Abstract

This paper aims to evaluate the general state of the medical services provided by the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital (SCJU Craiova) and to compare the perceived quality of the services between 2016-2019 and 2022-2023. The method chosen to carry out the research was through the collection and analysis of data from the hospital’s questionnaire for quality assessment, voluntarily filled in by patients. We analyzed the trends and the variability of the satisfaction reports for each period, separately, and then between the 2016-2019 and 2022-2023 periods. As a comparison, we observed that the rating of the healthcare services and staff behavior is more polarized in the post-pandemic period as it was before, while the assessment of the hotel conditions shows that, even if the objective conditions have improved, the patients tend to be more critical.

Keywords: Healthcare services , quality assessment , satisfaction questionnaire

Introduction

Patient satisfaction significantly impacts access to medical services, serving as a key indicator of the quality of care provided by a healthcare system. Satisfied patients are more likely to return to the same hospital, and evaluating their satisfaction helps healthcare providers understand and meet patients' expectations.

Centralizing and analyzing this information reveals the degree of patient satisfaction regarding the services and conditions offered. This analysis forms a general impression of perceived quality, enabling informed decision-making to improve care.

Measuring the quality of medical care

According to Donabedian's classic paper [1], the quality of healthcare can be assessed through three dimensions: structure, process, and outcome. Donabedian stated, “a good structure increases the probability of a good process, and a good process increases the probability of a good outcome” [1].

Donabedian's dimensions should not be interpreted mechanically. It is a mistake to think that only the structure influences the process and that the result has no influence on the structure and the processes. Therefore, it is more appropriate to consider Donabedian's dimensions as inter-related units, where each component affects the others, creating a dynamic quality management system where outcomes can, in turn, influence both structure and process. This model offers a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions at play, facilitating effective improvements in the quality of medical care.

Healthcare services are delivered by officially recognized institutions aimed at addressing the health needs of the population through a wide range of preventive, curative, and rehabilitative activities, utilizing specialists with various roles. The World Health Organization defines the quality of a health system as "the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes" [2].

Patients and their families assess the quality of medical services based on their experiences when they have to deal with medical care: the responsiveness of nurses, the demeanor of doctors, the hospital environment, and the available resources-all these factors shape beneficiaries' perceptions of the service provider.

On the other hand, for hospitals, quality means very specific clinical data collected and analyzed over a certain period of time.

Measuring the quality of the medical act is not always easy. Agencies and companies have different ways of reporting clinical outcomes, which influence how they evaluate a hospital regarding a certain quality aspect.

Maxwell and Donabedian's interpretations of quality are comparable to the components of quality outlined by the WHO Working Group on Quality, according to which quality must reflect at least the following four essential concepts [2]:

1. Technical quality

2. Resource utilization (economic efficiency)

3. Risk management

4. Patient satisfaction

Factors affecting quality

The number of patients a hospital treats for a certain condition or performs a certain procedure on, as well as the severity of patients' illnesses at admission, are two critical factors influencing assessments of care quality. Evidence suggests that higher quality care correlates with treating a greater number of patients for particular conditions or procedures, especially when they are complex or risky. The severity of a patient's illness is also a key factor in evaluating care quality within a hospital and affects overall clinical outcomes.

Key stakeholders in healthcare services include patients, medical institutions, professionals, health institution management, government, and other funders [3].

Each of these groups has distinct perspectives on quality:

-Patients, as healthcare consumers, often lack in-depth medical knowledge and view quality in terms of health outcomes and satisfaction. For them, interpersonal relationships are paramount, followed by professional competence.

-Medical staff and managers prioritize professional expertise, technical equipment, and the impacts of these factors on patient health. Doctors, in particular, may emphasize technical skills over interpersonal relationships.

-Financiers (government or other payers) typically associate quality with efficiency and optimal resource use, a view often mirrored by health facility managers who seek to project competence and excellence.

Evaluation of Patient Satisfaction

A beneficiary/patient focus is a fundamental principle of quality management systems [4].

Assessing patient satisfaction is essential, as it reflects how well service providers meet both expressed and unexpressed patient expectations.

Patient satisfaction can be assessed through various methods [5].

Pragmatically, it reflects the extent to which a patient's expectations are met. Patients instinctively or consciously have and form expectations regarding their interactions with doctors, nurses, care conditions, and clinical outcomes. The alignment between expectations and experiences is critical; when experiences deviate negatively from expectations, dissatisfaction arises. Conversely, if expectations are met, patients tend to leave feeling satisfied. Satisfaction is shaped by all experiences, professional interactions, and the patient's health status following care.

Most patients may lack the expertise to evaluate the technical and professional competence of their providers but are acutely aware of their experiences and feelings. Their satisfaction is often linked to the ease of communication and their perception of the convenience of the medical service [6].

This emphasis on quality leads to:

-positive patient behaviors (such as adherence to treatment and continuity of care)

-a favorable image of the healthcare service

-overall patient satisfaction

Therefore, a patient's perception of service quality is a consequence of their healthcare experience rather than an inherent attribute of the care itself. There is not always a direct correlation between patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. Some experts argue that the quality of the patient-provider relationship and effective communication are more significant determinants of satisfaction than the technical quality of care. Satisfied patients are generally more willing to cooperate, which can enhance their healing potential.

From a specialist's perspective, patient satisfaction contributes to psychological well-being, influencing care outcomes and overall impact. A satisfied and informed patient is more likely to cooperate with their doctor and follow recommendations, which enhances access to medical services-satisfied patients are more likely to return to the same provider [7].

At the same time, evaluating the satisfaction of medical staff is essential, though the findings may differ from patient assessments. Patients often focus on interpersonal relationships, which they can easily perceive, while technical aspects may be more challenging for them to evaluate. If, as a result of the medical procedure, which was carried out as expected, patient's health does not improve as anticipated, even exceptional care quality can be deemed "meaningless" [6].

Factors such as the patient's particular circumstances or their willingness to engage in their care can affect outcomes.

Recognizing satisfaction as a distinct dimension of quality is important, as many healthcare interactions are unique and cannot be replicated. Therefore, a negative experience can significantly impact overall satisfaction, even if the clinical outcomes are favorable.

Patients form a general, global impression of the care received, reflecting their overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction. They may also have varying opinions regarding specific aspects of care, leading to different evaluations of individual elements.

Satisfaction greatly influences the interpersonal relationships that develop during care. It is beneficial for patients-especially those with chronic conditions or requiring preventive examinations-to consistently receive services from the same institution and medical personnel. Continuity of care fosters familiarity and trust, which many specialists consider vital for quality.

Often, medical staff may overlook the importance of communication, respect, politeness, and empathy in patient interactions. Recognizing the significant role that human factors play in patient satisfaction and health outcomes is crucial for enhancing the overall quality of care, directly influencing the healing result, through patient's willingness to cooperate [8].

Materials and Methods

Aim of the study

The purpose of this analysis was the comparative evaluation of SCJU Craiova patients' expectations, by measuring their degree of satisfaction regarding the accessibility and quality of the medical services provided by the hospital in the period 2016-2019, respectively in the period 2022-2023.

Considering the epidemiological context generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which determined a very low number of hospitalized patients (Figure 1) and the performance of the medical act under much stricter conditions, we decided not to use the data from January 1, 2020-December 31, 2021.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the number of admissions in the analyzed period

Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital (SCJU Craiova) is located in Craiova, the capital city of Dolj county and the most important city in the South-West region of Romania, making it the most important hospital on a territory of about 150km in diameter, and providing medical services for the city of Craiova and more than 110 other localities. The population served is of approximately 690,257 inhabitants, distributed in proportion of 54.00% in urban areas and 46.00% in rural areas, in a constant process of demographic aging determined by the increase of the adult and elderly population simultaneously with the decrease in the number of young people.

The hospital is public and under the direct management of the Ministry of Health, being a rank II hospital, according to Romanian classification. It was accredited by the National Authority of Quality Management in Health with the maximum level of trust in December 2015. The hospital has 1,488 beds for continuous hospitalization plus 38 beds for day hospitalization, with 36 clinics and compartments, both for internal medicine and surgery.

Data Collection

In this study, we wanted to assess the general level of the perceived quality of the medical services provided, as well as the level of kindness of the medical staff, the way in which the activity of the medical staff is perceived, the hotel conditions, cleanliness, food quality, the quality of the care received, the degree of respecting patients' rights and the way the are given needed information, medication sourcing, and the willingness of treated patients to utilize hospital services again.

The method chosen to carry out the research was through the collection and analysis of data from the hospital’s questionnaire for quality assessment, voluntarily filled in by patients. The questionnaire includes demographic data about the participant (age, education, area of residence-rural or urban, marital status, approximate financial situation) and questions regarding the quality of the medical act they benefit from, and the performance of the trained medical personnel.

The patient satisfaction questionnaire can be completed after admission, when it is distributed to all patients by the medical registrar or ward nurse in each medical clinic, at the moment of the opening of the general clinical observation sheet. When the questionnaire is handed out to the patient, he is instructed on how to fill it in, specifying that it is anonymous and voluntary, as well as how to submit of the questionnaire in the designated collection place-questionnaires are submitted in the special box at the level of each section. The collection of the filled-in questionnaires is done in the first week of each month, for the previous month, by the members of the Health Services Quality Management Service (SMCSS). The collected questionnaires are statistically analyzed, monthly, according to the structure of questions in the questionnaire, by the same Service.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the trends and the variability of the satisfaction reports for each period, separately, and then between the 2016-2019 and 2022-2023 periods (pre- versus post-pandemic).

We computed the average percentages for each of the possible answers reported, and we used statistical tests for proportions to determine whether there are significant differences between the aforementioned periods of time.

Data were recorded using Microsoft Excel files (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), then it was statistically analyzed using z-test for proportions and Chi Square with the XLSTAT add-on for MS Excel (Addinsoft SARL, Paris, France).

Results

We analyzed the collected data on the following issues:

- general satisfaction level of patients

- the level of satisfaction related to the quality of healthcare services

- the level of satisfaction related to the interactions with the hospital staff

- the level of satisfaction related to the quality of hotel services, cleanliness and food quality

- the level of satisfaction related to the regarding the degree to which patients' rights were respected and the quality of information given to the patients

- the percentage of patients who stated that they received medication and materials in full from the hospital

- the percentage of patients who stated that they would still use the services offered by SCJU Craiova

It was noticed that there is a great variability in the proportion of total number of patients of questionnaires received from different clinics, with some of them collecting 10 times less questionnaires than others, while others do not collect questionnaires at all.

In order to have a better overall image of quality, it is necessary to increase the number of patients who fill in satisfaction questionnaires, the responsibility for this activity being assigned to the head nurses.

From the analysis of the data regarding the general satisfaction of patients at SCJU Craiova, an increase in the percentage of patients who answered very satisfied, in the post-pandemic period, with an average of 38.61%, compared to the period before the pandemic, where the average was of 25.52% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the overall degree of satisfaction regarding the admission

There is also a decrease in the percentage of responses of patients who declared themselves partially satisfied after the pandemic, with an average of 44.83%, compared to the 2016-2019 period, where the average was 64.96%.

Regarding the percentage of partially dissatisfied patients, there was an increase in the period 2022-2023, with an average of 7.87%, compared to the period before the pandemic, when the average was 3.80%.

Regarding dissatisfied patients, the average from 2016-2019 was 0.30%, but it increased slightly in the post-Covid period reaching an average of 0.44%.

Finally, patients who declared themselves very dissatisfied had an average of 4.02 before the pandemic, which subsequently decreased to 3.08% in 2022-2023.

In the period 2022-2023, the percentage of patients who declared themselves very satisfied and partially satisfied was over 83%, compared to the period 2016-2019 when the percentage was over 90%.

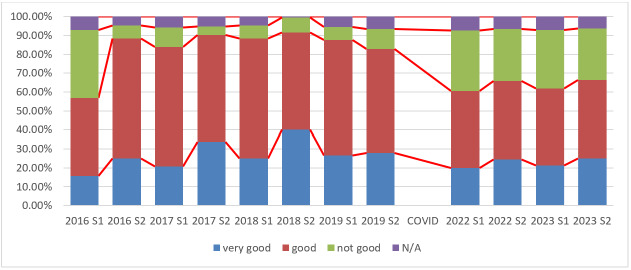

Analyzing the degree of satisfaction related to the quality of medical services and interactions with medical and non-medical hospital staff (Figure 3), there is an increase in patients who gave the rating “very good”, with an average of 44.61%, for 2022-2023, compared to the 2016-2019 period, when the average was 30.85%.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to the quality of medical services and staff interactions

However, there was a decrease in the percentage of patients who gave the rating “good” in the post-pandemic period, where the average was 38.48%, compared to the pre-pandemic period, with an average of 63.01%. Regarding the unsatisfactory (“not good”) rating, there was an increase in the 2022-2023 period, where the average was 9.87%, compared to the period before the pandemic, which had an average of 2.02%.

As a conclusion, In the 2022-2023 period, the percentage of “very good” and “good” answers was over 83%, compared to the 2016-2019 period, when the percentage was over 93%, so we can say that patients' demands have increased (z-test p value<0.001).

Even if the percentages differ, we found similar evidence in similar studies concerning the pre- and post-pandemic patient’s satisfaction in Romania [9, 10].

From the analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to the friendliness of the medical staff, for doctors, nurses and hospital attendants (Figure 4, 5, 6), the same patterns are found as for the general impression on medical services, but with higher increases in the “very good” rating given to doctors and nurses, and a smaller increase in nurses, for the post-pandemic period, compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to doctors’ behavior

Figure 5.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to nurses’ behavior

Figure 6.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to hospital attendants’ behavior

Regarding the hotel conditions at SCJU Craiova, it was observed that the percentage of responses rated as “very good” varied from 2016-2019, primarily due to the modernization of certain areas, with an average rating of 29.84% (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to hotel conditions

In the post-pandemic period, the average rating for patients who selected “very good” stabilized at around 32%.

However, the percentage of patients rating their experience as “good” decreased during the period 2022-2023, averaging 40.18%, compared to 58.88% during 2016-2019.

Additionally, there was an increase in the percentage of patients reporting dissatisfaction with hospital accommodation in the post-pandemic period, averaging 19.18%, compared to just 6.43% in the pre-pandemic period.

Overall, the combined percentage of patients rating their accommodation as either “good” or “very good” fell from over 88% in the pre-pandemic period to approximately 73% in the post-pandemic period (z-test p value<0.001).

These findings are also reflected in the answers regarding the assessment of the degree of cleanliness (Figure 8), which shows similar results.

Figure 8.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to cleanliness

Regarding the quality of the food (Figure 9), there was a decrease in the post-pandemic period of the percentage of patients who rated it as “very good”, the average being 22.66%, compared to the pre-pandemic period, when the average was 26.83%.

Figure 9.

Analysis of the degree of satisfaction related to food quality

Also, there was a decrease of the percentage of patients who choose the rating “good”, the average being 41.02% in the 2022-2023 period, compared to 56.87%, as it was in the 2016-2019 period.

A noticeable increase was observed among patients who assessed the quality of food as unsatisfactory, after the pandemic, with an average of 29.5%, compared to an average of 11.3% before the pandemic.

Overall, the average percentage of “good” and “very good” answers decreased from over 83% before the pandemic, to 64% in the post-pandemic period (z-test p value<0.001).

Analyzing the data regarding the degree to which patients' rights were respected, it was found that in the 2022-2023 period, the percentage of favorable responses was 69.89%, lower than for the pre-period, when the percentage was 89.37% (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Analysis of the data regarding the degree to which patients' rights were respected

Also, there was an increase in the post-pandemic period in the responses of patients who stated that their rights were partially respected, compared to the 2016-2019 period when the average was 4.1%.

Regarding the negative answers, an increase is observed in the 2022-2023 period (average 3.1%), compared to the 2016-2019 period (average 1.62%).

Because of the awareness related to medical treatment was increased during the pandemic, even if now there is a greater emphasis on informed consent of the patients, the general perception has shifted towards a more negative view concerning the medical procedures and treatments applied to admitted patients (z-test p value<0.001).

Similar findings were also recorded in terms of how patients were informed about diagnosis, investigations, and medication (Figure 11), showing that patients consider more often nowadays that they are not sufficiently informed about their condition and the treatments they are undergoing.

Figure 11.

Analysis of the data regarding the medical information provided

These findings are in accordance to similar studies concerning patient’s satisfaction in Romania, pre- and post-pandemic [9, 10].

From the analysis of the data on the answers of the patients regarding the provision of medicines by the hospital, it was found that the favorable answers are on average 81.35% before the pandemic, with an increase to 86.5% in the period 2022-2023 (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Analysis of the data regarding medication sourcing

Regarding the negative responses, there is an improvement in the post-pandemic period, with a percentage of 3.49%, compared to the pre-pandemic period, when the percentage was 11.77% (z-test p value<0.001), which is an objective assessment of state of things concerning material conditions in the hospital.

However, from the analysis carried out, deficiencies were still found regarding the provision of medicines, which must be fully provided by the hospital.

Regarding patients who stated that they would still use the services offered by SCJU Craiova (Figure 13), it can be seen from the data analysis that the percentage before the pandemic was 69.42, and after the pandemic it decreased quite a lot, to the value of 44.02% (z-test p value<0.001).

Figure 13.

Analysis of the data regarding the options for SCJUC readmission

This is a general confirmation of the theory that, after the pandemic, because the general public was more exposed to medical interactions and news provided in the media, as well as the development of the private practice in Romania, the expectations of the patients have increased [11].

Discussion

The analysis of patient satisfaction data from the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital (SCJU Craiova) highlights significant changes in the post-pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period, both in positive and negative aspects.

General Satisfaction Level

Post-pandemic, general satisfaction (very satisfied+partially satisfied) fell from over 90% (2016-2019) to 83% (2022-2023), because, even if “Very satisfied” responses increased post-pandemic, the “partially satisfied” responses decreased even more, the overall outcome being a decrease of the general satisfaction level. This may reflect deficiencies in certain areas of the services. Another Romanian study shares the same results.

A study by Radu et al. on public hospitals in Romania found similar post-pandemic declines in satisfaction, with higher expectations among patients for service quality and facility infrastructure [9], while another Romanian study, that covers more than a decade of hospital surveys of patient satisfaction claims that there is an overall increase in patient satisfaction, mainly due to the switch of financing from the central administration to a local ones, allowing for better tailored funding for the needs of the community [12].

Even on an international level similar declines are reported, for example research in conducted in the UK noted an increase in dissatisfaction related to resource shortages and longer wait times after the pandemic, aligning with the SCJU Craiova pattern [13].

The 2023 survey recorded the lowest levels of satisfaction since the survey began in 1983-only 24% of the public are satisfied with the NHS.

In regard to specific Healthcare Service Quality, in SCJU Craiova we observed that ratings of “very good” increased post-pandemic, but combined positive responses (“very good”+“good”) fell from 93% to 83%. Moreover, we have seen a significant increase in “not good” ratings post-pandemic.

An US Healthcare study states that, post-pandemic, fewer patients rated their hospital care as excellent, with a shift toward “good” ratings due to perceived understaffing and strained healthcare systems [14], and a study conducted on India’s tertiary hospitals noticed a similar drop in combined positive responses for quality, linked to increased patient expectations and scrutiny of medical protocols [15].

Research conducted in a in a regional psychiatric hospital in Romania, which directly links the degree of patient satisfaction as an indicator of the quality of the provided medical services, shows a decrease of the satisfaction level during and after the COVID pandemic [16].

A study conducted in Ethiopia brings an interesting insight into this matter, showing that patients with no prior history of admission were about 87% less likely to be satisfied than those who used to have previous history of admission.

Interaction with Hospital Staff

While we noticed an increase of "very good" qualification for the medical staff, we also noticed an increase in unsatisfactory ratings and, most important, a drastic decrease on satisfactory or “good” ratings, which demonstrates that, even if some interactions became better, other worsened, which may show either an increase in patient demands or an adaptation of expectations to the new conditions, or even a more negative perception of some aspects of interaction, due to stress from both patients and medical staff.

Overall, the data in our study shows a higher rating for doctors and nurses post-pandemic, but lower for non-medical staff, with greater increases in ratings for doctors compared to nurses, a statement that is in accordance to various other studies analyzed in a systematic literature review [18].

A comparable study in Indonesia found improved post-pandemic ratings for medical staff but noted dissatisfaction with administrative staff interaction [19].

A study based in Saudi Arabia, aimed at nurses’ role in patient satisfaction shows similar patterns in staff friendliness scores, especially for doctors, further enhancing our study’s findings [20].

We have to draw the attention that, for both doctors and nurses, burnout was also associated with up to threefold decreases in patient satisfaction [21, 22].

Hotel Conditions and Cleanliness

Similarly, to the general satisfaction, in spite of the objective increase on the conditions offered by medical facilities and the tighter hygiene measures that remained in place after the pandemic, hotel conditions improved slightly in “very good” ratings, but fell in combined satisfaction scores (good + very good), while cleanliness ratings mirrored these trends, showing an increase in patients’ expectations.

A study conducted in Indian hospitals reflected SCJU Craiova trends, with increased complaints about cleanliness despite enhanced hygiene measures during the pandemic and afterwards [23], while UK NHS post-pandemic studies reported marginal improvements in cleanliness ratings due to heightened hygiene protocols, though accommodation ratings suffered due to overcrowding [24].

Even if hotel conditions and cleanliness are still hot topics in developing countries [25], a new trend is surging, with the apparition of the so-called “medical hotels”, where ambulatory patients that undergo medical procedures can be lodged [26], speculating on the general dissatisfaction of patients with the conditions they find especially in public funded hospitals.

Food Quality

In Craiova we recorded significant declines in food quality ratings post-pandemic, where combined positive ratings dropped from 83% to 64%. These could be due to an increase in patients’ expectations, but it also could reflect a local problem, because in later years, even before the pandemic, there were problems in maintaining a log-term contract with the companies providing catering service for the hospital, due to the small amount of money allocated for meals (there is a national limitation of food expenses in hospitals to a certain amount in lei/day/patient, amount from which it is difficult to create a balanced diet corresponding to the special needs of patients) the price increases due to world-wide and national inflation and the subsequent degrading commercial relations between the hospitals and the food-providers.

However, this isn’t an isolated case in Romania, other research papers signaling similar problems. Studies in other Romanian hospitals found food quality to be a significant dissatisfaction driver in the post-pandemic era, similar to SCJU Craiova findings [9, 12].

Even at an international level, this seems to be a case, for example a study in Canada describes a similar decline in satisfaction with hospital food quality attributed to cost-cutting and supply chain issues exacerbated by the pandemic [27].

Respecting Patients' Rights and Patient Information

Because of a greater exposure to healthcare-related information during the pandemic, more patients felt their rights were only partially respected in the post-pandemic period.

Because of this, it comes as no surprise that favorable responses to this issue fell from 89.37% pre-pandemic to 69.89% post-pandemic.

Studies in Poland noted similar declines in perceptions of respect for patient rights, reflecting heightened patient awareness and expectation [28], and a Turkish post-pandemic analysis revealed concerns about patient rights adherence, especially in resource-constrained settings as an Emergency Department [29, 30].

A Saudi Arabia study emphasizes the impact on patient satisfaction of the information provided by nurses, as they are the medical staff category with the greatest amount of time spent with patients, noticing that nurse’s clearness and completeness when informing about the medical procedures was regarded as very important.

Medication Availability

Objectively, medication provision has improved in the last years in Romania, and especially post-pandemic, although there are still shortcomings. This is why it came as no surprise that we noticed an improvement in favorable responses about medication availability (81.35% pre-pandemic to 86.5% post-pandemic).

Similarly, a study in Vietnam indicates improved medication sourcing due to post-pandemic reforms [31], while a Pakistani experience, compared to other developing countries, shows that contrasting patterns are seen, with medication shortages being a persistent issue in post-pandemic healthcare [32].

Willingness to Return to the Hospital

In Craiova the overall “patient loyalty” decreased. The percentage of patients willing to return dropped significantly from 69.42% pre-pandemic to 44.02% post-pandemic. This is partially due to the increase in patient demands, over time, and markedly after the pandemic, and partially because of the increase on private health-care facilities, mostly for secondary healthcare, but tertiary too, in Romania, with a developing market eager to attract the patients that traditionally accessed public healthcare services.

Declining return rates in Bucharest hospitals mirror SCJU Craiova trends, reflecting increasing reliance on private healthcare [9], and even international studies confirm this, showing a decrease in the willingness to return to public facilities, due to dissatisfaction with overcrowded hospitals and perceived service declines.[33].

These comparisons demonstrate that while SCJU Craiova’s findings align with global and regional trends, there are specific factors like modernization efforts and local demographics that modulate the overall patients’ experience.

Regarding the increase in satisfaction after the pandemic, the percentage of patients who declared themselves very satisfied increased from an average of 25.52% before the pandemic to 38.61%. This suggests an improvement in services or a more effective adaptation to the new post-pandemic conditions.

Conclusion

Although overall patient satisfaction has largely increased, there is a slight increase in dissatisfaction, suggesting that there are areas for improvement.

Thus, although the friendliness of the staff is mostly appreciated, there is a tendency towards polarization, with more very satisfied patients, but also an increasing number of dissatisfied patients.

Patient satisfaction with hotel conditions deteriorated after the pandemic, with a significant decrease in positive reviews.

After the pandemic, the degree to which patients' rights were respected and medical information received are aspects where patients' perception has worsened, requiring significant improvements.

In the 2022-2023 period, we noticed a significant decrease in readmission intention, which indicates a serious problem related to the general perception of the quality of services provided by the public, state hospital.

The recommendations made by the patients were to improve the quality of the food, to equip the rooms with the appropriate medical and non-medical equipment, a more flexible schedule of visits for relatives and to improve the communication between the patient and the medical team, to diversify the existing medication and to ensure sufficient quantities in the hospital pharmacy.

As a final conclusion, although some aspects have seen post-pandemic improvements, such as the staff’s behavior and the provision of medicines, there are important aspects that require significant improvement, such as hotel conditions, food quality and the degree to which patients' rights were respected, as perceived by them.

The decrease in patient confidence in readmission is an important signal that the hospital must take measures to increase the quality of the services provided.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Donabedian A. The Quality of care. How can it be assessed. JAM. 1998;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Working. The principles of quality assurance. Qual Assur Health Care. 1989;1(2-3):79–95. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/1.2-3.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilz S, Hülsmann S, Michallik S, Rimbach-Schurig M, Schollmeier M, Sommerhoff B, Weßling A. Quality Manager 2.0 in Hospitals-A Practical Guidance for Executive Managers, Medical Directors, Senior Consultants, Nurse Managers and Practicing Quality Managers. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2013;107(2):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.lnternational Organisation for Standardisation. Quality Management Systems-Requirements (ISO standard no. 9001:2015). 2015, lnternational Organisation for Standardisation. Available from: https://www.iso.org/obp/

- 5.How Can Hospital Performance Be Measured and Monitored? . 2003 Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/363763./

- 6.Manalu NV, Budiarti T. The Patient Satisfaction on Quality of Health Services in Out Patient Department of Bandar Lampung Adventist Hospital. th International Scholars Conference. 2019;7(1):550–563. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joint Commission International . Benchmarking in Health Care . 2 . lL, USA : Oakbrook Terrace ; 2012 . pp. 176 – 183 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schilling L, Chase A, Kehrli S, Liu AY, Stiefel M, Brentari R. Kaiser Permanente's performance improvement system, Part 1-From benchmarking to executing on strategic priorities. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(11):484–498. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radu F, Radu V, Turkeș MC, Ivan OR, Tăbîrcă AI. A research of service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction-Case study of public hospitals in Romania. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(2):1018–1048. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosma SA, Bota M, Fleșeriu C, Morgovan C, Văleanu M, Cosma D. Measuring Patients’ Perception and Satisfaction with the Romanian Healthcare System. Sustainability. 2020;12(4):1612–1627. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin-Pantelescu A, Hint M. Romanian customers’ satisfactions regarding private health services. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Business Excellence. 2020;14:788–796. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulău D, Craiut L, Tit DM, Buhas C, Tarce AG, Uivarosan D. Effects of Hospital Decentralization Processes on Patients’ Satisfaction: Evidence from Two Public Romanian Hospitals across Two Decades. Sustainability. 2022;14(8):4818–4818. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Care Quality Comission-Adult inpatient survey . 2023 Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/adult-inpatient-survey.

- 14.Goodrich GW, Lazenby JM. Elements of patient satisfaction: An integrative review. Nurs Open. 2023;10(3):1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sultan N, Mahajan R, Kumari R, Langer B, Gupta RK, Mir MT, Chowdhary N, Sultan A. Patient satisfaction with hospital services in COVID-19 era: A cross-sectional study from outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in Jammu, UT of J&K, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(10):6380–6384. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_704_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Băcilă C, Ștef L, Bucuță M, Anghel CE, Neamțu B, Boicean A, Mohor C, Ștețiu AA, Roman M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Management of Mental Health Services for Hospitalized Patients in Sibiu County-Central Region, Romania. Healthcare. 2023;11(9):1291–1291. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11091291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abebe D, Mesfin S, Kenea LA, Alemayehu Y, Andarge K, Aleme T. Patient satisfaction and associated factors in Addis Ababa's public referral hospitals: insights from 2023. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024;11:1456566–1456566. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1456566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira DC, Vieira I, Pedro MI, Caldas P, Varela M. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare. 2023;11(5):639–639. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11050639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moslehpour M, Shalehah A, Rahman FF, Lin K-H. The effect of physician communication on inpatient satisfaction. Healthcare. 2022;10:463–3390. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10030463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhussin EM, Mohamed SA, Hassan AA, Al-Qudimat AR, Doaib AM, Al-Jonidy RM, Al-Harbi LI, Alhawsawy ED. Patients’ satisfaction with the quality of nursing care: A cross-section study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2024;20:100690–100690. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, Geraghty K, Riley R, Zhou A, Panagopoulou E, Chew-Graham CA, Peters D, Esmail A, Panagioti M. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442–e070442. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li LZ, Yang P, Singer SJ, Pfeffer J, Mathur MB, Shanafelt T. Nurse Burnout and Patient Safety, Satisfaction, and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e2443059–e2443059. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandhu A, Sarkar S, Karmakar S, Singh OP. Level of Satisfaction Towards Healthcare Services in Patients Attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital in Eastern India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2023;45(6):591–597. doi: 10.1177/02537176231163580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2023 . 2023 Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/reports/public-satisfaction-nhs-social-care-2023.

- 25.Saini NK, Singh S, Parasuraman G, Rajoura O. Comparative assessment of satisfaction among outpatient department patients visiting secondary and tertiary level government hospitals of a district in Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38(2):114–117. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.112449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaulagain S, Farboudi-Jahromi M, ua N, Wang Y. Understanding the determinants of intention to stay at medical hotels: A customer value perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2023;112:103464–103464. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trinca V, Duizer L, Keller H. Putting quality food on the tray: Factors associated with patients' perceptions of the hospital food experience. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35(1):81–93. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient satisfaction of a health care facility (hospital) in terms of management and in light of meeting the patients' charter of rights. 2024 Available from: https://www.humanizacjamedycyny.pl/en/3430/patient-satisfaction-patient-care-hospital-management-and-in-sight-of-fulfillment-of-patient-rights-charter-2.

- 29.Kaplan A, Kaçmaz HY, Öztürk S. An Evaluation on the Attitude Toward Using Patient Rights and Satisfaction Levels in Emergency Department Patients. J Emerg Nurs. 2024;50(2):243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2023.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alharbi HF, Alzahrani NS, Almarwani AM, Asiri SA, Alhowaymel FM. Patients' satisfaction with nursing care quality and associated factors: A cross-section study. Nurs Open. 2023;10(5):3253–3262. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen B. Q., Nguyen C.T.T. An assessment of outpatient satisfaction with hospital pharmacy quality and influential factors in the context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2022;10:1945–1945. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10101945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atif M. Sehar A., Malik I, Mushtaq I, Ahmad N, Babar Z. What impact does medicines shortages have on patients? A qualitative study exploring patients’ experience and views of healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:827–827. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06812-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan T, Chen X, Li J, Zhang Y. Factors influencing patient experience in hospital wards: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):527–527. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-02054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]