Abstract

Youth‐led participatory action research (YPAR) engages young people as partners in rigorous research inquiry to guide and inform collective action. Scholars interested in YPAR have notable investment in social justice and activist values, which at times come in direct tensions within their doctoral training and/or professional roles within academia. One monumental hurdle in conducting YPAR is obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The goal of this manuscript, therefore, is to transparently and humbly share some of the heart work we have done in navigating the IRB. In partnership with IRB directors who are co‐authors, we discuss several choice points in obtaining IRB approval. Challenges include: (1) advocating for youth to have co‐investigator status on the IRB application, (2) training youth in research ethics, (3) strategically crafting a YPAR application that attends to the evolving and emerging nature of the research, (4) obtaining approval to compensate youth for their time as researchers, and (5) planning for diverse youth dissemination strategies that may challenge principles of anonymity. In discussing these choice points, we will share examples from our own work, strategies, and resources to support current and future aspiring YPAR scholars.

Keywords: youth‐participatory action research, Institutional Review Boards, community‐based, ethics

Highlights

Youth participatory action research scholars often struggle to navigate the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application process.

Three illustrative case studies are provided across diverse university contexts and project topics.

Co‐created strategies with IRB directors are shared to support future youth‐led participatory action research research efforts.

INTRODUCTION

In youth‐led participatory action research (YPAR), youth are leaders or co‐creators in research that aims to change systems that impact their lives (Suleiman et al., 2021; Teixeira et al., 2021). Scholars interested in YPAR have notable investment in community psychology values, such as social justice and advocacy, which at times come in direct tensions with professional training, roles, research processes, and/or paradigms within academia (Teixeira et al., 2021). One common challenge when planning for YPAR is navigating the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application process and/or office of Research and Sponsored Programs. These entities are notable gatekeepers to the conduct of research and are often oriented in post‐positivist biomedical perspectives. Such values run counter to participatory research that attempts to locate expertize within the community and honor the cultural nuances and sociohistorical realities of youth from the majority of the globe (Teixeira et al., 2021). Community psychologists have noted the value of sharing process‐oriented work in identifying strategies for engaging in community‐based partnerships (Campbell & Morris, 2017).

The goal of this paper, therefore, is to transparently and humbly share some of the challenging and rewarding work we have done in navigating the IRB process and institutional policies. We disclose this work in recognition of our own positionalities. Currently, we occupy roles as tenured and nontenured faculty, a postdoctoral scholar, as well as IRB board members and directors. We are situated in both smaller‐teaching institutions, as well as larger research‐focused institutions. Thus, we aim to discuss several choice points and challenges in obtaining IRB approval across diverse institutions, as well as highlight key strategies and resources. We begin this paper with an overview of YPAR. Then, we discuss the formation and role of the IRB in relation to research. Next, we review the literature surrounding tensions between YPAR and the traditional IRB process. We then present overlapping challenges and co‐developed strategies that we have employed to obtain project approval. We conclude with a discussion around implications, as well as next steps for advancing such work. At the heart of this paper is our love letter to other scholars, researchers, and IRB staff who value research conducted in power‐sharing partnerships with youth. We hope sharing these stories will help demystify the IRB application process, provide strategies to navigate the IRB application and begin to foster a community of support outside the confines of these journal pages.

LITERATURE REVIEW

YPAR overview

YPAR is a form of community‐based participatory research, in which youth and adults are engaged as co‐collaborators in a power‐sharing research partnership (Ozer, 2016; Suleiman et al., 2021). YPAR consists of four iterative stages: (a) problem identification, (b) data collection, (c) data analysis, and (d) social action (Ozer, 2016). In the problem identification stage, youth and adults explore and identify root causes surrounding issues of importance within young peoples' communities and then craft research questions to rigorously and empirically explore such topics (Kohfeldt et al., 2011). In the data collection stage, with the support of adults, youth identify, design, pilot, and enact a multi‐faceted data collection plan (Akom et al., 2016). In the data analysis stage, youth and adults engage in rigorous, systematic analysis, and critical discourse to make sense of and identify key leverage points to inform social action (Foster‐Fishman et al., 2010). Lastly, youth engage in acts of dissemination, advocacy, and organizing sharing their findings with key decision‐makers (Kirshner, 2015).

A core YPAR principle is that youth are agentic whole beings, who are not solely the subjects of our research, but rather active co‐collaborators capable of identifying, analyzing, and re‐imagining new worlds and possibilities (Toraif et al., 2021). Drawing on the teachings of Brazilian educator and activist Paulo Friere (as well as other critical liberation psychologists), YPAR stresses the value of consciousness‐raising discussions initiated through youths' own experiences with the scaffolded support of research tools and analytic frames to translate such discourse into root‐cause analysis and collective action (Berg et al., 2009; Freire, 2021). YPAR challenges positivist paradigms of knowledge construction, which often stress that such processes are research‐led. Instead, YPAR emphasizes the value of community voice (Teixeira et al., 2021). YPAR intersects with decolonial scholarship and values, as Silva and the collective Silva and Gatas (2021) highlight its potential as a decolonial educational approach in which youth leverage research to deconstruct manifestations of ongoing colonialism within their everyday lives (Silva & Gatas, 2021). As we discuss below, such epistemological values come in direct tension with several premises set‐forth by IRBs.

Institutional Review Boards

IRBs emerged as a result of interconnected acts of violence (often racialized) towards minoritized groups in the name of “moving science forward” (Flicker et al., 2007, Sabati, 2019). The Nazi Eugenic experiments encompassed involuntary sterilization and euthanasia on Jews, racially and sexually minoritized communities, and individuals who were deaf, blind, or had Down syndrome to support a scientific agenda of “racial hygiene” (Grodin et al., 2018). In the United States, the Tuskegee Syphilis trials involved the withholding of a known treatment for syphilis from 399 Black men for American scientists to “document” the entire onset of a painful and life‐shortening disease (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). An additional example is the work of the “father of modern gynecology” Marion Sims, who performed experiments without anesthesia on enslaved Black women in Alabama for the purposes of gynecological experimentation (Owens, 2017). Sabati (2019) warns against describing such acts of violence as discrete and characterizing them as led by bad‐faith scientists as opposed to systematic patterns of “racialized accumulation” (p. 160) in which scientific research itself is used as a tool of power that benefits from the violence of communities of color and is further used to enforce narratives justifying racial inequities.

After over 40 years of abuse, journalistic coverage of the Tuskegee Experiment ignited a national “tipping point of public outcry” (Sabati, 2019, p. 1058). As a result, the Nuremberg Code and later the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki proposed guidelines to uphold the “ethical treatment of human subjects” in research. A fundamental requirement of most universities and publicly funded research is that an ethical review be conducted before engaging in research. Examples include the Belmont Report (Office of Secretary, 2005) and the Tri‐Council of Canada (Tri‐Council of Canada, 1998). Key components of these ethical guidelines include principles of autonomy, non‐maleficence and beneficence, and justice (Office of Secretary, 2005; Tri‐Council of Canada, 1998). Yet protocols enacted by the IRB to assess risk situate ethics within the bounds of specific research projects, thus obscuring deeper understandings of the historic and ongoing dimensions of power enacted in the name of research and governing institutional bodies (Patel, 2015; Sabati, 2019). Sabati (2019) describes such protocols as a form of “colonial unknowing” (p. 1057) that removes and decontextualizes the various dimensions of risk associated with research. For instance, this framing fails to consider the scientific interpretations of research interactions, which may further perpetuate marginalized communities as a source of failure or even harm. Such narratives can then be weaponized to justify oppressive and, at times, violent policies. Research approved by the IRB continues to stigmatize minoritized communities. Scholars stress that research is often conducted to advance academic careers at the expense of communities (Flicker et al., 2007; Schnarch, 2004). Thus, marginalized communities often feel over‐researched, misused, and at times exploited by researchers and institutions. Such exchanges often occur when researchers do not give back to the community and perpetuate deficit‐focused narratives (Flicker et al., 2007; Schnarch, 2004).

Participatory action research and institutional tensions

Researchers have documented challenges for proposing participatory action research (PAR) to IRBs (Blake, 2007; Flicker et al., 2007; Shore, 2007; Teixeira et al., 2021; Ritterbusch, 2012; Van den Hoonaard, 2001). IRB protocols are often challenging to develop that accommodate the open‐endedness and emergent nature of PAR methodologies, as they often require pre‐determined: research topics, questions, and hypotheses, as well as finalized instruments (Abraczinskas et al., 2022; Blake, 2007; Shore, 2007; Van den Hoonaard, 2001). In enforcing such procedures, the IRB often places restrictions on the scope and range of authentic participant input and co‐creation that can occur within the research process (Van den Hoonaard, 2001). Furthermore, other institutional entities and funders tend to emphasize researcher and institutional ownership over the research findings, with protections that make it challenging to fully share data ownership with community partners.

In the context of youth‐led research, scholars have also stressed that IRBs can also perpetuate adultism (Ritterbusch, 2012; Teixeira et al., 2021). Adultism consists of behaviors, attitudes, and criteria reinforcing the view that adults “know better” than youth (Kennedy et al., 2019). Such sentiments, when actualized in the context of research, may consist of adults having the authority to make decisions on behalf of youth. Researchers often call into question youth's judgment and ability to engage in non‐biased rigorous and systematic empirical‐based research (Lewis, 2012; Perry‐Hazan, 2016). Within the context of the IRB, these ideologies may also manifest in the designation and framing of children and youth as “vulnerable populations” in need of protection (Ritterbusch, 2012; Teixeira et al., 2021). Although such language is in part a safeguard to combat power dynamics and acts of coercion conducted by researchers onto participants, it also asserts that children and youth are less capable of making meaningful decisions, thus limiting their ability to shape research designs or partake in action research. In practice, the multi‐layered protections within the IRB surrounding youth can obstruct the ability for them to participate as both researchers and co‐creators in knowledge production. Such restrictions limit opportunities for youth (particularly those from marginalizing groups) to reconstruct, reimagine, and foster narratives of social disruption.

Teixeira and colleagues (2021) warn YPAR scholars of the implications for engaging in “local workarounds” (p. 149), which they describe as steps for obtaining IRB approval with the least resistance. For instance, IRB‐approved YPAR often designates youth researchers as participants rather than co‐investigators. Such a designation is often done to avoid IRB pushback but has implications surrounding young peoples' voices in the research design, data ownership, and the ability to disseminate. Campbell and Morris (2017) note ethical codes enforced by IRBs are one facet of a complex ethical framework that community psychologists grapple with when working to uphold values of social justice and liberation. Our paper aims to add to this literature by discussing challenges we have encountered in the IRB review process as well as offering strategies in line with values of equity, empowerment, and decolonial frameworks (Dutta, 2018).

METHODOLOGY

Below, we describe our own work to highlight key challenges and strategies for YPAR researchers navigating the IRB review process. Our process for identifying these challenges was twofold. First, as a writing team, we transparently shared our hesitations for engaging in YPAR, our anxiety around the IRB application process, the challenges we encountered in obtaining IRB approval, as well as our strategies, reflections, and lessons learned. For most of us, these experiences were often navigated in isolation, in which we often felt disheartened by the process. Yet, some of us did have valuable contacts who generously shared their time and resources.

Second, we facilitated a brainstorming session with the Life Course Intervention Resource Network (YPAR Node). This group is funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the Health Researchers and Service Administration. Hosted by the University of California Los Angeles, it brings diverse groups together (i.e., researchers, providers, and community members) to discuss opportunities for transformative change and to optimize health outcomes. The YPAR node convenes researchers, practitioners, and youth to learn from one another, codevelop empirical evidence, and collaborate on strategies for advancing youth well‐being and development through policy, community development, and scholarship. We facilitated brainstorming sessions with team members in small groups over Zoom to discuss challenges and strategies for obtaining IRB approval. We then shared our own examples with the group so as not to influence the initial brainstorming. We took copious notes on Google Docs to transparently highlight areas to expand upon and refine. This session served as a validity check on the challenges our writing team identified and allowed us to expand our list of challenges, resources, and strategies.

Author's positionality

As authors, we occupy multiple intersecting identities, including white, bi‐racial, Black, Latina, cisgender, feminist, Jewish, first generation, highly educated, faculty, and university staff. We come to this work informed by our socio‐cultural backgrounds that both enhance and limit what we do or do not see. Our hope in engaging in this research is to highlight opportunities to further support scholars and IRBs invested in community‐based youth‐led research methods. In the writing of this paper, we challenged ourselves to recognize that all our work is situated within institutions built on the unceded lands of the Kalapuya (Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, n.d.), Potano (American Indian and Indigenous Studies, 2024), Seminole, (Seminole Tribe of Florida, n.d.), Nanticoke Lenni‐Lenape (Nanticoke Lenni‐Lenape, n.d.), Wampanoag (Wampanoag Tribe, n.d.), and Massachusett People (The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, n.d.). As IRB directors contributing this piece, at times, we had to educate our academic co‐authors on the reach and scope of the IRB as compared to other acting institutional entities (as described in detail in the sections below). Lastly, as a collective group, we believe that challenging the IRB to better support YPAR requires key actors working both within and outside of such systems (Kloos et al., 2012).

Key challenges and strategies for navigating the IRB and other institutional entities

Below, we highlight key challenges that emerged from our own work and discussions with the Life Course Intervention Research Network (YPAR Node). These challenges include: (1) advocating for youth to have coinvestigator status on the IRB application, (2) training youth in research ethics, (3) strategically crafting a YPAR application that attends to the evolving and emerging nature of the research, (4) obtaining approval to compensate youth for their time as researchers, and (5) planning for diverse youth dissemination strategies that may challenge principles of anonymity. This list is by no means exhaustive, and we hope to support further discourse around these challenges.

Youth researchers' role within the IRB application

One of the key tenets of YPAR is a youth‐led or a power‐sharing youth‐adult partnered research process, in which decisions are made collaboratively (Ozer, 2016). Applying this value to the IRB application can be tricky, depending on institutional policies. Some institutions are flexible and allow youth to be both participants and researchers; thus, designating them as co‐investigators is not a challenge. Other institutions do not allow that overlap, which creates challenges related to youths' role in the project. For example, if they are designated participants rather than co‐investigators, they may be subject to the participant payment system and receive a much lower amount than what they could receive as a coinvestigator. Policies surrounding payment may also fall outside the IRB purview and be a requirement of a sponsor and/or the office of research and sponsored programs. Youth researchers' role on the IRB can also impact whether they can be formally recognized for their work, such as including their names on conference presentations (i.e., participants' identities are protected).

Research ethics in YPAR

Human subjects training is a type of education designed to ensure that researchers understand the ethical, legal, and practical considerations involved in conducting research with people (Cohen, 2000). The Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) is one of the most commonly used options for human subjects research at colleges and universities. CITI is an online training program that provides education on human subjects research, including topics such as informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, data management, and ethical considerations. Many universities contract with CITI, and researchers can complete an online training at their own pace. Some IRBs allow external researchers to affiliate with the home institution to access CITI training. For instance, at Fordham University, high school students conducting research in the summer or in afterschool programs can access the online CITI training courses through the university. Some universities offer their own training programs, and there are also other online training programs available such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Human Subjects Research Training program, the Social and Behavioral Research Best Practices Course, and the American Psychological Association (APA) Human Subjects Research and Ethical Issues online course. Regardless of the program, online training may or may not be suitable for youth researchers due to developmental fit or practical constraints (e.g., time commitment, program access, and computer accessibility).

Most training programs were created for adult researchers with a college‐level education. Therefore, youth partners may not understand training modules due to lower reading comprehension skills, use of professional jargon, and/or lack of background knowledge in the field. Additionally, some training programs may require an institutional partnership that makes them inaccessible to young people who are not affiliated with a university or another research‐based institution. Youth co‐investigators, including students, may also be limited by the amount of time they can dedicate to human subjects ethics training while simultaneously balancing competing demands, including school, work, and/or other interests. Human subjects training does not provide an opportunity to unpack the colonizing history of research (Sabati, 2019), nor does it offer a framework to engage in ongoing critical reflection throughout the research endeavor (Campbell & Morris, 2017). Therefore, adult partners need to consider the importance of ethics training for their youth partners, while making sure that the training is developmentally appropriate, feasible, and holistically attuned to youths' realities.

Timing

YPAR projects may range from a few sessions to regular meetings over several years and everything in between (Kennedy et al., 2019). Although beyond the scope of this paper, timing is an important factor to consider regarding YPAR. Systematic reviews have found that longer projects tend to report stronger outcomes surrounding the depth of youth engagement as well as setting level changes (see Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2019). In the context of equity, adult partners must also consider timing within the contextual constraints in which the youth researchers reside. For instance, adult partners running YPAR within a school setting often operate during one semester (i.e., 4 months) or one academic year (i.e., 9 months); but meetings may be infrequent due to competing demands (Anderson, 2020). Other investigators may work outside school hours (e.g., weekends, summers), yet still face competing constraints (e.g., transportation, competition with other extracurricular activities, work schedules) (Abraczinskas et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2021). Therefore, another challenge that investigators face is planning the timeline for an accessible, meaningful, yet feasible project. From a researcher's perspective, it may be difficult to submit and obtain IRB approval for a project with a limited timeframe (e.g., daily sessions over 1 month, bi‐weekly meetings across one semester). From an IRB perspective, there may be staffing challenges in providing quick approvals and turn‐around requests. Furthermore, data collection may take significantly longer than the researcher had anticipated. By design, YPAR projects are collaborative and youth‐informed. Yet, given the logistics within a specific IRB or institution may make it challenging for the adult partner to submit the IRB application before onboarding youth partners.

Compensation

Participatory research values emphasize the importance of compensating people with lived experience equitably for their time (Anderson, 2020). Yet, there are significant roadblocks to paying youth researchers. When YPAR is implemented in schools, it may not be feasible to pay youth for their time due to school policies. Thus, YPAR is often offered as an elective class for credit or as an afterschool program as an extracurricular activity (Anderson, 2020). Though these experiences are meaningful, they can exclude the most marginalized youth, who may need to choose other options that provide compensation (Abraczinskas et al., 2022). Restrictions at the federal, state, funder, and university (office of research and sponsored programs) can limit the amount that youth can be paid. Some university offices of research and sponsored programs do not allow cash payment, while others allow it but have additional hoops to jump through to do so, which takes up valuable time. Additionally, these offices may have a cutoff for when participants need to submit their social security number for payment and fill out a 1080 tax form; these deadlines are often tied to state and/or federal policies. Such documentation adds an extra barrier for youth who navigate an immigration system that perpetuates violence and constant feelings of fear and vulnerability (Buckingham et al., 2021). Regarding paying youth equitably for their time, if the youth are listed as participants rather than co‐investigators in the IRB, the IRB may be worried about coercion to participate and also require parental consent for payment, making partnering with youth under the age of 18 an additional challenge.

Data ownership

In YPAR, youth‐researchers, in partnership with adults, actively gather community‐based data to help inform and guide points of advocacy (Kirshner, 2015). This data can take the form of both qualitative (interviews, focus groups, arts‐based methods) and quantitative (surveys) methods. Such data is typically leveraged to help inform strategic social action and advocacy (Kornbluh, 2023). For instance, key findings might be shared in conversation with decision‐makers or disseminated through public art or social media. In the context of the IRB, aggregated findings and research‐informed recommendations are often less vulnerable to breaking principles of confidentiality and anonymity. Yet, youth researchers may select to share more personal and identifying data for social organizing and advocacy purposes. Such dissemination practices may raise red flags for IRBs concerning the circulation of personal information and identification of participants (Kia‐Keating et al., 2017). Thus, the challenge becomes “Who owns the data?”

STRATEGIES FOR NAVIGATING THE IRB AND OTHER INSTITUTIONAL ENTITIES

Next, we highlight strategies for addressing these challenges in illustrative case studies below informed by our own work.

Case Study One: It's all about the timing!

This case study was led by the third author (Dr. Hoyt), a mid‐career researcher (who began the project pre‐tenure) at a mid‐size private institution within a large urban and diverse city. The study is based on a month‐long summer YPAR project, developed as part of a larger science pre‐professional summer program for 7–12th grade youth from lower socioeconomic homes and/or racial and ethnic backgrounds that are underrepresented in the sciences. The YPAR project was offered as an “Introduction to Psychology and Research” elective, meeting daily for 1 h over 1 month. The goal of this project was to get high school students interested in (and excited about) conducting research by letting them collect and analyze minimal risk (i.e., no more risk than you would encounter in your daily life) data from peers on topics of interest.

The biggest challenge for this project was timing, specifically the fast pace at which students needed to go from idea generation (e.g., identifying an issue), to conducting research on their issue (e.g., data collection involving human subjects), to dissemination/action (e.g., sharing what they learned with the community). To conduct a YPAR project in such a tight timeline requires careful planning and close coordination with the home institution's IRB. The adult partner (Dr. Hoty) requested to meet with the director of the IRB (Mrs. Kuchera) before starting the project and sustained close contact while drafting the original IRB protocol to ask questions and get feedback along the way. The initial conversation focused on a value orientation to YPAR and anticipated challenges for obtaining IRB approval. Engaging in open communication‐generated knowledge, established trust, and fostered bidirectional learning for both the adult partner (about the intricacies of human subjects research) and the IRB director (about YPAR). Another important consideration was the role of youth within the IRB application. Youth were co‐investigators (and not participants) in this project, which meant that they needed to complete ethics training and would have access to and ownership of the data required for analysis. Given that the YPAR project was offered as one of several elective classes, the high school co‐investigators did not receive monetary compensation. The goal was for students to complete the project during class, with the option to stay involved in dissemination efforts after the summer.

To prepare for the project, the adult partner submitted an IRB application in the spring, with a planned amendment to solidify study details in the second week of the month‐long program. This broad, “umbrella” application accounted for a wide range of minimal risk research that may be conducted as part of a psychology‐focused YPAR project, including methods (e.g., online survey, interviews, and photovoice) and measures (e.g., validated scales and sample interview questions); see Appendix A for example application. In some years, the summer program was framed around a central theme (e.g., mental health and sociopolitical stress).

During the amendment phase, the researchers provided more details on (1) the names and CITI certification of all co‐investigators, (2) the specific study aims within this overarching theme, (3) the data collection method that youth partners chose, and (4) the final versions of all study measures. Additionally, given that youth needed to be added as investigators, two class periods were dedicated to research ethics before the amendment submission. In the first class, adult partners (university faculty and undergraduate/graduate students) conducted a lecture and ran small group discussions on the historical development of human subject protection and current information on ethical issues (e.g., consent, confidentiality, and special populations). Youth researcher journals detailed their enjoyment of the dyadic approach to the training: “I enjoyed the lecture Dr. Hoyt gave overviewing the content in the CITI training (Journal Entry, 10/4/21).” In the second class, all youth registered for CITI through the University and completed an adapted version of the CITI Social and Behavioral Research course in a computer lab (i.e., a shortened course for “students conducting no more than minimal risk research”). Youth researchers shared that the training made them more reflective on the experience of participants: “I have to take it to heart; put myself into that research ‘what if this was me’” (Hoyt Field Note, 4/11/24).

The success of this “umbrella” IRB application with an amendment approach is contingent on the cooperation of the IRB. Although the “umbrella” IRB application can be submitted months in advance (and may need to be submitted early if full board IRB review is required), it is not likely that an amendment would be reviewed and approved in time to complete the data collection without clear communication between the adult partner and the IRB. In this case, the adult partner and IRB office decided on a specific (predetermined) date that the IRB amendment would be submitted to facilitate the quick turnaround (24–48 h) without burdening IRB staff with a last‐minute request. Once the amendment was approved, all investigators had access to the deidentified data on a shared (password protected) Google Drive. Any dissemination project (e.g., presentation) had to be approved by the full study team.

Case Study Two: Who owns the data?

This case study was led by Drs. Kornbluh and Bell. Dr. Kornbluh was, at the time, an early career researcher whose first academic position was at a teaching‐focused state institution. Dr. Bell was a master's student. Dr. Kornbluh obtained her first grant as a principal investigator (from the Spencer Foundation) to support all research activities. As a whole, the YPAR team consisted of two adult partners (university faculty and graduate student) partnering with seven undergraduate college students (ages 18 to 21 years old). Youth researchers identified as Black, Hmong, Pilipino, Latinx, Bi‐Racial, and Queer. The university was located in a rural county of Northern California. Youth researchers were actively engaged in antiracist organizing within their university and larger community funded through a multicultural center. After spending a year working with the organization, trust was established between the adult partners and the youth researchers to engage in a YPAR project. YPAR was identified as an organizing tool for youth researchers, helping them gather data and examine diverse information sources that could then be leveraged to place political as well as social pressure on decision‐makers (Kornbluh et al., 2022, 2021, 2023 for further study details).

Concerning the youth researchers' role on the IRB application, youth were co‐investigators in the YPAR project and selected a range of methods to capture their experiences of racism (i.e., surveys, focus groups, and photovoice). Regarding timing, the YPAR project was yearlong. An “umbrella” IRB application was also submitted at the beginning of the project, providing templates for various research methods (survey, focus group script, and photovoice protocol). As the project developed with youth researchers as co‐investigators, more specific amendments were submitted to meet the needs of the youth and community. The adult partner (Dr. Kornbluh) met with an IRB representative (a fellow colleague within the psychology department) over coffee, shared updates on the project progress, and explained the rationale for the amendments to get advice on documentation and any emerging ethical concerns. These ongoing conversations were critical in that they allowed the IRB to anticipate incoming amendments, reduced back‐and‐forth regarding the types of documentation needed and fostered a champion within the IRB around the goals of YPAR.

Youth researchers selected to use photovoice as both a research method and process for advocacy. Photovoice applies principles of ethnography and action research, in which youth assess conditions affecting their communities via individual photo documentation and collaborative consciousness‐raising group discussions (Lichty et al., 2019). Applying Sabati's (2019) critique that the IRB's conceptualization of risk is removed from the sociohistorical realities that youth from the majority of the globe encounter, the adult and youth partners in this case study found that the research ethics training within the university did not cover challenges for youth of color in utilizing photovoice to document systemic and interpersonal experiences of racism. To address this concern, the team co‐developed their own training. Within the ethics training, topics of consent, as well as subject and personal safety, were discussed. In particular, youth researchers explored sample photographs from the research team and then discussed the ethical implications of such documentation (i.e., safety of the photographer, identification of the subject, legality of activities captured, etc.). Lastly, a practice community walk was conducted in which youth researchers and the adult partners took cameras out into the community and discussed decision‐making processes for taking photographs. As one youth researcher noted, “this really helped you understand the power of a photograph” (Kornbluh Field Note, 4/5/18). As a result of the community walk, youth researchers advocated to modify the IRB protocol to protect their own safety. Specifically, they asserted the importance of using their own phones to take pictures as compared to digital cameras, which they felt may bring unwanted attention. As one youth researcher debriefed with the adult partner: “No way am I using a camera, I've got my phone” (Kornbluh Field Note, 4/5/18). This feedback was shared with the IRB (e.g., specifically with quotes from youth highlighting the racialized nature of such documentation), and modifications were allowed, enabling youth to have the choice of whether to use their phone or a digital camera.

Youth researchers were compensated for their time by the university multicultural center for running multicultural leadership activities. A portion of these activities included the YPAR project. Later in the project, youth felt comfortable disclosing that they often felt underpaid in other aspects of their work (e.g., hosting events for students and running clubs). Although challenges with compensation reflect a larger institutional issue, the ambiguity in the role of youth as both co‐investigators and employees within the university made it challenging for the IRB to intervene around compensation. This aspect of the case study was troubling to hear for our IRB co‐authors (who work at different institutions). In our debriefing, we noted that the institutional boundaries surrounding the IRB's oversight can hinder the agency's ability to advocate on behalf of issues of larger injustice. The adult partners documented in further detail their advocacy to the center and university on behalf of youth (Kornbluh et al., 2022). Upon reflection, putting aside resources (e.g., food, educational supplies, stipends) and a clear memorandum of understanding with the partnering organization (which may include a university entity) to support youth researchers as they become comfortable sharing their needs would be beneficial.

At the end of data collection, the YPAR team curated a public exhibit in which photographs and accompanying narratives were shared with key decision‐makers. The youth researchers wanted to have autonomy and ownership over the data to post photos from the exhibit on their personal social media accounts for organizing purposes. This request sparked concern from the IRB representative that the sharing of such information would identify subjects (i.e., other students) and the co‐investigators themselves within the photographs. Such a concern for “safety” may illuminate more paternalistic views that undermine youth researchers' own agency to navigate online spaces, a practice that they arguably engage with on a daily basis (Middaugh et al., 2022). To offset this concern, a data‐sharing agreement was created for the IRB. The research team co‐created a protocol detailing who had access to the data (the adult partners and youth researchers), the length of time the data would be accessible (length of study), and the storage and de‐identification process (ensuring photos and narratives were deidentified). Youth researchers proposed ways they could share photographs online that were deidentified to help raise public awareness. The adult partners provided photographic and narrative examples to the IRB to further highlight the process for de‐identification before submitting the amendment.

Case Study Three: Advocating for youth researchers as co‐investigators

This case study was led by the second author (Dr. Abraczinksas), an early career researcher on the tenure track at a large, research‐focused university in a small city in the southeastern United States. The project was funded federally (Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention) via a subcontract through the American Institutes for Research (a nonprofit). The purpose of the project was to engage youth with lived experience of parental incarceration in YPAR. It was conducted in partnership with two community‐based organizations. Organization one focused on peace‐building and restorative justice. Organization two, focused on assisting youth with obtaining their GED and job training, was the implementation site. The adult partner team included two university researchers (Dr. Abraczinksas and a graduate student), as well as a staff member from organization two.

The university team submitted an umbrella proposal to the IRB framing youths' initial role as participants in a YPAR training program. The proposal included the training protocol and evaluation measures. The purpose of this first phase was to evaluate the training and its impact on youth and the organization; thus, youths' experiences were assessed, and they were designated as participants. The university researchers were told by the IRB that the proposal would require a full board review. They submitted the proposal by the specified deadline, and had a zoom meeting a month later, during which the chair summarized the submission, the board members stated their perspectives and concerns (mainly around the incarceration topic), and asked the researchers for clarification around confidentiality, anonymity, and youth roles. The study was approved following revisions, and then young adult YPAR team members with lived experience of family member incarceration were recruited from organization two. The young adult team members identified as Black or African American, women, and were in their early 20's. Two of them had young children; all were in the workforce.

Compensating youth equitably for their time was a requirement of the funder and is also a goal of equity‐focused work. To maximize the amount of funds that could be used for youth pay and the project, the university researcher collaborated with organization one on the grant proposal. The funds were awarded to the organization, with Dr. Abraczinksas as an evaluator, with an agreement between the organization and the university. Notably, another challenge with payment is participants being taxed on their pay. To mitigate this challenge, the youth were paid via a training program stipend by organization two, which was not an extra burden because they already had a stipend structure set up for their own programming. The young adults were paid $45 per 1.5‐h session and attended two sessions a week for about a year. As needs came up, the organization and university researchers were able to modify the budget to meet youths' needs (e.g., gas cards). In the context of this study, allocating grant ownership with an outside organization provided Dr. Abraczinksas the flexibility to ensure youth researchers were equitably compensated.

The young adults participated in the initial stages of YPAR in the training program. The young adults chose to conduct interviews and focus groups to answer their question: what are the strengths and support needs of youth ages 12–22 who have had incarcerated parents? Once the youths' study proposal was solidified, the university researchers submitted an amendment to their initial application to include the young adults as co‐investigators, including the details about their proposed project. After submission, the IRB administrator sent a message requesting that the researchers meet with the university research office to talk about this option. In this discussion, the adult partner initiated the conversation by first explaining the goals, values, and processes surrounding both participatory research and YPAR. From this exchange, the research office representative shared that he thought the project was meaningful and that it could proceed. Yet, he wanted a new application as youth cannot be both participants and researchers. The adult partner created a new IRB application with the young adults in the role of co‐investigators on their designed study, which allowed them to be identified in conference presentations (Abraczinskas et al., 2022, publications (Abraczinskas et al., 2022), and other dissemination strategies.

Before the second IRB application could be submitted, the young adults had to obtain a university ID, create an IRB account, and complete ethics‐training (i.e., the general CITI training). The adult partners covered relevant information for the youths' specific study in a brief presentation and also partnered with the organizations to include strategies to support their wellbeing due to their lived experience on the topic. The adult partners assisted the YPAR team in completing the CITI training on computers. The young adults noted their appreciation of partnering with the adult partners surrounding the training: “What you went over was easy to understand and was important to our project to keep things private and keep kids safe.” (Abraczinksas, Field Note, 12/15/21). Yet, they also noted that questions within the CITI training could be confusing and, at times, not applicable to YPAR: “The post‐training IRB questions were confusing. Most did not seem like what we will do” (Abraczinksas, Field Note, 12/15/21). Notably, this university did not have a community‐friendly CITI training available. Once they passed, the young adults were added to the IRB application within the online system. It went to full board review and received approval, with the young adults listed as co‐investigators.

Due to their role as co‐investigators, the young adults could then collect data for their study. They received training to conduct focus groups over multiple sessions, and then led them independently with 16‐22‐year old's from their population of interest within community settings. Note that once they were approved as co‐investigators, data was no longer collected from young adults about their experiences in the program as participants, because they could not be in both roles. The young adults attended the Society for Research on Adolescence Conference in 2022 to present their work as co‐authors. They also were co‐authors of a published paper (see Abraczinskas et al., 2022). They have provided input on advocacy efforts around support for youth with incarcerated parents, such as free/reduced‐cost phone calls to incarcerated family members. As a result, Gainesville County now has a plan to make phone calls free for incarcerated individuals.

Regarding data ownership, due to IRB requirements because of the incarceration topic, the data is housed at the university PI's office within a secure online platform rather than at the organizations and required an additional certificate of protection (certificate of confidentiality) from the National Institute of Health to protect the data from subpoena in case details about crimes were disclosed. Whenever dissemination opportunities arise, the university researchers have an agreement with the young adults to discuss together how to move forward.

DISCUSSION

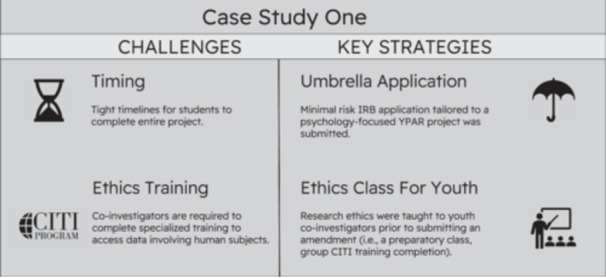

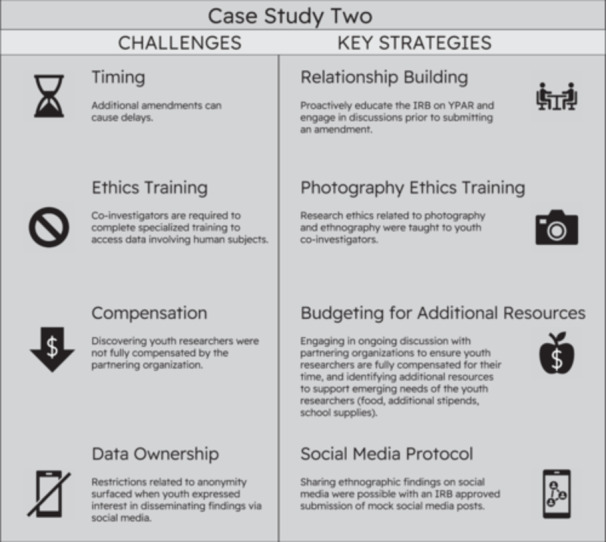

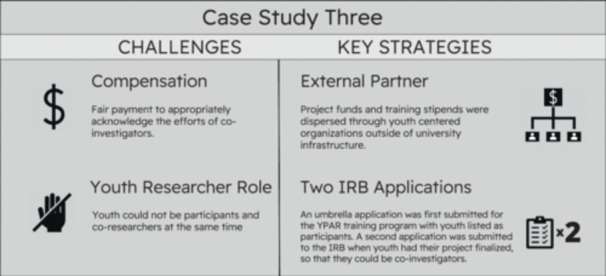

A core element of all three projects was the intentional, reciprocal, and transparent relationship fostered between the research team and the IRB. For the researchers, a critical first step within this relationship was educating the IRB on the nature of YPAR, the unique demands of the project, and an openness to feedback on how best to proceed with the application (see Appendix B, for example, informational flyer and potential conceptual framing). Such conversations were often framed by the researcher initially sharing a value orientation around YPAR (i.e., equity, social justice, and community service). From an IRB standpoint, working creatively and clearly with the researcher ensured proper safeguards were put into place that allowed the project to move forward. For larger institutions and medical schools, a designated “point person” within the IRB application could be tasked with supporting community‐engaged research. From an administrative lens, hiring IRB staff who are from the local community, have experience in community‐based research, and have a value orientation towards decolonial praxis and equity could further support institutional change efforts. Furthermore, involving, and compensating community members in the IRB review process may be another mechanism for ensuring ethical practices are upheld. Below, we summarize key strategies that emerged across cases for each identified challenge as well as note remaining concerns (Figures 1, 2, 3).

FIGURE 1.

YPAR Case Study 1. YPAR, youth‐led participatory action research.

FIGURE 2.

YPAR Case Study 2. YPAR, youth‐led participatory action research.

FIGURE 3.

YPAR Case Study 3. YPAR, youth‐led participatory action research.

Youth role on the IRB

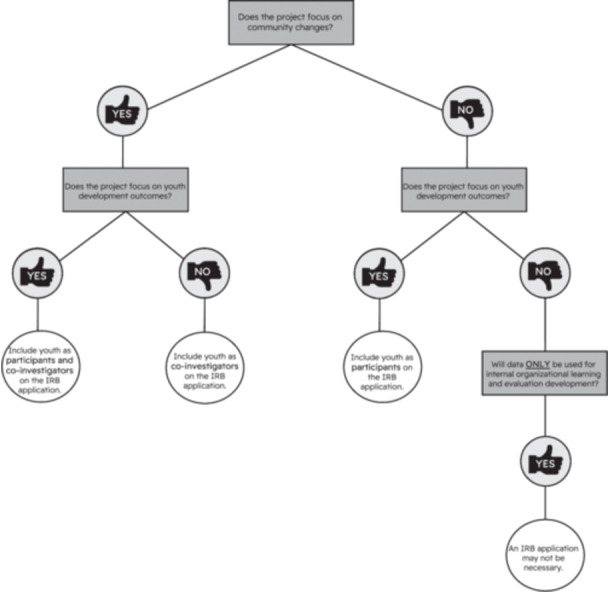

Researchers should set up a meeting with their IRB contact early on to describe YPAR, ideal youth roles and leadership within the project, and to ask how participatory work is typically structured within the application. To prepare for such discussions, researchers may find it beneficial to reflect on the following questions (see Figure 4 for visual):

-

1.

Who has a voice in the research design? For instance, if youth are collaborators in the design of the project as identified at the start, or anticipated over time, then having them as co‐investigators on the IRB application would be of great value.

-

2.

What are the desired outcomes of the research project? Does the project focus more on youth outcomes? In this case, the youth would be participants in the IRB application. Does the project focus more on setting‐level changes? In such cases, youth may play the role of co‐investigators. A YPAR project may also focus on a combination of outcomes. Thus, a comprehensive or multiple application(s) may need to be submitted.

-

3.

How might the data be utilized? Data utilization may include internal organizational learning and evaluation development, in which case an IRB application may not be necessary. The research may focus on youth personal development (i.e., how have youth changed resulting from the YPAR process). In such cases, an IRB application, in which youth are participants, would ordinarily be needed. Additionally, the project may be structured as a youth‐adult partnership, in which the data would be published in journals and presented with youth as co‐authors. In such a situation, an IRB application and youth coinvestigator role is likely needed. Lastly, a combination of the above could be a possibility, in which one comprehensive or multiple IRB application(s) may need to be submitted highlighting the different roles of the youth throughout the project, as well as details around data ownership and security protocols for the data sources gathered.

FIGURE 4.

YPAR decision tree. YPAR, youth‐led participatory action research.

The paths described above vary greatly by institution, so it is important to discuss the project with the IRB early in the planning stage. Additionally, it is valuable to find out from the IRB early regarding what is required for someone to be listed as a coinvestigator (e.g., a university ID, CITI training). Not knowing all the steps could significantly delay a project timeline. To further support scholars in developing an IRB application, we have crowdsourced example YPAR IRB applications from generous colleagues at various institutions and have made them openly available at (see https://yparhub.berkeley.edu) as well as on the Open Science Framework database (see https://osf.io/4j3sb/).

Researcher ethics training

Ethics training provided by the university was often not accessible or developmentally appropriate for youth researchers. Notably, some IRBs do allow youth researchers to access CITI training through a home university subscription, thus checking with one's own IRB is critical. Another strategy for ensuring youth comprehension around the training was in‐person group sessions to complete the university training modules. In such sessions, youth researchers and the adult partner (faculty, graduate student) work together. Such group work and scaffolded support can increase retention and meaningful engagement with training materials. Additional training that highlights the unique personal, cultural, and or community concerns for youth engaging in action research may also be needed. Recognizing the historic and ongoing oppression institutional agents embody, we stress that YPAR requires an ongoing reflection and praxis to ensure holistic and dynamic ethical challenges are addressed throughout an evolving project. Specifically, we note that engaging in YPAR (i.e., identifying social injustice, elevating youth voices, and decision‐maker power) can cause tensions and confrontational ethical challenges with other significant adults in young peoples' lives (see for further discussion, Bertrand et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2022; Kohfeldt et al., 2011). Thus, before engaging in YPAR, it is critical to spend time in the community, as well as assess the readiness of the setting to engage in YPAR and the skills and capacity of the adult researcher and available allies to address emerging challenges (Kornbluh et al., 2011). The strategies proposed above tend to emphasize the adult partner as the “expert” with regard to ethical training. Planning for training to ensure discussion formats that challenge traditional instructor‐style formats will allow for more co‐learning to occur. For instance, the youth researcher and adult partner can discuss ethical scenarios and share different perspectives regarding ethical concerns within and outside the scope of the IRB training.

Timing

Due to YPAR projects being collaborative and youth‐driven, it is challenging for adult partners to complete an IRB application before youth begin the YPAR project. To offset the emergent nature of the YPAR project and the work demands of the IRB, an “umbrella” IRB application may be a fruitful strategy in ensuring the IRB can review the potential scope and range of methods utilized ahead of the project. This method still provides youth researchers some autonomy and flexibility to select methods, create their own data collection instruments, and finalize the focus of the project. Yet, it's important to recognize that this strategy may, at times, require a particular research topic or array of topics to be predetermined. Notably, if the YPAR group has not yet decided the direction of the project, then decision‐making falls on the shoulders of the adult partner. To ensure a more democratized and collaborative process, the adult partner may wish to survey youth populations who will be recruited for the YPAR project or engage in discussions with local community partners to solicit community input on the potential direction and focus of the anticipated YPAR project.

Compensation

Researchers will need to make choices related to the feasibility of youth pay within their institution while recognizing that some of these restrictions may limit the participation of minoritized and marginalized youth most impacted by the inequities that YPAR projects seek to address. Researchers should learn about these processes, both at the sponsored program/finance, state or federal levels, and within their own IRB, early on, so that when they recruit youth, they can be transparent about what compensation entails. Strategies such as having a community‐based organization allocate funds for participant payment can allow greater flexibility and more equitable youth access to compensation. Such relationships, however, take time to develop to ensure youth are being fully supported. Creative budgeting can also allow for flexible funding to provide emerging resources and support based on the needs of the youth.

Data ownership

Some researchers have created research projects with IRB applications in which they are collecting evaluation data on the YPAR experience (Kornbluh et al., 2021). Data may include the developmental gains and systemic challenges experienced by youth researchers. Here, the youth own their data as it is outside the scope of the evaluation, and as such do not have the same restrictions in place for how they might leverage it (Ozer & Douglas, 2012). Other scholars have co‐created a database with youth (Abraczinskas et al., 2022). Thus, youth researchers go through IRB training, are listed as investigators, and are responsible for upholding principles of confidentiality when engaging in dissemination practices. Another option is to house the data at the university but have agreements around communication strategies related to how the data will be used (Kornbluh et al., 2022). Within the context of social media data dissemination, Kia‐Keating et al. (2017) challenge whether such restrictions should fall under the purview of the IRB as they ultimately infringe upon youth researchers privacy and autonomy.

Next steps for IRBs and institutional bodies

As IRB directors our institutions have made efforts to support researchers invested in community‐based research and learning. For instance, at Boston University, our Clinical & Translational Science Institute has a Community Engagement Program (CEP) that offers an array of support for researchers. One of the signature programs offered through the CEP is a monthly speaker series titled—“The Building a Culture of Community Engagement Speaker Series.” Takeaways and details from the series, as well as helpful research resources, were compiled in a year‐end report (see Boston University School of Social Work, 2023). Furthermore, the IRB has been in conversation with the director of CEP to explore avenues in which youth can be involved in the IRB review process itself. At Fordham University, there is a university‐wide effort to expand community engagement, including the Center for Community Engaged Learning (CEL) and an expansion of CEL course offerings (with administrative, social, and financial support from the Center). One of these CEL courses, PSYC 4855: Participatory Action Research (lead by Dr. Hoyt), is a 4‐credit undergraduate course, in which the college class partners with a local high school to run a semester‐long YPAR project as co‐investigators. This course is intended to (1) give undergraduate students the opportunity to apply their research training in a meaningful way, (2) give local high school students access to our college campus/resources and foundational training in research methods, and (3) and inspire youth co‐investigators to become scholar activists, empowering them to use these tools to make a difference in their local community.

Limitations

Our experiences are very much informed by the various universities we navigate. The diversity of our writing team is a strength, coming from universities that vary in focus (i.e., research and teaching), size, and geographic location. Furthermore, we vetted the strategies identified with the larger Life Course Intervention Research Network (YPAR Node). Reflectively, two of the case studies document time‐intensive partnering between IRB representatives (and directors) and academic researchers within smaller to mid‐sized teaching‐focused institutions. As such, our strategies may be more attuned to university settings that allow for more one‐on‐one interactions as compared to IRBs navigating larger research caseloads. In the context of case study three, Dr. Abraczinskas noted that conducting research within an institution that offers cooperative extension services offering a university‐wide infrastructure for partnering with local communities throughout the state may have increased the IRB's comfort with and exposure to community‐based methodologies. Yet, universities with cooperative extension services directly benefited from the Morill Act, which turned 11 million acres of indigenous land expropriated from tribal nations into money for these land grant institutions (referred to as land‐grab institutions, see Lee & Ahtone, 2020). All three academic research authors were very junior and engaging in YPAR for the first time (as professors) at their respective institutions. Due to such positionalities, the strategies we engaged in were likely more focused around collaboration and partnering, and less aimed at challenging and disrupting current IRB structures. Conducting a large‐scale survey would allow for a more global and inclusive assessment of the various roadblocks and strategies for obtaining IRB approval.

Our interpretation of the IRB experience is centered through an adult researcher and university‐director‐focused lens. Although we incorporated feedback from youth researchers around the ethics training, such responses are filtered through our own lens (i.e., field notes), and power dynamics may make it challenging for youth to feel comfortable critiquing such processes. Anonymized feedback formats from youth researchers and partnering agencies (community‐based organizations and schools) would allow us to further assess the strength of such strategies more holistically. As noted by our IRB co‐authors, various challenges described above (compensation, ethics training) are often outside the purview of the IRB. Further research in identifying where such restrictions lie (federal, state, funding agency, university offices) can allow targeted policy change. Such systemic analysis is critical in fully understanding the various facets and allocation of power within an institutional entity and how such units intersect with research efforts that have historically marginalized and continue to marginalize communities.

Recognizing the political context many universities are operating in and the outright censorship of academic research on issues of equity, homophobia, and racism, new strategies of resistance and partnership with the IRB are needed to support continued efforts to engage in YPAR. Lastly, reflecting upon our own co‐created strategies for navigating the IRB, we, as authors, upheld entrenched practices perpetuating adultism and asymmetric power structures and could have brokered potential dialogue and contact zones between youth researchers and the IRB directly throughout the application process. Thus, critical documentation is needed around the root causes and potential downstream consequences of such decisions. Furthermore, advocating and educating around YPAR to one's IRB should involve explicit discussions around adultism as well as the ethics beyond the collecting of research to that of use and dissemination.

CONCLUSION

Scholars interested in YPAR have notable hurdles and roadblocks for engaging in action research. We provide strategies for partnering with the IRB to obtain timely approval for meeting the real‐world conditions youth navigate, as well as ensure that youth have access to the role of co‐investigators. It is our hope that this paper furthers conversation and resource‐sharing amongst scholars passionate about and actively working to pursue YPAR research endeavors.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Mariah Kornbluh's projects were funded by the Spencer Foundation (#201800038), and William T. Grant Scholars Program (203522). Additional support for all authors was provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement U8DMC45901. We also gratefully acknowledge supplementary support from the Life Course Intervention Research Network (supported by the HRSA of the HHS under award UA6MC32492).

Kornbluh, M. , Abraczinskas, M. , Hoyt, L. T. , Bell, S. , Kuchera, M. , & Thomas, L. (2025). Navigating the Institutional Review Board and other institutional entities: An ode to aspiring YPAR scholars. American Journal of Community Psychology, 75, 102–116. 10.1002/ajcp.12773

REFERENCES

- Abraczinskas, M. , Adams, B. L. , Vines, E. , Cobb, S. , Latson, Z. , & Wimbish, M. (2022). Making the implicit explicit: An illustration of YPAR implementation and lessons learned in partnership with young adults who have experienced family member incarceration. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 3(3), 166–194. 10.1177/263207702210921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akom, A. , Shah, A. , Nakai, A. , & Cruz, T. (2016). Youth participatory action research (YPAR) 2.0: how technological innovation and digital organizing sparked a food revolution in East Oakland. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(10), 1287–1307. 10.1080/09518398.2016.1201609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Indian and Indigenous Studies . (2024). The archaeology and history of the Alachua and Potano people. University of Florida. https://guides.uflib.ufl.edu/AIIS/Potano_Alachua [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A. J. (2020). A qualitative systematic review of youth participatory action research implementation in US high schools. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1–2), 242–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. , Coman, E. , & Schensul, J. J. (2009). Youth action research for prevention: A multi‐level intervention designed to increase efficacy and empowerment among urban youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3–4), 345–359. 10.1007/s10464-009-9231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M. , Durand, E. S. , & Gonzalez, T. (2017). “We're trying to take action”: transformative agency, role re‐mediation, and the complexities of youth participatory action research. Equity & Excellence in Education, 50(2), 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, M. K. (2007). Formality and friendship: Research ethics review and participatory action research. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 411–421. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/789 [Google Scholar]

- Boston University School of Social Work (2023). Building a culture of community engagement speaker series: End of the year newsletter. Retrieved from: https://www.bu.edu/ssw/files/2023/08/BU-CTSI-End-of-Year-Newsletter-2023.pdf

- Buckingham, S. L. , Langhout, R. D. , Rusch, D. , Mehta, T. , Rubén Chávez, N. , Ferreira van Leer, K. , Oberoi, A. , Indart, M. , Paloma, V. , King, V. E. , & Olson, B. (2021). The roles of settings in supporting immigrants' resistance to injustice and oppression: A policy position statement by the society for community research and action: A policy statement by the society for community research and action: Division 27 of the American Psychological Association. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(3–4), 269–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R. , & Morris, M. (2017). The stories we tell: introduction to the special issue on ethical challenges in community psychology research and practice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3–4), 299–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani, C. , & Minkler, M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 37(3), 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . (September 4th, 2024). The U.S. public health service untreated syphilis study at Tuskege. Reterieved at: https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/about/index.html.

- Cohen, M. H. (2000). Beyond complementary medicine: Legal and ethical perspectives on health care and human evolution. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde . (n.d.). Our story. https://www.grandronde.org/history-culture/history/our-story/

- Dutta, U. (2018). Decolonizing “community” in community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 272–282. 10.1002/ajcp.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker, S. , Travers, R. , Guta, A. , McDonald, S. , & Meagher, A. (2007). Ethical dilemmas in community‐based participatory research: Recommendations for institutional review boards. Journal of Urban Health, 84(4), 478–493. 10.1007/s11524-007-9165-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster‐Fishman, P. G. , Law, K. M. , Lichty, L. F. , & Aoun, C. (2010). Youth ReACT for social change: A method for youth participatory action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1–2), 67–83. 10.1007/s10464-010-9316-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2021). Education for critical consciousness. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Grodin, M. A. , Miller, E. L. , & Kelly, J. I. (2018). The Nazi physicians as leaders in eugenics and “euthanasia”: lessons for today. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 53–57. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Hoonaard, W. C. (2001). Is research‐ethics review a moral panic? Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 38(1), 19–36. 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2001.tb00601.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H. , Anyon, Y. , Engle, C. , & Schofield Clark, L. (2022). Using intergroup contact theory to understand the practices of youth‐serving professionals in the context of YPAR: Identifying racialized adultism. Child & Youth Services, 43(1), 76–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H. , DeChants, J. , Bender, K. , & Anyon, Y. (2019). More than data collectors: A systematic review of the environmental outcomes of youth inquiry approaches in the United States. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(1–2), 208–226. 10.1002/ajcp.12321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kia‐Keating, M. , Santacrose, D. E. , Liu, S. R. , & Adams, J. (2017). Using community‐based participatory research and human‐centered design to address violence‐related health disparities among Latino/a youth. Family & Community Health, 40(2), 160–169. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, B. (2015). Youth activism in an era of education inequality (Vol. 2). NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos, B. , Hill, J. , Thomas, E. , Wandersman, A. , Elias, M. J. , & Dalton, J. H. (2012). Community psychology. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Kohfeldt, D. , Chhun, L. , Grace, S. , & Langhout, R. D. (2011). Youth empowerment in context: Exploring tensions in school‐based yPAR. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 28–45. 10.1007/s10464-010-9376-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluh, M. (2023). Making the case for youth participatory action research opportunities to enhance social developmental scholarship. Social Development, 32(3), 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluh, M. , Bell, S. , Vierra, K. , & Herrnstadt, Z. (2022). Resistance capital: Cultural activism as a gateway to college persistence for minority and first‐generation students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(4), 501–540. [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluh, M. , Johnson, L. , & Hart, M. (2021). Shards from the glass ceiling: Deconstructing marginalizing systems in relation to critical consciousness development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(1–2), 187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluh, M. , Watson, E. , & Foster‐Fishman, P. (2011). Expanding the scope of participatory action research: Include community context. Presented at the Annual National Outreach Scholarship Conference, Lansing, MI.

- Lee, A. , & Ahtone, T. (2020). Land grab universities. High Country News. Retrieved September 1, 2024: https://www.hcn.org/issues/52-4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities/

- Lichty, L. , Kornbluh, M. , Mortensen, J. , & Foster‐Fishman, P. (2019). Claiming online space for empowering methods: Taking photovoice to scale online. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 10(3), 1–26. https://journals.ku.edu/gjcpp/article/view/20692 [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh, E. , Bell, S. , & Kornbluh, M. (2022). Think before you share: building a civic media literacy framework for everyday contexts. Information and Learning Sciences, 123(7/8), 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- Nanticoke Lenni‐Lenape . (n.d.). About the Nanticoke Lenni‐Lenape . https://www.nlltribalnation.org/14-2/118-2/

- Office of Secretary . (2005). The Belmont Report. Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html [PubMed]

- Owens, D. C. (2017). Medical bondage: Race, gender, and the origins of American gynecology. University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, E. J. (2016). Youth‐Led participatory action research: Developmental and equity perspectives. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 50, 189–207. 10.1016/bs.acdb.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, E. J. , & Douglas, L. (2012). Assessing the key processes of youth‐led participatory research. Youth & Society, 47(1), 29–50. 10.1177/0044118X12468011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, L. (2015). Decolonizing educational research: From ownership to answerability. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perry‐Hazan, L. (2016). Children's participation in national policymaking: “you're so adorable, adorable, adorable! I'm speechless; so much fun!”. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, T. , Kas‐Osoka, C. , & Mizell, J. D. (2021). Co‐Constructing knowledge: critical reflections from facilitators engaging in youth participatory action research in an after‐school program. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 17(2), n2. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1342478 [Google Scholar]

- Ritterbusch, A. (2012). Bridging guidelines and practice: Toward a grounded care ethics in youth participatory action research. The Professional Geographer, 64(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sabati, S. (2019). Upholding “colonial unknowing” through the IRB: Reframing institutional research ethics. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(9–10), 1056–1064. 10.1177/1077800418787214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnarch, B. (2004). Ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) or self‐determination applied to research: A critical analysis of contemporary first nations research and some options for first nations communities. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 1, 80–95. 10.18357/IJIH11200412290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seminole Tribe of Florida . (n.d.). History: Where we came from . https://www.semtribe.com/history/introduction

- Shore, N. (2007). Community‐based participatory research and the ethics review process. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2(1), 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. M. , & Gatas, L. (2021). Here to stay: How we created a movement toward decolonizing our high school. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 12(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, A. , Ballard, P. J. , Hoyt, L. T. , & Ozer, E. J. (2021). Applying a developmental lens to youth‐led participatory action research: A critical examination and integration of existing evidence. Youth & Society, 53(1), 26–53. 10.1177/0044118X1983787 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, S. , Augsberger, A. , Richards‐Schuster, K. , & Sprague Martinez, L. (2021). Participatory research approaches with youth: Ethics, engagement, and meaningful action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(1–2), 142–153. 10.1002/ajcp.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag . (n.d.). The History of the Neponset Band of the Indigenous Massachusett Tribe . http://massachusetttribe.org/the-history-of-the-neponset

- Toraif, N. , Augsberger, A. , Young, A. , Murillo, H. , Bautista, R. , Garcia, S. , Sprague Martinez, L. , & Gergen Barnett, K. (2021). How to be an antiracist: Youth of color's critical perspectives on antiracism in a youth participatory action research context. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(5), 467–500. 10.1177/07435584211028224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tri‐Council of Canada .1998. Canada's Tri‐Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans . https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/documents/tcps2-2018-en-interactive-final.pdf

- Wampanoag Tribe . (n.d.). Wampanoag history. https://wampanoagtribe-nsn.gov

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.