Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the effect of different postoperative radiotherapy doses on the prognosis of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

Methods

A total of 199 patients (aged 18–75 years) with locally advanced ESCC who underwent esophagectomy and postoperative radiotherapy/chemoradiotherapy at the Fujian Cancer Hospital between July 2008 and January 2018 were included. Based on the postoperative radiotherapy dose, the patients were divided into a low‐dose group (50–50.4 Gy; median dose 50 Gy) and a high‐dose group (>50.4 Gy; median dose 60 Gy). Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy regimens included PF (fluorouracil and cisplatin) and TP (paclitaxel and cisplatin) regimens. Patients were followed‐up every 3 months in the first 2 years after surgery, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and then subsequently once a year. The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) rates. The propensity‐score matching (PSM) method was applied to identify a 1:1, well‐balanced matched cohort with 33 patients in each group for survival comparison.

Results

Among the 199 patients enrolled in this study, 144 and 55 were in the low‐dose and high‐dose groups, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that pathological N classification, vascular tumor emboli, and postoperative radiotherapy dose were independent prognostic factors for both OS and PFS, all p < 0.05. Before PSM, the OS and the PFS of the low‐dose group were significantly longer than those of the high‐dose group, both p < 0.05. After PSM, better OS and PFS rates were observed in the low‐dose group, both p < 0.05. The results showed that patients with pathological stages N0–2 or N3, negative surgical margins, and no vascular tumor emboli could obtain a significant benefit in both OS and PFS after treatment with a low dose of postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). In the subgroup with positive surgical margins, treatment with a low dose of postoperative radiotherapy offered a non‐significant survival benefit compared to treatment with a high dose of postoperative radiotherapy.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that for patients with ESCC, the low‐dose group (50–50.4 Gy) had a significantly higher OS and PFS than the high‐dose group (>50.4 Gy). It was suggested that 50–50.4 Gy might be the recommended postoperative radiotherapy dose for ESCC patients.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, postoperative radiotherapy, propensity score matching, radiation dose

Postoperative radiotherapy is widely used as the adjuvant treatment for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) patients. However, there is no unified standard about the optimal postoperative radiotherapy dose for ESCC patients. In this retrospective study, a total of 199 patients with locally advanced ESCC who underwent esophagectomy and postoperative radiotherapy at Fujian cancer hospital from July 2008 to January 2018 were analyzed. The patients were divided into the low–dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose: 50–50.4 Gy) and the high–dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose: > 50.4Gy) to investigate the impact of different postoperative radiotherapy doses on the prognosis of ESCC. The propensity–score matching (PSM) method was applied to identify a 1:1, well–balanced matched cohort with 33 patients in each group for survival comparison. Our results showed that the OS and the PFS of the low–dose group were significantly longer than those of the high–dose group.

1. INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer, one of the most common gastrointestinal malignant tumors, seriously endangers human health. 1 In China, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the primary pathological type of esophageal cancer. 2 The symptoms of early‐stage ESCC are insidious, and most have already developed into a locally advanced stage when diagnosed. The 5‐year survival rate of patients with locally advanced ESCC who undergo surgery alone is less than 30%. 3 Local‐regional recurrence is the most common cause of treatment failure. 4

Patients with locally advanced ESCC usually receive neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of local‐regional recurrence. 5 Multiple studies have demonstrated significant benefits of neoadjuvant therapy in the survival of patients with locally advanced ESCC. 6 , 7 , 8 However, postoperative radiotherapy is widely used as an adjuvant treatment for patients with locally advanced ESCC in China. Several retrospective studies have shown that adjuvant radiotherapy for locally advanced ESCC improves the local control rate and overall survival (OS). 9 , 10 Lin et al. retrospectively analyzed 5640 patients with ESCC, and found that patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy had better OS and progression‐free survival (PFS) than those who received surgery alone, and adjuvant radiotherapy significantly reduced the local recurrence rate. 11 However, there is no unified standard about the optimal postoperative radiotherapy dose for ESCC patients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend a postoperative radiotherapy dose of 45–50.4 Gy for esophageal cancer, whereas the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend 50–56 Gy as the postoperative radiotherapy dose for ESCC. In practice, a 50–60 Gy or even a high dose is used for postoperative radiotherapy. Whether a high dose of >50.4 Gy is required for postoperative radiotherapy of ESCC is unknown. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the prognosis of ESCC patients treated with low‐dose postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy) and those who received high‐dose postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy) using the propensity score‐matching method.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patients

A total of 199 patients with locally advanced ESCC who underwent esophagectomy and postoperative radiotherapy at the Fujian Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, China) between July 2008 and January 2018 were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histological confirmation of ESCC without evidence of distant metastases; (2) age range of 18–75 years, and with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2; (3) underwent esophagectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy; and (4) received intensity‐modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with a total dose ≥50 Gy. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of other malignant tumors; (2) perioperative death; (3) received neoadjuvant radiotherapy before surgery; and (4) missed clinical data. The ethics committee of Fujian Cancer Hospital approved this study for non‐interventional research.

2.2. Chemoradiotherapy

Radiotherapy was delivered by the IMRT technique using a 6‐MV photon beam from a linear accelerator. The clinical target volume (CTV) included the high‐risk lymph node drainage area and the primary tumor bed. The planning target volume (PTV) was defined as a 5‐mm margin of the CTV for tumor motion and setup variations. The PTV received a total dose ranging from 50 to 67 Gy in 1.8–2 Gy daily fractions, five fractions per week. Based on the postoperative radiotherapy dose, the patients were divided into a low‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose 50–50.4 Gy; median dose 50 Gy) and a high‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose >50.4 Gy; median dose 60 Gy). Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy regimens included PF (fluorouracil and cisplatin) and TP (paclitaxel and cisplatin) regimens.

2.3. Surgery

All patients completed the routine preoperative examination, which included clinical history, physical examination, hematological and biochemical examinations, chest enhancement CT, electronic gastroscopy, abdominal ultrasound, or abdominal CT, and, in some cases, a bone scan or positron emission tomography. Subsequently, an esophagectomy with two‐ or three‐field lymph node dissection was performed.

2.4. Follow‐up

Patients were followed‐up every 3 months in the first 2 years after surgery, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and then subsequently once a year. The follow‐up evaluation included medical history, physical examination, hematological examination, chest and abdominal CT, and esophageal radiography. Some patients were also examined using a bone scan or positron emission tomography. The primary endpoints of our data analysis were OS and PFS rates.

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) statistical software was used for statistical analysis. Pearson's χ2‐test was used to compare the differences between the baseline clinicopathological characteristics of the groups. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for OS analysis. The log‐rank test was used for univariate analysis. Variables with significant differences screened by univariate analysis were analyzed using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The propensity score matching (PSM) method was applied to reduce selection bias and balance confounding variables. The χ2‐test was used to test the balance of the matched variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients’ characteristics

Among the 199 patients enrolled in the present study, 144 and 55 were in the low‐dose and high‐dose groups, respectively. The data cut‐off for follow‐up was August 22, 2020. The follow‐up time was 0–127 months, with a median follow‐up duration of 108 months. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, tumor location, pN classification, vascular tumor emboli, nerve invasion, tumor length, tumor thickness, or the number of adjuvant chemotherapy cycles between the low‐ and high‐dose groups. Pathological stage, pT classification, surgical margin status, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly differed between the low‐ and high‐dose groups.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients before and after matching.

| Pre‐matched | Matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Low dose | High dose | p | Low dose | High dose | p |

| Age (years) | 0.943 | 0.805 | ||||

| <60 | 89 | 25 | 17 | 18 | ||

| ≥60 | 66 | 19 | 16 | 15 | ||

| Sex | 0.066 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 122 | 40 | 29 | 30 | ||

| Female | 33 | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Tumor location | 0.628 | 0.366 | ||||

| Upper | 35 | 12 | 6 | 11 | ||

| Middle | 82 | 24 | 19 | 15 | ||

| Lower | 38 | 8 | 8 | 7 | ||

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | 0.800 | ||||

| IIB‐IIIB | 125 | 22 | 20 | 21 | ||

| IVA‐IVB | 30 | 22 | 13 | 12 | ||

| pT classification | 0.006 | 0.796 | ||||

| T1‐3 | 126 | 27 | 22 | 21 | ||

| T4 | 29 | 17 | 11 | 12 | ||

| pN classification | 0.203 | 0.523 | ||||

| N0‐2 | 138 | 36 | 28 | 26 | ||

| N3 | 17 | 8 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Surgical margin | 0.001 | 0.353 | ||||

| Positive | 8 | 9 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Negative | 147 | 35 | 25 | 28 | ||

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.935 | 0.618 | ||||

| Yes | 68 | 19 | 13 | 15 | ||

| No | 87 | 25 | 20 | 18 | ||

| Nerve invasion | 0.116 | 0.284 | ||||

| Yes | 41 | 17 | 8 | 12 | ||

| No | 114 | 27 | 25 | 21 | ||

| Tumor length (cm) | 0.519 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≤5.0 | 110 | 29 | 21 | 21 | ||

| >5.0 | 45 | 15 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Tumor thickness (cm) | 0.898 | 0.614 | ||||

| ≤1.4 | 97 | 28 | 21 | 19 | ||

| <1.4 | 58 | 16 | 12 | 14 | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.004 | 0.757 | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 12 | 6 | 7 | ||

| No | 139 | 32 | 27 | 26 | ||

| No. adjuvant chemotherapy cycles | 0.404 | 0.796 | ||||

| ≤2 | 95 | 30 | 11 | 12 | ||

| >2 | 60 | 14 | 22 | 21 | ||

3.2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of OS and PFS

Univariate analysis showed that the pN classification, vascular tumor emboli, and postoperative radiotherapy dose were significantly related to OS and PFS. The significant factors in the univariate analysis were analyzed using the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. Multivariate analysis further demonstrated that pN classification, vascular tumor emboli, and postoperative radiotherapy dose were independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with overall survival: univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | p | HR (95.0% CI) | p | HR (95.0% CI) |

| Age (years) | 0.993 | 0.998 (0.676–1.475) | ||

| Sex | 0.705 | 1.101 (0.669–1.812) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.856 | 1.044 (0.656–1.661) | ||

| Pathological stage | 0.468 | 0.849 (0.547–1.320) | ||

| pT classification | 0.592 | 0.884 (0.563–1.388) | ||

| pN classification | 0.001 | 0.449 (0.274–0.734) | 0.029 | 0.566 (0.340–0.942) |

| Surgical margin | 0.974 | 0.989 (0.498–1.962) | ||

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.008 | 0.591 (0.400–0.874) | 0.049 | 0.668 (0.447–0.998) |

| Nerve invasion | 0.257 | 0.787 (0.520–1.191) | ||

| Tumor length (cm) | 0.222 | 0.775 (0.515–1.167) | ||

| Tumor thickness (cm) | 0.881 | 1.031 (0.691–1.539) | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.122 | 0.669 (0.402–1.113) | ||

| Radiation dose (cGy) | <0.001 | 0.397 (0.262–0.601) | <0.001 | 0.427 (0.280–0.650) |

| No. adjuvant chemotherapy cycles | 0.494 | 1.152 (0.768–1.728) | ||

TABLE 3.

Factors associated with progression‐free survival: univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) |

| Age (years) | 0.806 | 0.949 (0.623–1.444) | ||

| Sex | 0.284 | 1.367 (0.772–2.420) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.990 | 0.997 (0.605–1.641) | ||

| Pathological stage | 0.953 | 0.985 (0.597–1.625) | ||

| pT classification | 0.583 | 0.872 (0.534–1.422) | ||

| pN classification | 0.004 | 0.458 (0.269–0.780) | 0.042 | 0.566 (0.327–0.980) |

| Surgical margin | 0.905 | 0.957 (0.462–1.981) | ||

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.006 | 0.557 (0.365–0.848) | 0.015 | 0.584 (0.379–0.901) |

| Nerve invasion | 0.600 | 0.885 (0.560–1.398) | ||

| Tumor length (cm) | 0.379 | 0.819 (0.525–1.278) | ||

| Tumor thickness (cm) | 0.858 | 0.962 (0.629–1.472) | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.364 | 0.768 (0.433–1.359) | ||

| Radiation dose (cGy) | <0.001 | 0.445 (0.284–0.698) | <0.001 | 0.440 (0.280–0.692) |

| No. adjuvant chemotherapy cycles | 0.479 | 1.169 (0.758–1.803) | ||

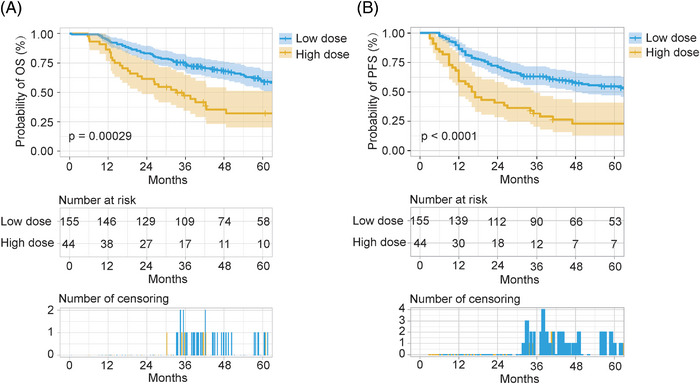

3.3. OS and PFS before PSM

The median OS of the entire group was 42.17 months, and the 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year survival rates were 92.5%, 68.7%, and 54%, respectively. The median OS and the 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year survival rates of the low‐dose group were significantly higher than those of the high‐dose group (median OS 47.17 months vs. 32.32 months, 1‐year OS rates 94.2% vs. 86.4%, 3‐year OS rates 74.8% vs. 47.2%, 5‐year OS rates 60.0% vs. 32.2%, p = 0.00029), as shown in Figure 1A. The median PFS was 37 months in the entire group, and the 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year PFS rates were 80.4%, 56.2%, and 47.8%, respectively. The median PFS and the l‐, 3‐, and 5‐year PFS rates of the low‐dose group were significantly higher than those of the high‐dose group (median PFS 41 months vs. 16.5 months, 1‐year PFS rates 86.5% vs. 59.1%, 3‐year PFS rates: 63.2% vs. 31.7%, 5‐year PFS rates 54.7% vs. 23.1%, p < 0.0001), as shown in Figure 1B.

FIGURE 1.

Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) of patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who have undergone esophagectomy before propensity score matching. (A) Overall survival. (B) Progression free survival. Low dose: postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). High dose: postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy).

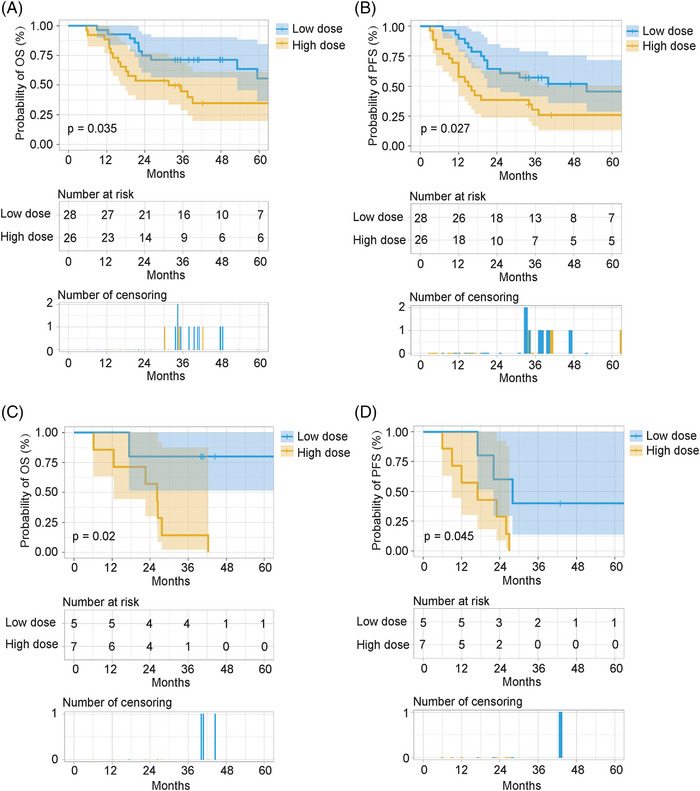

3.4. OS and PFS after PSM

Next, we used PSM to balance the covariates between the two groups. The covariates were age, sex, tumor location, pathological stage, pT and pN classifications, surgical margin status, vascular tumor emboli, nerve invasion, tumor length, tumor thickness, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the number of adjuvant chemotherapy cycles. The covariates were matched using the 1:1 nearest‐neighbor method, and we extracted a well‐balanced matched cohort with 33 patients in each group (Table 1).

After matching, longer OS and PFS were observed in the low‐dose group than in the high‐dose group. The median OS was 40.67 months in the low‐dose group and 26.4 months in the high‐dose group, respectively. The 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year OS rates in the low‐dose group were 97.0%, 72.7%, and 58.2%, respectively, whereas those in the high‐dose group were 87.9%, 38.4%, and 26.9%, respectively (p = 0.0027; Figure 2A). The median PFS was 33 and 16 months in the low‐dose and high‐dose groups, respectively. The 1‐year, 3‐year, and 5‐year PFS rates in the low‐dose group were 90.9%, 54.5%, and 44.8%, respectively, whereas those in the high‐dose group were 57.6%, 23.9%, and 20.5%, respectively (p = 0.0047; Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) of patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who have undergone esophagectomy after propensity score matching. (A) Overall survival. (B) Progression free survival. Low dose: postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). High dose: postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy).

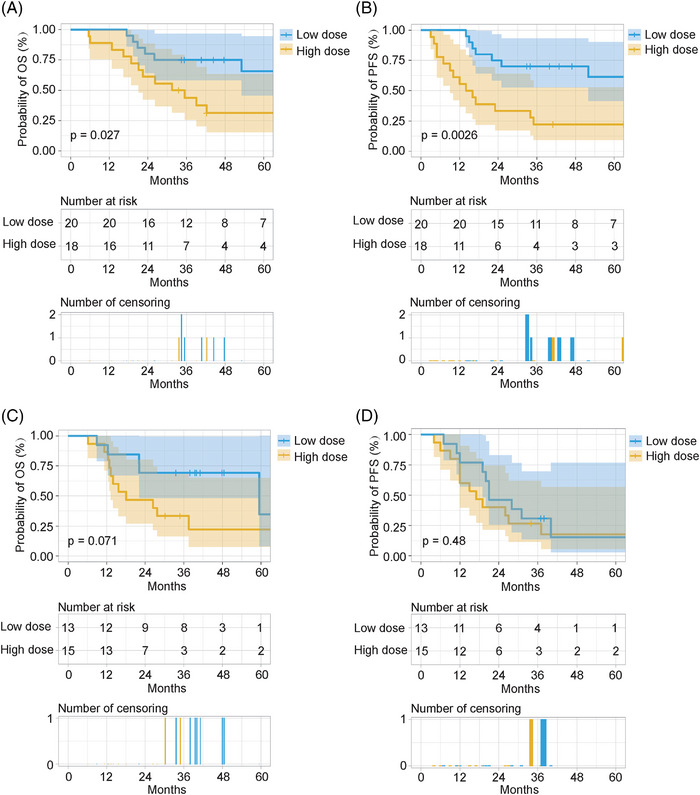

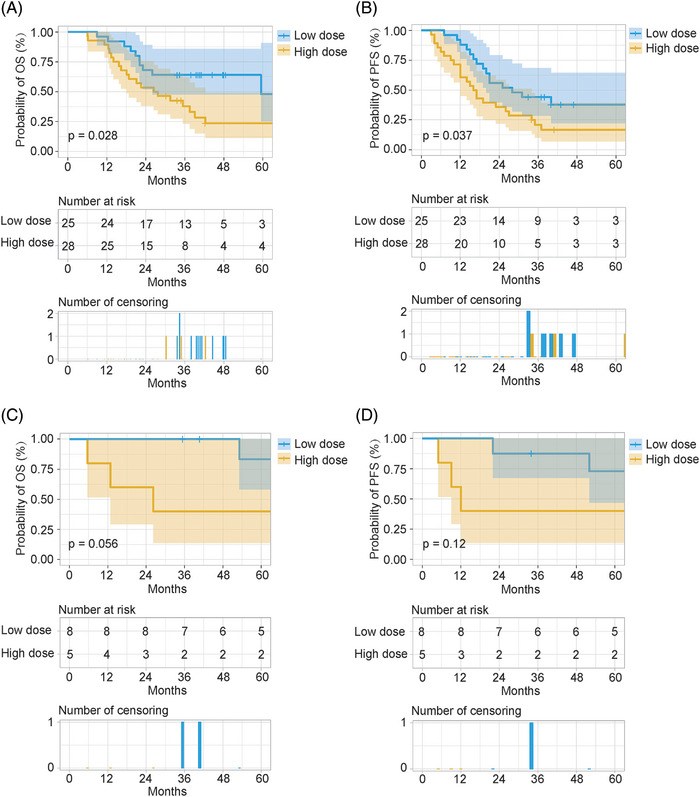

3.5. Subgroup analyses

To investigate the effect of the postoperative radiotherapy dose on the prognosis of patients with different clinical characteristics, we performed a subgroup analysis. Based on the multivariate analysis of OS and PFS, subgroup analysis was performed according to pN classification and vascular tumor emboli. Furthermore, patients with a positive surgical margin were usually recommended to receive a high dose of definitive radiotherapy. Therefore, subgroup analysis based on surgical margin status was also performed. The results showed that patients with pathological stages N0‐2 or N3, negative surgical margins, and no vascular tumor emboli could obtain a significant benefit in both OS and PFS after treatment with a low dose of postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). Of note, in the subgroup with positive surgical margins, treatment with a low dose of postoperative radiotherapy offered a non‐significant survival benefit compared with treatment with a high dose of postoperative radiotherapy (Figures 3, 4, 5).

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analysis based on pN classification. Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) in the pN0‐2 subgroup; OS and PFS in the pN3 subgroup. (A,C) OS. (B,D) PFS. Low dose: postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). High dose: postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy).

FIGURE 4.

Subgroup analysis based on vascular tumor emboli. Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) in the no vascular tumor emboli subgroup; OS and PFS in the vascular tumor emboli subgroup. (A,C) OS. (B,D) PFS. Low dose: postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). High dose: postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy).

FIGURE 5.

Subgroup analysis based on surgical margin status. Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) in the negative surgical margin subgroup; OS and PFS in the positive surgical margin subgroup. (A,C) OS. (B,D) PFS. Low dose: postoperative radiotherapy (50–50.4 Gy). High dose: postoperative radiotherapy (>50.4 Gy).

4. DISCUSSION

Previous research has shown that patients with locally advanced ESCC treated with surgery alone have a poor prognosis due to local‐regional recurrence and distant metastases. 4 Therefore, the recommended treatment modality for operable locally advanced ESCC was a combination of surgical resection, systemic chemotherapy, and local radiotherapy. 5 In China, postoperative radiotherapy is widely used as an adjuvant treatment to reduce the recurrence rate of locally advanced ESCC. 11 However, the optimal postoperative radiotherapy dose for patients with locally advanced ESCC remains unclear. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the impact of different postoperative radiotherapy doses on the prognosis of patients with ESCC using PSM. The results showed that patients who received 50–50.4 Gy of postoperative radiotherapy had significantly higher OS and PFS than those who received more than 50.4 Gy of postoperative radiotherapy. The present findings have significant implications for the choice of the optimal postoperative radiotherapy dose for locally advanced ESCC.

Many factors can affect the prognosis of patients with locally advanced ESCC after surgery, including the number of lymph node metastases, depth of tumor infiltration, pathological stage, tumor location, tumor differentiation degree, and so on. 12 , 13 The present study showed that pN classification, vascular tumor emboli, and postoperative radiotherapy dose were independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS in patients with locally advanced ESCC receiving surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. The radiotherapy dose is usually a critical factor for the prognosis of patients treated with radiotherapy. Stereotactic body radiotherapy with a high biologically equivalent dose can achieve efficacy comparable with surgery, particularly in patients with early‐stage non‐small cell lung cancer. 14 , 15 However, few studies have investigated the impact of the postoperative radiotherapy dose on ESCC prognosis. Therefore, we compared the prognoses of different postoperative radiotherapy doses. We divided the patients into a low‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose 50–50.4 Gy) and a high‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose >50.4 Gy). Furthermore, the present results demonstrated that the low‐dose group had a significantly higher OS and PFS than the high‐dose group. The question then is: why did high‐dose postoperative radiotherapy not result in a higher OS or PFS? Previous studies have shown that irradiation of the mediastinal lymph nodes may lead to lymphopenia, which could further lower immunity and affect prognosis. 16 , 17 Therefore, we speculated that a high dose of postoperative radiotherapy might lead to more toxicities and lower immunity, and these factors may have contributed to the poor prognosis of the high‐dose group.

Definitive postoperative chemoradiotherapy was used to treat residual tumors in patients with positive surgical margin. 18 The optimal dose of definitive radiotherapy for patients with ESCC remains controversial. 19 Brower et al. retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 6854 patients with esophageal cancer who received chemoradiotherapy using modern radiotherapy techniques between 2004 and 2012 from the National Cancer Database. Their results found no improvement in the OS of esophageal cancer patients with dose escalation to over 50.4 Gy. 20 In contrast, a systematic review by Sun et al. indicated that, compared with low‐dose radiotherapy, ≥60 Gy radiotherapy might improve OS and local‐regional control. 21 The NCCN guidelines recommend a definitive radiotherapy dose of 50–50.4 Gy for esophageal cancer. In contrast, the Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend 50–60 Gy or even higher as the definitive radiotherapy dose in practice. Recently, a prospective, multicenter, randomized study from China reported the difference between definitive radiotherapy doses of 50 Gy and 60 Gy in terms of efficacy and safety for patients with ESCC. Their results suggested that the 60 and 50 Gy groups had similar prognoses, but the 50 Gy group had a lower rate of severe pneumonia. 22 These findings have important implications for the recommendation of 50 Gy as the definitive radiation dose for patients with ESCC. Consistent with the above study, the subgroup analysis in the present study suggested that patients with positive surgical margins cannot benefit from radiotherapy doses >50.4 Gy. There was a non‐significant survival benefit in the 50–50.4 Gy group compared with the >50.4 Gy group, which might be due to lower rates of toxicities in the low‐dose group. However, this is only a possible explanation, because we did not collect information on the toxicities in either group.

There were some limitations to the present study. First, although we used the PSM method to reduce selection bias and balance confounding variables, this was a retrospective study with a limited number of patients. Second, our study did not collect information on toxicities, which is essential for explaining the prognosis results.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that the low‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose 50–50.4 Gy) had significantly higher OS and PFS rates than the high‐dose group (postoperative radiotherapy dose >50.4 Gy). It was suggested that 50–50.4 Gy might be the recommended postoperative radiotherapy dose for ESCC patients. Future studies should explore the use of <50 Gy postoperative radiotherapy in treating patients with ESCC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Q.W. Yao and J.C. Li designed this study. H.Y. Zheng, S.Y. Huang, and M.Q. Lin contributed to data collection. H.Y. Zheng, S.Y. Huang, and Q.W. Yao analyzed the data. Q.W. Yao and J.C. Li supervised this study. H.Y. Zheng and Q.W. Yao wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and revised the manuscript. The authors (s) read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The ethics committee of Fujian Cancer Hospital approved this study for Non‐Interventional Research (K2022‐085‐01).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (2019Y9041), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81803037), and National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Program (Grant No. 2021). We thank all the authors and those who helped in preparing the study.

Yao Q, Zheng H, Huang S, Lin M, Yang J, Li J. Low versus high dose of postoperative radiotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score‐matched analysis. Prec Radiat Oncol. 2023;7:101–110. 10.1002/pro6.1192

Qiwei Yao and Hongying Zheng contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abnet CC, Arnold M, Wei WQ. Epidemiology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):360‐373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (NEOCRTEC5010): a phase III multicenter, randomized, open‐label clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(27):2796‐2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelly RJ. Emerging multimodality approaches to treat localized esophageal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(8):1009‐1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watanabe M, Otake R, Kozuki R, et al. Recent progress in multidisciplinary treatment for patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2020;50(1):12‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan KKW, Saluja R, Delos Santos K, et al. Neoadjuvant treatments for locally advanced, resectable esophageal cancer: A network meta‐analysis. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(2):430‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yuan M, Bao Y, Ma Z, Men Y, Wang Y, Hui Z. The optimal treatment for resectable esophageal cancer: a network meta‐analysis of 6168 patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:628706. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.628706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, et al. Long‐term efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for the treatment of locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the NEOCRTEC5010 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):721‐729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lv J, Cao XF, Zhu B, Ji L, Tao L, Wang DD. Long‐term efficacy of perioperative chemoradiotherapy on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(13):1649‐1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen J, Pan J, Liu J, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy for node‐positive thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):671‐677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin HN, Chen LQ, Shang QX, Yuan Y, Yang YS. A meta‐analysis on surgery with or without postoperative radiotherapy to treat squamous cell esophageal carcinoma. Int J Surg. 2020;80:184‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ning ZH, Zhao W, Li XD, et al. The status of perineural invasion predicts the outcomes of postoperative radiotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(6):6881‐6890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu S, Anfossi S, Qiu B, et al. Prognostic factors for locoregional recurrence in patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radical two‐field lymph node dissection: results from long‐term follow‐up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(4):966‐973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kepka L, Socha J. Dose and fractionation schedules in radiotherapy for non‐small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(4):1969‐1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang JY, Mehran RJ, Feng L, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for operable stage I non‐small‐cell lung cancer (revised STARS): long‐term results of a single‐arm, prospective trial with prespecified comparison to surgery. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1448‐1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zou L, Chu L, Xia F, et al. Is clinical target volume necessary?‐A failure pattern analysis in patients with locally advanced non‐small cell lung cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy using intensity‐modulated radiotherapy technique. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9(5):1986‐1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Venkatesulu BP, Mallick S, Lin SH, Krishnan S. A systematic review of the influence of radiation‐induced lymphopenia on survival outcomes in solid tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;123:42‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Otake R, Okamura A, Yamashita K, et al. Efficacy of postoperative radiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients with positive circumferential resection margin. Esophagus. 2021;18(2):288‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sasaki Y, Kato K. Chemoradiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(9):805‐810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brower JV, Chen S, Bassetti MF, et al. Radiation dose escalation in esophageal cancer revisited: a contemporary analysis of the national cancer data base, 2004 to 2012. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(5):985‐993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun X, Wang L, Wang Y, et al. High vs. low radiation dose of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma with modern radiotherapy techniques: a meta‐analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1222. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu Y, Dong B, Zhu W, et al. A phase III multicenter randomized clinical trial of 60 Gy versus 50 Gy radiation dose in concurrent chemoradiotherapy for inoperable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(9):1792‐1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]