Abstract

Soluble, circulating Klotho (sKlotho) is essential for normal health and renal function. sKlotho is shed from the renal distal convoluted tubule (DCT), its primary source, via enzymatic cleavage. However, the physiologic mechanisms that control sKlotho production, trafficking, and shedding are not fully defined. We previously found that the G protein‐coupled calcium‐sensing receptor (CaSR) co‐localizes with membrane‐bound αKlotho and the disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM10 in the DCT and controls sKlotho in response to CaSR ligands and pHo by activating ADAM10. Here, we advance understanding of this process by showing that tetraspanin 5 (Tspan5), a scaffolding and chaperone protein, contributes to the cell surface expression and specificity of a protein complex that includes Tspan5, ADAM10, Klotho, and CaSR. These results support a model of multiprotein complexes that confer signaling specificity beyond CaSR on G protein‐coupled processes.

Impact statement.

Systemic circulating sKlotho is a determinant for normal physiology. Studies of knockout animals established its role as an anti‐aging protein. The regulatory mechanisms for Klotho production and secretion are largely unknown. We report that Tspan 5 contributes to CaSR‐ and ADAM10‐dependent Klotho shedding from the kidney, its primary source.

Keywords: ADAM10, calcim‐sensing receptor, distal convoluted tubule, Klotho, Tspan

The G protein‐coupled calcium‐sensing receptor (CaSR) and the disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM10 in the renal distal convoluted tubule control systemic levels of Klotho, a cell and tissue homeostasis‐preserving factor. We show that CaSR‐induced cleavage of membrane‐bound αKlotho by ADAM10 requires tetraspanin 5 (Tspan5), a scaffolding and chaperone protein. This work adds to understanding of the mechanisms that confer specificity on G protein‐coupled signaling processes.

Abbreviations

ADAM10, a disintegrin metalloprotease 10

C8Tspan, C8 family of Tspans

CaSR, calcium‐sensing receptor

DCT, distal convoluted tubule

FGFR1, FGF1 receptor

PTH, parathyroid hormone

Tspans, tetraspanins

The CaSR and Klotho participate in regulation of mineral metabolism, and their complex interactions in this area, often cell type‐specific, are not fully defined. αKlotho is a membrane‐bound protein primarily expressed in the kidney, parathyroid glands, and choroid plexus that also circulates when shed (soluble, circulating Klotho, sKlotho) from the renal Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT) [1]. In proximal tubule and parathyroid glands, αKlotho is expressed as a cell surface protein in a complex with the FGFR1 receptor. FGF‐23, increased in response to high PO4, binds to the Klotho‐FGFR1 complex in the proximal tubule to decrease PO4 reabsorption by NaPi2 and NaPic, and reduce calcitriol synthesis [2].

The CaSR is best known for regulation of parathyroid gland PTH secretion, synthesis, and gland growth, but it also has a prominent role in renal calcium transport. In the parathyroid glands, Klotho interacts with FGFR1 and the CaSR, where CaSR activation and Klotho suppress PTH secretion and parathyroid gland hyperplasia [3]. In the thick ascending limb of Henle, the CaSR regulates paracellular permeability to calcium and magnesium via claudin expression and transcellular ion transport via NKCC2 and ROMK [4]. In the DCT, the CaSR interacts with Kir4.1 and controls WNK4 and NCC to reduce transepithelial NaCl transport [5, 6, 7]. The CaSR in the DCT basolateral membrane also forms a complex with ADAM10 allowing CaSR‐regulated cleavage of membrane‐bound Klotho and control of sKlotho levels by CaSR activation in response to divalent cations as well as pHo [8].

sKlotho functions as an anti‐aging protein [9]. Klotho deficiency states including genetic knockout and progressive renal insufficiency have many characteristics of premature aging, including vascular calcification, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, muscle wasting, osteopenia, renal fibrosis and hyperphosphatemia. When supplemented experimentally in vivo, Klotho has beneficial effects ranging from improved cognition to heart and vascular health. Recovery from conditions with short‐term Klotho deficiency such as acute renal or lung injury also improves with Klotho supplementation [10, 11]. However, significant barriers to replacing Klotho with exogenously produced protein exist. The receptor or receptors for Klotho are not known, making small molecule agonists difficult to develop. The protein is 130 kDa, and difficult to synthesize in large quantities that are functional. Increasing expression of endogenous Klotho may be a strategy for increasing levels of sKlotho, but the regulatory mechanisms for Klotho production and secretion are largely unknown.

We previously found that the CaSR co‐localizes with Klotho in the DCT and contributes to regulation of Klotho shedding in vivo through ADAM10‐mediated cleavage [8]. Another group found that the CaSR and Klotho interact in parathyroid glands [3]. The CaSR, ADAM10, and Klotho co‐localize in mouse kidney and in heterologous expression systems. Although ADAM17 was reported to cleave Klotho, the effect of the CaSR is specific for ADAM10 [8, 12, 13, 14]. The cell surface distribution of these proteins changes with CaSR activation and is increased with inhibition of ADAM10, indicating that this mechanism involves active membrane trafficking, where the CaSR, Klotho, and ADAM10 form a multiprotein complex that may be transient. However, these three proteins are not recognized scaffolding proteins, and how they interact to confer CaSR‐activated Klotho shedding in the DCT is unknown.

Processing and trafficking of Klotho and the CaSR are not well‐characterized, but processing and maturation of ADAM10 are better understood. ADAM10 is a 748 AA, 84 kDa protein that is synthesized in an inactive form with a pro‐domain that is cleaved in the Golgi [15]. The mature protein has an extracellular domain with the Zn‐containing metalloproteinase, as well as disintegrin and cysteine‐rich domains. In the inactive conformation, the metalloproteinase domain folds into the cysteine‐rich domain in an auto‐inhibitory structure where the protease active site is inaccessible [16]. Maturation of ADAM10 depends on its interaction with a sub‐family of the tetraspanins (Tspans), a 33 member protein family that has four helical transmembrane domains and two asymmetric extracellular loops containing regions that contribute specificity to interactions with other proteins and substrates [17, 18]. Tspans have multiple essential functions, generally related to regulation of trafficking of their interacting proteins and organization of protein complexes in membranes [19]. ADAM10 associates with the C8 sub‐family of Tspans, which have eight cysteines in their large extracellular loops, and includes Tspan5, 10, 14, 15, 17, and 33 [20]. These proteins can have distinct and overlapping effects on ADAM10 function. The identity of the Tspan(s) that contribute to CaSR‐mediated Klotho cleavage by ADAM10 in the DCT is unknown. Given that Tspans are essential for ADAM10 trafficking and processing, we hypothesized that CaSR‐dependent Klotho shedding may involve Tspan‐dependent ADAM10 trafficking with the CaSR and Klotho.

Based on literature that shows regulation of ADAM10 by Tspan5 and 15, we investigated which of these Tspans is expressed in the DCT where the CaSR, Klotho, and ADAM10 interact and function, and determined their contribution to regulation of sKlotho shedding. We report that Tspan5 and not Tspan15 contributes to Klotho shedding by the CaSR, Klotho and ADAM10 complex. These studies expand past work on physiologic regulation of Klotho shedding by CaSR‐mediated mechanisms to include Tspan5 regulated ADAM10 trafficking and protein complex formation.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Animal research was performed in accordance with the UT Southwestern Medical Center Animal IACUC guidelines. The research study protocol (number 2014‐0078) was approved by the UT Southwestern Medical Center Animal IACUC (NIH OLAW Assurance Number A3472‐01). UT Southwestern Medical Center is fully accredited by the American Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Care, International (AAALAC). Animals are housed and maintained in accordance with the applicable portions of the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Veterinary care is under the direction of a full‐time veterinarian boarded by the American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine. Mice were sacrificed for experiments by first anesthetizing with Avertin and then euthanizing by cervical dislocation.

Tissue culture and immunoprecipitation studies

Currently, commercially available cell lines that express all the proteins of interest do not exist, and primary DCT cells that do, are not available in sufficient quantities for biochemical and functional studies. As CaSR and Klotho proteins are not expressed in cultured cell lines, we compared the transfection efficiency of siRNA and endogenous Tspan expression levels in 4 different cells lines of kidney origin (Fig. S3A,B). HEK293 cells that stably express the CaSR were identified to be the best cell line to use because they have stable expression of the CaSR at a level consistent with signaling fidelity [8], feature endogenous expression of both Tspan5 and 15, and are easy to transfect with plasmids and siRNA.

All cell lines used in this study were authenticated within the past 3 years by microscopy to confirm normal live‐cell morphology, and myoplasma‐free status after Hoechst 33258 staining.

HEK‐293 (RRID:CVCL_0045), cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma). For all studies, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp,, Carlsbad, CA, USA) unless stated otherwise, and used for experiments after 48 h. The expression plasmids for the full‐length Klotho were obtained from Dr. Makoto Kuro‐o, ADAM10 and 17 from ADDGENE, human CaSRWT were described previously [8]. Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer supplemented with HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

For immunoprecipitation studies, HEK‐293 cells stably expressing the HA‐tagged CaSRWT were transfected with a control GFP vector or full‐length Klotho. Protein G beads (ThermoFisher) were used to immunoprecipitate Klotho and associated proteins in complex from RIPA cell lysate supernatant fractions, following manufacturer's instructions. Immunoprecipitated proteins were denatured in LDS sample buffer with Reducing Solution, warmed to 37 °C for 10 min, and separated in 8% Bolt mini‐gels in a MES buffer system (ThermoFisher). Separated proteins were wet‐transferred to 0.2 mm pore size nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman PLC, Buckinghimshire, IK) using a plate electrode Bolt mini‐transfer system (ThermoFisher), then immunoblotted with specific antibodies using standard procedures at 4 °C. Antibodies used were: anti‐Klotho generated by Makoto Kuro‐o (KM2076, Cosmo bio, Carlsbad, CA, USA), anti‐ADAM10 (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), anti‐CaSR generated by our laboratory (Cell signaling Technology, Danvers, AM, USA), described previously.

For siRNA studies, plasmids and siRNA (20 nm) were co‐transfected with DharmaFECT Duo (Dharmicon Inc., Lafayette, CO, USA), following manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection of siRNA (ADAM10 siRNA smart pool: M‐004503‐02‐0005, ADAM17 siRNA smart pool: M‐003453‐01‐0005, Dharmicon, Negative control siRNA‐ABI). RNA was extracted using the Direct‐Zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA, USA), and cDNA reverse transcribed using SuperScriptT™ III First‐Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Gene KO efficiency was analyzed with specific primers using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, LLC, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and StepOnePlus™ Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For quantitative analysis, the samples were normalized to GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase) gene expression using the ΔΔC T value method.

Forward and reverse primer sequences for specific genes in 5′ to 3′ order are: hCaSR‐GCTCTTCACCAATGGCTCCTGT, CCACACTCATCAAAGGTCACCTG; hADMA10‐GAGGAGTGTACGTGTGCCAGTT, GACCACTGAAGTGCCTACTCCA; hTspan5‐ATGTGGCGTTCCATTCTCCTGC, CTGCAACCACTTCTCAAACTGGG; hTpan15‐GGACAACTACACCATCATGGCG, CCATCAGTGACAGAGTGCTCCA.

Measurement of shed klotho from HEK‐293 cells

For measurement of shed Klotho, 48 h post‐transfection, cells in 6 well dishes were washed 2× and cultured for 3 h (for calcium induced shedding) or 1 h (for drug treatments) in fresh serum‐free DMEM/F12 (1.0 mm calcium) in a humidified cell culture incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The time‐course for shed Klotho response was determined using high calcium and was linear between 1 and 3 h. The medium was collected and precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and processed for immunoblotting as previously described [8]. BSA (10 mg·mL−1) was added as carrier and co‐precipitated with the medium proteins. BSA in resolubilized proteins transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane was stained with Ponceau and used as loading control for shed Klotho immunoblot quantification.

Glycerol density gradient centrifugation

Mouse kidneys were homogenized in 10× volume of tissue homogenization buffer [50 mm MOPS, pH 7.4, 2 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 2% Brij 97, 1× HALT protease inhibitor mixture (ThermoFisher), 10 μm E64], with a ground glass homogenizer. Homogenates were incubated on ice for 30 min, pre‐cleared by centrifugation (20 000 g , 1 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant fraction was cleared by ultra‐centrifugation (100 000 g , 30 min at 4 °C). Clarified extracts (750 μg total protein determined by Bradford assay) were overlayed on 10–40% linear glycerol gradients (2 mL total volume) containing tissue homogenization buffer. Samples were centrifuged at 100 000 g for 3 h at 4 °C in a TLS55 rotor, and 100 μL fractions were collected for immunoblot analysis.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cultured HEK‐293 cells were transfected with CaSR and Klotho for 24 h, then reseeded onto glass coverslips and incubated for 24 h. For tissue staining, frozen OCT‐embedded kidney tissues were cut into 5 μm sections and fixed by immersing the slides in acetone/methanol (1 : 1) for 5 min (acetone/methanol prechilled to −20 °C). Then samples were washed 3 times in PBS, dried at RT and the tissue sections circled with an ImmEdge pen. One hundred microliter of blocking solution per tissue section was applied and incubated at RT for 30 min, incubated with specific primary antibodies and then the fluorescence‐labeled secondary antibodies using standard procedures.

Confocal imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM880 with Airyscan laser scanning microscope equipped with Plan‐Apochromat 10×/0.3 NA, 20×/0.8 NA, 25×/0.8 NA, and 63×/1.40 NA oil‐immersion objective (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany). Experiments were performed at constant room temperature. Images or regions of interest (ROIs) were further processed with zen 2.6 (blue edition) software (Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, White Plains, NY, USA).

Statistics

For all statistical analyses, graphpad prism (Graphpad Software, Boston, MA, USA) was used. Comparisons of two groups were by T‐test, non‐parametric, 2‐tailed; comparisons of more than two groups were by ANOVA, with Dunnett's multiple comparisons post‐test against control. P value indications are noted throughout in figure legends. When multiple comparisons were made among all groups, selected comparisons are shown with lines within the graphical representation of mean ± SD. Each scatter dot in all graphs represents a distinct experimental N.

Results

Tspan5 and Tspan15 are expressed in the DCT where klotho is made and shed

Although the CaSR and Klotho are expressed in several renal tubule segments and cell types, we focused on the DCT because both are expressed at high levels in that segment and it is the source of sKlotho [1]. Based on single nucleus RNA sequencing analysis by the Humphreys lab at Washington University (http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/), Tspans 5, 14, 15, and 33 are expressed in the DCT, while Tspan 10 is not expressed and Tspan 17 appears to be expressed at negligible levels. We focused on Tspans 5 and 15 because these two proteins confer different substrate specificities on ADAM10, the functions of Tspan5 and 14 overlap, and the functions of Tspan15 and 33 overlap [21, 22].

Comparisons of renal cortex frozen sections stained for Tspan5 and 15 with Klotho were performed using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1) [8]. The high level of Klotho expression in the DCT allows Klotho to be used as a marker for this nephron segment. At the 2D level, greater intensity of co‐localized signals (yellow) is visible for Tspan5 (green) and Klotho (red) staining (Fig. 1A) compared to Tspan15 and Klotho (Fig. 1B). Tspan5 staining is punctate in the cytoplasm and densest around the nuclei, while Tspan15 staining is also punctate, but diffuse in the cytoplasm. Klotho staining is diffusely punctate in the cytoplasm with perinuclear concentration. In the merged panels, overlap of Tspan5 and Klotho is evident from yellow punctate staining concentrated in a perinuclear distribution.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of mouse renal cortical protein expression in distal convoluted tubules. Frozen sections of mouse kidney cortex were incubated with antibodies recognizing Klotho (red) and (A) Tspan5 (green, upper) or (B) Tspan15 (green, lower) and imaged with confocal microscopy. Merged‐images (third column) show overlap of the two colors, with selected boxed areas that were magnified and shown with rendered 3‐D stack images (last column). Rendered 3‐D Z‐stacks are shown to highlight the overlap of Tspan5 and Klotho staining (yellow) and the significantly reduced overlap of Tspan15 and Klotho. Scale bar = 5 μm. Representative images were selected from at least 3 technical replicates.

Enlargements of selected boxed regions and visualization by 3D rendered Z‐stack images (last column of figures in Fig. 1A,B), show partial Tspan5 and Klotho overlap, indicating that Tspan5 is also present in regions of the cell that lack Klotho (Fig. 1A). Consistent with 2D images, Tspan15 shows reduced overlap with Klotho staining in 3D rendered Z‐stack images. The extent of co‐localization suggests that Tspan5 is a better candidate than Tspan15 for physiologic interaction with Klotho, the CaSR, and ADAM10 in the renal cortex, which we confirmed are co‐expressed (Fig. S1, Fig. S2).

Tspan5 depletion decreases cell surface expression of klotho and CaSR

Based on comparable expression levels of Klotho, the CaSR, and ADAM10 that were measured by immunoblots or qRT‐PCR in renal cortical tissue [8], we hypothesized that differential effects on shed Klotho could be attributed to Tspan5‐associated trafficking of Klotho rather than regulation of its expression. To test the hypothesis that Tspan5 and Tspan15 have distinct effects on Klotho trafficking to the cell surface affecting Klotho shedding, we compared immunofluorescence images of comparable numbers of non‐permeabilized cells that were transfected with siRNAs targeting Tspan5 or 15. Markedly reduced cell surface localization of Tspan5, Klotho, and the CaSR is observed in HEK‐293 cells that had been transfected with si‐Tspan5 (Fig. 2A). The cell surface localization of Klotho and CaSR appears unaffected by the control si‐NC and si‐Tspan15 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Tspan5 depletion decreases cell surface expression of Klotho and the CaSR. HEK‐293 cells that stably express the CaSR were transiently transfected with Klotho in the presence of endogenous Tspan5, 15, and ADAM10 proteins. Cells were transfected with non‐specific control siRNA (si‐NC), siRNA directed against Tspan5 (si‐T5), or Tspan15 (si‐T15), grown on coverslips, and studied after 2 days. Cells were fixed under non‐permeabilizing conditions and stained with antibodies to Tspan5 or Tspan15 (green), Klotho (red) and the CaSR (magenta). (A) Enlarged merged‐images of cells transfected with si‐NC (left set of panels) or si‐T5 (right set of panels), show marked reduction in Tspan5, Klotho, and CaSR immunofluorescence. (B) Enlarged merged‐images of cells transfected with si‐NC (left set of panels) or si‐T15 (right set of panels), show reduced green Tspan15 immunofluorescence, without significant reduction in Klotho or CaSR immunofluorescence. Scale bar is 5 μm. Split images are shown below respective enlarged merged‐images. Images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Depletion of Tspan5 but not Tspan 15 attenuates CaSR‐stimulated klotho shedding

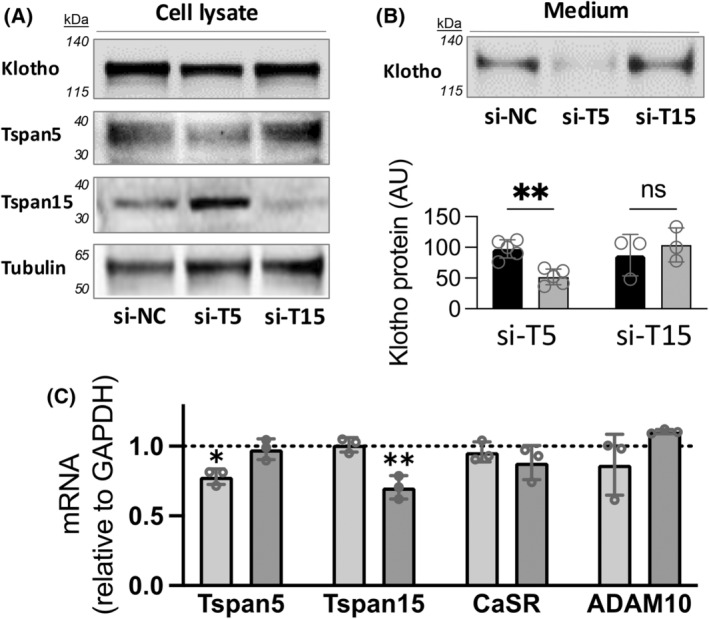

Based on co‐localization studies, we asked whether Tspan 5 is important for the formation of functional protein complexes among the CaSR, Klotho, and ADAM10. We hypothesized that reduced Tspan5 could impair CaSR‐stimulated Klotho shedding. To test this hypothesis, we targeted endogenous Tspan 5 or 15 using siRNA and measured the effects on CaSR‐stimulated Klotho shedding in response to CaSR activation (Fig. 3). Total Klotho protein expression in cell lysates (Fig. 3A) was similar in all three groups. Tspan5 reduction led to significant blunting of CaSR‐stimulated Klotho shedding to 52 ± 13% of control levels (Fig. 3B, black bar, N = 5, **P < 0.001). However, reduced expression of Tspan15 has no significant effect on compared to controls. Cells that were transfected with control (si‐NC) or targeted siRNA (si‐T5 or si‐T15), show significant reductions in the targeted mRNAs, but not stably expressed CaSR or endogenous ADAM10 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Cell surface depletion of Tspan5 but not Tspan 15 reduces CaSR‐stimulated Klotho shedding. HEK‐293 cells that stably express the CaSR, endogenous Tspan5, 15, and ADAM10 and transiently express Klotho were transfected with non‐specific control siRNA (si‐NC), siRNA directed against Tspan5 (si‐T5), or Tspan 15 (si‐T15), and studied after 2 days. (A) Representative immunoblots of cell extracts showing expression levels of Klotho, Tspan5, or Tspan15 compared to Tubulin. Klotho expression after transfection were comparable (upper panel), and total Tspan5 and Tspan 15 proteins were partly reduced by respective siRNA. (B) Representative immunoblot of Klotho shed in 3 h of incubation in R‐568 (CaSR‐activator) supplemented tissue culture medium. Quantification of shed Klotho from at least 3 independent experiments (open circles) performed in different weeks, is shown below; **P < 0.001 by ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons post‐test using graphpad prism. (C) Quantification of mRNA for Tspan5, Tspan15, the CaSR, and ADAM10 by qRT‐PCR after transfection of siRNA reagents. The GAPDH‐normalized levels of indicated mRNA are shown, relative to si‐NC (dotted line), after transfection with si‐T5 (light gray bars) or si‐T15 (dark gray bars); N = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, by 2‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test against si‐NC control using graphpad prism.

Co‐fractionation and co‐immunoprecipitation studies support transient interaction of klotho and Tspan5

Based on biochemical work by others, our Klotho shedding experiments (Fig. 3), and previous work, Tspan5 should contribute to protein complex formation by ADAM10, the CaSR, and Klotho [8]. To determine whether Tspan5 also interacts with Klotho to bring ADAM10 into proximity for cleavage, we first examined whether Tspan5 co‐fractionates with ADAM10 and Klotho in a glycerol density gradient using a mouse kidney cortex extract. All proteins of interest, the CaSR, Klotho, ADAM10, and Tspan5 are found in overlapping fractions (Fig. 4A), in agreement with our fluorescence microscopy images (Fig. 1, Fig. S2). Tspan15 was not detectable by immunoblotting the soluble fraction of mouse kidney cortex homogenized in buffer with 2% Brij 97 for co‐fractionation studies (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Co‐immunoprecipitation and co‐fractionation studies support transient interactions among Klotho, the CaSR, ADAM10, and Tspan5. (A) Glycerol density gradient fractionation of mouse kidney extracts. Fraction numbers are shown at the top of the panels. Representative immunoblot images for the CaSR, Klotho, ADAM10, and Tspn5 are shown for each protein and each fraction. The CaSR co‐fractionates with Klotho, ADAM10, and Tspan5. (B) Co‐immunoprecipitation of Klotho, ADAM10, and the CaSR from kidney cortex extracts. The lanes from left to right are: total input used, IP with control IgG and Protein G beads (IP‐IgG(G)), IP with Klotho antibody and Protein G beads (IP‐KL(G)), unbound fraction from IP‐IgG (UnB‐IgG) and unbound fraction from IP‐KL (UnB‐KL). Representative results from N = 4 experiments are shown.

As an additional test for protein interactions in kidney tissue, immunoprecipitation experiments were carried out using the supernatant fractions of mouse kidney cortex homogenized in the presence of 2% Brij 97, and antibodies directed against a control IgG or Klotho (Fig. 4B). We find a weak, but distinct band that corresponds to Tspan5 in the Klotho‐IP fraction, that supports the hypothesis that these complexes may transiently associate for cleavage of Klotho. ADAM10 also co‐IPs with Klotho, Tspan5, and the CaSR.

Discussion

Ligand‐receptor signaling is the first step in what are recognized as increasingly complex systems to control biologic processes. Understanding these mechanisms is important for developing new therapeutic approaches with minimal off‐target effects. In experimental model and purified protein systems, signaling pathways that regulate ADAM proteases appear to have broader substrate specificity than is observed in vivo. ADAM10 and 17 both cleave Klotho in response to insulin in cultured cells, but in renal tissue and HEK‐293 cells expressing the CaSR, ADAM10 rather than ADAM17 is the biologically relevant enzyme [8, 12]. This result may be explained by the association of ADAM10 with C8Tspans as opposed to Rhomboid proteins that preferentially associate with ADAM17. In this work, we find that Tspan5 associates with the CaSR, Klotho, and ADAM10 to facilitate cell surface expression of the CaSR and CaSR‐stimulated Klotho cleavage, while Tspan 15, another C8Tspan that also associates with ADAM10 and facilitates its cleavage of N‐Cadherin and Platelet Glycoprotein VI, appears to have no role [17].

Tspan 5 and 15 have different patterns of expression in DCT cells and cultured HEK‐293 cells. While both proteins have punctate distributions in the cytoplasm and on the cell surface, suggesting that they are associated with vesicles or membrane sub‐domains, in permeabilized cells, we found that Tspan5 also appears in a much denser perinuclear pattern suggesting ER association. This pattern is shared with Klotho, the CaSR, and ADAM10, and is consistent with post‐translational association of these proteins in complexes or vesicles. Immunofluorescence imaging of non‐permeabilized cells shows Tspan5‐specific reduction in cell surface localization of these proteins following Tspan5 or 15 depletion. These observations are consistent with reduced cell surface protein complexes after CaSR activation with high Ca2+ and collectively support Tspan5‐mediated trafficking of protein complexes to the membrane where Klotho is cleaved and shed by ADAM10 [8].

Mouse DCT cells express C8Tspans 5, 14, 15, and 33, negligible levels of Tspan17, and do not express Tspan10 based on single nucleus sequencing analysis by the Humphreys lab at Washington University (http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/). Tspans 10 and 17 are not involved in cell surface expression of ADAM10 [21]. Tspans5 and 15 are better‐studied than the other C8 Tspans, and principles found in their study probably apply to other members of the group. Tspans 5 and 15, and ADAM10 support each other's exit from the ER and cell surface expression. Most of the ADAM10 in cells is bound to a C8 Tspan, and C8 Tspans interact with ADAM10 through sequences in their Large Extracellular Loops (LELs) [23, 24, 25].

C8Tspans contribute to the substrate specificity of ADAM10. With Tspan 5, ADAM10 cleaves Notch, and with Tspan15, it cleaves N‐cadherin. The functions of Tspan5 and 14, and Tspans 15 and 33 appear to overlap giving ADAM10 similar substrate specificity with each pair of Tspans. Although we cannot exclude participation of Tspan14 or 33 in CaSR‐mediated Klotho shedding, the magnitude of the effect of Tspan5 depletion and lack of effect of Tspan15 depletion on Klotho shedding (Fig. 3) suggest that Tspan 5 is the predominant Tetraspanin involved in CaSR‐ADAM10‐Klotho trafficking and cleavage. Our immunofluorescence and immunopreciptiation results showing separate localization and partial co‐immunoprecipitation of Klotho, the CaSR, and ADAM10 as well as overlapping localization indicates that these proteins have additional partners, so mechanisms controlling Klotho shedding that are independent of the CaSR probably exist.

Tetraspanins form microdomains, known as Tspan webs, through homo‐ and heteromeric lateral interactions with other tetraspanins and interactions with specific partners such as ADAM10 [26]. Proteomic studies using immunoprecipitation of ADAM10 from cells that over‐express Tspan5 or 15, or immunoprecipitation of Tspan15 from WT compared to Tspan15−/− HEK‐293 cells show that the two Tspans with ADAM10, and when immunoprecipitated individually, associate with overlapping, as well as distinct groups of proteins. The most common interactions are with the Tspan and ADAM10, but other Tspans, cytoskeletal proteins, adhesion proteins including integrins, syntaxins, metalloproteases, signaling proteins, scaffolding proteins, and other membrane proteins are also found [22, 23]. Some of these interactions may be low affinity, transient, or may be artifacts of cell disruption, but the finding that the composition of the groups differs depending on the Tspan involved indicates that some level of specificity is attributable to the individual Tspan. Tspan webs appear to be significant determinants of specificity in cell signaling and responses but understanding the processes by which they do so will be difficult.

A model for the mechanism by which Tspans restrict the broad substrate specificity of ADAM10 observed in vitro and over‐expression systems proposes that not only do membrane protein substrates have amino acid sequences that are specific for ADAM10, they also determine the distance of the ADAM10 protease site from the plasma membrane. Different Tspans bind ADAM10 and may guide the protease active site to varied distances above the plasma membrane that are specific to the Tspan and substrate. The interaction of ADAM10 with Tspan15 was characterized in detail at the structural level [17, 25]. The Tspan15 extracellular loop relieves autoinhibition of the catalytic domain and positions the ADAM10 active site 20 Å from the plasma membrane contributing to ADAM10 substrate selection, N‐cadherin in this example. Whether ADAM10 is regulated by Tspan5 via this mechanism to promote Klotho shedding is unknown. The lack of a clear ADAM10 consensus cleavage sequence(s) suggests that the distance of the cleavage site from the plasma membrane may be important in addition to amino acid sequence [27, 28, 29, 30]. Other factors including phosphatidyl serine membrane lipid content and additional proteins may also contribute to ADAM10 cleavage specificity [31, 32].

Our results provide evidence of sKlotho shedding that is stimulated by the CaSR, and that is mediated through trafficking and processing by ADAM10, Klotho, the CaSR, and Tspan5. Undoubtedly, other proteins and processes are involved in regulating sKlotho levels. One reason to pursue understanding of the regulatory mechanisms for substances like sKlotho is to manipulate them for therapeutic benefit. Two groups developed monoclonal antibodies directed at the large extracellular domains of Tspan5 and 15 that suppress ADAM10s cleavage activity [23, 24]. Presumably, these antibodies disrupt an essential structure or conformation. With increasing understanding of the proteins and structures involved in this system, monoclonal antibodies, diabodies, or other molecules could be designed that would stabilize an active conformation of the Klotho‐CaSR‐ADAM10‐Tspan5 complex and increase endogenous production of sKlotho [33].

Author contributions

ZL performed experiments and analyzed data, JY and EL performed experiments, ANC and RTM designed study, analyzed data and drafted paper.

Peer review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1002/1873‐3468.15078.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Localization of Tspan 5 and 15 in isolated mouse DCT.

Fig. S2. Tspan5 distribution in frozen renal cortex overlaps with Klotho and CaSR.

Fig. S3. Cell line selection for identification of Tspan that regulates Klotho shedding mediated by CaSR.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Merit Review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (BX004691), an Endowed Professor grant from the Jane and Charles Pak Center for Mineral Metabolism and Clinical Research at the UT Southwestern Medical School, and the VA North Texas Research Service.

Edited by Lukas Alfons Huber

Contributor Information

Audrey N. Chang, Email: audreyn.chang@utsouthwestern.edu.

R. Tyler Miller, Email: tyler.miller@utsouthwestern.edu.

Data accessibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author audreyn.chang@utsouthwestern.edu upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Addo T, Cho HJ, Barker SL, Ravikumar P, Gillings N, Bian A, Sidhu SS et al. (2016) Renal production, uptake, and handling of circulating αKlotho. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toka HR, Al‐Romaih K, Koshy JM, DiBartolo S 3rd, Kos CH, Quinn SJ, Curhan GC, Mount DB, Brown EM and Pollak MR (2012) Deficiency of the calcium‐sensing receptor in the kidney causes parathyroid hormone‐independent hypocalciuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 23, 1879–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fan Y, Liu W, Bi R, Densmore MJ, Sato T, Mannstadt M, Yuan Q, Zhou X, Olauson H, Larsson TE et al. (2018) Interrelated role of klotho and calcium‐sensing receptor in parathyroid hormone synthesis and parathyroid hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115, E3749–E3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sato T, Courbebaisse M, Ide N, Fan Y, Hanai JI, Kaludjerovic J, Densmore MJ, Yuan Q, Toka HR, Pollak MR et al. (2017) Parathyroid hormone controls paracellular Ca(2+) transport in the thick ascending limb by regulating the tight‐junction protein Claudin14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, E3344–E3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang C, Sindic A, Hill CE, Hujer KM, Chan KW, Sassen M, Wu Z, Kurachi Y, Nielsen S, Romero MF et al. (2007) Interaction of the Ca‐sensing receptor with the inwardly‐rectifying potassium channels Kir4.1 and Kir4.2 results in inhibition of channel function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292, F1073–F1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cha SK, Huang C, Ding Y, Qi X, Huang CL and Miller RT (2011) Calcium‐sensing receptor decreases cell surface expression of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1. J Biol Chem 286, 1828–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bazúa‐Valenti S, Rojas‐Vega L, Castañeda‐Bueno M, Barrera‐Chimal J, Bautista R, Cervantes‐Pérez LG, Vázquez N, Plata C, Murillo‐de‐Ozores AR, González‐Mariscal L et al. (2018) The calcium‐sensing receptor increases activity of the renal NCC through the WNK4‐SPAK pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 29, 1838–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoon J, Liu Z, Lee E, Liu L, Ferre S, Pastor J, Zhang J, Moe OW, Chang AN and Miller RT (2021) Physiologic regulation of systemic klotho levels by renal CaSR signaling in response to CaSR ligands and pH o. J Am Soc Nephrol 32, 3051–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuro‐o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E et al. (1997) Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu MC, Shi M, Gillings N, Lores B, Takahashi M, Kuro‐o M and Moe OW (2017) Recombinant a‐klotho may be prophylactic and therapeutic for acute to chronic kidney disease progression and uremic cardiomyopathy. Kidney Int 91, 1104–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jou‐Valencia D, Molema G, Popa E, Aslan A, van Dijk F, Mencke R, Hillebrands JL, Heeringa P, Hoenderop JG, Zijlstra JG et al. (2018) Renal klotho is reduced in septic patients and pretreatment with recombinant klotho attenuates organ injury in lipopolysaccharide‐challenged mice. Crit Care Med 46, e1196–e1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen CD, Podvin S, Gillespie E, Leeman SE and Abraham CR (2007) Insulin stimulates the cleavage and release of the extracellular domain of klotho by ADAM10 and ADAM17. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 19796–19801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perna AF, Pizza A, Di Nunzio A, Bellantone R, Raffaelli M, Cicchella T, Conzo G, Santini L, Zacchia M, Trepiccione F et al. (2017) ADAM17, a new player in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease‐mineral and bone disorder. J Ren Nutr 27, 453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Loon EPM, Pulskens WP, van der Hagen EAF, Lavrijsen M, Vervloet MG, van Goor H, Bindels RJM and Hoenderop JGJ (2015) Shedding of klotho by ADAMs in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309, F359–F368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrison N, Koo CZ and Tomlinson MG (2021) Regulation of ADAM10 by the TspanC8 family of tetraspanins and their therapeutic potential. Int J Mol Sci 22, 6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seegar TCM, Killingsworth LB, Saha N, Meyer PA, Patra D, Zimmerman B, Janes PW, Rubinstein E, Nikolov DB, Skiniotis G et al. (2017) Structural basis for regulated proteolysis by the α‐secretase ADAM10. Cell 171, 1638–1648.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipper CH, Egan ED, Gabriel KH and Blacklow SC (2023) Structural basis for membrane‐proximal proteolysis of substrates by ADAM10. Cell 186, 3632–3641.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Toribio V and Yáñez‐Mó M (2022) Tetraspanins interweave EV secretion, endosomal network dynamics and cellular metabolism. Eur J Cell Biol 101, 151229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt SC, Massenberg A, Homsi Y, Sons D and Lang T (2024) Microscopic clusters feature the composition of biochemical tetraspanin‐assemblies and constitute building‐blocks of tetraspanin enriched domains. Sci Rep 14, 2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noy PJ, Yang J, Reyat JS, Matthews AL, Charlton AE, Furmston J, Rogers DA, Rainger GE and Tomlinson MG (2016) TspanC8 tetraspanins and a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) interact via their extracellular regions: evidence for distinct binding mechanisms for different TspanC8 proteins. J Biol Chem 291, 3145–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dornier E, Coumailleau F, Ottavi JF, Moretti J, Boucheix C, Mauduit P, Schweisguth F and Rubinstein E (2012) TspanC8 tetraspanins regulate ADAM10/Kuzbanian trafficking and promote notch activation in flies and mammals. J Cell Biol 199, 481–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jouannet S, Saint‐Pol J, Fernandez L, Nguyen V, Charrin S, Boucheix C, Brou C, Milhiet PE and Rubinstein E (2016) TspanC8 tetraspanins differentially regulate the cleavage of ADAM10 substrates, notch activation and ADAM10 membrane compartmentalization. Cell Mol Life Sci 73, 1895–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koo CZ, Harrison N, Noy PJ, Szyroka J, Matthews AL, Hsia HE, Müller SA, Tüshaus J, Goulding J, Willis K et al. (2020) The tetraspanin Tspan15 is an essential subunit of an ADAM10 scissor complex. J Biol Chem 295, 12822–12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saint‐Pol J, Billard M, Dornier E, Eschenbrenner E, Danglot L, Boucheix C, Charrin S and Rubinstein E (2017) New insights into the tetraspanin Tspan5 using novel monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem 292, 9551–9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lipper CH, Gabriel KH, Seegar TCM, Dürr KL, Tomlinson MG and Blacklow SC (2022) Crystal structure of the Tspan15 LEL domain reveals a conserved ADAM10 binding site. Structure 30, 206–214.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Broadbent LM, Rothnie AJ, Simms J and Bill RM (2024) Classifying tetraspanins: a universal system for numbering residues and a proposal for naming structural motifs and subfamilies. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1866, 184265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dolla G, Nicolas S, Dos Santos LR, Bourgeois A, Pardossi‐Piquard R, Bihl F, Zaghrini C, Justino J, Payré C, Mansuelle P et al. (2024) Ectodomain shedding of PLA2R1 is mediated by the metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17. J Biol Chem 300, 107480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen CD, Li Y, Chen AK, Rudy MA, Nasse JS, Zeldich E, Polanco TJ and Abraham CR (2020) Identification of the cleavage sites leading to the shed forms of human and mouse anti‐aging and cognition‐enhancing protein klotho. PLoS One 15, e0226382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen CD, Tung TY, Liang J, Zeldich E, Tucker Zhou TB, Turk BE and Abraham CR (2014) Identification of cleavage sites leading to the shed form of the anti‐aging protein klotho. Biochemistry 53, 5579–5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lokau J, Nitz R, Agthe M, Monhasery N, Aparicio‐Siegmund S, Schumacher N, Wolf J, Möller‐Hackbarth K, Waetzig GH, Grötzinger J et al. (2016) Proteolytic cleavage governs Interleukin‐11 trans‐signaling. Cell Rep 14, 1761–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bleibaum F, Sommer A, Veit M, Rabe B, Andrä J, Kunzelmann K, Nehls C, Correa W, Gutsmann T, Grötzinger J et al. (2019) ADAM10 sheddase activation is controlled by cell membrane asymmetry. J Mol Cell Biol 11, 979–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abraham CB, Xu L, Pantelopulos GA and Straub JE (2023) Characterizing the transmembrane domains of ADAM10 and BACE1 and the impact of membrane composition. Biophys J 122, 3999–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Board NL, Yuan Z, Wu F, Moskovljevic M, Ravi M, Sengupta S, Mun SS, Simonetti FR, Lai J, Tebas P et al. (2024) Bispecific antibodies promote natural killer cell‐mediated elimination of HIV‐1 reservoir cells. Nat Immunol 25, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Localization of Tspan 5 and 15 in isolated mouse DCT.

Fig. S2. Tspan5 distribution in frozen renal cortex overlaps with Klotho and CaSR.

Fig. S3. Cell line selection for identification of Tspan that regulates Klotho shedding mediated by CaSR.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author audreyn.chang@utsouthwestern.edu upon reasonable request.