Abstract

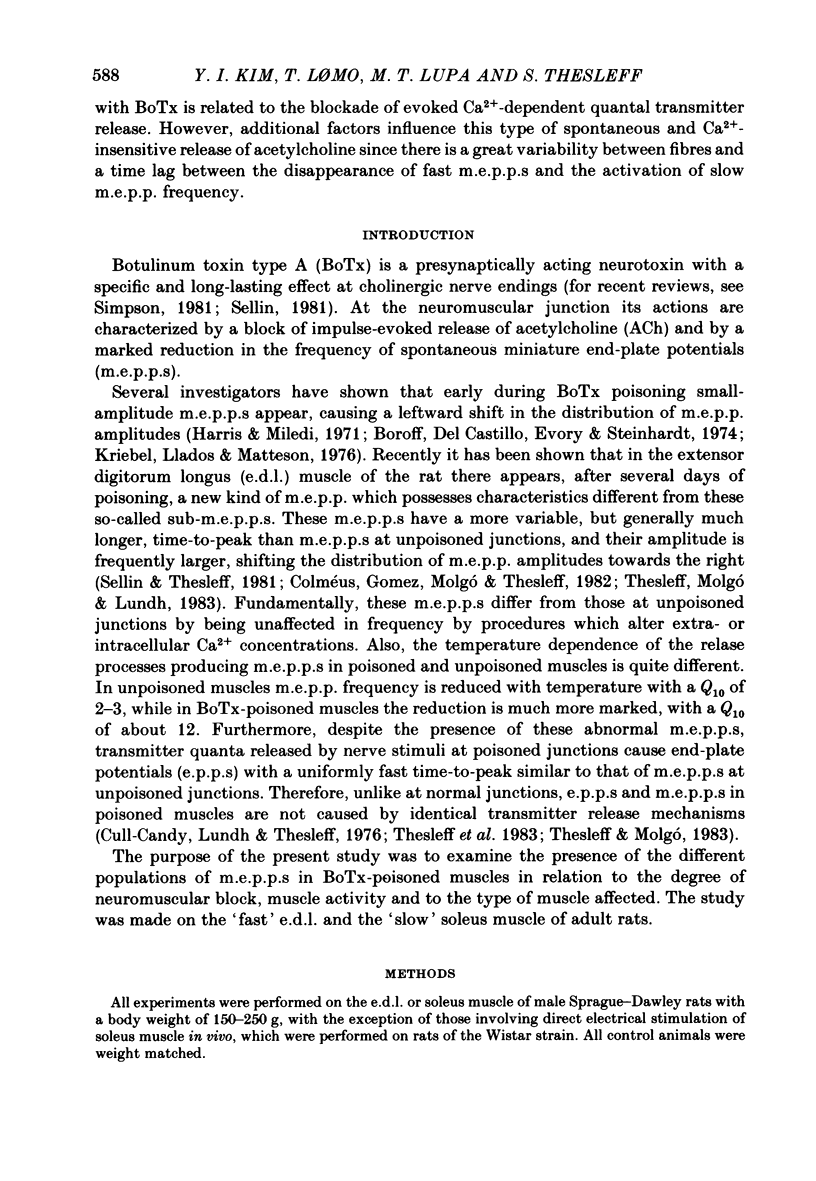

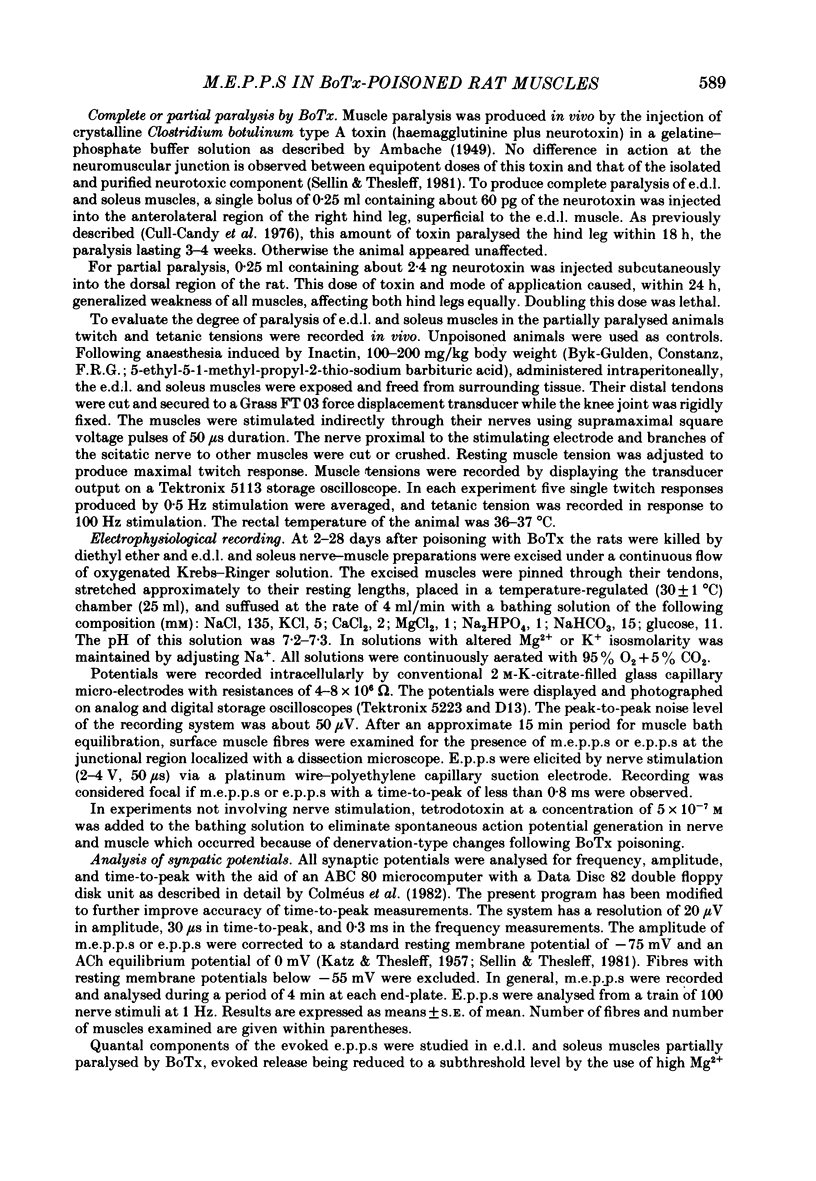

Spontaneous transmitter release, recorded as miniature end-plate potentials (m.e.p.p.s), was studied in rat extensor digitorum longus (e.d.l.) and soleus muscles partially or completely paralysed by botulinum toxin type A (BoTx). Normal unpoisoned muscles were examined for comparison. Analysis of m.e.p.p.s in both normal and BoTx-poisoned muscles confirmed the presence of two populations of potentials. One population, which comprised about 96% of the m.e.p.p.s recorded at non-poisoned end-plates, was characterized by a uniform time course and a mean time-to-peak of 0.5-0.7 ms. These potentials had a shape and time-to-peak similar to that of quantal end-plate potentials (e.p.p.s) evoked by nerve stimuli. These were designated 'fast m.e.p.p.s'. The other population of m.e.p.p.s was characterized by a slower, more variable rise-time, the time-to-peak exceeding 1.1 ms, and generally a larger amplitude. These were designated 'slow m.e.p.p.s'. In both partial and complete paralysis by BoTx the frequency of fast m.e.p.p.s was reduced by more than 90% and the reduction lasted several weeks. After 6-10 days of poisoning the frequency of slow m.e.p.p.s gradually increased. The highest frequency of slow m.e.p.p.s (0.4 Hz) was recorded in the partially paralysed soleus muscle, the frequency being about ten times that at unpoisoned end-plates. In both partially paralysed muscles slow m.e.p.p. frequency returned towards normal 28 days after poisoning. A significant correlation (r = 0.67) was observed between the quantal content of e.p.p.s and the frequency of fast m.e.p.p.s in partially paralysed e.d.l. muscles. No significant correlation was observed between quantal content of e.p.p.s and the frequency of slow m.e.p.p.s. To further study if muscle activity influenced the appearance of slow m.e.p.p.s, partially paralysed soleus muscles were directly stimulated in vivo during the first 11-13 days following BoTx poisoning, using a stimulation pattern which inhibits nerve terminal sprouting and the appearance of denervation changes. This procedure did not alter the frequency of slow m.e.p.p.s as compared to unstimulated poisoned controls. It is concluded that enhancement of slow m.e.p.p. frequency in muscles poisoned with BoTx is related to the blockade of evoked Ca2+-dependent quantal transmitter release. However, additional factors influence this type of spontaneous and Ca2+-insensitive release of acetylcholine since there is a great variability between fibres and a time lag between the disappearance of fast m.e.p.p.s and the activation of slow m.e.p.p. frequency.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ambache N. The peripheral action of Cl. botulinum toxin. J Physiol. 1949 Mar 15;108(2):127–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. R., McLachlan E. M., Taylor R. S. The formation of synapses in reinnervated mammalian striated muscle. J Physiol. 1973 Sep;233(3):481–500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroff D. A., del Castillo J., Evoy W. H., Steinhardt R. A. Observations on the action of type A botulinum toxin on frog neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1974 Jul;240(2):227–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. C., Goodwin G. M., Ironton R. Prevention of motor nerve sprouting in botulinum toxin poisoned mouse soleus muscles by direct stimulation of the muscle [proceedings]. J Physiol. 1977 May;267(1):42P–43P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangiano A., Lømo T., Lutzemberger L., Sveen O. Effects of chronic nerve conduction block on formation of neuromuscular junctions and junctional AChE in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1980 Jul;109(3):283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colméus C., Gomez S., Molgó J., Thesleff S. Discrepancies between spontaneous and evoked synaptic potentials at normal, regenerating and botulinum toxin poisoned mammalian neuromuscular junctions. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982 Apr 22;215(1198):63–74. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S. G., Lundh H., Thesleff S. Effects of botulinum toxin on neuromuscular transmission in the rat. J Physiol. 1976 Aug;260(1):177–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S. G., Miledi R., Trautmann A. End-plate currents and acetylcholine noise at normal and myasthenic human end-plates. J Physiol. 1979 Feb;287:247–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL CASTILLO J., KATZ B. Quantal components of the end-plate potential. J Physiol. 1954 Jun 28;124(3):560–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R., Jansen J. K., Laing N. G., Tønnesen H. The innervation of skeletal muscles in chickens curarized during early development. J Neurocytol. 1983 Dec;12(6):887–919. doi: 10.1007/BF01153341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman D. B. Neurotrophic regulation of muscle cholinesterase: effects of botulinum toxin and denervation. J Physiol. 1972 Nov;226(3):619–627. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp010000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S., Duchen L. W., Hornsey S. Effects of x-irradiation on axonal sprouting induced by botulinum toxin. Neuroscience. 1982 Apr;7(4):1023–1036. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES R., WHALER B. C. Influence of nerve-ending activity and of drugs on the rate of paralysis of rat diaphragm preparations by Cl. botulinum type A toxin. J Physiol. 1962 Feb;160:221–233. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. J., Miledi R. The effect of type D botulinum toxin on frog neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1971 Sep;217(2):497–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen E., Jansson S. E., Tolppanen E. M. Independent release of supranormal acetylcholine quanta at the rat neuromuscular junction. Neuroscience. 1982 Jan;7(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume R. I., Role L. W., Fischbach G. D. Acetylcholine release from growth cones detected with patches of acetylcholine receptor-rich membranes. Nature. 1983 Oct 13;305(5935):632–634. doi: 10.1038/305632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J. K., Van Essen D. Proceedings: A population of miniature end-plate potentials not evoked by nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1976 Jun;258(2):103P–104P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATZ B., THESLEFF S. On the factors which determine the amplitude of the miniature end-plate potential. J Physiol. 1957 Jul 11;137(2):267–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel M. E., Llados F., Matteson D. R. Spontaneous subminature end-plate potentials in mouse diaphragm muscle: evidence for synchronous release. J Physiol. 1976 Nov;262(3):553–581. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LILEY A. W. Spontaneous release of transmitter substance in multiquantal units. J Physiol. 1957 May 23;136(3):595–605. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomo T., Westgaard R. H. Further studies on the control of ACh sensitivity by muscle activity in the rat. J Physiol. 1975 Nov;252(3):603–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLLS J. G. The electrical properties of denervated skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1956 Jan 27;131(1):1–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin L. C. The action of batulinum toxin at the neuromuscular junction. Med Biol. 1981 Feb;59(1):11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin L. C., Thesleff S. Pre- and post-synaptic actions of botulinum toxin at the rat neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1981 Aug;317:487–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. L. The origin, structure, and pharmacological activity of botulinum toxin. Pharmacol Rev. 1981 Sep;33(3):155–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterz R., Pagala M., Peper K. Postjunctional characteristics of the endplates in mammalian fast and slow muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1983 Jun;398(1):48–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00584712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. H., Poo M. M. Spontaneous release of transmitter from growth cones of embryonic neurones. Nature. 1983 Oct 13;305(5935):634–637. doi: 10.1038/305634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]