain formation in the presence of lipids with hydrogen bond donor capabilities. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2012;165:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kessel A., Ben-Tal N., May S. Interactions of cholesterol with lipid bilayers: the preferred configuration and fluctuations. Biophys. J. 2001;81:643–658. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lorent J.H., Levental K.R., Ganesan L., Rivera-Longsworth G., Sezgin E., Doktorova M., et al. Plasma membranes are asymmetric in lipid unsaturation, packing and protein shape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:644–652. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Symons J.L., Doktorova M., Levental K.R., Levental I. Challenging old dogma with new tech: asymmetry of lipid abundances within the plasma membrane. Biophys. J. 2022;121:289a–290a. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cooper R.A. Influence of increased membrane cholesterol on membrane fluidity and cell function in human red blood cells. J. Supramol. Struct. 1978;8:413–430. doi: 10.1002/jss.400080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang Z., Redfern R.E., Isler Y., Ross A.H., Gericke A. Cholesterol stabilizes fluid phosphoinositide domains. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2014;182:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demel R.A., Yin C.C., Lin B.Z., Hauser H. Monolayer characteristics and thermal behaviour of phosphatidic acids. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1992;60:209–223. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(92)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kooijman E.E., Burger K.N. Biophysics and function of phosphatidic acid: a molecular perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:881–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cullis P.R., de Kruijff B. Lipid polymorphism and the functional roles of lipids in biological membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;559:399–420. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(79)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yesylevskyy S.O., Demchenko A.P. How cholesterol is distributed between monolayers in asymmetric lipid membranes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2012;41:1043–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00249-012-0863-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang J., Xue R., Ong W.-Y., Chen P. Roles of cholesterol in vesicle fusion and motion. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1371–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Churchward M.A., Rogasevskaia T., Höfgen J., Bau J., Coorssen J.R. Cholesterol facilitates the native mechanism of Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 20):4833–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferraz-Nogueira J.P., Diez-Guerra F.J., Llopis J. Visualization of phosphatidic Acid fluctuations in the plasma membrane of living cells. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolinski H., Hofbauer H.F., Hellauer K., Cristobal-Sarramian A., Kolb D., Radulovic M., et al. Seipin is involved in the regulation of phosphatidic acid metabolism at a subdomain of the nuclear envelope in yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1851:1450–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baillie G.S., Huston E., Scotland G., Hodgkin M., Gall I., Peden A.H., et al. TAPAS-1, a novel microdomain within the unique N-terminal region of the PDE4A1 cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase that allows rapid, Ca2+-triggered membrane association with selectivity for interaction with phosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28298–28309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hofbauer H.F., Gecht M., Fischer S.C., Seybert A., Frangakis A.S., Stelzer E.H.K., et al. The molecular recognition of phosphatidic acid by an amphipathic helix in Opi1. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217:3109–3126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201802027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tanguy E., Kassas N., Vitale N. Protein(-)Phospholipid interaction motifs: a focus on phosphatidic acid. Biomolecules. 2018;8:20. doi: 10.3390/biom8020020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Drabik D., Czogalla A. Simple does not mean trivial: behavior of phosphatidic acid in lipid mono- and bilayers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:11523. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the current submission and in the supplementary data section. Primary data sets supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.