Abstract

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) is a prevalent and potentially life-threatening vascular disease including both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. This review will focus on recent insights into the heritable factors that influence an individual’s risk for VTE. Here we will explore not only the discovery of new genetic risk variants but also the importance of functional characterization of these variants. These genome-wide studies should lead to a better understanding of the biological role of genes inside and outside of the canonical coagulation system in thrombus formation and lead to an improved ability to predict an individual’s risk of VTE. Further understanding of the molecular mechanisms altered by genetic variation in VTE risk will be accelerated by further human genome sequencing efforts and the use of functional genetic screens.

Keywords: venous thrombosis, genome-wide association study, CRISPR, anticoagulants, secretory pathway

Common and Rare Genetic Variants

As a complex genetic trait, VTE risk is influenced by different environmental and genetic factors. Previous heritability studies have suggested that ~40% of the risk for all VTE is genetic.1 The genetic architecture of complex genetic traits such as VTE can be divided into two categories, 1: DNA variants that occur frequently in a population and 2: DNA variants that are rare. There is a meaningful distinction between common and rare variants in the genome although there is no definitive (biological) dividing line between the categories. Genetic variants that occur in greater than 1% of a population are generally considered “common” while those less than 1% are described as “rare”.2 Unlike rare variants, common genetic variants can be reliably captured by commercial genotyping arrays, “SNP chips”. These genotyping arrays are designed to genotype previously identified common variants present in the population for many generations and inherited in ancestral haplotype blocks. Other non-genotyped common variants that are in linkage disequilibrium with the genotyped variant can be predicted through a process called imputation.3

Common variant genotypes are used in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to uncover connections between genetic variation and phenotypes such as VTE. While well powered GWAS studies can uncover common variant associations, they also provide data for subsequent polygenic risk scores, colocalization and mendelian randomization studies.4,5 Several large GWAS studies of VTE have been published over the past 10 years. The results of these GWAS and other VTE genetic studies have been recently reviewed in this journal.6 Through GWAS, investigators have confirmed previously described genetic risk factors for thrombosis, such as variation in the ABO (blood group genotypes), F5 (Leiden) and F2 (prothrombin 20210 variant) genes. Expansion of initial VTE GWAS studies into larger meta-analyses have revealed statistically significant associations with common variants at over 90 loci.7–9 GWAS results have been used to create polygenic risk scores (PRS) which have demonstrated that individuals at the highest percentile PRS have VTE risk over 4 times greater than the average and that common variant risk alleles are additive.8

Power to detect significant associations is directly related to the frequency of the variant in a population, the number of people (genomes) examined in a study and the effect size of the variant on the phenotype. Although ABO (major alleles), F5 Leiden and F2 20210 variants are common (> 1% allele frequency) and have reasonably large effect sizes (odds ratios between 1.5 to 3.25)7, most GWAS signals are detected despite a very small overall effect on the phenotype. This high sensitivity is due to the large number of individuals in GWAS and the common allele frequency of the variants. A continuing challenge in the field has been to accurately interpret findings from GWAS studies. Do the signals at these new loci provide clues to interesting underlying pathophysiology much like specific genes in traditionally described single gene disorders? Or are these common variant signals only indirectly associated with the pathophysiology of the phenotypes? What specific variant in the GWAS signal drives the phenotype and by what mechanisms?

Both rare and common variants occur throughout the gene coding (~2.0%) and non-coding (~98%) genome and can be reliably discovered through next generation sequencing. Study of rare genetic variation uncovers interesting contrasts to common variants. At a population level, most genetic variants are rare while at the individual level >95% of variants are common.10 There are estimated to be 50 – 100 de novo genomic variants created with every generation. Rare variants are not included in genotyping arrays and not captured through linkage disequilibrium patterns as they have occurred more recently in the population.11 Unlike common variants, rare coding variants (missense, frame shift, splice site and nonsense) are generally associated with a greater change in the phenotype than common variants. This makes rare, large effect size, nonsynonymous variants potentially useful tools to uncover a gene’s role in the pathophysiology VTE.12 DNA variation occurs most often in the non-translated part of the genome, Here, variants can have a broad range of effects sizes depending on their alteration of gene regulatory function which is an area of intense research.13 To detect a single rare variant’s association with a phenotype, studies would need to include an extraordinarily large number of people to have adequate power. For example, if a variant occurs only once in 100,000 individuals, 1,000,000 individuals would sample that variant ~10 times. To get around this problem, collapsing analyses at the gene or gene pathway are performed with rare variant datasets. Here, each gene captured by genome sequencing is weighted by the number of “qualifying” variants it harbors in cases compared to controls, Figure 1. These studies include variants below a certain threshold of allele frequency, those that are predicted to be damaging to the gene function and those not previously described as benign or causing a gain of function. This enables the 1 in 100,000 variant described above to be aggregated with other rare variants in the gene locus to gain power. The assumption of these collapsing analyses is that different rare variants, damaging to gene function, will accumulate in genes that function to prevent the phenotype. The main assumption in a collapsing analysis is that all qualifying variants have the same effect on gene function. There are many ways to reduce gene function and only a few ways to enhance its function through mutation, making this a reasonable assumption. With notable exceptions, loss of function mutations are more common than gain of function mutations. For example, in VTE we expect rare damaging variants in SERPINC1 (antithrombin), PROC (protein C) and PROS1 (protein S) to occur more frequently in VTE cases compared to controls, as deficiencies of these proteins are well described risk factors for VTE. Indeed, when our group compared rare variants in the exomes of 393 VTE cases to 6114 controls, we identified a significantly higher frequency of qualifying rare variants in PROC, PROS1 and SERPINC1.14 In addition, this study identified STAB2 as a fourth gene that harbored rare damaging variants in VTE cases more than controls. Other groups have similarly detected rare variant burden in the natural anticoagulant genes.15,16 Most recently, a large study leveraging the resources of the UK Biobank investigated the impact of rare and common variants in VTE defined by electronic health records.17 An exome-wide collapsing analysis in 14,723 cases and 334,315 controls confirmed the contributions of rare variants in SERPINC1, PROC, PROS1 and STAB2. Two new loci, PTPT1 and SRSF6 were identified suggesting additional loci harboring rare variants will be identified as larger studies are performed.

Figure 1. Gene Collapsing rare variant burden.

Next generation sequencing identifies rare variants in a hypothetical population of cases and controls where A) illustrates a gene with equal numbers of qualifying rare variants and B) displays a gene with higher frequency of qualifying rare variants in cases compared to controls. If the difference is significant after correction for multiple observations (number of genes examined) then the gene is a candidate risk factor. Down arrow indicates position of DNA variant in coding sequence.

From association signals to functional understanding

Genetic signals from GWAS and whole genome sequencing studies provide clues to underlying biological mechanisms of VTE. Moving from these signals to a better mechanistic understanding remains a challenge for the field. Crosstalk between statistical geneticists, epidemiologists and experts in thrombosis and hemostasis biology will facilitate a better understanding of these genetic signals. Of course, there is no single laboratory method that will inform every VTE association signal. Investigators will need to utilize previous literature examining protein function encoded by genes associated with VTE and existing information about the function of the regulatory region in the intergenic sequence for those SNPs occurring in non-coding regions. This information will guide subsequent functional approaches.

Following up VTE GWAS Studies

In VTE, an incredibly diverse collection of DNA variant association signals have been identified. While large GWAS studies have discovered the greatest number of new genetic associations with VTE, these signals are a challenge to interpret functionally. Although signals in ABO, F5, and F2 had extensive variant functional studies prior to detection in GWAS,18–21 most other GWAS signals had no previous functional connection to VTE risk. Several groups have begun to address these deficiencies in knowledge.

For example, common variants intronic to TSPAN15 are associated with VTE risk, p value 1.67 × 10−16.7 Recently, the TSPAN15 encoded protein has been biologically linked to platelet receptor GPVI (GP6) shedding through regulation of ADAM10 metalloprotease substrate specificity.22 This study used a gene knockout strategy to determine the critical role of TSPAN15 but did not address how mild perturbations from common variants in TSPN15 lead to altered TSPAN15 function.

Common missense variants in SLC44A2 are associated with VTE by GWAS.7 Several groups have studied this association. Slc44a2 deficient mice were studied in a cremaster artery laser injury model and demonstrated impaired clot formation and lower plasma VWF level than littermate controls.23 These Slc44a2 deficient mice did not appear to have other significant differences in a limited sampling of their plasma proteome.24 Slc44a2 deficient mice were noted to have a prolonged bleeding time and decreased thrombus formation in an IVC stenosis model. This affect was also replicated in wild type mice transplanted with Slc44a2 deficient marrow suggesting a cellular source for the effect on thrombosis. Many SLC gene family proteins regulate choline transport. Slc44a2 is expressed in the mitochondria of platelets and plays an important role in platelet energy production and activation.25 While these previous studies used Slc44a2 deficiency as a proxy for the common variant signal, only one group has reported a potential functional change with a top GWAS variant rs2288904-A, encoding an R154Q substitution in SLC44A2. Noting that SLC44A2 is also expressed in neutrophils, they determined that platelets primed by the interaction of glycoprotein Ibα and von Willebrand factor (VWF), under flow conditions, activates αIIbβ3 on the platelet surface allowing for an interaction between platelets and neutrophils though SLC44A2 binding. This platelet neutrophil interaction may enhance thrombosis through a neutrophil extracellular trap mechanism. Here the common variant rs2288904-A is protective against thrombosis by decreasing the binding of primed platelets to neutrophils.26 An additional study has strengthened the connection between this variant and altered neutrophil adhesion and NETosis.27

The top VTE variant at the PROCR locus, rs867186-G encoding the missense variant S219G, has been examined by several groups. Previous to VTE GWAS, this variant was associated with increased plasma concentrations of soluble protein C receptor (sEPCR) and protein C antigen.28,29 Interestingly, this variant was also associated with elevations in plasma factor VII levels and a decreased risk of coronary artery disease.30,31 In 2011, and again in larger VTE GWAS studies, the rs867186-G variant was associated with increased risk for VTE.7,8,32–34 Colocalization studies confirm that the rs867186-G variant is the likely causal variant driving increased factor VII, protein C, activated protein C, DVT risk and protection from coronary artery disease.35 Reconciling how a variant associated with increased plasma protein C levels is paradoxically associated with increased VTE risk was a challenge. Interestingly, individuals with the rs867186-G variant do have higher plasma protein C and sEPCR concentrations but did not have higher activated protein C activity or thrombin-antithrombin levels suggesting the increased plasma sEPCR levels may inhibit the anticoagulant activity of protein C, possibly through decreased EPCR cell membrane concentrations.

Because the risk of VTE is determined, in part, by the plasma concentration of specific pro and anticoagulant proteins,36 GWAS studies for these plasma proteins also inform genetic risk for VTE. GWAS studies for VWF and coagulation protein factor VIII (FVIII) generate strong signals at loci that overlap with VTE GWAS signals suggesting that the variants alter VTE risk through control of VWF/FVIII levels. Those familiar with the biology of VWF and FVIII will not be surprised that the GWAS signals for these related proteins are almost mirror images.30,37 This is due to the reliance of FVIII on VWF for protection against rapid clearance from the blood so that genetic variants associated with VWF variation are also associated with FVIII levels. This mirror image GWAS signal makes it difficult to differentiate thrombosis risk from elevated plasma VWF or from elevated FVIII.

Following up rare variant analyses

In addition to identifying rare variants in known anticoagulant genes (SERPINC1, PROS1 and PROC), our group’s whole exome sequencing analysis of VTE identified an excess of rare damaging mutations in STAB2.14 This gene encodes the scavenger receptor stabilin-2, suggesting a novel mechanism for VTE disease development through altered clearance. Stabilin-2 is expressed in the sinusoidal endothelium of the liver, vascular endothelium of the spleen and lymph nodes.38 In the sinusoidal endothelium, stabilin-2 rapidly cycles between the plasma membrane and cytosol, delivering endocytosed ligands to the lysosome for degradation, thereby regulating plasma ligand levels.39 Previously described stabilin-2 ligands include glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronic acid,40,41 phosphatidylserine exposed cell membranes42 and VWF 43. Reduction of VWF clearance is a possible mechanistic link between stabilin-2 and thrombosis. STAB2 common30 and rare variants14,44,45 associate with changes in VWF levels. VWF is internalized by stabilin-2 expressing cells in vitro, suggesting a role in VWF clearance.43 We expressed a set of rare STAB2 variants identified in our VTE study and demonstrated that these variants led to reduced stabilin-2 cell surface expression.14 In mouse DVT models, Stab2 deficient mice have larger thrombi46 but normal VWF levels, suggesting stabilin-2 may be a critical scavenger of other procoagulant ligands.

Rare Variants causing deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C or protein S

Antithrombin, Protein C, and Protein S deficiencies were originally characterized through clinical and family studies,47–49 followed by specific variant studies in the corresponding SERPINC1, PROC, and PROS1 genes. Interestingly, no common variants in SERPINC1, PROC or PROS1 significantly contribute to VTE risk in reported GWAS in European ancestries, suggesting that variants with effect sizes approaching haploinsufficiency in these genes may be required to precipitate VTE risk. Because the canonical function of these proteins is to limit thrombus progression, we expect VTE disease causing variants to result in qualitative or quantitative deficiencies. An early characterized SERPINC1 variant, antithrombin Toyama (R47C), involved a key residue for heparin binding,50resulting in reduced heparin cofactor binding activity. The first PROC variants identified were observed in a cohort of twenty-nine patients with protein C deficiency, and included nonsense variants as well as missense variants R306X and W402C.51 Shortly after the discovery of protein S, a variant leading to a mid-gene deletion was identified in a family with hereditary thrombophilia through restriction digests and Southern blotting.52

Damaging genetic variants can cause type I or type II deficiencies of these proteins. Generally, a “type I” deficiency results from variants that reduce the antigen levels for any anticoagulant in the bloodstream, while a “type II” deficiency mainly affects the function of each protein without decreasing its plasma concentration.53,54 A rare exception is the “type III” deficiency in protein S, whereby antigen levels for the total protein concentration remain unaffected, while both unbound protein antigen levels and protein activity are decreased.55 Specifically, about 60% of PS in the bloodstream binds the compliment 4 binding protein, which greatly diminishes its anticoagulant activity. The remaining ~40% of PS, referred to as “free PS,” retains its full anticoagulant activity while both unbound protein antigen levels and protein activity are decreased.55 Across all three proteins, type I or III variants can be found across the protein structure, and can encompass many different mutation types. Type II variants in antithrombin and protein C, however, are mainly missense variants, and cluster into critical functional domains, making them particularly useful for identifying characteristics about these domains.53,54 Type II variants rarely occur in patients with protein S deficiency, and most disease variants result in type I or type III deficiencies.55

Functional genomic screens

Forward genetic screens that utilize massively parallel synthetic oligonucleotide arrays are emerging as a useful approach to generate mechanistic data about gene variation. Oligonucleotide arrays can be designed to generate thousands of different guide RNA for CRISPR screens, oligonucleotides designed to encode all possible missense mutations at every single amino acid position in a gene or oligonucleotides designed to encode SNPs or rare variants in tiled segments of the non-coding sequence of the genome. These oligo nucleotide arrays can then be employed in screens to define gene networks critical for specific cellular phenotypes (CRISPR screens), to address coding variants of unknown significance (VUS) (deep mutational scanning), and to identify areas of the non-coding genome that alter gene expression (massively parallel reporter assays).

CRISPR screens

Genes that are critical for normal cellular trafficking of proteins can be identified through CRISPR mediated “knock out” or enhancement screens of genes in cell lines.56 Here, cDNA encoding guide RNA are cloned into a lentiviral vector and transfected with other plasmids to produce a library of lentiviral particles, Figure 2. Libraries of lentiviral preparations can be diluted to favor the targeting of a single gene per cell. These lentiviral particles are highly efficient at transducing model cell lines such as HEK 293 cells, HUVEC cells and Hep G2 cells, and knock out or enhance the expression of a targeted gene in the cell. Transduced cells can be phenotyped by RNA seq or flow cytometry to determine the result of the CRISPR targeting. A genome-wide CRISPR screen using guide RNA targeting over 19,000 genes was performed to identify genes critical for normal PCSK9 secretion from a model cell line. PCSK9 is a secreted convertase that regulates lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) plasma membrane expression. Rare variants causing gain of function in PCSK9 are associated with familial hypercholesterolemia57 while loss of function variants are protective against cardiovascular disease.58 This CRISPR screen identified the endoplasmic reticulum cargo receptor surfeit locus protein 4 encoded by SURF4 as a critical regulator of PCSK9 secretion.59 Although recent GWAS studies of plasma PCSK9 levels do not identify common variants in SURF4 associated with PCSK960, rare variants have not been examined.

Figure 2. CRISPR knock out screen.

A lentiviral library is prepared targeting all genes in genome or a restricted set of candidate genes. Each lentiviral particle encodes a single guide RNA and CRISPR/Cas9 proteins. The lentiviral library is titrated to transduce cells so that most cells are infected by a single particle and results in the loss of function of a single targeted gene. Transduced cells are selected and separated by flow cytometry based on abundance of target protein. Different bins of sorted cells are collected and DNA encoding the guide RNA are identified with next generation sequencing. Genes associated with altered target protein abundance are identified by the enrichment of complementary guide RNA in each bin. Figure created with BioRender.com

Increased concentrations of plasma proteins like VWF, factor VIII, fibrinogen, or decreased levels of protein C, protein S and antithrombin have well described links with VTE risk.61 GWAS signals related to the concentrations of these plasma proteins colocalize with signals from VTE GWAS, suggesting shared signals. Levels of these proteins are maintained by the balance of secretion into the circulation and clearance from the bloodstream. CRISPR knockout screens could be employed to validate GWAS secretory pathway signals and identify additional genes critical for secretion of these VTE related plasma proteins.

Deep Mutational Scanning

Next generation sequencing has become a widely-used tool in clinical diagnoses for many different diseases. The vast majority of variants sequenced in patient populations, however, are difficult to functionally classify.62 As of January 11, 2024, nearly 88% of the missense mutations listed in ClinVar were variants of unknown significance (VUS).62 A VUS within genes in which the discovery of a pathogenic variant within the gene alters clinical management of a related disease are currently a challenge to clinicians and investigators.63 If a VUS is found in such a gene, it is not clear whether an individual’s phenotype is being driven by the variant.

Deep mutational scanning (DMS) was developed as a high throughput method to generate functional data and characterize mutations across an entire gene to reduce the burden of VUS.64 Previous site-directed mutagenesis and computational models have previously lacked scale and accuracy.65 While AlphaFold2 has shown success with predicting some single mutation effects,66,67 it has struggled to predict the functional effect of variants in other proteins,68 particularly SERPINs such as antithrombin.54

To address the increasing number of clinical VUS and provide accurate assessments of their variant effects, deep mutational scans aim to examine all possible missense mutations within a gene. Variants can be produced in cDNA plasmids64 or by CRISPR in the target gene of a cell.63 Each of these mutations is assembled into a cDNA library and expressed in cell lines for transcriptional and functional analyses, Figure 3. The results are quantified into enrichment scores to evaluate the variants’ effects on transcript levels, protein levels, or protein function. Recently, enrichment scores from DMS studies have been used to benchmark the effectiveness of updated variant predictor algorithms,69 including one which incorporates AlphaFold2 to assign pathogenicity prediction scores.70

Figure 3. Deep Mutational Scan.

A library of cells is transfected with a pooled mammalian expression vector encoding all possible single missense variants in a protein or protein domain of interest. Often cells are transfected into a specific locus to normalize expression levels. Transfected cells are selected and sorted based on intracellular fluorescence generated by a fluorescent fusion protein or antibody binding. Alteration of intracellular signal is used as a proxy for the efficiency of secretion of the protein. Sorted cells are collected and DNA encoding the variants are identified with next generation sequencing. Figure created with BioRender.com

Once the mutant alleles are expressed in a cell line, numerous functional analyses can be run in parallel to test the effects of each individual variant upon gene function. For protein coding gene variants, the protein products may also be fused with a reporter protein such as eGFP or mCherry.71 This allows for the variant protein abundance to be assessed by flow cytometry, to determine which alter intracellular protein levels relative to a reference and to select only cells that were successfully transfected. Since protein function depends on having proper abundance, variants reducing protein levels are likely deleterious. Assays may also be designed to test for specific protein-protein interactions72 in order to assess a variant’s effects on function.

DMS studies have focused on intracellular or membrane-bound proteins. Secreted proteins, which account for 10% of the proteins produced in the human body, have posed a particular challenge since the variant protein must remain associated with the cellular genotype that encoded it. Similar to the CRISPR screens described above, investigators have used fluorescently tagged variant proteins to examine the consequences of mutations on secretion from the cell. Here, increases in intracellular fluorescence is used as a proxy for reduced secretion caused by a type I mutation. Type I variants in plasma proteins can also be caused by increased clearance rates and reduced plasma half-life. This has not been addressed by DMS to date.

While changes in intracellular abundance may be an excellent proxy for type I variants that reduce secretion, methods to assess type II variants are also needed. Mammalian cell display, whereby a protein is fused with a linker to a transmembrane protein for analysis on the cell surface is used to keep variant proteins associated with the cell and the variant genotype.73,74 Similar methods, involving yeast and phage display, have yielded successful DMS studies on transmembrane or secreted proteins. In particular, missense mutations in the secreted serpin PAI-1 have been evaluated for their effects on PAI-1 protein-protein interactions and functional stability.75,76 Both yeast and phage display systems cannot provide key posttranslational modification such as cysteine bonds and glycosylation that are necessary for many mammalian proteins, making mammalian cell display an attractive option for evaluating missense variants in secreted proteins.73,74

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays

Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRA) are an emerging tool employed to explore how genetic variation in the non-coding genome alter the expression of nearby genes. These assays work by testing segments of DNA sequence, often sampled from putative cis regulatory regions, inserted upstream of a minimal promoter sequence to measure the alteration of the transcription of a 3’ DNA barcode linked to that specific non-coding segment, Figure 4A. The readout is RNA-seq where the abundance of specific transcripts with the barcode determines the functional effect of the putative regulatory sequence, Figure 4B.77 These assays can assess the function of thousands of potential regulatory sequences in parallel allowing investigators to fine map DNA regulatory sequences. Additionally, confirmed regulatory sequences can be further assessed by targeted mutagenesis of intergenic GWAS SNPs or whole genome sequencing derived rare variants thereby facilitating a functional assay of these variants in the non-coding genome.78 For example, GWAS has identified many different loci affecting variation of skin pigmentation. MPRA was used to survey the function consequences of 1,157 significant GWAS SNPs. Their results suggested that 165 different SNPs altered the expression of 8 different genes associated with skin pigmentation SNPs.79 Potential applications of MSRP in VTE would be to further investigate the cis-regulatory domains of genes near positive GWAS signals or in genes known to be associated with VTE like PROC, PROS1, SERPINC1 and STAB2.

Figure 4. Massively parallel reporter assay.

A) Using putative cis regulatory domain sequence at a gene locus, tiled sequences are synthesized in a massive oligonucleotide array. B) These tiles of genomic DNA sequence are synthesized with a unique DNA sequence barcode and ultimately cloned into individual mammalian expression vectors where a minimal promoter separates the tile from its reporter and/or barcode. Cells are transfected with this library to identify which tiles transcription of RNA barcodes or translation of a reporter protein. RNA seq quantifies the expression level of each tile/barcode, identifying the area of the cis regulatory domain responsible for the enhanced expression. Altered translation of a reporter protein can be measured by flow cytometry and subsequent DNA sequencing. Figure created with BioRender.com

Using Proximity proteomics to define functional pathways in VTE

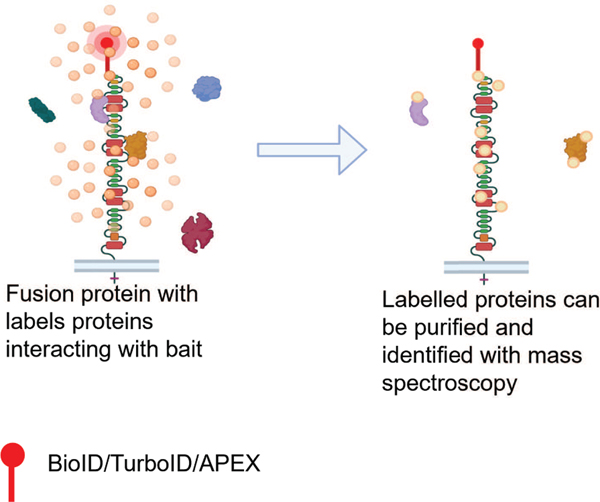

Through whole exome sequencing and GWAS meta-analysis we are identifying new genes and proteins whose functional roles in thrombus development are unknown. We have used proximity biotinylation and proteomics to identify stabilin-2 interacting proteins. As a clearance receptor, we expected stabilin-2 to interact with many different plasma ligands. Identification of specific procoagulant ligands might shed light on how deficiency of this receptor increases VTE risk.

Proximity biotinylation involves the fusion of a protein of interest (bait) to an enzyme that produces reactive biotin molecules. The enzymes commonly used for this technique are derived from either BirA (BioID, TurnoID, MiniTurbo) or APEX (APEX2). The labelling chemistries between these enzymes are slightly different. BirA is a biotin ligase derived from E. coli, which has been modified with a mutation (R118G) that destabilizes the retention of the reactive biotin molecule it normally produces (biotinoyl-5′-AMP) 80. This biotin molecule can subsequently diffuse away from the enzymes active site and covalently bind to nearby primary amine groups on lysine residues, Figure 5. APEX is an ascorbate peroxidase that catalyzes the oxidation of biotin-phenol to a biotin-phenyoxyl radical in the presence of H202. This can bind to electron rich amino acids such as tyrosine and potentially tryptophan, cysteine and histidine) 81,82. Through its fusion to a bait both enzymes can label proteins proximal to the bait. The labelling radius of BirA is ~10nm and APEX ~20nm 81.

Figure 5. Proximity labelling scheme.

cDNA encoding a fusion protein is cloned and expressed in a cell line adding a proximity labeling protein (BioID or APEX) to a bait protein identified in GWAS or rare variant study. Additions of reagents induce biotinylation in vitro. Cell lysates are collected and biotinylated proteins are purified and identified by mass spectroscopy. Figure illustrates an endocytosed transmembrane protein with a terminal proximity labeling fusion indicated by the red lollipop. Figure created with BioRender.com

Interactions in mammalian cells, plants and model organisms can be studied using this technique.83–85 APEX2 has been used to identify proteins important in Weibel Palade body function. Fusion of APEX2 to Rab3b 86 and Rab27a 86,87 has identified a number of Weibel Palade body interacting proteins such as the SNARE interacting protein Munc13–2 and PAK2 which is involved in Weibel Palade body exocytosis. An advantage of this technique includes the ability to analyze interactions in vitro or in vivo in the context of a cell or an organism. Additionally, the technique has an increased ability to detect weak and transient interactions compared to more traditional co-immunoprecipitation experiments as interacting proteins are labelled with biotin. Weak or transient interactions can be lost during sample preparation in co-immunoprecipitation experiments.

We identified stabilin-2 plasma ligands by fusing the enzyme TurboID 88 to the extracellular domains of stabilin-2 and the LDLR as a control. TurboID, derived from BirA has been modified to enable labelling to occur over a 10-minute period 88. T-REx™−293 cells stably expressing these fusion protein constructs were incubated with fibrinogen deficient plasma for 10 minutes, followed by biotin and ATP for 10 minutes to initiate labeling. Biotinylated cell lysate proteins were purified with streptavidin beads and identified using mass spectrometry. Using the REPRINT89, proteins with a SAINT score >0.85 and levels 3-fold greater than LDLR controls, were considered stabilin-2 specific ligands.90,91 These results support the use of proximity labeling to further probe the function of newly identified proteins playing a role in VTE risk.

Conclusions

Genetic investigation of VTE risk continues to reveal new associations with genetic variants outside of the traditional hemostasis and thrombosis gene network. Larger studies will continue to uncover common genetic variants with small effect sizes while larger rare-variant sequencing studies will identify genes and gene pathways important in VTE risk. Follow up of these studies is critical to understand the mechanisms driving the associations. Several different types of genetic screens offer high throughput assessments of single variant functions and should facilitate a better understanding of human genetic variation and VTE risk.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: KCD, CB and MU have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Zoller B, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. A sibling based design to quantify genetic and shared environmental effects of venous thromboembolism in Sweden. Thromb Res. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goswami C, Chattopadhyay A, Chuang EY. Rare variants: data types and analysis strategies. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(12):961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torkamaneh D, Belzile F. Accurate Imputation of Untyped Variants from Deep Sequencing Data. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2243:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hindy G, Tyrrell DJ, Vasbinder A, et al. Increased soluble urokinase plasminogen activator levels modulate monocyte function to promote atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klarin D, Busenkell E, Judy R, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of venous thromboembolism identifies new risk loci and genetic overlap with arterial vascular disease. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1574–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han J, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Rosendaal FR. Genomic science of risk prediction for venous thromboembolic disease: convenient clarification or compounding complexity. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(12):3292–3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Germain M, Chasman DI, de Haan H, et al. Meta-analysis of 65,734 Individuals Identifies TSPAN15 and SLC44A2 as Two Susceptibility Loci for Venous Thromboembolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghouse J, Tragante V, Ahlberg G, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 93 risk loci and enables risk prediction equivalent to monogenic forms of venous thromboembolism. Nat Genet. 2023;55(3):399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thibord F, Klarin D, Brody JA, et al. Cross-Ancestry Investigation of Venous Thromboembolism Genomic Predictors. Circulation. 2022;146(16):1225–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lappalainen T, Scott AJ, Brandt M, Hall IM. Genomic Analysis in the Age of Human Genome Sequencing. Cell. 2019;177(1):70–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupski JR, Belmont JW, Boerwinkle E, Gibbs RA. Clan genomics and the complex architecture of human disease. Cell. 2011;147(1):32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kierczak M, Rafati N, Hoglund J, et al. Contribution of rare whole-genome sequencing variants to plasma protein levels and the missing heritability. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boye C, Kalita CA, Findley AS, et al. Characterization of caffeine response regulatory variants in vascular endothelial cells. Elife. 2024;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desch KC, Ozel AB, Halvorsen M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies rare variants in STAB2 associated with venous thromboembolic disease. Blood. 2020;136(5):533–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seyerle AA, Laurie CA, Coombes BJ, et al. Whole Genome Analysis of Venous Thromboembolism: the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Program. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2023;16(2):e003532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang W, Stimson MR, Basu S, et al. Burden of rare exome sequence variants in PROC gene is associated with venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(2):445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He XY, Wu BS, Yang L, et al. Genetic associations of protein-coding variants in venous thromboembolism. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koeleman BP, Reitsma PH, Allaart CF, Bertina RM. Activated protein C resistance as an additional risk factor for thrombosis in protein C-deficient families. Blood. 1994;84(4):1031–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoller B, Berntsdotter A, Garcia de Frutos P, Dahlback B. Resistance to activated protein C as an additional genetic risk factor in hereditary deficiency of protein S. Blood. 1995;85(12):3518–3523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertina RM, Koeleman BP, Koster T, et al. Mutation in blood coagulation factor V associated with resistance to activated protein C. Nature. 1994;369(6475):64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poort SR, Rosendaal FR, Reitsma PH, Bertina RM. A common genetic variation in the 3’-untranslated region of the prothrombin gene is associated with elevated plasma prothrombin levels and an increase in venous thrombosis. Blood. 1996;88(10):3698–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koo CZ, Matthews AL, Harrison N, et al. The Platelet Collagen Receptor GPVI Is Cleaved by Tspan15/ADAM10 and Tspan33/ADAM10 Molecular Scissors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilburg J, Adili R, Nair TS, et al. Characterization of hemostasis in mice lacking the novel thrombosis susceptibility gene Slc44a2. Thromb Res. 2018;171:155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilburg J, Michaud SA, Maracle CX, et al. Plasma Protein Signatures of a Murine Venous Thrombosis Model and Slc44a2 Knockout Mice Using Quantitative-Targeted Proteomics. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(3):423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett JA, Mastrangelo MA, Ture SK, et al. The choline transporter Slc44a2 controls platelet activation and thrombosis by regulating mitochondrial function. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Constantinescu-Bercu A, Grassi L, Frontini M, Salles II C, Woollard K, Crawley JT. Activated alpha(IIb)beta(3) on platelets mediates flow-dependent NETosis via SLC44A2. Elife. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zirka G, Robert P, Tilburg J, et al. Impaired adhesion of neutrophils expressing Slc44a2/HNA-3b to VWF protects against NETosis under venous shear rates. Blood. 2021;137(16):2256–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiner AP, Carty CL, Jenny NS, et al. PROC, PROCR and PROS1 polymorphisms, plasma anticoagulant phenotypes, and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(10):1625–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang W, Basu S, Kong X, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for plasma levels of protein C: the ARIC study. Blood. 2010;116(23):5032–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith NL, Chen MH, Dehghan A, et al. Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: The CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology) Consortium. Circulation. 2010;121(12):1382–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howson JMM, Zhao W, Barnes DR, et al. Fifteen new risk loci for coronary artery disease highlight arterial-wall-specific mechanisms. Nat Genet. 2017;49(7):1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Germain M, Saut N, Greliche N, et al. Genetics of venous thrombosis: insights from a new genome wide association study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindstrom S, Brody JA, Turman C, et al. A large-scale exome array analysis of venous thromboembolism. Genet Epidemiol. 2019;43(4):449–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindstrom S, Wang L, Smith EN, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic association studies identify 16 novel susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2019;134(19):1645–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stacey D, Chen L, Stanczyk PJ, et al. Elucidating mechanisms of genetic cross-disease associations at the PROCR vascular disease locus. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan S, Titova OE, Zhang K, et al. Plasma protein and venous thromboembolism: prospective cohort and mendelian randomisation analyses. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(4):783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabater-Lleal M, Huffman JE, de Vries PS, et al. Genome-Wide Association Transethnic Meta-Analyses Identifies Novel Associations Regulating Coagulation Factor VIII and von Willebrand Factor Plasma Levels. Circulation. 2019;139(5):620–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Politz O, Gratchev A, McCourt PA, et al. Stabilin-1 and −2 constitute a novel family of fasciclin-like hyaluronan receptor homologues. Biochem J. 2002;362(Pt 1):155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGary CT, Raja RH, Weigel PH. Endocytosis of hyaluronic acid by rat liver endothelial cells. Evidence for receptor recycling. Biochem J. 1989;257(3):875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weigel PH. Discovery of the Liver Hyaluronan Receptor for Endocytosis (HARE) and Its Progressive Emergence as the Multi-Ligand Scavenger Receptor Stabilin-2. Biomolecules. 2019;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yannariello-Brown J, Frost SJ, Weigel PH. Identification of the Ca(2+)-independent endocytic hyaluronan receptor in rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cells using a photoaffinity cross-linking reagent. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(28):20451–20456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park SY, Jung MY, Kim HJ, et al. Rapid cell corpse clearance by stabilin-2, a membrane phosphatidylserine receptor. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(1):192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swystun LL, Lai JD, Notley C, et al. The endothelial cell receptor stabilin-2 regulates VWF-FVIII complex half-life and immunogenicity. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(9):4057–4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huffman JE, de Vries PS, Morrison AC, et al. Rare and low-frequency variants and their association with plasma levels of fibrinogen, FVII, FVIII, and vWF. Blood. 2015;126(11):e19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pankratz N, Wei P, Brody JA, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of 14 389 individuals from the ESP and CHARGE consortia identifies novel rare variation associated with hemostatic factors. Hum Mol Genet. 2022;31(18):3120–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michels A, Swystun LL, Dwyer CN, et al. Stabilin-2 deficiency increases thrombotic burden and alters the composition of venous thrombi in a mouse model. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(10):2440–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broekmans AW, Bertina RM, Reinalda-Poot J, et al. Hereditary protein S deficiency and venous thrombo-embolism. A study in three Dutch families. Thromb Haemost. 1985;53(2):273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egeberg O. Inherited Antithrombin Deficiency Causing Thrombophilia. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1965;13:516–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin JH, Evatt B, Zimmerman TS, Kleiss AJ, Wideman C. Deficiency of protein C in congenital thrombotic disease. J Clin Invest. 1981;68(5):1370–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koide T, Odani S, Takahashi K, Ono T, Sakuragawa N. Antithrombin III Toyama: replacement of arginine-47 by cysteine in hereditary abnormal antithrombin III that lacks heparin-binding ability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(2):289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grundy C, Plendl H, Grote W, Zoll B, Kakkar VV, Cooper DN. A single base-pair deletion in the protein C gene causing recurrent thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 1991;61(3):335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ploos van Amstel HK, Huisman MV, Reitsma PH, Wouter ten Cate J, Bertina RM. Partial protein S gene deletion in a family with hereditary thrombophilia. Blood. 1989;73(2):479–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alhenc-Gelas M, Plu-Bureau G, Mauge L, Gandrille S, Presot I, Thrombophilia GSGoG. Genotype-Phenotype Relationships in a Large French Cohort of Subjects with Inherited Protein C Deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(9):1270–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corral J, de la Morena-Barrio ME, Vicente V. The genetics of antithrombin. Thromb Res. 2018;169:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marlar RA, Gausman JN, Tsuda H, Rollins-Raval MA, Brinkman HJM. Recommendations for clinical laboratory testing for protein S deficiency: Communication from the SSC committee plasma coagulation inhibitors of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(1):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris JA, Sun JS, Sanjana NE. Next-generation forward genetic screens: uniting high-throughput perturbations with single-cell analysis. Trends Genet. 2024;40(2):118–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34(2):154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr., Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emmer BT, Hesketh GG, Kotnik E, et al. The cargo receptor SURF4 promotes the efficient cellular secretion of PCSK9. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kheirkhah A, Schachtl-Riess JF, Lamina C, et al. Meta-GWAS on PCSK9 concentrations reveals associations of novel loci outside the PCSK9 locus in White populations. Atherosclerosis. 2023;386:117384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd, Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maes S, Deploey N, Peelman F, Eyckerman S. Deep mutational scanning of proteins in mammalian cells. Cell Rep Methods. 2023;3(11):100641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Findlay GM, Daza RM, Martin B, et al. Accurate classification of BRCA1 variants with saturation genome editing. Nature. 2018;562(7726):217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fowler DM, Fields S. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nat Methods. 2014;11(8):801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McBride JM, Polev K, Abdirasulov A, Reinharz V, Grzybowski BA, Tlusty T. AlphaFold2 Can Predict Single-Mutation Effects. Phys Rev Lett. 2023;131(21):218401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reynisdottir T, Anderson KJ, Boukas L, Bjornsson HT. Missense variants causing Wiedemann-Steiner syndrome preferentially occur in the KMT2A-CXXC domain and are accurately classified using AlphaFold2. PLoS Genet. 2022;18(6):e1010278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buel GR, Walters KJ. Can AlphaFold2 predict the impact of missense mutations on structure? Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2022;29(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Livesey BJ, Marsh JA. Updated benchmarking of variant effect predictors using deep mutational scanning. Mol Syst Biol. 2023;19(8):e11474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmidt A, Roner S, Mai K, Klinkhammer H, Kircher M, Ludwig KU. Predicting the pathogenicity of missense variants using features derived from AlphaFold2. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matreyek KA, Starita LM, Stephany JJ, et al. Multiplex assessment of protein variant abundance by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Genet. 2018;50(6):874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kretz CA, Dai M, Soylemez O, et al. Massively parallel enzyme kinetics reveals the substrate recognition landscape of the metalloprotease ADAMTS13. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(30):9328–9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fowler D. What do we need to scale multiplexed assays to all genes in the genome? Mutational Scanning Symposium; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fowler D. Understanding genetic variants, from technology development to the clinic. National Human Genome Research Institute Webinar series; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haynes LM, Huttinger ZM, Yee A, et al. Deep mutational scanning and massively parallel kinetics of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 functional stability to probe its latency transition. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(12):102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huttinger ZM, Haynes LM, Yee A, et al. Deep mutational scanning of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 functional landscape. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng Y, VanDusen NJ. Massively Parallel Reporter Assays for High-Throughput In Vivo Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiao F, Zhang X, Morton SU, et al. Functional dissection of human cardiac enhancers and noncoding de novo variants in congenital heart disease. Nat Genet. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Feng Y, Xie N, Inoue F, et al. Integrative functional genomic analyses identify genetic variants influencing skin pigmentation in Africans. Nat Genet. 2024;56(2):258–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choi-Rhee E, Schulman H, Cronan JE. Promiscuous protein biotinylation by Escherichia coli biotin protein ligase. Protein Sci. 2004;13(11):3043–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trinkle-Mulcahy L. Recent advances in proximity-based labeling methods for interactome mapping. F1000Res. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lam SS, Martell JD, Kamer KJ, et al. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Agbo L, Blanchet SA, Kougnassoukou Tchara PE, Fradet-Turcotte A, Lambert JP. Comprehensive Interactome Mapping of Nuclear Receptors Using Proximity Biotinylation. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2456:223–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Artan M, Barratt S, Flynn SM, et al. Interactome analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans synapses by TurboID-based proximity labeling. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(3):101094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Song G, Lal NK, et al. TurboID-based proximity labeling reveals that UBR7 is a regulator of N NLR immune receptor-mediated immunity. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Holthenrich A, Drexler HCA, Chehab T, Nass J, Gerke V. Proximity proteomics of endothelial Weibel-Palade bodies identifies novel regulator of von Willebrand factor secretion. Blood. 2019;134(12):979–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.El-Mansi S, Robinson CL, Kostelnik KB, et al. Proximity proteomics identifies septins and PAK2 as decisive regulators of actomyosin-mediated expulsion of von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2023;141(8):930–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Branon TC, Bosch JA, Sanchez AD, et al. Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(9):880–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mellacheruvu D, Wright Z, Couzens AL, et al. The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat Methods. 2013;10(8):730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Underwood M, Golden K, Desch K. Identifying novel stabilin-2 plasma ligands using proximity labeling Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Vol. 6; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Underwood M, Golden K, Desch K. Identification and Validation of Novel Stabilin-2 Plasma Ligands. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Vol. 7; 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]