Abstract

The oxidation of para- and ortho-substituted anilines with iridium (IV) in aqueous perchloric acid has been investigated. The kinetic study reveals a first-order dependence with respect to both the oxidant and the substrates. The reaction rate increases with the presence of electron-donating groups and decreases with electron-withdrawing groups, which is explained by the linear free energy relationship (LFER) theory according to Hammett’s equation. The Hammett reaction constant (ρ) is found to be negative (ρ < 0), and it increases with temperature. Various thermodynamic parameters have been evaluated, and the validity of the isokinetic relationship has been discussed. The isokinetic temperature (β), calculated from the Van’t Hoff plot (317 K), Compensation plot (317.4 K), and Arrhenius plot (317 K), is consistent. However, the isokinetic temperature obtained from the Exner plot (439.32 K) exceeds the experimental temperature range (303–323 K), indicating that enthalpy factors likely play a more significant role in controlling the reaction. Based on the kinetic results, a probable reaction mechanism is proposed.

Keywords: Anilines, Hexachloroiridate (IV), Reaction kinetics, Structural reactivity relationship, Substituent Effect, Thermal analysis

Subject terms: Chemistry, Energy science and technology

Introduction

Substituted anilines are widely used in various industries, including pesticide production, dye manufacturing, and pharmaceuticals1,2. However, the extensive use of aromatic anilines has led to their increased concentration in aquatic environments3,4. Many substituted anilines are classified as restricted contaminants by the European Union, as their release poses significant environmental concerns. Previous studies have focused on treating anilines using various effective oxidants, such as ClO25, Fenton’s reagent6, H2O27, MnO28, Fe (VI)9, MnO4-10, TiO211, and IO4-12,13. These pollutants often enter the environment through the use of pesticides, fungicides, and dyes in both industrial and agricultural processes, leaving behind chemical residues14. Additionally, substituted aniline residues may act as intermediates or precursors to pesticides and halogenated disinfection by-products15,16. Given that some anilines are carcinogenic, toxic, and can induce adverse physiological effects, it is of paramount importance to develop effective transformation methods to eliminate these contaminants from the environment, particularly from aquatic systems.

Iridium (IV) is widely used both as a catalyst and as an oxidant in electron transfer processes. It undergoes reduction to iridium (III) through a one-electron transfer, and this reduced form is also employed as a catalyst17,18. The oxidation kinetics of Ir (IV) have been studied in various reactions, where it functions both as a catalyst and an oxidant19–21. Iridium (IV) chloride is often preferred as an oxidant due to its ease of handling and its behavior in outer-sphere one-electron transfer reactions22–24. This oxidant has also been used in reactions involving trace metal-ion catalysis, although its activity can be inhibited by chelating agents. For example, the oxidation of thioglycolic acid in the presence of bathophenanthroline disulfonate, a chelating agent, has been studied. A review of the literature reveals that no kinetic studies have been conducted on the interaction between anilines and [IrCl6]2-. This work presents the results of a series of experiments investigating the electron transfer pathway from anilines to hexachloroiridate (IV) in an acidic medium, using spectrophotometric techniques.

The study of substituent effects and thermodynamic parameters is a key focus for evaluating the reaction mechanism between substituted anilines and oxidants in both aqueous and non-aqueous media25–28. A non-linear Hammett plot has been observed in these correlations29. The Hammett equation, along with linear free energy relationships (LFER) and isokinetic/enthalpy-entropy relationships, has been widely used to correlate the rate constants and equilibrium constants of reactions30–32. In recent years, there has been significant research exploring the enthalpy-entropy compensation effect and the isokinetic relationship33–37.

Many researchers have suggested that the enthalpy-entropy compensation effect, observed by plotting ∆H# against ∆S#, may arise from random experimental errors38. However, the existence of both kinetic and thermodynamic compensation has been rigorously studied39–41. In light of this, the present study focuses on the kinetics of fourteen substituted anilines reacting with [IrCl6]2- in an aqueous acidic medium. A detailed and plausible mechanistic scheme is proposed. Additionally, thermodynamic parameters are evaluated, and a linear free energy relationship (LFER) is constructed to describe the influence of substituents on the reactivity pattern, providing insight into the reaction mechanism.

Experimental

Materials

The substituted anilines used in this study included H, p-SO3H, p-COOH, O-COOH, p-NO2, p-Br, p-Cl, p-OCH3, p-I, p-COOEt, p-COMe, p-F, p-CH3, and 2,6-dimethyl. All reagents were of AnalaR grade (99%) (Table 1). The oxidant solution (Iridium (IV) chloride hydrate, Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by dissolving the required amount in deionized water. This solution is stable under normal conditions and its stability is further enhanced when stored in dark-coated bottles at refrigerated temperatures (~ 5 °C). Conductivity water, distilled from an alkaline permanganate solution, was used for the reaction experiments.

Table 1. Systematic chemical name, preferred IUPAC name and initial purity of substituted anilines

| Anilines | IUPAC name | Systematic IUPAC name | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H (Phenylamine) | Aniline | Benzenamine | ≥ 99.5 |

| p-SO3H (Sulfanilic acid) | 4-aminobenzene-1-sulfonic acid | – | ≥ 99.0 |

| p-COOH (p-Aminobenzoic acid) | 4-Aminobenzoic acid | – | ≥ 99.0 |

| O-COOH (Anthranilic acid) | 2-Aminobenzoic acid | 2-Aminobenzenecarboxylic acid | ≥ 99.0 |

| p-NO2 (p-Nitroaniline) | 4-Nitroaniline | 4-Nitrobenzenamine | ≥ 98.0 |

| p-Br (p-Bromoaniline) | 4-Bromoaniline | 4-Bromobenzenamine | ≥ 98.0 |

| p-Cl (p-Chloroaniline) | 4-Chloroaniline | 4-Chlorobenzenamine | ≥ 99.0 |

| p-OCH3 (p-Anisidine/4-Aminoanisole) | 4-Methoxyaniline | – | ≥ 99.0 |

| p-I (p-Iodoaniline) | 4-Iodoaniline | 4-Iodobenzenamine | ≥ 98.0 |

| p-COOC2H5 (Benzocaine) | Ethyl 4-aminobenzoate | – | ≥ 99.0 |

| p-COCH3 (p-Aminoacetophenone) | 1-(4-Aminophenyl)ethanone | – | ≥ 98.0 |

| p-F (p-Floroaniline) | 4-Floroaniline | 4-Florobenzenamine | ≥ 98.0 |

| p-CH3 (p-Toluidine) | 4-Methylaniline | 4-Mrthylbenzenamine | ≥ 99.0 |

| 2,6-(CH3)2 (2,6-Xylidine) | 2,6-Dimethylaniline | 2,6-dimethylbenzenamine | ≥ 99.0 |

Spectrophotometric measurements

Absorption measurements were performed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (PharmaSpec 1800, SHIMADZU) with 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes, controlled by UV-Probe software and digital thermostat to regulate the temperature. The reactions were monitored spectrophotometrically at intervals from 120 to 1800 s at λmax = 485 nm (ε = 4050 dm³ mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹). To study the kinetics, the reaction mixtures were placed in black-painted glass stoppered Erlenmeyer flasks, which were suspended in a thermostated water bath. The reactions were initiated by adding a thermally pre-equilibrated solution of Iridium (IV). The reaction kinetics were tracked spectrophotometrically by periodically measuring the absorbance of the remaining Iridium (IV) at 485 nm, over the temperature range of 303–323 K, until up to 90% of the reaction was complete.

Statistical data analysis

The pseudo-first order rate constants were calculated from absorbance time data using the StatGraphics Centurion Software (19 × 64). Correlation analysis was performed using Microsoft excel (LINEST). The fitting validity was discussed by the use of standard deviation (SD) and correlation coefficient (linear regression (R2)42–44.

Stoichiometry and product analysis

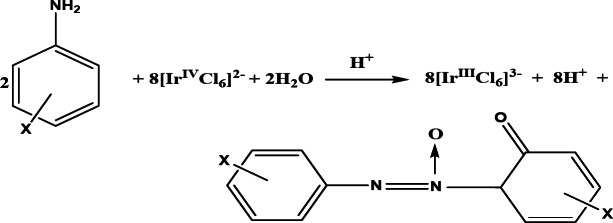

The reaction stoichiometry was established by adding sufficiently considerable amount of oxidant over that of anilines. The excess concentration of oxidant was computed after consumption the reactants by UV-visible spectrophotometer at λmax, 485 nm (ε, 4050 dm3 mol− 1 cm− 1). The results represented by following equation. The oxidation product of aniline was further been identified by spectrally to be corresponding 2-keto-azoxybenzene.

Results and discussion

The concentration of Ir(IV) (0.2-1.0)×10− 4 mol dm-3 was varied fixed concentrations of substrates (0.2 mol dm-3) and also keeping constant concentrations of hydrogen ion to be 0.1 mol dm-3 at 318 K. The pseudo-first order rate constants (k’, s-1) were found to be independent of gross initial concentrations of Ir(IV), confirming first order dependence with respect to the oxidant.

Pseudo-first order rate constants were evaluated at increasing concentrations of substrate (0.5–30.0) ×10− 2 mol dm-3) and a plot of these rate constants versus the concentration yielded a straight line passing through the origin confirming first order with respect to substrate.

The effect of hydrogen ion concentration was studied by employing perchloric acid. The concentration of hydrogen ion was varied from 0.1 to 0.5 mol dm-3 at fixed concentrations of other. The rate decreases with increasing hydrogen ion concentration. The effect of ionic strength was studied using lithium perchlorate and the rate increases with increasing ionic strength.

The reaction of substituted anilines (H, p-SO3H, p-COOH, O-COOH, p-NO2, p-Br, p-Cl, p-OCH3, p-I, p-COOEt, p-COMe, p-F, p-CH3, 2, 6-dimethyl) was studied spectrophotometrically at (303–323) K in the presence of varying excess of anilines (0.2 mol dm-3) over the oxidant (1.0 × 10− 4 mol dm-3) to establish pseudo-first-order kinetics. The second order rate constants, k2, were evaluated and details are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Second-order rate constants for the oxidation of substituted anilines by [IrCl6]2- in aqueous acidic medium.

| Substrate | k2 (dm3 mol− 1 s− 1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 303 K | 308 K | 313 K | 318 K | 323 K | |

| H, (107 k2) | 1.99 | 2.48 | 3.68 | 6.17 | 8.76 |

| p-OMe, 107 k2 | 5.76 | 7.45 | 8.41 | 9.62 | 11.5 |

| p-Me, 107 k2 | 3.35 | 3.80 | 4.56 | 5.43 | 6.66 |

| 2,6 diMe, 107 k2 | 3.45 | 4.09 | 4.35 | 5.06 | 5.59 |

| p-F, 107 k2 | 2.45 | 2.92 | 3.33 | 3.71 | 4.20 |

| p-Cl, 107 k2 | 1.52 | 2.16 | 2.95 | 3.68 | 4.37 |

| p-Br, 108 k2 | 4.19 | 6.91 | 14.1 | 22.2 | 29.8 |

| p-I, 108 k2 | 5.25 | 6.68 | 11.1 | 14.3 | 16.9 |

| p-COMe, 108 k2 | 3.04 | 3.68 | 5.30 | 8.24 | 14.9 |

| p-COOEt, 108 k2 | 1.52 | 2.07 | 3.22 | 4.84 | 8.48 |

| p-COOH, 108 k2 | 0.74 | 1.29 | 1.75 | 2.12 | 3.32 |

| p-SO3H, 109 k2 | 5.07 | 7.37 | 9.21 | 11.5 | 15.2 |

| O-COOH, 109 k2 | 3.22 | 4.15 | 5.53 | 7.37 | 9.21 |

| p-NO2, 109 k2 | 3.65 | 4.43 | 5.30 | 7.29 | 9.47 |

Mechanism of oxidation

Substitution of [IrCl6]2- complex is inactive to react and inner sphere kinetics does not occur in such reactions. In all prospect, an outer-sphere complex is built which further produced the oxidation products through decomposition. Since [IrCl6]3- and Cl- don’t affect the rate of reaction by which eliminate the all probability of rate controlling step involving [IrCl6]3- and complex formation between substrate and oxidant by dissociation of [IrCl6]2-. Rate is inhibited by increase concentration of hydrogen ion, thus considering first-order respecting to reactants and inhibiting effect of acid, the following mechanism can be proposed regarding experimental outcomes.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Applying steady state treatment to the intermediate, such a mechanism leads to rate law (4)

| 4 |

Ion-pairing of oxidant and substrate was structured in the fast step, i.e. a slow electron transfer process is occurred through an outer sphere mechanism within the complex45–47. Hexachloroiridate (IV) is a stable reagent for substitution reactions or hydrolysis over a broad range of acidity. Even though, a fresh solution of the oxidant was used in whole study, since the possibility of [IrCl6 (OH)]3- to be the reactive form is implausible under the experimental conditions. The following scheme accounts for the reaction events precisely.

Scheme 1. Reaction scheme proposed for the oxidation of anilines by [IrCl6]2−

Thermodynamic parameters and the isokinetic relationship

Investigating the effect of temperature on the reaction rate is crucial for understanding the thermodynamic parameters and, ultimately, the nature of the reaction mechanism in solution. In this context, Exner’s equation and the isokinetic relationship are valuable tools for determining whether a similar mechanism governs a series of reactions48. Additionally, the isokinetic parameter β is particularly useful for assessing whether the system is controlled by entropy or enthalpy.

In view of these observations, the activation parameters were evaluated from k2 at (303–323) K by employing Arrhenius and Eyring Eqs. (5) and (6) through Van’t Hoff plot by method of least squares (Table 2).

| 5 |

where ‘k’ is a second order rate constant (dm3 mol− 1 s− 1) and other terms have their usual meaning. ΔH#, ΔS# and ΔG# were evaluated from Eq. (6) to (8)

| 6 |

| 7 |

and

| 8 |

and are collected in following Table 3.

Table 3.

Activation parameters in the reaction between anilines and [IrCl6]2−.

| Anilines | ∆H#, kJ/mol | ∆S#, J/K mol | ∆Ea#, kJ/mol | ∆G#, kJ/mol | lnA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | 40.46 ± 0.044 | − 269.91 ± 0.861 | 43.06 | 124.94 | 11.16 |

| p-SO3H | 54.59 ± 0.103 | − 219.81 ± 2.048 | 57.19 | 123.39 | 17.24 |

| p-COOH | 36.54 ± 0.055 | − 286.28 ± 1.109 | 39.15 | 126.15 | 9.11 |

| O-COOH | 47.89 ± 0.096 | − 226.25 ± 1.904 | 50.50 | 118.71 | 16.51 |

| p-NO2 | 40.93 ± 0.019 | − 272.52 ± 0.369 | 43.53 | 126.23 | 10.84 |

| p-Br | 25.52 ± 0.029 | − 284.94 ± 0.581 | 28.12 | 114.71 | 9.33 |

| p-Cl | 40.44 ± 0.06 | − 241.58 ± 1.19 | 43.04 | 116.05 | 14.62 |

| p-OCH3 | 60.33 ± 0.096 | − 174.94 ± 1.9 | 62.93 | 115.09 | 22.49 |

| p-I | 23.98 ± 0.038 | − 284.98 ± 0.748 | 26.58 | 113.18 | 9.35 |

| p-COOC2H5 | 66.98 ± 0.089 | − 174.26 ± 1.778 | 69.58 | 121.52 | 22.61 |

| p-COCH3 | 61.95 ± 0.149 | − 185.59 ± 2.948 | 64.54 | 120.04 | 21.17 |

| p-F | 16.52 ± 0.026 | − 314.04 ± 0.519 | 19.12 | 114.81 | 5.82 |

| p-CH3 | 80.41 ± 0.116 | − 120.58 ± 2.29 | 83.01 | 118.14 | 29.24 |

| 2,6 diMe | 18.85 ± 0.019 | − 309.15 ± 0.372 | 21.45 | 115.61 | 6.45 |

The large (-)ve entropy of activation is arising owing to solvation effects being predominant in such reactions. Since these substituted anilines exhibit different polarities, the extent of solvation is, therefore, indicating variations in entropy of activation. A small difference in the reaction rates for various anilines may be noted for a change in the basic strength of these anilines bringing change in the availability of the nitrogen lone-pair in amino groups.

The validity of isokinetic relationship ΔH# = βΔS# where β is isokinetic temperature was determined by constructing a plot between ΔH# and ΔS# (Fig. 1, R2 = 0.94, SD = 4.74) exhibiting a linear relationship and confirming validity of isokinetic relationship for these anilines apart from a common mechanism for such reactions. The isokinetic temperature β obtained from the figure is 317.7 K and free energy is 120.32 kJ/mol.

Fig. 1.

A Plot between ΔS# and ΔH# (Van’t hoff plot). [Substrate] = 2.0 × 10− 2 mol/L; [IrCl6]2- = 2.0 × 10− 4 mol/L; [I] = 1.0 mol/L.

If Leffler’s view49 are taken into account, the reaction is neither isoentropic nor isoenthalpic but the almost constancy in the values of ΔG# as mentioned in the Table 3. Such a situation normally corresponds to the fact that these anilines proceed by a common mechanism despite slight differences in their structures complies with the compensation law also known as the isokinetic relationship.

Further Exner50 suggested a method for calculation of isokinetic temperature by employing relationships (9) and (10).

| 10 |

| 11 |

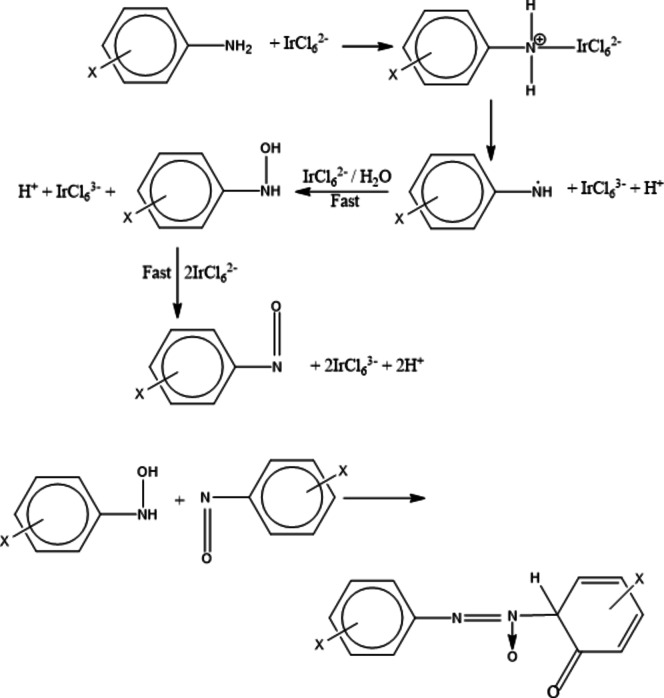

where ‘a’ and ‘b’ are constants. k2 is second order rate constants at two different temperatures T1 and T2 respectively for a series of substituted anilines.

A plot of ln k2 (at 308 K) versus ln k2 (at 318 K) was made that yielded a straight line (Fig. 2, R2 = 0.979, SD = 0.285) accounting for validity of Exner’s plot indicates that a common mechanism is operating in examination of all substituted anilines. The isokinetic effect is unlike that the compensation effect and β was then calculated from Eq. (10) employ ‘b’ from the gradient of the plot to be 439.32 K. This value of β is well above the experimental temperature range ascribing the reactions to be enthalpy controlled51.

Fig. 2.

A Plot between ln k2 (35 °C) and ln k2 (45 °C) (Exner’s plot). [Substrate] = 2.0 × 10− 2 mol/L; [IrCl6]2- = 2.0 × 10− 4 mol/L; [I] = 1.0 mol/L.

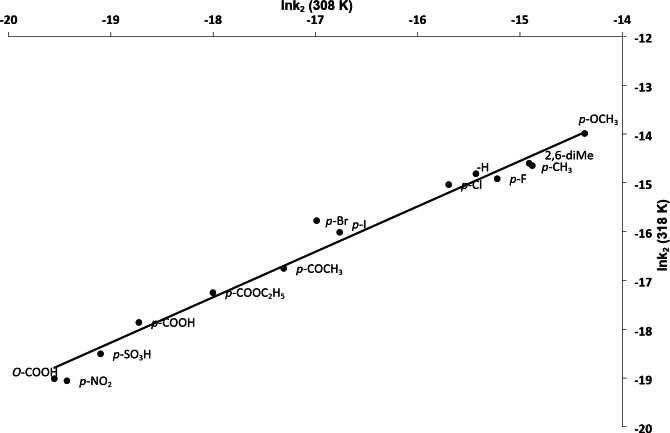

The facts that all the substituted anilines investigated indicate identical kinetic behavior. The activation free energies (∆G#) do not differ significantly and also the activation energy (∆E#) correlates with the ln A (frequency factor) (Fig. 3, R2 = 0.993, SD = 1.75) and so the activation enthalpy (∆H#) with activation entropy (∆S#), further propound the operational of a common mechanism in these oxidation reactions. The slope of compensation plot is 317.4, which is again within the experimental temperature range.

Fig. 3.

A compensation Plot between Ea and ln A. [Substrate] = 2.0 × 10− 2 mol/L; [IrCl6]2− = 2.0 × 10− 4 mol/L; [I] = 1.0 mol/L.

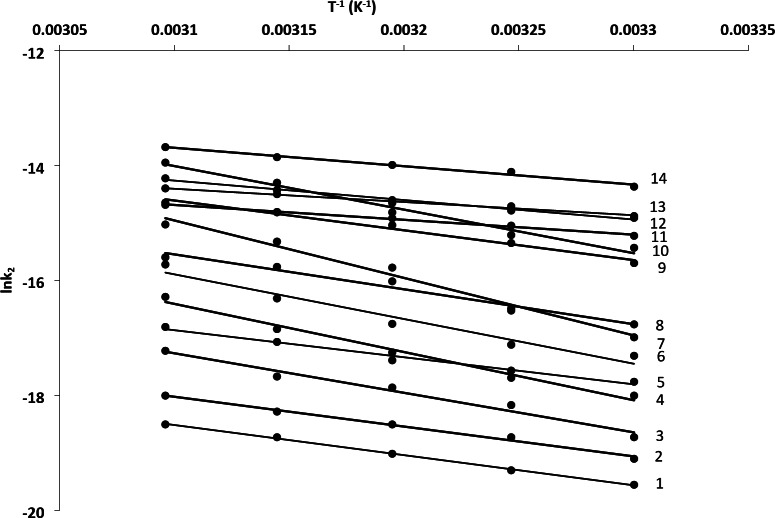

The validity of the isokinetic relationship can be confirmed by the common intersection point of the Arrhenius lines (Fig. 4), which verifies the isokinetic relationship. The isokinetic temperature, determined to be 317 K, closely matches the temperature obtained from both the Van’t Hoff and Compensation plots. All reactions studied were governed by enthalpy52. Kinetic compensation was observed only when the logarithm of the frequency factor (ln A) showed a linear dependence on the activation energy (∆E#). Thermodynamic compensation can be closely derived from the Van’t Hoff equation for equilibrium states, where changes in enthalpy are closely related to changes in entropy.

Fig. 4.

Arrhenius plots of substituted anilines. [Substrate] = 2.0 × 10− 2 mol/L; [IrCl6]2- = 2.0 × 10− 4 mol/L; [I] = 1.0 mol/L. (1) p-NO2, (2) –H, (3) p-SO3H, (4) p-COOC2H5, (5) p-COOH, (6) p-COCH3, (7) p-CH3, (8) O-COOH, (9) p-Cl, (10) p-OCH3, (11) 2,6-diMe, (12) p-Br, (13) p-F, (14) p-I.

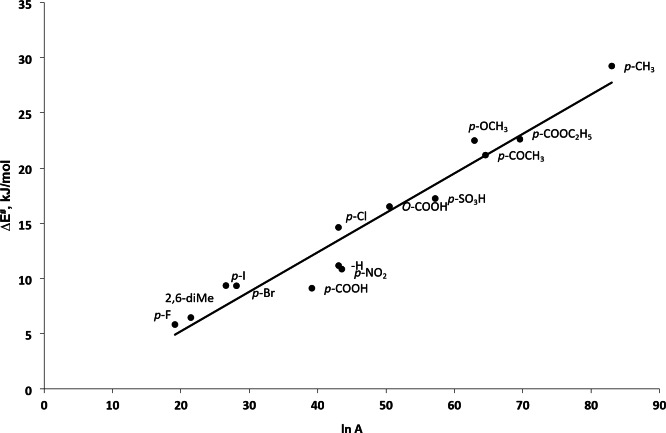

Structure-reactivity correlation

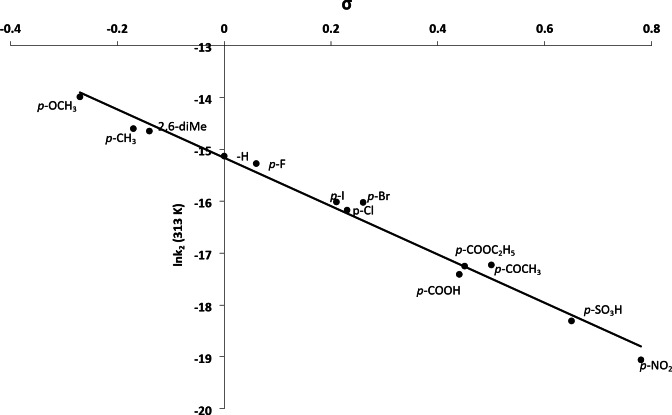

The present reaction has been studied at five different temperatures (303–323) K in aqueous acidic medium involving aniline and 13 substituted anilines. The second-order rate constants were evaluated (Table 2). The investigation of these data shows that the oxidation of anilines is enhanced by electron donating groups as substituents and inhibited by electron removing groups in the benzene ring. The reactivity order is as follows: p-OCH3 > p-CH3 > p-H > 2,6-dimethyl > p-F > p-Cl > p-Br > p-I > p-COCH3 > p-COOC2H5 > p-COOH > p-SO3H > O-COOH > p-NO2 for the substituents. A linear relationship is obtained by plotting Hammett equation between σ (substituent constants) and lnk2 for different substituents (Fig. 5, R2 = 0.984, SD = 0.476) at 313 K with ρ = ˗ 4.66.

Fig. 5.

Hammett plot of ln k2 vs. substituent constant, σ at 313 K. [Substrate] = 2.0 × 10− 2 mol/L; [IrCl6]2- = 2.0 × 10− 4 mol/L; [I] = 1.0 mol/L.

The value of reaction constant (ρ) is derived by the slope of Hammett plot. Values of reaction constants at different temperatures are shown in Table 4. As remarked by Hammett53, the reaction with positive ρ values is enhanced by electron withdrawing substituents on benzene ring, while in the contrary with negative ρ values; reaction is inhibited by electron withdrawing from benzene ring. In present study, the rate of oxidation reactions was decreased by the electron withdrawal effect from benzene ring and increased by electron donating effect. These outcomes affirm the negative values of reaction constants (ρ) obtained from the Hammett plot. Negative ρ values endorse a formation of positive charge at the nitrogen atom of the aniline moiety in transition state.

Table 4.

Values of reaction constants at different temperature.

| Temperature (K) | Reaction constant, ρ | Correlation coefficient | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 303 | − 5.0956 | 0.913 | 0.754 |

| 308 | − 4.95 | 0.922 | 0.737 |

| 313 | − 4.791 | 0.904 | 0.772 |

| 318 | − 4.6472 | 0.876 | 0.817 |

| 323 | − 4.387 | 0.847 | 0.863 |

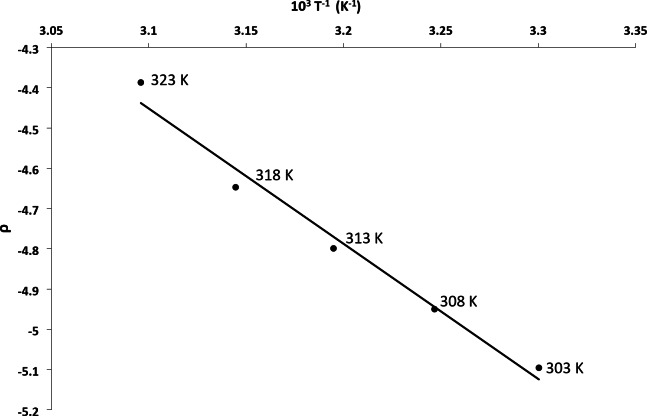

If the slope of the Exner plot is less than unity, that means that the selectivity of the reagents diminishes with increasing temperature, however, in these oxidation series, slope is less than unity but tended towards to unity (0.9585). If slope is greater than unity than the selectivity of the reagents increases. The comparison of reaction constant (ρ) at different temperatures indicates that the negative value of reaction constant (ρ) decreases with increasing the temperature and ρ varies linearly with (1/T) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A plot between hammett reaction constant and (T)−1.

This is expected that at high temperature, the selectivity of the reagent becomes less due to thermal randomization and therefore the sensitivity of the reaction towards the electron density changes decreases at the reaction site.

Conclusion

In this study, author has reported the detailed mechanism of oxidation of substituted anilines by [IrCl6]2-. (a) The linear relationship between the contributions of entropy and enthalpy implicit that the susceptibility of the thermal reaction of anilines to substituent effect would be inversed simply by alter the temperature (compensation effect). (b) At isokinetic temperature, structural changes do not alter the rate constants of a reaction series as the changes of ∆H are counterbalanced by changes of ∆S, so the presence of an isokinetic relationship suggests a common structure of the transition state of all oxidation reactions. (c) The isokinetic temperature is above the experimental temperature range shows that the reactions were enthalpy controlled. (d) The high negative values of entropy indicating the more ordered complex formation in a rate determining step. (e) The negative ρ values computed from the Hammett plot divulge that a positively charged reactive intermediate formation during the oxidation, indicating diminution of nitrogen lone pair and it can be facilitate when the oxidant builds a complex with substrate in which lone pair is involved in coordination with electron deficient centre of a metal ion.

Acknowledgements

Author acknowledges the financial support of start-up grant (BSR) provided by the University Grant Commission, New Delhi, India. Author is also thankful to the Material Research Centre, Malviya National Institute of Technology, Jaipur (MNIT-Jaipur) where the spectral analysis has been carried out. This work is dedicated to (late) Prof. P. D. Sharma, Ex-Head of Department of Chemistry, UOR, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. I confirm that the potential reviewers I recommend are experts in the subject matter, have no conflicts of interest with the author, and are not affiliated with the same institute.

Author contributions

R. S.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Experimental Investigation, Calculations, Writing, Review and Editing.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liang, J. et al. Degradation of aromatic amines in textile-dyeing sludge by combining the ultrasound technique technique with potassium permanganate treatment. J. Hazard. Mater.314, 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tekle-Rottering, A. et al. Ozonation of anilines: kinetics, stoichiometry, product identification and elucidation of pathways. Water Res.98, 147–159 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onuska, F. I., Terry, K. A. & Maguire, J. R. Analysis of aromatic amines in industrial waste water by capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Water Qual. Res. J. Can.35, 245–261 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muz, M. et al. Nontargeted detection and identification of (aromatic) amines in environmental samples based on diagnostic derivatization and LC-high resolution mass spectrometry. Chemosphere166, 300–310 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilar, C. A. H., Narayanan, J., Singh, N. & Thangarasu, P. Kinetics and mechanism for the oxidation of anilines by ClO2: a combined experimental and computational study. J. Phys. Org. Chem.27, 440–449 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casero, I., Sicilia, D., Rubio, S. & Perez Bendito, D. Chemical degradation of aromatic amines by fentons reagent. Water Res.31, 1985–1995 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaue, S., Tsubakino, T., Nishiyama, Y. & Ishii, Y. Oxidation of aromatic-amines with hydrogen-peroxide catalyzed by cetylpyridinium heteropolyoxometalates. J. Org. Chem.58, 3633–3638 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salter-Blanc, A. J., Bylaska, E. J., Lyon, M. A., Ness, S. C. & Tratnyek, P. G. Structure-activity relationships for rates of aromatic amine oxidation by manganese dioxide. Environ. Sci. Technol.50, 5094–5102 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun, S. et al. Transformation of substituted anilines by ferrate (VI): kinetics, pathways, and effect of dissolved organic matter. Chem. Eng. J.332, 245–252 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang, S. Y., Duan, J. B., Zhou, Y., Gao, Y. & Jiang, J. Oxidation kinetics of anilines by aqueous permanganate and effects of manganese products: comparison to phenols. Chemosphere235, 104–112 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitoi, I., Oancea, P., Cristea, I., Constsntin, L. & Nechifor, G. Kinetics and mechanism of chlorinated aniline degradation Bt TiO2 photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem.298, 17–23 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaushik, R. D., Singh, J., Manila, Tyagi, P. & Singh, P. Uncatalysed non-malapradian periodate oxidation of aromatic amines- An overview. J. Indian Chem. Soc.91, 1483–1490 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaushik, R. D., Arya, R. K. & Kumar, S. Kinetics and mechanism of periodate oxidation of 0-anisidine in acetone-water medium. J. Indian Chem. Soc.87, 317–323 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliviero, L., Barbier, J. & Duprez, D. Wet air oxidation of nitrogen-containing organic compounds and ammonia in aqueous media. Appl. Catal. B Environ.40, 163–184 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, J., Zhang, X., Zhu, X. & Lu, Y. Removal of intermediate aromatic halogenated DBPs by activated carbon adsorption: a new approach to controlling halogenated DBPs in chlorinated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol.51, 3435–3444 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han, J. & Zhang, X. Evaluating the comparative toxicity of DBP mixtures from different disinfection csenarios: a new approach by combining freeze-drying or rotoevaporation with a marine polychaete bioassay. Environ. Sci. Technol.52, 10552–10561 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajput, S. K., Sharma, A. & Bapat, K.N. A study of substituent effect on the oxidative strength of hexacyanoferrate (III): kinetics and mechanism of ir (III) catalyzed oxidation of lactose in acidic medium. Acta Cienc. Ind.34, 115–120 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh, S. P., Singh, A. K. & Singh, A. K. Kinetics of ir (III)-catalyzed oxidation of D-glucose by potassium iodate in aqueous alkaline medium. J. Carbohydr. Chem.28, 278–292 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sailani, R. Spectrophotometric kinetic and mechanistic investigation of chlorpromazine radical cation with hexachloroiridate (IV) in catalyzed aqueous acid medium. ChemistrySelect6, 8472–8479 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sailani, R., Pareek, D., Meena, A., Jangid, K. & Khandelwal, C. L. Kinetics and mechanism of electron transfer reactions: oxidation of sulfanilic acid by hexachloroiridate (IV) in acid medium. Indian J. Chem.55, 1074–1079 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong, J. et al. Elding, L. I. Kinetics and mechanism of oxidation of the anti-tubercular prodrug isoniazid and its analog by iridium(IV) as models for biological redox systems. Dalton Trans.46, 8377–8386 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doona, C. J. & Stanbury, D. M. Equilibrium and redox kinetics of copper (II) – Thiourea complexes. Inorg. Chem.35, 3210–3216 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doona, C. J. & Stanbury, D. M. Adventitious catalysis in oscillatory reductions by thiourea. J. Phys. Chem.98, 12630–12634 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanbury, D. M. & Lednicky, L. A. Outer-sphere electron-transfer reactions involving the chlorite/chlorine dioxide couple. Activation barriers for bent triatomic species. J. Am. Chem. Soc.106, 2847–2853 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhuvaneshwari, D. S. & Elango, K. P. Studies on the kinetics of imidazolium flurochromate oxidation of some meta- and para-substituted anilines in nonaqueous media. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 38, 166–175; Correlation analysis of reactivity in the oxidation of anilines by nicotinium dichromate in nonaqueous media. 38, 657–665 (2006); Solvent hydrogen bonding and structural effects on nucleophilic substitution reactions: Part 3. Reaction of benzenesulfonyle chloride with anilines in benzene/propan-2-ol mixtures. 39, 657–663 (2007) (2006).

- 26.Mansoor, S. S. & Shafi, S. S. Oxidation of aniline and some para-substituted anilines by benzimidazolium fluorochromate in aqueous acetic acid medium-A kinetic and mechanistic study. Arab. J. Chem.7, 171–176 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guesmi, N. E., Boubaker, T. & Goumont, R. Activation of the aromatic system by the SO2CF3 group: kinetics study and structure-reactivity relationships. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 42, 203–210 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhahri, N., Boubaker, T. & Goumont, R. Mechanism and linear free energy relationships in Michael-type addition of 4-substituted anilines to activated olefin in acetonitrile. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 45, 763–770 (2013).

- 29.Salah, S. B., Boubaker, T. & Goumont, R. Kinetic studies on nucleophilic addition reactions of 4-X-substituted anilines to N 1-methyl-4-nitro-2,1,3 benzothiadiazolium tetrafluoroborate in acetonitrile: reaction mechanism and mayr’s approach. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 47, 461–470 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansoor, S. S., Shafi, S. S. & Ahmed, S. Z. Correlation analysis of reactivity in the oxidation of gome para-substituted benzhydrols by triethylammonium chlorochromate in non-aqueous media. Arab. J. Chem.10, S1129–S1137 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed, S. A. et al. Photochromism of dihydroindolizines part XIX. Efficient one-pot solid-state synthesis, kinetic, and computational studies based on dihydroindolizine photochromes†. J. Phys. Org. Chem.30, e3614–e3625 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karunakaran, C., Karuthapandian, S. & Suresh, S. Kinetic evidence of a common mechanism in the oxidations of diethyl sulfide by dichromates and halochromates of heterocyclic bases. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 35, 1–8 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, L. & Guo, Q-X. Isokinetic relationship, isoequilibrium relationship, and enthalpy-entropy compensation. Chem. Rev.101, 673–696 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linert, W. & Jameson, R. F. The isokinetic relationship. Chem. Soc. Rev.18, 477–505 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yelon, A., Sacher, E., Linert, W. & Barrie, P. J. Comment on “The mathematical origins of the kinetic compensation effect” parts 1 and 2 by P. J. Barrie, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 318 and 327 (2012). Phys Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 8232–8234 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Pan, A., Biswas, T., Rakshit, A. K. & Moulik, S. P. Enthalpy-Entropy compensation (EEC) effect: a revisit. J. Phys. Chem. B119, 15876–15884 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan, A., Kar, T., Rakshit, A. K. & Moulik, S. P. Enthalpy-Entropy compensation (EEC) effect: decisive role of free energy. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 10531–10539 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Shpan’ko, I. & Sadovaya, I. Enthalpy-entropy compensation effect and other aspects of isoparametricity in reactions between trans-2,3-bis(3-bromo-5-nitrophenyl)oxirane and arensulfonic acids. Reac. Kinet. Mech. Cat. 123, 473-484 (2018); Compensation effect in reactions between trans-4,4’-dinitrostilbene oxide and arylsulfonic acids. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 90, 2332-2338 (2016); Isoparametricityphenomenon and kinetic enthalpy-entropy compensation effect: experimental evidence obtained by investigating pyridine-catalyzed reactions of phenyloxirane with benzoic acids. Kinet. Catal. 55, 56-63 (2014).

- 39.Garvin, A., Augusto, P. E. D., Ibarz, R. & Ibarz, A. Kinetic and thermodynamic compensation study of the hydration of faba beans (vicia faba L.). Food Res. Int. 119, 390–397 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Ibarz, R., Garvin, A. & Ibarz, A. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of the photochemical degradation of patulin. Food Res. Int. 99, 348–354 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Garvin, A., Ibarz, R. & Ibarz, A. Kinetic and thermodynamic compensation. A current and practical review for foods. Food Res. Int. 96, 132–153 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. Simple regression. Nat. Methods12, 999–1000 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bewick, V., Cheek, L. & Ball, J. Statistics review 7: correlation and regression. Crit. Care7, 451–459 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craig, B. A., Moore, D. S. & McCabe, G. P. Introduction to the Practice of Statistics 6th edn (W. H. Freeman and Company, 2009).

- 45.SenGupta, K. K. & Chatterjee, U. Kinetics of oxidation of menthol, ethanol and isopropanol by hexachloroiridate IV. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem.43, 2491–2497 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelizzetti, E., Mentasti, E. & Baiocchi, C. Kinetics and mechanism of oxidation of quinols by hexachloroiridate (IV) in aqueous acidic perchlorate media. J. Phys. Chem.80, 2979–2982 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanbury, D. M. Reactions involving the hydrazinium free radical: oxidation of hydrazine by hexachloroiridate. Inorg. Chem.23, 2879–2882 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linert, W. Mechanistic and structural investigations based on the isokinetic relationship. Chem. Soc. Rev.23, 429–438 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leffler, J. E. The Interpretation of Enthalpy and Entropy Data. J. Org. Chem. 31, 533-537 (1966); The enthalpy-entropy relationship and its implications for organic chemistry. 20, 1202-1231 (1955).

- 50.Exner, O. Determination of the Isokinetic Temperature. Nature 227, 366-367 (1970); Concerning the Isokinetic Relationship. 201, 488-490 (1964); The enthalpy-entropy relationship in organic reactions. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 40, 2762-2780 (1975); Entropy–enthalpy compensation and anticompensation: solvation and ligand binding. Chem. Commun. 1655-1656 (2000).

- 51.Pearson, R. G. Influence of the solvent on rates of ionization, entropies, and heats of activation. J. Chem. Phys.20, 1478–1480 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linert, W. The isokinetic relationship. X. Experimental examples to the relationship between isokinetic temperatures and active heat bath frequencies. Chem. Phys.129, 381–393 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammett, L. P. Physical Organic Chemistry 1st edn (McGraw Hill, 1940).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.