Summary

Optimizing molecular structures in oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is crucial for enhancing catalytic efficiency and stability, particularly with respect to the effective adsorption and conversion of reaction intermediates. Sulfur-containing heterocyclic compound thiophene can precisely modulate the electronic states and local charge densities, thereby fine-tuning the adsorption and reactivity of microporous polymers, yet, it remains a largely unexplored area. Herein, thiophene-based building blocks featuring diversified linkers into a phenyl-containing model Ph-CMP are developed, affording the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP and the thiophene-linked BCT-CMP. The electron density and adsorption capacity of the frameworks are well regulated through condensation and connecting modification, showing excellent half-wave potentials compared to the reversible hydrogen electrode, surpassing even most metal-free polymer electrocatalysts. Through theoretical calculations and experimental results, we have validated that the thiophene-fused skeleton (BPT-CMP) triggers the activation of thiophene units, with the exposed pentatomic heterocyclic carbon atom (site-3) serving as the catalytic active site.

Subject areas: Catalysis, Electrochemistry, Materials science

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Thiophene-based moieties modulated conjugated polymers show excellent ORR performance

-

•

The boron β-diketone units endow the polymer with excellent electron-accepting ability

-

•

The thiophene-fused BPT-CMP promotes charge transfer and increases oxygen adsorption sites

Catalysis; Electrochemistry; Materials science

Introduction

The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is crucial for electrochemical energy conversion, playing a pivotal role in energy conservation, emission reduction, and environmental pollution mitigation.1,2,3 Due to the high energy barrier inherent in the reaction process, efficient electrocatalysts are urgently needed to minimize their overpotential, resulting in increased energy efficiency, accelerated reaction kinetics, and reduced energy consumption in electrochemical energy conversion systems.4,5,6 Currently, platinum-based electrocatalysts are widely employed for ORR due to their exceptional catalytic activity and stability. However, their high cost, low crustal abundance, and limited methanol tolerance hinder further commercialization.7,8,9 To address these issues, the metal-free carbon-based electrocatalysts have been extensively explored as a promising alternative, focusing on charge redistribution as active centers to enhance fuel cell performance.10,11,12 While modulation engineering such as introducing structural defects and heteroatom doping through high-temperature pyrolysis, has proven effective,13,14,15 precisely designing metal-free carbon-based electrocatalysts with well-defined molecular structures and abundant active sites remains a significant challenge.

Conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs) represent a unique class of multifunctional porous materials featuring extended π-conjugated structures, permanent nanopores, high surface area, and diverse functional building blocks,16,17 making CMPs a cost-effective and ideal choice for applications optoelectronic materials,18,19 gas separation,20,21 catalysis,22,23 and drug delivery.24,25 Furthermore, CMPs possess abundant pore channels, controlled electronic environments, tailored site distribution, and remarkable thermal and chemical stability, rendering them highly promising for efficient and sustainable ORR catalysis.26,27,28 Compared to conventional building blocks in CMP frameworks, thiophene, a class of heterocyclic units, offers advantages such as distinctive electronic structures and excellent chemical stability.29,30,31 The rigid aromatic thiophene units, characterized by their peripheral π-electron topologies, enable exceptional intramolecular charge delocalization within the conjugated frameworks. Additionally, sulfur (S) atoms within the thiophene unit can induce charge redistribution and modify the electronic properties of adjacent carbon atoms. Consequently, CMPs containing thiophene exhibit numerous active sites and effective oxygen intermediate adsorption, enhancing the catalytic activity.32,33 Thus, incorporating thiophene units into precisely defined conjugated polymer frameworks is highly advantageous.

Biopolymers are crucial in synthesizing carbon materials due to their renewable and non-toxic properties. Given that the ocean covers three-quarters of the Earth’s surface, abundant sea resources represent a significant source of these materials.34,35 Alginate, an anionic and non-toxic polysaccharide naturally occurring in brown algae and certain bacteria, consists of α-L-guluronate (G) and β-D-mannuronate (M) residues linked by 1,4-glycosidic bonds. Additionally, alginate macromolecules are abundant in carboxyl and hydroxyl groups.36,37 During carbonization, these functional groups are released as carbon oxides and water, enabling the polymeric carbon structure to transform into carbon materials, which makes alginate an ideal precursor for producing porous carbon materials. Notably, by chelate divalent and trivalent metal ions, such as Ca2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, and Fe3+, alginate can form an “egg-box” structure, which is advantageous for synthesizing metal-doped or metal-free three-dimensional carbon nanomaterials with multimodal pores. Compared to reduced graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes, this carbon-based material derived from marine biomass maintains high conductivity and supports the sustainable utilization of marine resources.

Herein, two thiophene-containing CMPs based on electron-deficient boron β-diketone units were designed and synthesized as ORR electrocatalysts (Scheme 1) by replacing the original phenyl units (Ph-CMP) with benzothiophene (BPT-CMP) and phenylthiophene units (BCT-CMP). The introduction of thiophene heterocycles breaks the uniform electron distribution of the molecular skeleton and achieves typical donor (D)-acceptor (A) properties. The thiophene linker regulating strategy further adjusts the electronic environment and enhances the interfacial active centers. The thiophene-fused BPT-CMP with biochar CCA as a support skeleton exhibits superior ORR activity (half-wave potential of 0.75 V), surpassing most reported carbon-based electrocatalysts. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that the active adsorption sites of thiophene-based CMPs originate from the carbon atom (site-3) on the thiophene unit. Importantly, the thiophene linker strategy can modulate local charge redistribution, increase dipole moment, and enhance catalytic reaction kinetics.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of the CMPs based on electron-deficient boron β-diketone units for Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

To implement the thiophene linker strategy, we intentionally used boron β-diketone monomers to construct a series of CMP catalysts (Figure S4C). The boron β-diketone based on boron-oxygen coordination bond (B←O) as a Lewis acid has excellent electron-accepting ability. In addition, the formation of stable six-membered boron-chelating rings in boron β-diketone units can suppress nonradiative energy dissipation through interconversion of O–H stretching mode between ketone and enol forms and further prolong π-conjugation of the skeleton to enhance electron-transporting ability.38 Meanwhile, the selected thiophene units with a delocalized π-electron system provide a rigid and planar structure, large surface area, and high-density activity, promoting intramolecular charge transfer and increasing oxygen adsorption sites in the polymer skeleton.39,40 Considering these factors, two CMPs were synthesized by reacting 1,3,5-triphenylamine with organic linkers 1,3,5-tri(benzothiophene)benzene (BPT) or 1,3,5-tri(2-thienyl)benzene (BCT) under solvothermal conditions via a Knoevenagel condensation reaction, denoted as BPT-CMP and BCT-CMP, respectively. The resulting CMPs demonstrate exceptional thermal stability, with decomposition temperatures (Td, 10% weight loss) exceeding 200°C (Figure S1A). Additionally, carbonized marine polysaccharide (CCA) is used as a support structure to improve the dispersion of the synthesized CMPs, offering the advantage of preserving high conductivity while promoting the sustainable use of marine resources.41

The influence of thiophene units on the electronic properties of metal-free organic molecules was investigated using DFT calculations. In metal-free carbon material systems, the inherently uniform charge distribution poses a challenge to achieving high catalytic efficiency. In Ph-CMP, negative charges are dispersed throughout the entire molecular skeleton (Figure 1),42 indicating effective electron delocalization. In contrast, the majority of charges in BPT-CMP and BCT-CMP are localized primarily around the thiophene units, disrupting the uniform charge distribution within the conjugated skeleton, and thereby regulating the electron density and adsorption capacity at specific active sites. Dipole moments, which serve as indicators of charge distribution and structural symmetry, are crucial for affecting molecular adsorption and reaction.43 DFT calculations indicate that thiophene-containing CMPs, BPT-CMP and BCT-CMP, exhibit dipole moments of 12.89 and 12.83 Debye, respectively, which are significantly higher than that of Ph-CMP (11.54 Debye). This observation suggests that the incorporation of thiophene units as building blocks enhances the molecular polarity of the CMPs, potentially facilitating intramolecular charge transfer processes.

Figure 1.

The calculated Kohn-Sham LUMOs, HOMOs, and electrostatic potential surface maps of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and solid-state 13C NMR spectrum were employed to characterize the chemical structures of the CMP frameworks. As depicted in Figure 2A, the FTIR spectra of these CMPs show a characteristic C=C stretching vibration mode at 1,588 cm−1 and the disappearance of the C=O stretching bands at 1,686 cm−1 from the thiophene comonomer. In addition, the absorption peak around 1,498 cm−1 corresponds to the deformation vibration of the C−S−C bond, indicating that the five-membered heterocyclic structure containing sulfur atoms has been successfully introduced into both BCT-CMP and BPT-CMP.44 The solid-state 13C NMR spectra of CMPs exhibit a prominent peak at 143 ppm (Figure 2B), corresponding to the thiophene heterocycle. Additionally, the vibration peak at 137 ppm is indicative of carbon atoms in the unsaturated C=C. These results confirm the successful Knoevenagel condensation reaction.45,46 To further assess the stability of these CMPs, they were exposed to solutions of 0.1 M KOH and 6.0 M KOH. FTIR spectroscopy analysis demonstrated that the CMP systems maintained their original molecular skeletons (Figures S1B–S1D), which is crucial for the ORR. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that these CMPs exhibit aggregated regular spherical and stick morphologies with micrometer-scale dimensions (Figures 2C and S2). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirmed the uniform distribution of O, S, and B atoms across the surface of CMPs, thereby excluding the influence of any residual reaction catalyst on the CMPs’ performance. Furthermore, the specific surface area and permanent porosity were determined using nitrogen (N2) adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K (Figures S3). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP is 8.02 m2 g−1 and the thiophene-linked BCT-CMP is 7.01 m2 g−1. The corresponding pore size adsorption curves indicate that the change of thiophene linkers did not significantly alter the microscopic porosity and surface area of the conjugated microporous polymers.

Figure 2.

Structural and morphological characterization of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP

(A) The FT-IR spectra of the three CMPs and the corresponding comonomers.

(B) The solid-state 13C NMR spectrum of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP.

(C) SEM image and corresponding EDS mappings of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

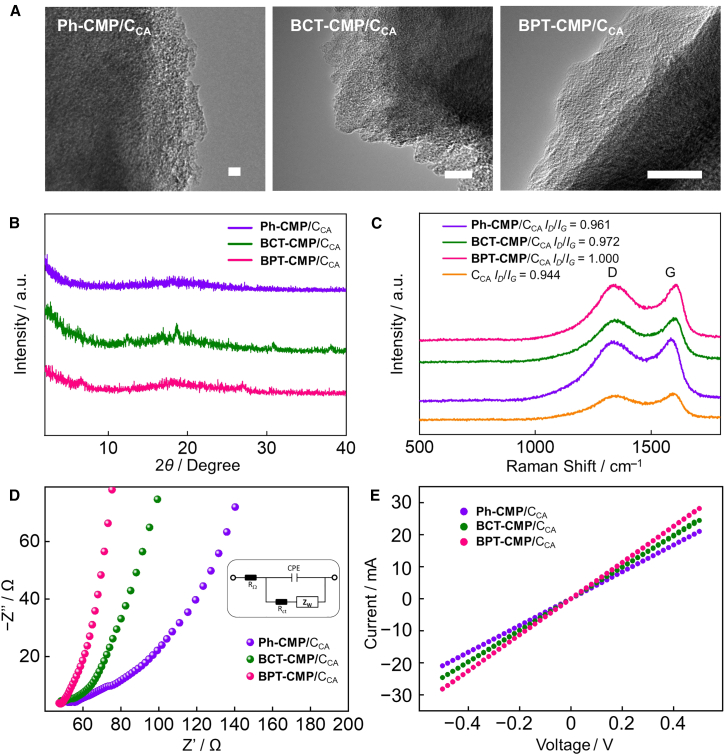

To gain a deeper understanding of the blending morphology of CMP heterostructures, TEM was utilized to observe the blended sample morphology (Figure 3A). The TEM images of the CMP/CCA revealed a closely integrated state between the two components. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis certified the tight packing of the CMP/CCA blends and verified the amorphous morphology of the CMPs (Figures 3B and S4A). Following the combination of CCA with disordered CMPs, strong D-band and G-band intensities were observed in the Raman spectra of all CMP blends (Figure 3C). The intensity ratios of the D-band to G-band (ID/IG) for Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA were 0.961, 0.972, and 1.000, respectively, exceeding the 0.944 ratio of CCA, indicating that the incorporation of CMP increases the disorder within the blend. Furthermore, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) results for Ph-CMP/CCA showed the highest arc radius and charge transfer resistance (Rct), suggesting that the inclusion of the thiophene unit aids in reducing charge transfer resistance (Figure 3D). Notably, the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP/CCA exhibited the highest conductivity among the three CMP mixed systems (Figure 3E). The benzothiophene units, with the larger dipole moment, enhance intermolecular interactions and facilitate charge transfer, which is advantageous for the ORR process. The water contact angle test is a commonly employed method for evaluating the wettability of catalyst surfaces. By assessing the angle formed between a water droplet and the solid surface, the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the material surface can be determined. The result revealed that all three CMPs exhibit hydrophilic properties (Figure S4B).47 Notably, the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP demonstrated exceptional hydrophilicity, absorbing the water droplet completely within just 0.54 s of contact. This remarkable hydrophilicity aids in reducing the interfacial resistance between the electrode and the electrolyte, thereby minimizing charge and mass transfer resistances and enhancing ORR catalytic performance.

Figure 3.

Structural and electrochemical performance characterization of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA

(A) TEM spectra of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA. Scale bars represent 10 nm.

(B) The PXRD patterns of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA.

(C) Raman spectra of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, BPT-CMP/CCA, and CCA.

(D and E) (D) EIS spectra and (E) current (I)–voltage (V) curves of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to study the surface interaction between the prepared CMPs and CCA (Figures 4A and S4D−S4F). The S 2p binding energy peaks of the two structures with sulfur heterocycles comprise S 2p 3/2 and S 2p 1/2 (Figures 4B and 4C). Notably, the combination of CMPs with CCA results in the appearance of a new C 1s peak (293 eV), and causes the peaks of the elements to shift toward higher binding energy, attributable to electron transfer from CMPs to CCA. The S 2p binding energy of the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP differs by 0.4 eV from its blends, a difference larger than that of the thiophene-linked BCT-CMP (0.2 eV). Similar trends are observed in the O 1s binding energy profile (Figures 4D–4F). Specifically, the BPT-CMP and its blend systems display a larger binding energy difference of 0.5 eV for O 1s, compared to BCT-CMP (0.4 eV) and Ph-CMP (0.3 eV) systems, indicating a more significant electron transfer process. These results are primarily due to the large dipole moments, which facilitate interfacial charge transfer and enhance the kinetics of the catalytic reaction process of sulfur-containing molecules.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra and fitted results

(A) survey; S 2p of (B) BCT-CMP/CCA and BCT-CMP.

(C) BPT-CMP/CCA and BPT-CMP; O 1s of (D) Ph-CMP/CCA and Ph-CMP.

(E) BCT-CMP/CCA and BCT-CMP.

(F) BPT-CMP/CCA and BPT-CMP.

Electrochemical performance

To further clarify the improvement of thiophene linker on the ORR catalytic activity, the CMPs/CCA catalyst was tested in a 0.1 M KOH solution saturated with oxygen using a standard three-electrode system. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves at 1,600 rpm indicate that the onset potential (Eonset) of the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP/CCA is 0.93 V and its half-wave potential (E1/2) is 0.75 V, both significantly higher than those of BCT-CMP/CCA (Eonset = 0.90 V, E1/2 = 0.69 V) and Ph-CMP/CCA (Eonset = 0.88 V, E1/2 = 0.66 V) (Figures 5A, 5B, and S5A–S5C), demonstrating that the thiophene linker modulating strategy can dramatically enhance the ORR activity of the catalyst, surpassing even most metal-free polymer electrocatalysts (Figure S6C and Table S1). The thiophene-fused BPT-CMP/CCA exhibited the lowest Tafel slope of 60.3 mV dec⁻1, indicating faster kinetics compared to thiophene-linked BCT-CMP/CCA (64.3 mV dec⁻1) and model Ph-CMP/CCA (71.0 mV dec⁻1) (Figure 5C). This result is also consistent with the kinetic current density (Jk) measurements (3.01 mA cm⁻2 for Ph-CMP/CCA, 7.73 mA cm⁻2 for BCT-CMP/CCA, and 8.89 mA cm⁻2 for BPT-CMP/CCA) (Figure 5H).48

Figure 5.

Electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reaction performance

(A) LSV curves of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, BPT-CMP/CCA, and CCA.

(B) Comparison of half-wave potential and onset potential for the ORR.

(C) The corresponding Tafel plots (vs. RHE).

(D) The capacitance values of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA.

(E) Comparison of Cdl value and mass activity at 0.7 V versus RHE of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA.

(F) Long-term stability test and CH3OH-poison effect on the i–t chronoamperometric response for Ph-CMP/CCA.

(G) The electron-transfer number (n) is measured by RRDE at 1600 rpm.

(H) Performance comparison of Ph-CMP/CCA, BCT-CMP/CCA, and BPT-CMP/CCA.

(I) Galvanostatic discharge curve of BPT-CMP/CCA-based ZAB with 6.0 M KOH electrolyte and a photograph of an LED panel powered by two ZABs in series. (Data are represented as mean ± SEM. each experiment was independently tested three times; sample size n = 3; mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) was analyzed using Origin software; SD reflects the degree of dispersion among individuals samples; a small SD means that the value of the test is close to the average; the p value indicates significant differences: Ph-CMP/CCA to BCT-CMP/CCA: p < 0.0001; BCT-CMP/CCA to BPT-CMP/CCA: p < 0.0001; the statistical test was two-sided testing, the α-value was 0.05 and related p values were analyzed by a Student’s two-side test of GraphPad Prism software; p values less than 0.0001 indicate that the differences between Ph-CMP/CCA to BCT-CMP/CCA and BCT-CMP/CCA to BPT-CMP/CCA is particularly significant).

The electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was determined using cyclic voltammetry curves, providing a quantitative measure to evaluate the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of the materials (Figure 5D). As a result, the thiophene-containing CMP catalysts exhibited higher Cdl values (12.75 mF cm−2 for BPT-CMP/CCA and 10.81 mF cm−2 for BCT-CMP/CCA) compared to phenyl-containing catalytic structure (4.05 mF cm⁻2 for Ph-CMP/CCA) (Figures S5D–S5F). This trend was also observed in mass activity measured at 0.70 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) (8.13 A g−1 for BPT-CMP/CCA, 7.29 A g−1 for BCT-CMP/CCA, and 4.17 A g−1 for Ph-CMP/CCA) (Figure 5E). The Cdl and mass activity results further demonstrate that, due to non-uniform charge distribution, benzothiophene units provide superior activity density. The BPT-CMP/CCA demonstrated excellent long-term stability, with only a 7.7% loss in current density after 9 h in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, demonstrating outstanding electrochemical stability (Figure 5F). Moreover, the addition of a 3 M CH3OH solution did not significantly affect the current density, demonstrating excellent methanol resistance of BPT-CMP/CCA. After conducting stability tests, we collected the materials and performed infrared spectroscopy on them. Essentially, there were no changes observed between the obtained infrared spectra and the initial infrared spectra (Figures S1B–S1D). The electron transfer number (n) of the catalyst was gauged in an oxygen-saturated 0.1 M KOH solution using a rotating ring disk electrode. In the range of 0.2–0.6 V, the electron transfer number of BPT-CMP/CCA ranged from 3.75 to 3.80, suggesting an approximate four-electron transfer process (Figures 5G and S6A). The number of transferred electrons calculated by Koutecky-Levich plots at 0.2 V (vs. RHE) also follows the corresponding pattern (Figure S6B) The air diffusion layer with three mixed load systems was used as the air electrode for zinc-air batteries (ZABs) (Figures 5I and S7A–S7C).49,50 The BPT-CMP/CCA-based ZAB achieved a current density of 123.1 mA cm−2 at 1.0 V, and a maximum power density of 0.219 W cm−2 at 0.57 V, which exhibited excellent rate performance and voltage stability. At a current density of 5 mA cm−2, the voltage of the BPT-CMP/CCA-based ZAB maintained 1.18 V after 12 h of constant discharge, and two series-connected BPT-CMP/CCA-based ZABs successfully powered a light-emitting diode.

DFT calculations

To gain deeper insights into the distinct catalytic performance of the thiophene-modulated CMPs, DFT calculations were employed to identify specific active sites and clarify the mechanisms in their catalytic reaction process. Three theoretical models were constructed, each representing the repeating units of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP (Figures 6A−6C), respectively.51 During the calculations, we focused on BPT-CMP and evaluated its performance in catalyzing the ORR by calculating Mulliken charges and geometric parameters for key atoms along the reaction pathway (Figures 6D and 6F). The oxygen atom in O₂ interacts with the sulfur atom in BPT-CMP. Initially, the C−O bond length is measured at 1.45 Å. Subsequently, electron transfer occurs, leading to the formation of O∗ and shortening the C−O bond to 1.43 Å, thereby enhancing charge transfer between BPT-CMP and O∗. As the reaction advances further, the C−O bond length increases again to 1.46 Å, facilitating the progression of the ORR catalytic process.

Figure 6.

DFT calculations of Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP

(A–C) Optimized Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP model structures. The gray, blue, yellow, and white balls represent C, N, S, and H atoms, respectively. (D–F) The optimized geometrical structures of stationary points along the reaction pathway of BPT-CMP catalyzing ORR reaction, (D) OOH∗, (E) O∗, (F) OH∗, along with the main geometrical parameters and the Mulliken charges on main atoms.

(G) Electron localization function (Up) and orbit weight fukui function (Down, Blue, and green represent the positive and negative parts, respectively).

(H) Free energy diagrams for Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP.

(I) Activity volcanoes for the 4e− oxygen reduction reaction.

Electrophilic sites were predicted by Fukui function to identify active sites. It is worth noting that the highest distribution of the isosurface map in the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP will be more conducive to the adsorption of electrophilic oxygen intermediates (Figure 6G).52,53,54 The electron location function (ELF) further reveals that the thiophene-fused BCT-CMP and the thiophene-linked BPT-CMP enhanced larger localization around the S atom region, promoting the ORR catalytic reaction. The free-energy diagrams (ΔG) were calculated to identify overpotentials.55 The calculations indicate that the carbon atom at the 3-position of thiophene unit in BPT-CMP acts as an active site, with an overpotential of 0.58 eV (Figure 6H and Tables S2−S4). This value is lower compared to those of BCT-CMP (0.61 eV at site-3) and Ph-CMP (0.86 eV at site-3). Furthermore, when BPT-CMP adsorbs various reaction intermediates, it undergoes structural changes and surface electrostatic potential shifts that are in agreement with Gibbs free energy calculations, conforming to the four-electron reaction pathway of the ORR (Figure S7D). Additionally, the volcano plot exhibits a correlation between the overpotentials of reaction sites on Ph-CMP, BCT-CMP, and BPT-CMP (Figure 6I). These results not only identify the active sites in BPT-CMP during the catalytic ORR process but also offer valuable theoretical insights for the design and optimization of novel and high-efficiency catalysts.

Conclusions

In summary, we presented a thiophene linker modulating approach to synthesize metal-free CMP electrocatalysts featuring thiophene-fused and thiophene-linked bonding modes with unique boron β-diketone molecules. The resultant CMPs exhibited precisely tuned charge redistribution and exceptional conductivity. Notably, the thiophene-fused BPT-CMP displayed superior catalytic activity toward ORR. Based on DFT calculations and experimental analysis, the sulfur-containing heterocyclic thiophene with diversified linkers in CMPs effectively adjusts charge distribution, increases molecular dipole moments, and optimizes oxygen adsorption energy. Furthermore, these heterocyclic structures efficiently activate the neighboring sp-hybridized carbon atom (site-3) as an active site, thereby lowering the free energy, which is crucial for the catalytic reaction process. This work deepens our understanding of metal-free CMPs and demonstrates that the precise control of thiophene heterocycle linker offers a novel strategy to explore the intricate relationship between catalyst structure and catalytic activity.

Limitations of the study

The limitation of this study is that, in terms of performance alone, the prepared metal-free organic molecules still lags behind Pt-based materials. Therefore, it is still necessary to conduct more structural design and synthesis in the future to improve the ORR performance of organic catalysts.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xiaojing Long (longxj@qdu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this article will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This article does not report the original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 22375111 and 22075157), the Natural Science Foundation and Youth Innovation Team Project of Shandong Province, China (nos. ZR2024JQ037, 2021KJ018, and ZR2021YQ08), and the Taishan Scholars Program (no. tsqn201909090).

Author contributions

D.L. and B.W. contributed equally; conceptualization, B.W. and X.L.; data curation, Yali Xing and H.C.; writing–original draft, D.L. and K.Z.; writing–review and editing, X.L and B.W.; resources, K.Z.; supervision, Yanzhi Xia.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Triphenylamine | Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS#603-34-9 |

| Boron trifluoride acetic acid complex | Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS#373-61-5 |

| 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxaldehyde | Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS#3163-76-6 |

| Benzene-1,3,5-triyl tris(thiophene-2-carbaldehyde) | Shanghai Haohong Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS#2125450-22-6 |

| Benzo[1,2-b:3,4-b':5,6-b'']trithiophene-2,5,8-tricarbaldehyde | Shanghai Haohong Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS#2243590-42-1 |

| Sodium alginate | Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd | CAS# 9005-38-3 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Origin | Smith et al. | https://www.originlab.com |

| GraphPad Prism | La Jolla | RRID:SCR 002798 |

| GaussView | Semichem,Inc. | https://gaussian.com |

Method details

Synthesis

All reactions were conducted under an argon atmosphere. Tetrahydrofuran was dried using sodium or calcium hydroxide before use. Other commercially available solvents and reagents were used without further purification unless stated otherwise.

Triphenylamine Difluoroboronate Monomer: Triphenylamine (100 mg, 0.408 mmol), acetic anhydride (1.8 g, 18.36 mmol), and boron trifluoride acetic acid complex (1.15 g, 6.12 mmol) were added to a three-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was degassed for 10 minutes before introducing argon. Dry THF was subsequently added, and the reaction was conducted at 45°C for 12 hours. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was extracted with dichloromethane, and the organic phase was purified by column chromatography. The product was collected and dried under vacuum (83% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25°C) δ 8.05 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.51 (s, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H).

Ph-CMP

Triphenylamine difluoroboronate derivative (100.1 mg, 0.156 mmol), 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxaldehyde (25.3 mg, 0.156 mmol), and piperidine (0.1 mg, 0.001 mmol) were added to a three-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was degassed for 10 minutes and then backfilled with argon. Using a syringe, 6 mL of dry THF was added to the flask. The reaction mixture was stirred at 120°C for 48 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was filtered and washed with dichloromethane, water, acetone, and methanol, followed by Soxhlet extraction with THF for purification. Finally, the orange powdery polymer Ph-CMP was obtained after drying in a 60°C oven for 12 hours (83% yield).

BCT-CMP

The BCT-CMP was synthesized from benzene-1,3,5-triyl tris(thiophene-2-carbaldehyde) and triphenylamine difluoroboronate derivative following the synthesis procedure of Ph-CMP (75% yield).

BPT-CMP

The BPT-CMP was synthesized from benzo[1,2-b:3,4-b':5,6-b'']trithiophene-2,5,8-tricarbaldehyde and triphenylamine difluoroboronate derivative following the synthesis procedure of Ph-CMP (79% yield).

Preparation of carbonized calcium alginate (CCA). The as-prepared sodium alginate solution with a mass fraction of 4% was added dropwise to the 0.1 M calcium chloride solution. After 8 hours of stirring, filtering the fully cross-linked microspheres, then washed with deionized water, dried and placed in a tubular furnace, heated at 800°C for two hours under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 5°C min−1, and then naturally cooled to room temperature. The carbonized sample was soaked in 1 M hydrochloric acid and then washed with deionized water until neutral. After drying at 110°C for 6 hours, it can be finally ground into powder for later use.

Preparation of CMPs/CCA: 3 mg of CMPs and 3 mg of carbonized calcium alginate are put in a mortar, grinding for 30 minutes to mix them uniformly.

Characterizations

1H and solid-state 13C NMR spectra were tested with a Bruker AV-400 spectrometer in CDCl3 at 25°C. Chemical shifts were reported in δ ppm using CHCl3 (7.26 ppm) for 1H NMR. Thermal analysis was performed on a TG 209 instrument under nitrogen flow at a heating rate of 10°C min–1. The morphologies and structures of the samples were characterized by using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; JSM-7001F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) and the transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM–1011; JEOL Co., Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. The molecular packing was investigated by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). PXRD data were collected on a Bruker D8. Empyrean powder diffractometer using a Cu Kα source (λ = 1.5418 Å) over the range of 2θ = 2.0–40.0° with a step size of 0.02° and 2 s per step. The current (I)-voltage (V) curves were measured by a source Meter (2612B, Keithley) at room temperature. The X-ray photoelectron spectrometry (XPS) was conducted on an XPS instrument (Axis Supra). FT-IR data were performed on a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Co.). Raman spectroscopy was obtained on a Thermo Scientific DXR2 Raman spectrometer. The contact angle was measured by the Attention Optical Contact Angle measuring instrument theta (Sweden baioulin Technology Co., Ltd). To estimate pore size distributions, nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) was applied to analyze the N2 isotherm based on the model of N2@77K on carbon with slit pores and the method of non-negative regularization.

Electrochemical performance testing

All ORR measurements were conducted in Pine Research Instrumentation at ambient temperature in a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments Co., China). For the electrochemical test, 6 mg of the catalyst was dispersed in the mixture of 80 μL of Nafion solution (5 wt%), 260 μL of ethanol, and 260 μL distilled water. Then homogenous catalyst ink was obtained by an ultrasonic disperse method. 6 μL of the solution was loaded onto the glass carbon electrode (0.126 cm2). The catalyst mass loading is 0.48 mg cm‒2. Measurements were performed in a three-electrode equipped with a graphite rod counter electrode and Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The electrolytic cell radius is 3.5 cm and the electrolytic cell height is 6 cm. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments with a sweep rate of 50 mV s−1 were recorded in the potential range of 0 to −1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed in N2-saturated or O2-saturated 0.1 M aq KOH. Current-voltage curves were recorded at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 under various electrode rotation rates (400, 625, 900, 1225, 1600, 2025, and 2500 rpm, respectively). The current density was normalized to the geometrical area and the measured potentials vs. Ag/AgCl were converted to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale according to the following equation: ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.059 ∗ pH + 0.1976.

Rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) was carried out in an O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte at room temperature using a CHI760E electrochemical workstation equipped with a modulated speed electrode rotator (RRDE-3A).

A long-term stability test was conducted by measuring the current changes of the catalyst at a fixed potential of 0.6 V (vs RHE) at a rotation speed of 1600 rpm in an O2-saturated electrolyte using CHI 760 E electrochemical workstation.

Electrochemical Measurements for the Zinc-Air Battery: the air electrode was prepared by uniformly coating the as-prepared catalyst ink onto carbon paper and then drying it at 60°C for 1 h. The mass loading was 1.5 mg cm−2. A zinc plate was used as the anode. Both electrodes were assembled into a home-built electrochemical battery with the electrolyte being a 6 M KOH electrolyte.

Computational details

B3LYP hybrid density functional theory of Gaussian 09 was employed with a basis set of 6-31G (d, p). Gibbs free energy (ΔG) diagrams and charge density were calculated by Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) code. The exchange-correlation energy was modelled by using Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). The projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudo-potentials were used to describe ionic cores. The cutoff energy of 500 eV was adopted. The convergence threshold for the iteration in the self-consistent field (SCF) was set to be 10–4 eV. Denser k-points (1×1×1) were used for the electronic structure calculations. A large vacuum slab of 20 Å was inserted in z-direction for surface isolation to prevent interaction between two neighbouring surfaces. The overall ORR in an acid environment can be written as follows:

For each elementary step, the Gibbs reaction free energy G is defined as the difference between free energies of the initial and final states and is given by the expression

where is the reaction energy of reactant and product molecules adsorbed on catalyst surface, obtained from DFT calculations; and are the changes in zero-point energies and entropy due to the reaction. Each step of was obtained as follows:

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

| (Equation 3) |

| (Equation 4) |

Quantification and statistical analysis

-

1.

Pre-processing of data: XRD, LSV, CV, and other electrochemical data were converted into TXT format by the corresponding instruments, and plotted by Origin software without normalization and evaluation of outliers. Raman data were preprocessed by baseline correction. The data of SEM, TEM, contact angle, and DFT calculations were in the form of pictures or numbers, which were directly drawn by PowerPoint software without conversion, normalization, and evaluation of outliers.

-

2.

Data presentation: The electrochemical measurements were independently tested three times to avoid any incidental error. And the related error bars (presented in the form of mean ± SD) were also shown in the manuscript and supporting information.

-

3.

Sample size for each statistical analysis: The sample size of the related electrochemical measurements was three.

-

4.

Statistical methods used to assess significant differences with sufficient details: The statistical test was two-sided testing, the α value was 0.05, and related P values were analyzed by Student’s two-sided t-test and shown in the manuscript and supporting information.

-

5.

Software used for statistical analysis: The related software was Origin and Powerpoint.

Published: February 12, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112007.

Contributor Information

Binbin Wang, Email: 15689986013@163.com.

Xiaojing Long, Email: longxj@qdu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Wang Y., Li K., Cheng R., Xue Q., Wang F., Yang Z., Meng P., Jiang M., Zhang J., Fu C. Enhanced electronic interaction between iron phthalocyanine and cobalt single atoms promoting oxygen reduction in alkaline and neutral aluminum-air batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;450 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.138213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng K., Wang M., Wang B., Wang M., Wang Z., Long X. Porphyrin-containing conjugated microporous polymers with gradient asymmetric design for efficient oxygen reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024;12:11936–11944. doi: 10.1039/d3ta08064a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X., Su P., Song G., Zhou M. A critical review on regulating multi-electron pathways of oxygen reduction reaction on modified carbon-catalysts for organic wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024;488 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.150967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su C., Liu Y., Luo Z., Veder J.P., Zhong Y., Jiang S.P., Shao Z. Defects-rich porous carbon microspheres as green electrocatalysts for efficient and stable oxygen-reduction reaction over a wide range of pH values. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;406 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao L., Wang K., Lv F., Mi H., Lin F., Luo H., Guo H., Zhang Q., Gu L., Luo M., Guo S. Precise synthetic control of exclusive ligand effect boosts oxygen reduction catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:6893. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42514-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li P., Jiao Y., Ruan Y., Fei H., Men Y., Guo C., Wu Y., Chen S. Revealing the role of double-layer micro-environments in pH-dependent oxygen reduction activity over metal-nitrogencarbon catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:6936. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42749-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumeda T., Tajiri H., Sakata O., Hoshi N., Nakamura M. Effect of hydrophobic cations on the oxygen reduction reaction on single‒crystal platinum electrodes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4378. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06917-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Z., Chen C., Liu Z., Huang J., Wu M., Liu H., Li Y., Huang Y. Pt-based nanocrystal for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201808115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodama K., Nagai T., Kuwaki A., Jinnouchi R., Morimoto Y. Challenges in applying highly active Pt-based nanostructured catalysts for oxygen reduction reactions to fuel cell vehicles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021;16:140–147. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-00824-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q., Wang C., Zheng K., Wang B., Wang Z., Zhang C., Long X. Positional thiophene isomerization: a geometric strategy for precisely regulating the electronic state of covalent organic frameworks to boost oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024;63 doi: 10.1002/anie.202320037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long X., Li D., Wang B., Jiang Z., Xu W., Wang B., Yang D., Xia Y. Heterocyclization strategy for construction of linear conjugated polymers: efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:11369–11373. doi: 10.1002/anie.201905468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You Z., Wang B., Zhao Z., Zhang Q., Song W., Zhang C., Long X., Xia Y. Metal-free carbon-based covalent organic frameworks with heteroatom-free units boost efficient oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 2023;35 doi: 10.1002/adma.202209129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan X., Jia Y., Yao X. Defects on carbons for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:7628–7658. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00690j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey G., Jana R., Saifi S., Kumar R., Bhattacharyya D., Datta A., Sinha A.S.K., Aijaz A. Dual single-atomic Co−Mn Sites in metal−organic-framework-derived N-doped nanoporous carbon for electrochemical oxygen reduction. ACS Nano. 2023;17:19155–19167. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c05379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He C., Cai Y., Ma Z., Zhong X., Wang H., Li Q., Huang Y. Boron and nitrogen Co-doped molybdenum carbide nanostructures for oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021;4:8897–8905. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c01550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren J., Yan W., Liu X., Wang F., Xing Q., Xiao Z., Liu H., Chen Y., Li X. Porphyrin polymer-derived single-atom Fe assisted by Fe2O3 with oxygen updates Check for vacancy for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022;592 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M., Cao Z., Li L., Ren S. Porous Fe, N co-doped carbon with high electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reaction performance in Zn-air battery. Carbon. 2022;200:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2022.08.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun H., Zhou P., Ye X., Wang J., Tian Z., Zhu Z., Ma C., Liang W., Li A. Nitrogen-doping hollow carbon nanospheres derived from conjugated microporous polymers toward oxygen reduction reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;617:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng Y.Z., Guo G.C., Guo S., Kong L.H., Lu T.B., Zhang Z.M. Charge transfer from donor to acceptor in conjugated microporous polymer for enhanced photosensitization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:22062–22069. doi: 10.1002/anie.202109968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S., Yu H., Wang Y., Wang S., Zhang L., Zhu P., Gao C., Yu J. Exploring a Ni-N4 active site-based conjugated microporous polymer Z-scheme heterojunction through covalent bonding for visible light-driven photocatalytic CO2 conversion in pure water. Small. 2024;20 doi: 10.1002/smll.202305900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng J., Wan S., Cao S. Promoting solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production over thiazole-based conjugated polymers via generating and converting singlet oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62 doi: 10.1002/anie.202310476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Y., Cui F., Rong H., Song J., Jing X., Tian Y., Zhu G. Continuous porous aromatic framework membranes with modifiable sites for optimized gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202113682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao L., Dai Y., Zhang Y., Liu B., Guo P., Zhang Z., Shen L., Zhang N., Zheng Y., Zhang Z., et al. Atomically dispersed p-block aluminum-based catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024;63 doi: 10.1002/anie.202402657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dochain S., Vetica F., Puttreddy R., Rissanen K., Enders D. Combining organocatalysis and lanthanide catalysis: a sequential one-pot quadruple reaction sequence/hetero-diels-alder asymmetric synthesis of functionalized tricycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:16153–16155. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mo W., Zhu Z., Kong F., Li X., Chen Y., Liu H., Cheng Z., Ma H., Li B. Controllable synthesis of conjugated microporous polymer films for ultrasensitive detection of chemical warfare agents. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5189. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32878-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razzaque S., Guo L., Weng J., Su L., Tan B. Facile fabrication of hypercrosslinked microporous polymer nanospheres for effective inhibition of triple negative breast cancer cells proliferation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;620:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z., Gao Y., Zuo L., Long C., Yang C., Zhang X. Tailoring heteroatoms in conjugated microporous polymers for boosting oxygen electrochemical reduction to hydrogen peroxide. ACS Catal. 2023;13:4790–4798. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.2c06092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W., Zuo H., Cheng Z., Shi Y., Guo Z., Meng N., Thomas A., Liao Y. Macroscale conjugated microporous polymers: controlling versatile functionalities over several dimensions. Adv. Mater. 2022;34 doi: 10.1002/adma.202104952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma H., Chen Y., Li X., Li B. Advanced applications and challenges of electropolymerized conjugated microporous polymer films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31 doi: 10.1002/adfm.202101861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W., Wang K., Wang C., Liu W., Pan H., Xiang Y., Qi D., Jiang J. Mixed phthalocyanine-porphyrin-based conjugated microporous polymers towards unveiling the activity origin of Fe–N4 catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6:22851–22857. doi: 10.1039/c8ta08173e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang Z., Wang H.Y., Zheng H., Zhang W., Cao R. Porphyrin-based frameworks for oxygen electrocatalysis and catalytic reduction of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:2540–2581. doi: 10.1039/d0cs01482f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhunia S., Peña-Duarte A., Li H., Li H., Sanad M.F., Saha P., Addicoat M.A., Sasaki K., Strom T.A., Yacamán M.J., et al. [2,1,3]-benzothiadiazole-spaced Co-porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks for O2 reduction. ACS Nano. 2023;17:3492–3505. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c09838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi J.D., Xu R., Wu Q., Zhang T., Zang K.T., Luo J., Liang Y.L., Huang Y.B., Cao R. Atomically dispersed iron−nitrogen active sites within porphyrinic triazine-based frameworks for oxygen reduction reaction in both alkaline and acidic media. ACS Energy Lett. 2018;3:883–889. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Wang N., Lei H., Li X., Zheng H., Wang H., Zhang W., Cao R. Bioinspired N4-metallomacrocycles for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reaction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021;442 doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hao Y., Zhang X., Yang Q., Chen K., Guo J., Zhou D., Feng L., Slanina Z. Highly porous defective carbons derived from seaweed biomass as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction in both alkaline and acidic media. Carbon. 2018;137:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2018.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang B., Qin L., Fang Y., Chai Y., Xie X., Lu B., Liang S., Zhou J. Tuning Zn2+ coordination tunnel by hierarchical gel electrolyte for dendrite-free zinc anode. Sci. Bull. 2022;67:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2022.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia J., Wang Z., Rodrig N.D., Nan B., Zhang J., Zhang W., Lucht B.L., Yang C., Wang C. Super-reversible CuF2 cathodes enabled by Cu2+-coordinated alginate. Adv. Mater. 2022;34 doi: 10.1002/adma.202205229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji D., Park J.M., Oh M.S., Nguyen T.L., Shin H., Kim J.S., Kim D., Park H.S., Kim J. Superstrong, superstiff, and conductive alginate hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poon C.T., Wu D., Lam W.H., Yam V.W.W. A solution-processable donor–acceptor compound containing boron(III) centers for small-molecule-based high-performance ternary electronic memory devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:10569–10573. doi: 10.1002/ange.201504997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X., Guo A., Fu Y., Tan M., Luo W., Yang W. Porphyrin-conjugated microporous polymer nanospheres as electrocatalysts for nitrobenzene detection and oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023;6:3226–3235. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.2c04811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao G., Ding Z., Li F., Li Y.X., Wang X.L., Yao Y.F. Well-dispersed ZIF-derived N-doped carbon nanoframes with anchored Ru nanoclusters as HER electrocatalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47:14836–14846. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.02.227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macedo L.J.A., Lima F.C.D.A., Amorim R.G., Freitas R.O., Yadav A., Iost R.M., Balasubramanian K., Crespilho F.N. Interplay of non-uniform charge distribution on the electrochemical modification of graphene. Nanoscale. 2018;10:15048–15057. doi: 10.1039/c8nr03893g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z., Zhu Y., Chen X., Zhang H., Wang J. A full-spectrum metal-free porphyrin supramolecular photocatalyst for dual functions of highly efficient hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201806626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X., Zhang F., Wang Y., Xiong K., Lang X. Extending the 2D conjugated microporous polymers linked by thiazolo[5,4-d]thiazole for green light-driven selective aerobic oxidation of amines. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022;10:14965–14975. doi: 10.1039/d2ta02603a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren F., Wang F., Pan Y., Sun H., Zhu Z., Ma C., Xiao C., Liang W., Chen L., Li A. Flexible and UV resistant films based on thiophene-substituted conjugated microporous polymers bearing alkyl chains: tuning of rigidity into soft. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2018;303 doi: 10.1002/mame.201700619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma B.C., Ghasimi S., Landfester K., Zhang K.A.I. Enhanced visible light promoted antibacterial efficiency of conjugated microporous polymer nanoparticles via molecular doping. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016;4:5112–5118. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00943c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang G.R., Munoz M., Etzold B.J.M. Accelerating oxygen-reduction catalysts through preventing poisoning with non-reactive species by using hydrophobic ionic liquids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:2257–2261. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong Y., Li H., Gong X., Han C., Song P., Xu W. Research progress of non-Pt-based catalysts in cathode oxygen reduction reaction of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2023;40:1077–1093. doi: 10.3390/catal14090569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun W., Wang F., Zhang B., Zhang M., Küpers V., Ji X., Theile C., Bieker P., Xu K., Wang C., Winter M. A rechargeable zinc-air battery based on zinc peroxide chemistry. Science. 2021;371:46–51. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang T., Zhang S., Li L., Hu Y., Liu X., Lee J.Y. Self-decoupled oxygen electrocatalysis for ultrastable rechargeable Zn-air batteries with mild-acidic electrolyte. ACS Nano. 2023;17:17476–17488. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c05845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu M., Yang S., Yang X., Cui C.X., Liu G., Li X., He J., Chen G.Z., Xu Q., Zeng G. Post-synthetic modification of covalent organic frameworks for CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3800. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39544-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu H., Li L., Chen H., Xing Y., Wang Z., Zhang C., Long X. Topology control of covalent organic frameworks with interlaced unsaturated 2D and saturated 3D units for boosting electrocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024;63 doi: 10.1002/anie.202410719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen H., Wang C., Wu H., Li L., Xing Y., Zhang C., Long X. Host-guest-induced electronic state triggers two-electron oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:9222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-53714-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B., Xing Y., Zhang K., Wang Z., Xia Y., Long X. Electron-deficient organic molecules based on B←N unit: a n-type room-temperature chemiresistive sensors with moisture resistance. Adv. Sci. 2024;11 doi: 10.1002/advs.202409890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang F., Su P., Guharoy U., Ye R., Ma Y., Zheng H., Jia Y., Liu J. Edge-enriched N, S co-doped hierarchical porous carbon for oxygen reduction reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023;34 doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this article will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This article does not report the original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.