Abstract

Accumulated senescent cells during the aging process are a key driver of functional decline and age-related disorders. Here, we identify ganoderic acid A (GAA) as a potent anti-senescent compound with low toxicity and favorable drug properties through high-content screening. GAA, a major natural component of Ganoderma lucidum, possesses broad-spectrum geroprotective activity across various species. In C. elegans, GAA treatment extends lifespan and healthspan as effectively as rapamycin. Administration of GAA also mitigates the accumulation of senescent cells and physiological decline in multiple organs of irradiation-stimulated premature aging mice, natural aged mice, and western diet-induced obese mice. Notably, GAA displays a capability to enhance physical function and adapts to conditional changes in metabolic demand as mice aged. Mechanistically, GAA directly binds to TCOF1 to maintain ribosome homeostasis and thereby alleviate cellular senescence. These findings suggest a feasible senotherapeutic strategy for protecting against cellular senescence and age-related pathologies.

Subject terms: Senescence, Drug development, Translational research

Cellular senescence contributes to organismal aging and the onset of age-related diseases. Here the authors identify ganoderic acid A (GAA) as an anti-senescent compound by high-content screening, and report that it increases healthspan in C. elegans and in mice.

Introduction

The unprecedented global trends in population aging pose incessant challenges for maintaining late-life quality and controlling the healthcare costs of human aging1–4. Statistically, the proportion of people aged 65 and older is projected to increase from 1 in 11 in 2019 to 1 in 6 in 20505. Over recent years, abundant antiaging strategies have emerged to promote healthy aging, such as calorie restriction, rapamycin, metformin, and senolytics6. However, the complexity and heterogeneity of the aging process led to the tendency of disorders to occur in synchrony as multimorbidities in old age7. It is still crucial to discover different ways to compress the morbidity period of disease clusters to ensure the continued health of the elderly population.

Cellular senescence plays a pivotal role in organismal aging and the onset of age-related diseases. It is characterized by a cessation of the cell cycle, an increased resistance to apoptosis, and the secretion of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)8–10. Researchers reported that the transplantation of senescent cells into young mice was sufficient to cause a dose-dependent decline in body function11. Conversely, employing genetic and pharmacological methods to eliminate senescent cells has been shown to improve a range of disorders, such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, and Alzheimer’s disease12–15. Targeting senescent cells is increasingly recognized as a mainstream antiaging strategy16. Among these senotherapeutics, senolytics, the therapeutic agents to kill senescent cells by promoting apoptosis, attracted much attention in recent years. Of note, most reported senolytics are effective in animals, but their application is limited by the specific cell types and substantial cytotoxicity17. Preventative strategies designed to delay or diminish cell senescence offer an alternative approach by circumventing the need to eliminate senescent cells while still yielding antiaging benefits. However, the development and application of preventive antiaging drugs have faced numerous challenges. These include the heterogeneity of senescent cells, the intricate nature of organ aging, the risk of drug-induced proliferation, the narrow therapeutic concentration window, and the limited variety of cells that can be targeted.6,18–20. Collectively, it is highly beneficial to create preventive senotherapies that offer a wider range of effectiveness and exhibit minimal toxicity. Such advancements would enhance existing antiaging strategies and ultimately foster healthy aging.

In this work, a high-content screening model is constructed to identify natural products with anti-senescent properties. After 3 rounds of rigorous screening, ganoderic acid A (GAA), a triterpenoid compound derived from Ganoderma lucidum21, is identified as an excellent natural senotherapeutic agent. GAA prevents senescence across broad cell types, and also extends the healthspan in C. elegans and several mouse models. Meaningfully, GAA exhibits low toxicity and does not activate abnormal proliferation in young cells and cancer cells. For the underlying mechanism, GAA directly binds to TCOF1 to maintain ribosomal homeostasis and accordingly guard against cellular senescence.

Results

High-content screening for natural products that prevent cellular senescence

With the ultimate goal of reducing the accumulation of cellular senescence preventatively, we took advantage of a high-content screening system to identify natural products through a three-step screening process (Fig. 1a). For the primary screening, we collected 805 natural products with potential anti-senescent effects and constructed a natural senescent IMR-90 cell model induced by replication. Initial senescent IMR-90 cells (SA-β-Gal+ cells <20%) were intervened for 3 days (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and the senescent phenotypes were analyzed by a high-content system (Fig. 1b). Compared to the vehicle group, 113 compounds were found to be cytotoxic to cause cell death; 167 compounds resulted in an increase in the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells; and 371 compounds did not significantly reduce the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells (P > 0.05). Finally, the study encompassed 112 natural products, among which rapamycin, fisetin, flavone, and vitamin C are widely recognized as effective anti-senescence compounds (Fig. 1c). Further analyses showed that 47 compounds hit the criteria of reducing the proportion of SA-β-Gal+ cells to below 70% of the DMSO control group (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1. Identification of the anti-senescence natural product by high-content screening.

a Experimental scheme of the high-content screening strategy. b High-content imaging of young and natural senescent IMR-90 cells (SEN) induced by replication (n = 3 independent experiment). A merger by bright-field and fluorescence images. c Three-dimensional diagram of high-content analyses among 112 natural products with the treatment for 3 days. X axis: cell number; Y axis: SA-β-Gal; Z axis: nuclear area. Fold change (FC) was the ratio of natural products-treated groups to DMSO-treated groups. Vitamin C, flavone, and emodin had the best-improved effects on the nuclear area, cell number, and SA-β-Gal respectively. Rapamycin and fisetin were classic senotherapeutics. d Heatmap showing the senescence-related indicators in IMR-90 with the treatment of 47 candidate natural products. The indicators were displayed as SA-β-Gal, nuclear area, cell number, cell area, and cell width-length ratio. e SA-β-Gal expression in senescent HUVECs models with the treatment of 47 candidate natural products. Models were induced by replication, H2O2, etoposide, and the above-mixed stimulus. The natural products that decreased SA-β-Gal expression in all 4 models were put on the right side of the frame. f The relative levels of SA-β-Gal expression altered by 11 compounds in four senescent models of HUVECs. Six candidate compounds with above 30% inhibition of SA-β-Gal levels in four senescent models were labeled in black lines, while others were in red lines. g Representative images and quantification of SA-β-Gal staining after the 4-day treatment of six compounds in senescent MEF cells with different concentrations (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 500, and 1000 μM). 0 μM: DMSO. (n = 3 independent experiment). h LDH release ratio in senescent MEF cells treated with different concentrations of six compounds. The asterisk indicates statistical significance between control and natural product-treated groups (n = 5 independent experiment). Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Considering the heterogeneity of senescent cell subtypes22, we established senescent models of HUVECs induced by replication, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, oxidative stress), etoposide (genotoxic stress), and the above-mixed stimulus in the second screening (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Among 47 compounds, 12 compounds reduced SA-β-Gal+ cells in all 4 senescent models (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1e). However, only 11 compounds also decreased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, increased cell counts, and decreased nuclear area compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Then, applying a selection threshold of senescence average inhibition rate ≥ 30% (reduction of the SA-β-Gal+ cells proportion) in 4 cell models, we identified 6 candidates for further evaluation (Fig. 1f).

The last round of screening was performed to analyze the range of effective and safe concentrations for candidate compounds on senescent cells. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were chosen for their elongated telomeres and expression of telomerase, indicating that their premature senescence is usually caused by factors like oxidative stress and oncogene activation, rather than telomere attrition23. Our investigation revealed that a large number of MEF cells died when exposed to high concentrations of the compounds (500–1000 μM). Of note, GAA treatment displayed low cytotoxic (0.1–1000 μM) and decreased the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells (0.1–100 μM) over a wide range of concentrations in natural senescent MEF cells (Fig. 1g, h and Supplementary Fig. 1d). Similar results were observed in natural senescent L02 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1e–g). In addition, GAA was also predicted to have lower toxicity compared to the other 6 compounds and adhere to Lipinski’s drug property guidelines, as indicated by ADMET analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1h, i). Overall, GAA was a natural product with low toxicity, stable anti-senescence effects, and pharmaceutical properties.

GAA improves aging-related phenotype in broader cell types and C. elegans

We then validated the widespread effects of GAA on different cell types of natural senescence. We constructed an additional ten-cell senescent model derived from mice, rats, or humans. These models encompassed preadipocytes (3T3-L1), muscle cells (C2C12 and L6), renal cells (HK-2 and HBZY-1), smooth muscle cells (MOVAS), cardiomyocytes (H9C2 and HL-1), primary mice hepatocytes (PMH), and primary stem cells (BMSCs). Compared to the senescent group exposed to DMSO, GAA intervention caused a decrease in SA-β-Gal+ cells by 5–65%, LDH release by 9–34%, and nuclear area by 5–23%, and an increase in EdU+ cells by 12–47% (Fig. 2a–d). These series of results suggested the universality of GAA’s role in preventing cellular senescence.

Fig. 2. GAA alleviates the senescence of various cells and the aging-related phenotype of C. elegans.

a Measurement of LDH release in natural senescent cells treated with 10 μM GAA treatment or DMSO (n = 6 independent experiments). b Representative images and quantification showing SA-β-Gal staining in young (Y), SEN (S), or GAA-treated SEN cells (G) (n = 3 independent experiments). c EdU staining and the statistics of EdU+ cells and d nuclear area in GAA-treated senescent cells or controls (n = 3 independent experiments). e Representative survival curve of worms treated with DMSO, rapamycin (100 μM), and GAA (10, 100, and 1000 μM). The mean and maximum lifespans were shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of six independent experiments. f Lifespan analyses of worms challenged by heat stress (30 °C) and g oxidative stress (1.5% H2O2) with the treatment for 7 days of DMSO, rapamycin (100 μM), and GAA (1000 μM). The mean and maximum lifespans were shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. h The levels of lipofuscin, ROS (DCFH-DA, 10 μM), and lipids (Nile Red, 10 μg/ml) in worms after 10 days of intervention with DMSO, rapamycin, and GAA (n = 3 independent experiments with ten nematodes for each experiment). i–k Physical function of worms after 10-day treatments (n = 3 independent experiments with 10 nematodes for each experiment); i Worms were observed the spontaneous or regular sinusoidal movement (Normal), irregular or uncoordinated movement (Sluggish), and movement only by touching (Immobile). j The swing frequency and k pharyngeal swallowing frequency were detected in worms within 1 minute. Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM or SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

To find out whether GAA also affected aging in other species, we conducted GAA treatment experiments on lower species and compared its effects with those of rapamycin treatment. As expected, rapamycin (100 μM) significantly extended the median (12%) and maximum lifespan (25%) of C. elegans (Fig. 2e). Similarly, GAA increased the median and maximum lifespan of the worm in a dose-dependent manner. At 10, 100, and 1000 μM, the mean lifespan increased by 5%, 6%, and 8%, and the maximum lifespan increased by 8%, 9%, and 26%, respectively (Fig. 2e). A meaningful antiaging therapy should prolong the period of healthy living (healthspan). We thus investigated the ability of aging worms to cope with adversity. Upon stimulating aged worms at 30 °C, treatments with rapamycin and GAA extended the mean lifespan by 23% and 35% and the maximum lifespan by 9% and 12% respectively, compared to those treated with DMSO treatment (Fig. 2f). The intervention of rapamycin and GAA also extended the mean lifespan by 18% and 12% and the maximum lifespan by 31% and 15% respectively in aging worms challenged by 1.5% H2O2 (Fig. 2g). Moreover, after feeding for 10 days, both rapamycin and GAA improved lipofuscin accumulation, ROS levels, lipid deposition, and SA-β-Gal levels in C. elegans (Fig. 2h). We then assessed the effect of the treatments on the physical function of worms. After 10 days of cultivation, 57% of the worms exhibited normal movement in the rapamycin-treated group and 43% in the GAA-treated group. In contrast, only 27% of the worms in the DMSO-treated group displayed similar movement (Fig. 2i). Rapamycin and GAA treatment considerably improved body bending and pharyngeal pumping rates per min compared to worms treated with vehicle (Fig. 2j, k).

GAA-treated mice and cells are free from abnormal proliferation and damage

We assessed the potential proliferation and toxicity in middle-aged mice after being fed a diet containing GAA for 3 months (Fig. 3a). During the experiment, GAA-treated mice had no abnormalities in appearance or behavior (Supplementary Fig. 2a). At the end of the experiment, GAA-treated mice showed significant increases in GAA levels in serum, heart, liver, kidney, and lung compared to mice fed without GAA (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). For biochemical analysis, there were no abnormal changes in the levels of creatine kinase-MB (CKMB), creatinine, alanine transaminase (ALT), and metabolic indicators in middle-aged mice after GAA feeding (Fig. 3c–e). Also, GAA treatment did not materially change the organ index, Ki67 expression of the liver, protein profile of the kidney, nor the pathological manifestations of multiple organs (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 2c–f). In vitro, no signs of excessive proliferation and injury were observed in various young cells treated with GAA for 48 h (Fig. 3g, h).

Fig. 3. GAA treatment does not cause abnormal proliferation or damage in middle-aged mice and tumor-bearing mice.

a Experimental procedures for 2-month-old C57BL/6J mice fed with a GAA-added diet (120 mg/kg) for 3 months. ND: normal diet. b Tandem mass spectrum of GAA and GAA contents detected in the heart, kidney, liver, lung, and serum of mice at the end of the experiment (n = 3 or 4 mice). c Biochemical analysis to measure organ function, including heart (CKMB), d kidney (creatinine), and e liver (ALT) (n = 10 mice). f Immunohistochemistry images and quantification of the marker for cell proliferation (Ki67) in the liver (n = 3 mice). g EdU+ cells and h LDH levels in a variety of young cells with the presence or absence of 10 μM GAA (n = 3 or 6 independent experiments). i Experimental scheme for 2-month-old C57BL/6J mice subcutaneously inoculated with Hep1-6 cells (5 × 106) and subsequent intraperitoneal administered with GAA (15 mg/kg·bw) or vehicle once every 3 days for 18 days. j Gross morphology and measures of tumor volume and tumor weight values of mice at the study endpoint (n = 9 mice). k Representative images and quantification of Ki67 expression (n = 3 mice). l Organ index (organ weight relative to body weight) in normal mice and tumor-bearing mice (n = 9 mice). m Representative images of crystal violet staining in cancer cells after GAA (10 μM) treatment for 48 h. The colonies of the cells were manipulated as black (n = 3 independent experiments). n Representative images of scratch assay in cancer cells after GAA (10 μM) treatment for 48 h (n = 3 independent experiments). The red line marked the outline after cell migration. Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

To further explore the proliferative effect of GAA, we established a liver cancer model by subcutaneous tumorigenesis (Fig. 3i). During the treatment with GAA, the weight and feeding behavior of mice were not abnormal (Supplementary Fig. 2g). Although the tumor weight and volume did not differ significantly, the proliferation capacity of the tumor was decreased by 50% in GAA-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice, as indicated by Ki67 expression (Fig. 3j, k and Supplementary Fig. 2h). The organ indexes were also improved, including lung, kidney, and pancreas (Fig. 3l). Moreover, GAA inhibited colony formation (e.g., Hep1-6 cells, KYSE410, and MCF-7) and migration (e.g., Hep1-6 cells and MCF-7) in a variety of cancer cells (Fig. 3m, n). Collectively, the proliferative effects of GAA were not reflected in young and cancer cells and mice.

GAA administration prevents aging-related phenotype in IR-exposed premature aging mice

To determine the anti-senescent effect of GAA on organisms, we selected irradiation-induced (IR) premature aging mice models with an acute accumulation of senescent cells. After administered the GAA prophylactically by gavage for 5 days, mice were induced into senescence by exposure to whole-body IR at a low dose (2.8 Gy, 1 Gy/min). Subsequently, mice were given the geroprotective treatment of GAA or dasatinib plus quercetin (DQ), a classic senolytic, once per 3 days (Fig. 4a). Mice undergoing IR manifested slow weight gain initially. After 25 days, mice exhibited a dramatic weight decline, the loss of splenic germinal centers, and the death of spermatocytes (Fig. 4b, c). GAA treatment partially rescued splenic and testicular damage in IR mice, but high-frequency DQ therapy revealed more severe pathological damage in the testicles (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Fig. 4. The treatment of GAA or DQ alleviates aging-related disorders of mice exposed to IR.

a Experimental scheme. Mice were subjected to a low dose (2.8 Gy, 1 Gy/min) of whole-body IR after 5 days of treatment with GAA (15 mg/kg·bw) or vehicle by gavage, followed by the oral administration of GAA, DQ (5 + 50 mg/kg·bw), or vehicle. b Body weight monitoring of IR mice. c Representative images of H&E staining in spleen and testis at the experiment endpoint (n = 4 mice). d Gross organs stained with SA-β-Gal. e Immunohistochemical image and quantification of γH2AX expression in heart, liver, kidney, and lung (n = 4 mice). f ELISA to test the levels of serum klotho (aging-related protein) and g IL-6 (a cytokine of SASP) (n = 10 mice). h Representative images of pathological detection in the heart, liver, kidney, and lung (n = 4 mice). i Biochemical analysis of CKMB, j creatinine, k AST, and l ALT (n = 8 or 10 mice). m Behavioral performance of physical function including forelimb grip and n rotarod testing (n = 8 or 10 mice). Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Next, we evaluated the effectiveness of these antiaging strategies in targeting cellular senescence. They reduced the accumulation of SA-β-Gal in multiple tissues or organs (heart, kidney, liver, lung, adipose, and testis), the expression of γH2AX and p16INK4a (heart, kidney, liver, and lung), and the levels of circulating IL-6 in IR mice (Fig. 4d–g and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Comparatively, GAA was better at minimizing senescent cell burden in the heart and liver, while DQ was in the lung.

Consistent with the improvement of cellular senescence, GAA and DQ also alleviated pathological symptoms in multiple organs (Fig. 4h). However, biochemical analyses found that some IR mice treated with DQ exhibited signs of kidney dysfunction, evidenced by elevated creatinine levels, and liver damage, indicated by increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, in contrast to IR mice administered with the vehicle (Fig. 4i–l). GAA-treated IR mice did not suffer obvious toxic effects and showed reduced levels of CKMB, creatinine, and AST compared to untreated IR mice (Fig. 4i–l). Besides, GAA treatment increased insulin and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in IR mice, but DQ had no obvious effect on the metabolism disorder in these animals (Supplementary Fig. 3d–i). Further, both treatments significantly improved the compromised exercise capacity and muscle strength in IR mice, as measured by rotarod and grip strength (Fig. 4m, n and Supplementary Fig. 3c). These findings indicated both GAA and DQ played a powerful role in reducing senescent cells, while the administration of high frequencies of DQ could potentially lead to adverse effects.

GAA treatment increases the healthspan of aged mice

Our subsequent objective was to confirm the effects of GAA treatment on healthspan in natural aged mice. Mice aged 16 months, transiting towards old age, were administered a diet supplemented with GAA for 6 months (Fig. 5a). Survival analyses showed that GAA-treated mice had a slightly higher survival rate than the untreated elderly mice over 6 months (Fig. 5b). Notably, GAA-treated mice exhibited an extended life expectancy about 13 days when compared to vehicle-treated mice at 24 months of age, equivalent to a human gaining more than 1 year of life expectancy at 69 years of age (Fig. 5c). Compared to lifespan, we were more concerned with the healthspan of mice when they were alive. Thus, we applied measurements based on a clinically relevant frailty index, which consists of multiple age-related phenotypes, to assess the healthspan. A baseline health assessment was recorded at the start of treatment, and the total frailty score for each mouse was calculated every 2 months. We plotted the mean frailty score within every quantile of the current max lifespan of mice. Our results showed that GAA treatment decreased the incidence of frailty and postponed the severity, as evidenced by a 20% reduction in the area under the frailty curve when compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5d). Moreover, the mixed model analyses showed that GAA treatment significantly improved the frailty of aged mice (P < 0.001) and there was an interaction with mice age (P = 0.009) (Fig. 5e). These findings suggested that GAA improved the condition of elderly mice, making them less susceptible to negative health outcomes, akin to postponing the onset of illness.

Fig. 5. GAA treatment extends the healthspan of aged mice.

a Experimental design for 16-month-old male C57BL/6J mice fed with a GAA-added diet (120 mg/kg, n = 40 mice) and vehicle (n = 46 mice) for 6 months. b Survival curve of mice from 16 months to 22 months of age. c Life expectancy estimation in GAA-treated aged mice and their counterparts. Days of life gained in aged mice with GAA treatment compared to the controls. d The mean frailty index of mice treated with GAA and their counterparts. Mice exhibited various aging disorders and a higher risk of multiple morbidities when they approached the end of life (higher percentage of lifespan). The lifespan of the mice was divided into five quantiles (Q), and the frailty score of mice in each quantile of lifespan was calculated. Hence, this graph of the area under the curve may indicate whether the intervention can delay the onset of morbidity. e Monitoring of the frailty index for each mouse every two months. Mixed models to analyze repeated measurements of longitudinal data. Each dot represented the total score of one animal. f Gross organs and tissues stained with SA-β-Gal. g Immunoblots and densitometric analysis of the protein levels of senescent markers, including p53, p21, and p16 (n = 3 mice). h Assessment of serum klotho and i IL-6 levels by ELISA (n = 10 mice). j–l Indicators related to organ function (CKMB, creatinine, and ALT) (n = 10 mice). m, n Representative images in pathological analysis of heart, kidney, liver, and lung (n = 3 mice). Young: Young+vehicle; Old: Old+vehicle. Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Similar to the above observations, GAA-treated mice had lower levels of SA-β-Gal in various tissues or organs compared to GAA-deficient mice (Fig. 5f). GAA treatment also suppressed the expression of senescence-related proteins (p53, p21, and p16INK4a) in the heart, liver, kidney, and lung, increased circulating levels of aging-related protein (klotho) by 37%, and decreased the cytokines of SASP (IL-6) by 52% in aged mice (Fig. 5g–i). More importantly, aged mice manifested a body dysfunction, shown as markedly elevated CKMB, creatinine, and ALT. Remarkably, this dysfunction was largely mitigated by the treatment of GAA (Fig. 5j–l). Pathological analyses showed that the organs of aged mice appeared in myocardial disarray with necrosis, atrophy of renal tubules and shedding of epithelial cells, disrupted liver lobular structure, thickened alveolar walls, inflammatory infiltration, and fibrosis. By contrast, GAA treatment provided substantial benefits for restoring these abnormalities (Fig. 5m, n).

To verify whether GAA affected the healthspan of female mice, as it does in male mice, we also analyzed the physiological condition of aged female mice after 6 months of intervention with GAA (Supplementary Fig. 4a). As expected, senescence-related markers were significantly suppressed in multiple organs (Supplementary Fig. 4b–e). GAA treatment improved the adverse outcomes in inflammation, metabolism, and aging (Supplementary Fig. 4f–j). In terms of organ damage, GAA showed powerful advantages for the heart, kidney, liver, and lung, as manifested by improvements in biochemical markers and pathological changes (Supplementary Fig. 4k–o).

GAA treatment alleviates physical, metabolic, and brain-related dysfunction in aged mice

We then assessed the impact of GAA treatments on the physical parameters of aged mice. Behavioral detection showed that GAA-fed mice exhibited an approximate 70% increase in maximal running distance on the treadmill, a nearly 47% improvement in hanging time on the rotarod, and an ~30% enhancement in grip strength compared with controls (Fig. 6a–c). Nuclear magnetic resonance analysis further determined that the GAA-treated mice maintained more muscle mass (Fig. 6d), which was consistent with the performance of muscle/body index and histomorphology analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5a, c). Bone structure analysis through microcomputed tomography (microCT) showed that GAA treatment increased bone mass (bone volume divided by total volume percentage) and the number and thickness of bone trabeculae in the femur compared with that in controls (Fig. 6e). GAA treatment also maintained the length of the femur and tibia (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The knee cartilage in aged mice was uneven and partially lost, which was reversed by GAA treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5d).

Fig. 6. GAA treatment improves physical, metabolic, and brain-related dysfunction in aged mice.

a Measurement of time in rotarod, b running distance on the treadmill, and c grip strength of experimental mice (n = 8 mice). d Body composition analysis in lean mass of mice by nuclear magnetic resonance (n = 12 mice). e Representative microCT images of bone microarchitecture at the femur. Quantification of microCT-derived bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) (n = 6 mice). f–h The path map during the behavioral experiment. Comparative statistics including the f times entered into and time spent in the open arms in elevated plus maze testing, g the distance and the frequencies of access to the central zone in open field testing, h the time interacting with the novel objects in novel object recognition testing (n = 10 or 12 mice). i–k Biochemical index of lipid metabolism, including TG, FFA, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C (n = 10 or 15 mice). l The weight distribution of the aged mice in each group at the end of the experiment. m Glucose tolerance test and area under the curve of mice (n = 8 mice). n Insulin levels and the corresponding o insulin resistance index (n = 10 mice). Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

It is common for aging to bring about changes in mental state, such as an increase in feelings of anxiety and a decrease in the desire to explore. We thus assessed depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors and cognitive function in aged mice after GAA treatment or deficiency. GAA-treated mice exhibited less spontaneous anxiety-like behavior compared with controls, determined by the entering time into the open arms of the elevated plus maze (Fig. 6f). In the open field testing, GAA-treated mice showed less depression-like behavior and more exploratory behavior compared to those treated with a vehicle (Fig. 6g). The novel object testing revealed that GAA treatment increased the time that aged mice spent interacting with the novel object (Fig. 6h).

We next sought to evaluate how GAA treatment affected metabolic homeostasis in elderly mice. Interestingly, we noticed substantial reductions in serum triglycerides (TG), free fatty acids (FFA), and total cholesterol (TC) levels in aged mice when compared to their younger counterparts (Fig. 6i–k). This suggested that the aging process led to a decline in the ability of lipid metabolism. The decrease in TC was attributed to the reduction in HDL-C (Fig. 6k). Compared to pre-aging mice, the majority of aged mice experienced gradual weight loss, which became more severe as they approached the end of their lifespan (Supplementary Fig. 5e). This was consistent with the observations during our experiments that significant weight loss may serve as a precursor to mortality in mice. Conversely, GAA slowed the pace of weight reduction in aged mice, despite no significant alteration in their food intake (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f). Furthermore, we uncovered that aged mice treated with the vehicle experienced weight loss, with 69% of them dropping below the average weight (28.3 g) of the entire aged mice population, which encompasses both the Old group and the Old+GAA group. In contrast, only 40% of the GAA-treated mice were below this average (Fig. 6l). Body composition analysis also indicated that GAA treatment maintained the total fat mass in aged mice (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Not only that, GAA-treated mice exhibited a more favorable fat distribution pattern, characterized by increased subcutaneous fat and decreased gonadal fat distribution, compared to those treated with the vehicle (Supplementary Fig. 5h). Glucose homeostasis was deemed to play a dominant role in regulating metabolic health during aging. GAA-treated mice had lower concentrations of fasting blood glucose and metabolized glucose more efficiently than the control mice (Fig. 6m). Likewise, improvements in insulin resistance were observed in aged mice after treatment with GAA (Fig. 6n, o).

GAA administration prevents aging-related phenotype in obese mice fed with the western diet

Apart from aging, we wanted to investigate whether GAA conferred any benefits toward age-related diseases. Diet-induced obesity serves as the foundation for various age-related diseases24,25. Therefore, we explored whether GAA conferred a protective effect in obese mice. For this purpose, we established a mice model by providing a western diet (WD, 42% fat) for 16 weeks, followed by a 12-week intervention with GAA via intraperitoneal injection, ensuring a bioavailability of the natural products (Fig. 7a). As expected, the body weight of WD-fed mice was increased in comparison to controls fed with a normal diet (ND, 11% fat). With the treatment of GAA, the weight of obese mice slowly decreased (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7. GAA treatment improves aging-related phenotype in obese mice.

a Schematic design for 2-month-old C57BL/6J mice fed with a western diet or normal diet for 16 weeks, and then given a treatment with GAA for 12 weeks. b Mean body weight monitoring in obese and control mice and the statistics of final body weight (n = 10 mice). c Representative images and quantification of tissues stained with SA-β-Gal, including heart, kidney, liver, and lung. The statistical data were expressed as the ratio of positive stained area (n = 3 mice). d The circulating klotho and e IL-6 levels were determined by ELISA (n = 7–10 mice). f Measurements of organ function of the heart (CKMB), g kidney (creatinine), and h, i liver (ALT and AST) (n = 8 or 10 mice). j Masson staining to assess the fibrosis in organs (n = 4 mice). k Physical function testing in the time spent on rotarod and l forelimb grip (n = 10 mice). m Representative microCT images and quantification of bone volume fraction, trabecular number, trabecular thickness, and trabecular separation (n = 5 mice). n Sectional images of H&E staining and area quantification in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) and inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT). Oil red staining and quantification of the liver (n = 4 mice). o Glucose tolerance test analysis and quantification by area under the curve (n = 8 mice). p Assessment of insulin levels and q insulin resistance index (n = 8 or 10 mice). Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Moreover, we found that senescent cells not only existed in the liver and adipose tissue, but also accumulated in the heart, kidney, and lung of WD-fed mice (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Aging-related protein (klotho) and SASP cytokine (IL-6) were abnormally expressed in WD-fed mice compared to ND-fed mice (Fig. 7d, e). Conversely, the GAA administration restrained these senescent performances. Accompanied by the occurrence of cellular senescence, the organs of obese mice also became dysfunctional, showing elevated levels of CKMB, creatinine, ALT, AST, and pathological damage (Fig. 7f–i and Supplementary Fig. 6b). GAA administration protected these organs against disorder, with a particular emphasis on decreasing fibrosis levels (Fig. 7j).

We further ascertained the improvement effects of GAA intervention on the physical abilities of obese mice. For behavioral analysis, WD-fed mice exhibited a reduction in grip strength and the duration of their performance on the rotarod, compared with ND-fed mice. Conversely, obese mice that received GAA experienced prevention of such physical dysfunctions. (Fig. 7k, l). Gastrocnemius muscle area was also increased in GAA-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c–e). In the microCT imaging, GAA treatment significantly improved bone mass and trabecular separation compared to WD-fed mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 7m). We next explored the role of GAA treatment in the metabolic homeostasis of WD-fed mice. Treatment with GAA led to a profound decrease in both the size and mass of adipose tissue, as well as the hepatic fat deposits in obese mice (Fig. 7n and Supplementary Fig. 6f). A series of biochemical analyses also confirmed the beneficial effects of GAA treatment on lipid metabolism in obese mice, including decreasing TG, FFA, TC, and LDL-C (Supplementary Fig. 6g–k). Remarkably, the ability of glucose metabolism in obese mice treated with GAA approached that of mice fed with ND. Different from WD-fed mice treated with vehicle, GAA-treated mice exhibited notable reductions in fasting blood glucose and insulin, as well as improved rate of glucose metabolism and insulin resistance (Fig. 7o–q).

GAA prevents cellular senescence by maintaining ribosome homeostasis

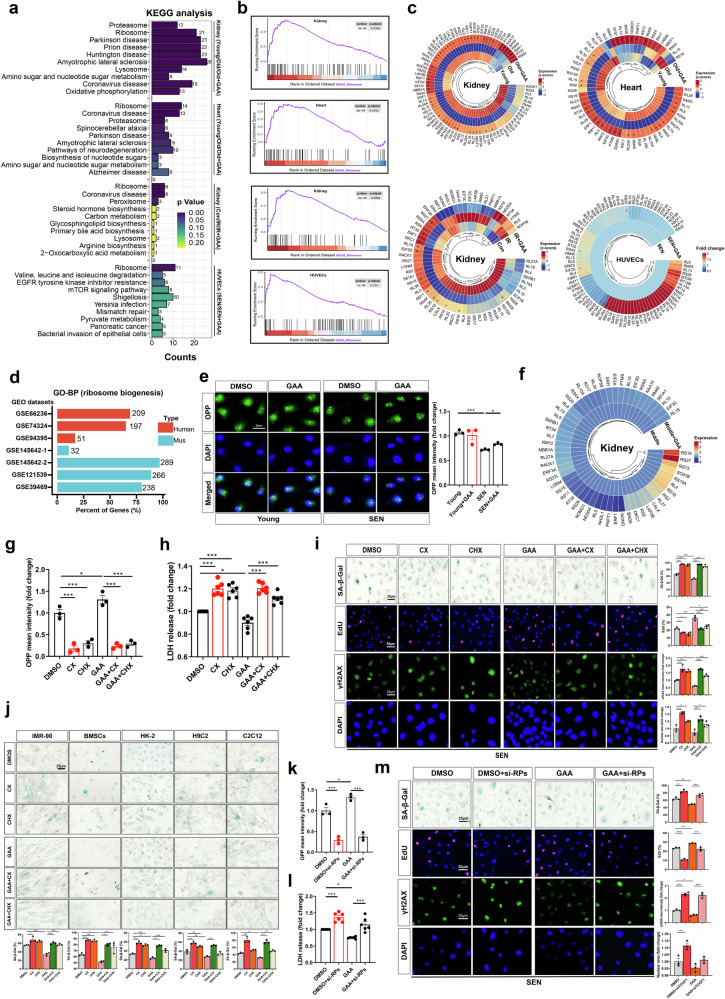

To explore the potential mechanisms by which GAA modulated cellular senescence to increase healthspan, we performed proteomic analyses in aging mice. We first examined the protein profiles of the heart and kidneys, the organs in which GAA reversed aging noticeably. Bioinformatics in the kidney showed that compared with the old group, there were 774 different proteins in the young group, 704 in the GAA-treated group, and 464 were shared in both groups (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Within the heart, 100 distinct proteins were commonly changed (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Further, enrichment analyses were conducted on the distinct proteins of each of the two groups. KEGG analyses showed that ribosome and proteasome pathways were the top and significant alterations in both the kidney and heart (Supplementary Fig. 7b, e). Consistent observations were also evident in the analyses of shared distinctive proteins (Fig. 8a). Likewise, GO analysis identified numerous regulation pathways related to ribosome and proteasome, especially the substantial changes of the ribosome in cell components (Supplementary Fig. 7c, f). We then validated the effect of GAA on the ribosome pathway in the kidneys of premature aging mice. Although control mice and GAA-treated IR mice shared only 30 different proteins in comparison to those in the IR mice, the enrichment analysis also revealed significant regulation in the ribosome pathway (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Fig. 7g–i). At the cellular level, enrichment analysis showed ribosome was the top pathway changed by GAA treatment in senescent HUVECs (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Consistently, ribosome biogenesis was significantly changed in many other senescent cell models (Fig. 8d). Noticeably, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) profiling demonstrated that GAA significantly upregulated the ribosomal pathway in the kidneys and heart of aged mice, as well as the kidneys of IR mice and senescent HUVECs (Fig. 8b). These observations were in line with the protein profiles associated with ribosomal function (Fig. 8c). Further, we evaluated ribosome function by O‐propargyl puromycin (OPP) incorporation. Compared to younger cells, senescent HUVECs have a decreased ability to translation function, which was improved by GAA treatment (Fig. 8e). GAA also improved the ribosomal function in aging nematode (Supplementary Fig. 8d). Evidently, GAA had a negligible impact on ribosome function in young cells, cancer cells, and young kidneys (Fig. 8e, f and Supplementary Fig. 8e). Overall, the ribosome pathway exhibited a decline in aging status, whereas GAA has the ability to restore this dysregulation.

Fig. 8. GAA alleviates cellular senescence partially mediated by improving ribosome dysfunction.

a KEGG and b GSEA analyses of differential proteins (P < 0.05, fold change >1.5) in the kidney and heart of natural aging model, kidney in IR-induced premature aging model, and natural senescent HUVECs (n = 5 independent experiments). c Heatmaps depicting all detectable proteins of ribosome pathway in the above aging-related models. *GAA treatment significantly regulated the protein compared to the counterparts, with P < 0.05. d Biological processes in GO analysis for differential mRNAs between senescent cells and non-senescent cells. Data were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. e Representative images of the O‐propargyl puromycin (OPP, 10 μM) incorporation experiment in young and senescent HUVECs with GAA treatment or not (n = 3 independent experiments). Fluorescence intensity of OPP to measure ribosomal translation function. f Heatmap of detectable proteins related to ribosome pathway in the kidney of middle-aged mice treated with GAA or vehicle. g Fluorescence intensity of OPP in HUVECs when exposed to CX-5461 (CX, 125 nM) or cycloheximide (CHX, 125 nM) for 5 days and intervened with GAA ion (10 μM) (n = 3 independent experiments). h, i Representative images and quantification of senescence-related markers, including the levels of LDH release, SA-β-Gal, EdU, γH2AX, and nuclear area (n = 3 or 6 independent experiments). j SA-β-Gal staining of cells exposed to CX and CHX with the treatment of GAA. Cells included IMR-90, BMSCs, HK-2, H9C2, and C2C12, and the exposure and intervention time were 3 days, 3 days, 10 days, 6 days, and 5 days, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). k Fluorescence intensity of OPP in HUVECs after silencing the RPL7 and RPL32 by siRNA and treated by GAA (10 μM) (n = 3 independent experiments). l, m Representative images and quantification of senescence-related markers, including the levels of LDH release, SA-β-Gal, EdU, γH2AX, and nuclear area (n = 3 or 6 independent experiments). Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Next, we investigated all the above proteomics results and noticed that GAA mainly changed ribosomal proteins and upstream mechanisms, such as ribosome biogenesis, but also partially altered downstream translation-related factors (Supplementary Fig. 8f). We thus selected two inhibitors, CX-5461 (CX), which is intended to suppress RNA polymerase I-driven rRNA transcription, and cycloheximide (CHX), which is designed to impede the elongation phase of eukaryotic translation. In young HUVECs, both inhibitors (24 h, 250 nM) significantly induced senescence, indicating ribosome dysfunction functioned as an upstream stimulus to cause cellular senescence. GAA treatment, in turn, partially relieved the cellular senescence induced by these two inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 8h–k). OPP incorporation experiments also supported that the ribosome function of young cells was not completely lost under short-term stimulation by these inhibitors, which was repaired by GAA (Supplementary Fig. 8g).

Furthermore, we analyzed the mediation of ribosome function in the effects of GAA on senescent cells. After HUVECs were exposed to these inhibitors for 5 days, the ribosomal translation function of the cells was reduced by 70–80% compared to DMSO controls. Unlike in young cells, the administration of GAA did not succeed in reversing the substantial decline in ribosome function observed in senescent cells (Fig. 8g and Supplementary Fig. 8l). Moreover, the disturbance of ribosome function repressed the improvement effect of GAA on cellular senescence, particularly the exposure to CX (Fig. 8h, i). Similar results have been observed in other natural senescent cells, including IMR-90, BMSCs, HK-2, H9C2, and C2C12 (Fig. 8j). Subsequently, we conducted experiments to determine if the endogenous impairment of ribosome function yielded comparable outcomes. Following the disruption of two ribosomal proteins (RPL7 and RPL32) by siRNA, we observed an exacerbation of the senescent phenotype in HUVECs (Fig. 8l, m). In addition, the suppression of ribosomal protein not only diminished the cell’s ribosomal function but also impeded the efficacy of GAA in delaying the senescence of HUVECs (Fig. 8k–m and Supplementary Fig. 8m). In summary, GAA effectively mitigated cellular senescence by modulating ribosome homeostasis.

Identification of TCOF1 as a direct binding protein for GAA

To further investigate the molecular target by which GAA prevents cell senescence, we screened for potential GAA-binding proteins by a HuProt™ 20 K human protein microarray. After incubating the array with either Bio-GAA or free biotin, the detection was performed using Cy5-Streptavidin (Fig. 9a). We calculated the fluorescence intensity (IMean) for each site and identified 345 proteins with an IMean ratio (Bio-GAA to biotin fluorescence signal ratio) greater than 1.4. Among these, Treacle ribosome biogenesis factor 1 (TCOF1) stood out due to its close association with ribosome homeostasis26,27, displaying the IMean ratio of 1.91 (Fig. 9b). Molecular docking analysis further supported this finding, revealing binding energy of -5.8 kcal/mol for the interaction between GAA and TCOF1 (Fig. 9c). In addition, cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) in senescent HUVECs demonstrated that GAA significantly protected TCOF1 from temperature-induced denaturation, indicating a direct interaction (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 9. Identification of TCOF1 as a direct binding protein for GAA.

a Schematic steps for identifying GAA-binding proteins using microarrays fabricated with recombinant human proteins. b Magnified image of HuProtTM and Bio-Celastrol binding to GAA spot on the protein array. c Computational docking and molecular simulation. d GAA promoted TCOF1 resistance to different temperature gradients by cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) analysis in senescent HUVECs (n = 3 independent experiments). e Fluorescence intensity of OPP in HUVECs after silencing the TCOF1 by siRNA and treated by GAA (10 μM) (n = 3 independent experiments). f, g Representative images and quantification of senescence-related markers, including the levels of LDH release, SA-β-Gal, EdU, γH2AX, and nuclear area (n = 3 or 6 independent experiments). h The expression level of TCOF1 analyzed by proteomics (n = 6 independent experiments). i, j Phosphorylation detection of TCOF1 in HUVECs (Phos-assay) and aging kidney (LC-MS/MS analysis) (n = 3 independent experiments or mice). k GAA promoted TCOF1 resistance to proteases and phosphatase by drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) analysis in senescent HUVECs (n = 3 independent experiments). l Mechanism diagram. GAA interacts with TCOF1, preventing its dephosphorylation induced by phosphatase. This interaction stabilizes pTCOF1, which in turn supports RPs production. Accordingly, GAA ensures proper ribosome biogenesis and subsequent ribosomal function, thereby preventing cellular senescence potentially by alleviating the DNA damage response (DDR), modulating the p53/p21 pathway, and ZAKα kinase activity. Dashed lines indicate previous reports. Comparisons are performed by Two-sided t tests or one-way ANOVA analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data and exact P value are provided as a Source data file.

Furthermore, the knockdown of TCOF1 exacerbated ribosomal dysfunction in senescent HUVECs, resulting in a reduction of OPP fluorescence intensity by approximately 90%. Notably, GAA was incapable of reversing this significant decline in ribosome function (Fig. 9e). Inhibition of TCOF1 also diminished the anti-senescence effects of GAA, suggesting that GAA’s function was mediated by TCOF1 (Fig. 9f, g). However, the proteomic results showed that GAA did not significantly alter TCOF1 expression level in senescent HUVECs (Fig. 9h). Notably, TCOF1 contains multiple phosphorylation sites, which are known to be functionally significant28. We observed that the phosphorylation levels of TCOF1 decreased in senescent HUVECs, but they were restored following GAA treatment. This pattern was consistent with observations in the kidneys of naturally aging mice (Fig. 9i, j). Given that small molecule binding can alter protein conformation29, we further analyze the stability of GAA-TCOF1 complex. Drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) assay in senescent HUVECs showed that GAA inhibited TCOF1 and pTCOF1 degradation induced by pronase and protein phosphatase (Fig. 9k). Overall, GAA interacts with TCOF1, preventing its dephosphorylation induced by phosphatase. This interaction stabilizes pTCOF1, which in turn supports ribosomal proteins (RPs) production. Accordingly, GAA ensures proper ribosome biogenesis and subsequent ribosomal function, thereby preventing cellular senescence (Fig. 9l).

Discussion

Through high-content screening, we discovered that GAA exhibited a wide range of efficacy in combating cellular senescence, and was concurrently deemed safe for application. Our data further confirmed that GAA treatment was capable of preventing aging and extending healthspan in multiple species. GAA conferred powerful benefits in protecting against aging-related physical dysfunction and metabolic imbalance. Importantly, GAA intervention did not cause organ damage or excessive proliferation in both young mice and tumor-bearing mice. For the underlying mechanism, GAA targeted TCOF1 to maintain ribosome homeostasis and accordingly alleviated cellular senescence across multiple models.

Cellular senescence is increasingly recognized as the leading contributor to age-related disorders30. Before our study, researchers have developed a handful of screening platforms to identify compounds with the properties for preventing senescence. Specifically, these platforms usually measure cellular senescence by cell number or SA-β-Gal expression and conduct screenings within the compound libraries of single targets, such as kinase inhibitors or autophagy regulators31–33. Drawing from previous experiences, our study established a high-content imaging-based screening platform with optimized evaluation metrics that capture multiple senescence markers, thereby providing a more comprehensive view of cellular senescence processes. Our platform’s versatility was enhanced by incorporating diverse cell types and senescent models induced by replication stress, oxidative stress, and genotoxic agents. This multi-dimensional approach allows for the identification of compounds with broad-spectrum anti-senescent effects. Additionally, by expanding the range of compound dosages, the platform enables a thorough analysis of dose-dependent responses and toxicity thresholds, which are essential for preclinical assessments of antiaging agents. Thus, it provides a relatively efficient and scalable tool for advancing natural product discovery in aging research.

Recently, GAA was reported to improve Alzheimer’s disease via the Th17–Tregs axis, regulate lipid metabolism in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver, and inhibit inflammation in mice with pulmonary fibrosis34–36. A single study examined the relationship between GAA and cellular senescence in Aβ25-35-stimulated mice hippocampal neuronal cell line, which was designed to mimic the characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease37. Overall, the effect of GAA on cellular senescence remains inconclusive. Our study was groundbreaking in verifying the geroprotective role of GAA in multiple models. In vitro, GAA had the potential to inhibit cellular senescence across various cell types. In comparison to the classical antiaging molecule rapamycin, GAA was superior against cellular senescence and had a rivaled effect on the healthspan of nematodes. Also, both GAA and DQ could reduce the accumulation of senescent cells and improve organ disorders and physical dysfunction in IR-induced premature aging mice19. Moreover, we focused on the improvements of GAA in the fundamental features of the aging process, especially physical and metabolic dysfunction. GAA treatment boosted motor capacity and decreased lipid deposition in aging C. elegans. In natural aging and obese mice, GAA prevented muscle and bone trabecular loss and enhanced physical function. Interestingly, GAA functioned on glucose and lipid metabolism and maintained body weight in premature and natural aging mice, but reduced fat accumulation in obese mice. This discovery emphasized the capacity of GAA to regulate metabolic flexibility and thus adapt to conditional changes in metabolic demand38. The aforementioned studies provided substantial evidence supporting the antiaging properties of GAA, ranging from cellular levels to entire organisms.

In addition to the efficacy, GAA possessed the advantages of low toxicity and favorable drug properties. During our in vitro observations, GAA did not cause any notable harm to cells even at a concentration of 1000 μM. In contrast, compounds of flavonoids, such as S4239, S4782, and S9111, resulted in considerable cell death when used just at 100 μM. Consistently, studies showed that supplements with high concentrations of flavonoids reduced enzyme activity and thereby caused disorders of the body18. Our investigations further excluded GAA-incurred cellular damage by the verification among 10 normal cells. Long-term GAA treatment also had no obvious adverse effects on middle-aged and elderly mice. As an anti-senescent molecule aimed at prevention, GAA has the potential to affect the cell cycle, which necessitated consideration of whether such drugs may disrupt the proliferative state of other cells. Our study found no indication of heightened proliferation in normal somatic cells or cancer cells when treated with GAA. Indeed, GAA could inhibit tumor proliferation and cancer cell migration, corroborating earlier reports on its anti-tumor effects39,40. By contrast, some senotherapeutics always exhibited side effects. Typical adverse responses of rapamycin include anemia, thrombocytopenia, peripheral edema, nausea, and diarrhea, whereas metformin may result in gastrointestinal adverse reactions and lactic acidosis41,42. For the senolytics, ABT-263 was frequently reported to cause thrombocytopenia and destroy hemostatic function, and DQ had hematological, gastrointestinal, and respiratory side effects43,44. Of concern, we found that DQ treatment caused mild testicular damage as well as liver and kidney dysfunction in some premature aging mice. Based on the aforementioned findings, GAA may be a promising antiaging molecule with promising clinical applicability. Although no adverse effects were observed in our animal models, further studies are needed to evaluate the potential long-term toxicities or side effects of GAA.

Similar to numerous natural products, the mechanism of action of GAA appears complex and requires exploration. The aggregate of protein profiles in different mice organs consistently revealed the changes in ribosome-related pathways in aging models. Our data further showed that both inhibition of ribosome biogenesis and translation triggered young cells to senescence, indicating ribosomal dysfunction was a driver of cellular senescence. Similarly, Pantazi et al. described that inhibition of 60S ribosomal biogenesis led to cellular senescence45. Regarding the underlying mechanism, cell cycle regulators under the surveillance of ribosome biogenesis, ribotoxic stress-activated ZAKα kinase, and autophagy-mediated degradation of ribosomes were involved in the regulation of cellular senescence46–49. Conclusively, defects in ribosomes can cause cellular senescence through various molecular pathways.

Furthermore, we discovered that GAA can directly bind to TCOF1, a protein that is heavily phosphorylated and plays a role in the process of ribosome biogenesis28,50. When TCOF1 is knocked out, GAA failed to maintain ribosome function and mitigate cell senescence. Although TCOF1 expression levels were not increased following GAA treatment, the protein’s conformation may change, enhancing its thermal stability and resistance to proteolysis, similar to the reported function of other natural products29,51. Notably, TCOF1-governed regulation of ribosome modifications and global translation programs is largely dependent on phosphorylation30. Building on this understanding, we found that GAA treatment led to a significant increase in TCOF1 phosphorylation levels in senescent HUVECs, likely attributed to the resistance of the GAA-TCOF1 complex to phosphatases. In the context of obesity, targeting senescent cells in obese mice has been shown to alleviate obesity-related disorders, such as lipid accumulation and insulin resistance. Alongside our findings that GAA regulated ribosomal homeostasis across multiple senescent cell types, we further speculate that GAA improves cellular senescence and thereby mitigates obesity through the TCOF1-ribosomal homeostasis pathway. Overall, GAA may prevent cell senescence by targeting TCOF1 to maintain ribosomal homeostasis and further research will be necessary to fully understand whether and how TCOF1 contributes to GAA’s effects on obesity.

Altogether, we performed high-content screening and identified GAA as a promising senotherapeutic strategy for preventing cellular senescence and extending healthspan. Derived from natural sources with pronounced efficacy and hypotoxicity, GAA exerted an anti-senescent role by targeting TCOF1 to maintain ribosome function. These findings may present opportunities for the prevention of morbidity during the aging process. Further translational and clinical trials are warranted to achieve the overall aim of a longer and healthier life.

Methods

High-content screening

The natural product library included 805 compounds from the Selleck-L1400. Each well of plates holds 30 μl of 10 mM compounds in DMSO solution. When the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells was about 10–20%, it can be considered that cells were initially senescent, and the SA-β-Gal+ cells were increased to more than 50% in the following culture (Supplementary Fig 1a). Senescent cells were further characterized by assessing their proliferative capacity, morphology, and extent of damage. Cells under initial senescence were grown in black 96-well plates (PerkinElmer 6005182, USA) for the chemical screen. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 805 compounds at a concentration of 10 μM. DMSO treatment was set as a control group in every plate. After an additional 3 days of incubation, cells were fixed, stained with SA-β-Gal and DAPI, and then analyzed in a high-content imaging system (PerkinElmer Operetta CLS™, USA). The instrument automatically scanned (100×) and captured a total of 45 regions of cell images throughout each well on the plate. The obtained cellular images were further analyzed to assess senescent phenotypes across multiple dimensions, including the number of nuclei, nucleus area, cell area, the ratio of cell width to length, and the proportion of SA-β-Gal+ cells (Fig. 1a). Compounds that meet the following criteria were included in the second round of screening: increase cell count, decrease nuclear and cell area, decrease cell ratio of width to length, and decrease SA-β-Gal+ cells by 30% (Supplementary Table 1).

Senescent models of HUVECs, induced by replication, H2O2, etoposide, and the above-mixed stimulus, were used in the second screening. By measuring cell number, nuclear area, LDH release levels, and the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells after the intervention, candidate compounds were selected in the third screening.

Finally, we established replication-induced senescent models of MEF cells and L02 cells. Both initial senescent cells were treated with different concentrations of compounds (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 500, and 1000 μM), and 1 optimal compound was picked according to the expression of the number of SA-β-Gal+ cells and the release of LDH at each dose.

Cell culture and senescence induction

Human IMR-90 fibroblasts and HUVECs were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, China). Primary MEFs were isolated from mouse embryos as previously described52. Cells were maintained in culture medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco, USA) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C, and 5% CO2. Cells were serially passaged at a 1:2 dilution. Low-passage cells were considered young cells with population doublings times less than 2 days and SA-β-Gal+ cells less than 5%. Senescent cells were determined when SA-β-Gal+ cells were greater than 20% and the cell size was significantly increased. For replication-induced senescence, cells were continuously passaged and cultured for sufficient time until they became senescent. For etoposide-induced or H2O2-induced senescence, young HUVECs were exposed to 500 nM etoposide or 125 μM H2O2 for 4 h and then cultured in a fresh medium for 3 days. For mixed stimulus-induced senescence, young HUVECs were incubated in a medium with 500 nM etoposide and 125 μM H2O2 for 4 h and then cultured in fresh medium for 6 days. Following a 24 or 48 h period post cell seeding, the interventions were introduced. Thereafter, the cell medium and interventions were refreshed every 48 h until the end of the experiment. More detailed information on sources, culture conditions, senescence induction, and interventions of all cells are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal)

Tissues were collected from euthanized mice after cardiac perfusion with saline to flush the blood clean. A piece of tissue without blood was directly immersed in the SA-β-Gal dye according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime, China). Samples were incubated for 8–48 h at 37 °C depending on the SA-β-Gal content. For the frozen tissue sections and cells, they were collected and fixed for 5 min at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, samples were incubated with a detection solution at 37 °C for 12–14 h. Once dried, samples were examined under a bright-field microscope (Mshot, China). The relative SA-β-Gal+ area was quantified using Image J software (NIH), calculated by dividing the SA-β-Gal+ area by the total area. The sample size was a minimum of 3.

Cell damage assessment

The ratio of LDH release to assess cell damage. Two hours before the end of the experiment, half of the supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C, and then the LDH-releasing solution was added to the wells. The remaining supernatant was collected after 1-h incubation. Supernatants were centrifuged and then incubated with the LDH test solution (Beyotime, China) at 37 °C for 15–30 min. Absorbance was measured on an enzyme-labeler (Thermo Scientific, USA), and the ratio of absorbance of the previous supernatant to the last supernatant was calculated to measure the LDH release.

ADMET analyses

ADMETlab2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) was used for the analysis of the predicted ADMET properties of hit compounds53. Physicochemical properties and potential toxicity predictions are output from the website database. We estimated the physicochemical properties of GAA according to the Lipinski rules54: molecular weight <500; the logarithm of the n-octanol/water distribution coefficient ≤5; number of hydrogen bond acceptors ≤10; number of hydrogen bond donors ≤5; topological polar surface area <140. Compounds are predicted to be poor absorption or permeation when they disobey the above more than 1 rule. Toxicity predictions include the human ether-a-go-go related gene, human hepatotoxicity, drug-induced liver injury, the Ames test for mutagenicity, rat oral acute toxicity, maximum recommended daily dose, skin sensitization, carcinogenicity, eye corrosion, eye irritation, and respiratory toxicity.

Cell proliferation

The proportion of EdU+ cells was used to measure the level of cell proliferation. Before the end of the experiment, cells were labeled with EdU (10 μM) for 2 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed, and cells were washed once with PBS. They were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5–10 min, followed by washing 3 times with PBS. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 and three subsequent washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with the EdU reaction buffer for 30 min at ambient temperature, shielded from light in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime, China). Following a PBS wash, cell nuclei were stained. Samples were examined under a fluorescent microscope (Mshot, China). The proportion of EdU+ cells was quantified using Image J software (NIH).

Colony formation assay

Carcinoma cells were seeded in a six-well cell culture plate. The GAA was introduced to the experimental groups, while DMSO was added to the control group. The medium and drugs were replaced every 2 days, and the cells were cultured continuously until many cell cluster were observed. After fixing the cells in the experimental and control groups with 4% paraformaldehyde, the cells in both were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime, China). Unbound dye was washed away ten times with PBS, and cells were allowed to air dry.

Scratch assay

Carcinoma cells were inoculated into a six-well culture plate and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then scratched with a wall, and the floating cells and debris were washed away with PBS. The scratch distance was photographed and recorded with a microscope. GAA with a concentration of 10 μM was added to the plate, and fresh medium with DMSO was used as the control group. After 48 h incubation, the floating cells were washed off, and the scratch distance was recorded by microscope.

Aging-related phenotypes analysis in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans)

N2 Bristol (wild-type) strain of C. elegans was provided by the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University and maintained at 20 °C. The strain was grown on Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) agar plates containing Escherichia coli OP50 bacterial lawn. Rapamycin or GAA was dissolved in OP50 solution to prepare suspensions of different concentrations (100 μM rapamycin; 10 μM, 100 μM, and 1000 μM GAA). A mixture consisting of bacteria and these interventions (80 μl) was then inoculated onto NGM plates. All experiments were conducted with L4 synchronized worms and were performed three times independently.

Lifespan analysis

Young adult worms (30 per plate) were grown on plates with tested compounds to score lifespan. Worms were transferred to new plates every day during their reproductive period. After reproduction ceased, worms were transferred every 3 days. The survival and death numbers of worms in each group were recorded every day until all worms died.

Heat stress resistance

After 7 days of intervention, the worms were transferred to an incubator at 30 °C, and observed under the microscope every 1 h until all the worms died.

Oxidative stress resistance

After 7 days of intervention, the worms were transferred to an NGM medium coated with 1.5% H2O2, cultured at 20 °C, and observed under the microscope every 1 h until all the worms died.

Others

After treatment for 10 days, worms were randomly selected to measure.

Lipofuscin measurement

Worms were anesthetized in a 25 mM levamisole buffer, and images were captured immediately by the fluorescence microscope at blue excitation light (405–490 nm) of DAPI.

Reactive oxygen (ROS) and lipid measurement

Worms were incubated DCFH-DA (10 μM, Beyotime, China) or Nile Red fluorescent probe (10 μg/ml, Sigma, USA) at 20 °C for 30 min. Then positive expressions were observed in fluorescence microscopy.

Physical function

Worms were observed the spontaneous or regular sinusoidal movement (Normal), irregular or uncoordinated movement (Sluggish), and movement only by touching (Immobile). Worms were detected in the swing frequency of head and tail and pharyngeal swallowing frequency within 1 min.

Animal studies

Eight-week-old male and female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River and housed in a specific pathogen-free environment at 22–25 °C with a reverse 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. Mice with ad libitum excess to water and food were randomly assigned to control or treatment groups. All animals were treated following the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health, and all animal procedures were approved by the Tongji Medical College Council on Animals Care Committee (IACUC Number: 3675). In addition, we employed varied administration routes—oral gavage, dietary incorporation, and intraperitoneal injection—across different mouse models to investigate the potential damage caused by different modes of GAA administration in mice. The mice models were described below:

Middle-aged mice (aged 5 months)

Mice aged 2 months were fed a standard diet or GAA-added standard diet (GAA diet, 120 mg/kg·diet) (Chengdu Pufei De Biotech Co., Ltd, China) for 3 months.

Tumor-bearing mice

For the subcutaneous tumor model, Hep1-6 liver cancer cells (5 × 106) were subcutaneously inoculated into the right inguinal fold regions of mice. After 1 week of feeding with a standard diet, mice were randomly assigned to groups according to mean tumor volume. GAA (15 mg/kg·bw) or vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% polyethylene glycol, and 50% PBS) was injected intraperitoneally once every 3 days for 18 days. The maximal allowable tumor size/burden (diameter less than 1.5 cm) was not exceeded.

IR-stimulated mice

After 5 days of continuous gavage with GAA (15 mg/kg·bw) or vehicle, mice were exposed to a low dose (2.8 Gy, 1 Gy/min) of whole-body IR by an X-ray irradiator (RS2000pro-225, Rad Source Technologies, USA) to induce in vivo cell senescence acutely. Three days later, mice were treated with GAA (15 mg/kg·bw), DQ (5 mg/kg·bw+50 mg/kg·bw) (Sigma, USA), or vehicle by oral gavage once every 3 days for 21 days.

Western diet-induced obesity in mice

Mice were fed a ND (21.5% protein, 11.1% fat, and 67.4% carbohydrates) or WD (14% protein, 42% fat, 44% carbohydrates, 0.2% cholesterol) (Nantong, TP 26304, China) with high-sugar water (23.1 g/l d-fructose and 18.9 g/l d-glucose) for 16 weeks. Mice were then randomly assigned to groups according to body weight. GAA (15 mg/kg·bw) or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally once every 3 days for 12 weeks.

Natural aging mice (aged 22 months)

Male and female mice aged 16 months were fed a standard diet or GAA diet (120 mg/kg·diet) for 6 months. All surviving mice were assessed for frailty index every 2 months. The product limit method of Kaplan and Meier was used to conduct the survival curve using GraphPad Prism. The proportional hazards survival analyses were performed to assess the effects of GAA treatment on life expectancy among mice (stpm2 command in Stata). Residual life expectancy was estimated as the area under the survival curve up to age 36 months (equivalent to a human age of 94 years). Days of life gained were calculated as the difference in status between the areas under two status survival curves.

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography

Serum and tissue GAA were extracted according to the procedure described by Teekachunhatean et al. with some modifications55. Briefly, 100 μl serum or 40–50 mg tissue sample was homogenized in 100 µl 2% hydrochloric acid solution, and 200 μl methanol was then added for deproteinization. To the mixture, 600 µl acetonitrile was added, and the sample was vortexed for 5 min followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 5 min at 12,000× g. The supernatant was collected and dried under a nitrogen stream. Then, the residue was reconstituted in 100 μl of the mobile phase, and a 5 μl aliquot of the resulting solution was injected into the UPLC coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS) system for analysis. A UPLC 30 A system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) coupled with a TripleTOF 6600 high-resolution mass spectrometer (Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada) was used for GAA analysis. A Kinetex C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm) (Phenomenex) was used to achieve metabolite separation. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and acetonitrile (B) with the following gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.40 ml/min: 0–2.5 min, 63% A; 2.5–2.75 min, 63-55% A; 2.75–3.75 min, 55% A; 3.75–4.0 min, 55-63% A; 4.0–7.0 min, 63% A. Data acquisition was performed in the negative mode using an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source. MS parameters are as follows: the declustering potential was set to −70 V, the collision energy was set to −15 V, and the ion spray voltage was set to −4500 V with a mass range from 100 to 700 m/z. Gas 1 and gas 2 of the ion source were set to 50 psi. Curtain gas was set to 35 psi, and the interface heater temperature was set at 550 °C. TOF-MS/MS was acquired at m/z 515.3. Calibration curves of standards were established by spiking GAA standards into 100 μl blank rat plasma and used for absolute quantitation.

Frailty index

Frailty index score

The mice were scored blindly by experienced research technicians for the onset of various phenotypical parameters once every two months based on previously published protocol56,57. Old mice were observed and compared with young mice to assess the age-associated phenotype, including evaluation of the animal musculoskeletal system, the vestibulocochlear/auditory systems, the ocular and nasal systems, the digestive system, the urogenital system, the respiratory system, signs of discomfort, and body weight (Supplementary Table 3). A score of 0 indicates no sign of frailty, 1 indicates moderate phenotype, 2 indicates a more severe phenotype, 3 indicates severe phenotype, and 4 indicates an extremely severe phenotype.

Frailty index analysis

Mixed-effects model was used to analyze the longitudinal and repeated-measure frailty data. Each mouse is treated as a random effect and GAA treatment and time were considered as fixed effect. Mixed-effects model with unstructured variance structure was applied to estimate the monotonic treatment effect or age-dependent treatment effect in frailty over time. The current lifespan of mice was divided into five quantiles, and the mean frailty index of mice between each two quantiles of lifespan was considered as a morbidity score. The changes in the area under the curve (AUC) were used to calculate the percent compression of morbidity.

Physical function assessments

RotaRod

Mice were given consecutive trainss for 4 days on the RotaRod (Xinruan information and technology Ltd, China) at speeds of 5–8 r.p.m. for 300 s. Next the day, mice were tested on the RotaRod, and the rotation speed was accelerated from 5 to 45 r.p.m. over 10 min. The time was recorded when the mouse dropped off the RotaRod.

Grip

Forelimb grip strength (N) was determined using a Grip Strength Meter (Zhishuduobao Biological Technology Ltd, China). Mice’s forelimbs instinctively griped on a grid attached to a force gauge and were pulled the tail horizontally backward, exerting tension steadily. Grip strength was defined as the maximum strength of the mouse before releasing the grid, with results averaged over 5 trials. Treadmill performance: Treadmill performance was tested in an Animal Treadmill (Zhishuduobao Biological Technology Ltd, China). Mice were acclimated to the treadmill for 4 days for 5–10 min, starting at a speed of 5 m/min for 5 min and progressing to 10 m/min for 5 min. On the test day, mice ran on the treadmill at an initial speed of 10 m/min for 1 min and progressed to 15 m/min for 5 min and then 20 m/min until the mice were exhausted. When mice were stimulated by more than 8 mild electrical shocks at the end of the treadmill within 5 s, the mice were considered exhausted and inability to return to the treadmill. Distance on the treadmill was recorded.

MicroCT analysis

Femora was isolated from mice, and non-osseous tissue was removed. After fixation for two days, the femora were scanned using the Skyscan 1176 in computed tomography (Bruker microCT, Germany). Based on a 3D standard microstructural analysis, reconstructed images were used to quantify morphometric indices, including bone volume fraction (BV/TV, %), average trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, mm), average trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, mm), and trabecular number (Tb.N).

Brain-related behavioral tests

Elevated plus maze

The spontaneous anxiety-like behavior of mice was assessed by the elevated plus maze (Chengdu Techman Software, China). Two open arms (35 × 6 cm) and two closed arms (30 × 6 cm) were attached at right angles to a central platform (6 × 6 cm), elevated 74 cm from the floor. After habituated to the maze, mice were placed in the central area and allowed to explore the maze freely for 5 min. The times entered into and time spent in the open arms and closed arms were recorded.

Open field testing

Mice were habituated for 5 min in the open field chamber (40 × 40 × 40 cm) and then placed for another 5 min in the home cage. Mice were then reintroduced back to the chambers and left to move freely for 5 min. Anxiety was quantified by the ratio of distance in the central 25% of the chamber to the total distance mice traveled and the frequencies of entries central zone. Data were analyzed using Activity Monitor Data Analysis software (Med Associates, Inc.).

Novel object recognition testing

On the first day, all mice were acclimated to the chamber (40 × 40 × 40 cm) arena for 10 min. The next day, the mice were exposed to the chamber containing two identical objects for 10 min. On the third day, each mouse was placed in the chamber again containing one familiar object and one novel object for an additional 10-min test session. The amount of time interacting with the objects was recorded and calculated as percent time interacting with familiar vs novel objects.

Metabolic homeostasis assessment

Mice were deprived of food overnight and then were intraperitoneally injected with a dose of D-glucose (Sigma, USA) at 2 g/kg·bw. Blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (Roche, Germany) at various time points (0, 30, 90, and 120 min). ELISA kits (Elabscience, China) were used to determine the level of insulin in the sera. The levels of TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, TG, and FFA in fasted mice were determined using the reagents (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). The experimental procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Body composition analysis

Body composition was analyzed by Minispec LF50 body composition analyzer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany) based on nuclear magnetic resonance technology. Animals were put into a Minispec probe after analyzer calibration and the contents of each animal’s fat, lean tissues, and free body fluid were measured.

Blood biochemical analysis