Abstract

This study presented the development and evaluation of an integrated image-guided robotic system for hair transplant surgery. A novel surgical robot was designed, incorporating an image-guided system, a dual-function needle mechanism, and a comprehensive robotic system capable of performing both follicle harvesting and implantation in a unified setup. The robot comprised three main subsystems: the image-guidance system, the dual-function needle, and the robotic hardware. Each subsystem was meticulously developed and individually described, detailing the specific processes and mechanisms involved. Experimentation involved a silicone phantom embedded with filaments to mimic real human hair density, providing a realistic simulation for testing. The image-guided system demonstrated high precision in detecting the positions of hair follicles, achieving an accuracy rate of 89 %. Meanwhile, the dual-function needle proved effective in executing both the harvesting and implanting functions, achieving harvest and implant success rates of 83.3 % and 53.3 %, respectively. It was important to note, however, that the suction system integrated into the needle mechanism did not function as intended. Further simulations conducted on the robotic system affirmed its suitability for a wide range of head sizes, specifically those with a breadth diameter between 113 and 179 mm, effectively encompassing most of the Asian demographic. This integration of advanced robotics and image-guidance aimed to enhance the efficacy and precision of hair transplant procedures.

Keywords: Dual-function needle mechanism, Follicular unit extraction (FUE), Image-guided system, Hair transplant surgery, Surgical robot

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Hair loss is a prevalent issue that impacts millions globally, with a variety of causes ranging from hereditary factors to lifestyle choices [1], [2], [3]. Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is a significant contributor to hair thinning, affecting both men and women by altering the balance of Testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the hair growth cycle [4], [5]. It is estimated that approximately 85 % of men and 40 % of women experience hair loss, which can lead to diminished self-confidence and social anxiety [6], [7]. The quest for effective treatments has spurred advances in hair transplant techniques, evolving from the rudimentary procedures of the past to modern, sophisticated surgeries that offer renewed hope to those affected [8], [9].

The origins of hair transplant surgery trace back to 1937 with the pioneering work of Japanese doctor Shoji Okuda [10]. Over the decades, the procedure has evolved significantly, with modern techniques such as strip harvesting and follicular unit extraction (FUE) enhancing both the safety and effectiveness of the treatment [11], [12]. These methods accommodate various hair characteristics, such as type and curliness, and consider anatomical differences in potential donor sites [13], [14], [15]. Despite these advancements, hair transplantation remains a labor-intensive process requiring high precision, which can induce significant fatigue among surgeons [16], [17]. This has led to the integration of robotic systems in surgical workflows to enhance precision, reduce surgeon fatigue, and replicate the process with high fidelity.

One of the latest advancements in this field is the development of an integrated image-guided robotic system for hair transplant surgery [18], [19], [20]. This system represents a significant leap forward, aiming to streamline the hair transplant process and reduce the variability associated with human operators [21], [22], [23]. The primary goal of this research was to develop and evaluate an integrated system that incorporates several key technological innovations. These include an advanced image-guidance system, a dual-function needle mechanism capable of performing both harvesting and implanting tasks, and a robust robotic platform [1], [24]. By automating critical steps of follicle harvesting and implantation, the system seeks to improve both the efficiency and outcomes of hair transplant surgeries [25], [26], [27].

The development of an integrated image-guided robotic system for hair transplant surgery represents a significant advancement in robotic-assisted surgical technology. This system uniquely combines advanced robotic design, real-time image guidance, and a dual-function needle mechanism into a single, cohesive setup. Existing robotic systems for hair transplant procedures typically focus on either follicle harvesting or implantation; however, this new approach integrates both functions seamlessly. The dual-function needle mechanism is particularly innovative, allowing the system to switch between harvesting and implantation without manual intervention. This reduces the overall procedure time and minimizes handling of delicate follicles, potentially increasing the viability of transplanted hair. The robotic system is also designed to accommodate a wide range of head sizes, specifically those within the Asian demographic, making it highly adaptable to a diverse patient population [28], [29], [30], [31].

The system's architecture revolves around three main subsystems: the robotic hardware, the image-guidance system, and the dual-function needle mechanism. The robotic hardware includes mechanical and control elements that enable precise follicle extraction and implantation, which were validated through simulations and experiments using a silicone phantom [1]. This phantom, embedded with filaments to mimic human hair density, provided a realistic yet controlled environment for testing, ensuring reliable performance metrics without ethical or logistical challenges associated with initial human trials [32], [33]. The image-guidance system plays a crucial role in the system’s functionality, utilizing advanced imaging technologies to accurately detect and localize hair follicles with an accuracy rate of 89 %. This capability allows the robotic arm to target and extract follicles with minimal tissue damage, enhancing the overall precision and efficacy of the procedure [34].

The dual-function needle mechanism is a groundbreaking feature of the system. It enables seamless transitions between harvesting and implantation, eliminating the need for manual adjustments during the procedure. This dual functionality not only reduces the time required for surgery but also minimizes the risk of damage to follicles, thereby improving the success rates of both follicle harvesting and implantation [35], [36]. Experimental results demonstrated harvest and implant success rates of 83.3 % and 53.3 %, respectively, underscoring the potential of the mechanism to address critical challenges in robotic hair transplant systems.

The field of robotic systems for hair transplant surgery is still emerging, offering significant opportunities for advancements in precision, efficiency, and adaptability to diverse demographics [1], [37], [38], [39]. The integrated image-guided robotic system presented addresses critical challenges such as time-intensive manual interventions, limited follicle localization accuracy, and the absence of a unified setup for harvesting and implantation. Featuring a dual-function needle mechanism and advanced image-guidance, it is designed to accommodate diverse head sizes, particularly within the Asian demographic [40], [41]. As clinical testing progresses, this technology is expected to revolutionize hair transplant surgeries, offering improved care and addressing growing global demands. Autonomy is a critical feature of the proposed robotic system, enabling precise hair follicle harvesting and implantation with minimal human intervention. Inspired by established methodologies, the system employs a hierarchical framework encompassing perception, decision-making, control, and validation. Real-time RGBD imaging and preprocessing techniques, including region-of-interest masking and Hough Line Transform, ensure accurate follicle detection [42], [43].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design approach

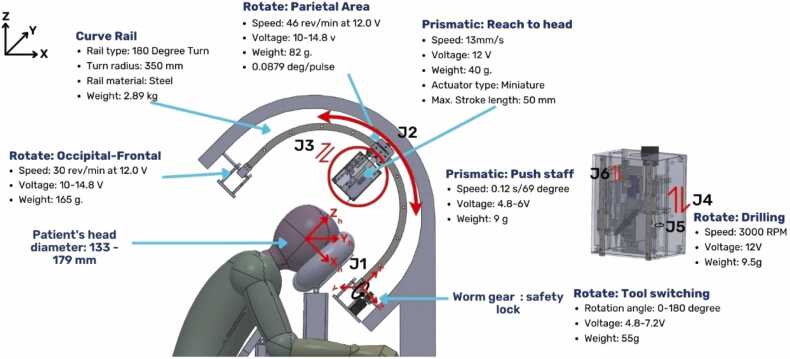

The proposed hair transplant robotic system was conceptualized and developed specifically for this study to address key challenges in existing robotic hair transplant methods. The system comprises three essential subsystems: the robotic mechanism, the image-guidance system, and the dual-function needle mechanism. These components were designed to function cohesively, enabling precise and efficient hair follicle harvesting and implantation. The image-guidance system plays a pivotal role in obtaining accurate graft positions, allowing the robotic mechanism to perform targeted harvesting and implantation with high precision. The needle mechanism integrates both harvesting and implantation functions, enabling seamless transitions between the two tasks without manual intervention. The robot's primary motion involves repeated back-and-forth movements between the donor and recipient areas, guided by the image-guidance system to ensure accurate execution of the procedure. This novel design is depicted in Fig. 1, showcasing the integration of these subsystems into a unified robotic system tailored for hair transplant applications.

Fig. 1.

The overview and conceptual design of the hair transplant robot mechanism.

The robot system incorporates six joints, three of which are rotational and three are prismatic in nature. Joint J1 enables the rotation of the curve rail, allowing the robot to move left and right. Joint J2 facilitates the carriage's movement along the curve rail. Joint J3 controls the prismatic motion of the needle slot. Joint J4 maneuvers the harvesting needle, guiding it to punch into the scalp. Joint J5 handles the drilling of the harvesting needle and incising of the tissue. Lastly, Joint J6 pushes the staff to implant the hair graft accurately.

2.2. Robotic system

The robotic system incorporates six degrees of freedom (DoFs) to enable a range of movements, including front-and-back, lateral, prismatic, and rotational motions, as illustrated in Fig. 2. A curve guide rail facilitates repetitive needle slot carriage movements between the donor area (occipital region) and recipient area (frontal region). Joint flexibility allows tilting of the guide rail to access lateral angles, while vertical motions and drilling actions are supported by the last two joints for harvesting and implantation. The robot's workspace was designed to accommodate head breadth diameters ranging from 113 to 179 mm [44], consistent with Asian population data. Considering that the average spacing between hair follicles is 1–1.4 mm [45], a movement resolution of ± 1 mm was established as a design requirement to ensure precise targeting of individual follicles.

Fig. 2.

Overview of kinematics of the hair transplant robot.

The size of the robot's curve rail is determined by three key factors: the patient's head diameter, the needle slot length (23.8 cm), and the difference between the needle tip and the patient's head (7.5 cm). To obtain the patient's head diameter, the equation 2πr is applied, where r represents the maximum measurement of head circumference (OFC). For this robot's design, we used an input OFC value of 60 cm, resulting in a head diameter of 40 cm. The curve rail diameter is obtained by adding the patient's head diameter (pd), needle slot length (nl), and the difference between the needle tip and the patient's head (nh). The calculated curve rail diameter size is 350 mm (Curve rail diameter=pd+nl+nh). The modified robot system will consist of 5 Degree of Freedom (DoF) joints and a camera system for one operating cycle is explained in Fig. 3. The RGB (Red, Green, Blue) imaging system in Fig. 3. provides color data to facilitate precise identification and mapping of critical components in the robotic system. Specifically, Red is used to indicate rail movement, Green represents both the harvest and implant needle placements, and Blue corresponds to the patient’s head. This color-coded approach enhances the system’s ability to segment and localize each element effectively during operation, ensuring accurate and efficient robotic actions.

Fig. 3.

Working process overview of the developed hair transplant robot.

The first joint (J1) will be able to rotate around the Z-axis to allow the robot to access the lateral angles of the patient's head. The second joint (J2) will be located on the robot frame, enabling the mobility slot that contains the punch needle to move freely along the robot frame. This joint will allow the robot to access the frontal plane of the donor and the recipient. J1 and J2 will be the main joints that will localize the punch needle location to target the hair graft position in the hair transplant process. The camera system consists of an RGB camera and a Depth camera. The data from both cameras will be processed by the image processing program. The harvesting and implantation process will be controlled. Joint (J3) is located along the punch needle axis and is responsible for punching through the hair scalp of the patient in the donor area to harvest the image-targeted hair graft. On the other hand, Joint (J4) will be responsible for rotating the punch needle to cut the hair graft tissue surrounding it before harvesting it. The removed graft will be stored within the punch needle tube and transferred to the final implant location.

The punch needle engages in the scalp layer and harvests the graft with the help of J3 and J4. The force sensor will receive the feedback and send it back to the robot control system to ensure appropriate depth was applied during the engagement. After the target graft is harvested and stored within the punch needle tube tip, the needle tip will relocate to the home position by J3 before the mobility slot will move from the donor area to the recipient area by J2. The implantation process starts from the penetration of the destination with the needle tip before the graft is inserted into the hole. The stylet will push the graft within the needle into the hole by a retraction of Joint (J5) to the hollow needle.

2.3. Image-guided system

The overview of the image-guided system used by the robot to detect hair graft positions is depicted in Fig. 4. The image-guided system of the robot comprises two main components: a stereo depth camera and an image processing program. The depth camera delivers real-time video stream inputs, providing both color and depth streams to the image processing program. The aligned color and depth streams undergo a Region of Interest (ROI) mask application and are then converted into grayscale for edge detection. Subsequently, the probabilistic Hough line transform is applied to the color stream. The positions of the graft line endings detected on the color stream are reprojected to determine the camera reference location in the depth frame. The image processing results yield camera reference coordinates in the x, y, and z (depth) directions [46], [47], [48]. The depth value obtained from this process is measured in meters and then converted into millimeters for length calculation. Under specific conditions, the shaft and root ends are determined based on depth values, where the ending point with less depth is considered the hair shaft, while the ending point with greater depth is identified as the root end.

Fig. 4.

The conceptual design of the Imaging system.

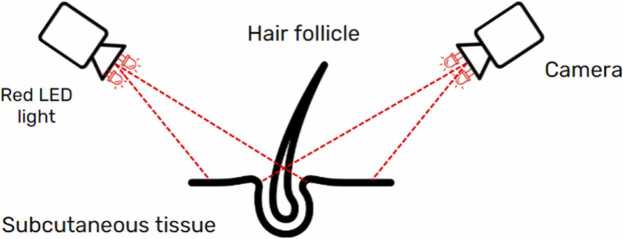

To enhance the efficiency of the previous hair transplant robot, the visualization system of the robot needs improvement. Misalignment of the needle insertion line and the hair follicles during the harvest process causes transactions [49]. The image from the visualization system guides the robot to perform precise operations. Additionally, the proposed design aims to prevent damage to hair follicles during the harvest process and provide guidelines for the direction and position of hair transplant surgery shown in Fig. 5. The imaging system consists of a camera and red LED light with the Raspberry Pi4 microprocessor for fetching real-time video streams. The camera provides colored images of objects and displays the hair structure and hair follicles of the donor site and recipient area. The obtained image from the camera is used as an input image for image processing to identify the position of each hair follicular unit in the next step. The red LED light attaches to the camera to omit the bruises and blood on the scalp for better visualization during surgery.

Fig. 5.

The image-guided system used by the robot to detect hair graft positions.

Since the imaging system could not visualize the hair follicles underneath the dermis layers, the angle of the follicles is a crucial requirement for the harvest process. An investigation shows the range of angle differences between hair shafts on the surface of the epidermis and hair follicles, ranging from 2.8 to 40.3 degrees and 12.8 degrees on average. The imaging system starts by receiving the video input from the RGBD camera fetching real-time video streams, both depth frame and color frame. The color frame is passed to the preprocessing function to prepare the image for the segmentation phase, including marking the region of interest (ROI) and grayscale conversion. Hair is detected using Hough Line Transform to obtain the shaft and base of the hair grafts from the color frame video stream. The base of the hair graft assumes to have a longer distance from the camera system. The graft orientation is calculated from the 3D spherical coordinates and gives the graft orientation in the form of a rotation matrix (3 ×3).

2.4. Needle mechanism

Structural overview of the proposed robotic system shown in Fig. 2 illustrates its six degrees of freedom (DoF), including prismatic and rotational motions, the curved guide rail enabling back-and-forth transitions, and the integration of the needle mechanism for follicle harvesting and implantation. Fig. 6. depicts the developed needle mechanism and its component. The needle mechanism can be categorized into two components: the harvesting mechanism and the implanting mechanism. This developed needle mechanism is based on the tools used in hair transplant surgery, with both the harvesting and implanter needles having a diameter of 0.9 mm. Notably, the grafts are harvested and implanted individually, eliminating the need for storing them in a reservoir or complex tool changing.

Fig. 6.

The developed needle mechanism and its component.

The needle mechanism consists of two servo motors, a Direct Current (DC) gear motor, and a microcontroller-controlled suction pump. The process commences with the tool-switching servo motor positioned at 135° for the harvesting needle, while the DC gear motor manages the drilling action to dissect the graft from adjacent tissues and muscles of the harvesting needle. Subsequently, the DC motor halts the drilling, and the tool-switching servo motor moves to 35° to switch from the harvesting needle to the implanter needle [50]. During this time, the suction system engages, extracting the hair graft into the implanter needle. Once the robot positions the needle slots at the recipient sites, the graft can be implanted efficiently. Fig. 7. displays the sequential steps involved in the functioning of the needle slot for both hair harvesting and implantation processes.

Fig. 7.

The functioning of the needle slot for both hair harvesting and implantation processes. (a) The needle slot harvest needle is positioned at the target position. (b) With precision, the implanter is positioned and gently pressed onto the graft. (c) The implanter pen moves to the recipient site (d) Using the rack and pinion mechanism, ensuring smooth and precise implantation of the graft.

Fig. 7 (a) explains about the needle slot harvest needle is positioned at the target position. The punch needle drills down at 3000 rpm from the DC gear motor and dissects the graft from adjacent tissue. With precision, the implanter is positioned and gently pressed onto the graft. The activation of the suction system efficiently relocates the graft up into the implanter needle is shown in Fig. 7 (b). The implanter pen moves to the recipient site and is pressed down 4 mm as shown in Fig. 7 (c). Using the rack and pinion mechanism, which is powered by the servo motor, the staff is steadily pushed, ensuring the smooth and precise implantation of the graft is shown in Fig. 7 (d). Once the process is completed, the rod and implanter are carefully pulled up, signifying the successful completion of the implantation. The needle slot was securely attached to the aluminum frame, with the fabricated silicone phantom positioned beneath it. The needle was properly sealed and connected to the vacuum system to relocate the hair graft up into the implanter needle. The needle mechanism system was controlled via a microcontroller circuit, receiving user input from the laptop, while the vacuum system was manually operated by turning the vacuum pump switch on and off. To assess the effectiveness, the suction system was activated for a brief duration to observe if the graft successfully relocated into the implanter needle. Needle mechanism experimental setup with the needle slot attached to the aluminum frame positioned above the phantom is shown in Fig. 8. The needle was sealed and connected to the vacuum system for relocating the hair graft up into the implanter needle. The needle mechanism system is controlled using a microcontroller circuit while the vacuum system is controlled manually.

Fig. 8.

Experimental setup with the needle slot attached to the aluminum frame positioned above the phantom.

The experiment was divided into three setups: harvesting function, suction function, and implanting function as shown in Fig. 9. The microcontroller receives user commands manually entered from the laptop for each step, following the target positions selected by the user. The harvesting function was tested first, and if it proved successful, it was then used to test the suction function. Subsequently, the implanting function was tested separately. In all cases, the experiment yielded successful results based on the predefined criteria.

Fig. 9.

The overall experiment procedure for needle mechanism with harvest, implant and function.

The harvest needle slot aiming at the target hair graft ready to perform the harvesting function as shown in Fig. 10. The harvesting experiment began by positioning the needle slot precisely at the target hair graft. The tool-switching servo motor was set at 135°, activating the DC motor at 3000 rpm while moving the needle slot to punch and drill down 4 mm into the silicone layer of the phantom to dissect the graft. Following this, the needle slot moved upward, and the DC motor was deactivated before the results were observed. The criteria for a successful graft dissection were as follows: the graft was completely dissected from the phantom, not adhered to the needle, not embedded into the silicone layer, and did not detach from the silicone. The suction system will be tested by successfully extracting the graft from the donor area. To create a vacuum condition, the implanter needle was sealed at the end with the suction tube as shown in Fig. 11 (a). The needle slot was then positioned above the dissected graft, and the tool-switching servo motor was set at 35° for the implanter needle. Upon activating the suction system for a couple of seconds, the graft relocated into the implanter needle. The success of the suction system was determined by the graft effectively relocating into the implanter needle and staying in place without falling off.

Fig. 10.

The harvest needle slot aiming at the target hair graft ready to perform the harvesting function.

Fig. 11.

(a) The vacuum-sealed implanter needle connecting to an external suction system. (b) The prototype needle slot with an implanter needle aiming to implant the filament into the phantom that is placed on the holding base.

The needle slot was positioned at the recipient site (Fig. 11. (b)), and the tool-switching servo motor was set at 35° before inserting the filament into the implanter needle. The needle slot moved downward until the implanter needle reached a depth of 4 mm into the silicone layer. The micro servo motor was then positioned at 135° to push the staff inside the implanter needle, implanting the filament into the silicone phantom. Subsequently, the servo motor switched to 90° to retract the staff and leave the filament securely in place.

3. Experiments and result

The experiments conducted in this study were designed to evaluate the performance of the proposed integrated image-guided robotic system for hair transplant surgery, which incorporates an image-guidance subsystem, a dual-function needle mechanism, and robotic hardware. These components were tested under controlled laboratory conditions to validate their ability to perform both follicle harvesting and implantation tasks. A silicone phantom embedded with filaments was used to simulate the mechanical and spatial properties of real human hair, providing a realistic yet controlled environment for assessing the system's functionality. The filaments were selected based on their similarity to human hair in terms of density, elastic modulus, and stiffness. Nylon filaments were chosen for their density of approximately 1.15 g/cm³ , elastic modulus of 2.4 GPa, and stiffness of 5.6 N/mm, closely approximating the properties of human hair, typically characterized by a density of 1.32 g/cm³ , an elastic modulus ranging from 2 to 4 GPa, and stiffness values of 3–6 N/mm depending on hair type and condition. While slight deviations exist, nylon was selected for its availability, uniformity, and ease of integration into the silicone phantom, ensuring a realistic simulation of the forces and behaviors encountered during follicle harvesting and implantation. Key performance metrics, including follicle localization accuracy, harvesting success rate, and implantation success rate, were measured and analyzed. The experiments were complemented by simulations using MATLAB's Robotic System Toolbox™ to validate the robot's workspace and movement precision. This approach enabled the experimental outcomes to approximate real-world conditions while maintaining consistency and reproducibility in testing.

3.1. Robot workspace identification

The design and functionality of the robot were rigorously evaluated using a simulation model and MATLAB's Robotic System Toolbox™ [51]. The primary objective was to calculate the robot's reachable and dexterous workspace, essential for ensuring its effective performance in practical applications. The robot model was carefully constructed within the MATLAB environment, employing joint parameters to simulate realistic movement. However, the process was not without challenges. The MATLAB toolbox, while comprehensive, lacked direct support for simulating the curve rail motions of specific joints, notably J1 and J2. To overcome this limitation, creative manipulations were necessary, involving the creation of substitution joints that could replicate the required curve rail motions. This modification allowed the accurate simulation of the robot's movements and capabilities.

The robot model comprised five distinct links, each contributing to the overall range of motion and dexterity of the system. The reachable workspace of the robot was calculated by generating a large number of random joint configurations, all within the predefined constraints of joint movement. Specifically, 10,000 sample points of joint configurations were generated to thoroughly assess the robot's workspace. These configurations were plotted to visualize the extent of the robot's reach, with the results displayed as a series of blue dots representing the potential positions of the robot's end-effector.

In addition to this, the simulation incorporated a red sphere mesh to represent the patient's head location, a critical target area for the robot's operations as shown in Fig. 12. The sphere was sized with a diameter of 150 mm, reflecting the average head breadth of Asian populations, as cited in relevant anthropometric studies. This visualization was crucial for demonstrating the robot's capability to effectively cover the intended workspace, ensuring that it could operate within the constraints posed by the physical dimensions of the patient's head. Fig. 13 presents the simulation results of the robot’s reachable workspace, visualized using MATLAB's Robotic System Toolbox™. The blue dots indicate all the points within the robot's operational range, while the red sphere represents the optimal positioning of the patient’s head during hair transplant procedures. The robot's workspace is configured as a half-sphere to align with the standard downward-facing posture adopted by patients during hair transplant surgeries. This configuration ensures ergonomic efficiency while allowing the robot to access both donor and recipient areas effectively.

Fig. 12.

The simulation of the robot’s reachable workspace using MATLAB Robotic System Toolbox with blue dots representing reachable workspace and red sphere representing the patient’s head.

Fig. 13.

Simulation results showing the robot’s workspace with blue dots representing reachable points and the color palette indicating workspace density.

The dense clustering of blue dots near the central region of the curved rail demonstrates the robot's ability to perform precise and repetitive movements in the optimal target zone. This concentration indicates the ideal placement for the patient's head, ensuring that follicle harvesting and implantation tasks are carried out with minimal deviation and maximum accuracy. The simulation confirms the robot's capability to meet the workspace requirements for the Asian population, with head breadth diameters ranging between 113 and 179 mm, as specified in the design. The results also validate the robot's movement resolution of ± 1 mm, a critical factor for targeting individual hair follicles spaced 1–1.4 mm apart. The robot achieves this level of precision through its six degrees of freedom, enabling front-and-back, lateral, prismatic, and rotational movements, as well as tilting and vertical motions. These capabilities allow the robot to handle complex trajectories while maintaining high accuracy, which is essential for minimizing damage to adjacent follicles and surrounding tissue. Overall, the simulation demonstrates the robot's adaptability and precision within a defined workspace, supporting its clinical applicability in hair transplant surgery.

3.2. Image-guided system

The experimental setup of the image-guided system and the screen display of the program results are shown in Fig. 14. (a). The image-guided system underwent testing using a fabricated skin silicone phantom (RA001AB), along with a black filament protruding approximately 2 mm, with a graft density of 40 grafts per mm2, mimicking the donor area. The silicone was affixed to a foam sphere with a diameter of 15 cm, emulating the patient's head. To achieve the best position within the limitations of curve rail size and camera specifications, the depth camera was fixed at approximately 25 cm from the phantom's base. The camera was connected to a laptop using a USB (Universal Serial Bus) cable, and an image processing program was employed. The monitor displayed the detected hair graft location coordinates in the video stream window, with a green line highlighting the features, and the coordinates were shown in the terminal tab.

Fig. 14.

(a) The experimental setup of the image-guided system and the screen display of the program results (b) image segmentation process of hair grafts.

Part of the image segmentation process of hair grafts is to acquire the position in the array format with the unit in the image pixel shown in Fig. 14. (b). The user interface (UI) was able to receive the threshold value from the user and use it as the threshold for inverse binary thresholding after noise reduction. The threshold image will be used to find the red contour line and segmented by using a green rectangular box and return the position values in the array and image side by side to the original image in the resulting Fig. 15. (a). It has shown that this method was able to omit the overlaying hair lines and able to recognize the standard hair shaft length follicular unit with 2 mm. height sustainably. The maximum number of hair grafts harvesting per frame should not exceed 20–30 % of the total number of grafts within the harvesting site. This action will prevent the harvesting site hair from looking thinner. The software algorithm will randomize 3 positions of detected hair grafts and create a triangle before selecting the 2nd triangle point coordinate as the harvesting position Fig. 15. (b). The graft positions which are close to the prior triangle coordinates will be eliminated from the randomized algorithm and the process is repeated until the target number of grafts was acquired.

Fig. 15.

Image segmentation process (a) Implantation site detection (b) Harvesting position detection (Green dots) (c) Receiving implantation sites (Red dots).

The prototype software is used to receive the implantation sites input from the surgeon. This allows the user to select the implantation site frame images via the open menu and add the mark to signify the target decision in the image frame before saving the result with the save menu. The site positions will be detected via another program. The program will detect the resulting image from the receiving implantation site program using the color thresholding and contour segmentation as shown in Fig. 15.(c). The green and red dots observed on the keyboard background result from initial edge detection and segmentation processes, which sometimes misclassify non-hair features. To address this, the system employs region-of-interest (ROI) masking to limit detection to the scalp area, effectively excluding background elements. Additionally, edge detection parameters and post-processing filters are optimized to minimize interference from non-hair features while maintaining high accuracy for follicle detection. These measures ensure that background detections do not adversely affect the overall system performance, as only features within the ROI are considered for further processing. The image-guided system successfully detected the location of the filaments. However, in some cases, certain filaments were not detected due to their perpendicular angle towards the camera, causing them to appear as dots or extremely short line segments that did not meet the detection criteria. For the filaments to be detected, they needed to exhibit a line feature and be long enough to be recognized by the probabilistic Hough line transform. Additionally, the detected line segments must display depth differences between the shaft ending and the base end, indicating that they are not lying flat on the surface and can be considered as hair grafts.

3.3. Needle mechanism

To evaluate the needle mechanism under controlled experimental conditions, the ABB Yumi robot was utilized as a precision-controlled platform. The ABB Yumi robot was selected for its collaborative dual-arm design, high accuracy, and flexibility, which made it ideal for replicating the manual actions of a surgeon during hair harvesting and implantation tasks. Its stability and precise motion capabilities ensured consistent and repeatable testing of the needle mechanism. The experimental setup involved equipping the needle mechanism with two servo motors and a DC gear motor, controlled by an Arduino UNO board programmed with predefined functions. The ABB Yumi robot held and navigated the needle slot to perform the punching action on a silicone phantom, mimicking the hair follicle extraction process at the donor area. The extracted follicles were then transferred and implanted into the recipient area, as shown in Fig. 16 (a) and (b).

Fig. 16.

Harvesting process (a) The needle mechanism for testing harvesting (b) Recipient area and implanting of the hair grafts on the silicone phantom.

Although the ABB Yumi robot is not part of the final integrated system, its inclusion in this experiment was crucial for accurately assessing the performance of the needle mechanism. By simulating the actions of a surgeon, the ABB Yumi robot provided a reliable and repeatable testing platform, enabling precise evaluation of the needle’s ability to perform both harvesting and implantation functions. This setup allowed the research team to validate the mechanism’s functionality before integration into the comprehensive robotic system.

Table 1. outlines the motor control settings for a needle mechanism experiment involving a DC motor and two servo motors during harvesting, suction and implantation processes. The DC motor is activated only during the drilling process, while it remains off during other operations. The first servo motor is set to 135° during both the needle slot movement and drilling processes, then changes to 45° for tool changing and suction. It remains at 45° for implanting but operates concurrently with the second servo motor, which is only activated during the implanting process. The second servo motor remains off for all other processes. The evaluation of the needle mechanism is divided into three parts: harvest testing, suction testing, and implant testing. This approach allows for a comprehensive assessment of the mechanism's capabilities. The newly designed needle mechanism is engineered to perform both harvesting and implanting tasks using a single needle. This needle is combined with a punch needle, which is specifically used to cut the arrector pili muscle of the hair follicles. By integrating these functions, the needle mechanism offers a more efficient and streamlined process for hair follicle extraction and implantation. This design aims to enhance the precision and effectiveness of the procedure, making it a significant improvement over previous method [1].

Table 1.

Motor control in Needle mechanism experiment.

| Process | DC Motor | 1st Servo motor | 2nd Servo motor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moving needle slot | OFF | 135° | OFF |

| Drilling | ON | 135° | OFF |

| Tool changing | OFF | 45° | OFF |

| Suction | OFF | 45° | OFF |

| Implanting | OFF | 45° | ON |

3.3.1. Harvesting mechanism

The harvesting (punching) and drilling experiment aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a needle mechanism in performing punching and drilling tasks, specifically in a simulated environment using phantom skin. The results revealed a success rate of 25 out of 30 cases for the punching and drilling functions. The outcomes were determined through careful observation after the punch needle had drilled the wire into the phantom skin. While most wires were successfully embedded within the phantom material, five cases presented different outcomes. Notably, in three instances, the wire adhered to the punch needle instead of being properly embedded. In other cases, the entire wire was embedded within the silicone, while in some, the wire partially protruded from the silicone or even fell off from the phantom skin. The harvesting function achieved a success rate of approximately 83 % from 30 trial cases shown in Fig. 17. (a). Further testing of the needle mechanism showed a 100 % success rate for punching and rotation, with all 30 grafts successfully tested.

Fig. 17.

Implanting process (a) The pie chart displaying the harvesting function result of 30 trial cases with a success rate and failure causes. (b) test results of punch and drill function.

In Fig. 17. (b) summarize the outcomes of an experiment involving wire handling during punching and drilling operations. The left chart indicates that both punching and drilling functions were performed on approximately 30 wires each, with a slightly lower success rate, achieving around 24–25 successful instances. A minimal number of wires fell under "Other Conditions," indicating few failures. The right chart categorizes these failures, showing that wires either fell off the silicone, became embedded in the silicone, or adhered to the needle. Among these, adherence to the needle was the most common issue, occurring three times, while the other two conditions occurred once each. Overall, the experiment demonstrated a high success rate with a few specific issues related to wire adherence and embedding.

Several factors were identified as potential causes of these failures. One key issue was the bending of the wire, which increased the likelihood of the wire hooking onto the needle during the process. Additionally, the depth at which the needle punched into the material played a significant role in these outcomes. If the depth was not correctly calibrated, it could result in the wire either being embedded too deeply, leading to difficulties in retrieval, or not deeply enough, causing it to fall off from the silicone phantom. These findings underscore the importance of precise control over the needle's movement and depth during the punching and drilling processes. The need for further refinement in the mechanism is evident, particularly in addressing the issues related to wire bending and depth control. By optimizing these parameters, the success rate of the needle mechanism could be significantly improved, leading to more reliable and consistent results in practical applications. This experiment provides valuable insights into the challenges and potential solutions in developing a more efficient needle mechanism for medical and industrial applications.

3.3.2. Suction mechanism

An air vacuum pump was used to attempt the extraction of wire from a silicone phantom during the harvest process. The experiment aimed to test the effectiveness of the suction function for this purpose. However, all five trials conducted were unsuccessful, indicating that the air vacuum pump was unable to extract the wire dissected from the silicone phantom. The results suggest that using suction for wire harvesting is not feasible in this context. A likely reason for the failure is the presence of leakages in the needle structure. Despite efforts to seal the design with latex polymer, leakages at the needle tip were inevitable, compromising the effectiveness of the suction mechanism.

3.3.3. Implant mechanism

In this experiment, the process of wire implantation was carried out by first manually inserting the wires into the tip of the implanter. This step was necessary because the suction pump, initially intended for harvesting, proved ineffective and unable to perform the task. Once the wires were securely placed in the implanter, a servo motor was activated to compress a spring mechanism within the device. This action propelled a component inside the implanter, pushing the wires into the silicone phantom, simulating the hair implantation process. The implantation success rate of 53.3 %, achieved in the experiment, highlights both the potential and limitations of the proposed system’s implantation mechanism. While the success rate indicates that the dual-function needle mechanism can perform implantation tasks, several factors contributed to the observed failures in the remaining samples. One key challenge was the manual process of loading wires into the implanter due to the ineffectiveness of the suction system initially intended for this task. This workaround introduced variability in the process, potentially impacting the precision of implantation. The experimental results, detailed in Fig. 18. identified three primary outcomes: successful implantation in 16 out of 30 samples, wire displacement during implantation in 11 samples, and over-implantation (excessive depth) in 3 samples. The primary cause of failures included improper depth control, which led to some wires being implanted either too deeply or insufficiently secured within the silicone phantom. Additionally, the physical properties of the phantom material, including its density and elasticity, may have contributed to the challenges in achieving consistent implantation. It is important to note that the term "high precision" more accurately refers to the system's image-guided follicle localization capability, which achieved an accuracy rate of 89 %. This accuracy reflects the system's ability to precisely identify target positions for both harvesting and implantation. However, the mechanical process of implantation, as measured by the success rate, is acknowledged as an area requiring significant improvement.

Fig. 18.

Implanting process (a) Pie chart displaying implanting function and failure causes in percentage values. (b) test results of testing implant function.

Future work will focus on addressing these limitations by refining the implanter design to incorporate better depth control mechanisms and resolving the suction system's functionality to ensure seamless wire loading and placement. The addition of real-time feedback from the image-guidance system will also enhance control over the implantation depth and improve consistency in the process. While the current success rate of 53.3 % demonstrates the potential of the system, it also emphasizes the need for further refinements to achieve higher reliability and efficiency.

4. Discussion

The robotic system presented in this study demonstrates significant advancements in achieving the precision and adaptability required for hair transplantation. Its ability to attain a movement resolution of ± 1 mm was validated through controlled experiments using a silicone phantom embedded with filaments to simulate hair follicle spacing. These experiments revealed a consistent positional accuracy of ± 0.2 mm, confirming the system's capability to meet the design resolution and ensuring its suitability for accurately targeting individual hair follicles. This precision is essential for addressing the follicle spacing of 1–1.4 mm, reducing the risk of damage to adjacent follicles or tissue and enhancing the system's efficacy in hair transplantation procedures. While these results affirm the system's resolution capabilities, future improvements in motion control algorithms are anticipated to further optimize its reliability under varying operational conditions.

The harvesting and implantation success rates of 83.3 % and 53.3 %, respectively, highlight the system's ability to effectively execute both critical phases of the hair transplantation process. Comparatively, commercially available robotic systems, such as the ARTAS system, report harvesting success rates exceeding 90 % under optimized conditions, but these systems typically rely on manual implantation by surgeons. Research prototypes have demonstrated harvesting rates ranging from 70 % to 85 %, while automated implantation mechanisms often achieve success rates below 50 %. Against these benchmarks, the proposed system performs competitively in follicular harvesting and uniquely integrates an automated implantation function, an innovation absents in many existing systems [52]. This dual-function capability positions the system as a comprehensive solution for robotic hair transplantation.

The system's dual-function needle mechanism, enabling seamless transitions between harvesting and implantation, plays a central role in achieving these results. However, the relatively lower implantation success rate underscores the need for further refinement of the needle mechanism and suction capabilities. Additionally, the integration of a real-time image-guidance system with a follicular localization accuracy of 89 % establishes the system as a robust and precise platform for follicle targeting. These features, combined with its adaptability to diverse head sizes, make the proposed system a promising alternative in the field of robotic hair transplantation.

While the harvesting success rate is slightly lower than that of some established commercial systems, the inclusion of automated implantation and the modular design of the system represent significant innovations. Future iterations of the system aim to incorporate advanced needle mechanisms, machine learning algorithms for enhanced precision, and improvements in suction performance. These developments are expected to elevate the system's performance, making it competitive with or superior to current state-of-the-art systems. The system also incorporates sustainability and ESG principles, enhancing efficiency and reducing waste through modular design and real-time imaging. Its energy-efficient automation minimizes resource usage and waste from repeated procedures, while its accessibility-focused design seeks to lower costs and improve equity in healthcare. Adhering to ethical guidelines, the system prioritizes patient safety, data privacy, and environmental impact. Future iterations will include recyclable materials and further energy-efficient components, aligning with ESG goals and contributing to sustainable innovation in medical robotics. This pilot study establishes the foundation for a robotic system capable of balancing automation, precision, adaptability, and sustainability, paving the way for future developments to meet or exceed the performance of current systems.

5. Conclusion

This research successfully developed and evaluated an integrated image-guided robotic system for hair transplant surgery, demonstrating significant advancements in robotic-assisted follicle harvesting and implantation. The novel surgical robot, which incorporates an image-guided system and a dual-function needle mechanism, effectively addresses the required workspace conditions and showcases high precision, with the image-guided system achieving an accuracy rate of 89 % in detecting hair follicle positions. However, while the dual-function needle mechanism proved effective, achieving harvest and implant success rates of 83.3 % and 53.3 % respectively, there is room for improvement in the needle's design to make it more compact, enhancing the system's overall appearance and user-friendliness. Additionally, the current limitations of the image-guided system, such as the underperformance of the integrated suction system, suggest that further enhancements are needed to improve the system's efficiency. To address these challenges, we propose the integration of a neural network with the image-guided system, which holds promise for overcoming existing limitations and improving the robot's overall functionality. This newly developed system demonstrates great potential and introduces innovative features that can be refined and integrated into future models, contributing to the continued advancement of hair transplant robotic technology. With ongoing improvements, we aim to create even more effective and user-friendly technology for hair transplant surgery in the future.

Funding

This work was supported by the Reinventing University System through Mahidol University under Grant IO 864102063000.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thuangtong Rattapon: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Anantawilailekha Ornpreeya: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Prasertsin Ponchita: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Suthakorn Jackrit: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Kanjana Chaitika and Boontarika Chayutchayodom from Department of Biomedical Engineering, Mahidol University for their help towards the development of this system and BART LAB Researchers for their kind support. The authors would like to thank Dr. Branesh M. Pillai for assisting in manuscript drafting and editing support.

Contributor Information

Rattapon Thuangtong, Email: rattapon.thn@mahidol.ac.th.

Ornpreeya Anantawilailekha, Email: ornpreeya.ana@student.mahidol.edu.

Ponchita Prasertsin, Email: ponchita.pra@student.mahidol.edu.

Jackrit Suthakorn, Email: jackrit.sut@mahidol.ac.th, jackrit@bartlab.org.

References

- 1.Thuangtong R., Suthakorn J. Design, proof-of-concept of single robotic hair transplant mechanisms for both harvest and implant of hair grafts. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;24:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2023.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.York K., Meah N., Bhoyrul B., Sinclair R. A review of the treatment of male pattern hair loss. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21:603–612. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1721463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmina E., Azziz R., Bergfeld W., Escobar-Morreale H.F., Futterweit W., Huddleston H., et al. Female pattern hair loss and androgen excess: a report from the multidisciplinary androgen excess and PCOS committee. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:2875–2891. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam S.M. Hair loss and hair restoration in women. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2020;28(2):205–223. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu D., Huang J., Li K., Chen Y., He Y., Sun Y., et al. Dihydrotestosterone-induced hair regrowth inhibition by activating androgen receptor in C57BL6 mice simulates androgenetic alopecia. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyravian N., Deo S., Daunert S., Jimenez J.J. The inflammatory aspect of male and female pattern hair loss. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:879–881. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S275785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schielein M.C., Tizek L., Ziehfreund S., Sommer R., Biedermann T., Zink A. Stigmatization caused by hair loss–a systematic literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18(12):1357–1368. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Schwarz E. Morgan James Publishing; New York, United States: 2022. The Secret World of Stem Cell Therapy: What YOU Need to Know about the Health, Beauty, and Anti-Aging Breakthrough. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose P.T. Hair restoration surgery: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;15:361–370. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S53980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imagawa K. InHair Restoration Surgery in Asians. Springer Japan; Tokyo: 2010. Back to the future: a brief but significant history of hair transplantation in Asians; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhamzawi N.K. Keloid scars arising after follicular unit extraction hair transplantation. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg. 2020;13(3):237. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_181_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins K., Avram M.R. Hair transplantation and follicular unit extraction. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(3):463–478. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez F., Alam M., Vogel J.E., Avram M. Hair transplantation: basic overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jimenez F., Vogel J.E., Avram M. CME article Part II. Hair transplantation: surgical technique. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg A.K., Garg S. Complications of hair transplant procedures—causes and management. Indian J Plast Surg. 2021;54(04):477–482. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein G.K., Epstein J., Nikolic J. Follicular unit excision: current practice and future developments. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2020;28(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A.K., Love R.P., True R.H., Harris J.A. Follicular unit excision punches and devices. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1705–1711. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avram M.R., Watkins S. Robotic hair transplantation. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2020;28(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treatments for Hair Loss – ISHRS, [Online]. Available: 〈https://ishrs.org/patients/treatments-for-hair-loss/〉.

- 20.Jimenez F., Alam M., Vogel J.E., Avram M. Hair transplantation: basic overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez F., Vogel J.E., Avram M. CME article Part II. Hair transplantation: surgical technique. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg A.K., Garg S. Complications of hair transplant procedures—causes and management. Indian J Plast Surg. 2021;54(04):477–482. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhamzawi N.K. Keloid scars arising after follicular unit extraction hair transplantation. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg. 2020;13(3):237. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_181_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashid R.M. Follicular unit extraction with the Artas robotic hair transplant system system: an evaluation of FUE yield. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(4):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avram M.R., Watkins S. Robotic hair transplantation. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2020;28(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alhamzawi N.K. Keloid scars arising after follicular unit extraction hair transplantation. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg. 2020;13(3):237. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_181_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins K., Avram M.R. Hair transplantation and follicular unit extraction. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(3):463–478. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein G.K., Epstein J., Nikolic J. Follicular unit excision: current practice and future developments. Facial Plast Surg Clin. 2020;28(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta A.K., Ivanova I.A., Renaud H.J. How good is artificial intelligence (AI) at solving hairy problems? A review of AI applications in hair restoration and hair disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2) doi: 10.1111/dth.14811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song X., Guo S., Han L., Wang L., Yang W., Wang G., et al. Research on hair removal algorithm of dermatoscopic images based on maximum variance fuzzy clustering and optimization Criminisi algorithm. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;78 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erdoǧan K., Acun O., Küçükmanísa A., Duvar R., Bayramoǧlu A., Urhan O. KEBOT: an artificial intelligence based comprehensive analysis system for FUE based hair transplantation. IEEE Access. 2020;8:200461–200476. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta A.K., Ivanova I.A., Renaud H.J. How good is artificial intelligence (AI) at solving hairy problems? A review of AI applications in hair restoration and hair disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2) doi: 10.1111/dth.14811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim M., Kang S., Lee B.D. Evaluation of automated measurement of hair density using deep neural networks. Sensors. 2022;22(2):650. doi: 10.3390/s22020650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta A.K., Love R.P., True R.H., Harris J.A. Follicular unit excision punches and devices. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1705–1711. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rashid R.M., Bicknell L.T. Follicular unit extraction hair transplant automation: options in overcoming challenges of the latest technology in hair restoration with the goal of avoiding the line scar. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18(9):12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thai M.T., Phan P.T., Hoang T.T., Wong S., Lovell N.H., Do T.N. Advanced intelligent systems for surgical robotics. Adv Intell Syst. 2020;2(8) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knoedler L., Ruppel F., Kauke-Navarro M., Obed D., Wu M., Prantl L., et al. Hair transplantation in the United States: a population-based survey of female and male pattern baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg–Glob Open. 2023 Nov 14;11(11) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000005386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kayiran O., Cihandide E. Evolution of hair transplantation. Plastic and aesthetic research. 2018 Rose PT. Advances in hair restoration. Dermatol Clin. 2018 Jan 1;36(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiyandini J.R. A framework to determine the potential for success of new medical robotic products: assessment by cooper scoring model and TOPSIS analysis. Master's Thesis, Univ Twente. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhami L. Psychology of hair loss patients and importance of counseling. Indian J Plast Surg. 2021;54(04):411–415. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1741037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajabboevna A.R., Yangiboyevna N.S., Farmanovna I.E., Baxodirovna S.D. The importance of complex treatment in hair loss. Web Sci Int Sci Res J. 2022;3(5):1814–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagy T.D., Haidegger T. Performance and capability assessment in surgical subtask automation. Sensors. 2022;22(7):2501. doi: 10.3390/s22072501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haidegger T. Autonomy for surgical robots: concepts and paradigms. IEEE Trans Med Robot Bionics. 2019;1(2):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ball R., Shu C., Xi P., Rioux M., Luximon Y., Molenbroek J. A comparison between Chinese and Caucasian head shapes. Appl Ergon. 2010;41(6):832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jimenez F., Ruifernández J.M. Distribution of human hair in follicular units: a mathematical model for estimating the donor size in follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(4):294–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J., Li R., Li J., Wang J., Wu Q., Liu X. Dual-view 3D object recognition and detection via Lidar point cloud and camera image. Robot Auton Syst. 2022;150 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burger W., Burge M. Digital Image Processing: An Algorithmic Introduction. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2022. Scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) pp. 709–763. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agrawal P., Sharma T., Verma N.K. Supervised approach for object identification using speeded up robust features. Int J Adv Intell Paradig. 2020;15(2):165–182. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y., Liu F., Qu Q., Fan Z.X., Miao Y., Hu Z.Q. Evaluating the satisfaction of patients undergoing hair transplantation surgery using the FACE-Q scales. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:376–382. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bae T.W., Jung Y.C., Kim K.H. Needle transportable semi-automatic hair follicle implanter and image-based hair density estimation for advanced hair transplantation surgery. Appl Sci. 2020;10(11):4046. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karakaya S., Kucukyildiz G., Ocak H. A new mobile robot toolbox for MATLAB. J Intell Robot Syst. 2017;87:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Real-World Evaluation Study Confirms Benefits of ARTAS iX Robotic Hair Restoration System. Practical Dermatology. Available from: 〈https://practicaldermatology.com/news/real-world-evaluation-study-confirms-benefits-of-artas-ix-robotic-hair-restoration-system/2457560/?〉.