Abstract

The majority of drugs target membrane proteins, and many of these proteins contain ligand binding sites embedded within the lipid bilayer. However, targeting these therapeutically relevant sites is hindered by limited characterization of both the sites and the molecules that bind to them. Here, we introduce the Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB), a curated dataset of 413 structures of ligands bound at the protein-bilayer interface. Analysis of these structures reveals that ligands binding to lipid-exposed sites exhibit distinct chemical properties, such as higher calculated partition coefficient (clogP), molecular weight, and a greater number of halogen atoms, compared to ligands that bind to soluble proteins. Additionally, we demonstrate that the atomic properties of these ligands vary significantly depending on their depth within and exposure to the lipid bilayer. We also find that ligand binding sites exposed to the bilayer have distinct amino acid compositions compared to other protein regions, which may aid in the identification of lipid-exposed binding sites. This analysis provides valuable guidelines for researchers pursuing structure-based drug discovery targeting underexploited ligand binding sites at the protein-lipid bilayer interface.

Subject terms: Membranes, Molecular modelling, Target identification, Biophysical chemistry, Cheminformatics

Targeting membrane proteins at sites embedded in the lipid bilayer offers the potential to discover ligands for undruggable targets; however, ligand binding at the protein-membrane interface remains underexplored. Here, the authors introduce the Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB), a curated dataset of 413 structures of ligands bound at the protein-bilayer interface, identifying that lipid-exposed small molecules have distinct chemical properties that depend on their position in the bilayer and demonstrating the distinct amino acid compositions of these lipid-exposed binding sites.

Introduction

Targeting membrane proteins at sites embedded in the lipid bilayer is an underexplored approach with significant potential for discovering novel ligands and targeting binding sites that are typically considered “undruggable”1. The majority of small-molecule drug targets are membrane proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, membrane-bound enzymes, and antibiotic protein targets2. Drug discovery efforts often focus on targeting protein domains exposed to the aqueous environment, leading to the development of small-molecule modulators that bind to water-solvated pockets. However, many membrane proteins have functional ligand binding sites embedded in the plasma membrane at the protein-lipid interface3–5. Traditional drug discovery efforts have targeted cytosolic or extracellular orthosteric sites, the primary binding pockets for endogenous ligands6. However, the high sequence and structural conservation of orthosteric sites within protein families often hinder ligand specificity for a single subtype7. By targeting allosteric binding sites, such as those facing the lipid bilayer, differences in structure between receptor subtypes can be exploited to design selective ligands4,8,9. For example, the development of drugs targeting cannabinoid receptors is challenging due to the high conservation of their orthosteric binding sites10. However, a subtype-specific modulator of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) that exhibits its preferential binding to the CB1 protein by binding at the protein-bilayer interface was discovered11,12.

The lipid bilayer-protein interface presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities for drug design. Phospholipids, the primary components of the bilayer, are composed of a hydrophilic head group and two hydrophobic tails. The charged or zwitterionic head groups are exposed to the aqueous environment on either side of the membrane, and the hydrophobic tails form the core of the bilayer. The arrangement of these lipids creates an interfacial region with varying polarity, charge, and mass density depending on the depth within the bilayer13–15. This heterogeneity influences the orientation of ligands relative to the membrane16–19. For example, molecules in the bilayer may orient more polar or charged groups towards the lipid head groups or glycerol backbones, and more nonpolar groups towards the acyl tails, to maximize favorable interactions with the membrane environment. Additionally, the low dielectric constant of the lipid bilayer impacts electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and ionic interactions between drug molecules and their target proteins. These distinct environmental features can be exploited to guide the design of drugs which selectively bind to the protein-bilayer interface3.

The differences between the physicochemical features of the membrane versus aqueous environments also influence large structural differences between membrane-embedded and soluble proteins. While soluble proteins display diverse secondary structure features, membrane proteins are predominantly composed of a-helices that span the lipid bilayer20. Furthermore, membrane proteins exhibit a distinct distribution of hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues. Hydrophobic amino acids are typically exposed to the membrane and hydrophilic residues are typically oriented towards the protein interior or aqueous surfaces21. Consequently, drug design strategies targeting the protein–lipid interface must leverage interactions with hydrophobic residues to achieve binding affinity and selectivity.

Partitioning between the aqueous and lipidic environments and engaging a binding site at the protein-membrane interface requires a driving force. This driving force may arise either from physicochemical properties intrinsic to the molecule, such as sufficient lipophilicity and low net charge, or the assistance of the protein to which the ligand binds18,22.

Advances in structural biology have led to the availability of hundreds of high-quality structures of ligands bound at the protein-bilayer interface. Here, we report the results of a quantitative analysis of these ligands and their binding modes to establish a framework for understanding ligand interactions within the lipid-facing environment. By systematically examining these structures, we aim to provide insight into the rational design of molecules targeting these often-overlooked binding sites.

Results and discussion

The lipid bilayer impacts thermodynamics of ligand binding

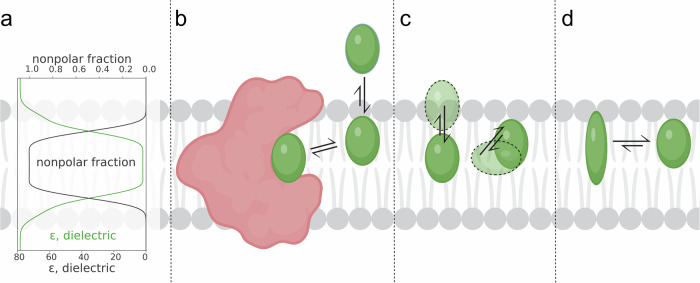

The lipid bilayer is an anisotropic solvent with varying dielectric constant, hydrogen bond donating and accepting capacity, density, and chemical composition with respect to the normal of the bilayer (Fig. 1a)13–15. The lipid bilayer influences the thermodynamics of ligand binding through its effects on ligand partitioning23,24 (Fig. 1b), positioning19,25–28 (Fig. 1c), and conformation17,18,29,30 (Fig. 1d) within the membrane. These variations affect the depth, orientation, and conformational preferences of molecules embedded within the membrane, ultimately influencing binding kinetics and affinities for ligands which bind at the protein-bilayer interface31.

Fig. 1. Thermodynamic considerations for ligand binding at the protein-lipid interface.

a Dielectric and nonpolar fraction with respect to depth in a lipid bilayer. Qualitative reproduction of data from15. b Ligand partitioning into the bilayer localizing near its target. c Ligand oriented at a preferred depth and orientation in the bilayer. d Ligand preferentially adopting a specific conformation in the lipid environment.

The partitioning of small molecules into lipid bilayers impacts their binding kinetics through multiple mechanisms. Ligand binding to a membrane-associated pocket can be thought of as a two-step process: first the ligand partitions into the bilayer, then it binds to its target (Fig. 1b). Sufficiently lipophilic ligands can accumulate in the bilayer, enhancing their apparent affinity by raising their local concentration around the target membrane protein23,24. Additionally, while in the membrane phase, a ligand can only diffuse laterally, and therefore is mostly limited to two translational degrees of freedom parallel to the membrane plane32.

Furthermore, ligands may preferentially locate to specific depths in the bilayer normal, facilitating binding to membrane-exposed sites at corresponding depths19,25–28 (Fig. 1c). For instance, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of general anesthetic desflurane and its target, the G. violaceus ligand-gated ion channel, demonstrate that the ligand reaches a depth in the bilayer that corresponds with the depth of its binding site on the protein28. There is also evidence that some molecules may have a preferred orientation with respect to the lipid bilayer. Guo et al. used MD simulations and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) with magnetically aligned bicelles to demonstrate that different cannabinoids align with preferred orientations relative to the bilayer33.

Furthermore, some molecules may preferentially adopt specific conformations in the lipid bilayer; for example, burying polar groups in themselves (Fig. 1d)17,18,29,30. This reduces the internal degrees of freedom of the unbound ligand which may decrease the entropic cost of a ligand binding to its target. Such molecules have been termed “molecular chameleons” for their ability to shield or expose polar groups depending on their solvent30. For instance, Valsartan, an antihypertensive drug, has been shown to adopt different conformations based on its solvent. In the lipid bilayer, a conformation that favors binding to the angiotensin II receptor type 1 is stabilized, promoting its interaction with a lipid-exposed binding site34,35. Additionally, MD simulations of BPTU binding to the P2Y purinoceptor 1 at a membrane exposed binding site show that the ligand preferentially locates at depth in the bilayer near its binding site. The simulations also show that the internal degrees of freedom of the ligand are reduced in the lipid environment, making it more likely to interact with the protein in its preferred binding conformation18. Furthermore, structural studies have shown that some ligands which bind at the protein-bilayer interface, such as cystic fibrosis drug Ivacaftor36 and antifungal drug Posaconazole37, form intramolecular hydrogen bonds in their protein-bound poses which shield polarity in lipid tail exposed regions. However, more extensive work would need to be done to characterize the role of the solvent in stabilizing the compounds’ binding poses. Despite these observations, the influence of the lipid bilayer on ligand conformation remains an underexplored area of study, particularly with respect to how it impacts the entropy of ligands binding to membrane exposed protein sites38.

Knowledge of the preferred depth, orientation, and conformation of a molecule in the bilayer can aid in targeting a membrane exposed site for structure-based drug discovery. The preferred depth of a molecule in the bilayer can be determined experimentally with methods such as fluorescence quenching39, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR), wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), or neutron diffraction26,40. However, these experiments are not high-throughput and the results may be qualitative or semi-qualitative. Additionally, computational methods, such as free energy calculations using MD simulations17,41,42, can be a more high-throughput approach to determining a molecule’s preferred depth or orientation in the bilayer. However, even the throughput of MD simulations can vary significantly depending on the level of accuracy required, the size of the system, and the computational resources available. Other computational models which leverage implicit solvents such as COSMOmic43 or those calibrated against experimental data26, can provide faster, approximate depth estimates suitable for larger-scale screenings. Additionally, the Molecules on Membranes Database (MolMeDB)44 provides precalculated preferred locations and curated experimental data for some molecules.

Methods such as NMR45,46 or MD simulations17,41 can be applied to characterize the conformational preference in both water and lipidic medium for molecules that are being developed to bind to lipid-exposed binding sites. However, there are relatively few high-throughput and validated models available to determine how a molecule’s preferred conformation varies depending on its depth within the bilayer, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB): a diverse dataset of ligands bound to the protein bilayer interface

To gain insights into the structural features of ligands that bind to the protein-lipid interface, we curated a comprehensive dataset, the Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB), containing 412 high-quality protein complexes with druglike molecules bound at the protein–lipid interface. LILAC-DB contains 231 unique small molecules interacting with 175 proteins, providing a diverse representation of ligand–protein–lipid interactions. 11% of ligands in the dataset are FDA approved drugs and 9% of the ligands are in clinical trials47. For each ligand, we annotated individual atoms as being either exposed to the lipid bilayer or buried in the protein. The proteins in the dataset comprise a variety of functional classes (Fig. 2a), including transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (Fig. 2b), cytochrome complexes (Fig. 2c), and GPCRs (Fig. 2d). The majority of proteins represented in this dataset are from animals/eukaryotes, but bacterial and plant proteins are also present (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, these proteins reside in diverse cellular compartments, such as the plasma membrane, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear envelope, and other membranes (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2. Dataset of ligands bound at the protein-lipid interface.

a Pie chart describing the functional classes of proteins represented in the dataset. b Membrane associated ligands (blue) bound to GPCRs (representative protein structure PDB ID: 4PHU88). c Membrane associated ligands (purple) bound to cytochrome complexes (representative protein structure PDB ID: 6XVF89). d Membrane associated ligands (pink) bound to transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (representative protein structure PDB ID: 5IRX90).

While there are other curated protein-ligand datasets48,49 they lack annotations regarding the location of the binding site relative to the membrane. To our knowledge, LILAC-DB is the largest curated dataset of structures of ligands bound at the protein-bilayer interface, and its structural diversity offers a valuable opportunity to analyze features of ligand binding at the protein–lipid interface. The dataset is available on the Zenodo open-access repository at https://zenodo.org/records/14835079, and a summary of the dataset can be found in Supplementary Data File 1.

Chemical properties of ligands at the protein–lipid vs. protein–water interfaces

To compare the properties of molecules binding at the protein–lipid interface to those of druglike molecules which bind to water-solvated sites, we analyzed LILAC-DB against a random selection of 10,000 bioactive druglike molecules from the ChEMBL database50 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of membrane-associated and ChEMBL ligands (mean ± standard error of the mean). Significance tested with a Mann–Whitney U test

| Property | Membrane-associated ligands | ChEMBL ligands | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hydrogen bond donors | 1.84 ± 0.13 | 2.01 ± 0.04 | 2.56e−01 |

| Number of hydrogen bond acceptors | 5.66 ± 0.22 | 5.72 ± 0.05 | 5.76e−01 |

| Molecular mass (Da) | 460.17 ± 10.75 | 436.41 ± 2.66 | 2.238e−05*** |

| cLog P | 4.37 ± 0.14 | 3.30 ± 0.03 | 2.934e−16*** |

| Number of carbon atoms | 24.16 ± 0.57 | 22.33 ± 0.12 | 4.801e−07*** |

| Number of oxygen atoms | 3.99 ± 0.22 | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 1.123e−02* |

| Number of nitrogen atoms | 2.62 ± 0.13 | 3.54 ± 0.04 | 4.336e−08*** |

| Number of halogen atoms | 1.17 ± 0.10 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 2.685e−06*** |

| Number of atoms with positive formal charge at pH 7.4 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 2.683e−02* |

| Number of atoms with negative formal charge at pH 7.4 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 8.04e−01 |

Membrane-associated ligands have similar numbers of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors compared to ChEMBL ligands (Table 1). This finding is in agreement with computational studies that have shown that these molecules can engage in hydrogen bonds with lipid head groups, a capability that can facilitate their diffusion through lipid bilayers toward binding sites buried in the membrane51.

Ligands from LILAC-DB have significantly higher molecular masses and calculated partition coefficients (clog P) compared to other druglike molecules. Larger molecules may exhibit more conformational flexibility, allowing them to shield polar groups when they are in the lipid bilayer and expose them when they are in an aqueous environment30,52. A higher clog P also suggests that ligands are more hydrophobic and have a stronger affinity for the nonpolar environment of the lipid bilayer, which enables them to partition into the bilayer and reach their binding sites.

Membrane-associated ligands also demonstrate a different elemental composition compared to other druglike molecules, with a greater number of carbons, oxygens, and halogens, and fewer nitrogens. The increased presence of carbons is reflective of the ligands’ lipophilicity and ability to engage lipid tail groups. Halogens can participate in both hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions, enhancing the ligand’s solubility and membrane permeability53, while also contributing to binding affinity through halogen bonding and van der Waals interactions with either the protein or lipids54. Among strictly polar groups, the relative abundance of oxygens over nitrogens could be associated with the reduced propensity to protonate of the former55. This would still afford the molecule the polar interactions necessary to guarantee water solubility but without the liability of producing positively charged species.

In line with this observation, there were fewer ligand atoms with positive formal charge in LILAC-DB than among the ChEMBL ligands, while rates of negative formal charge were similar. Negative formal charges (i.e. acidic groups) have been found more frequently in the polar lipid head regions where they can interact with positively charged head groups (Supplementary Fig. 1) and form neutral species. When negatively charged ligand atoms were found in the lipid tail region, they were often buried or otherwise stabilized by interaction with the protein (see Case Study 1).

When present, atoms bearing positive formal charge at physiological pH were most frequently found in the lipid tail group region of the bilayer, often exposed to the lipid tail groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Computational studies have suggested that basic groups in the lipid bilayer are not typically stabilized by deprotonation55. Other groups have proposed that ligands with basic amines may interact favorably with negative charges in lipid head groups3, however, we find relatively few examples of these interactions.

These results have implications for the design of drugs that target membrane proteins. By understanding the physicochemical properties of membrane-associated ligands, researchers can identify molecules that are more likely to effectively interact with the protein–lipid interface. For example, incorporating hydrophobic groups and halogen atoms into drug candidates can enhance their affinity for the bilayer and improve their ability to reach their target proteins. Additionally, optimizing the formal charge of drug molecules can help minimize electrostatic repulsion and improve their partitioning into the membrane.

Chemical properties of membrane-bound ligands exposed to lipid head groups, lipid tail groups, and buried in protein

We next wanted to explore how ligand properties within the set of membrane-associated ligands vary depending on solvation, so we characterized ligand atoms by their depth in the lipid bilayer and as either exposed to the lipid medium or buried in the protein.

First, lipophilicity was estimated by calculating the ligand cLog P coefficients using the Crippen method, decomposing the contribution of individual atoms. The Crippen cLog P method56 estimates the octanol–water partition coefficient (log P) of a molecule by summing the contribution assigned to each of its individual atoms. Atoms with a higher Crippen contribution are more lipophilic and atoms with a lower Crippen contribution are more hydrophilic. While atomic contributions were parameterized to recapitulate a molecular property, they retain some value in describing the local atomic environment and properties57,58. Here, we analyzed the average atomic Crippen contribution of buried and exposed ligand atoms in LILAC-DB (Fig. 3a, b). Ligand atoms were classified as buried or exposed on the criteria described in the “Dataset curation” section.

Fig. 3. Atomic properties of ligands with respect to depth in the bilayer and solvent exposure.

a Binned average of atomic Crippen contribution of exposed and buried ligand atoms with respect to the position in the lipid bilayer. The shaded region represents standard error. b Violin plots of atomic Crippen contribution of ligand atoms separated by exposure and membrane region. Means of distribution are displayed as dotted black lines. c Binned average of the magnitude of espaloma partial charge of exposed and buried ligand atoms with respect to the position in the lipid bilayer. The shaded region represents standard error. d Violin plots of magnitude of espaloma partial charge of ligand atoms separated by exposure and membrane region. Means of distribution are displayed as dotted black lines.

Our data shows that exposed ligand atoms vary in lipophilicity along the membrane normal, with more lipophilic atoms (i.e. atoms with a higher Crippen contribution) being exposed to lipid tail groups than to lipid head groups (Fig. 3a). Ligand atoms exposed to lipid tail groups are more lipophilic than ligand atoms buried in the protein in the tail group region (Fig. 3b). This suggests hydrophilic atoms are either minimized in the ligand structure in this region, or else buried against the protein. In contrast, exposed ligand atoms in the head group region are more hydrophilic than ligand atoms buried in the protein, suggesting that it is favorable for ligands to expose hydrophilic groups to the polar head groups.

Buried ligand atoms, on the other hand, show no clear correlation between lipophilicity and depth in the bilayer (Fig. 3a). This finding suggests that the environment of ligand atoms buried in the protein is defined largely by the polarity and charge of the protein, rather than depth in the bilayer.

Similarly, to analyze electrostatic interactions between ligand atoms and their solvents we calculated atomic partial charges using the espaloma method59, which is a neural network-based method for approximating partial charge. We then analyzed the variations of absolute partial charge magnitude relative to the ligand depth in the lipid bilayer (Fig. 3c, d). Atoms exposed to lipid head groups have a higher magnitude of partial charge than those exposed to lipid tails (Fig. 3c, d). This suggests that ligand atoms make favorable electrostatic interactions with polar and charged lipid head group atoms and that the higher dielectric environment of the lipid head groups has a greater capacity to stabilize ligand atoms with larger partial charges.

Conversely, atoms exposed to the lipid tail group region show a lower partial charge magnitude than those buried in transmembrane regions of the protein (Fig. 3c, d). In the lipid head group region, differences between buried and exposed atoms are within standard error, suggesting that the head group and nearby protein cavities have comparable capacity to stabilize charge.

These findings underscore the importance of considering both hydrophobicity and electrostatics in understanding ligand–protein–lipid interactions and provide valuable insights to guide the design of ligands binding to different regions of the lipid bilayer.

Distinguishing features of ligand binding sites at the protein-bilayer interface

In order to understand how the features of ligand binding sites change within different solvent contexts, we examined the composition of amino acids present in ligand binding sites (Fig. 4, striped bars) and residues not involved in ligand binding (Fig. 4, solid bars) in the tail group region, head group region, and in soluble proteins (see the “Methods” subsection “Binding site analysis”). Residues were further classified as buried (Fig. 4, left), or solvent-exposed (Fig. 4, right).

Fig. 4. Comparison of amino acid composition of binding sites and other protein regions with respect to solvent.

Comparison of population residue types within binding sites (hatch pattern) and outside binding sites (solid fill) across different protein regions (Tail Group, Head Group, and Soluble Proteins). Residues are classified as either buried (solvent-exposed surface area (SASA) <15% in the absence of ligand, left) or solvent-exposed (SASA >15% in the absence of ligand, right). Error bars were generated using bootstrap sampling (2000 iterations) to calculate standard deviations of residue proportions.

Different protein regions show distinct amino acid compositions depending on their solvent environment, consistent with the hydrophobic nature of the lipid bilayer. Exposed residues in the lipid tail group region tend to be more hydrophobic than exposed residues in the lipid head group region, or in soluble proteins. On the other hand, buried residues within soluble proteins tend to be enriched in hydrophobic residues, reflecting the hydrophobic effect that drives protein folding60.

Ligand binding sites have different amino acid compositions than other protein regions. Regardless of solvent, both in buried and solvent-exposed areas, ligand binding sites are enriched in aromatic residues. Aromatic residues are able to form favorable pi-stacking interactions and van der Waals contacts with ligands. This trend has been recognized by other research groups examining the amino acid composition of ligand binding sites and has been suggested as a potential method for identifying druggable pockets61,62.

To bind to a protein, a ligand must effectively compete with solvent molecules occupying the binding site63. Stable interactions between protein and solvent make it less energetically favorable for a ligand to displace solvent molecules and bind to a protein. In water-solvated binding sites, polar residues interact favorably with water molecules. The amphipathic lipid bilayer favors exposure of hydrophilic residues at the lipid head regions and hydrophobic residues at the lipid tails. Consequently, exposing hydrophobic residues to the aqueous environment or lipid head groups, or polar residues to the lipid tails, destabilizes the protein’s interactions with the solvent. This instability reduces the energetic barrier for solvent displacement, facilitating ligand binding.

Our analysis supports this idea. In the lipid tail group region, ligand binding sites contain fewer hydrophobic residues than other protein regions not interacting with a ligand (Fig. 4, top). In fact, exposed residues in the lipid tail group region that makeup ligand binding sites are slightly enriched in polar and negatively charged residues, suggesting that ligands may leverage interactions with relatively rare exposed polar or charged residues to facilitate binding.

In the lipid head group region, this trend is inverted, and there are slightly more hydrophobic residues and fewer charged and polar residues in ligand binding sites (Fig. 4, center). Since lipid head groups interact favorably with charged and polar residues and unfavorably with hydrophobic residues, ligands can help stabilize their interaction with the protein by shielding hydrophobic residues from the polar/charged lipid head groups.

These distinct amino acid profiles observed in the tail group region, head group region, and in soluble proteins underline the importance of solvent context in shaping protein-ligand interactions and can aid in the identification of potential druggable pockets.

Case study 1: Ligand binding to the calcium-sensing receptor at the protein-bilayer interface

The calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), a homodimeric Class C GPCR, has been characterized as complex with a variety of ligands at the protein bilayer interface. CaSR is positively modulated by high levels of extracellular calcium, or by other ligands, and its activation initiates a signaling cascade that leads to increased intracellular calcium and the excretion of parathyroid hormone64,65. Positive allosteric modulators (cinacalcet, evocalcet, tecalcet) have been developed as CaSR targeting therapeutics to treat hyperparathyroidism, and negative allosteric modulators are in phase II clinical trials to treat autosomal dominant hypocalcemia type 165.

CaSR–ligand complexes have been determined for both calcimimetics and negative allosteric modulators including cinacalcet, evocalcet, tecalcet, and NPS-2143, all of which bind at the protein-lipid interface (Fig. 5)66–68. Cinacalcet and evocalcet adopt distinct conformations in each monomer66. In one, the ligands adopt a bent conformation (Fig. 5a) In the other, they adopt an extended conformation (Fig. 5b). NPS-2143 and tecalcet bind in bent conformations to both monomers (Fig. 5c, d).

Fig. 5. Poses of ligands bound to CaSR.

a Cinacalcet-bound (blue, PDB ID 7M3F, chain A) and evocalcet-bound (purple, PDB ID 7M3G, chain A) CaSR with ligands in the bent conformation. b Cinacalcet-bound (blue, PDB ID 7M3F, chain B) and evocalcet-bound (purple, PDB ID 7M3G, chain B) CaSR with ligands in the extended conformation. c Tecalcet-bound (green, PDB ID 7SIL, chain A) CaSR. d NPS-2143-bound (sand, PDB ID 7M3E) CaSR. e Chemical structures of the ligands cinacalcet, evocalcet, tecalcet, and NPS-2143.

The binding modes of the four ligands (Fig. 5) share some similarities. All four ligands possess a basic nitrogen atom which forms a salt bridge with Glu 837 and a hydrogen bond with Gln 681, although the distance/strength of this salt bridge depends on the conformation for cinacalcet and evocalcet. These are the only polar interactions common across these ligands (Fig. 5). The alcohol of NPS-2143 additionally forms a hydrogen bond with Tyr 825 (Fig. 5d). The ligands also interact extensively with hydrophobic residues in the pocket, especially Trp 818 and Phe 684 via pi-stacking. In NPS-2143, cinacalcet, and evocalcet these residues are engaged by a naphthalene, and this acts as the anchor which is constant between the bent and extended conformations for the latter two (Fig. 5 a, b,d). The methyl phenyl ether of tecalcet forms similar interactions with these residues (Fig. 5c).

NPS-2143, tecalcet, and cinacalcet all expose lipophilic groups (2-chlorobenzonitrile, chlorobenzene, and trifluorotoluene, respectively) to the bilayer. Evocalcet, however, presents a more polar benzylcarboxylic acid. In the extended conformation, this group is directed towards the extracellular lipid head groups, potentially engaging in polar or electrostatic interactions with them (Fig. 5b). In the bent conformation, the carboxylic acid is exposed to the bulk lipid tail environment (Fig. 5a). Although protonation and subsequent hydrogen bonding with the protein backbone (Trp 818) is possible55, the presence of a group with this low pKa in the nonpolar lipid environment is atypical (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Overall, ligands binding to CaSR agree with the trends discussed above: exposing uncharged/lipophilic groups to lipid tails and either burying polar/charged groups in the bilayer or exposing them to lipid head groups. However, the bent binding mode of evocalcet is an exception to the trend, exposing acidic oxygen to lipid tails. The existence of multiple binding modes also complicates any attempts to describe discrete strategies pursued for individual ligands.

Case study 2: Specific Interactions with lipid head groups contribute to drug binding to T-type calcium channel Cav3.3

In addition to being solvated by bulk lipids, some membrane proteins form complexes with individual stably-bound lipids. These “structural” lipids may in turn modulate the protein structure, function, and even ligand binding69–71. In our dataset, 13% of the structures had a resolved lipid within interaction distance (4 Å) of the ligand, forming a protein–lipid–ligand ternary complex. Specific interactions between the lipid and ligand, such as hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions, may significantly influence the free energy of ligand binding. Understanding these lipid-mediated interactions may significantly impact structure-based drug discovery at membrane-exposed sites.

An example of a membrane protein that forms a complex with a stably bound lipid is voltage-gated calcium channel 3.3 (Cav3.3), a T-type calcium channel72,73. A number of drugs inhibit Cav3.3 channels, including mibefradil (antihypertensive) otilonium bromide (used to treat spasmodic gut pain), and pimozide (antipsychotic). The activity of Cav3.3 is also modulated by interactions with lipid molecules74. He et al. published structures of Cav3.3 in the ligand-free, mibefradil-bound (Fig. 6a), otilonium bromide-bound (Fig. 6b) and pimozide-bound (Fig. 6c) forms73. In all of these structures, a phospholipid is observed in the central cavity of the channel near the center of the bilayer and participates in stabilizing drug binding. In the ligand-free and otilonium bromide-bound structures the lipid phosphate group is stabilized by a salt bridge with Lys 1379 while the lipid tail interacts with a protein cavity lined by hydrophobic residues. All three drugs interact substantially with the lipid and have a tertiary or quaternary ammonium capable of forming electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phosphate group.

Fig. 6. Drug and lipid binding to T-type calcium channel Cav3.3.

a Cav3.3 (white) and lipid (black) (PDB ID: 7WLI). b Mibefradil (orange) bound to Cav3.3 (white) and lipid (black) (PDB ID: 7WLJ). c Otilonium bromide (pink) bound to Cav3.3 (white) and lipid (black) (PDB ID: 7WLK). d Pimozide (green) bound to Cav3.3 (white) and lipid (black) (PDB ID: 7WLL).

CaseStudy 3: Ligands target the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome bcc complex at a quinol-binding site

The activity of membrane proteins can be natively modulated by specific interactions with cofactors embedded in the membrane, such as heme or quinone71,75. For some of these proteins, an effective drug design strategy may be to design molecules that alter interactions with those native cofactors.

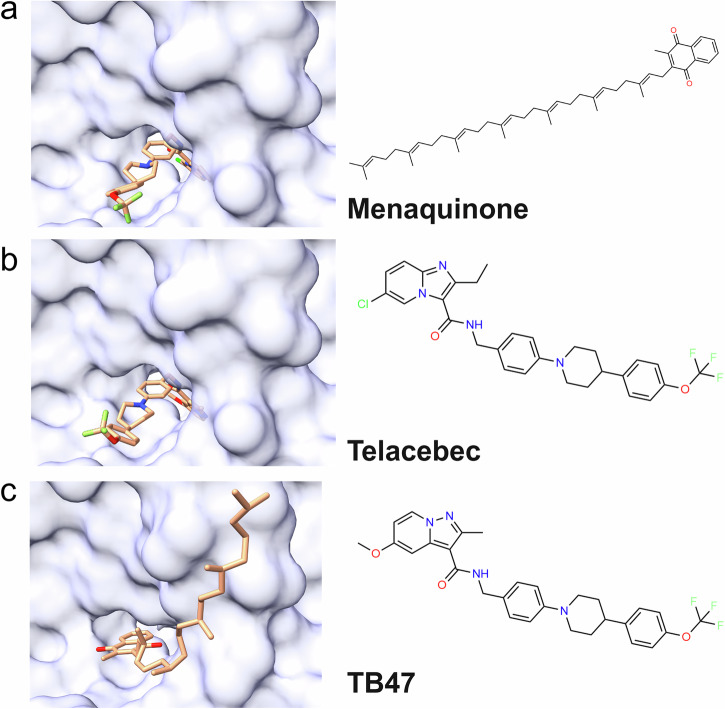

Cytochrome bcc complexes are an example of proteins that bind to a lipid-exposed cofactor. Cytochrome bcc complexes are important for mycobacterial survival as they establish a proton gradient essential for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis76. As such, they are attractive antibacterial drug targets77. M. tuberculosis cytochrome bcc is targeted by the phase 2 drug Telacebec and preclinical molecule TB47. Both ligands bind to the quinol oxidation site (QP site), competitively inhibiting the binding and oxidation of quinol.

Zhou et al. published structures of the mycobacterial cytochrome bcc complex with menaquinone, Telacebec, or TB47 occupying the QP site (Fig. 7)78. The menaquinone molecule in the QP site makes hydrophobic contacts with the protein with the isoprenoid tail exposed to bulk lipid (Fig. 7a). Both Telacebec and TB47 overlap with the menaquinone binding site, primarily exposing lipophilic trifluoromethyl groups to the bilayer (Fig. 7b, c). Telacebec and TB47 additionally form hydrogen bonds with Thr 313, Glu 314, and His 375 (not shown).

Fig. 7. Ligands bound to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome bcc complex.

a Menaquinone (teal) bound to M. tuberculosis cytochrome bcc (white) (PDB ID: 7E1V). b Telacebec (orange) bound to M. tuberculosis cytochrome bcc (white) (PDB ID: 7E1W). c TB47 (pink) bound to M. tuberculosis cytochrome bcc (white) (PDB ID: 7E1X).

Other groups have used structure-based-drug design strategies to identify modulators that target the cytochrome bcc cofactor binding sites79,80. Notably, Hao et al. used a pharmacophore-linked fragment virtual screening to identify a picomolar inhibitor of the cytochrome bc1 complex which competes for a ubiquinol binding site81. These examples demonstrate that targeting membrane-bound cofactor binding sites is an effective strategy for drug discovery.

Conclusions

Lipid-exposed ligand binding sites are important for a large number of therapeutically relevant protein targets, but the study of these sites has been hindered by a low volume of structural data and a lack of systematic review. Here, we curated LILAC-DB, a dataset of 413 structures of druglike molecules bound at the protein-lipid interface, including 25 FDA-approved drugs and 21 molecules currently in clinical trials. While the size of the data set is relatively small, it thoroughly covers the chemical space that has been structurally characterized and bound to these sites to date. Our analysis identified trends in both lipid-interfacing binding sites on proteins and in the molecules engaging them. LILAC-DB is available for download, providing a valuable resource for further investigation of these interactions.

Molecules that bind to lipid-exposed sites tend to be larger, more lipophilic, and contain more halogen atoms than other drug-like molecules. Atomic properties of these ligands vary significantly with respect to lipid exposure and depth in the lipid bilayer. These findings suggest that there are trends that can be exploited to optimize molecular properties for lipid-exposed binding sites, specifically the large importance of matching the lipophilicity/partial charge of exposed atoms to their solvent environment. Our data indicates that a more important consideration for adapting structure-based drug design techniques to lipid-exposed sites is optimizing the properties of exposed ligand atoms to their solvent environment, rather than buried ones. These trends may inform the construction of specialized chemical libraries, ideally even to the level of tuning a molecule to bind at specific regions in the bilayer, and improved models of the solvation/desolvation process.

We also showed that amino acid compositions of binding sites exposed to the lipid bilayer are distinct from soluble binding sites or buried residues, which may be useful for the identification of druggable sites in the bilayer. Incorporating insights into ligand positioning, orientation, and conformation within the lipid bilayer can enhance structure-based drug discovery efforts targeting membrane-associated proteins, especially by improving binding site and ligand conformation prediction. However, several challenges remain open.

The heterogeneous nature of lipid bilayers, with varying compositions across different cell types and subcellular compartments, poses a challenge in the rational design of these ligands. The proteins analyzed here span a diverse range of subcellular membranes and source organisms. While these proteins likely interact with membranes of varying lipid composition, our analysis did not reveal significant correlations between specific lipid environments and ligand properties or ligand-protein interactions (data available upon request). Furthermore, the dataset analyzed here is limited by the availability of high-quality models of certain protein classes. Notably, there are no β-barrel membrane proteins in the dataset. Many membrane proteins—especially less-studied classes—currently lack high-resolution structural data. Additionally, there may be a bias in the chemical space for which structures have been determined, as the difficulty in obtaining structures of these complexes means only more promising molecules are characterized. Nevertheless, the trends observed in ligand properties and binding site characteristics are likely applicable to a broader range of membrane proteins, due to the consistent physicochemical constraints imposed by the bilayer.

These outstanding challenges provide opportunities to accelerate structure-based drug design targeting the protein–lipid interface. Compared to traditional drug design targeting soluble proteins, there are few validated methodologies for structure-based drug design at lipid-exposed sites. Methods have been developed to incorporate molecular cLogP into docking scores82, to more accurately screen for compounds that bind to lipid-exposed sites. However, this method was trained and validated on a small dataset mostly composed of lipid molecules and cofactors. Datasets such as the one presented here will be helpful to benchmark the performance of new scoring functions in predicting the binding poses and energies of druglike molecules at the protein-bilayer interface. Furthermore, being able to anticipate the preferred depth and orientation of a molecule in the lipid bilayer would help guide the drug discovery effort. To date, high throughput, validated models for predicting these properties remain limited. From a theoretical perspective, the heterogeneous nature of the lipid bilayer necessitates the design of new frameworks capable of capturing the varying dielectric and electrostatic features in and near the membrane. We hope that LILAC-DB and the analysis presented here can inform and motivate further work on structure-based drug design against membrane-exposed binding sites.

Methods

Dataset curation

To construct a high-quality dataset of ligands bound at the protein-bilayer interface, we systematically curated ligand–protein-membrane complexes from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)83. Initially, we retrieved all PDB structures containing at least one ligand and annotated them as membrane proteins. To focus on druglike molecules, ligands classified as cofactors or matching SMARTS patterns for polyethylene glycol, a nucleobase, porphyrin ring, or lipid were excluded.

To accurately position the protein within the membrane environment, we obtained membrane-oriented structures from the orientations of proteins in membranes (OPM)84 database. For structures lacking OPM entries, the positioning of proteins in membranes (PPM)84 source code was used to generate membrane orientations. PPM is a well-validated method of determining the orientation of a membrane protein in the lipid bilayer by minimizing its predicted free energy of transfer into a hydrophobic slab, and OPM is a database of membrane protein structures that have been pre-oriented with PPM. Subsequently, we determined ligand proximity to the bilayer by assessing if any ligand atom was within the Z-bounds defined by OPM or PPM for the membrane.

For ligands positioned within the membrane Z-bounds, we used MSMS85, an efficient program for protein surface calculation to generate a 3D triangular mesh surface encompassing the protein excluding all ligands. A probe radius of 2.7 Å was chosen based on tests with a small dataset of structures containing ligands at the protein–lipid interface, as it provided the most accurate results.

A ligand atom was considered exposed to the bilayer if its X/Y coordinates fell outside the polygon created by intersecting the protein surface with the X/Y plane at the ligand atom’s Z-coordinate (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To ensure data quality, all identified ligand–protein-membrane complexes underwent extensive manual inspection. Ligands classified as cofactors, false positives from the computational filtering, or those exhibiting poor electron density were excluded. This curation process yielded a high-quality dataset of druglike molecules bound at the protein-bilayer interface, suitable for subsequent analysis.

To avoid analyzing redundant systems, the dataset was further filtered to create LILAC-DB (Non-Redundant), a version containing only one copy of each ligand in a given pose bound to a protein. In cases where there were multiple structures of the same protein–ligand pair, the highest resolution structure was kept. If a structure had multiple copies of the same ligand bound, the ligand poses were clustered with a 2 Å cutoff, and only the first ligand in each cluster was retained. This step ensured that distinct binding poses were preserved, while only one copy of redundant poses (e.g., multimeric proteins with ligands bound in the same pose to each monomer) was analyzed. All analyses presented in this paper were conducted using LILAC-DB (Non-Redundant). Both LILAC-DB (Refined), which includes all curated entries, and LILAC-DB (Non-Redundant) are available for download.

Analysis of ligand atoms

To analyze the atomic properties of ligands exposed to different regions of the lipid bilayer, all ligands were protonated at pH 7.4 using molscrub86, a rules-based method for assigning protonation states. The percent distance from the hydrocarbon core was calculated for ligand atoms located within the tail group region, as defined by OPM’s hydrocarbon thickness. This calculation was performed by dividing the ligand’s Z-coordinate in the OPM-aligned structure by half the hydrophobic thickness defined by OPM and multiplying by 100. This approach accounts for variations in hydrophobic thickness among different proteins. The head group regions were defined as a 6 Å-wide region extending outward from the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayer, as determined by OPM, in both the positive and negative Z-directions. While the head group region may extend beyond 6 Å, we truncated our analysis at this cutoff because very few atoms in the dataset were located beyond this distance, ensuring statistically significant analysis. To analyze the atomic properties of ligands within these different regions, we divided the lipid tail region into 10 bins and the inner and outer head group regions into five bins each. We then averaged the atomic properties within each bin to plot how atomic properties change with respect to position in the bilayer (Supplementary Data 2).

Binding site analysis

We analyzed amino acid compositions within ligand binding sites at the protein-lipid bilayer interface and of soluble binding sites (Supplementary Data 3, 4). Residues were defined as part of a binding site if any of their atoms were within 4 Å of any ligand atom. Given that amino acid composition varies with solvent exposure, residues were categorized as buried (percent exposed surface area <15%) or solvent-exposed (percent exposed surface area >15%). Additionally, residues were classified based on their location within the lipid bilayer head or tail groups; residues within the hydrophobic thickness defined by OPM were classified as in the lipid tail group region, and residues within 6 Å in the Z direction of the tail groups were classified as in the lipid head group region. To avoid the overrepresentation of proteins with multiple structures, residues outside the binding site were considered only once for each unique UniProt ID in the dataset. To analyze soluble binding sites, 294 structures were randomly selected from the 2020 PDBbind48 refined set. The amino acid categories were defined as follows: hydrophobic (alanine, valine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine), aromatic (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan), polar (serine, threonine, asparagine, glutamine, cysteine), positively charged (lysine, arginine, histidine), negatively charged (aspartic acid, glutamic acid), and other (proline, glycine).

Case studies

All interactions between the protein and ligands were analyzed through visual inspection in ChimeraX87.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM069832 (S.F.), and NSF Graduate Research Fellowship to A.P.B.

Author contributions

A.P.B., M.H., and S.F. conceptualized the study. A.P.B. collected, curated and annotated the data, performing the analysis, with contributions from M.H. and S.F. A.P.B. wrote the original draft, M.H. and S.F. contributed writing the manuscript. S.F. supervised the research and acquired funding for the study.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The summary of system properties in the database is available as Supplementary Data File 1. The data used to generate Fig. 3 is in Supplementary Data Files 2 and 3 and the data used to generate Fig. 4 is available in Supplementary Data File 4. The full LILAC-DB dataset, including all structures, is available on the Zenodo open-access repository at https://zenodo.org/records/14835079.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-025-01472-8.

References

- 1.Yin, H. & Flynn, A. D. Drugging membrane protein interactions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng.18, 51–76 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos, R. et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.16, 19–34 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payandeh, J. & Volgraf, M. Ligand binding at the protein–lipid interface: strategic considerations for drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.20, 710–722 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, Y., Yu, Z., Xiao, W., Lu, S. & Zhang, J. Allosteric binding sites at the receptor–lipid bilayer interface: novel targets for GPCR drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today26, 690–703 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szlenk, C. T., Gc, J. B. & Natesan, S. Does the lipid bilayer orchestrate access and binding of ligands to transmembrane orthosteric/allosteric sites of G protein-coupled receptors? Mol. Pharmacol.96, 527–541 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopoulos, A. Allosteric binding sites on cell-surface receptors: novel targets for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.1, 198–210 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felder, C. C. GPCR drug discovery-moving beyond the orthosteric to the allosteric domain. In Advances in Pharmacology Vol. 86 (ed. Witkin, J. M.) Ch. 1, 1–20 (Academic Press, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Owen, R. M. et al. Design and identification of a novel, functionally subtype selective GABAA positive allosteric modulator (PF-06372865). J. Med. Chem.62, 5773–5796 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobin, A. B. A golden age of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor modulation in neurological diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.23, 743–758 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burst, C. A., Swanson, M. A. & Bohn, L. M. Structural and functional insights into the G protein-coupled receptors: CB1 and CB2. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 51, 1533–1543 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Price, M. R. et al. Allosteric modulation of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol.68, 1484–1495 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao, Z. et al. Structure of an allosteric modulator bound to the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol.15, 1199–1205 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comparative molecular dynamics simulation studies of realistic eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and archaeal membranes. J. Chem. Inf. Model.10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01514. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kučerka, N. et al. Lipid bilayer structure determined by the simultaneous analysis of neutron and X-ray scattering data. Biophys. J.95, 2356–2367 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anisotropic solvent model of the lipid bilayer. 2. Energetics of insertion of small molecules, peptides, and proteins in membranes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 10.1021/ci200020k (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Castanho, M. A. R. B. & Fernandes, M. X. Lipid membrane-induced optimization for ligand–receptor docking: recent tools and insights for the “membrane catalysis” model. Eur. Biophys. J.35, 92–103 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harada, R., Morita, R. & Shigeta, Y. Free-energy profiles for membrane permeation of compounds calculated using rare-event sampling methods. J. Chem. Inf. Model.63, 259–269 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan, X., Raniolo, S., Limongelli, V. & Xu, Y. The molecular mechanism underlying ligand binding to the membrane-embedded site of a G-protein-coupled receptor. J. Chem. Theory Comput.14, 2761–2770 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacCallum, J. L. & Tieleman, D. P. Interactions between small molecules and lipid bilayers. In Current Topics in Membranes Vol. 60 (ed. Feller, S. E.) Ch. 8, 227–256 (Academic Press, 2008).

- 20.Alberts, B. et al. Membrane proteins. In Molecular Biology of the Cell 4th edn (ed. Gibbs, S.) (Garland Science, 2002).

- 21.Mbaye, M. N. et al. A comprehensive computational study of amino acid interactions in membrane proteins. Sci. Rep.9, 12043 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baláž, Š. Lipophilicity in trans-bilayer transport and subcellular pharmacokinetics. Perspect. Drug Discov. Des.19, 157–177 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vauquelin, G. On the ‘micro’-pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms that contribute to long-lasting drug action. Expert Opin. Drug Discov.10, 1085–1098 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sykes, D. A. et al. Observed drug-receptor association rates are governed by membrane affinity: the importance of establishing “micro-pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships” at the β2-adrenoceptor. Mol. Pharmacol.85, 608–617 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes, D. G., Sarmiento, J. G. & Herbette, L. G. Kinetics of binding of membrane-active drugs to receptor sites. Diffusion-limited rates for a membrane bilayer approach of 1,4-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists to their active site. Mol. Pharm.27, 612–623 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Structure-based prediction of drug distribution across the headgroup and core strata of a phospholipid bilayer using surrogate phases. Mol Pharm.10.1021/mp5003366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bemporad, D., Luttmann, C. & Essex, J. W. Computer simulation of small molecule permeation across a lipid bilayer: dependence on bilayer properties and solute volume, size, and cross-sectional area. Biophys. J.87, 1–13 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arcario, M. J., Mayne, C. G. & Tajkhorshid, E. A membrane-embedded pathway delivers general anesthetics to two interacting binding sites in the Gloeobacter violaceus ion channel. J. Biol. Chem.292, 9480–9492 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sargent, D. F., Bean, J. W. & Schwyzer, R. Conformation and orientation of regulatory peptides on lipid membranes: key to the molecular mechanism of receptor selection. Biophys. Chem.31, 183–193 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poongavanam, V., Wieske, L. H. E., Peintner, S., Erdélyi, M. & Kihlberg, J. Molecular chameleons in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem.8, 45–60 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadourakis, M. et al. Alchemical free energy calculations on membrane-associated proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput.19, 7437–7458 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Axelrod, D. & Wang, M. D. Reduction-of-dimensionality kinetics at reaction-limited cell surface receptors. Biophys. J.66, 588–600 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo, J. et al. Magnetically aligned bicelles to study the orientation of lipophilic ligands in membrane bilayers. J. Med. Chem.51, 6793–6799 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, F. et al. Dynamic NMR study and theoretical calculations on the conformational exchange of valsartan and related compounds. Magn. Reson. Chem.45, 929–936 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antihypertensive drug valsartan in solution and at the AT1 receptor: conformational analysis, dynamic NMR spectroscopy, in silico docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model.10.1021/ci800427s (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Liu, F. et al. Structural identification of a hotspot on CFTR for potentiation. Science364, 1184–1188 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hargrove, T. Y. et al. Structural analyses of Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase complexed with azole drugs address the molecular basis of azole-mediated inhibition of fungal sterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem.292, 6728–6743 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook, C. et al. Challenges of absolute binding free energies for membrane exposed binding pockets. Preprint at 10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-9hwjs (2024).

- 39.Ladokhin, A. S. Distribution analysis of depth-dependent fluorescence quenching in membranes: a practical guide. In Methods in Enzymology. (ed. Brand, L., Johnson, M. L.) Vol. 278, 462–473 (Academic Press, 1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Balaz, S. Modeling kinetics of subcellular disposition of chemicals. Chem. Rev. 10.1021/cr030440j (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Róg, T., Girych, M. & Bunker, A. Mechanistic understanding from molecular dynamics in pharmaceutical research 2: Lipid membrane in drug design. Pharmaceuticals14, 1062 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun R, Dama JF, Tan JS, Rose JP, & Voth GA. Transition-tempered metadynamics is a promising tool for studying the permeation of drug-like molecules through membranes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00206 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Klamt, A., Huniar, U., Spycher, S. & Keldenich, J. COSMOmic: a mechanistic approach to the calculation of membrane−water partition coefficients and internal distributions within membranes and micelles. J. Phys. Chem. B10.1021/jp801736k (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Juračka, J., Šrejber, M., Melíková, M., Bazgier, V. & Berka, K. MolMeDB: molecules on membranes Database Database2019, baz078 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danelius, E. et al. Solution conformations explain the chameleonic behaviour of macrocyclic drugs. Chem.—Eur. J.26, 5231–5244 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopes, S. C. D. N. & Castanho, M. A. R. B. Overview of common spectroscopic methods to determine the orientation/alignment of membrane probes and drugs in lipidic bilayers. Curr. Org. Chem. 9, 889–898 (2005).

- 47.Knox, C. et al. DrugBank 6.0: the DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res.52, D1265–D1275 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, R. X., Fang, X.L., Yipin Lu, Y., Yang, C.-Y. & Wang, S. M. The PDBbind database: methodologies and updates. J. Med. Chem.10.1021/jm048957q (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Durairaj, J. et al. PLINDER: the protein–ligand interactions dataset and evaluation resource. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2024.07.17.603955v1.

- 50.Zdrazil, B. et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res.52, D1180–D1192 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dickson, C. J., Hornak, V., Bednarczyk, D. & Duca, J. S. Using membrane partitioning simulations to predict permeability of forty-nine drug-like molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model.59, 236–244 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coimbra, S. et al. The importance of intramolecular hydrogen bonds on the translocation of the small drug piracetam through a lipid bilayer. RSC Adv.11, 899–908 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerebtzoff, G., Li-Blatter, X., Fischer, H., Frentzel, A. & Seelig, A. Halogenation of drugs enhances membrane binding and permeation. ChemBioChem5, 676–684 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nunes, R. S., Vila-Viçosa, D. & Costa, P. J. Halogen bonding: an underestimated player in membrane–ligand interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.143, 4253–4267 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacCallum, J. L., Bennett, W. F. D. & Tieleman, D. P. Distribution of amino acids in a lipid bilayer from computer simulations. Biophys. J.94, 3393–3404 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wildman, S. A. & Crippen, G. M. Prediction of physicochemical parameters by atomic contributions. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.39, 868–873 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heiden, W., Moeckel, G. & Brickmann, J. A new approach to analysis and display of local lipophilicity/hydrophilicity mapped on molecular surfaces. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des.7, 503–514 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rasmussen, M. H., Christensen, D. S. & Jensen, J. H. Do machines dream of atoms? Crippen’s logP as a quantitative molecular benchmark for explainable AI heatmaps. SciPost Chem.2, 002 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y. Q. et al. End-to-end differentiable construction of molecular mechanics force fields. Chem. Sci.10.1039/D2SC02739A (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Lins, L. & Brasseur, R. The hydrophobic effect in protein folding. FASEB J.9, 535–540 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soga, S., Shirai, H., Kobori, M. & Hirayama, N. Use of amino acid composition to predict ligand binding sites. J. Chem. Inf. Model.47, 400–406 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khazanov, N. A. & Carlson, H. A. Exploring the composition of protein-ligand binding sites on a large scale. PLoS Comput. Biol.9, e1003321 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mondal, J., Friesner, R. A. & Berne, B. J. Role of desolvation in thermodynamics and kinetics of ligand binding to a kinase. J. Chem. Theory Comput.10, 5696–5705 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown, E. M. et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature366, 575–580 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hannan, F. M., Kallay, E., Chang, W. H., Brandi, M. L. & Thakker, R. V. The calcium-sensing receptor in physiology and in calcitropic and noncalcitropic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-018-0115-0#Sec20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Gao, Y. et al. Asymmetric activation of the calcium-sensing receptor homodimer. Nature595, 455–459 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wen, T. et al. Structural basis for activation and allosteric modulation of full-length calcium-sensing receptor. Sci. Adv.7, eabg1483 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zuo, H. et al. Promiscuous G-protein activation by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature629, 481–488 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laganowsky, A. et al. Membrane proteins bind lipids selectively to modulate their structure and function. Nature510, 172–175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levental, I. & Lyman, E. Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.24, 107–122 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Westerlund, A. N., Fleetwood, O., Pérez-Conesa, S. & Lucie Delemotte, L. Network analysis reveals how lipids and other cofactors influence membrane protein allostery. J. Chem. Phys.https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/153/14/141103/316588 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Bean, B. P. Classes of calcium channels in Vertebrate cells. Annu. Rev. Physiol.51, 367–384 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.He, L. et al. Structure, gating, and pharmacology of human CaV3.3 channel. Nat. Commun.13, 2084 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chemin, J., Cazade, M. & Lory, P. Modulation of T-type calcium channels by bioactive lipids. Pflüg. Arch.—Eur. J. Physiol.466, 689–700 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loll, B., Kern, J., Saenger, W., Zouni, A. & Biesiadka, J. Lipids in photosystem II: interactions with protein and cofactors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Bioenerg.1767, 509–519 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koul, A. et al. Diarylquinolines are bactericidal for dormant mycobacteria as a result of disturbed ATP homeostasis*. J. Biol. Chem.283, 25273–25280 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cook, G. M. et al. Oxidative phosphorylation as a target space for tuberculosis: success, caution, and future directions. Microbiol. Spectr. 5, 10.1128/microbiolspec.tbtb2-0014-2016 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Zhou, S. et al. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome bcc in complex with Q203 and TB47, two anti-TB drug candidates. eLife10, e69418 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harikishore, A., Chong, S. S. M., Ragunathan, P., Bates, R. W. & Grüber, G. Targeting the menaquinol binding loop of mycobacterial cytochrome bd oxidase. Mol. Divers.25, 517–524 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seitz, C. et al. Targeting tuberculosis: novel scaffolds for inhibiting cytochrome bd oxidase. J. Chem. Inf. Model.64, 5232–5241 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hao, G.-F. et al. Computational discovery of picomolar Qo site inhibitors of cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 11168–11176 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morita, R., Shigeta, Y. & Harada, R. Efficient screening of protein-ligand complexes in lipid bilayers using LoCoMock score. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des.37, 217–225 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berman, H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 235–242 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lomize, M. A., Pogozheva, I. D., Joo, H., Mosberg, H. I. & Lomize, A. L. OPM database and PPM web server: resources for positioning of proteins in membranes. Nucleic Acids Res.40, D370–D376 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanner, M.F., Olson, A.J. & Spehner, J.C. Fast and robust computation of molecular surfaces. Proc. 11th ACM Symp. comp. Geom. C6–C7 (1995).

- 86.Diogo, S. -M., Manuel, L., Joani, M., Amy, H., Althea, H. -H. & Stefano, F. https://github.com/forlilab/molscrub. (Accessed 01/09/2024)

- 87.Meng, E. C. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci.32, e4792 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Srivastava, A. et al. High-resolution structure of the human GPR40 receptor bound to allosteric agonist TAK-875. Naturehttps://www.nature.com/articles/nature13494 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.McPhillie, M. J. et al. Potent tetrahydroquinolone eliminates apicomplexan parasites. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00203 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Gao, Y., Cao, E., Julius, D. & Cheng, Y. TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature534, 347–351 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The summary of system properties in the database is available as Supplementary Data File 1. The data used to generate Fig. 3 is in Supplementary Data Files 2 and 3 and the data used to generate Fig. 4 is available in Supplementary Data File 4. The full LILAC-DB dataset, including all structures, is available on the Zenodo open-access repository at https://zenodo.org/records/14835079.