Abstract

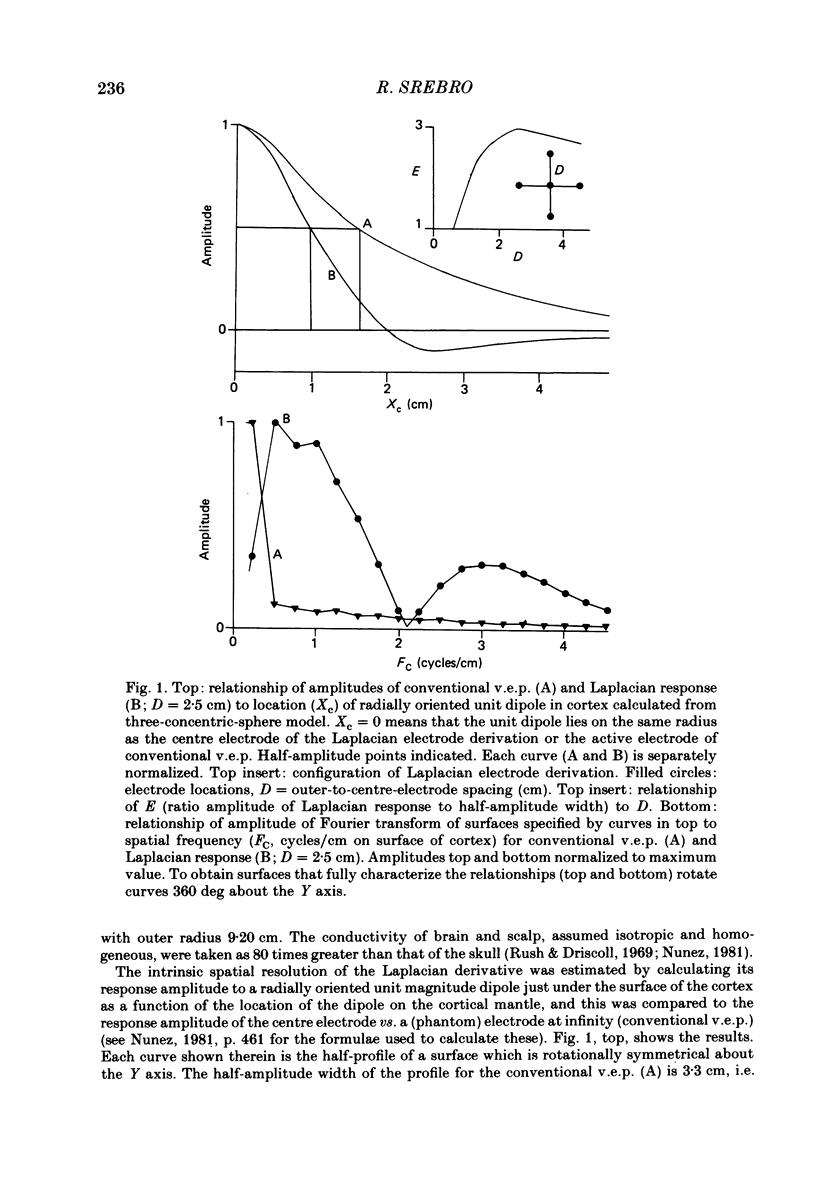

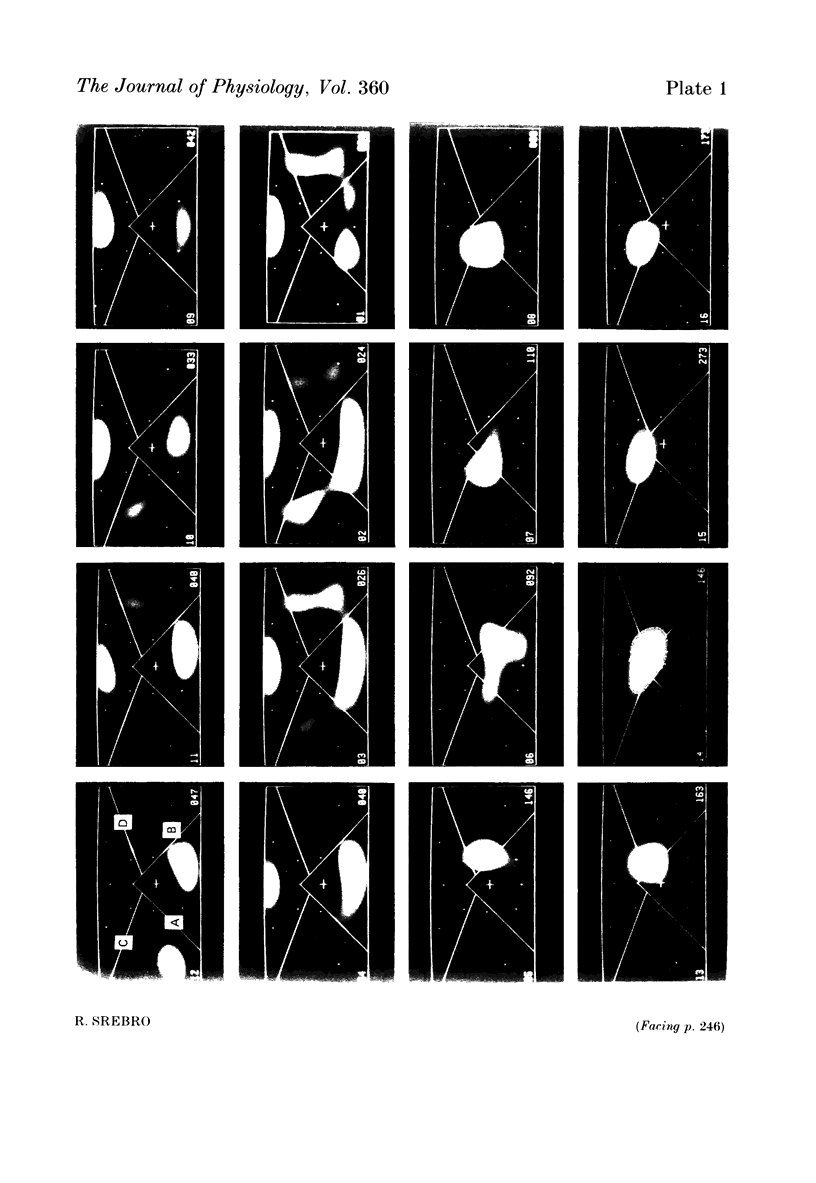

The locations of cortical activity evoked by visual stimuli presented at different positions in the visual field are deduced from the scalp topography of visually evoked potentials in humans. To accomplish this, the Laplacian evoked potential is measured using a multi-electrode array. It is shown that the Laplacian response has the following useful attributes for this purpose. It is reference-free. Its spatial resolution is approximately 2 cm referred to the surface of the cortex. Its spatial sensitivity characteristic is that of a spatial band-pass filter. It is relatively insensitive to source--sink configurations that are oriented tangentially to the surface of the scalp. Only modest assumptions about the source--sink configuration are required to obtain a unique inversion of the scalp topography. Stimuli consisting of checkerboard-filled octant or annular octant segments are presented as appearance-disappearance pulses at sixteen different positions in the visual field in randomized order. The locations of evoked cortical activity in the occipital, parietal and temporal lobes are represented on a Mercator projection map for each octant or octant segment stimulated. Lower hemifield stimuli activate cortex which lies mainly on the convexity of the occipital lobe contralateral to the side of stimulus presentation in the visual field. The more peripheral the stimulus is in the visual field, the more rostral is the location of the active cortex. The rostral-to-caudal location of the evoked activity varies from subject to subject by as much as 3 cm on the surface of the occipital cortex. Furthermore, in any single subject there is a substantial amount of hemispheric asymmetry. Upper hemifield stimuli activate cortex that lies on the extreme caudal pole of the occipital lobe. This activity is relatively weak, and in some subjects it is almost unmeasurable. It is suggested that the representation of the upper hemifield in the cortex lies mostly on the inferior and mesial walls of the occipital lobe and possibly within the calcarine fissures. Those locations are inaccessible to the Laplacian analysis because the current generators therein may be oriented tangentially to the surface of the overlying scalp. Posterior parietal lobe activity and/or inferior temporal lobe activity is frequently evoked. Different subjects have different patterns of evoked activity. Unilateral or bilateral posterior parietal lobe activity is the most common pattern. Unilateral inferior temporal lobe activity is a less common pattern.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blumhardt L. D., Barrett G., Kriss A., Halliday A. M. The pattern-evoked potential in lesions of the posterior visual pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;388:264–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb50796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley G. S., Lewin W. S. The sensations produced by electrical stimulation of the visual cortex. J Physiol. 1968 May;196(2):479–493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley G. S. The variability of the human striate cortex. J Physiol. 1972 Sep;225(2):1P–3P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darcey T. M., Ary J. P., Fender D. H. Spatio-temporal visually evoked scalp potentials in response to partial-field patterned stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980 Dec;50(5-6):348–355. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster J. M., Jervey J. P. Neuronal firing in the inferotemporal cortex of the monkey in a visual memory task. J Neurosci. 1982 Mar;2(3):361–375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00361.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C. G., Bender D. B., Gerstein G. L. Activity of inferior temporal neurons in behaving monkeys. Neuropsychologia. 1979;17(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(79)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimovic I. C., Pedley T. A. Hemi-field pattern reversal visual evoked potentials. II. Lesions of the chiasm and posterior visual pathways. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982 Aug;54(2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday A. M., Michael W. F. Changes in pattern-evoked responses in man associated with the vertical and horizontal meridians of the visual field. J Physiol. 1970 Jun;208(2):499–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C. J., Butler S. R., Glass A. The localization of equivalent dipoles of EEG sources by the application of electrical field theory. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1975 Aug;39(2):117–130. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(75)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek R. S., Sances A., Jr, Jodat R. W., Larson S. J. The contributions of intracerebral currents to the EEG and evoked potentials. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1978 Sep;25(5):405–413. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1978.326337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys D. A., Axford J. G. Source locations of pattern-specific components of human visual evoked potentials. I. Component of striate cortical origin. Exp Brain Res. 1972;16(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00233371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys D. A. Cortical source locations of pattern-related visual evoked potentials recorded from the human scalp. Nature. 1971 Feb 12;229(5285):502–504. doi: 10.1038/229502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys D. A., Smith A. T. The polarity inversion of scalp potentials evoked by upper and lower half-field stimulus patterns: latency or surface distribution differences? Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1979 Apr;46(4):409–415. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh R. N., Darcey T. M., Lehmann D., Fender D. H. Evaluation of methods for three-dimensional localization of electrical sources in the human brain. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1978 Sep;25(5):421–429. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1978.326339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee M., Rall W. Computed potentials of cortically arranged populations of neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1977 May;40(3):647–666. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman D., Meles H. P., Mir Z. Average multichannel EEG potential fields evoked from upper and lower hemi-retina: latency differences. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1977 Nov;43(5):725–731. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(77)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesevre N., Joseph J. P. Modifications of the pattern-evoked potential (PEP) in relation to the stimulated part of the visual field (clues for the most probable origin of each component). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1979 Aug;47(2):183–203. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay D. M. Source density analysis of scalp potentials during evaluated action. II. Lateral distributions. Exp Brain Res. 1984;54(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00235821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D., Hildreth E. Theory of edge detection. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980 Feb 29;207(1167):187–217. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1980.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael W. F., Halliday A. M. Differences between the occipital distribution of upper and lower field pattern-evoked responses in man. Brain Res. 1971 Sep 24;32(2):311–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami A., Kubota K. Inferotemporal neuron activities and color discrimination with delay. Brain Res. 1980 Jan 20;182(1):65–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motter B. C., Mountcastle V. B. The functional properties of the light-sensitive neurons of the posterior parietal cortex studied in waking monkeys: foveal sparing and opponent vector organization. J Neurosci. 1981 Jan;1(1):3–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-01-00003.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle V. B., Andersen R. A., Motter B. C. The influence of attentive fixation upon the excitability of the light-sensitive neurons of the posterior parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 1981 Nov;1(11):1218–1225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-11-01218.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley R. M., Hester N. S., Ettlinger G. Stimulus- and response-dependent units from the occipital and temporal lobes of the unanaesthetized monkey performing learnt visual tasks. Exp Brain Res. 1977 Apr 21;27(5):539–552. doi: 10.1007/BF00239042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls E. T., Judge S. J., Sanghera M. K. Activity of neurones in the inferotemporal cortex of the alert monkey. Brain Res. 1977 Jul 15;130(2):229–238. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush S., Driscoll D. A. Current distribution in the brain from surface electrodes. Anesth Analg. 1968 Nov-Dec;47(6):717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush S., Driscoll D. A. EEG electrode sensitivity--an application of reciprocity. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1969 Jan;16(1):15–22. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1969.4502598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON F. N., BAYLEY R. H. The electric field of an eccentric dipole in a homogeneous spherical conducting medium. Circulation. 1950 Jan;1(1):84–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.1.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin G., Stålberg E. Source derivation in clinical routine EEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980 Nov;50(3-4):282–292. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]