Abstract

Introduction

Critical theories, such as Critical Race Theory, are a group of theories developed to explicate structural, historical, and social issues that perpetuate inequities and might inform institutional efforts. This study reviewed critical theory use in health professions education with the primary objectives of understanding how and to what extent these theories have been applied.

Methods

A rapid review was performed in October 2021 with four electronic databases. Scholarship was screened with Covidence based on inclusion (critical theory and health professions education) and exclusion (gray literature, not written in English, not critical theory, not education setting, not peer reviewed) criteria. Data were extracted, charted, and analyzed by three reviewers through Excel, with findings reviewed by the entire research team.

Results

A total of 154 pieces of scholarship were included. Most scholarship emerged between 2010 and 2019 (n = 69, 44.8%) and nursing (n = 93, 54.4%) was most represented. Scholars were most frequently from the United States (n = 62, 35.6%), used theoretical methodologies (n = 84, 50.3%), and leveraged Critical & Critical Social Theory (n = 67, 30.7%). In scholarship with major theory use (n = 52, 33.8%), scholars also most commonly used Critical Theory & Critical Social Theory (n = 25, 34.2%).

Conclusions

This review exposed gaps in the use of critical theory in health professions education. Scholars should consider expanding the application of critical theories, additional research methodologies, and aspects of education that were largely absent. Expanding critical theory to further explicate aspects of training programs and institutions could deepen our understanding of the mechanisms impacting student development and success in health professions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-06979-1.

Keywords: Critical theory, Critical social theory, Health professions education, Rapid review, Theory talk

Introduction

Health professions education aims to equip learners with the knowledge and skills needed to serve our communities and champion the well-being of others. However, various structural and social barriers have limited the accessibility and effectiveness of this training [1]. Research suggests, for example, that curricula often lack marginalized perspectives, creating barriers for individuals of color [2] and that educators tend to describe patient differences through genetic lenses as opposed to power, environmental, or social perspectives; [3] issues with assessment (e.g., competency based exams) in medical education are also well-documented regarding equity gaps [4–6]. These complex problems require rich theoretical perspectives to advance our understanding and inform solutions [7].

Critical theories, a group of theories specifically developed to explicate structural, historical, and social issues that perpetuate inequities, may serve as a remedy to improve health professions education [8]. They include (but are not limited to) Feminist Theory, Queer Theory, and Critical Race Theory (CRT). In contrast to theories that aim to understand or explain society, critical theories focus on liberation and power differentials, helping us to understand and overcome socially constructed barriers. The origins trace back to the 1930s, or even earlier to Kant’s works, with the “Frankfurt School” (Frankfurt Institute for Social Research) where philosophers such as Horkheimer coined the moniker “critical theory” to challenge, comprehend, and critique societal issues at the time [9]. Although critical theory has existed for approximately 100 years [9–12], it was popularized in the field of education through Freire’s 1970 book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [13] Freire advocated for humanizing education, in which students are co-creators of knowledge, and described the potential role of education in liberating the oppressed [13]. This idea of critical pedagogy has been used to examine various aspects of higher education, including assessment [14], entrepreneurialism [15], and academic freedom [16].

Critical theories first appeared in health professions education in the 1990s [17–20]. However, the extent to which these theories have been engrained and applied to health professions education remains unclear. The purpose of this review was to interrogate the use of critical theories in health sciences education with the primary aim of understanding how and to what extent they have been applied to better guide scholarship in our profession. We believe this work is timely and necessary for extending our understanding of critical barriers within health professions education and advancing our use of theory in educational research.

Three research questions were used to guide our review: (1) What patterns exist among health professions education scholarship that used critical theories to explore education, (2) How do health professions education scholars apply critical theories to explore education, and (3) What patterns exist of health professions education scholars who majorly applied critical theories to explore education? These questions seek to address gaps in our understanding of the evolution of critical theory in health professions education scholarship over time, the extent to which scholars apply critical theories aiming to improve health professions education, and the patterns in which scholars use critical theories that may in turn inform future use. The term education scholar(ship) is utilized to broadly encompass various types of disciplines, authors, and methodologies.

Methods

Study design

Rapid reviews simplify parts of systematic reviews to quickly and rigorously produce information [21, 22]. While there is a lack of consistency in elements of rapid reviews [21], our paper followed common components, including developing a research aim, using a protocol (PRISMA-ScR), literature search, screening and study selection with minimum of two reviewers, partaking in data extraction, quality assessment, and a descriptive synthesis of results [21–25]. Given the rapid nature, we omitted a web protocol and external peer data review [23].

Literature search strategy

After consultation with a librarian, four databases were searched (ERIC, PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase & Medline via Embase; Embase Classic was not used directly) using 491 terms since 1970 related to any health professions education (e.g., nursing, dentistry, medicine) and any critical theories (e.g., Feminist Theory, CRT), omitting language (e.g., diversity, equity) outside the scope of critical research (Appendix A). The terms and start year were selected to align to medical education and critical theory broadly based on preliminary literature evaluation [9–13], the scope of the research questions, and when educational research began incorporating critical theory, demonstrated in Freire’s work [13]. In October 2021, three reviewers conducted the search, screening, and data extraction.

Study selection criteria and assessment

Scholarship was included if it came from peer-reviewed journals, used the term critical theory or a related sub-theory, and addressed the topic of health professions education [26]. Scholarship was excluded if it was not about health professions education or not the correct setting (e.g., lab-based studies), not using critical theory, were gray-literature (e.g., not indexed) or not published in journals (e.g., dissertations/theses, conference proceedings, books), or were not written in English. After removing duplicates and initial automatic ineligibles, abstracts were reviewed to determine if they should advance to full-text screening. Screening was completed iteratively in Covidence [27] with team check-ins throughout the review process. The reviewers charted 10% of scholarship together at each phase (abstract review, full text review, and data extraction) to assure consistency and quality, reaching 80%+ intercoder agreement for eligibility, resolving any disagreements, and achieving consensus; the remaining scholarship was split individually among the reviewers.

Data extraction & analysis

Data extraction was managed in a charting file created with Microsoft Excel. The tool was piloted with ten pieces of scholarship and adjusted to extract the categories: publication year, health profession discipline(s), research methodology, scholar country as determined by all university affiliations when listed, theory(ies) used, and theory talk (assessing the quality of theory application). The level of theory talk was evaluated using and adapting a version of Kumasi and colleagues’ Theory Talk Framework [28]; scholarship was characterized as minimal theory talk if they used or named a critical theory but did not discuss it in depth; moderate theory talk if they related a critical theory to health professions education yet did not conduct research; and major theory talk if they threaded a critical theory throughout a research study, leading to new insights, theories, or contributions to the field [28, 29] Scholars have previously used the theory talk framework to characterize theory use (e.g., Cognitive Apprenticeship) in health professions education research [29, 30].

Results

Article selection

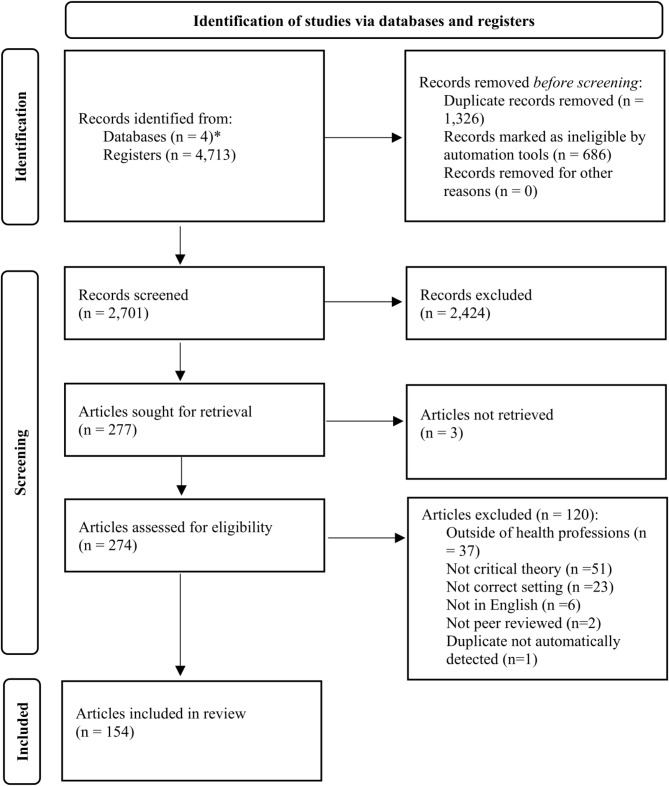

Our search yielded 2,701 abstracts after automatically marking records as excluded and removing duplicates (Fig. 1). Abstract screening resulted in 277 pieces of scholarship that were advanced to full-text screening; of those, 154 pieces met the inclusion criteria for full review and 52 were coded as major theory talk (Appendix B).

Fig. 1.

Review procedure. *Databases: Embase & Medline via Embase (n = 892), ERIC (n = 791), PubMed (n = 1,291), PsycInfo (n = 1,053)

Descriptive synthesis of scholarship

Six extraction categories applied to the papers helped answer our research questions (Table 1). For brevity, we present the most and least frequent characteristics within the categories.

Table 1.

Summary Characteristics of Critical Theory Articles in Health Professions Education (N = 154)

| Category | Characteristic | Total n (%) | Major n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theory Talk | Major | 52 (33.8) | 52(100) |

| Moderate | 79 (51.3) | ||

| Minor | 23 (14.9) | ||

| Year | 1980–1989 | 1 (0.6) | |

| 1990–1999 | 29 (18.8) | 3 (5.8) | |

| 2000–2009 | 19 (12.3) | 6 (11.5) | |

| 2010–2019 | 69 (44.8) | 30 (57.7) | |

| 2020–2021 | 36 (23.4) | 13 (25.0) | |

| Discipline | Dentistry | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.8) |

| Medicine | 47 (27.5) | 20 (35.7) | |

| Midwifery | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Nursing | 93 (54.4) | 29 (51.8) | |

| Other (e.g., African American Studies, Biostatistics) | 26 (15.2) | 6 (10.7) | |

| Pharmacy | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Method | Historical | 1 (0.6) | |

| Mixed | 8 (4.8) | 4 (7.5) | |

| Other (e.g., case, commentary) | 9 (5.5) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Qualitative (e.g., interviews) | 53 (32.1) | 35 (66.0) | |

| Quantitative | 2 (1.2) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Review (e.g., systematic) | 9 (5.5) | 4 (7.5) | |

| Theoretical (e.g., theory building or critique) | 84 (50.3) | 7 (13.2) | |

| Country | Australia | 18 (10.3) | 10 (14.1) |

| Canada | 45 (25.9) | 15 (21.1) | |

| Europe | 32 (18.4) | 16 (22.5) | |

| Other (e.g., China) | 17 (9.8) | 11 (15.5) | |

| United States | 62 (35.6) | 19 (26.8) | |

| Theory | Critical Consciousness | 10 (4.6) | 4 (5.5) |

| Critical Race Theory | 23 (10.6) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Critical Theory & Critical Social Theory | 67 (30.7) | 25 (34.2) | |

| Critical, Emancipatory, & Antiracist Pedagogy | 35 (16.1) | 11 (15.1) | |

| Feminist Theory (e.g., Black Feminist Thought) | 32 (14.7) | 8 (11.0) | |

| Other Critical Theory (e.g., Queer Theory) | 13 (6.0) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Other Theory & Paradigms (e.g., Constructivism) | 22 (10.1) | 10 (13.7) | |

| Post- & De-colonial Theory | 16 (7.3) | 5 (6.8) |

-Total consists of minor, moderate, and major theory talk papers. -Major calculations are a proportion of the total papers per characteristic. -An article may include multiple characteristics; totals may exceed N and 100% due to rounding

Regarding year of publication, we observed most scholarship was published between 2010 and 2019 (n = 69, 44.8%) with less published 1980–1989 (n = 1, 0.6%). Scholarship tended to originate within nursing (n = 93, 54.4%) while less common in Midwifery (n = 1, 0.6%). Scholars most frequently used theoretical methods (e.g., theory building or critique) (n = 84, 50.3%) and least frequently historical methods (n = 1, 0.6%) in their scholarship. Scholars produced the most scholarship in the United States (n = 62, 35.6%) compared to countries categories as Other (n = 17, 9.8%). Of all the theories used, the most common mentioned included Critical Theory & Critical Social Theory (n = 67, 30.7%) while less frequently we observed Critical Consciousness (n = 10, 4.6%). Most scholars employed moderate theory talk (n = 79, 51.3%) in their scholarship, where critical theories were used but not implemented with traditional research; minor theory talk (n = 23, 14.9%) papers were least common with authors often naming a critical theories without revisiting it throughout the work.

In considering major theory talk papers (n = 52, 33.8%), patterns were observed within the various extraction categories (Table 1). Major theory talk scholarship most frequently appeared in 2010–2019 (n = 30, 57.7%) with none emerging in 1980–1989. Most scholarship came from nursing (n = 29, 51.8%) with none located within pharmacy or midwifery. Scholarship most frequently used qualitative methods (n = 35, 66.0%) with none appearing to use historical approaches. The scholarship was primarily authored United States (n = 19, 26.8%) scholars and least frequently authored by scholars from Australia (n = 10, 14.1%). Scholars focused the most on Critical Theory & Critical Social Theory (n = 25, 34.2%) while using Critical Consciousness (n = 4, 5.5%) the least.

Discussion

Critical theories provide a unique lens for exploring and understanding structural, historical, and social influences in education. Our findings revealed limited, yet wide ranging and increasing use of these theories in health professions education with applications of various critical theories to multiple aspects of health professions schools and training programs. Most scholars moderately applied critical theories to their scholarship, exploring health professions education without conducting research; scholars less commonly used critical theories majorly, implementing the theory throughout the entire paper and conducting original research. While this review provides a first step toward understanding how scholars have used critical theories at the time of this inquiry, many questions and opportunities remain.

Varied use of critical theory in health professions education

The results of this review revealed considerable variability in discipline-based uptake of critical theories, suggesting that some professions may be more comfortable or equipped to engage in critical discourse. While a variety of professions were represented in the review, their proportional representation varied significantly, with nursing appearing most frequently and other professions limited or missing completely, particularly in applying critical theories majorly. Nursing’s professional and ethical frameworks, such as the American Nurses Association (2015) Code of Ethics for Nurses, focus on social justice advocacy as an ethical standard of practice [31]. Beginning in the 1970s, there was a renewed focus on critical perspectives as emancipatory knowing is a focus in nursing [32]. In addition, Boyer’s (1990) expanded view of scholarship advanced the scholarship of teaching and the use of theory-driven pedagogies in nursing; this has empowered educators to challenge existing practices and embrace critical perspectives for educating nurses [33]. Possible reasons for the absence of critical theories in other disciplines warrants further research. Although, there are several plausible explanations for the general dearth of critical theory use.

Health professions education scholarship has tended to take a more pragmatic and applied approach, with the limited use of theory [34–37]. This concern is supported by several scholars in this review, who have noted the limited application of critical theories for unpacking inequalities despite widespread emphasis on DEI across the health professions [2, 37, 38]. Further, Albert and colleagues found that health profession education scholars are more likely to draw on research from health and clinical fields than from sociology and other social sciences [35]. This siloed approach may reduce awareness of and comfort with critical theories [36]. Additionally, the focus on cultural competency and shifts to competency-based education models may prioritize skill development and practice models, leaving less room for curriculum discussion and grounding in critical theories [38–40]. While learning about culturally competent care can improve student engagement with clients from marginalized groups, this approach can also be reductionist in nature, with limited emphasis on structural inequalities and potentially reinforcing stereotypes [41–44].

Limited application of critical theory

The limited application of critical theories in health professions educators’ scholarship used in major ways may be related to bias and stigma attached to terms like feminist and queer and the underrepresentation of historically marginalized groups, particularly in leadership positions. The lack of explicit use of or identification with feminism and other critical theories has been attributed, in part, to fears that such identification could negatively impact career trajectories [37, 45]. Moreover, the underrepresentation of women, people of color, and other minoritized groups in leadership positions, including editorial and grant review boards, can unintentionally reinforce the norms and values of dominant groups in the review process [46]. This publication bias may be further exasperated when health profession educators censor the language and theories they use to publish their work [37, 46, 47].

Patterns in major theory talk scholarship

Major theory talk scholarship most frequently leveraged qualitative methods. This may not be surprising provided the health professions are largely grounded in positivist traditions, which favor quantitative research methods that are experimental and quasi-experimental in nature. The disconnect in which few reviewed pieces of scholarship exclusively used quantitative methods was apparent in our review; this lack of research was particularly surprising, given the emphasis on DEI and social determinants of health within the health professions as well as efforts within education to advance critical theories in quantitative research (e.g., Quantitative Critical Methods– “QuantCrit”) [48]. It raises questions about how quantitative research might benefit from critical theory, such as improving decision making about health professions education curricula. We also observed that major theory scholarship tended to be published more recently compared to the total corpus of papers; thus, we may be seeing a shift in methodological training and expansion of critical theory, encouraging scholars to use these approaches more fully.

Future directions & implications

Our review focused on critical theory’s application by a scholar, or at the individual level. We observed scholarship that embedded critical theory throughout introductions, methods, results, and discussions to generate new ideas. Yet, we wonder, what might higher education institutions and organizations do to further apply critical approaches in major ways [49]? Schools could center their missions or curricula around critical theory to avoid creating checklists of cultural competency courses or initiatives [50]. By underscoring theory in every aspect of an institution’s work, a shift might occur yielding not only more access to, and equity for, culturally-relevant health professions education, but access to, and equity within, health professions education in general. Given the influence of accreditors and academies on admissions, curricular content, and requirements for learners (e.g., American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Association of American Medical Colleges) [51–53], we also wondered about their potential role in the use of critical theories for advancing health professions education. Agencies that accredit nursing education programs, for example, seek to improve public health by ensuring the delivery of quality curricula that prepare nurses to provide care that meets societal and health care trends [54], and include professional competencies related to compassionate care, DEI, and social determinants of health [55]. Exploring the power of how accreditors or licensing bodies steer scholars and disciplines - either toward maintaining the status quo or challenging them to deeply ideate and iterate about ways to improve DEI– could be an important next step toward understanding the uptake of critical theory.

Addressing challenges in health professions education using critical perspectives could increase access to our programs, prepare a healthcare workforce that can address existing barriers in healthcare, and advance the scholarship of teaching and learning specific to critical theory. For example, asking critical questions about admission criteria could improve student selection practices, which can result in a workforce reflective of the communities being served. Using critical theory within and across curricula can equip students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to ask critical questions, engage in reflective practice to understand disadvantage and injustice in health care, and make decisions that improve healthcare processes and outcomes [56, 57].

Based on the results of this review, we hope to see increasing use of critical theories and emerging related theories [58], such as anti-oppressive theory and practice (AOP) throughout scholarship. Developed within the field of social work, AOP is an approach to practice that draws on critical, feminist, and other postmodern theories to focus attention on the processes and outcomes of working with service users to identify and dismantle oppressive systems [59]. Indeed, research informed by AOP includes minoritized populations in the research process to center participants’ identities, disrupt the perpetuation of stereotypes, and support knowledge development aimed at removing societal barriers [59]. As health professions education evolves, we must draw from AOP and other critical theories to better understand and teach how clinical experiences are shaped by larger systems and structural inequalities [2, 36].

Limitations

First, it is possible that other terminology (e.g., critical theorists or additional critical theories) might have yielded additional scholarship; however, we believe our search strategy yielded a full corpus of relevant studies [25]. Second, the gamut of scholarship covered made it challenging to succinctly summarize and report all the nuances of critical theory as well as the evolving contexts in which health professions educators use it [25]; however, we believe the frameworks used to guide this review (i.e., Theory Talk) helped situate and organize the findings appropriately. Third, we did not evaluate the quality of the methods or research designs within scholarship in this review given our focus on the application of critical theory. Finally, we recognize our positions and identities in the academy situated us to observe the literature from a specific perspective, representing a fraction of all social identities and health professions.

Conclusion

This review exposed noteworthy gaps in the use of critical theories in health professions education, revealing opportunities for expanded application of various critical theories, use of additional research methodologies, and focus on aspects of education that were largely absent. Expanding critical theory to further explicate critical aspects of our training programs and institutions could deepen our understanding of social injustices and the mechanisms impacting student development and success in the health professions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Rebecca Carlson for her contribution to the literature search.

Author contributions

KF made substantial contributions to the design of the work, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. AS and EG contributed to the design of the work, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. SM contributed to analysis of the data, and writing of the manuscript. JM made substantial contributions to the design of the work, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The authors conducted the research ethically; IRB approval was not needed given the methodology.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Draper JK, Feltner C, Vander Schaaf EB. Preparing medical students to address health disparities through longitudinally integrated social justice curricula: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt TR, Rockich-Winston N, White D, Taylor TR. Changing the narrative: a study on professional identity formation among Black/African American physicians in the US. Adv Health Sci Edu. 2021;26(1):183–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olafuyi O, Parekh N, Wright J, Koenig J. Inter-ethnic differences in pharmacokinetics—is there more that unites than divides? Pharmacol Res Persp. 2021;9(6):e00890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffield KE, Spencer JA. A survey of medical students’ views about the purposes and fairness of assessment. Med Ed. 2002;36(9):879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memon MA, Joughin GR, Memon B. Oral assessment and postgraduate medical examinations: Establishing conditions for validity, reliability and fairness. Adv Health Sci Ed. 2010;15(2):277–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colbert CY, French JC, Herring ME, Dannefer EF. Fairness: the hidden challenge for competency-based postgraduate medical education programs. Persp Med Ed. 2017;6(5):347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell B. Social justice and sociological theory. Society. 2021;58(5):355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradis E, Nimmon L, Wondimagegn D, Whitehead CR. Critical theory: broadening our thinking to explore the structural factors at play in health professions education, Aca Med: 2020;95(6):842–845. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bronner SE. Of critical theory and its theorists. Volume 11. Routledge 2013.

- 10.Crenshaw KW, Race R. Retrenchment: transformation and legitimation in antidiscrimination law. Harv L Rev. 1988;1331:1332. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devetak R. Critical theory. In: Burchill S, Linklater A, Devetak R, et al. editors. Theories of international relations. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. 2005;137–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horkheimer M. Critical theory: selected essays. A&C Black. 1972.

- 13.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. Bergman Ramos, trans). New York: Continuum. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serrano MM, O’Brien M, Roberts K, Whyte D. Critical pedagogy and assessment in higher education: the ideal of ‘authenticity’ in learning. Act Learn High Edu. 2018;19(1):9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert C, Parker A, Neary M. Entrepreneurialism and critical pedagogy: reinventing the higher education curriculum. Teach High Edu. 2007;12(4):525–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giroux HA. Academic freedom under fire: the case for critical pedagogy. Coll Lit. 2006;1:1–42.

- 17.Bent KN. Perspectives on critical and feminist theory in developing nursing praxis. J Prof Nurs. 1993;9(5):296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grams KM, Christ MA. Faculty work load formulas in nursing education: A critical theory perspective. J Profes Nurs. 1992;8(2):96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton JA. Feminist theory and health psychology: tools for an egalitarian, woman-centered approach to women’s health. J Women’s Health. 1993;2(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrich KT, Witt B. The passionate connection: feminism invigorates the teaching of nursing. Nurs Outlook. 1993;41(3):117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, Perrier L, Hutton B, Moher D, Straus SE. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King VJ, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Kamel C, Garritty C. Paper 2: performing rapid reviews. Syst Reviews. 2022;11(1):151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inform Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tricco AC. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Durning SJ, Young ME. Knowledge syntheses in medical education: demystifying scoping reviews. Acad Med. 2017;92(2):161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training. World Health Organization Guidelines 2013. 2013. [PubMed]

- 27.Covidence. Better systematic review management. Accessed 2022 May 12. https://www.covidence.org/

- 28.Kumasi KD, Charbonneau DH, Walster D. Theory talk in the library science scholarly literature: an exploratory analysis. Lib Info Sci Re. 2013;35(3):175–80. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyons K, McLaughlin JE, Khanova J, Roth MT. Cognitive apprenticeship in health sciences education: a qualitative review. Adv Health Sci Ed. 2017;22(3):723–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin JE, Wolcott MD, Hubbard D, Umstead K, Rider TR. A qualitative review of the design thinking framework in health professions education. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Nurses Association. Code of ethics for nurses. American Nurses Publishing. 2015.

- 32.Chinn PL, Kramer MK. Knowledge development in nursing. Theory and process. 10th ed. Elsevier. 2018.

- 33.Boyer EL. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, N.J: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert M, Hodges B, Regehr G. Research in medical education: balancing service and science. Adv Health Sc Educ. 2007;12(1):103–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert M, Rowland P, Friesen F, Laberge S. Interdisciplinarity in medical education research: myth and reality. Adv Health Sc Educ. 2020;25(5):1243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chow CJ, Hirshfield LE, Wyatt TR. Sharpening our tools: conducting medical education research using critical theory. Teach Learn Med. 2022;34(3):285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma M. Applying feminist theory to medical education. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):570–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandars JE. Critical theory and the scholarship of medical education. Intl J Med Educ. 2016;7:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurley D, Taiwo A. Critical social work and competency practice: A proposal to Bridge theory and practice in the classroom. Social Work Edu. 2019;38(2):198–211. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrums ME, Leppa C. Beyond cultural competence: teaching about race, gender, class, and sexual orientation. J Nurs Educ. 2001;40(6):270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger JT, Miller DR. Health disparities, systemic racism, and failures of cultural competence. Am J Bioeth. 2021;21(9):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine SJ, Reid P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Intl J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irvine JM. Is sexuality research ‘dirty work’? Institutionalized stigma in the production of sexual knowledge. Sexualities. 2014;17(5–6):632–56. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keir M, McFadden C, Ruzycki S, Weeks S, Slawnych M, McClure RS, Kuriachan V, Fedak P, Morillo C. Lack of equity in the cardiology physician workforce: a narrative review and analysis of the literature. CJC Open. 2021;3(12):S180–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Finn GM, Brown ME. Ova-looking feminist theory: a call for consideration within health professions education and research. Adv Health Sci Educ 2022;1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Gillborn D, Warmington P, Demack S, QuantCrit. Education, policy big data and principles for a critical race theory of statistics. Race Ethn Educ. 2018;21(2):158–79. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donetto S. Medical students and patient-centred clinical practice: the case for more critical work in medical schools. Br J Soc Educ. 2012;33(3):431–49. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grenier ML. Cultural competency and the reproduction of white supremacy in occupational therapy education. Health Educ J. 2020;79(6):633–44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti-racism. Accessed 11. May 2022. https://www.aacp.org/deia

- 52.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Who we are. Accessed 6 Jun 20222. https://www.aacnnursing.org/About-AACN

- 53.Association of American Medical Colleges. Equity, diversity, & inclusion. Accessed 6 June 2022. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion

- 54.National League for Nursing Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation (NLN CNEA). Accreditation standards for nursing education programs. 2021.

- 55.American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). The essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education. 2021.

- 56.Delany C, Watkin D. A study of critical reflection in health professional education: ‘learning where others are coming from’. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(3):411–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pert J, MacKinnon K. Cultivating praxis through Chinn and Kramer’s emancipatory knowing. Adv Nurs Sci. 2018;41(4):352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adam S, Juergensen L. Toward critical thinking as a virtue: the case of mental health nursing education. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;38:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sellon AM, Lassman H. Anti-oppressive theory and practice. In: Bolton KW, Hall JC, Lehmann P, editors. Theoretical perspectives for direct social work practice. 4 ed. New York NY: Springer. 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.